4

Strengthening Analyses and Advancing Methods Used

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA)1 must be based on the “preponderance of scientific and medical knowledge.”2 To achieve the goals of promoting health and reducing risk of chronic disease as proposed in Chapter 2, many types of inferential questions will need to be addressed, requiring that a wide range of information be considered to inform the DGA. To reach the most robust recommendations, the DGA also needs to be based on the highest standards of scientific evidence. Because scientific methods are continually evolving and new ones emerging, ensuring the scientific validity of the process to update the DGA will continue to depend on implementation of appropriate, validated, and standardized processes; adoption of strategic, efficient, and the most appropriate methods; and use of the most current high-quality data available. It will be critical to strengthen the data and analyses used in the DGA. Advancing the evidence underpinning the DGA will also require integrating newer methods that help better elucidate and represent the complex systems involved.

The DGA require the use of multiple sources of evidence. Data come from varying study designs, such as randomized trials and observational studies. These aggregate data, analyzed with the most current methodology, provide complementary information to answer different inferential questions and inform various parts of the evidence base. Properly evaluat-

___________________

1 Refer to Chapter 1, Box 1-1, for an explanation of how the term DGA is used throughout this National Academies report.

2 National Nutrition Monitoring and Related Research Act of 1990, Public Law 101-445, 101st Cong. (October 22, 1990), 7 U.S.C. 5341, 104 Stat. 1042–1044.

ing and calibrating results from a variety of data sources and methodological approaches are critical to understanding and interpreting the body of evidence to arrive at appropriate conclusions, as all study designs have innate limitations and can be susceptible to different types of bias. One key example is the complementary information derived from observational studies and randomized or controlled studies. If designed and conducted appropriately, randomized trials can control for confounders, allowing for causal relationships to be identified. Observational studies, because they do not use randomization to form comparison groups, can only establish association of effect and cannot be relied on to delineate mechanisms. However, given that many nutrition studies use observational designs and the populations and settings included more closely reflect the real world, these observational studies can provide other important insights that are complementary to the results of randomized trials. In addition, observational designs are employed when randomized trials cannot be conducted for reasons such as ethical concerns or logistical challenges. For instance, contextual information about the interface between foods and/or nutrients, as well as the interactions between diet and other factors can be derived from observational studies. Indeed, observational data have been used to provide important information in developing the DGA, such as data from surveys that inform findings related to disease prevalence and dietary intake patterns, among others. DGA recommendations will need to consider the results of multiple types of study designs.

The dual challenge faced in developing the DGAC Scientific Report, and subsequently the DGA Policy Report, is to properly assess the quality and interpret the results of studies available and to use them appropriately in drawing conclusions. The complexity of diet and health interactions necessitates the need for diverse types of analyses to inform strong and trustworthy conclusions. Taking the limitations of data and analyses into account in the collection, assessment, and decision-making process is crucial for building DGA that are based on the totality of scientific evidence and can be implemented.

This chapter first describes opportunities to strengthen the four types of analyses used by the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC): (1) original Nutrition Evidence Library (NEL) systematic reviews; (2) existing systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and reports in the literature; (3) food pattern modeling analyses; and (4) descriptive data analyses (see Chapter 6 for a full description and assessment of each analysis and additional information on the strengths and limitations of data sources). Improving these types of analyses will help describe the systems that connect dietary intake with health outcomes of interest. This chapter then offers opportunities to adopt strategic, appropriate, and efficient methods to advance the review of the evidence.

STRENGTHENING EXISTING ANALYSES

Significant efforts have been made to standardize methods used to inform the DGA and to present the analyses transparently. For example, the NEL was introduced in 2010, and standard inclusion criteria for existing systematic reviews and meta-analyses were developed in 2015. In the past, DGACs have reviewed, synthesized, and drawn conclusions regarding the body of evidence on select topics. The evidence review process traditionally has encompassed a collection of multiple complementary types of analyses, as necessitated by the different types of questions reviewed by the DGAC. The 2015 DGAC based its conclusions on understanding the relationships between diet and health or disease outcomes, food patterns, and evidence related to prevalence of disease (see Table 6-1 for examples3).

This National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies) committee envisions the work of the Dietary Guidelines Scientific Advisory Committee (DGSAC) to be focused on integrating results derived from multiple types of analyses (e.g., original systematic reviews; existing systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and reports; food pattern modeling; and descriptive data analyses) to develop conclusions about the totality of evidence relating diet and health (see Chapter 3 for additional details). One element of the process redesign model would be to create opportunities for analyses repeated in each DGA cycle to be prepared for review prior to the DGSAC’s first meeting. Having standardized analyses (e.g., prevalence of a specific disease) conducted outside of the DGSAC’s 2-year time frame of operation would allow the DGSAC to focus a greater proportion of its time synthesizing and interpreting the evidence and developing conclusions, as well as would facilitate comparisons between different cycles and over time. However, such analyses are contingent on the timing of the release of data from relevant surveys; availability of data may affect whether analyses can be completed before the DGSAC convenes. Approaches and methods that help better describe the systems and mechanisms involved also need to be used.

Systematic Reviews

This section describes opportunities to strengthen the conduct of NEL systematic reviews (de novo systematic reviews and updates) and the use of existing systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and reports.

___________________

3Table 6-1 includes three categories of questions (i.e., eating patterns, prevalence of disease, and relationships between diet and health) and provides examples from the 2015 DGAC Scientific Report, as well as links the category of question to the type of analysis conducted in the 2005, 2010, 2015 DGACs (e.g., prevalence of disease questions, the 2015 DGAC conducted descriptive data analyses).

Nutrition Evidence Library Original Systematic Reviews

The NEL conducted systematic reviews to address questions from the 2015 DGAC regarding the relationship between diet and health. While these important questions provided key inputs into the DGA, and will continue to do so, they are difficult to answer and require a strong body of evidence. The methods for conducting systematic reviews are crucial for developing trustworthy DGA. This National Academies committee assessed the NEL systematic review process, identifying several opportunities to advance and align the NEL protocol with existing best practices for systematic reviews.

