While digital technology can improve health outcomes, particularly in low-resource settings, a fragmented landscape of actors and interests working to implement digital health solutions can lead to a lack of coordination, waste, and unrealized benefits. There can be an opportunity to build health solutions around market needs in a coordinated and integrated way if digital health strategies are aligned with the health priorities established by countries and communities. Starting with country- and community-led priorities can aid the private sector in developing digital health strategies that are responsive to the needs of patients and communities. Collaboration among the actors of the ecosystems for health and technology advances the opportunities for business and therefore impact.

This workshop’s third session featured lessons learned from strategies based on country-level priorities, explored frequent barriers and challenges, and distilled critical success factors. The session began with a context-setting presentation by Neal Myrick from Tableau describing an organic partnership that developed to eliminate malaria in Zambia. Next, each of the other three panelists—Lesley-Anne Long from PATH,1 Olasupo Oyedepo from the Health Strategy and Delivery Foundation’s ICT4HEALTH project in Nigeria, and Alvin Marcelo of the Asia eHealth Information Network (AeHIN)—gave short presentations on the projects in which they are involved that aim to improve digital health coordination to meet country and community needs. Elaine Gibbons from PATH then moderated an open discussion with the panelists and workshop participants.

ENGAGING DIGITAL “TEENAGE” COMPANIES IN GLOBAL HEALTH

Tableau, explained Neal Myrick, is a partner in a project that PATH has organized to outfit more than 1,200 community health workers in southern Zambia with mobile technology they can use to record data on the incidence of malaria and track the progress being made in Zambia’s

___________________

1 Lesley-Anne Long from Digital Square (hosted at PATH) as of September 2017.

efforts to reduce the number of malaria cases in the country. Using conventional malaria control methods, the Zambian Ministry of Health, PATH, and other partners had achieved a marked reduction in malaria cases in southern Zambia, but getting to zero cases was proving to be a large challenge, in large part because 80 percent of individuals infected with the malaria parasite are asymptomatic. “When somebody does get sick, health officials see that person as a canary in a coal mine. If that person is sick, then in all likelihood there are a bunch of people back in the village who are carrying the parasite and do not even know it,” said Myrick.

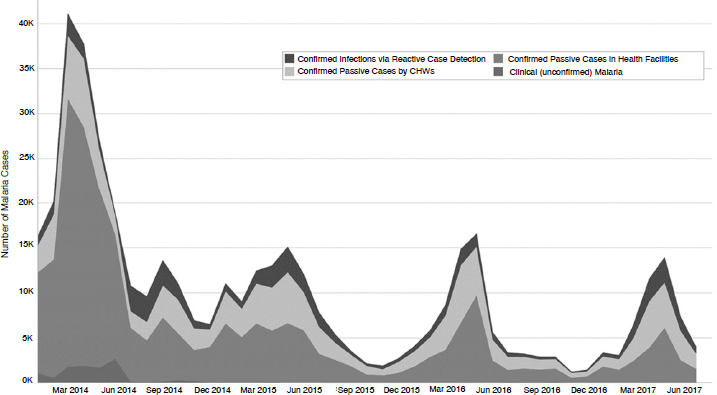

Today, when someone in Zambia’s Southern Province is diagnosed with malaria, community health workers go to the individual’s village and administer a test for the parasite to everyone in the village. They then treat everyone who tests positive for the parasite, even those who are asymptomatic, and help the villagers implement bed nets, one of the most effective methods for preventing mosquito-to-human transmission of the malaria parasite. Taking this approach and repeating it in neighboring villages, the goal is to create malaria-free zones and to use the data the community health workers collect to help decision makers at all levels best direct resources. Myrick noted this approach has cut the number of malaria cases in the Southern Province and the number of malaria deaths significantly over several rainy seasons (see Figure 4-1).

