1

Introduction

The organ donation and transplantation system strives to honor the gift of donated organs by fully using those organs to save or improve the quality of the lives of transplant recipients. As a result of advances achieved through basic and clinical research over the past several decades, organ transplantation has become the optimal treatment for many end-stage organ-specific diseases. However, there are not enough donated organs to meet the demand. Furthermore, some organs may not be recovered, some recovered organs may not be transplanted, and some transplanted organs may not function adequately, all of which exacerbates the imbalance between the supply and the demand of organs. A determination that an organ is not suitable for transplantation is based on a variety of factors, such as the health of the deceased donor, the cause of death, or functional or anatomic abnormalities found in a potential donor or donor organ. To date, organ transplantation research has focused almost exclusively on transplant recipients and on finding ways to improve transplantation processes and post-transplant health outcomes. Improvements that increase the number and improve the quality of organs that are available for transplantation have been slow to come, with most of them having been developed through innovations in local practice standards. Conducting research in deceased organ donors and on organs that have been recovered from deceased donors has emerged as one means to identify new methods to improve the quality and increase the quantity of organs that can be successfully transplanted and thus, hopefully, expand the number of people receiving an adequately functioning organ.

Achieving advances in the quality and quantity of organs that can be recovered from deceased donors and successfully transplanted will require organ donor intervention research that tests and assesses clinical interventions (e.g., medications, devices, donor management protocols) that are aimed at maintaining or improving organ quality prior to, during, and following transplantation. In this type of research, the intervention is administered either while the organ is still in the deceased donor or after it is recovered from the donor but before it is transplanted into a recipient. Organ donor intervention research protocols often assess the outcomes of the intervention through follow-up of the transplant recipient. As discussed throughout this report, organ donor intervention research requires extensive oversight and careful planning to ensure that the integrity of the donation and transplantation process is maintained and that fully using the gift of the donated organ has the highest priority in all phases of this research.

Deceased organ donor intervention research has the potential to help address the growing need for organs and increase the likelihood of positive health outcomes following transplantation by identifying interventions to maintain or improve organ quality prior to, during, and following transplantation. Conducting organ donor intervention research presents new challenges to the organ donation and transplantation community by raising ethical questions about who should be considered a human subject in a research study, whose permission and oversight are needed, and how to ensure that the research does not threaten the equitable distribution of a scarce and valuable resource. Furthermore, when a research intervention is administered to a deceased donor prior to organ recovery and the intent is to have an effect on a specific organ such as a kidney (i.e., the target organ), the intervention could affect other organs that will also be transplanted afterward (i.e., non-target organs). This report provides recommendations for how to conduct this research in a manner that maintains high ethical standards, ensures dignity and respect for deceased organ donors and their families, provides transparency and information for transplant candidates who might receive an organ that has been involved in donor intervention research, and supports and sustains the public’s trust in organ donation and transplantation.

THE POTENTIAL OF ORGAN DONOR INTERVENTION RESEARCH

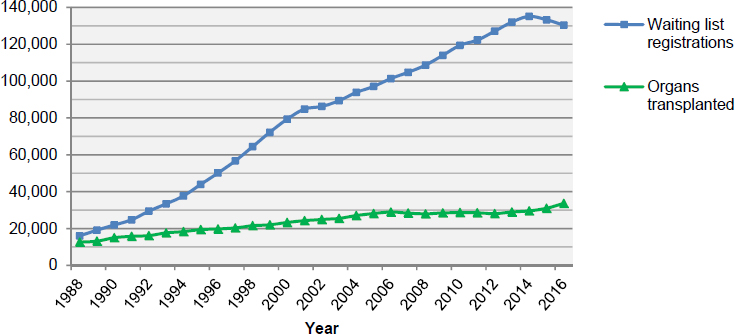

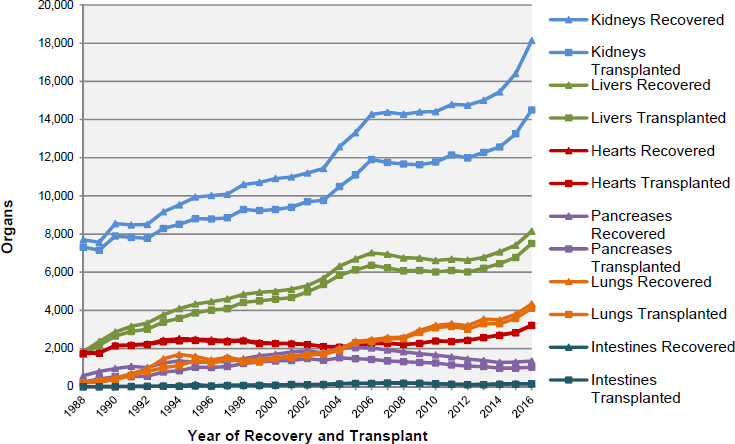

In 2016, approximately 82 percent of the organs transplanted in the United States were from deceased donors—27,630 organs were transplanted from 9,971 deceased individuals, while an additional 5,980 organs were transplanted from living donors (OPTN, 2017f). The number of organs transplanted has increased in recent decades; for example, in 1988

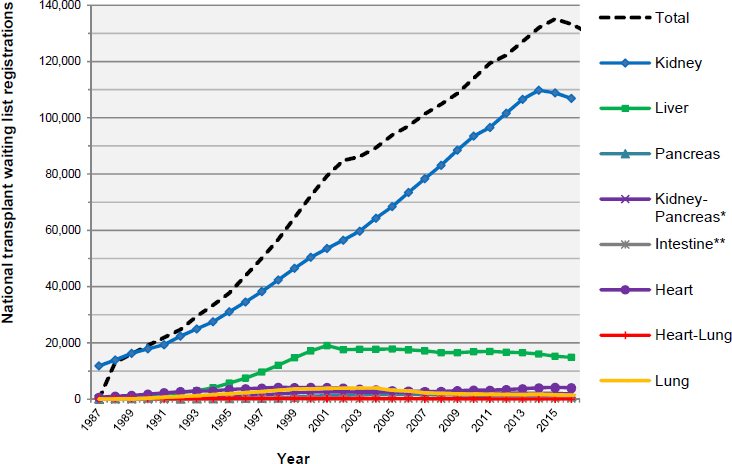

only 10,794 organs were transplanted from deceased donors, with an additional 1,829 organs transplanted from living donors (OPTN, 2017f). The outcomes for transplant recipients, including graft survival, have also improved (Hart et al., 2017; Kandaswamy et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2017; Smith et al., 2017). However, the growth in the number of patients awaiting an organ transplant has far outpaced the growth in the number of organs being transplanted (see Figure 1-1). As of July 13, 2017, 117,154 candidates were on the waiting list (see Table 1-1 for the number of specific organs needed by waiting list candidates and Figure 1-2 for waiting list registrations over time). This demand far outweighs the supply. Waiting list figures underestimate true need because there are many more who could benefit from organ transplantation, but whose condition is not yet severe enough to meet the requirements for candidature on the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network/United Network for Organ Sharing (OPTN/UNOS) waiting list or for other reasons are not on the list (Patzer et al., 2015; Goldberg et al., 2016). The supply of organs available for transplantation is affected by a number of factors, including the public’s willingness to donate organs, the number of potential organ donors, the health of a given donor, the condition and likelihood of adequate function of an organ once it is recovered from a donor, and the ability of an organ procurement organization (OPO) working with OPTN/UNOS to allocate a donor organ to a recipient within the timeframe that the organ is viable for transplantation. Every year many donor organs go to waste because they are considered to be at risk of functioning poorly or not at all if they were to be transplanted. Similarly, concerns about a donor’s medical and

SOURCES: Data from Eidbo, 2017; OPTN, 2017f.

TABLE 1-1

Waiting List Candidates by Organ Type as of July 13, 2017

| Organ | Number of Waiting List Candidates |

|---|---|

| Total | 117,154 |

| Kidney | 97,116 |

| Liver | 14,274 |

| Heart | 3,933 |

| Kidney and Pancreas | 1,708 |

| Lung | 1,352 |

| Pancreas | 905 |

| Intestine | 262 |

| Heart and Lung | 38 |

SOURCE: OPTN, 2017f.