As described in Chapter 6, the NEL original systematic review process to inform the 2010 and 2015 DGAC Scientific Reports has been facilitated by NEL staff, but staff relied heavily on input from the DGAC at each step to guide the process (see Box 4-1). However, standards for conducting systematic reviews and guidelines call for the clear delineation of roles in order to minimize the introduction of bias and allow for an objective, evidence-based review. Those who synthesize and interpret the evidence and formulate conclusions ought not to be leading the development of the systematic review protocol and selection of studies (e.g., inclusion/exclusion criteria) (AHRQ, 2014; Balshem et al., 2011; Guyatt et al., 2011). Drawing on the appropriate methodological and domain expertise in the systematic review process allows for robust outcomes while also maximizing time and resources for both NEL staff and outside expertise (e.g., a technical expert panel). As proposed in the process redesign model in Chapter 3, the NEL ought to focus on the following:

- Planning and conducting systematic reviews;

- Adhering to the specified protocol, including assisting in the development of systematic review questions;

- Conducting the literature search and screening and selecting articles;

- Abstracting data; and

- Conducting a risk of bias assessment4 in individual studies.

A technical expert panel (TEP) would provide supplemental domain and methodological expertise to the NEL at various steps as needed during the development of systematic reviews. The DGSAC’s role would be focused primarily on synthesizing the results of multiple systematic

___________________

4 A risk of bias assessment refers to evaluating the potential of bias in an individual study or collection of studies. Several published protocols are available for conducting a risk of bias assessment (AHRQ, 2014; Higgins and Green, 2011; IOM, 2011; Schünemann et al., 2013). The NEL process for conducting a risk of bias assessment is described in Chapter 6.

reviews and interpreting the body of evidence (see Box 4-2 for a description of terms). If needed, the NEL could assist the DGSAC in its synthesis of systematic review results given its familiarity with the primary studies. However, the interpretation of the body of evidence would be left solely to the DGSAC.

To be transparent, the NEL would need to make a number of its steps publicly available. These steps include the systematic review protocol, a rationale for each question being asked, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and reasons for why an article was or was not included in the review.

Additionally, an independent, external peer-review process for NEL systematic reviews will be critical to help increase the credibility of the systematic reviews. Peer review also provides opportunities to identify and correct any outstanding errors in the systematic review in advance of consideration by the DGSAC. To obtain an objective assessment, peer reviewers would ideally not have been involved with other steps of the process as members of the NEL or DGSAC. TEP members would only be involved as one of many peer reviewers, and not in a leading role. Although the NEL could facilitate the peer-review process, this National Academies committee suggests that the NEL explore existing infrastructures, such as collaborating with nutrition-focused scientific journals, to facilitate implementation of a peer-review process. This would reduce the need for the NEL to develop an infrastructure to support a peer review for individual systematic reviews. Collaborating with a peer-reviewed journal may also have the additional benefit of increasing the likelihood of publication of the systematic review. It would not be necessary for the systematic review to be published prior to consideration by the DGSAC due to time constraints. The NEL staff ought to consider publishing systematic reviews in peer-reviewed journals as appropriate. One example of this type of relationship is exemplified by collaborations that the Agency

for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Evidence-based Practice Centers Program has with peer-reviewed journals to conduct reviews and publish systematic reviews. All NEL systematic reviews should be peer reviewed to the extent possible. If time does not allow for the NEL to fully integrate peer-review comments into a revised systematic review, an alternative would be to share the original draft along with peer-review comments to the DGSAC for consideration as it synthesizes results and interprets the body of evidence.

Recommendation 3. The secretary of USDA should clearly separate the roles of USDA Nutrition Evidence Library (NEL) staff and the Dietary Guidelines Scientific Advisory Committee (DGSAC) such that

- The NEL staff plan and conduct systematic reviews with input from technical expert panels, perform risk of bias assessment of individual studies, and assist the DGSAC as needed.

- The NEL systematic reviews are externally peer reviewed prior to being made available for use by the DGSAC.

- The DGSAC synthesizes and interprets the results of systematic reviews and draws conclusions about the entire body of evidence.

Several best practices for systematic reviews have evolved and continue to be improved since the NEL systematic review protocol was developed. For the NEL to remain current and to continue to produce systematic reviews of the highest quality, this National Academies committee offers recommendations for the NEL to maintain state-of-the-art systematic review methods. Opportunities for collaboration and learning from other organizations should be leveraged, as well as training and support for NEL staff to actively engage in maintaining an up-to-date systematic review protocol. By instituting ongoing training and collaboration and supportive methodological infrastructure to cultivate systematic review practitioners with a nutrition focus, the NEL has the opportunity to become a leading evidence source for the nutrition community. Of note, some of the best practices identified by this National Academies committee—for example, the delineation of roles and the introduction of a TEP in developing systematic review questions—have already been integrated into the NEL process for conducting systematic reviews outside of the DGAC (see Chapter 6 for a description of the non-DGAC NEL process5). The systematic review pro-

___________________

5 The non-DGAC NEL process parallels the NEL process in many regards. The fundamental difference is that in the DGAC process, decisions are made by the DGAC with support

tocol used to conduct systematic reviews ought to reflect best practices to the extent feasible.

An explicit evaluation of how each step of the NEL protocol was implemented in previous DGA cycles was outside of this National Academies committee’s charge. However, critics have offered serious concerns that the implementation of the NEL protocol needs improvement (Heimowitz, 2016; Mozzaffarian, 2016; Trumbo, 2017; Willett, 2016). One possible improvement would be to invite systematic review experts to periodically assess the NEL process, as well as to learn from other leading organizations (e.g., AHRQ, Cochrane). Such relationships would be beneficial in particularly challenging steps of systematic reviews (e.g., implementation of grading criteria,6 evaluation of evidence). For example, AHRQ has several methods working groups that periodically review and update methods. While AHRQ and Cochrane have traditionally focused on conducting nonnutrition systematic reviews, there are enough overlaps in the process with nutrition systematic reviews that the NEL could benefit from participation in these forums. Furthermore, AHRQ and Cochrane at times also perform nutrition reviews, which could facilitate two-way collaboration between the NEL and other organizations.