The notion of using data to fight infectious disease is starting to spread and take root in other countries, including Vietnam, where Tableau is partnering with PATH, the Vietnam Ministry of Health, and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to implement an emergency operations center for disease surveillance. Tableau’s role, he explained, has been to provide software and training that enable the government to collect data remotely, have it transmitted into a central system, and then push an analysis based on those data back to the field in the form of interactive visualizations. Those visualizations show when and where infectious diseases are being diagnosed and help the Ministry of Health predict where infectious diseases, such as Zika, malaria, and yellow fever, are going to be diagnosed so it can mobilize resources early and prevent an outbreak from becoming a pandemic. Myrick and his colleagues at Tableau are excited about using public–private partnerships (PPPs) and various philanthropic, corporate, and government funding mechanisms to spread the models they have applied in Vietnam and Zambia to other countries.

Recounting the story of how these partnerships with PATH came about, Myrick said that when PATH first approached him, he expected to be asked for money or use of the company’s business intelligence software. Instead, the PATH representative asked him if he would like to help eliminate malaria in Zambia. What PATH wanted was actual engagement

NOTE: CHW = clinical health worker.

SOURCES: As presented by Neal Myrick on May 11, 2017. Figure developed by PATH for the Visualize No Malaria campaign, a partnership between PATH and the Tableau Foundation. Data source: Zambia Ministry of Health.

and partnership to realize this objective. “So we are not engaged just as a donor or a vendor, but as a partner in helping solve problems on the ground,” explained Myrick.

As a fully engaged partner, Myrick learned that there were other technological needs that PATH had identified as essential for facilitating this project. One such need was the ability to translate District Health Information Software data into a format that Tableau could import for analysis. Myrick contacted the Tableau Zen Masters, a collection of some 25 customers and partners who are experts at using Tableau and data in general, and asked if they would be interested in helping eliminate malaria in Zambia. “Absolutely,” was the answer, but the Zen Masters soon realized they needed additional resources for this project, and they contacted other consulting firms to lend their expertise, pro bono, to the project.

Eventually, as other technological issues arose, Myrick contacted other small companies who have also donated time and software to the project. One by one, technology companies started joining this 5-year campaign, which was launched with the website VisualizeNoMalaria.org. He noted

that one of the messages he gave to the technology partners was that malaria cannot be cured in 1 year, and if they were going to commit to the project, they needed to do so for the full 5-year term to meet the Zambian government’s goal of having the country be malaria-free by 2021.

Myrick pointed out that these “teenage” companies are not the titans of the information technology (IT) industry. Many of them, he explained, operate in cutthroat business environments with many competitors, and they have to put all of their energy toward competing in the marketplace to generate the revenues that enable them to survive. Nonetheless, these companies have become willing partners in this project. The reasons were many, including the fact that the partnerships grew organically, each company was asked to deliver core competencies, and the process of becoming a partner was easy. “There was no paperwork,” said Myrick. “It was not 6 months of negotiation over their engagement and indemnifications. It was: ‘We need your technology, we need it now, can you do it?’ followed by yes and done.”

Another key to success in the partnership in Zambia was that the Tableau Foundation’s grants are unrestricted, which encourages innovation and flexibility. In addition, PATH’s 10-year working relationship with the Zambian Ministry of Health meant there was on-the-ground expertise in both the local cultures and how the government worked. While the teenage technology companies provided the technology, PATH provided the expertise in how to assemble those technologies in an effective way to meet the needs of the government. “Having an implementer like PATH that can actually pull things together and design the right solution for Zambia is something I think that has led to the success of this project,” said Myrick.

PATH’S DIGITAL HEALTH INITIATIVE2

Lesley-Ann Long shared another technology-enabled initiative that PATH is leading to increase coordination and response in health emergencies. During the 2014–2015 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, more than 50 different technology platforms were developed and deployed to respond to different aspects of the crisis. Most of the organizations developing and deploying these platforms did so without involving the local governments or with much understanding of the context in which the platforms would operate, and as a result, the ministries of health had a hard time understanding what was happening in their countries and which data

___________________

2 Digital Square is a U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) program designed and funded in partnership with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF). PATH announced the program in September 2017 with more than 40 partners.

they could trust, said Long. In addition, once the crisis was over and the organizations that had deployed these platforms departed, there was little expertise remaining regarding how to use these platforms, integrate the data they generated, and use the data to make informed decisions. Long noted that this is not an unusual occurrence for those who work on development projects, which is one reason why so many pilot projects developed during crises fail to persist or scale.