NOTES: Some candidates are wait listed with more than one transplant center, and therefore the number of registrations may be greater than the number of candidates. Waiting list totals are from December 31 each year from 1987 through 2016.

*A separate kidney-pancreas waiting list within the national transplant list was created in 1992.

**A separate intestine waiting list within the national transplant waiting list was created in July 1993.

SOURCE: Data from Eidbo, 2017.

physiological conditions prevent many potential donors from becoming actual organ donors.

Organ donor intervention research examines the interventions that are administered to a donor or to a donor’s organs after death and after the authorization for donation has been granted by either the deceased donor (prior to death) or a surrogate. The intent of the research is to test interventions that are hoped to increase the likelihood of an organ being viable for transplantation and find ways to optimize graft function in organs that are transplanted into candidates.1 For example, the quality of organs for transplantation might be improved with certain treatments carried out prior to organ recovery that transform organs that previously would not have been healthy enough for transplantation into organs that now are sufficiently healthy. Additionally, methods might be discovered that could increase the length of time that an organ is viable after recovery and before transplantation or that could reduce the time it takes until an organ reaches full or adequate function after transplantation. Examples of interventions that have been examined to date include hypothermia and varying perfusion solutions and processes (detailed in Chapter 3). The organs involved in this type of research are not used solely for research purposes—transplantation of the organ follows the research intervention. Thus, deceased organ donor intervention research has a dual purpose—furthering knowledge to improve outcomes and transplanting organs. However, deceased organ donor intervention research has not been extensively conducted to date because of the combination of the legal, regulatory, and ethical complexities associated with conducting this research and the inherent logistical complications that arise from the organ donation and transplantation process (Feng, 2010; Abt et al., 2013; Glazier et al., 2015; Heffernan and Glazier, 2017)—a process that requires decisions to be made in a short period of time by stakeholders (OPTN, 2017i).

STUDY BACKGROUND AND SCOPE

This report examines the ethical, legal, regulatory, policy, and organizational issues relevant to the conduct of research involving deceased organ donors. As will be further discussed throughout this report, a number of deceased organ donor intervention studies have already been conducted in which the donor organs were transplanted into organ recipients. However, because of the complexities of the organ donation and transplantation process—such as those that arise when one donor provides multiple organs that might be transplanted in different transplant centers across the United

___________________

1 The committee for this study was not tasked with evaluating research on interventions administered after the transplant candidate has received an organ.

States—and because of the need to make decisions rapidly once organs become available, this type of research has proven challenging to conduct under the current U.S. policy and regulations regarding biomedical research (Abt et al., 2013; Glazier et al., 2015) (see Chapters 2 and 3).

In 2010, discussions about deceased organ donor intervention research began among a consortium of transplant organizations. These discussions resulted in work conducted by the Donor Intervention Research Expert Panel (DIREP) through the Organ Donation & Transplantation Alliance. DIREP examined the relevant issues and submitted its findings to the Health Resources & Services Administration in 2015 (Abt et al., 2015). Recommendations were also submitted to the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) through the Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Organ Transplantation.

On July 14, 2015, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies) held a planning meeting to bring together interested individuals from professional associations, transplant programs, OPOs, foundations, federal agencies, and others to discuss the need for and scope of a potential study. The planning meeting participants determined that there was a need for a detailed and independent study to explore the complexities of deceased organ donor intervention research and recommend a path forward, and the planning meeting resulted in a draft scope of work for the study. In response, a group of sponsors—American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American Society of Transplant Surgeons, American Society of Transplantation, Association of Organ Procurement Organizations, Gift of Life Donor Program, Health Resources & Services Administration, Laura and John Arnold Foundation, National Institutes of Health (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases), National Kidney Foundation, OneLegacy Foundation, and The Transplantation Society—funded a National Academies study on organ donor intervention research.

To address the study statement of task (see Box 1-1), the National Academies appointed a 12-member committee with expertise in organ transplant surgery, organ procurement, pediatrics, decision science, law, ethics, clinical trial research, and organ donation public awareness and education efforts. Brief biographies of each of the 12 committee members can be found in Appendix B. The committee held four in-person meetings, with the first two having public sessions with invited speakers. The committee also held two public information-gathering conference calls. The agendas for the public meetings can be found in Appendix A. In addition, the committee reviewed the published scientific literature and considered

information and input provided by the public and various agencies and organizations. After having examined the complexities and challenges surrounding organ donor intervention research, the committee identified six goals to guide its work (see Box 1-2).

OVERVIEW OF ORGAN DONATION AND TRANSPLANTATION

The process of organ transplantation begins with an authorization for organ donation. An individual’s decision to be an organ donor may be designated at any point during his or her lifetime through an authorization to be listed as an organ donor on a registry through the department of motor vehicles (when applying for a driver’s license or identification card) or through a state or national organ donor registry (see Chapter 3). The authorization for donation may also be made by a potential donor’s family or other designated surrogate after death (see Chapter 3). (Living donation is not included in the statement of task and thus not discussed in this report.)

In deceased organ donation, as the term indicates, the organ removal occurs only after an individual has been declared dead. The determination of death can be made in two ways: (1) it can be based on the irreversible cessation of all functions of the brain, including the functions of the brain stem (i.e., neurologic determination of death); or (2) it can be based on the irreversible cessation of circulatory and respiratory function (i.e., circulatory determination of death) (see discussion later in this chapter). Deceased organ donors are more commonly declared dead by neurologic determination of death, although the number of donors declared dead by circulatory determination of death is rising each year (OPTN, 2017f) (see Table 1-2). This is because in cases of neurologic determination of death, organ viabil-

ity can often be maintained through ventilatory support, thus increasing the likelihood of success for the transplantation. Donor-eligible deaths declared by neurologic determination of death are estimated to constitute 0.91 percent (9,793 deaths that were eligible for organ donation per the OPTN’s definition of an eligible death) of the 1,072,828 deaths and imminent deaths in the United States referred to OPOs in 2015 (Israni et al., 2017).

TABLE 1-2

U.S. Deaths Eligible for Organ Donation and Actual Donors, by Type, 2013–2015

| Parameter | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eligible deaths reported by DSAsa | 9,173 | 9,258 | 9,781 |

| Conversion rate (i.e., eligible deaths that become donors)b | 71.2% | 73.7% | 72.1% |

| Deceased donors—neurologic determination of death | 7,062 | 7,304 | 7,585 |

| Deceased donors—circulatory determination of death | 1,206 | 1,292 | 1,494 |

| Total deceased donors | 8,268 | 8,596 | 9,079 |

aOPTN/UNOS defines an eligible death as a death that meets established inclusionary criteria (e.g., neurologic determination of death, age 75 years or less) and without the presence of any exclusion criteria. Note that these inclusionary and exclusionary criteria vary by organ (OPTN, 2017b).

bPercentage of all eligible deaths that go on to become donors. The conversion rate uses donation service area (DSA) data and is calculated as the percentage of all eligible deaths that go on to become donors, after excluding all potential donors over 70 years of age and those deaths determined by circulatory criteria.

SOURCE: AOPO, 2017b.

Deaths determined by circulatory criteria often occur outside of the hospital or other medical facility. Organ donation after circulatory determination of death is possible, but there are often additional challenges to maintaining organ viability. These challenges include the delay between the cessation of circulatory and respiratory function and the recovery of organs for transplant, during which time the organs may be deprived of oxygen (Steinbrook, 2007). Efforts focused on increasing the potential for donation after circulatory determination of death continue to be implemented and further explored (Summers et al., 2015; Pabisiak et al., 2016; Wall et al., 2016; Jochmans et al., 2017; Miñambres et al., 2017; Scalea et al., 2017).

In the United States, organ donation and transplantation are accomplished through a cooperative, interdependent network of multidisciplinary, multi-institutional services. Oversight of this highly regulated process is coordinated by the federally mandated OPTN. UNOS operates the OPTN under a contract with the federal government. OPTN sets national policies for organ donation and transplantation which apply across all organizations involved in organ donation and transplantation—including OPOs, donor hospitals, and transplantation programs and centers (see Box 1-3).