Another opportunity for collaboration and alignment with best practices is in synthesizing and interpreting the body of evidence. These are subjective processes and require experience and expertise. As such, a standard and up-to-date approach is necessary to account for the strengths and the limitations of included studies, as well as to formulate evidence-based conclusions. In reviewing the current NEL process, this National Academies committee identified three opportunities for improvement:

- Use specific criteria/limit subjective criteria (e.g., explicit definition of a “large, high-quality, and/or consistent body of evidence”)

- Use quantitative confidence intervals (e.g., specific numeric confidence intervals in “high level of certainty”)

- Define explicit mechanisms for moving study grades up or down (e.g., explicit definition of “methodological or generalizability concerns”)

___________________

by the NEL in accordance with the Federal Advisory Committee Act. In contrast, in the non-DGAC NEL process, the NEL makes key decisions relating to systematic review methodology and relies on a technical expert collaborative for domain expertise. The non-DGAC NEL process also differs from the DGAC NEL process with respect to tools used for risk of bias assessment and evaluating the strength of a body of evidence.

6 Grading refers to evaluating a body of evidence in a systematic review. Several published protocols are available for evaluating a body of evidence according to specific criteria (AHRQ, 2014; Higgins and Green, 2011; IOM, 2011; Schünemann et al., 2013). The NEL criteria for grading are described in Chapter 6.

Conduct of original systematic reviews will need to be transparent and follow state-of-the-art methods, such as the GRADE approach and the AHRQ Evidence-based Practice Centers Program approach. However, this National Academies committee believes the NEL and DGSAC need to have the flexibility to align with appropriate standards or methods and does not recommend that any one standard be adopted, which may be subject to change and evolve over time. In assessing the overall evidence review process, this National Academies committee explored the options for conducting systematic reviews within the NEL, as well as options outside the NEL, such as contracting out a limited number of systematic reviews to be performed by external groups. However, there are advantages of a dedicated team conducting systematic reviews like the NEL, rather than contracting to outside groups. A dedicated in-house team has domain knowledge and institutional memories that can learn from past experiences. Compared with contracting with external sources, a dedicated team would likely be able to respond in a more nimble and timely manner to requests for systematic reviews.

Recommendation 4. The secretary of USDA should ensure all Nutrition Evidence Library (NEL) systematic reviews align with best practices by

- Enabling ongoing training of the NEL staff,

- Enabling engagement with and learning from external groups on the forefront of systematic review methods,

- Inviting external systematic review experts to periodically evaluate the NEL’s methods, and

- Investing in technological infrastructure.

Updating Systematic Reviews

In alignment with the need to increase adaptability and flexibility as outlined in Chapter 2, ongoing surveillance of the literature on any given topic is necessary to ensure that systematic reviews are up to date while maximizing use of resources. Determining when systematic reviews should be updated depends on a number of signals. In conducting a systematic review, the authors may assign the review a length of time for which the conclusions are expected to be relevant, or in other words, an “expiration date.” This may be determined based on the topic, known current research, expectations of future research, and the strength of the evidence, and ensures systematic reviews reflect the most current body of literature. After that time frame, to ensure conclusions remain relevant, reviews ought to be continually monitored and updated as needed based on new evidence or shifting priorities and questions. This National Acad-

emies committee envisions the ongoing surveillance and consideration for updating systematic reviews to be an activity of the NEL staff with input from the DGPCG.

Once a topic has been selected for the DGSAC to review, surveillance efforts ought to identify relevant existing systematic reviews. Upon identification, these existing systematic reviews would need to be evaluated for their timeliness and methodological quality. Updates may be needed, such as an updated search of the literature to identify possible new studies, a new search strategy to incorporate new questions, or additional analyses to be performed.

Updates of systematic reviews should be performed purposefully with the goal of answering a specific question. Revisions can be made on one’s own systematic reviews or those produced by others. Updating one’s own systematic reviews may be easier if all the data are standardized in their collection and archival. To ensure efficiency, data used in a previous systematic review will need to be readily available in a form that could be reused or could have new data elements added to it.

Existing Systematic Reviews

For the 2015 DGAC, efforts were made to use the existing literature to supplement or replace the need for an original review when a topic or question was reviewed that had already been addressed in existing systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and reports from leading organizations. The 2015 DGAC established a set of quality criteria that existing systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and reports needed to meet in order to be incorporated into the evidence base, including the relevance of the existing systematic review to the question of interest, the quality of the systematic review, the timeliness, and the reference overlap if multiple existing systematic reviews or meta-analyses were used for the same question (see Chapter 6 for a detailed description of how these criteria were implemented by the 2015 DGAC). No specific criteria were used by the NEL to evaluate existing reports.

Overall, this National Academies committee believes that using existing high-quality systematic reviews whenever possible maximizes limited time and resources and reduces duplication of efforts. However, it is important to recognize that existing systematic reviews may not use the same inclusion and exclusion criteria, may be out of date, or may have different outcomes (Smith et al., 2011; Whitlock et al., 2008). As a result, using existing systematic reviews may be more time and resource intensive than conducting de novo systematic reviews. The criteria upon which to evaluate the quality of existing systematic reviews currently outlined by the NEL have generally been appropriate for determining relevance

and inclusion or exclusion, but the criteria will need to be updated to keep pace with advances in systematic review methods, such as changes to AMSTAR and the Risk of Bias in Systematic Review tool (AMSTAR, 2016; Shea and Henry, 2016; Whiting et al., 2016).

