6

Current Approaches to Examining the Evidence: Key Findings

The National Nutrition Monitoring and Related Research Act of 1990 states that the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA)1 should provide “nutritional and dietary information and guidelines . . . based on the preponderance of the scientific and medical knowledge which is current at the time the report is prepared.”2 As written in the Statement of Task (see Box 1-3), this committee of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies) was requested by Congress to review “(2) how the Nutrition Evidence Library (NEL) is compiled and utilized, including whether NEL reviews and other systematic reviews and data analysis are conducted according to rigorous and objective scientific standards; and (3) how systematic reviews are conducted on longstanding DGA recommendations, including whether scientific studies are included from scientists with a range of viewpoints.”3 To respond to these requests, this chapter summarizes the approach taken by this National Academies committee to review and evaluate the processes used in examining the evidence that underlies the DGA recommendations.

This chapter is divided into sections to reflect the types of analyses traditionally used by the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC):

___________________

1 Refer to Chapter 1, Box 1-1, for an explanation of how the term DGA is used throughout this National Academies report.

2 National Nutrition Monitoring and Related Research Act of 1990, Public Law 101-445, 101st Cong. (October 22, 1990), 7 U.S.C. 5341, 104 Stat. 1042–1044.

3 Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016, Public Law 114-113, 114th Cong. (December 18, 2015), 129 Stat. 2280–2281.

(1) original NEL systematic reviews, (2) existing systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and reports, (3) food pattern modeling, and (4) descriptive data analyses. For each type of analysis, this National Academies committee first considered the types of research questions that are relevant for the DGAC; the types of analysis that are appropriate to address these questions; and how the 2015 DGAC’s review of evidence was conducted. This chapter then discusses ways in which the process can be strengthened or enhanced to best support the DGA in the future. Finally, this National Academies committee considered the necessity for and availability of high-quality data for use in each of the four types of analyses used by the 2015 DGAC.

OVERVIEW OF THE TYPES OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND ANALYSES USED BY THE DGAC

This National Academies committee analyzed the questions answered by the 2015 DGAC and categorized the questions in the DGAC’s evidence review—inclusive of all evidence types—into three broad groupings: eating patterns, prevalence of disease, and relationships between diet and health (see Table 6-1). In some instances, previous DGACs have used multiple analyses for reviewing the evidence to address a specific question.

To understand the prevalence of disease in the overall population, the DGAC asked a series of descriptive questions. Analyses of U.S. population data were used to estimate the number of Americans living with certain chronic diseases.

Questions related to eating patterns included examination of (1) current patterns of food and nutrient consumption in the United States and (2) how changes in food choices would alter dietary intakes. While these areas are related, three main types of questions were addressed (i.e., descriptive, relational, and predictive questions); the 2015 DGAC used

TABLE 6-1 Types of Research Questions Asked and Examples from the 2015 DGAC Scientific Report

| Categories of Questions | Types of Research Questions Asked and Examples from the 2015 DGAC Scientific Report | Analyses Conducted by the 2005, 2010, and 2015 DGACs |

|---|---|---|

| Eating Patterns | ||

| 1a. Examine eating patterns in overall population and population subgroups | Descriptive questions Ex: What are current consumption patterns of nutrients from foods and beverages by the U.S. population? |

|

| Categories of Questions | Types of Research Questions Asked and Examples from the 2015 DGAC Scientific Report | Analyses Conducted by the 2005, 2010, and 2015 DGACs |

|---|---|---|

| 1b. Examine projected changes in eating patterns (may be based on potential DGAC conclusions) | Predictive questions Ex: How well do the USDA Food Patterns meet the nutritional needs of children 2 to 5 years of age, and how do the recommended amounts compare to their current intakes? Given the relatively small empty calorie limit for this age group, how much flexibility is possible in food choices? |

|

| Prevalence of Disease | ||

| 2. Examine prevalence of disease in overall population and population subgroups | Descriptive questions Ex: What is the current prevalence of overweight/obesity and distribution of body weight, body mass index (BMI), and abdominal obesity in the U.S. population and in specific age, sex, race/ethnicity, and income groups? |

|

| Relationships Between Diet and Health | ||

| 3a. Examine relationships between diet and health and disease outcomes of interest (e.g., type of relationship, importance) | Relational questions Ex: What is the relationship between sodium intake and blood pressure in adults? |

|

| 3b. What interrelationships exist between different types of nutrient intakes (e.g., the combined effect of sodium and potassium versus individual effects)? | Ex: What effect does the interrelationship of sodium and potassium have on blood pressure and cardiovascular disease outcomes? |

|

NOTES: This table summarizes approaches the 2005, 2010, and 2015 DGACs have taken in their evidence reviews, including the types of research questions asked. It does not offer all possible types of analyses that could be used to answer these questions. DGAC = Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee; NHANES = National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; USDA = U.S. Department of Agriculture.

four general types of analyses to answer the questions. To evaluate current eating patterns, the 2015 DGAC asked descriptive questions about the food and nutrient intakes of Americans. These were answered using analyses of U.S. population data such as the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). To project the effect of changes in eating patterns, predictive questions were asked to anticipate potential outcomes. These types of questions have been addressed through food pattern modeling, a kind of analysis that predicts the effect of the recommended changes.

Given the DGAC’s mandate to “promote health and prevent disease,” of particular interest and concern for the 2015 DGAC were relationships between diet and health and disease outcomes (including the nature of the relationships, as well as intermediate outcomes) (HHS/USDA, 2015b). Therefore, many of the questions answered by the 2015 DGAC were relational questions. These questions were answered using original systematic reviews, and/or existing systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and reports in the literature.

Methodological Approaches to Different Types of Questions

Over time, the types of analyses used by DGACs to develop the scientific basis for the DGA have evolved. Descriptive data analyses were available for use by the DGAC since the origin of the guidelines, but data on dietary intakes were only formally considered by the DGAC as recently as 2010. Food pattern modeling was available and used to produce recommended intakes of food groups since the 1990 edition. Relationships between diet and health were historically based on ad hoc expert examination of the existing literature. However, as the science of evidence review evolved, more standardized methods of systematic review have been considered and employed in the DGAC’s review of the evidence. The NEL was introduced in the 2010 cycle. The 2015 DGAC used the following types of analyses:

- NEL systematic reviews: Comprehensive reviews of the literature that adhere to established principles, as well as updates of existing systematic reviews

- Existing sources of evidence: Evaluations of sources of evidence such as published systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and reports

- Food pattern modeling: A type of sensitivity analysis that incorporates various data inputs, constraints, goals, and assumptions to inform food patterns and resulting nutrient profiles, as well as to answer various questions regarding the effects of modifications to food patterns

- Descriptive data analyses: A type of analysis used to answer descriptive questions about overall population trends and population subgroups

DGACs have also considered invited expert testimonies and public comments.

ASSESSMENT OF SYSTEMATIC REVIEW METHODS

Systematic reviews provide a synthesis of relevant existing research on a particular topic.4 Systematic reviews are a significant source of evidence for the DGAC. Prior to 2010, DGACs relied on existing reports available in the published literature, or drew conclusions based on their own review of the evidence. The NEL is a program housed in the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion, and it conducts systematic reviews to inform federal nutrition policy and programs (USDA, 2017). It was developed in part to provide support, as well as a structure and protocol, for the DGAC to conduct original systematic reviews (USDA/HHS, 2016).