The Digital Health Initiative is a U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) program designed and funded in partnership with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF). The initiative was launched to address the coordination problems in global digital heath projects and to support countries to create national-level, integrated digital health systems. At the time of the workshop, the initiative was beginning conversations about how it can support governments to create digital systems that donors can co-invest in and that technology and global health partners can get behind and support in a coordinated manner.

Long explained that the initiative was created to take on four roles:

- Advocating for national integrated digital health systems and the use of global goods (technologies, often open source, which can be reused, adapted, and scaled);

- Coordinating the activities of the donors and technology community through the Digital Health & Interoperability Working Group and its 100+ members;

- Coordinating smart investments in global goods, so that every dollar invested stretches further; and

- Establishing an African Alliance of Digital Health Networks to build and support the development of the next generation of in-country, technology-savvy leaders who will be able to decide how investments will be made to best meet their countries’ needs.

Long then noted that the initiative’s role includes working with governments, the private sector, and others to promote greater collaboration and coordination around investments in digital health. “Collaboration is hard to do, and it takes a lot of time,” said Long, and “you cannot do it by Skype. You have to go to the country, and you have to meet people and build those relationships.” She added that few donors fund collaboration and convening activities and that with a mandate to do this kind of work, the initiative can act as a neutral broker that can bring the “usual global [development] players” together with technology companies, governments, and the people working locally in these countries to have the conversations needed to create effective partnerships.

IMPLEMENTING A NATIONAL EHEALTH STRATEGY IN NIGERIA

In 2013, the Nigerian Minister of State for Health looked at the national health landscape, and he was convinced that technology could be leveraged to impact health outcomes but was concerned by the abysmally low return on investment given the huge amounts of money being put into technology in the health sector, said Olasupo Oyedepo. Working with the communication technology minister, the Minister of State for Health secured support from the Norwegian Aid Agency through the United Nations Foundation and created a process and project—tagged ICT4Saving One Million Lives—to, among other things, drive the development of a national eHealth strategy. Oyedepo recounted that the strategy development team ran into a number of problems. The first problem, which many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) experience, is that any digital health strategy needs to be designed with the end users in mind, but the intended end users were not appropriately informed about digital health to provide useful input. Thanks to the flexibility of their donor, Oyedepo and his colleagues were able to take 3 months to focus on educating stakeholders about the digital health ecosystem. They also used the World Health Organization (WHO) and International Telecommunication Union national strategy document as a guide and invested time strengthening and building the capacity of the digital health ecosystem.

These efforts paid off, said Oyedepo, because the resulting conversations with potential partners in government, the private sector, international development organizations, and the health sector became more than just listening to presentations and taking notes. “We had individuals in the room who could drive a discussion about how digital [strategies] will really help optimize health,” said Oyedepo. The lesson here, he said, was “strengthen the capacity of the group you are working with and life becomes easier.” Instead of driving the conversation, his team’s major job was to keep people on track, document ideas, and help tease out the substance of those ideas.

The vision of the resulting national health strategy is that by 2020, eHealth will help enable and deliver universal health coverage in Nigeria. Arriving at that vision, he recalled, involved many heated discussions. Some of the stakeholders wanted the focus to be on affordability, others on improving access to care and the quality of care, but in the end, everyone realized that all of these are attributes of universal health coverage.

The purpose of Nigeria’s national digital health strategy was to put in place overarching guidance for the use of technology in health and to then strengthen the capacity of the necessary and appropriate government structures to govern the implementation of proven technologies

throughout the nation. Today, Oyedepo and his colleagues are working to support the government’s efforts to create and strengthen those governance structures, build capacity, strengthen collaborations, and empower the government to be able to ask some fundamental questions before it makes digital health investments that best serve Nigeria’s needs and that can be sustainable when outside funding ends.