Regardless of the type of systematic review being conducted or for whom (both NEL DGAC and non-DGAC systematic reviews), the NEL ought to follow a single set of standards, which needs to be transparent and of the highest quality. As systematic review methods evolve, the process to update the DGA will need to follow. For example, it is important to recognize that the quality, and thus the usefulness, of systematic reviews are dependent on the rigor of the original data. It will be up to the DGSAC and the DGPCG to determine how to develop conclusions based on low-quality data, as well as to identify areas where more research is needed to strengthen the evidence base. The NEL will need to adopt advances in systematic review methods to address the limitations related to low-quality data. Reproducibility is another methodological issue that will continue to be a problem in the future. Systematic review methods will continue to evolve and it will be important for the NEL and DGSAC to stay abreast of the literature in order to best adapt the methods used in the DGA process. Another example of an improvement in systematic review methods is the development of core outcome sets that could facilitate synthesis and comparison of systematic reviews, which could be part of the DGPCG strategic planning role (Clarke and Williamson, 2016; COMET Initiative, 2017). Additionally, systematic reviews have traditionally relied on summary results, or averages across all subjects in a study, reported in publications. With the advent of the requirement that trials be registered, the increase in patient registries, and the overall move toward open science, individual patient-level data will become more commonly available. Enhanced information can be extracted from individual patient-level data as compared to summary data. These improvements in systematic review methods will likely affect the analyses underlying the DGA.

Food Pattern Modeling

Food pattern modeling serves the important function of showing examples of ways individual diets can both meet energy (caloric) constraints and support intake of necessary nutrients at sufficient levels to promote health and prevent disease. The process to develop food patterns, as well as a number of important assumptions inherent in the process, is discussed in detail in Chapter 6. Box 4-3 lists the primary steps in food pattern modeling. Previous DGACs incorporated food pattern modeling in their reviews of the evidence, based on current food consumption

patterns and recommended nutrient intakes. In addition to translating nutrient requirements into food combinations, the models were also used to estimate how well various combinations of foods eaten on a daily or a weekly basis, called “eating patterns,” met Dietary Reference Intakes and recommendations in the DGA to promote health and prevent disease. Overall, this National Academies committee found food pattern modeling to be a useful exercise to elucidate relationships among food group nutrient profiles, nutrient goals, and energy constraints that helped inform decision making by the DGAC and the federal DGA writing team.

Diet constitutes an extremely complex system of exposure that is known to influence health, and these modeling exercises can help make sense of that complex system. Food pattern modeling has traditionally focused on representing the overall population through use of population average energy and nutrient requirements, typical food choices, and a traditional American diet set of food groups. However, the heterogeneity of the population is largely not accounted for, such as the distribution of requirements for energy and all nutrients, widely varying food choices by numerous demographic factors, and some food groups not being consumed by all Americans. Accordingly, food pattern models will be more useful as methods are strengthened to adapt to new areas of science, a better appreciation of the systems involved is formed, more systems science methods become available, and technology becomes increasingly more sophisticated. Food pattern modeling has employed set estimates for various inputs, a process known as deterministic modeling. Stochastic systems modeling, which more extensively and specifically accounts for variability and uncertainty, would be preferable, because making dietary recommendations as transparent, applicable, and robust as possible increases their ability to account for the complex systems involved and the variabilities in food composition and consumption. Simulation systems modeling is a type of stochastic modeling that could result in more real-life answers. Sensitivity analyses can then explore the effect of systematically varying different parameters.

A greater understanding of the variability in the estimates could readily be applied in two areas. The first is the range of nutrient values associated with each set of food group recommendations. All the nutrient profiles and the total nutrients associated with each pattern are dependent on the quality of the food composition data used to derive the estimates. For this purpose, USDA uses its own databases, which represent the nutrition field standard. However, it uses only the average composition values, rather than incorporating the information on variability surrounding the values that could enhance confidence in the adequacy of the patterns.

A second area where sensitivity analyses might be applied is in varying combinations of recommendations to achieve nutrient targets. This includes expansion of food patterns to show multiple ways to achieve targets. To some degree, the Mediterranean and vegetarian patterns reflect this concept, but further deviations from the American norm could be explored. For example, many Asian groups consume little to no dairy foods and use rice as a staple grain rather than wheat.

Because the complexity of the modeling may increase many fold with such adaptations, a stepwise approach toward additional layers of intricacy is warranted to see how each change affects the results. At the same time, development of system models can be facilitated by incorporating newer, more powerful, and more efficient computational techniques such as automated algorithms, rather than the current iterative approach that could become unwieldy, given the breadth of foods to be considered as inputs into the models. As nutritional recommendations are likely to become more personalized in the future, the adjustments to food pattern modeling will need to follow suit. For example, appropriate energy intake levels might be tailored according to whether a person is at, over, or below ideal weight, and food intolerances such as allergies could be accounted for in building patterns. As with any modeling, it will be important to include an evaluation of the certainty regarding the input parameters in future approaches.

Even using the relatively limited deterministic approach, food pattern modeling reveals the very small allowance for discretionary calories relative to population intakes of energy from added sugars, solid fats, and alcohol. This revelation is critically important, and yet understanding by the public of how the resulting patterns should be interpreted and followed seems to be lacking, as evidenced by the discordance between recommendations and usual intakes (Krebs-Smith et al., 2010; NCI, 2015). Furthermore, the national food supply is not consistent with these patterns; for example, the mix of foods entering retail distribution channels does not represent the balance among fruits, vegetables, whole grains, dairy, protein foods, and empty calories as recommended by federal

guidance (Miller et al., 2015). Results and implications of food pattern modeling exercises should be evaluated for how well they are implemented across the food supply chain.

In summary, this National Academies committee determined that food pattern modeling, as currently conducted, answers an important but narrow set of questions with appropriate methodologies. However, more key questions involving different assumptions could be addressed with a more expansive use of modeling and system science. Advancing the methods used in food pattern modeling to account for the complex systems and associated pathways and variability in American diets would strengthen the accuracy of outcomes and better account for the variability in food patterns and their resulting impact to support health and prevent disease. These advancements would offer important insights into the range of nutrients and the varying combinations of “allowable” foods to stay within dietary guidelines, providing flexibility in food and taste preferences, cultural norms, and other individual factors. In addition, complex systems models more accurately represent the dynamic nature of food and eating patterns, and they can be adapted to changing diets and population needs over time, as well as reflect future advancements in methods. It will also be critical for researchers to translate findings from these models for the general population.