The use of systematic reviews has varied across cycles with respect to the use of original and existing systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and reports. The 2005 DGAC answered around 44 percent of questions with an evidence-based literature review (17 out of 32 total questions), and roughly the same percentage with existing publications. With the introduction of the NEL in 2010, the number of systematic reviews used by the DGAC increased. During the 2010 cycle, 76 percent of the questions (44 out of 59 total questions) were answered by an original systematic review, while existing publications were used to answer about 12 questions (20 percent). In the 2015–2020 DGA, 25 percent of the questions (23 of 91 total questions) were answered by an original systematic review, while existing publications were used to answer 44 percent of the questions (40 of 91 total questions).5 Notably, systematic review methodology has become increasingly common, and thus more reviews were likely available for use by the DGAC in 2015 than in 2010. Despite some variation across DGA cycles, systematic reviews, both previously existing and conducted de novo, have served as a key source of evidence. The devel-

___________________

4 Systematic reviews are designed to answer a specific question(s). The DGAC process for selecting and refining topics precedes the development of systematic review questions and is described in detail in Chapter 5. Systematic review questions are developed according to the criteria outlined below in Step 1 of the NEL process.

5 These numbers were calculated based on the 2005, 2010, and 2015 DGAC reports. See Appendix C for a complete list of questions answered by the 2015 DGAC.

opment of the NEL has led to centralization and standardization of the systematic review process across the most recent DGA cycles.

Questions That Systematic Reviews Are Intended to Address

Systematic reviews provide important insights into the relationships between diet and health. For example, such questions as “What is the relationship between dietary patterns and risk of cancer?” and “What is the relationship between sodium intake and cardiovascular disease outcomes?” were the subject of two systematic reviews in the 2015 DGAC Scientific Report. This type of question intends to assess the stated relationship between a particular aspect of diet within a defined population, with respect to a particular intervention and defined health outcome, and with consideration for known potential confounders. Using systematic reviews to understand the nature and types of these relationships also means distinguishing between causality and associations, depending on the study types and data available. The quality of the studies available may also limit the ability to make certain inferences, and careful consideration of quality and risk of bias of included studies in systematic reviews is important.

The 2015 DGAC also used systematic reviews to consider the relationships of other factors influencing diet and/or affecting health outcomes of interest. For example, the questions “What is the relationship between neighborhood and community access to food retail settings and weight status?” and “What is the impact of obesity prevention approaches in early care and education programs on the weight status of children ages 2 to 5 years?” consider weight status as a health outcome of interest.

Questions of relationship can also be developed in such a way to assess the effect of a particular dietary factor on a health or disease outcome, including intermediate outcomes. Examples of this type of question include “What effect does the interrelationship of sodium and potassium have on blood pressure and cardiovascular disease outcomes?” from the 2015 DGAC Scientific Report, and, “What are the effects of dietary stearic acid on LDL cholesterol?” from the 2010 DGAC Scientific Report.

According to NEL protocol, systematic review questions are developed and prioritized in advance of the decision to use an existing systematic review, meta-analysis, or report, or to conduct a de novo systematic review. The process of identifying, evaluating, and deciding whether or not an existing systematic review should be included or excluded requires a different set of considerations than conducting an original systematic review (see “Assessment of the NEL Process for Using Existing Systematic Reviews, Meta-Analyses, and Reports” beginning on page 167).

The USDA Nutrition Evidence Library and Its Approach to Conducting Original Systematic Reviews for the DGAC

The NEL is staffed by nutrition scientists and research librarians with systematic review expertise; for both the 2010 and 2015 DGACs, NEL staff provided support for all original (de novo) systematic reviews.

The design of the NEL protocol for original systematic reviews is based on published methodologies from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Cochrane, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, and the Institute of Medicine (IOM) (USDA/HHS, 2016). Standardized methodology and protocols are used for the purpose of promoting transparency, minimizing bias, and ensuring the development of high-quality systematic reviews. For original NEL systematic reviews, the review team is composed of the following:

- A DGAC subcommittee (four to seven members), for the purpose of providing expertise specific to the review topic and knowledge of the field;

- One or more NEL analysts, who assist the DGAC in planning, facilitating, conducting, and documenting the systematic review to ensure alignment with NEL methodology;

- One or more NEL librarians, who manage the development, implementation, refinement, and documentation of the search strategy; and

- NEL abstractors, individuals with advanced degrees in nutrition or a related field, who assist in data extraction and risk of bias assessment.

The size of the systematic review team varies based on the project’s needs, but at a minimum, one librarian and one analyst are assigned a lead role.

NEL librarians and analysts are required to be trained in systematic review methodology. New staff members are required to undergo approximately 150 hours of training over the course of several months before independently performing any of the steps in the systematic review process (USDA/HHS, 2016). NEL abstractors receive approximately 10 initial hours of training from the NEL staff and an email orientation to the specific systematic review project, as well as ongoing training as needed throughout the project. Prior to approval for participation, evidence abstractors are required to disclose potential financial, professional, and intellectual conflicts of interest (USDA/HHS, 2016).

The six steps in the NEL original review process are as follows:

- Topic identification and systematic review question development;

- Literature search, screening, and selection;

- Data extraction and risk of bias assessment;

- Evidence description and synthesis;

- Conclusion statement development and evidence grading; and

- Identification of research recommendations.

The DGAC makes all substantive decisions during each step, while NEL staff assists in executing and documenting those decisions and ensuring that the process adheres to established NEL methodology. Table 6-2 provides an overview of each step in the process, specifying the roles of the NEL staff, DGAC, and tools used. Even for the steps in Table 6-2 that specify the NEL as the primary actor, the DGAC still provides oversight and direction, and reviews and approves products.

Step 1: Topic Identification and Systematic Review Question Development

Topics are identified by the DGAC. During the topic identification process, the DGAC determines additional information about the topic, including the target population, public health outcomes of interest, and relevant references as appropriate.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and USDA suggest topic selection criteria, based on the scope and purpose of the DGAC. These criteria focus on the role of the DGA to inform public health action and policy in promoting population health and reducing the risk of disease (Millen, 2017). Also taken into consideration is the likelihood that the results of including the topic in an evidence review will: “(1) inform decisions about federal public health food and nutrition policies and programs, or (2) represent an area of major public health concern, uncertainty, and/or a knowledge gap that is critical to public health policy” (USDA/HHS, 2016). Both scope and importance are considered in selecting topics.

For each suggested topic, the rationale for review, target population, and public health outcomes of interest are outlined, and the approach for examining the evidence for the topic is recommended by the DGAC. These steps apply to all topics, regardless of the type of analysis used to examine the evidence (i.e., original NEL systematic review; existing high-quality systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and report(s); food pattern modeling; descriptive data analyses).

If requested by the DGAC, the NEL provides support at this initial stage of the evidence assessment by conducting exploratory searches. The goals of exploratory searches are to determine whether sufficient evidence is available to warrant a systematic review, to refine search terms and health outcomes of interest, and to provide information to estimate the

TABLE 6-2 Overview of NEL Systematic Review Steps

| NEL Systematic Review Steps | Primary Actor | Tools Useda |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | ||

| Identify topics | DGAC | N/A |

| Develop questions | DGAC | PICO |

| Prioritize questions | DGAC | N/A |

| Develop analytic framework | DGAC | PICO, key definitions, potential confounders, related questions |

| Step 2 | ||

| Refine inclusion/exclusion criteria | DGAC | N/A |

| Develop search strategy | NEL | N/A |

| Screen and select studies | NEL | N/A |

| Determine inclusion of existing systematic reviews/meta-analyses/reportsb | NEL | AMSTAR |

| Step 3 | ||

| Extract data | NEL | N/A |

| Assess risk of bias | NEL | NEL BAT |

| Step 4 | ||

| Synthesize and evaluate evidence | DGAC | N/A |

| Draft evidence description and synthesis | NEL | N/A |

| Step 5 | ||

| Draft conclusion statement | DGAC | N/A |

| Grade body of evidence/conclusion statement | DGAC | NEL Grading Rubric |

| Step 6 | ||

| Identify research recommendations | DGAC | N/A |

NOTE: AMSTAR = Assessing the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews; BAT = Bias Assessment Tool; DGAC = 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee; N/A = not applicable; NEL = Nutrition Evidence Library; PICO = population, interventions/exposures, comparators, and intermediate and/or health or dietary outcomes of interest.

a For the purposes of this table, this column notes only specialized tools. NEL protocol specifies the methods used at each of these steps, which are outlined in detail in the text.

b If no existing systematic reviews, meta-analyses, or reports are identified in the literature search, this step is omitted.

time and resources needed for a systematic review on a specific topic. It is not to provide details on results or conclusions.

