Accreditation, certification, and credentialing are all important levers of change in improving the training of the health care workforce. As explained during the panel on this topic by Alison Whelan, chief medical education officer at the Association of American Medical Colleges, accreditation is the process by which an education program is periodically assessed to determine that it meets an established set of standards considered critical for a quality program. Certification is the process of obtaining, verifying, and assessing the qualifications of a practitioner. Credentialing is the process whereby a specific scope and content of patient care services are authorized for a practitioner by a health care organization. Changes in all three may, over time, have an influence on the numbers and backgrounds of the individuals who deliver behavioral health care to children and families. Challenges include different practices and policies across jurisdictions, a tendency for activities to be siloed, and uncertain sources of funding to make changes.

AN OVERVIEW OF PHYSICIAN TRAINING, LICENSURE, AND CERTIFICATION

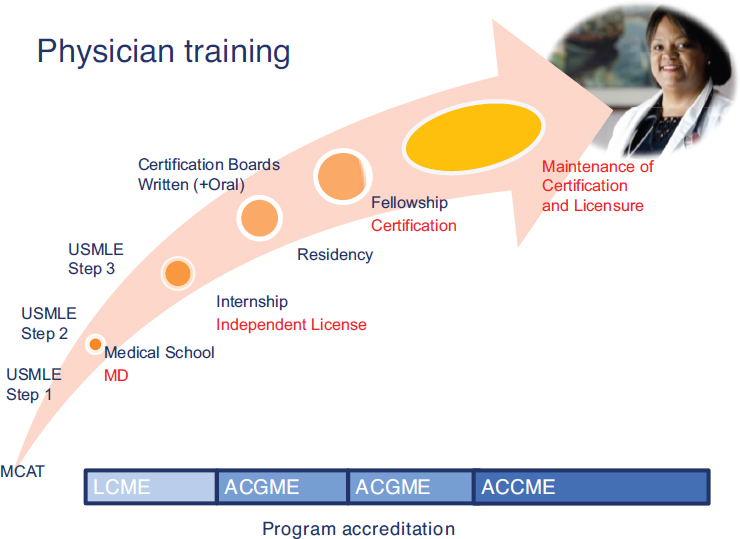

Physician training, licensure, and certification provide a useful overview of the accreditation, certification, and credentialing process, Whelan continued. After, typically, 4 years of medical school and another year of internship, physicians are able to obtain a state-based independent license (see Figure 5-1). Most go on to complete residencies, after which they may be certified by the relevant specialty board (e.g., certified in pediatrics by the American Board of Pediatrics). They may then do a fellowship and achieve additional subspecialty certification, representing, altogether, 8 to 12 years of training.

To receive any state medical license, physicians must pass four examinations that make up the U.S. Medical Licensing Examinations (USMLE). Additional examinations for specialty (residency) and subspecialty (fellowship) certification, and subsequently for maintenance of certification, are required. Accreditation of medical schools is the responsibility of the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME), while the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) are responsible for graduate medical education and continuing medical education, respectively.

One important trend in medical education, and increasingly in certification, is the move toward competency-based assessment, Whelan explained. Core competencies defined by the ACGME and fairly widely adapted across the continuum of medical education with some variations include the following:

- medical knowledge,

- patient care,

- interpersonal and communication skills,

- professionalism,

- system-based practice, and

- personal learning and improvement.

Competencies are based on the idea that physicians start as novices and progress through the stages of advanced beginner, competency (needed to be an independent practitioner), proficiency, and expert (required to be a consultant, teacher, or leader). Given this context, improving behavioral health outcomes for children, youth, and families requires considering the critical competency gaps at each level of physician training, Whelan observed. For example, large gaps that she cited are cultural competency, an understanding of unconscious bias, and interprofessional education, all

NOTES: ACCME = Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education, ACGME = Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, LCME = Liaison Committee on Medical Education, MCAT = Medical College Admission Test, USMLE = United States Medical Licensing Examination.