Recommendation 5. The secretaries of USDA and HHS should enhance food pattern modeling to better reflect the complex interactions involved, variability in intakes, and range of possible healthful diets.

Descriptive Data Analyses

Descriptive data analyses provide key insights to understanding the context and landscape of dietary patterns and population health and disease, including both current intakes and prevalence of disease. Data analyses to inform the 2015 DGAC’s review of the evidence constituted examinations of primary data sources to answer descriptive questions about the overall population and population subgroups, such as “What are current consumption patterns of nutrients from foods and beverages by the U.S. population?” (for a full list of questions, see Appendix C). For dietary intakes, the DGAC relied primarily on the dietary portion of What We Eat in America (WWEIA) of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), which uses self-reported dietary intake data through the 24-hour dietary recall method. The 2015 DGAC also used other selected data sources (see Table 6-5 for a summary of data sources used in the Scientific Report of the 2015

DGAC).7 In the past, the data analyses were initiated concurrently with the convening of the DGAC. However, data analyses could be made more efficient by identifying questions earlier and having available data sooner, allowing for select data analyses to be performed before the first meeting of the DGSAC. In most instances, the data sources and analyses used by the 2015 DGAC addressed the questions it posed. It would be helpful for data analyses to be standardized to the extent possible to allow for direct comparisons of results over time. This National Academies committee also found that the availability of data can limit the scope of the data analyses, and the expansion of data collection efforts and advancement of methods could lead to improvements in the understanding of population health and disease prevalence and trends, particularly for population subgroups.

One area that would be particularly important to standardize, both within and across DGSAC cycles, is identification of nutrients of concern—an evaluation of the prevalence of nutrient inadequacies and excesses in the U.S. population and select population groups and associated health implications (see Chapter 7 for additional discussion). Identification of nutrients of concern would allow the DGSAC to focus on select nutrients that, if either increased or decreased compared to current intake levels, could affect population health. Nutrients of concern also can drive subsequent implementation and education efforts, and they have also been used as food sector reformulations to vary nutrient levels in products. The analytic approach to determining the proportion of the population with inadequate intakes or at risk of adverse effects owing to excess consumption has been relatively comparable across the past three editions of the DGAC Scientific Report. However, the interpretation and application of those quantitative assessments has differed across the various cycles. Differences include the thresholds used to define a nutrient as being of concern, and the degree to which biochemical and chronic disease-related data were available and used to justify the designation (see Chapter 7 for additional details). As validated biomarkers that are surrogate end points of chronic disease become available, it will be important to understand how biomarker research can be included into the DGA evidence review process.

An adoption of a more consistent approach to designating nutrients of concern in a DGAC conclusion would benefit practitioners, consumers, and the food sector. Such an approach would standardize the quantita-

___________________

7 Other data sources used for information on health conditions and trends and disease prevalence were the American Heart Association statistics, the National Health Interview Survey, the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth study, and the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. The USDA-ARS National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 27 was used for food composition data.

tive threshold of inadequacy or excess and the integration of other supporting evidence to identify a nutrient of concern. As described in the process redesign model in Chapter 3, development of data inputs ought to be independent from the DGSAC, similar to the delineated roles of the DGSAC and the NEL for systematic reviews.

Recommendation 6. The secretaries of USDA and HHS should standardize the methods and criteria for establishing nutrients of concern.

A standard approach to identifying diet-related chronic disease for inclusion in the DGA would also be helpful. Knowing which chronic diseases are affected by diet, as well as what diets have been linked with decreasing or increasing risk of development of chronic disease, are integral to producing guidelines that can reduce the risk of chronic disease. However, the science to explain these relationships needs further research in order to establish the mechanisms underlying diet and health.

To conclude, descriptive data analyses can be useful in guiding the conclusions of the DGSAC. Common analyses can be performed in each cycle to inform key decisions. Consistent use of standardized approaches to descriptive data analyses, including prevalence in the population beyond which a nutrient is considered of concern, would facilitate comparisons between different cycles and over time. Descriptive data analyses could also benefit from peer review if applicable. Although flexibility can allow for adaptations and responses to changes for areas in which evidence and methodologies are rapidly emerging, applying a standardized approach across DGA cycles would allow for a more direct comparison of evidence across reports. It would be valuable, as a first step, to document all the descriptive data analyses commonly used across previous DGACs.

Quality of Dietary Data Across All Evidence Types

It is important that the data informing the DGSAC Scientific Report are generated using validated and appropriate methods. The analysis and interpretation of the data also need to be consistent with best practices. Box 4-4 discusses several resources for improving the quality of self-reported dietary intake data.8 In addition to providing a transparent con-

___________________

8 Self-report dietary intake data are central to the development of dietary guidelines. Measurement error is a substantial limitation of self-report dietary intake data, and can lead to various degrees of bias based on the method of collecting self-report dietary intake data (NCI, 2017). Several methods exist to address the effects of measurement error. See Chapter 6 for an explanation of the types of measurement error and implications for appropriate use of self-report dietary intake data.

sideration of the quality of food intake data, future data analyses could be made more efficient by identifying questions earlier and having available data sooner, allowing for select data analyses to be performed before the first meeting of the DGSAC. It would also be helpful for selection of data and data analyses to be standardized using best practices to the extent possible to allow for direct comparisons of results over time.