For topics that are selected to be addressed with systematic reviews—either original NEL systematic reviews, or existing high-quality reports when available—questions are developed by the DGAC with assistance from federal staff according to the PICO (population, intervention/exposure, comparator, and outcome of interest) framework. The PICO framework outlines the following elements of interest to be included in the question: target population and subpopulations, the intervention and/or exposure, the main comparator, and selected outcomes. Systematic review questions are reviewed and further refined in an iterative process, integrating input from the DGAC to ensure appropriate focus and specificity. The subsequent development of an analytic framework is intended to ensure that the final systematic review question(s) considered critical elements that may have affected the outcome. In addition to the PICO elements, the analytic framework for each systematic review includes key definitions, potential confounders, and a list of all systematic review questions for a particular topic, if more than one was asked. The analytic framework serves as a visual representation of the overall scope of the project and is available publicly during DGAC meetings, online after DGAC meetings, and once the systematic review is completed and the DGAC Scientific Report is released.

Step 2: Literature Search, Screening, and Selection

Search For each systematic review project, the lead NEL librarian, working in collaboration with the DGAC and NEL analyst(s), is responsible for developing a search strategy to identify relevant literature and for documenting the search terms, electronic databases searched, and appropriate search refinements.

First, DGAC subcommittees establish a priori inclusion and exclusion criteria for each systematic review based on a set of standard criteria developed by the NEL for the purposes of promoting consistency across systematic reviews and ensuring relevance to the U.S. population. These criteria can be revised by the DGAC subcommittee members if needed based on the topic of the systematic review to address any unique considerations. For example, questions examining the relationship between community food environments or food access and weight status are limited to only include U.S. populations, but for questions on relationships between dietary patterns and cancer, the population is expanded to include individuals from countries with a high or very high human development index (as defined according to the 2012 Human Development Index) (HHS/USDA, 2015b). To promote objectivity and minimize opportunity

for bias, any post hoc revisions to the criteria are discouraged by the NEL protocol, and if changes have to be made, the date and justification for the revision are documented in the search strategy.

The NEL inclusion and exclusion criteria cover study design, risk of bias, language, publication status, and health status of study subjects, along with the rationale for selections (USDA/HHS, 2016). Specifically, the standard criteria for DGAC systematic reviews include studies published in English in peer-reviewed journals in generally healthy populations, including populations with elevated chronic disease risk, or a mix of individuals with and without the disease or health outcome of interest. Studies are excluded if they were conducted in exclusively diseased populations or nongeneralizable subsets of the population, were unpublished or in the grey literature, or were published in languages other than English. Studies are not excluded based on a risk of bias assessment, although this is considered in later grading of the overall quality of the evidence (USDA/HHS, 2016). Study designs that are included and excluded may be dependent on the most appropriate design feasible for addressing a particular topic or question. However, standard NEL protocol states that randomized and nonrandomized controlled trials, prospective and retrospective cohort studies, case-control studies, and pre/post studies with a control are included, while cross-sectional studies, uncontrolled studies, pre/post studies without a control, and narrative reviews are excluded (USDA/HHS, 2016). Existing systematic reviews and meta-analyses are identified in a duplication assessment and may be used at the discretion of DGAC subcommittees to replace or augment an original NEL systematic review.

To test the search strategy and identify any potential errors, the NEL librarian performs a preliminary search in PubMed, using PubMed operators and search terms, and previews the results. The search strategy is then peer reviewed by another NEL librarian for the following elements:

- “The accuracy of translating the research questions into search concepts and terminology;

- Proper use of search operators, fields, limiters or filters, and spelling of syntax of search terms/strings;

- The accuracy of adapting the search strategy for each database;

- Inclusion of relevant subject headings such as Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) with free-text terms; and

- Provision of additional relevant search terms and/or original databases” (USDA/HHS, 2016).

The NEL librarian makes any necessary revisions during the peer-review process, shares the search strategy with the DGAC subcommittee for

review, and subsequently finalizes the search strategy after all additional revisions noted by the DGAC subcommittee are made. PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane are the standard databases searched, but other topic-specific databases may be searched depending on the research question (USDA/HHS, 2016). All databases searched are listed in the search plan and results. The final search is conducted in the selected electronic databases.

Screening The results of the search are independently screened by two NEL analysts via title, abstract, and full-text review. The goal of screening is to review the search results and determine whether each article meets the inclusion and exclusion criteria. A third analyst or member of the DGAC is available to resolve conflicts between the two analysts.

Selection The resulting list of included and excluded articles is reviewed and approved by the DGAC subcommittee. A manual search of the reference sections of included articles is also performed to ensure all relevant articles are included, and to identify any potential gaps in the search.

Duplication assessment Depending on the topic and literature identified, NEL staff can conduct a duplication assessment to identify any existing high-quality systematic reviews, meta-analyses, or reports that answer the systematic review topic or question of interest. Existing systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and reports may be used to either replace an original systematic review or to supplement a systematic review as an additional source of evidence.

If an existing systematic review, meta-analysis, or report is identified during the search and screening process, the DGAC subcommittee is responsible for determining if and how it should be used, based on the report’s relevance to the systematic review question of interest, the quality of the report, the timeliness of the report, and with consideration for reference overlap. The assessment is based on PICO elements, AMSTAR rating, and the date range of the existing systematic review (see “Assessment of the NEL Process for Using Existing Systematic Reviews, Meta-Analyses, and Reports” beginning on page 167 for more information). If multiple existing reports are identified on the same topic and the conclusions are similar, the NEL can combine them in consideration of overall evidence; if conclusions differ, they can be used for background information, but are not deemed an appropriate source of evidence. If no existing high-quality reports are identified, the NEL proceeds with an original systematic review on the identified topic and questions.

Step 3: Data Abstraction and Risk of Bias Assessment

In preparation for the review and summary of the evidence, data relevant to the systematic review question are extracted and risk of bias is assessed for each article included in a systematic review. A standardized evidence extraction form is developed by the NEL analyst and approved by the DGAC subcommittee to ensure all relevant data are collected. These forms are organized generally by study characteristics, participant characteristics, exposure(s)/independent variable(s), outcome(s)/dependent variable(s), limitations/risks of bias, funding, and related articles. Specific instructions are also provided to ensure all relevant information is collected (e.g., for Dietary Assessment Method, example instructions may specify: “enter name and/or type of instrument used and a brief description of tool, if it was validated for the study sample, number of data collection points, and which data points were used for diet assessment”) (USDA/HHS, 2016). Data extraction can be done with assistance from NEL abstractors.

After completing the data extraction, risk of bias (internal validity) in individual studies is assessed using the NEL Bias Assessment Tool (BAT). The NEL BAT was developed to assess the risk of bias of individual studies included in NEL systematic reviews, and is based on existing risk of bias tools, including those developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and Cochrane, and follows a question/answer format (Higgins and Green, 2011; USDA/HHS, 2016; Viswanathan et al., 2012, 2013; West et al., 2002). The tool is designed to assess four types of bias, including

- Selection bias, through assessment of inclusion/exclusion criteria, recruitment, allocation of participants, and baseline distribution of confounders;

- Performance bias, through assessment of adherence to study protocol by the participants and investigators, unplanned concurrent exposures, and blinding of the participants and investigators;

- Detection bias, through assessment of blinding of the outcome assessors, outcome measures, and statistical methods; and

- Attrition bias, through assessment of follow-up length and attrition (high/differential).