SOURCE: Whelan (2016).

of which have been added to LCME accreditation and to medical student exams.

In considering the impact of changes at various levels of physician training, changes at the medical-school level would reach the largest target group but would necessarily be more general. To reach more specialized skills or higher expertise in an area, the focus could be on certification at the pediatric specialty training and the subspecialty training level. At this specialized level, identifying the critical competency gaps and the physician groups in which those problems should be addressed is critical, Whelan said. An area that has been largely neglected but offers a tremendous opportunity to address gaps in current practice is continuing medical education, she added.

Whelan also urged consideration of the tools people use to learn. “If you make great teaching tools available, people will use them. If you just shake your finger at them and say ‘do it,’ but you don’t give them the tools, then people just get frustrated,” she commented.

CERTIFICATION OF PEDIATRIC NURSES

The certification of pediatric nurses is another good example of how oversight processes can improve the health care workforce. The Pediatric Nursing Certification Board (PNCB) is the largest certification board for pediatric nursing in the United States, explained Adele Foerster, the organization’s chief credentialing officer. Its exams are recognized and endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics, Association of Faculties of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners, National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners, Society of Pediatric Nurses, and all state boards of nursing. More than 42,000 people actively hold at least one PNCB certification, and the organization certifies more than 95 percent of pediatric nurse practitioners in the country.

In 2011, PNCB launched a specialty exam for advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) to validate their knowledge and competencies in providing care related to common pediatric developmental, behavioral, and mental health conditions. In addition, behavioral and psychological concerns have ranked fourth or fifth on the pediatric nurse practitioner exam, which tests pediatric nurse practitioners on essential job tasks related to common primary care, since 2008.

Entry-level certification for either pediatric or family nurse practitioners is always preceded by graduation from a master’s or doctoral-level academic program, including clinical preceptorships. Added specialty certification for pediatric mental health specialists is based on knowledge gained through on-the-job experiences, continuing education, collaboration and preceptorship, and online courses.

The certification process is driven by research, Foerster explained. An initial role delineation study is followed by job task analyses every 3 to 5 years. Tasks essential to practice must meet criteria to be on the exam content outline, with standard-setting to establish a passing point. The exams are secure and criterion referenced, with each scored exam question backed by valid statistics. Certification is followed by recertification, annually for primary care nurse practitioners and every 3 years for pediatric mental health specialists.

An analysis of nurse practitioners who provide behavioral health care found that they average 11.5 years of experience, spend 80 percent of their work time seeing patients with behavioral health conditions, and provide behavioral health services from 10 to 40 or more hours per week. The majority (55%) are in primary care settings, with 24 percent in specialty clinics or specialty practices and 11.5 percent in psychiatric settings. Only 71 percent can prescribe Schedule II medications, which is an issue given state-to-state variability in this measure. For example, a nurse practitioner can work in developmental behavioral health for 20 years in one state and then move to another state and lose the ability to prescribe Ritalin for common ADHD. “That kind of thing is a barrier,” said Foerster. Billing codes are typically at a complexity level of three or four, and many are time-based codes.

When asked about the sources of their education in pediatric developmental, behavioral, and mental health since graduation from an APRN program, substantial majorities cited in-person workshops or training (82.9%), on-the-job training (80.5%), and online continuing education courses (75.4%). Smaller percentages said they were self-taught (54.3%) or had taken academic courses (46.1%). The numbers were similar, though slightly smaller, for psychopharmacology education.

Foerster closed by recounting the experiences of a pediatric nurse practitioner in primary care who also holds the pediatric primary care mental health specialist credential and works in a hospital outpatient clinic. Children in the clinic with depression, anxiety, panic disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, disordered eating, and other conditions were often falling through the cracks and not getting the care that they needed. As part of her doctoral project, this nurse practitioner challenged the existing patterns of outsourcing behavioral health care and implemented a model that has “transformed her outpatient practice,” said Foerster. “She has developed faster access to care for patients. She has reassured families that they are going to get started on care right away. . . . She benefits not only the patient but the practice as well, because [patients] are kept in the health care home and are financially stable.”