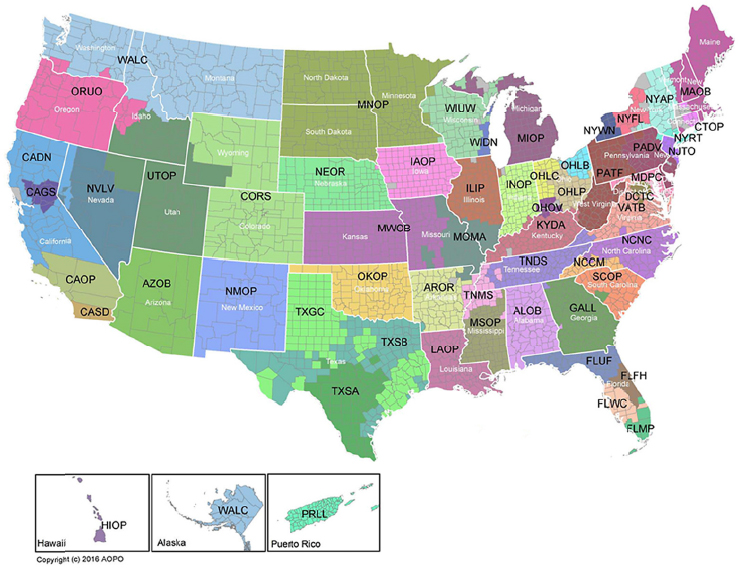

As detailed in Table 1-3, there are 58 OPOs responsible for procuring and distributing organs to 254 transplant centers. Different programs within these hospital centers are responsible for the transplantation of specific organs and the follow-up care for organ transplant recipients.

Additionally, 152 histocompatibility laboratories are responsible for conducting pre-allocation donor and recipient histocompatibility testing, and there is an extensive national computerized network used to match donated organs with potential recipients (UNOS, 2015c; OPTN, 2017e).

The network operates in units referred to as donation services areas (DSAs). Each DSA encompasses one OPO, the donor hospitals contracted to work with the OPO, and the assigned transplant hospitals, transplant programs, and histocompatibility labs that serve the service area. The 58 DSAs are geographically and culturally diverse (see Figure 1-3) and work within the nation’s 11 transplant regions.

DSAs act as semi-autonomous units. Historically they worked to procure and transplant organs locally, that is, within their DSA. However, because of recent advances in transplantation science and in efforts to reduce geographic disparities, changes have been made to the organ allocation system so that allocation increasingly functions on a more national scale—which is managed by OPTN/UNOS—and therefore organs can be shared across DSA boundaries (Davies et al., 2017; OPTN, 2017j).

Because the demand for donor organs exceeds the supply, individuals who need an organ transplant must be placed on a waiting list for the type(s) of organ they need. Criteria for being placed on the waiting list and the amount of time spent waiting on the list prior to receiving a transplant differ depending on the type of organ needed and the DSA in which the donor is waitlisted (Davis et al., 2014; Davies et al., 2017; OPTN, 2017j). An extensive discussion of the reasons for these differences is beyond the

TABLE 1-3

OPTN Members and Transplantation Statistics

| UNOS Region | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPOsa (DSAs) | 2 | 5 | 10 | 4 | 8 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 58 |

| Transplant centersa | 14 | 35 | 31 | 31 | 33 | 9 | 22 | 20 | 16 | 20 | 25 | 254 |

| Histocompatability laboratoriesa | 10 | 18 | 16 | 16 | 23 | 4 | 15 | 9 | 11 | 13 | 17 | 152 |

| Transplant procedures performed using organs from deceased donorsb | 1,116 | 3,454 | 3,995 | 2,867 | 4,608 | 885 | 2,232 | 1,703 | 2,386 | 1,631 | 2,753 | 27,630 |

NOTES: Seven OPTN members operate both transplant centers and in-house OPOs, and 97 operate both transplant centers and in-house histocompatibility laboratories. DSA = donation service area; OPO = organ procurement organization; OPTN = Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network.

aData as of July 13, 2017.

b2016 data.

SOURCES: OPTN, 2017e,f.

SOURCE: AOPO, 2017a. Reprinted with permission from AOPO.

scope of this report, but, in brief, waiting list criteria were developed with the goal of ensuring that donor organs are used optimally (i.e., in such a way as to minimize death among transplant candidates on the waiting list) and that they are allocated in an ethical, fair, and equitable manner. Thus, for each organ the candidates on the waiting list who are medically able to receive a transplant and who are at the greatest risk of dying without a transplant are given priority (UNOS, 2015b). Factors associated with dying from end-stage organ failure differ among organs. Therefore, the criteria used to objectively determine priority to receive a transplant vary depending on the organ in question (OPTN, 2017i). For example, patients suffering end-stage kidney disease can be supported by dialysis for extended periods of time. However, despite recent improvements, the 5-year survival of patients with end-stage kidney disease remains low when compared to survival following deceased donor transplant, 42 percent versus 76 percent, as of 2009 (Saran et al., 2017). Hence, the time spent on the waiting list is one of the most decisive factors in determining patient priority to receive a donor kidney (OPTN, 2017i). On the other hand, for patients

with end-stage liver disease—who have no therapeutic options that can replace liver function—a patient’s risk of dying is calculated using physiologic parameters, and this calculated risk is used to determine the patient’s priority to receive a donor liver (OPTN, 2017i). Even with these efforts to prioritize the most dire cases, thousands of patients die each year for want of a donor organ.

The 58 OPOs in the United States are responsible for obtaining and verifying authorizations for organ donations and for working with donor hospitals to procure and allocate organs from deceased donors. Depending on the condition of the deceased donor and the donor’s organs, an individual can donate up to eight solid organs (two kidneys, the pancreas, the heart, two lungs, the intestines, and the liver) which can be transplanted into eight or—if the liver and lungs are subdivided—even more recipients. In the time between the declaration of the donor’s death and the procurement of the donor’s organs, the authorized OPO and donor hospital implement donor management protocols that include administering medications, maintaining the deceased donor’s body at a particular temperature, and various other actions, all taken with the intent to maintain the organs in the best condition possible by minimizing organ stress, damage, and dysfunction until the organs are recovered (McKeown et al., 2012; Kotloff et al., 2015; Kumar, 2016).

If research followed by transplantation (organ donor intervention research) has been authorized, the research intervention would be administered to a deceased donor prior to organ recovery or to the target organ after the organ has been recovered but before transplantation. When the research intervention is administered prior to organ recovery and the intent is to have an effect on a specific organ (i.e., the target organ), the intervention could affect other organs from the same donor that may also be removed and transplanted after the intervention (i.e., non-target organs). As a result, many transplant recipients across multiple transplant centers could become human subjects in a single organ donor intervention research study.

The goals of such research are to improve the quality and increase the quantity of organs for transplantation—and, specifically, the intent of this research is to identify interventions that will allow the maximum number of transplantable organs to be recovered in a condition that will result in the best possible organ graft function in the recipient.

When an organ becomes available and a potential recipient is identified through the allocation process, the potential recipient’s transplant team is notified and provided with details about the organ. If the transplant team determines that the organ is acceptable, it will contact the potential recipient to determine his or her current state of health and interest in proceeding with the transplantation. In order that the organ be maintained in optimal condition, the decision of whether to accept an organ offer and move

forward with transplantation needs to be made quickly—usually within 1 hour of receiving the offer and accessing the deceased donor’s information (OPTN, 2017i)—and the transplantation surgery proceeds as soon as possible after the organ is accepted and received.

After transplantation, patients receive extensive follow-up care. Transplantation and follow-up data are submitted by transplant programs to OPTN/UNOS and analyzed by the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR). OPTN/UNOS and SRTR make the de-identified data available to the general public, clinicians, researchers, policy makers, and regulatory agencies. The data can be accessed by searching in multiple ways including by transplant program, recipient and donor demographics, the number and type of transplants performed, and the outcomes for organ grafts and transplant recipient survival within the first year after transplant.