Each of these assessments is facilitated by a set of targeted questions specific to randomized controlled trials, nonrandomized controlled trials, or observational studies. For example, to assess blinding of participants on randomized or nonrandomized controlled trials, the NEL BAT question is “Were participants blinded to their intervention or exposure status?” Each question can be answered with one of four responses: yes,

no, cannot determine, and not applicable. NEL protocol specifies that “yes” or “no” responses should be selected if sufficient information is provided in the study to clearly indicate the answer to the question; if no or insufficient information is available in the study, “cannot determine” should be selected; and “not applicable” should be selected if the question is not applicable to the study. For quality control purposes, the NEL BAT is completed in a dual process where both the evidence abstractor and an NEL analyst independently complete the bias assessment. Any conflicts identified are to be resolved by the abstractor and analyst, with assistance from another NEL staff member, if needed (USDA/HHS, 2016).

The analyst combines the extracted data and limitations identified via the NEL BAT into a spreadsheet referred to as the evidence grid to assist the DGAC subcommittee’s review of the evidence (USDA/HHS, 2016).

Step 4: Evidence Description and Synthesis

The DGAC subcommittee reviews the evidence grid and the full-text manuscripts of the articles identified in the search. This review is facilitated by a series of probing questions provided by the NEL analyst, referred to as the evidence portfolio worksheet, which are independently completed by each DGAC subcommittee member. These questions vary in their focus and aim and are intended to aid the DGAC members in comparing and contrasting the studies reviewed, and to assist with subsequent development of a conclusion statement along with a grade of the overall quality of the evidence. Some of the questions are intended to evaluate the characteristics affecting the quality of the study and potential considerations, and include the following:

- “Whether the reported effects of a study are likely to be the true effects of the intervention/exposure,

- Whether the sample size of a study is sufficient to avoid type I and II errors,

- Whether a study is designed to directly examine the link between the intervention/exposure and the outcome(s) of interest in the systematic review question, and

- Whether a study is generalizable to the U.S. population of interest” (USDA/HHS, 2016).

Other questions focus on the specific intervention/exposure and outcome(s) of interest for the systematic review. Study limitations, consistency of results, methodological differences resulting in disagreement in outcomes, significance of results, and reliability across multiple independent research groups are also noted.

The NEL analyst compiles information from the DGAC subcommittee’s review of the evidence portfolio to facilitate drafting of the evidence description and synthesis by a DGAC member(s) or the analyst, which includes descriptive information about the review and a summary of findings. The draft synthesis of evidence is reviewed by the DGAC subcommittee; a minimum of three subcommittee members are required to provide feedback before the synthesis can move forward (USDA/HHS, 2016). The synthesis of evidence generally compares and contrasts the interventions/exposures and outcome(s) of interest, methodology, and results. Also included in the final evidence synthesis is a discussion of the themes of the systematic review question, an overview table providing a summary of the results and key study characteristics, an assessment of the body of evidence according to the aspects outlined in the NEL grading rubric, and the resulting research recommendations and rationale.

Step 5: Conclusion Statement Development and Evidence Grading

The collection, description, and synthesis of evidence are subsequently used by the DGAC subcommittee to develop a conclusion statement in response to the systematic review question. Conclusion statements are written in a clear and concise manner and include relevant information important for consideration, including a statement acknowledging general agreement among the studies on which the conclusion was based, and/or an explanation of any areas of disagreement. Per NEL protocol, conclusion statements are not to address areas outside of the body of evidence reviewed and are not intended to express implications. Drafting conclusion statements, as with the evidence description and synthesis, is an iterative process involving both DGAC subcommittee and NEL staff. The DGAC subcommittee’s role is to ensure appropriate interpretation and communication of evidence, while the NEL staff’s role is to review draft conclusions to ensure they met the protocol. If discussions throughout the evidence synthesis and drafting of conclusion statements necessitates clarifications or changes to the evidence portfolio, these are made by the NEL staff as appropriate.

Each conclusion statement is accompanied by a grade of the strength of the evidence supporting the conclusion; the grade is not applicable to individual studies. The grade is determined by the DGAC subcommittee according to specific criteria laid out by the NEL and based on five elements: internal validity, adequacy, consistency, impact, and generalizability.

- Internal validity refers to the “likelihood that the reported effects are the true effects of the intervention/exposure and not over- or

-

underestimates resulting from bias due to study design or conduct” and is based on information gathered in completing the NEL BAT (USDA/HHS, 2016).

- Adequacy of the evidence is determined based on the number of “studies overall, studies by independent research groups, studies with sample sizes that are sufficient to avoid type I and II errors, and participants overall” (USDA/HHS, 2016).

- Consistency of the evidence is judged on three elements of the findings: “(1) direction, (2) size of effect/degree of association, and (3) statistical significance” (USDA/HHS, 2016).

- Impact of the evidence is determined by: “(1) the directness with which the study designs examine the link between the intervention/exposure and outcome of interest in the systematic review question, (2) the statistical significance, and (3) the practical/clinical significance” (USDA/HHS, 2016).

- Generalizability of the evidence to the U.S. population is considered with regard to the study samples and the intervention/exposure and outcomes studied.

For each of these five elements, the DGAC determines whether the overall body of evidence in each area is strong, moderate, or limited, or whether a grade is not assignable. Each DGAC subcommittee member evaluates the body of evidence and assigns a grade for each of those elements independently, and then differences are noted and discussed among the DGAC subcommittee members. Through discussion, the DGAC subcommittee arrives at a grade for the conclusion statement, reflective of its evaluation of the overall body of evidence as outlined in the NEL grading rubric. The grades used for conclusion statements also fall into one of these four categories: strong, moderate, limited, and grade not assignable (see Table 6-3). Draft and final conclusion statements and grades are presented at public meetings.

Step 6: Identification of Research Recommendations

Research recommendations are initially developed and drafted during the evidence description and synthesis step to reflect gaps and/or limitations in the body of evidence, but can be revised and updated to reflect the continued discussions concerning conclusions and grading of evidence before being finalized. Emerging topics in particular can be included in the DGAC Scientific Report with a rationale describing the need for additional research.

TABLE 6-3 Description of Grades for Conclusion Statements Used by the USDA Nutrition Evidence Library

| Grade | Description |

|---|---|

| I—Strong | The conclusion statement is substantiated by a large, high-quality, and/or consistent body of evidence that directly addresses the question. There is a high level of certainty that the conclusion is generalizable to the population of interest, and it is unlikely to change if new evidence emerges. |

| II—Moderate | The conclusion statement is substantiated by sufficient evidence, but the level of certainty is restricted by limitations in the evidence, such as the amount of evidence available, inconsistencies in findings, or methodological or generalizability concerns. If new evidence emerges, there could be modifications to the conclusion statement. |

| III—Limited | The conclusion statement is substantiated by insufficient evidence, and the level of certainty is seriously restricted by limitations in the evidence, such as the amount of evidence available, inconsistencies in findings, or methodological or generalizability concerns. If new evidence emerges, there could likely be modifications to the conclusion statement. |

| IV—Grade not assignable | A conclusion statement cannot be drawn due to a lack of evidence or the availability of evidence that has serious methodological concerns. |

SOURCE: USDA/HHS, 2016.