CERTIFICATION AND MAINTENANCE OF CERTIFICATION

Moving to a specific example of certification procedures for physicians, Julia McMillan, emerita professor in the Department of Pediatrics at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, described how the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) has been leveraging its influence to ensure that pediatricians are appropriately trained in behavioral health care. According to its mission statement, the ABP certifies general pediatricians and pediatric sub-specialists and provides assurance to the public that a general pediatrician or pediatric subspecialist has successfully completed an accredited training program and has fulfilled the continuous evaluation requirements. The ABP also undertakes new initiatives that not only continually improve the standards of its certification, but also advance the science, education, study, and practice of pediatrics. Requirements for initial certification include sitting for a certifying examination after completion of an accredited pediatric residency program, and receiving an attestation from the program director that an individual has achieved appropriate competence and qualification for a license to practice medicine in a state.

The Pediatric Review Committee (PRC) of ACGME accredits residency programs based on the structure of the program, the curriculum of the program, the patient care experiences that residents have when they are engaged in the program, the qualifications and number of the faculty members, working conditions, and the outcomes of training based on faculty evaluations and APB exam pass rates. With regard to behavioral health care, the PRC has what McMillan called minimal requirements. Each residency program must have at least one faculty member who is an expert in developmental and behavioral pediatrics, and each resident must spend a month or 200 hours in developmental and behavioral pediatrics with an appropriate curriculum, goals, and objectives. One month out of almost 3 years may not seem like much, she acknowledged, but residents also receive some training in behavioral health outside that specified month.

The PRC has developed milestones of observable behaviors that trainees are expected to exhibit as they progress during their 3 years of training. For example, trainees are expected to develop the ability to “communicate effectively with patients, families, and the public, as appropriate, across a broad range of socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds.” The competency encompasses the following milestones:

- Novice: Relies on template to prompt interview questions

- Level 2: Uses interview to establish rapport

- Level 3: Uses verbal and nonverbal skills to promote trust, respect, and understanding

- Level 4: Uses skills to establish therapeutic alliance; tailors communication to the individual

- Expert: Fosters a trusting and loyal relationship; intuitively handles the gamut of difficult communication scenarios with grace and humility

Trainees would not be expected to become experts during their residency training, McMillan noted, but would do so as their skills continue to mature as pediatricians.

The system of milestones has both advantages and disadvantages, she said. It facilitates assessment and feedback. It also provides for national standard setting, in that every residency program now has to report to the ACGME on each resident’s pattern of acquisition of skills as they go through training.

The disadvantage is that the situation in which a trainee’s communication skill is being assessed is not considered, she noted. For example, the milestone does not specify whether residents were able to communicate with patients whom they already had seen many times before or with new patients who are in a chaotic emergency department.

To overcome this disadvantage, the ABP and other medical boards have been developing Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs), which are agreed-upon lists of activities within a given specialty or subspecialty that a physician would be expected to be able to perform competently and without supervision, with the milestone assessed within that context. For example, EPA 9 (of 17 EPAs) for general pediatricians is assessment and management of patients with common behavioral health problems. Examples of activities, McMillan noted, are, “Can you apply that communication skill in the setting of a child with a behavioral problem? Can you develop a rapport with the family? Can you take a communication in that setting and apply it?”

According to a 2013 survey by the American Academy of Pediatrics, 65 percent of the 512 pediatricians who were surveyed indicated that they lacked training in the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with behavioral health problems. Forty percent said that they lacked confidence in recognizing behavioral health problems; more than 50 percent said that they lacked confidence in treating behavioral health problems; and 44 percent said that they were not interested in treating, managing, or comanaging child behavioral health problems. These numbers distinguish this EPA from most of the other ones in pediatrics, McMillan said, noting, “Pediatric faculty generally haven’t been trained to do this themselves, so they’re not equipped to model this or to teach it or to assess residents in behavioral health care. That’s really not true for the other EPAs,” such as caring for a newborn.