Although practices vary by OPO, OPTN has issued broad guidance on the routine sharing of standard information and the coordination of communication between donor families and recipients. Communication following transplantation is largely dependent on the wishes of the donor’s family, who can receive information about which organs were transplanted and certain non-identifying information about the recipient (e.g., whether the recipient was young or old, whether the transplant was lifesaving, etc.). According to the guidance, recipients may express their gratitude through notes that are reviewed by and exchanged through the OPO to donor families, if they are receptive, and donor families may respond (OPTN, 2012).

TERMINOLOGY

Organ donation and transplantation elicit heightened sensitivities from the public. Because deceased organ donation involves the death of one human being resulting in the gift of one or more donor organs to one or more transplant candidates, the transplantation process is closely intertwined with the emotions that surround death and dying. Furthermore, organ donation and transplantation depend on upholding the public’s trust.

The committee carefully considered the terms used in this report and emphasizes—as do others in the donation and transplantation community—that the terms used to describe and the depiction of organ donation and transplantation need to be clear, accurate, transparent, and respectful. Honoring the donation and reflecting the high scientific rigor of this process are critical.

For this study, the terms used in discussing deceased donation are particularly relevant. Organ donor intervention research occurs after the determination of the donor’s death. Death is determined using neurologic or cardiac and respiratory criteria. Neurologic determination of death refers to the determination of death by irreversible cessation of all functions of the

brain including the functions of the brain stem. Circulatory determination of death indicates a determination of death made by observing the irreversible cessation of cardiac and respiratory function (i.e., the heart and lungs and other circulatory system components cease to function) (Bernat et al., 2006). The term “brain death” is sometimes used in cases where there is a neurologic determination of death, but the term is not entirely accurate because the declaration of death described in this manner does not account for the possibility of some remaining functions such as anterior pituitary neurohormonal regulation (Halevy and Brody, 1993).

The terms used to describe the removal of the organs from the deceased individual have evolved over time (IOM, 2006). Although the term “harvest” is no longer generally accepted or used because there is an impersonal nature to the word in the context of organ donation and because it has a largely agricultural context, it can still be heard occasionally. Similarly, the term “retrieve” may have an impersonal connotation. More generally accepted terms include “recover” or “receive” to highlight the gifting of the organ. The term “procure” is often used and has a transactional meaning, but more personal terms might be preferred. This report uses the terms “recover” and “procure.”

As noted throughout this report, one of the major challenges for organ donor intervention research is that an intervention conducted in the deceased donor’s body to improve the viability of one organ for transplantation (the target organ) may affect other organs (non-target organs). The term “non-target organs” focuses on the intent of the specific intervention. The term “bystander organs” has also been used, but the committee determined that this is less helpful as it suggests non-involvement or “observer” status rather than the potential to be impacted. Much remains to be learned about the impact of research interventions in deceased donors on the non-target organs.

There is debate about the best terms to use for an individual’s decision to donate his or her organs after death. The available literature and public policies use several of the following: “donation,” “consent to donation,” “authorization for donation,” “donor authorization,” “make an anatomical gift,” “become an organ donor,” “register as a donor,” “agree to donate,” etc. While each of these may be useful in some contexts, this report gives priority to the term “authorization,” both for the decedent’s prior decision to donate his or her organs and for the surrogate’s decision to donate those organs in the absence of the decedent’s prior decision. Not only is “authorization” now widely used with strong support in UNOS and elsewhere, but it can help avoid confusion in this report which also discusses consent for participation in research involving human subjects. The committee affirms what was previously said in the 2006 Institute of Medicine report: “As terms continue to evolve, the committee urges all who

are involved in organ transplantation to use words and phrases that clarify rather than mystify the process of organ transplantation and that affirm the value of each individual human life” (p. 31).

CONTEXT FOR THIS STUDY

Organs That May Pose Additional Risk for a Transplant Recipient

To ensure that potential recipients understand characteristics of donated organs that may impact their transplantation outcomes, policies have been developed to inform potential recipients about organs from donors that may have risks differing from those of the general population of deceased organ donors. The two categories, which vary based on requirements for informed consent and type of risk to the recipient, are expanded-criteria donors and increased-risk donors.

Expanded-Criteria Donors

Characteristics of some types of donors—for example, older age, circulatory determination of death, or biological measures above preferred thresholds—have been identified as being associated with a greater likelihood of the donated organ having poor function following transplantation (Rao and Ojo, 2009). Deceased donors who have characteristics that do not meet the OPTN/UNOS definition of an eligible death can be referred to as expanded-criteria donors.2

Current OPTN policy language defines a death as eligible for donation if the potential donor is age 75 years or less, declared dead by neurologic criteria, has at least one organ that meets organ-specific eligibility definitions, meets all other inclusionary criteria (weight, body mass index, etc.), and does not present with any exclusionary criteria. Some general exclusionary criteria include death from specific causes (e.g., certain cancers) and presence of certain infections (e.g., tuberculosis) (OPTN, 2017h). In terms of organ specific definitions, a kidney would be considered to not meet the OPTN definition of an eligible death if the potential donor is over 70 years of age or has a creatinine level of greater than 4.0 mg/dL. Additionally, a heart would not meet the definition if the potential donor is older than 60 years of age or has had a myocardial infarction (OPTN, 2017h). It should be noted that the OPTN definition of an eligible death is used by DSAs for reporting purposes and does not bar an OPO from moving forward with a donation from a potential donor (OPTN, 2017h). For

___________________

2 Kidneys are now classified using the “kidney donor profile index” rather than “expanded criteria donor,” a discussion of which is beyond the scope of this report.

example, in 2016, 2 hearts were transplanted from donors over the age of 65 years and in that same year 3,246 organs were transplanted from circulatory determination of death donors (OPTN, 2017f).

Concerns about the quality of expanded criteria donors or about particular donated organs result in many potential donors and donor organs being turned down for transplantation each year. Expanded-criteria organs can carry an increased risk of graft failure, dysfunction, or disease transmission (Rao and Ojo, 2009; Feng and Lai, 2014). However, such organs may provide better long-term health outcomes for a recipient than would be expected from not receiving an organ transplant at all (Doshi and Hunsicker, 2006; Rao and Ojo, 2009). Recent expansion of the criteria for acceptable kidney transplantation has allowed the transplant of a number of kidneys that previously would not have been recovered from the donors (Wynn and Alexander, 2011). Developing novel and innovative interventions that improve the outcomes for expanded criteria donor organs offers a significant opportunity to improve the quality and increase the number of deceased donor organs suitable for transplantation.

Increased Risk Donors

Deceased donors who have certain characteristics that increase the risk of transmission of an infectious disease to the recipient are classified by the U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS) as increased risk donors. In 2013, the USPHS published guidelines for the assessment and testing of organs from donors at increased risk for HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C (HCV)—all deceased donors are now tested for these diseases prior to organ recovery—and established a process for obtaining informed consent, a requirement for the use of increased risk organs, from transplant candidates who choose to accept these organ offers (Seem et al., 2013). The OPTN Ad Hoc Disease Transmission Advisory Committee released a guidance document on how to communicate with potential recipients regarding increased-risk donor organs (OPTN, 2017c). Beyond the increased risk classification for donors, researchers have recently explored the safety and efficacy of kidney transplantation from confirmed HCV positive donors to HCV negative recipients, followed by antiviral therapy for the recipient post-transplant as a strategy to expand the donor pool (Reese et al., 2015; Goldberg et al., 2017).

The HIV Organ Policy Equity (HOPE) Act legalized the transplant of organs from HIV-positive donors into HIV-positive recipients, in the setting of clinical research.3 On November 21, 2015, the Secretary of HHS finalized the OPTN standards of quality for the recovery and transplantation

___________________

3 HIV Organ Policy Equity Act, Public Law 113-51, 113th Cong. (November 21, 2013).

of organs from HIV-positive donors as required by the HOPE Act. The Secretary also published criteria for research relating to the transplantation of organs from HIV-positive donors into HIV-positive recipients, allowing the HOPE Act to take effect. The research criteria specify that organs from individuals infected with HIV may be transplanted only into individuals who are infected with HIV before receiving such organs and who are participating in clinical research approved by an institutional review board (Federal Register, 2015).