Availability and Accessibility of Systematic Reviews

Public availability of original systematic reviews is part of the NEL protocol. For example, the NEL systematic reviews are documented in their entirety and, following the completion of the review and the publication of the DGAC Scientific Report, are posted on the NEL website (NEL. gov) to promote transparency, accessibility, and reproducibility. Systematic reviews conducted for the DGAC are discussed at DGAC public meetings. Throughout the 2015 DGAC’s deliberations, public comments were accepted, and comments about the systematic reviews under way were welcomed and reviewed by the 2015 DGAC. The completed evidence portfolio that is posted online following the publication of the DGAC Scientific Report includes

- A conclusion statement;

- A grade of the overall quality of evidence;

- Key findings;

- Research recommendations;

- Evidence summaries giving the description and synthesis of the evidence along with the risk of bias assessment, references, and research recommendations;

- An analytic framework, including the systematic review question(s); and

- Search plan and results, including search parameters, selection criteria, and the final list of included and excluded articles, with brief explanations of reasons for exclusion (USDA/HHS, 2016).

The NEL staff drafts a technical abstract for each systematic review, which is posted on the NEL website along with the details of the full systematic review. The technical abstract is designed to provide key details of the systematic review in an easily accessible and standard format, similar in nature to a technical abstract prepared for peer-reviewed publications or scientific meetings, but longer and including more detail. Technical abstracts are reviewed by the DGAC subcommittee members before posting. Each technical abstract is titled with the systematic review question it describes, and includes five sections: background, conclusion statement, methods, findings, and discussion. Within these sections, key details of the systematic review are described, including the rationale and objective, data sources, study eligibility criteria, participants, interventions, study appraisal, synthesis methods, results of the systematic review and appraisal of the body of evidence along with the grade of the conclusion statement, and limitations and implications of key findings (USDA/HHS, 2016).

Approach to Non-DGAC Systematic Reviews

The NEL was created to support the DGAC, as well as conduct nutrition-related systematic reviews for federal partner agencies, such as those within USDA and HHS. As a result, the NEL has two separate protocols for conducting systematic reviews: one for DGAC-requested systematic reviews, and one for non-DGAC systematic reviews.6 The two protocols have many similarities and use the same steps, but there are key differences.

The fundamental difference between the two protocols is that for DGAC-requested systematic reviews, the DGAC is the approver and “authors” the systematic review (USDA/HHS, 2017). In the protocol for non-DGAC systematic reviews, the NEL authors the work and relies on a technical expert collaborative to provide domain expertise. The technical

___________________

6 In this discussion, details of the steps for the non-DGAC systematic review protocol were derived from two reports (USDA, 2012, 2014).

expert collaborative reviews key decisions and provides technical advice as needed (USDA, 2012, 2014). This difference drives much of the variation at the procedural level (e.g., key decisions made by the DGAC are instead made by the NEL).

Other key differences between the two protocols include the tools used. In Step 3, data extraction and risk of bias assessment, the protocol for DGAC systematic reviews employs the NEL BAT to evaluate bias (USDA/HHS, 2016). The non-DGAC systematic review protocol uses the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Research Design and Implementation Checklist to assess methodological rigor7 (USDA, 2012, 2014). To conduct Step 5, developing conclusion statements and grading the evidence, different sets of criteria are used to evaluate strength of the body of evidence. The DGAC systematic review protocol employs the criteria of internal validity, adequacy, consistency, impact, and generalizability (USDA/HHS, 2016). The non-DGAC systematic review protocol, however, uses criteria adapted and validated by the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: quality, quantity, consistency, generalizability, and public health impact (USDA, 2012, 2014).

Evaluation of the NEL Original Systematic Review Process

Several organizations have developed guidance on conducting systematic reviews, including AHRQ, Cochrane, and the Institute of Medicine, which were all cited in the development of the NEL protocol (USDA/HHS, 2016). To assess the NEL process, the systematic review process from the 2015 DGAC Scientific Report was outlined by this National Academies committee according to systematic review steps adapted from the report Finding What Works in Health Care: Standards for Systematic Reviews (IOM, 2011). These steps, as well as the roles of the NEL and DGAC in the process, are described in detail in Table 6-4. This National Academies committee reviewed each step in the systematic review process. Although the standards presented in Table 6-4 are aspirational and will likely not all be met in every systematic review, they do highlight several opportunities for improvement in the NEL de novo systematic review process, as discussed in the next section.

Findings

Original systematic reviews can help the DGAC answer questions regarding the relationship between diet and health if a synthesis of the

___________________

7 The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics’ Research Design and Implementation Checklist uses the quality ratings of positive, neutral, or negative.

TABLE 6-4 Description of the Roles of the NEL and DGAC in the 2015 NEL Process Related to Conducting Systematic Reviews

| Systematic Review Step | Role of NEL | Role of 2015 DGAC |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Establish a team with appropriate expertise and experience to conduct the systematic review. |

|

|

| 1.1 Include expertise in pertinent clinical content areas. |

|

|

| 1.2 Include expertise in systematic review methods. |

|

|

| Systematic Review Step | Role of NEL | Role of 2015 DGAC |

|---|---|---|

| 1.3 Include expertise in searching for relevant evidence. |

|

|

| 1.4 Include expertise in quantitative methods. |

|

|

| 1.5 Include other expertise as appropriate. |

|

|

| 2. Manage biases and conflicts of interest (COIs) of the team conducting the systematic review. | (described below) | (described below) |

| 2.1 Require each team member to disclose potential COI and professional or intellectual bias. |

|

|

| Systematic Review Step | Role of NEL | Role of 2015 DGAC |

|---|---|---|

| 2.2 Exclude individuals with a clear financial conflict. |

|

|

| 2.3 Exclude individuals whose professional or intellectual bias would diminish the credibility of the review in the eyes of the intended users. |

|

|

| 3. Ensure user and stakeholder input as the review is designed and conducted. | Information about the design and conduct of systematic reviews was discussed during public meetings and made available at https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines.a | |

| 3.1 Protect the independence of the review team to make the final decisions about the design, analysis, and reporting of the review. | Public comments about the systematic review design and conduct were received and reviewed by the 2015 DGAC. | |

| Systematic Review Step | Role of NEL | Role of 2015 DGAC |

|---|---|---|

| 4. Manage bias and COI for individuals providing input into the systematic review. | Public comments were accepted throughout the 2015 DGAC’s deliberations, and submitters were required to provide their affiliation. Federal staff reviewed every comment and filtered out any duplicate, blank, or irrelevant comments. | |

| 4.1 Require individuals to disclose potential COI and professional or intellectual bias. | Not reported. | |

| 4.2 Exclude input from individuals whose COI or bias would diminish the credibility of the review in the eyes of the intended user. | Not reported. | |

| 5. Formulate the topic for the systematic review. | (described below) | |

| Systematic Review Step | Role of NEL | Role of 2015 DGAC |

|---|---|---|

| 5.1 Confirm the need for a new review. |

|

|

| Systematic Review Step | Role of NEL | Role of 2015 DGAC |

|---|---|---|

| 5.2 Develop an analytic framework that clearly lays out the chain of logic that links the health intervention to the outcomes of interest and defines the key questions to be addressed by the systematic review.b |

|

|

| 5.3 Use a standard format to articulate each question of interest.b |

|

|

| 5.4 State the rationale for each question.b |

|

|

| 5.5 Refine each question based on user and stakeholder input.b |

|

|

| 6. Develop a systematic review protocol. | (described below) | (described below) |

| 6.1 Describe the context and rationale for the review from both a decision-making and research perspective. |

|

|

| Systematic Review Step | Role of NEL | Role of 2015 DGAC |

|---|---|---|

| 6.2 Describe the study screening and selection criteria (inclusion/exclusion criteria). |

|

|

| 6.3 Describe precisely which outcome measures, time points, interventions, and comparison groups will be addressed. |

|

|

| Systematic Review Step | Role of NEL | Role of 2015 DGAC |

|---|---|---|

| 6.4 Describe the search strategy for identifying relevant evidence. |

|

|

| 6.5 Describe the procedures for study selection. |

|

|

| Systematic Review Step | Role of NEL | Role of 2015 DGAC |

|---|---|---|

| 6.6 Describe the data extraction strategy. |

|

|

| 6.7 Describe the process for identifying and resolving disagreement between researchers in study selection and data extraction decisions. |