Challenges for pediatric residency program directors, for the ABP, and for the pediatric community as a whole are to define the scope of care expected of pediatric residency graduates, create curricular models that result in the necessary skill development, provide experiences and environments in which pediatric residents can develop skill and knowledge, provide faculty mentors who will teach and model effective care, and develop assessment tools to determine when residents have achieved these goals.

McMillan also briefly touched on maintenance of certification. Since 1988, certificates issued by the ABP have been time-limited. Pediatricians have to maintain certification through participation in programs to verify commitment to professionalism, lifelong learning, self-evaluation, cognitive expertise, and improvement in practice. The board has begun working on maintaining certification in behavioral health, and it is seeking to identify ways for those already in practice to improve their knowledge, skills, and practice.

CURRICULAR CHANGE DRIVEN BY ACCREDITATION

Jeffrey Hunt, professor in the Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at the Alpert Medical School of Brown University, briefly talked about how curricular change can be driven by ACGME. Responding to several sources of pressure to define and assess physician competencies and outcomes, milestones were developed to move away from idiosyncratic training experiences toward more deliberate practice. Under the current system, ratings for each resident in all programs across the United States are generated and sent every 6 months to ACGME. For example, in child psychiatry, 22 subcompetencies have been specified, with developmental progressions and milestones at five levels. An example, from level four in the subcompetency of “Psychiatric Formulation and Differential Diagnosis” is “Incorporate subtle, unusual, or conflicting findings into alternative hypotheses and formulations.”

This exercise has allowed gaps in curricula and assessments to be identified. For example, child psychiatry “had never spent much time thinking about wellness or prevention,” said Hunt, but now these topics are incorporated into the milestones. Similarly, the milestones include content on neuroscience and genetics, although Hunt acknowledged that many of the 121 child psychiatry programs in the United States do not have faculty who can teach these subjects.

Definition of the milestones also has increased collaboration and greater sharing of existing curriculum and other resources among groups. For example, the National Neuroscience Curriculum Initiative (http://www.nncionline.org [September 2017]) has produced a portable, online, and free educational module that gives faculty members the opportunity to learn how to teach neuroscience and genetics.

ACCREDITATION AND THE TRAINING OF CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGISTS

Several activities at the University of Delaware related to the training of clinical psychologists provide insights into how to influence the behavioral health care workforce, said Ryan Beveridge, director of the Center for Training, Evaluation and Community Collaboration and associate professor of psychological and brain sciences at the university. The Delaware Project, for example, began with a group of clinical psychology faculty members who were concerned about the science-to-service gap, “where what we know works in the laboratory isn’t necessarily working in the community.” The gap exists for a variety of reasons, Beveridge noted, but clinical psychology faculty are interested in addressing it from the perspective of graduate student training. In particular, the Delaware Project sought to break down the silos that separated laboratory intervention research from community research and clinical efforts by training future psychologists to integrate their research with the real world of the workforce. “We wanted students to have more experience in translating their laboratory work into the community, but also be thinking about how their community experiences, both clinically and with research, would feed back into their laboratory work so we might develop more relevant, potent, feasible interventions,” Beveridge said.

In a related initiative, the university’s Center for Training, Evaluation, and Community Collaboration (C-TECC) is reshaping the way treatment developers, community partners, graduate students, and clinical trainers collaborate to make clinical science more impactful.

C-TECC functions not only as a training clinic, but also as a connection between the university clinical science program and the broader academic and behavioral health community. Students are trained to be experts in evidence-based practices, as well as trainers and consultants to community providers. C-TECC is a hub that allows students to work with the community to identify needs; plan actions; and implement, evaluate, and refine treatments. By connecting clinical science training directly to the community, each partner can inform and refine the activities of the other.