One lesson he has learned over the course of these activities has been that when putting together partnerships, whether with donor organizations, governments, or the private sector, it is essential to acknowledge the role, value, and relevance of every partner. For example, there is nothing wrong with a private company wanting to make a profit or with government wanting to improve the lifestyle of its citizens. The key is to find the middle ground that reflects the values important to each partner. Finding that middle ground depends more on the people and organizations involved than the technology, and it requires building trust and a strong sense of collective ownership among the partners.

ASIA EHEALTH INFORMATION NETWORK

AeHIN was born out of a conference in 2011 organized by WHO and USAID on health information systems interoperability, said Alvin Marcelo. At the end of the conference, everyone was in agreement that health information system interoperability did not exist even within Ministries of Health. Three months later, he recounted, WHO hosted another conference, with similar attendees arriving at the same conclusions. He noted that the conferences delved deeply into the problems, but no clear solutions arose. Frustrated with the stagnant state of affairs, Marcelo pulled together a group of colleagues from Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam to work on common solutions to interoperability and to learn from each other’s experiences.

With a small grant from WHO, Marcelo and six colleagues from as many countries created AeHIN and developed a 5-year plan to build the network. The network then received additional support from the Norwegian Agency for Development, USAID, and Canada’s International Development Research Centre to build a platform for developing solutions. After five annual meetings of the network, trusted relationships have developed that enabled members to help each other solve health information systems’ interoperability problems. He added that he appreciates that the development partners, government representatives, and private-sector vendors who attend the annual meetings focused their discussions on how they can assist countries in solving those problems.

Marcelo noted that the organization’s focus has developed to working with countries to address various gaps that impede interoperability. One

common gap is not having a governance mechanism that can guide the activities of the many stakeholders and their competing agendas. “Unless you have a framework, you can lose your way,” he said. As an example he shared how one could get lost amidst the complexity of computerizing 1,600 hospitals in the Philippines, let alone one, without a framework and governance mechanism to guide them. Other important gaps include not having people with the right capacities and skills to build the architecture laid out in the framework and not having standards in place to create an interoperable architecture.

For a governance structure, the network has adopted the COBIT 5 framework developed by the Information Systems Audit and Control Association, and 22 people from network countries have become framework certified. Marcelo said that these individuals now have the confidence that they can manage the complexity involved in creating and managing an interoperable, nationwide eHealth information system. Regarding system architecture training, the network has adopted The Open Group Architecture Forum (TOGAF) certification framework, and there are now 12 certified enterprise architects in Asian ministries of health. He explained that those who passed were health professionals, not technical staff. Later, this group of architects reviewed and adopted the Open Health Information Exchange (OpenHIE) interoperability framework as one with just enough sophistication and complexity for LMICs to understand and implement, said Marcelo.

Currently, the network is working on developing program management skills among network members, and the Malaysian Ministry of Health is offering a training program that includes planning, procurement, program evaluation, and monitoring. The network is also looking at the PRINCE2 (Projects In Controlled Environments) and PMP (Project Management Professional) frameworks for program management. Marcelo noted that once network countries have developed capabilities in governance, architecture, and program management, they will be able to select among the many standards that exist for interoperability.

Marcelo said PPPs can only develop and be successful when government realizes that it has to do its part, which is developing those capabilities. With a governance structure, architecture, and program management capabilities in place, private-sector companies can then come in with their technologies and data and create national health information systems that are interoperable. He noted, though, that governments already have relationships with companies in the private sector that have developed from technology acquisition programs outside of the health sector, and that these relationships can be important when the health ministry starts talking to vendors about purchasing technologies. In fact, the network holds a biweekly webinar during which ministries of health and national

insurance agencies talk about how they were able to solve specific problems working with specific vendors, who when asked, are allowed to discuss the features that enabled a particular solution. “We decided it will be the ministry making the presentation and the private-sector vendor providing support to the ministry,” said Marcelo. “I think that is a good way to model public–private partnerships, where government shows leadership and the private sector shows support.” As a final comment, he said AeHIN is starting to work with countries in Africa and hopes to start a collaboration soon with Oyedepo’s group in Nigeria, which is also certifying people in COBIT 5.