|

|

| 6.8 Describe the approach to critically appraising individual studies. |

|

|

| Systematic Review Step | Role of NEL | Role of 2015 DGAC |

|---|---|---|

| 6.9 Describe the method for evaluating the body of evidence, including the quantitative and qualitative synthesis strategies. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Systematic Review Step | Role of NEL | Role of 2015 DGAC |

|---|---|---|

| 6.10 Describe and justify any planned analyses of differential treatment effects according to patient subgroups, how an intervention is delivered, or how an outcome is measured.b |

|

|

| 6.11 Describe the proposed timetable for conducting the review. |

|

|

| 7. Submit the protocol for peer review. | The protocol for individual systematic reviews was not submitted for peer review. | |

| 7.1 Provide a public comment period for the protocol and publicly report on disposition of comments. | A public comment period was not explicitly provided for each protocol. Public comments are accepted at any time and on any topic throughout the DGAC’s review of the evidence. | |

| Systematic Review Step | Role of NEL | Role of 2015 DGAC |

|---|---|---|

| 8. Make the final protocol publicly available, and add any amendments to the protocol in a timely fashion. | The final protocol was posted on NEL.gov after completion of the review and publication of the DGAC report. | |

NOTES: This table describes the NEL systematic review protocol as based on the 2015 DGAC process. The numbered systematic review steps are adapted from the Institute of Medicine report Finding What Works in Health Care: Standards for Systematic Reviews. The systematic review team was considered to include NEL staff, abstractors, and the DGAC members. DGAC members were not considered to be users/stakeholders. DGAC = 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee; N/A = not applicable; NEL = Nutrition Evidence Library; OGE = Office of Government Ethics; PICO = population, intervention/exposure, comparator, and outcome of interest; USDA = U.S. Department of Agriculture.

a The NEL has established standard processes (e.g., inclusion and exclusion criteria) to help promote consistency across NEL reviews and to ensure that the evidence being considered in each systematic review is applicable to the U.S. population and relevant to public health- and nutrition-oriented policies and programs. These standard processes have been reviewed and informed by federal stakeholders to ensure policy relevance.

b This standard was adapted to apply to the NEL process.

SOURCES: DGAC, 2014; HHS/USDA, 2013; IOM, 2011; USDA/HHS, 2016.

evidence does not already exist. The utility of original systematic reviews depends on the availability of high-quality studies that are implemented appropriately to ensure impartiality of the reviews. The DGAC protocol could be better structured to support independence of NEL de novo systematic reviews.

The roles of the NEL staff and the DGAC are not clearly delineated and overlap at many steps of the systematic review protocol, potentially limiting the objectivity of results. For example, in evaluating the body of evidence, the DGAC’s process for synthesizing evidence and drafting conclusion statements appears to be facilitated by the NEL staff (i.e., NEL staff develops probing questions for the DGAC’s review of the evidence as well as compiles information received from the DGAC), but the statements are both “drafted” by the DGAC and then “reviewed” by the DGAC. The position of the DGAC as the driver of each step in the systematic review process, from the designing of the search strategy to the grading of the body of evidence, does not consistently promote an independent process. This National Academies committee’s evaluation

also identified the challenge of combining a systematic review process with the process for developing DGA recommendations, as best practices have shown that development of guidelines generally requires a more thorough separation of steps. While still allowing for the necessary iterations and communication between DGAC and NEL staff, this National Academies committee believes there is an opportunity to limit the overlap in roles and ensure the necessary expertise is included appropriately in each step by redesigning the process to clearly delineate the roles of both the DGAC and the NEL staff (see Chapter 4).

Because systematic reviews synthesize the evidence presented in individual studies, it is critical that the primary studies are of high quality. Nutrition studies present several methodological challenges, one in particular being self-reported dietary intake data. Because methods for acquiring dietary intake data vary and have the potential to introduce bias into the systematic review outcomes, they should be taken into account in the development of inclusion/exclusion criteria and appropriately managed in analyses whenever possible (see Box 4-4 for a discussion on using self-reported dietary intake data).

Throughout the entire process of conducting systematic reviews, it is unclear how and with what frequency NEL methods are updated. For example, since the NEL BAT was developed, other organizations have made several improvements in assessing the risk of bias in systematic reviews (Higgins and Green, 2011; Viswanathan et al., 2012). However, these updates have not yet been reflected in the NEL BAT. Additionally, while NEL de novo systematic reviews are publicly available, they are not peer reviewed. Maintaining up-to-date methods for conducting systematic reviews in a rapidly evolving field depends on collaboration with outside organizations and implementing ongoing training in best practices.

In addition, appropriately interpreting the results of systematic reviews, and subsequently integrating these results with other analyses, is an important element in developing conclusions. The interpretation of results and integration of analyses are subjective and require careful consideration. Whereas many steps are in place earlier in the NEL systematic review process to help identify potential limitations in the data available (e.g., inclusion/exclusion criteria, risk of bias assessment), it is unclear how these limitations are taken into account in the interpretation of results.

Conclusion

Overall, the NEL process for conducting original systematic reviews is thorough and adheres to several of the existing systematic review standards in the field. However, the overall protocol needs to be strengthened

to improve the efficiency of the NEL process and minimize the introduction of bias. Clear delineation of the roles of individuals and groups involved at various steps in the NEL process are key to developing appropriate conclusions. The NEL ought to use the most appropriate, validated, and standardized methods whenever possible. Ensuring up-to-date methods are adopted and implemented in the NEL process depends on engaging in ongoing training and collaboration efforts with other organizations conducting systematic reviews, and could increase the usefulness of the NEL. Systematic reviews including observational studies in particular will need to be carefully evaluated in the interpretation of results and development of conclusions.

ASSESSMENT OF THE NEL PROCESS FOR UPDATING SYSTEMATIC REVIEWS

Because the NEL has only been used to support two editions of the DGAC Scientific Report, the only opportunity to update systematic reviews conducted previously by the NEL was in the 2015 DGAC. In one instance, the update combined two questions into one and expanded the terminology around the exposure of interest in the search to broaden the scope of the systematic review, while keeping the target population and outcomes the same. In the other instances, the same systematic review was repeated with updated search dates for the purpose of capturing articles published after the original systematic review was conducted. Updates of NEL systematic reviews were conducted and documented according to NEL de novo systematic review methods (HHS/USDA, 2015b). Methods for conducting an update to an existing systematic review not original to the NEL will be discussed in the assessment of existing systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and reports.

Findings

Systematic reviews can be updated to take into account new evidence since the last review was conducted. The NEL process for updating systematic reviews reflects the process for original systematic reviews, and the findings identified for conducting original systematic reviews apply also to the process for updating systematic reviews.

In the 2015 DGAC Scientific Report, a clear explanation of why a decision was made to update or not update a systematic review was not publicly available. Updating systematic reviews can be done for a number of reasons and takes several forms (AHRQ, 2014; Garner et al., 2016; Higgins and Green, 2011). In some cases, such as abstracting new data or significantly adjusting the methods used, updating a systematic review

can require more resources than conducting a de novo review. Reasons to update a systematic review could include any one or multiple of the following scenarios:

- The systematic review question to be answered and the methods to be used remain unchanged, but the review does not include recently published studies on the topic. This gap requires adding recently published studies. This approach also assumes that either the results or the abstracted data from previous systematic reviews are available so that quantitative analyses could be performed, if needed.

- If the systematic review question is changed (different from an existing systematic review), it may require abstracting new data from publications used in previous systematic reviews. An outcome of interest or metric may also change (e.g., measurement of dietary intake). In this case, a new search may or may not be needed.