ADVANCING METHODS USED

The types of questions asked by recent DGACs have been limited by the available evidence, data, and methods. Strengthening the data available and the statistical and epidemiologic analyses conducted will enhance important insights regarding factors in the diet–health relationship. These approaches, however, are not designed to understand how strings of actions, reactions, and new actions among multiple health-relevant sectors and diet may affect an overall system outcome such as weight and chronic disease occurrence. These insights are the domain of complex systems science with methods such as systems dynamics, agent-based modeling, and network modeling (El-Sayed and Galea, 2017; Sterman, 2006). Incorporating systems science approaches to data and evidence assessment in the DGA process can extend the value provided by better data and traditional analytical methods.

Developments in knowledge and data, as well as computing systems and computational methods and capabilities, now present opportunities to approach relationships in diet and health with an appreciation for the complexity that exists in the real world. As discussed in Chapter 2, this National Academies committee believes that adding complex systems approaches to current analytical approaches can advance the understand-

ing of complex interrelated factors at play in both population and individual health. Systems approaches have been used successfully in addressing many public health challenges (see Box 4-5 for examples).

Specific examples of systems mapping and modeling linking nutrition and health are limited (Lee et al., 2017b). Integrating systems approaches into the field of nutrition will require the same bold experimentation with systems science methods that was undertaken in other domains when no evidence of its value for their specific application existed. This is a cultural shift. Currently, nutrition research, and thus the DGA process, begins with the available data and looks for trends in those data. The cultural shift would involve researchers beginning with a systems map and model, which represent the relationships and potential mechanisms involved, and then using the model to help prioritize and guide the collection and analysis of data. Developing and enhancing the maps and models is an essential and iterative process.

Previous DGACs have recognized the potential value and discussed the need to move toward use of systems approaches. The 2015 DGAC integrated a theoretical model that accounted for the multidimensional relationship and multiple factors influencing both dietary intake and health (see Figure 7-1 for the 2015 DGAC conceptual map). It is now time to translate this theoretical systems discussion into an actual application to the DGA process, including building systems maps and integrating systems models as an expanded analytic framework for the evidence review. Systems thinking, when fully integrated into the DGA process and supported with systems mapping and modeling, has the potential to influence the DGA recommendations based on an expanded knowledge of the diet–health relationships of interest, inform the translation of the guidelines to maximize impact, and identify relevant connections across stakeholders. Systems maps, by highlighting areas of stronger and weaker evidence, can also help to prioritize subsequent research and data collection needs. Within the DGA process, there would be a dynamic, interdependent relationship between the systems maps, models, data, questions of interest, and recommendations for the DGA and future directions. For example, building a systems map could inform key topic and question development. The DGSAC’s review of the evidence could provide data inputs in the development of a systems model. Additionally, the outputs of the systems maps and models could provide important inputs into the DGA.

It is important to understand the range of different types of modeling approaches and how they differ in their strengths and weaknesses and ability to represent the interactions and mechanisms involved. On one end of the spectrum are “deterministic” statistical modeling and epidemiological approaches that take existing datasets and help identify associations and trends and make predictions, but do not necessarily elu-

cidate and represent the actual mechanisms involved. Examples include traditional epidemiological studies that can reveal patterns and associations and attempt to control for confounding factors, such as selection and observation biases. Randomized or controlled trials may be able to answer specific efficacy questions but occur in a nonreal-world, controlled setting and thus do not represent all or even most of the interactions and mechanisms that are operative in the real world (i.e., a given complex

system). By contrast, systems modeling is essentially a “nondeterministic” approach that attempts to simulate real-world heterogeneity and the relationships and array of mechanisms that affect the relationship between diet and health. By trying to build a representation of a system, the system overall can be better understood, as well as the dependencies and potential effects of the various system components on a given outcome or risk.

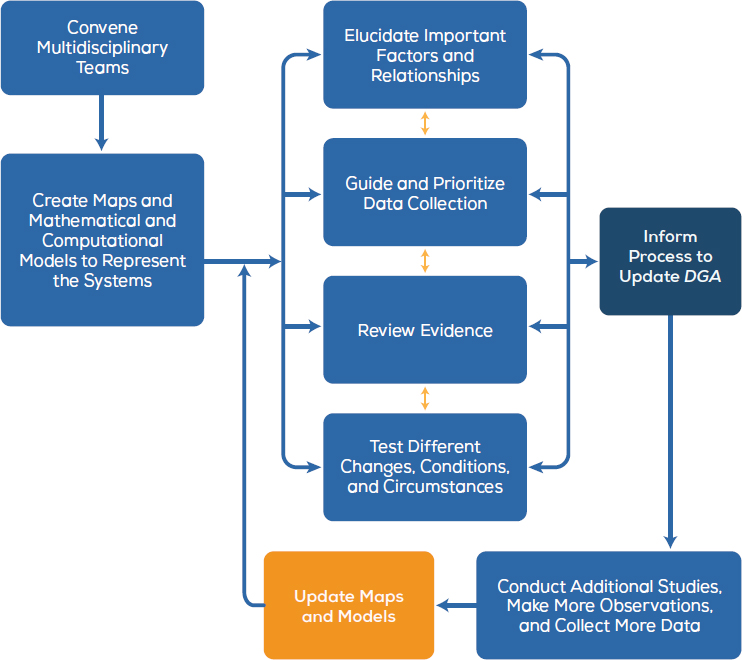

Figure 4-1 shows that implementation of systems approaches for the

NOTE: The orange box indicates the cyclical and iterative nature of the systems approach; the dark blue box feeds into the process to update the DGA.

DGA involves an organized, iterative process in which an initial systems map is generated, which in turn serves as a blueprint for the systems models. It then guides data collection and study design and implementation, generating more data to further augment and refine the systems maps and models. As Figure 4-1 demonstrates, because the systems involved are complex, fully comprehending these systems will take time over multiple cycles of the DGA. An initial representation or model of a system will help guide subsequent scientific exploration and data collection, which in turn can further develop the model.