Organs Determined to Be Unsuitable for Transplantation

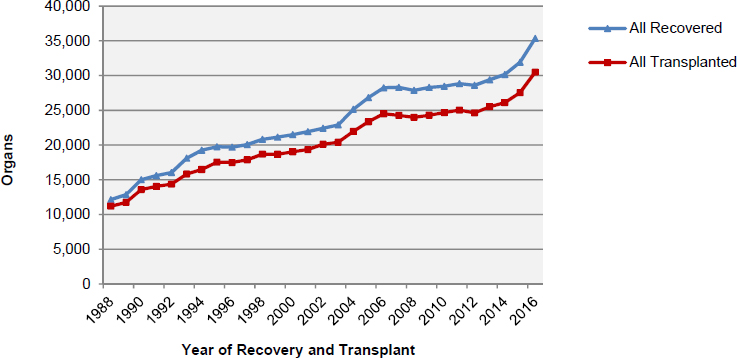

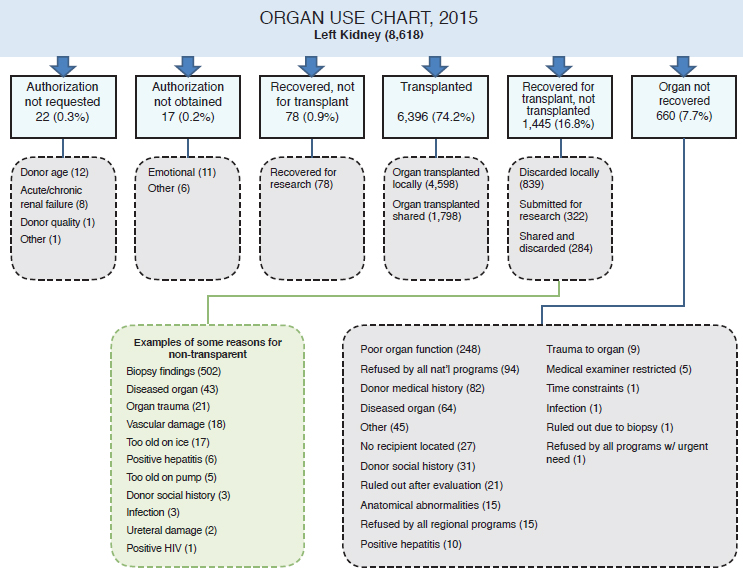

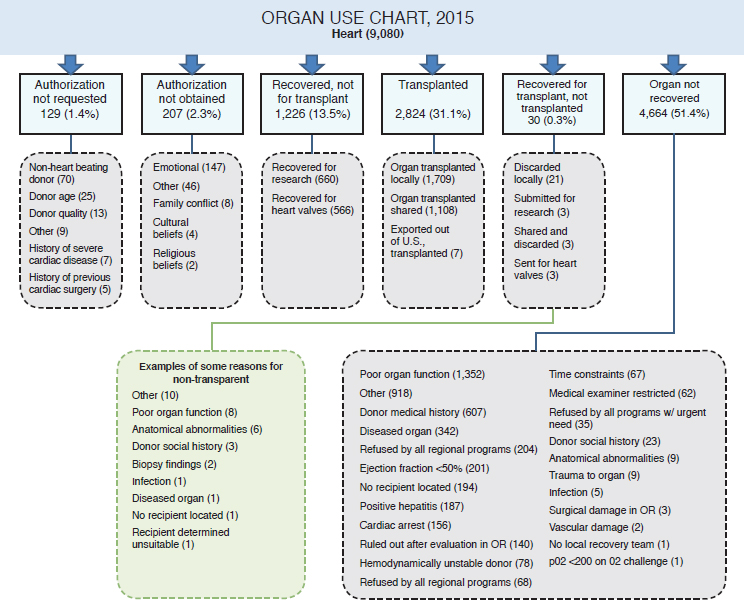

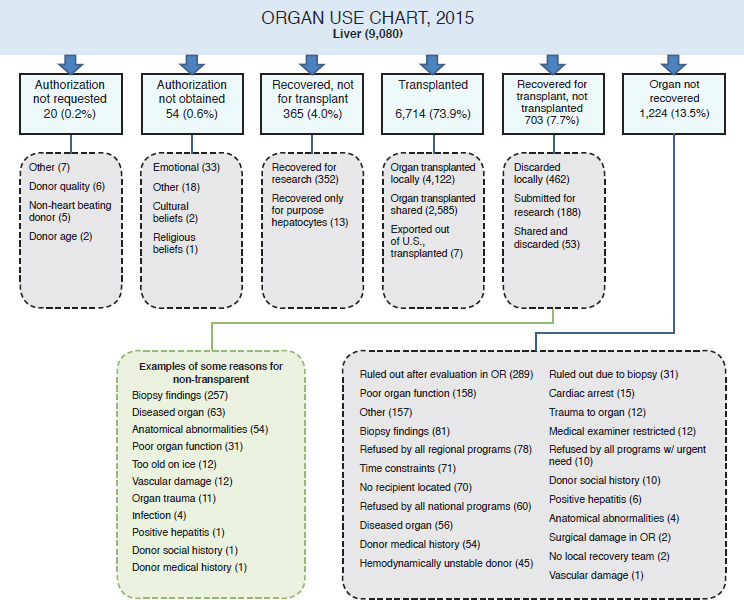

Despite the long waiting lists for donated organs, every year some organs that are recovered for use in transplantation are subsequently determined to be unsuitable for this purpose (see Figures 1-4 and 1-5 and Table 1-4). Some of the reasons for making this determination include disease, injury to the organ, and the elapse of too much time between recovery and transplantation (Israni et al., 2017).

Many organs that are recovered from deceased donors for transplantation, but not transplanted are used for research purposes (i.e., research that is not followed by transplantation). In some cases these organs are known prior to recovery to be unsuitable for transplantation but often they are determined to be unsuitable only after recovery. In both types of cases, some of the recovered organs may be useful for research purposes (see Table 1-5), while others will not be useful for research or any other purpose (e.g.,

SOURCE: Data from OPTN, 2017f.

SOURCE: Data from OPTN, 2017f.

TABLE 1-4

Organs from Deceased Donors Discarded in 2016, by Type

| Organ | Number |

|---|---|

| Intestines | 8 |

| Hearts | 31 |

| Lungs | 221 |

| Pancreases | 320 |

| Livers | 741 |

| Kidneys | 3,631 |

| Total discarded | 4,952 |

NOTE: This table does not include the number of organs from authorized donors that were never recovered for transplant. Please see Figures 1-6, 1-7, and 1-8 for more detail.

SOURCE: OPTN, 2017f.

TABLE 1-5

Recovered Organs Used for Research Purposes, 2013–2015

| Parameter | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|

| All deceased donors | 8,268 | 8,596 | 9,079 |

| Organs recovered for transplant but ultimately submitted to research | 811 | 1,067 | 1,080 |

| Organs recovered for research purposes | 3,265 | 4,214 | 4,549 |

| Total research organs | 4,076 | 5,281 | 5,629 |

NOTE: Data are not available to delineate organs that were used in a research capacity and that were later transplanted.

SOURCE: AOPO, 2017b.

education). With nearly 5,000 organs discarded from deceased donors in 2016 alone (see Table 1-4), there is the potential to perform more transplant surgeries and save more lives if new methods to improve organ quality and preservation can be developed. Such opportunities for developing these new methodologies could also exist by utilizing unused organs, those organs that are currently not recovered for transplant. Organ donor intervention research presents an opportunity to discover methods to improve organ quality and viability. Figures 1-6, 1-7, and 1-8 provide three examples (left kidney, heart, and liver, respectively) illustrating how some organs were used after recovery in 2015. Some of the areas in which organ donor intervention research may have a substantial impact are in those organs that are not transplanted because of poor organ function, vascular damage, and organ trauma. While there will continue to be organs that are not suitable for transplantation, reducing that number is a goal worth pursuing.