- Methods used in systematic reviews also evolve (e.g., grading of evidence, the use of different types of self-reported dietary data); adhering to the latest standards in performing an update sometimes requires using data abstracted from primary publications in a previous systematic review.

Conclusion

It was not clear why the 2015 DGAC chose to update some systematic reviews and not others. Updates of NEL systematic reviews generally ought to be conducted on a needs-based approach and in accordance with the NEL systematic review protocol for de novo systematic reviews. Regardless of the reason to update a systematic review, an update needs to consider all relevant research. Updating a systematic review may require collecting additional data or performing new analyses. As a result, newly published studies may be added or previously included studies may be excluded based on refined methods. This includes previously appraised research, because advances in knowledge about mechanisms of action, interactions of nutrients, or other factors that affect the outcome may reflect new understandings and could be integrated into a new conclusion statement.

Because new information and publications often drive updates, ongoing surveillance of literature is necessary to keep systematic reviews up to date and minimize duplication of efforts. Ongoing surveillance can also identify existing systematic reviews that may replace the need to conduct an update of a systematic review.

ASSESSMENT OF THE NEL PROCESS FOR USING EXISTING SYSTEMATIC REVIEWS, META-ANALYSES, AND REPORTS

Many groups around the world are now conducting systematic reviews, often on the same topic. Because systematic reviews require significant amounts of time, expertise, and costs to conduct, a search should be made to identify existing and ongoing systematic reviews before a new systematic review is undertaken. With limited resources, it would be advantageous to leverage existing systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and reports to minimize unnecessary replication of efforts and to share results with others.

However, existing systematic reviews may not fully address the question or population of interest, they may be outdated, or they may not meet current methodological standards. Furthermore, the quality of the systematic reviews—and hence their reliability—may vary. These concerns can make use of existing systematic reviews challenging but do not necessarily invalidate these systematic reviews. The concerns must be carefully analyzed and the challenges in using them understood. If a decision is made to proceed with using existing systematic reviews, documenting the rationale and explaining how any challenges are mitigated provides transparency. Documenting the reasons that existing systematic reviews have been assessed but not included will assist in reconciling potential differences in the results across different systematic reviews.

DGAC Approach to Using Existing Systematic Reviews, Meta-Analyses, and Reports

In addition to conducting original systematic reviews, the DGAC has used existing systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and reports to answer its questions. The 2015 DGAC was the first committee to develop and document a standardized process and criteria for including existing systematic reviews. The process paralleled several of the steps in the de novo NEL systematic review process.

Identifying Existing Systematic Reviews, Meta-Analyses, and Reports

As systematic review questions were developed and prioritized, the DGAC collaborated with the NEL to develop an analytic framework. At this point, before the literature search and screening begins, existing systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and reports may have been identified a priori by DGAC subcommittee members aware of current literature. The 2015 DGAC also requested literature and references on specific topics through public comments. If a report from an authoritative source was identified and met the criteria for inclusion, a literature search was still

conducted according to NEL protocol to identify any additional reports on the topic. Existing reports may also have been identified during a duplication assessment in the early stages of the literature screening and selection process in preparation for a de novo systematic review (USDA/HHS, 2016). In all cases, the existing reports were required to meet the criteria for inclusion.

Criteria for Inclusion

Existing systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and reports were assessed by the NEL and the DGAC to determine if they met the predetermined inclusion/exclusion criteria. In some cases, federal DGAC support staff other than the NEL supported the DGAC in its review of existing systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and reports. The DGAC based its determination on four criteria: (1) the relevance to the systematic review question of interest, (2) the quality of the report, (3) the timeliness, and (4) reference overlap, if multiple systematic reviews were identified.

The relevance to the systematic review question was determined through comparison of the existing report to the established scope of the question outlined in the analytic framework, including PICO stipulations. Inclusion and exclusion criteria used in the existing report were also compared to those outlined for the question to judge relevance. For the 2015 DGAC, the methodological quality of the existing report was evaluated based on the AMSTAR tool, which considers 11 areas of methodological quality elements to assess.8 In the AMSTAR tool, a systematic review receives 1 “point” for each item appropriately fulfilled, with a total score of 11 possible. To meet the inclusion criteria set by the DGAC in 2015, systematic reviews and/or meta-analyses must have scored 8 or higher (USDA/HHS, 2016). Timeliness of the systematic review was based on whether the date range set in the inclusion/exclusion criteria for the existing systematic review matched the date range set in the search strategy for the systematic review question of interest. In cases where multiple existing reports were identified, the references lists were examined for overlap. If individual studies overlap between system-

___________________

8 These 11 criteria are (1) a priori research design established, (2) study selection and data extraction completed by two independent reviewers, (3) comprehensive review of literature conducted, (4) status of publication defined in inclusion criteria, (5) list of included and excluded studies provided, (6) characteristics of included studies provided, (7) scientific quality of included studies assessed and documented, (8) scientific quality of included studies considered in analysis and conclusions drawn, (9) appropriate methods applied for combining findings of studies, (10) assessment of the likelihood of publication bias included, and (11) conflict of interest in included studies and systematic review noted (Shea et al., 2007).

atic reviews, care was taken to ensure that the individual studies were not included multiple times, to reduce the potential for overestimating results (USDA/HHS, 2016).

Evidence Summary and Synthesis

If eligible for inclusion, a summary and synthesis of the evidence from existing reports was developed by federal DGAC support staff. In some cases, targeted questions may have been prepared by the federal staff to facilitate the DGAC members’ identification of themes and key findings from the systematic reviews. The review of evidence specific to each systematic review question was outlined in the 2015 DGAC Scientific Report (at the same level of detail as with original systematic reviews, including a conclusion statement and grade, implication statement, and summary of the review of evidence), and more detailed evidence descriptions were provided in appendixes to the 2015 DGAC Scientific Report (HHS/USDA, 2015b). Although the information provided in the 2015 DGAC Scientific Report varied slightly in the presentation and type of information for a particular systematic review question, at minimum, the report included an evidence portfolio with a summary table of included studies. For some systematic review questions, additional information such as the search strategy and analytic framework were included. Excluded studies, with briefly stated reasons for exclusion, were also provided as either a complete reference list of excluded studies or the number of excluded studies.

Historically, the DGAC has also considered existing authoritative reports published by federal agencies or leading scientific organizations in its evidence review. For these questions, an evidence portfolio was not provided, because the conclusions were drawn directly from published reports. For example, several questions in the 2015 DGAC Scientific Report intended to address evidence on physical activity and health outcomes were based on conclusions from the Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Report, 2008, and associated publications (HHS/USDA, 2015b).

Findings

Use of existing systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and reports may be beneficial, considering the significant time and resources needed to conduct original systematic reviews. Using existing systematic reviews also serves to limit the duplication of efforts across groups conducting systematic reviews. However, inclusion of existing systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and reports depends on their quality and relevance in relation to the specific topic and question that is being considered. As is the case

for de novo systematic reviews, it is critical that the individual studies included in existing systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and reports are of high quality and adhere to standard methods.

Currently, the DGAC’s criteria note that systematic reviews must achieve an AMSTAR score of 8 or higher to be included; however, limitations to the AMSTAR tool have been identified (Burda et al., 2016; Faggion, 2015; Wegewitz et al., 2016), and this measure alone is not sufficient to determine the quality of a systematic review. As methods continue to advance, the DGAC criteria will need to adjust accordingly.

Within the DGAC’s stated criteria of inclusion, there are additional considerations, some of which are inherent to comparing reports, and others are specific challenges that may result in inabilities to use the existing systematic reviews as is. The assessment of published systematic reviews is based on reported information, which can vary widely across systematic reviews. A common challenge in using existing systematic reviews and relying on reported information is not having the necessary information to allow independent verification of the validity of the analyses and conclusions. Without the abilities to verify, the user of an existing systematic review has to trust the veracity of the reported information. Alternatively, the user may decide to use the existing systematic review as a framework and abstract only sufficient information from the original studies to carry out the necessary independent assessment.