Finally, Beveridge discussed the new Psychological Clinical Science Accreditation System (PCSAS), launched in 2007 partly to address the need for clinical science training programs to adapt to the changing workforce demands for Ph.D.-level clinical psychologists. It emphasizes the role of sound clinical psychological science as a basis for all research and clinical training, but gives programs great flexibility in training foci and methods. PCSAS emphasizes program graduates’ career placements as an important indicator of the quality of the training program. It was recognized as a national accreditor by the Council for Higher Education Accreditation in

2012. Since then, it has accredited approximately 30 top Ph.D. programs in North America, with the number continuing to increase.

To be accredited by PCSAS, a program must provide all of its graduates with first-class, science-centered application training, including their practicum and internship training, said Beveridge. In this way, it prepares graduates for licensure to serve as independent providers of psychological services; to act as supervisors and trainers of other providers; and to integrate their scientific knowledge and apply their training in such roles as treatment developers, evaluators, educators, and trainers.

Training opportunities like those offered at C-TECC and inspired by the Delaware Project take a lot of time, Beveridge noted. PCSAS is not prescriptive in its training requirements. It pays attention to things like organization of program content and coherence. The system also tries to foster diverse training models as long as program graduates function as clinical scientists who are grounded in scientific epistemology and evidence-based practice and are competent to assume independent responsibility for patient care.

TRAINING AND CREDENTIALING FAMILY PEER ADVOCATES

Formed in 1995 by a dedicated group of parents and family peer advocates, Families Together in New York State, Inc. (FTNYS) is a family-run, not-for-profit organization, explained Susan Burger, director of family peer advocate credentialing and workforce development. Its mission is to provide a unified voice for families raising children with social, emotional, behavioral, and cross-systems challenges. FTNYS promotes the principles of family-driven care, including partnership and advocacy on all levels. It also supports YouthPower!, a statewide youth-run organization. FTNYS has approximately 1,000 members and close to 3,000 e-mail subscribers. It manages New York State’s Family Peer Advocate (FPA) training and credentialing programs.

Over the past decade, an effort has developed within New York State and throughout the country to formalize the work of family peer advocates and develop family peer support services into a recognized profession, explained Burger. An important step in this process in New York State was the development of a consensus definition for family peer support services, with activities falling into eight broad categories: outreach and information, engagement, bridging and transition support, advocacy, self-efficacy and empowerment, community connections and natural support, parent skill development, and promoting effective family-driven care.

Family peer advocates are different than other workers who support families, said Burger. They are parents and/or primary caregivers who have navigated systems on behalf of their children. They have firsthand experi-

ence raising a child or children with difficult and serious challenges. Family peer advocates help parents take the time they need to question, learn, and try new skills. “Experience and research have shown that when parents engage with the system and become more active partners with providers, there are better outcomes for the child,” she said.

Until recently, formal data on the impact of family peer support have been mostly anecdotal, although Burger said that “I know, for myself, it made a big difference in how I was able to partner with providers and how I was able to care for my child.” Data are currently being collected in New York State and throughout the country using such tools as the Family Assessment of Needs and Strengths and the Child and Adult Integrated Reporting System.

With support from the Office of Mental Health in New York State, a formal FPA credentialing process was started in 2011. Requirements include proof of age, proof of education, 1,000 hours of work as a family peer advocate, proof of lived experience, completion of the Parent Empowerment Program (PEP) training, three letters of recommendation, and an agreement to practice according to an established code of ethics.

A new provisional credential gives advocates the opportunity to get credentialed before getting a job. It also gives employers the opportunity to hire trained and credentialed workers who can bill for their work from their first day on the job. The provisional credential is valid for 18 months, and during that time the expectation is that the family peer advocate will go on to meet the requirements for the professional-level credential.

PEP, which is the required training for all credentialed family peer advocates, was developed in 2005 to meet the growing workforce demands. Designed specifically for individuals doing family peer support work, it was developed by clinical partners, family peer advocates, and researchers and is delivered by a team of family peer advocates and a clinical partner. Based on core competencies derived from statewide input, the PEP training has had to evolve to meet the needs of the changing health care environment, Burger said. An updated training is currently in development that includes online modules, a 2-day in-person component, and 12 one-hour consultation calls.