Time Constraints in the Organ Donation and Transplantation Process

After an organ is recovered from a donor, there is a window of time during which the organ can be preserved; once this window passes, the organ can no longer be reliably counted on to function adequately after transplantation. The length of preservation time varies by the organ type (see Table 1-6). Several activities must occur during this window of time, including (1) the allocation of the organ to a transplant candidate; (2) the offer to and acceptance of the organ by the transplant candidate and the transplant team; (3) admission of the transplant candidate to the hospital, which may be complicated by a candidate’s lack of proximity to the hospital; (4) transporting the organ from the donor’s hospital to the transplant

SOURCE: Adapted from Israni et al., 2017.

candidate’s hospital; (5) obtaining clinical consent from the transplant candidate for surgery, and pre-operative evaluation of the transplant candidate; and (6) pre-operative preparation of the candidate. Hence, a transplant candidate and his or her transplantation team have only a short period of time during which to decide whether to accept a given organ, particularly if the organ is a heart or a lung.

Geographic Disparities in Organ Allocation

Because of past challenges in transporting organs and maintaining their viability, until recently the organ allocation system has focused primarily on local or regional allocation. However, there has been some discussion about the division of regions for particular organs because some regions have longer waiting lists than others do. For instance, the waiting list for a liver in Massachusetts is much longer than the waiting lists in Florida and

NOTE: OR = operating room.

SOURCE: Adapted from Israni et al., 2017.

South Carolina because the supply of organs in the latter states is greater relative to the number of transplant candidates on the waiting lists (Ladin et al., 2017). Ladin and colleagues (2017) proposed that this may be due in part to such factors as the residents of Massachusetts having greater access to health care and fewer deaths that would increase the organ supply (e.g., from motor vehicle accidents).

For some organs there is now the possibility of moving toward allocation algorithms that prioritize candidates across the country rather than those who are local to the location of the deceased donor. Allocation policies are being reviewed to balance the goal of creating a more equitable system with the goal of promoting efficiency. For example, OPTN is evaluating changing geographic boundaries for the allocation of livers (OPTN, 2017j); however, this has been met with controversy (Kowalczyk, 2016; Naugler, 2016; OPTN, 2016, 2017j) and remains a topic of ongoing discussion (OPTN, 2017g).

NOTE: OR = operating room.

SOURCE: Adapted from Israni et al., 2017.

TABLE 1-6

General Maximum Preservation Time, by Organ

| Organ | Preservation Time |

|---|---|

| Heart and lungs | 4 to 6 hours |

| Liver | 8 to 12 hours |

| Pancreas | 12 to 18 hours |

| Kidney | 23 to 36 hours |

SOURCE: OPTN, 2017d.

DISTINGUISHING RESEARCH FROM QUALITY IMPROVEMENT STUDIES

The focus of this report is on research—specifically, deceased organ donor intervention research. However, the committee recognized that improvements in donor management have frequently resulted from quality improvement (QI) studies and noted that there is ongoing discussion about the boundaries between quality improvement and research in this field, as in many areas of clinical medicine (Casarett et al., 2000; Baily et al., 2006). QI and research are the two fundamental processes used to improve clinical practice, and organ donor management and transplantation efforts are already enmeshed with innovative procedures, formal research protocols, and the introduction of new interventions with deceased donor organs that fall somewhere on the spectrum between quality improvement and translational research.

What constitutes research versus quality improvement? Definitions that have been used for each term highlight some of the characteristics that can be used to differentiate QI from research:

- Quality improvement: “systematic, data-guided activities designed to bring about immediate, positive changes in the delivery of health care in particular settings” (Baily et al., 2006, p. S5).

- Research: “systematic investigation, including research development, testing and evaluation, designed to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge.”4

Casarett and colleagues distinguished the two terms based on “if (a) whether the majority of patients involved are not expected to benefit directly from the knowledge to be gained, and (b) if additional risks or burdens are imposed to make the results generalizable” (2000, p. 2275). QI studies are often used to address deficiencies and disparities in the provision of health care by developing protocols, checklists, and other morbidity reducing measures to identify and implement morbidity reducing measures or to put protocols in place to adhere to standards of care and best practices (Howard et al., 2007; HRSA, 2011; Seoane et al., 2013).

The goals of QI and research differ. QI uses data-guided testing that is designed to bring about immediate improvements in the delivery of clinical care. QI activities take place in a continually changing environment and may be simply considered good clinical practice combined with systematic, experiential learning (Davidoff et al., 2008).

___________________

4 45 C.F.R. § 46.102.

On the other hand, the goal of research is to conclusively test the effectiveness and safety of interventions through a convention of rigorous systematic investigation—most commonly, randomized controlled trials. As noted by Baily and colleagues (2006),

Allowing research subjects to assume the burdens and risks of research is justified by the expectation of societal benefits from the new knowledge produced; publication is an important step in conveying the new knowledge to those who can put it into practice and thereby create the social benefits. Although the [HHS] definition does not make it explicit, the regulations implicitly reflect a view of research as a knowledge-seeking enterprise that is independent of routine medical care. (p. S11)

Attention to this issue is particularly pertinent to the field of organ donor intervention studies because of the potential impact an intervention may have on multiple individuals at multiple medical facilities and given the priority of ensuring that appropriate human subjects research protections are in place. In Chapter 4 the committee discusses this issue further with regard to the oversight of organ donor intervention studies.

CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES IN ORGAN DONOR INTERVENTION RESEARCH

Deceased organ donor intervention research offers an opportunity to gain the knowledge needed to maximize the benefits of the gifts of donated organs. This research involves challenges that are both similar to and different from other forms of clinical research (see Box 1-4). The committee’s work focused on identifying next steps in overcoming these challenges so that research can be conducted that will improve the quality and increase the quantity of organs available for transplantation. This research is a critical component within a range of ongoing initiatives and not yet fully tapped opportunities—including public education efforts, organ donor registry and policy and regulatory changes—that have the potential to further increase organ donation and opportunities for transplantation and, as a result, to improve the health and well-being of many individuals.

ORGANIZATION OF THIS REPORT

This report covers the breadth of the committee’s statement of task. Chapter 2 outlines the ethics principles—respect for persons, beneficence/utility, fairness, validity, and trustworthiness—that are the basis for moving forward with organ donor intervention research. In Chapter 3 the committee explores the legal, regulatory, and policy framework for organ

donation and research participation relevant to organ donor intervention research and sets forth its recommendations for interpreting, applying, and in some instances, revising that framework. The report concludes in Chapter 4 with the rationale and structure for centrally administered oversight of this research focusing on the essential functions needed to maintain and sustain the integrity and trustworthiness of the nation’s organ donation and transplantation system.

REFERENCES

Abt, P. L., C. L. Marsh, T. B. Dunn, W. R. Hewitt, J. R. Rodrigue, J. M. Ham, and S. Feng. 2013. Challenges to research and innovation to optimize deceased donor organ quality and quantity. American Journal of Transplantation 13(6):1400-1404.

Abt, P., R. D. Hasz, D. Nelson, A. Glazier, K. G. Heffernan, C. Niemann, and S. Feng. 2015. Letter to Division of Transplantation, Health Resources & Services Administration from the Donor Intervention Research Expert Panel (DIREP). http://organdonationalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/FINAL-DIREP-Letter-090215.pdf (accessed August 29, 2017).

AOPO (Association of Organ Procurement Organizations). 2017a. Donation Service Areas. http://www.aopo.org/donation-service-areas (accessed Septem-ber 13, 2017).

AOPO. 2017b. DSA dashboard—Comprehensive data through September 2016. http://www.aopo.org/related-links-data-on-donation-and-transplantation (ac-cessed August 30, 2017).

Baily, M. A., M. Bottrell, J. Lynn, and B. Jennings. 2006. The ethics of using QI methods to improve health care quality and safety. Garrison, NY: Hastings Center.