Registration of the systematic review protocol on the PROSPERO website may provide additional information to assess whether the systematic review adhered to its original intent and methods. Archiving of data in websites such as the Systematic Review Data Repository provide opportunities for readers to assess the comprehensiveness and accuracy of the abstracted data used in systematic reviews. Although resources such as the Systematic Review Data Repository could increase transparency within the NEL process, their use is not required across organizations conducting systematic reviews, and many published systematic reviews may not have done so.

A more challenging problem occurs if disagreements in results and conclusions occur among multiple systematic reviews. The reason for discrepancy may sometimes be apparent, such as the obvious differences in the eligibility criteria or large differences in publication date and hence studies included. Discrepancies caused by subtle differences in the eligibility criteria or how such criteria were operationalized may be difficult to ascertain.

Missing data in the original systematic review may lead to an inability to include the systematic review, or the systematic review team may need to abstract additional information not reported by the original team that conducted the systematic review. It is difficult to know how the other

team operationalized eligibility criteria, even if the written criteria appear the same. Different methods used to assess the limitations of primary studies and grade the strength of evidence can also present challenges.

In some cases, the NEL staff, in determining inclusion of an existing systematic review, may be able to simply perform a new literature search to bring the existing review up to date, if they determined that the data abstraction and analyses performed by the original authors were accurate, and their interpretations were correct. In these cases, the NEL and DGAC would need to ensure data abstraction and interpretation were harmonized with the NEL protocol. Even if an existing systematic review is found not to be completely suitable because of the nature of the question(s) asked, the list of studies identified may still be helpful in conducting a new systematic review.

Conclusion

In summary, use of existing systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and authoritative reports from leading organizations is generally appropriate and encouraged by this National Academies committee, with the understanding that they ought to be relevant, timely, and of high quality. Efficiency and use of time and resources must be weighed carefully in using an existing systematic review compared to conducting a de novo review (Smith et al., 2011; Whitlock et al., 2008). However, opportunities exist to strengthen the current method of identifying existing systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and reports. Ongoing surveillance of the literature can serve to identify existing systematic reviews while maximizing resources. Surveillance can also help identify authoritative reports for use by the DGAC. There are also opportunities to leverage the Systematic Review Data Repository at AHRQ to further enhance the value and usefulness of the NEL to the nutrition research community. All systematic reviews and reports ought to meet the criteria for inclusion specified in the NEL protocol, with consideration for appropriate methods in cases of missing and unreported data.

EVALUATION OF METHODOLOGY AND USE OF FOOD PATTERN MODELING

Since the 1990 DGA Policy Report, specific food-intake guidance has been provided to help the public meet nutrient needs while moderating intake of other dietary constituents. Such guidance has been presented as a single food guide or multiple eating patterns (the USDA food patterns were substantially revised and formally described beginning in the 2005 DGAC Scientific Report), but the intention has remained the same: translate

nutritional recommendations into food intake recommendations that take account of the totality of the diet. In each instance, USDA has conducted food pattern modeling to derive this guidance for the DGAC.

Questions Food Pattern Modeling Is Intended to Address

Food pattern modeling, which assesses the nutrient content of various possible eating patterns based on typical choices within food groups, can be used to address a range of specific questions (see Appendix C). But the overarching question it seeks to answer is, “How well do varying combinations and amounts of food groups meet the Dietary Reference Intakes and potential recommendations in the DGA?” (Britten et al., 2006a,b). This is an important issue, given the myriad nutritional profiles of basic foods and the complex array of constraints involved in achieving nutritional adequacy while moderating consumption of energy and other dietary constituents. In effect, food pattern modeling shows how diets could be developed to meet those constraints. Three different patterns developed by USDA were featured in the 2015–2020 DGA Policy Report—“Healthy US-Style,” “Healthy Mediterranean-Style,” and “Healthy Vegetarian”—as “examples of healthy eating patterns that can be adapted based on cultural and personal preferences” (HHS/USDA, 2015a). The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) dietary pattern is also mentioned in the 2015–2020 DGA Policy Report as an “example of a healthy eating pattern . . . [with] . . . many of the same characteristics as the Healthy US-Style Eating Pattern” (HHS/USDA, 2015a). DASH was not derived via food pattern modeling; it was developed for a randomized controlled clinical trial to study the effect of that diet on cardiovascular risk factors.

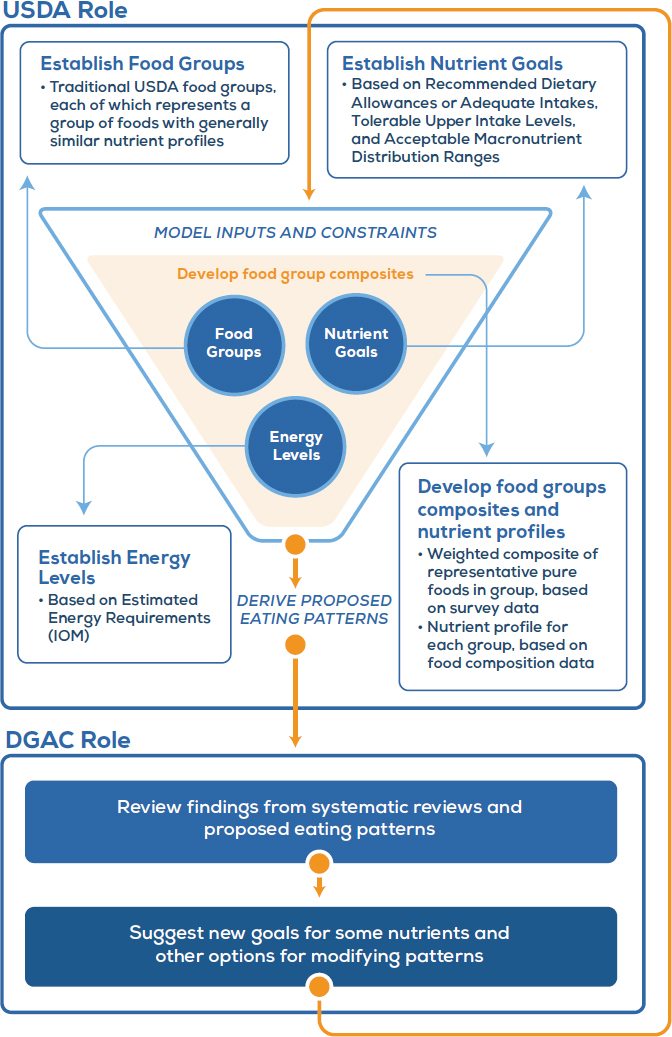

Current Methods Used to Derive Evidence: Steps in Process

Food pattern modeling that both informs and reflects the DGA recommendations has been an iterative process, at times developed concurrently with the DGA, with input from both the DGAC and federal staff (Britten et al., 2006a). For the 2015 DGAC, USDA staff from the Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion were designated by their leadership to work on food pattern modeling. They worked extensively with the DGAC in addressing possible modifications to the patterns through their support of DGAC committees. However, the DGAC and federal staff had unique roles in the process (see Figure 6-1).

The methods USDA employed to conduct the food pattern modeling required inherent assumptions in addressing the questions in Appendix C (Britten et al., 2006b). The first was that each specific question referred to the “total” rather than a “foundation” diet. Unlike other approaches to food

NOTES: The traditional USDA food groups are vegetables, fruits, grains, dairy, protein foods, oils, and calories for other uses. DGAC = Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee; IOM = Institute of Medicine; USDA = U.S. Department of Agriculture.