POTENTIAL OPPORTUNITIES TO ACHIEVE SCALE

When asked to comment on how Tableau perceives the business opportunities for applying its products and services to global health, Myrick noted that he runs the company’s social impact team, whose mission is to encourage the use of facts and analytical reasoning to solve the world’s problems. “I am lucky in that I do not have a quota, so I am not responsible for generating revenue or new customers, and I can legitimately go after our mission without the sort of inherent conflicts people perceive,” he explained. He and two colleagues currently work in 54 countries through partnerships with PATH and networks such as AeHIN. The attraction of working with AeHIN, said Myrick, is that he and his team could play their part in building data literacy and capacity, which has allowed Tableau’s work to scale. Similarly, he said, his team works with the corporate office of Feeding America and by doing so has a beneficial effect on the organization’s 200 food banks around the United States. In Zambia, the only condition of his team’s participation was that community health workers and doctors had to receive training. “We think that is a more long-term, sustainable way of expanding this use of data,” he said.

Returning to the subject of how his work fits into Tableau’s business operations, he explained that in the Zambia project, for example, the idea was to demonstrate what he considered a risky approach and if it worked, it would provide a good story that would inspire others. “If they decide to scale and buy software from one of our competitors, that’s just part of the risk we take,” he said. He added that when people do use Tableau’s products, they are using them because they have impact. “When the use of our product scales, it scales because it is actually helping people make better decisions that help them achieve impact.” What that tells Tableau as a company, he added, is that if his team is successful on the social impact side, the company not only achieves its social impact mission, but it also

creates the potential—not a guarantee—that there will be a demand for Tableau products at some point.

In fact, said Myrick, innovations arising from the Zambia project are now turning into product features that will help all of Tableau’s customers. One innovation, for example, involved adding a texting feature that notifies a clinic director when the data he or she submits do not pass an automated data quality check. As a result, data quality improved by 30 percent in just 4 weeks. Tableau is now investing time in refining this system so it will benefit other customers, said Myrick.

From a social impact perspective, this project has had the added benefit of creating what Myrick called a generation of data champions among government and nongovernmental organization workers. “In Zambia and most of our other projects, they are able to see how you can use data to help you do your job better in various ways, and that increases the impact,” said Myrick. “That turns them into data champions.” This belief in the power of data is reinforced in these projects because the data come back to the people who generate it, rather than going off to the ministry office or to the funder and never being seen again. In fact, he said, delivering data back to the people who generate it, in a way they can use it and benefit from it, seems to improve the quality of data automatically.

DISCUSSION

Katherine Taylor from the University of Notre Dame asked Myrick to elaborate on the concept of the teenager companies and how they fit into these partnerships. Myrick replied that he thinks of most teenager technology companies as being in the pre-initial public offering stage, with anywhere from 1 to 5,000 employees, and a wealth of intellectual capital and products that can solve real problems. However, because of their size and their focus on competing in crowded markets, they do not have the time or resources to engage in the longer discussions needed to build relationships with governments and other large organizations.

As an example, he cited the company Alteryx, whose specialty is data transformation. In this case, the company’s software takes District Health Information Software data, combines it with other data, and configures it into a format from which Tableau’s software can produce reports. “We called them for that specific purpose and they donated their software,” said Myrick. PATH then built its internal capacity to deploy Alteryx’s software. Similarly, Twilio provided 5 years of its messaging services to enable the innovation Myrick described earlier. In each instance, as well as with the other teenager technology company partners, the Tableau Foundation reached into its ecosystem to identify a company with a product

to address a specific on-the-ground need that PATH identified, and then it invited the company to join the project.

One by-product of this process is that Tableau, PATH, and the United Nations are exploring the idea of building a marketplace where smaller companies such as these, which do not have the resources of Microsoft, Oracle, SAP, and other technology titans to sell into the LMIC market, can provide their technology at some prenegotiated price that an LMIC can afford. The hope is that such a marketplace would not only enable small technology companies to engage in those markets and for the information technology people in those markets to access innovative products, but it would also make the procurement process more transparent and perhaps eliminate some of the corruption that often accompanies procurement processes.