As a lever of change, family peer advocates have had a positive impact on both the systems that serve families and the field of family support itself, said Burger. The approach, she said, has “started to change the way the health care system and the social services system think about family peer support and the family peer support services workforce. Having a credential has added legitimacy, respect, and a clearly defined role to what started 25 years ago as a grassroots, whatever-it-takes service.” The credential also has helped pave the way for family peer advocates and family peer support services to integrate into a variety of new settings, including hospitals, clinics, and child welfare and juvenile justice settings.

Finally, Burger noted that research on quality indicators is further informing the training and program evaluation and that the development of quality indicators has led to a discussion about how and where family peer support can have the most impact.

ACCREDITATION OF PATIENT-CENTERED MEDICAL HOMES

The patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model is based on a framework of being coordinated, accessible, committed to quality and safety, comprehensive, and person centered. But the general model can be implemented in many different ways, depending on the marketplace, the consumers served, the setting, and other factors, noted Marci Nielsen, president and chief executive officer of the Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative (PCPCC).

PCPCC, which was founded in 2006 by four primary care physician organizations, serves as an advocate of high-performing, high-value primary care. “You cannot do that in a primary care practice all by itself,” said Nielsen. “You must partner with the rest of the medical neighborhood.” In particular, behavioral health clinicians are strong advocates of integrating behavioral health services into primary care when appropriate, she said.

The accreditation of PCMHs raises some fundamental questions, Nielsen noted. Is accreditation a quality improvement process for practices? Is it a payment model for government and/or commercial plans? Is it a recognition or certification process for payers and purchasers? Or is it a “Good Housekeeping” seal of approval for the public?

Answering these questions involves coming to an agreement on what it means to be accredited, said Nielsen. Accreditation and certification require mastering many granular details, which can risk losing sight of the ultimate objective. Furthermore, when an organization takes on an accreditation role, it becomes the tester. “You aren’t necessarily the enemy, but you aren’t the friend anymore. You aren’t the advocate,” she said.

Nielsen identified four guiding principles to improve PCMH certification: (1) align all certification programs with the attributes and outcomes of the ideal PCMH; (2) identify change concepts most essential to achieving the attributes and outcomes; (3) promote change concepts that result in PCMH attributes and outcomes; and (4) support a pathway for technical assistance for certification. These are valuable principles to guide the creation of person-centered, team-based primary care, she concluded.

DISCUSSION

The discussion session focused largely on maintenance of certification requirements. As Whelan said, continuous professional development and

continuing medical education have “probably been the least developed over time and are the greatest opportunity for growth.” Taking tests for maintenance of certification can be frustrating as the fields and the tests both change, she noted, but more educational research on effective training for practicing physicians could ease these frustrations and improve lifelong learning. For example, she said, “what aspects of maintenance of certification are really effective, because everyone has different scopes of practice. That’s important, and it’s going to take time to sort that out.”

Whelan also pointed out that physicians bear a huge burden of work that is not patient-centered. “Until that gets better, the ability to be compassionate and not burned out with your patients is limited, let alone becoming excited about learning something new,” she said. “Physicians themselves need care.” Whether the issue is improving quality or adopting new ways of teaching, she added, “if you don’t make it possible for those physicians to do that, we’re failing everybody.”

Nielsen likewise pointed to the pressures on physicians and the push-back that is resulting. “They feel inundated with questions about proving their professionalism,” she said. One promising approach, she suggested, would be to take advantage of the interoperability of behavioral health records to provide an input into the maintenance of the certification process so that physicians do not need to spend as much time away from their patients and families.

McMillan pointed to the importance of continuing education for remaining up to date in a field. Physicians “have to continue to learn in ways that reflect the changing needs of society,” she said. For example, pediatricians need to learn how to provide better behavioral health care, collaborate, and improve their practice environments.

This page intentionally left blank.