Bernat, J. L., A. M. D’Alessandro, F. K. Port, T. P. Bleck, S. O. Heard, J. Medina, S. H. Rosenbaum, M. A. DeVita, R. S. Gaston, R. M. Merion, M. L. Barr, W. H. Marks, H. Nathan, K. O’Connor, D. L. Rudow, A. B. Leichtman, P. Schwab, N. L. Ascher, R. A. Metzger, V. Mc Bride, W. Graham, D. Wagner, J. Warren, and F. L. Delmonico. 2006. Report of a National Conference on Donation after Cardiac Death. American Journal of Transplantation 6(2):281-291.

Casarett, D., J. H. T. Karlawish, and J. Sugarman. 2000. Determining when quality improvement initiatives should be considered research: Proposed criteria and potential implications. JAMA 283(17):2275-2280.

CMS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services). 2013. Transplant. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/GuidanceforLawsAndRegulations/Transplant-Laws-and-Regulations.html (accessed August 30, 2017).

Davidoff, F., P. Batalden, D. Stevens, G. Ogrinc, S. Mooney, and Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence Development Group. 2008. Publication guidelines for quality improvement studies in health care: Evolution of the SQUIRE project. Journal of General Internal Medicine 23(12):2125-2130.

Davies, R. R., M. Farr, S. Silvestry, L. R. Callahan, L. Edwards, D. M. Meyer, K. Uccellini, K. M. Chan, and J. G. Rogers. 2017. The new United States heart allocation policy: Progress through collaborative revision. Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation 36(6):595-596.

Davis, A. E., S. Mehrotra, L. M. McElroy, J. J. Friedewald, A. I. Skaro, B. Lapin, R. Kang, J. L. Holl, M. M. Abecassis, and D. P. Ladner. 2014. The extent and predictors of waiting time geographic disparity in kidney transplantation in the United States. Transplantation 97(10):1049-1057.

Doshi, M. D., and L. G. Hunsicker. 2007. Short- and long-term outcomes with the use of kidneys and livers donated after cardiac death American Journal of Transplantation 7(1):122-129.

Eidbo, E. 2017. United Network for Organ Sharing number of patient registrations on the national transplant waiting list 2/28/2017. Document provided to the Committee on Issues in Organ Donor Intervention Research, Washington, DC, May 12. Available by request through the National Academies’ Public Access Records Office.

Federal Register. 2015. Final human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) organ policy Equity (HOPE) act safeguards and research criteria for the transplantation of organs infected with HIV. Federal Register 80(227):73785-73796.

Feng, S. 2010. Donor intervention and organ preservation: Where is the science and what are the obstacles? American Journal of Transplantation 10(5):1155-1162.

Feng, S., and J. C. Lai. 2014. Expanded criteria donors. Clinics in Liver Disease 18(3):633-649.

Glazier, A. K., K. G. Heffernan, and J. R. Rodrigue. 2015. A framework for conducting deceased donor research in the United States. Transplantation 99(11):2252-2257.

Goldberg, D. S., B. French, G. Sahota, A. E. Wallace, J. D. Lewis, and S. D. Halpern. 2016. Use of population-based data to demonstrate how waitlist-based metrics overestimate geographic disparities in access to liver transplant care. American Journal of Transplantation 16(10):2903-2911.

Goldberg, D. S., P. L. Abt, E. A. Blumberg, V. M. Van Deerlin, M. Levine, K. R. Reddy, R. D. Bloom, S. M. Nazarian, D. Sawinski, P. Porrett, A. Naji, R. Hasz, L. Suplee, J. Trofe-Clark, A. Sicilia, M. McCauley, M. Farooqi, C. Gentile, J. Smith, and P. P. Reese. 2017. Trial of transplantation of HCV-infected kidneys into uninfected recipients. New England Journal of Medicine 376(24):2394-2395.

Halevy, A., and B. Brody. 1993. Brain death: Reconciling definitions, criteria, and tests. Annals of Internal Medicine 119(6):519-525.

Hart, A., J. M. Smith, M. A. Skeans, S. K. Gustafson, D. E. Stewart, W. S. Cherikh, J. L. Wainright, A. Kucheryavaya, M. Woodbury, J. J. Snyder, B. L. Kasiske, and A. K. Israni. 2017. OPTN/SRTR 2015 annual data report: Kidney. American Journal of Transplantation 17:21-116.

Heffernan, K. G., and A. K. Glazier. 2017. Are transplant recipients human subjects when research is conducted on organ donors? Hasting Center Report 47:1-5.

Howard, D. H., L. A. Siminoff, V. McBride, and M. Lin. 2007. Does quality improvement work? Evaluation of the Organ Donation Breakthrough Collaborative. Health Services Research 42(6 Pt 1):2160-2173.

HRSA (Health Resources & Services Administration). 2011. Quality improvement. https://www.hrsa.gov/quality/toolbox/methodology/qualityimprovement (accessed July 25, 2017).

HRSA. 2017. Find your local organ procurement organization. https://organdonor.gov/awareness/organizations/local-opo.html (accessed June 9, 2017).

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2006. Organ donation: Opportunities for action. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Israni, A. K., D. Zaun, C. Bolch, J. D. Rosendale, C. Schaffhausen, J. J. Snyder, and B. L. Kasiske. 2017. OPTN/SRTR 2015 annual data report: Deceased organ donation. American Journal of Transplantation 17:503-542.

Jochmans, I., M. van Rosmalen, J. Pirenne, and U. Samuel. 2017. Adult liver allocation in Eurotransplant. Transplantation 101(7):1542-1550.

Kandaswamy, R., P. G. Stock, S. K. Gustafson, M. A. Skeans, M. A. Curry, M. A. Prentice, A. K. Israni, J. J. Snyder, and B. L. Kasiske. 2017. OPTN/SRTR 2015 annual data report: Pancreas. American Journal of Transplantation 17:117-173.

Kim, W. R., J. R. Lake, J. M. Smith, M. A. Skeans, D. P. Schladt, E. B. Edwards, A. M. Harper, J. L. Wainright, J. J. Snyder, A. K. Israni, and B. L. Kasiske. 2017. OPTN/SRTR 2015 annual data report: Liver. American Journal of Transplantation 17:174-251.

Kotloff, R. M., S. Blosser, G. J. Fulda, D. Malinoski, V. N. Ahya, L. Angel, M. C. Byrnes, M. A. DeVita, T. E. Grissom, S. D. Halpern, T. A. Nakagawa, P. G. Stock, D. L. Sudan, K. E. Wood, S. J. Anillo, T. P. Bleck, E. E. Eidbo, R. A. Fowler, A. K. Glazier, C. Gries, R. Hasz, D. Herr, A. Khan, D. Landsberg, D. J. Lebovitz, D. J. Levine, M. Mathur, P. Naik, C. U. Niemann, D. R. Nunley, K. J. O’Connor, S. J. Pelletier, O. Rahman, D. Ranjan, A. Salim, R. G. Sawyer, T. Shafer, D. Sonneti, P. Spiro, M. Valapour, D. Vikraman-Sushama, and T. P. Whelan. 2015. Management of the potential organ donor in the ICU: Society of Critical Care Medicine/American College of Chest Physicians/Association of Organ Procurement Organizations consensus statement. Critical Care Medicine 43(6):1291-1325.

Kowalczyk, L. 2016. A nation divided, even on organ transplants. The Boston Globe, December 24. https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2016/12/24/you-want-increase-your-chances-getting-liver-transplant-move-georgia/TbfleFMkaYqUzW11TSpl7I/story.html (accessed August 29, 2017).

Kumar, L. 2016. Brain death and care of the organ donor. Journal of Anaesthesiology Clinical Pharmacology 32(2):146-152.

Ladin, K., G. Zhang, and D. W. Hanto. 2017. Geographic disparities in liver availability: Accidents of geography, or consequences of poor social policy? American Journal of Transplantation 17(9):2277-2284.

McKeown, D. W., R. S. Bonser, and J. A. Kellum. 2012. Management of the heartbeating brain-dead organ donor. British Journal of Anaesthesia 108(Suppl 1):i96-i107.