Alain Labrique asked Marcelo about his perspective on incentivizing the engagement of large health care provider systems that have no inherent incentive other than a legislative requirement to be interoperable with a government-led registry system when they can function independently. Marcelo replied that in a country such as the Philippines, which has a single-payer health insurance system, the reimbursement system acts as the carrot and stick. In the Philippines, the Philippine Health Insurance Corporation, in partnership with the Department of Health, developed a system that mandates providers to submit their data in a standard format in order to be reimbursed. Such a system, he added, also protects purchasers from being locked into a product that will not work with future products because of an interoperability issue. He acknowledged, though, that getting private-sector providers and insurers to comply with standards will be more difficult in countries that lack some legislative mandate.

Marcelo shared that AeHIN had also developed a Convergence Workshop, a multisector meeting led by the ministry of health, that includes development partners and private vendors. The workshop is structured to establish the leadership of the ministry of health and to encourage the evolution of partnerships that contribute to the ministry’s mission of creating a national health information system. AeHIN has held workshops in Bhutan, Indonesia, Myanmar, and Vietnam, with participants in the initial workshops participating in those held in other countries. The next workshop, he said, will be in Cambodia.

When asked which types of organizations are working in Nigeria, Oyedepo replied that it is a mix of large multinational corporations, small startups, indigenous donor and development organizations, and international development organizations. The problem is not finding organizations that want to work in Nigeria, given its size and population, but that most of the aid that comes in to fund health and technology programs is

designed to strengthen specific programs, not the national system. As a result, the national system is not resilient to shocks.

“One thing that needs to be thought through by donors and development partners in or outside of the country, and even the government, is the need to make the application of technology systemic,” said Oyedepo. In some cases, he said, this will require, as Marcelo noted earlier, going back and creating frameworks and fixing existing systems before introducing a new technology to a broken system. “The sad thing about technology is that, at best, it is an enabler, it optimizes whatever exists,” said Oyedepo. What needs to happen, he added, is for donors and partners to start thinking about how their particular projects fit into the larger context of developing a national system rather than demanding that programs meet certain milestones as quickly and efficiently as possible.

A participant from John Snow, Inc., commented that collaboration is the way to go, but asked what success looks like for these networks given the 10- to 15-year time frame for their development. One way to do that, said Oyedepo, is to break a project into smaller deliverables and report on those in shorter time frames, which he says can lead to the donor renegotiating the project time frame. Also important, he said, is to involve the government at each step along the way to make sure a project continues to fit into the government’s larger objectives and priorities. Myrick said the problem is that the donor is not the customer—the customer is the country’s government and people that a project aims to help. This is why he favors the social business model because it compels the partnerships to treat the intended beneficiaries as the customer, not the people who provide the seed funding for a project. Marcelo added that the convergence workshops, by having donors be participants, reinforce the idea that all activities are designed to support the ministry of health and its goals and not necessarily the short-term goals of the funders or private-sector partners.

Gibbons concluded the discussion by asking the participants to share why they are optimistic about the future, given the challenges to collaboration that were discussed during the panel and more widely during the workshop. Marcelo replied that he is optimistic because his program and Oyedepo’s are starting to work together to create an Asia–Africa governance exchange program to share best practices and elevate the discourse around eHealth. Oyedepo said his optimism stems from the information exchange that happens in true partnerships. Regular reporting leads to the partners encouraging one another. It also provides a sense that accountability is a good thing, something that then leads to a stronger sense of ownership, and thus a stronger reason to continue to collaborate.

Long said her optimism comes from working with people like

Marcelo, Myrick, and Oyedepo, and observing an evolving dialogue in digital health over the last few years that is focused on genuine collaboration. Myrick said that he is encouraged when he hears leaders such as Marcelo and Oyedepo talking about having ministers—and not technology vendors—leading conversations. He added that he is optimistic that the example that USAID and BMGF have set by supporting and promoting PATH’s digital health initiative to end fragmentation will prompt other funders to follow suit.