It may require a few years for systems approaches to be optimally incorporated into the DGA process. Although full acceptance, understanding, and integration of systems science will require a sustained, long-term effort, some steps can be taken immediately. Relevant data need to be assembled and catalogued, and modelers with appropriate experience and expertise assembled. Initial systems maps and models will also

need to be identified, assembled, or developed. A systems map needs to be created that represents how diet affects health and disease across the variability seen throughout the American population. The systems map will drive the development of the systems models and can then help guide and prioritize data collection. The models will allow for different scenarios to be run (e.g., varying nutritional intakes) to determine what the effects would be. An important, ongoing concurrent process is continuing validation of the models. Typically, validation activities fall into three general types: (1) face validity, (2) criterion validity, and (3) convergence/divergence validity.9 Sensitivity analyses (systematically varying the values of different parameters) also need to be conducted to help understand the effect of assumptions, uncertainty, and variability in input parameters and the robustness of any results and conclusions.

One hypothetical example of how systems science could be used in nutrition is the relationship between saturated fat and coronary artery disease. Research has suggested that excessive saturated fat intake can lead to lipid deposition within blood vessel walls, initiating a cascade of inflammatory and immune reactions resulting in coronary artery disease. However, there are multiple intermediate steps and potential modifying factors. For example, once ingested, the dietary fat is absorbed through the gastrointestinal tract to varying degrees, which may be affected by local mechanisms and genetic factors. Once in the blood stream, the fat may be further metabolized by the liver in ways that can vary depending on the individual’s metabolism, liver function, and genetic predisposition. Further pathways affect how the fat may be transported to the coronary arteries and ultimately deposited. There are also different ways in which blockage of coronary arteries may result in cardiac events. These pathways also do not account for all of the factors and mechanisms outside the body that can modify the way dietary fat affects heart disease (see Box 4-5). Therefore, to fully understand the relationship between fat and coronary artery disease, these pathways need to be outlined in a systems map. Then, mathematical equations need to be developed to represent the dynamics of each of these pathways, including the factors that affect them. Once the initial model is in place, the levels of dietary fat intake can be varied to determine effects throughout the pathways and the result on cardiac outcomes. The process of constructing the systems map and model, as well as running the model, can also help identify knowledge

___________________

9 Face validity involves showing a model to different experts to determine whether the model represents what it is intended to represent. Criterion validation refers to how well a model can recreate retrospective, concurrent, or prospective data. Convergence/divergence validation compares a model with other modes (e.g., other models, calculations).

and data gaps. Sensitivity analyses can show the effect of each knowledge gap and thus help prioritize future data collection and studies.

This National Academies committee recognizes that the integration of systems science into the field of nutrition is still early, but it believes more aggressive efforts to deploy and evaluate this science should begin now. While arguments have been made that the integration of systems science needs to wait until more data are available and more research has been conducted, the act of beginning to develop systems maps and models can help identify the types of data that need to be collected and the value of collecting such data. These efforts can begin, even with imperfect data.

Recommendation 7. The secretaries of USDA and HHS should commission research and evaluate strategies to develop and implement systems approaches into the DGA. The selected strategies should then begin to be used to integrate systems mapping and modeling into the DGA process.

This National Academies committee envisions the nutrition systems mapping and modeling endeavor to be an ongoing process, as described above, either built into an agency or outsourced to an organization with a proven track record in systems approaches. Recognizing that the development and implementation of systems approaches will be gradual, iterative, and occur over a number of years, the foundation for the process will ideally begin with the 2020–2025 DGA cycle. To initiate the process, the secretaries of USDA and HHS ought to consider convening a group of experts to develop a strategy for the implementation of systems approaches and systems mapping and modeling in the DGA. This National Academies committee envisions a workshop, which includes relevant federal and nonfederal expertise, to discuss the options for integrating systems approaches into the DGA and result in strategic short- and long-term plans.

CONCLUSION

The DGA are based on the DGAC’s conclusions, drawn from the integration of multiple types of analyses. Ensuring that the appropriate conclusions are reached requires that the most current and highest-quality data are used, and that appropriate, validated, and standardized methods are implemented.

Current methods need to be strengthened to better support the development of credible and trustworthy DGA. Strengthening the NEL process for conducting systematic reviews will require a multipronged approach. First, clearly delineating the roles of the DGSAC and the NEL staff, as

well as incorporating formal peer review, would ensure that appropriate methods are used and would minimize the risk of bias in conducting systematic reviews. Second, enhancing the quality of NEL systematic reviews would necessitate alignment with current best practices. For example, ongoing collaboration with other organizations and training of NEL staff, combined with the technological infrastructure to support new systematic review methods, will need to be supported. The usefulness of food pattern modeling analyses can also be enhanced by accounting for complexity and variability in diets. Similarly, descriptive data analyses that provide valuable information to evaluate diet and health outcomes at the individual and population levels can be improved with the use of methods to standardize and improve data quality. In addition, standardizing approaches across DGA cycles, in particular approaches to designating nutrients of concern, would allow for comparisons to be made over time.

Advancing the science underlying the DGA requires that new methods be adopted as they become available. The relationship between diet and health is complex and exists within larger and more complex systems. As such, efforts to integrate systems approaches and methods (such as mapping and modeling) into the framework for evidence review would result in a better understanding of the mechanisms involving diet and particular health outcomes.

REFERENCES

AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality). 2014. Methods guide for effectiveness and comparative effectiveness reviews. AHRQ Publication No. 10(14)-EHC063-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. http://www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov (accessed May 31, 2017).

AMSTAR (A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews). 2015. What is AMSTAR? https://amstar.ca/About_Amstar.php (accessed August 14, 2017).

Balshem, H., M. Helfand, H. J. Schünemann, A. D. Oxman, R. Kunz, J. Brožek, G. E. Vist, Y. Falck-Ytter, J. Meerpohl, S. Norris, and G. H. Guyatt. 2011. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 64(4):401-406.

Clarke, M., and P. R. Williamson. 2016. Core outcome sets and systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews 5(1):11.

COMET Initiative. 2017. Core outcome measures in effectiveness trials initiative. http://www.comet-initiative.org (accessed June 23, 2017).