Miñambres, E., B. Suberviola, B. Dominguez-Gil, E. Rodrigo, J. C. Ruiz-San Millan, J. C. Rodriguez-San Juan, and M. A. Ballesteros. 2017. Improving the outcomes of organs obtained from controlled donation after circulatory death donors using abdominal normothermic regional perfusion. American Journal of Transplantation 17(8):2165-2172.

Naugler, W. E. 2016. California has long wait lists for liver transplants, but not for the reasons you think Los Angeles Times, December 13. http://www.latimes.com/opinion/op-ed/la-oe-naugler-liver-transplant-rules-20161213-story.html (accessed August 29, 2017).

OPTN (Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network). 2012. Guidamce for donor and recipient information sharing. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/resources/guidance/guidance-for-donor-and-recipient-information-sharing (accessed July, 24, 2017).

OPTN. 2016. OPTN/UNOS Liver & Intestinal Organ Transplantation Committee: Report to the board of directors. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/media/1995/liver_boardreport_201612.pdf (accessed June 23, 2017).

OPTN. 2017a. About the OPTN. https://optn.transplant.hrsa/gov/governance/about-the-optn (accessed June 8, 2017).

OPTN. 2017b. Glossary. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/resources/glossary (accessed July 13, 2017).

OPTN. 2017c. Guidance on explaining risk related to use of U.S. PHS increased risk donor organs when considering organ offers. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/media/2171/dtac_boardreport_201706.pdf (accessed June 23, 2017).

OPTN. 2017d. How organ donation works. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/learn/about-transplantation/how-organ-allocation-works (accessed July 13, 2017).

OPTN. 2017e. Members. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/members (accessed July 13, 2017).

OPTN. 2017f. National data. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/view-data-reports/national-data/# (accessed July 13, 2017).

OPTN. 2017g. OPTN/UNOS Liver and Intestinal Organ Transplantation Committee: Meeting minutes from May 18, 2017 conference call. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/media/2188/liver_meetingsummary_20170518.pdf (accessed June 23, 2017).

OPTN. 2017h. OPTN/UNOS policy notice: Eligible death data definitions. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/media/2012/opo_policynotice_ie_20130701.pdf (accessed July 24, 2017).

OPTN. 2017i. Policies. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/media/1200/optn_policies.pdf (accessed May 19, 2017).

OPTN. 2017j. Redesigning liver distribution. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/governance/public-comment/redesigning-liver-distribution (accessed June 22, 2017).

Pabisiak, K., A. Krejczy, G. Dutkiewicz, K. Safranow, J. Sienko, R. Bohatyrewicz, and K. Ciechanowski. 2016. Nonaccidental out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in an urban area as a potential source of uncontrolled organ donors. Annals of Transplantation 21:582-586.

Patzer, R. E., L. C. Plantinga, S. Paul, J. Gander, J. Krisher, L. Sauls, E. M. Gibney, L. Mulloy, and S. O. Pastan. 2015. Variation in dialysis facility referral for kidney transplantation among patients with end-stage renal disease in Georgia. JAMA 314(6):582.

Rao, P. S., and A. Ojo. 2009. The alphabet soup of kidney transplantation: SCD, DCD, ECD fundamentals for the practicing nephrologist. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 4(11):1827-1831.

Reese, P. P., P. L. Abt, E. A. Blumberg, and D. S. Goldberg. 2015. Transplanting hepatitis C–positive kidneys. New England Journal of Medicine 373(4):303-305.

Saran, R., B. Robinson, K. C. Abbott, L. Y. C. Agodoa, P. Albertus, J. Ayanian, R. Balkrishnan, J. Bragg-Gresham, J. Cao, J. L. T. Chen, E. Cope, S. Dharmarajan, X. Dietrich, A. Eckard, P. W. Eggers, C. Gaber, D. Gillen, D. Gipson, H. Gu, S. M. Hailpern, Y. N. Hall, Y. Han, K. He, P. Hebert, M. Helmuth, W. Herman, M. Heung, D. Hutton, S. J. Jacobsen, N. Ji, Y. Jin, K. Kalantar-Zadeh, A. Kapke, R. Katz, C. P. Kovesdy, V. Kurtz, D. Lavallee, Y. Li, Y. Lu, K. McCullough, M. Z. Molnar, M. Montez-Rath, H. Morgenstern, Q. Mu, P. Mukhopadhyay, B. Nallamothu, D. V. Nguyen, K. C. Norris, A. M. O’Hare, Y. Obi, J. Pearson, R. Pisoni, B. Plattner, F. K. Port, P. Potukuchi, P. Rao, K. Ratkowiak, V. Ravel, D. Ray, C. M. Rhee, D. E. Schaubel, D. T. Selewski, S. Shaw, J. Shi, M. Shieu, J. J. Sim, P. Song, M. Soohoo, D. Steffick, E. Streja, M. K. Tamura, F. Tentori, A. Tilea, L. Tong, M. Turf, D. Wang, M. Wang, K. Woodside, A. Wyncott, X. Xin, W. Zeng, L. Zepel, S. Zhang, H. Zho, R. A. Hirth, and V. Shahinian. 2017. US renal data system 2016 annual data report: Epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 69(3 Suppl 1):S1-S688.

Scalea, J. R., R. R. Redfield, E. Arpali, G. E. Leverson, R. J. Bennett, M. E. Anderson, D. B. Kaufman, L. A. Fernandez, A. M. D’Alessandro, D. P. Foley, and J. D. Mezrich. 2017. Does DCD donor time-to-death affect recipient outcomes? Implications of time-to-death at a high-volume center in the United States. American Journal of Transplantation 17(1):191-200.

Seem, D. L., I. Lee, C. A. Umscheid, M. J. Kuehnert, and U.S. Public Health Service. 2013. PHS guideline for reducing human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C virus transmission through organ transplantation. Public Health Reports 128(4):247-343.

Seoane, L., F. Winterbottom, T. Nash, J. Behrhorst, E. Chacko, L. Shum, A. Pavlov, D. Briski, S. Thibeau, D. Bergeron, T. Rafael, and E. Sundell. 2013. Using quality improvement principles to improve the care of patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. The Ochsner Journal 13(3):359-366.

Smith, J. M., M. A. Skeans, S. P. Horslen, E. B. Edwards, A. M. Harper, J. J. Snyder, A. K. Israni, and B. L. Kasiske. 2017. OPTN/SRTR 2015 annual data report: Intestine. American Journal of Transplantation 17:252-285.

SRTR (Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients). 2017. Driven to make a difference: Mission, vision, and values. https://www.srtr.org/about-srtr/mission-vision-and-values (accessed June 29, 2017).

Steinbrook, R. 2007. Organ donation after cardiac death. New England Journal of Medicine 357(3):209-213.

Summers, D. M., C. J. E. Watson, G. J. Pettigrew, R. J. Johnson, D. Collett, J. M. Neuberger, and J. A. Bradley. 2015. Kidney donation after circulatory death (DCD): State of the art. Kidney International 88(2):241-249.

UNOS (United Network for Organ Sharing). 2015a. About. https://www.unos.org/about (accessed September 12, 2017).

UNOS. 2015b. How organ matching works. https://www.unos.org/transplantation/matching-organs (accessed July 24, 2017).

UNOS. 2015c. Technology for transplantation. https://www.unos.org/data/technology-for-transplantation (accessed June 7, 2017).

UNOS. 2017. Strategic goals. https://www.unos.org/about/strategic-goals (accessed June 8, 2017).

Wall, S. P., B. J. Kaufman, N. Williams, E. M. Norman, A. J. Gilbert, K. G. Munjal, S. Maikhor, M. J. Goldstein, J. E. Rivera, and H. Lerner. 2016. Lesson From the New York City out-of-hospital uncontrolled donation after circulatory determination of death program. Annals of Emergency Medicine 67(4):531-537.

Wynn, J. J., and C. E. Alexander. 2011. Increasing organ donation and transplantation: The U.S. experience over the past decade. Transplant International 24(4):324-332.