Dhurandhar, N. V., D. Schoeller, A. W. Brown, S. B. Heymsfield, D. Thomas, T. I. Sorensen, J. R. Speakman, M. Jeansonne, and D. B. Allison. 2015. Energy balance measurement: When something is not better than nothing. International Journal of Obesity (London) 39(7):1109-1113.

El-Sayed, A. M., and S. Galea. 2017. Systems science and population health: Oxford Scholarship Online. https://global.oup.com/academic/product/systems-science-and-populationhealth-9780190492397?cc=us&lang=en& (accessed August 13, 2017).

Guyatt, G. H., A. D. Oxman, R. Kunz, D. Atkins, J. Brožek, G. Vist, P. Alderson, P. Glasziou, Y. Falck-Ytter, and H. J. Schünemann. 2011. GRADE guidelines: 2. Framing the question and deciding on important outcomes. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 64(4):395-400.

Heimowitz, C. 2016 (unpublished). Comments presented at USDA Dietary Guidelines for Americans listening sessions: Atkins Nutritionals. Washington, DC, February 19, 2016.

Higgins, J., and S. Green, editors. 2011. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, version 5.1.0, The Cochrane Collaboration. http://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org (accessed August 3, 2017).

Homer, J., B. Milstein, K. Wile, P. Pratibhu, R. Farris, and D. Orenstein. 2008. Modeling the local dynamics of cardiovascular health: Risk factors, context, and capacity. Preventing Chronic Disease 5(2):A63-A69.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2011. Finding what works in health care: Standards for systematic reviews. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Krebs-Smith, S. M., P. M. Guenther, A. F. Subar, S. I. Kirkpatrick, and K. W. Dodd. 2010. Americans do not meet federal dietary recommendations. Journal of Nutrition 140(10):1832-1838.

Lachat, C., D. Hawwash, M. C. Ocké, C. Berg, E. Forsum, A. Hörnell, C. Larsson, E. Sonestedt, E. Wirfält, A. Åkesson, P. Kolsteren, G. Byrnes, W. De Keyzer, J. Van Camp, J. E. Cade, N. Slimani, M. Cevallos, M. Egger, and I. Huybrechts. 2016. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology—nutritional epidemiology (STROBE-nut): An extension of the STROBE statement. PLOS Medicine 13(6):e1002036.

Lee, B. Y., A. Adam, E. Zenkov, D. Hertenstein, M. C. Ferguson, P. I. Wang, M. S. Wong, P. Wedlock, S. Nyathi, J. Gittelsohn, S. Falah-Fini, S. M. Bartsch, L. J. Cheskin, and S. T. Brown. 2017a. Modeling the economic and health impact of increasing children’s physical activity in the United States. Health Affairs 36(5):902-908.

Lee, B. Y., S. M. Bartsch, Y. Mui, L. A. Haidari, M. L. Spiker, and J. Gittelsohn. 2017b. A systems approach to obesity. Nutrition Reviews 75(Suppl 1):94-106.

Miller, P. E., J. Reedy, S. I. Kirkpatrick, and S. M. Krebs-Smith. 2015. The United States food supply is not consistent with dietary guidance: Evidence from an evaluation using the Healthy Eating Index-2010. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 115(1):95-100.

Mozzaffarian, D. 2016 (unpublished). Comments presented at USDA Dietary Guidelines for Americans listening sessions. Washington, DC, February 19, 2016.

NCI (National Cancer Institute). 2015. Usual dietary intakes: Food intakes of U.S. population, 2007–2010. Epidemiology and Genomics Research Program, National Cancer Institute. https://epi.grants.cancer.gov/diet/usualintakes/pop/2007-10 (accessed May 20, 2017).

NCI. 2017. Dietary assessment primer. https://dietassessmentprimer.cancer.gov (accessed June 9, 2017).

Schünemann, H., J. Brožek, G. Guyatt, and A. Oxman, editors. 2013. Handbook for grading the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations using the GRADE approach. The GRADE Working Group. http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/app/handbook/handbook.html#h.33qgws879zw (accessed August 3, 2017).

Shea, B., and D. Henry. 2016. Development of AMSTAR 2. In: Challenges to evidence-based health care and Cochrane. Abstracts of the 24th Cochrane Colloquium, 23-27 October, 2016, Seoul, South Korea. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Smith, V., D. Devane, C. M. Begley, and M. Clarke. 2011. Methodology in conducting a systematic review of systematic reviews of healthcare interventions. BMC Medical Research Methodology 11(1):15.

Sterman, J. D. 2006. Learning from evidence in a complex world. American Journal of Public Health 96(3):505-514.

Subar, A. F., L. S. Freedman, J. A. Tooze, S. I. Kirkpatrick, C. Boushey, M. L. Neuhouser, F. E. Thompson, N. Potischman, P. M. Guenther, V. Tarasuk, J. Reedy, and S. M. Krebs-Smith. 2015. Addressing current criticism regarding the value of self-report dietary data. Journal of Nutrition 145(12):2639-2645.

Trumbo, P. 2017 (unpublished). Comments to the committee to review the process to update the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Washington, DC, January 29, 2017.

USDA (U.S. Department of Agriculture)/HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2016 (unpublished). Dietary Guidelines for Americans: Process brief, sections 4–5. Prepared for the Committee to Review the Process to Update the Dietary Guidelines for Americans.

Whiting, P., J. Savovi, J. P. T. Higgins, D. M. Caldwell, B. C. Reeves, B. Shea, P. Davies, J. Kleijnen, and R. Churchill. 2016. ROBIS: A new tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews was developed. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 69:225-234.

Whitlock, E. P., J. S. Lin, R. Chou, P. Shekelle, and K. A. Robinson. 2008. Using existing systematic reviews in complex systematic reviews. Annals of Internal Medicine 148(10):776-782.

Willett, W. 2016 (unpublished). Comments presented at USDA Dietary Guidelines for Americans listening sessions. Washington, DC, February 19, 2016.

This page intentionally left blank.