Proceedings of a Workshop

| IN BRIEF | |

October 2017 |

Demographic Effects of Girls’ Education in Developing Countries

Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief

SETTING THE STAGE

Workshop chair Ann Blanc (Population Council) opened the workshop by reminding participants of the four issues the speakers had been asked to address:

- Consider the effects of girls’ education on their reproductive behavior, especially the level and pattern of childbearing and timing of such reproductive events as age at marriage and first birth.

- Analyze the reverse causality between early union formation and childbearing on girls’ educational attainment.

- Examine the mechanisms by which education, including educational quality, school contexts, and curricula, affects demographic outcomes.

- Discuss the policy and program implications of the research on girls’ education.

![]()

GIRLS’ EDUCATION AND REPRODUCTIVE BEHAVIOR

Although UNESCO declared in 2014 that gender parity has been achieved in education, Stephanie Psaki (Population Council) offered some caveats to that declaration. Using Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) data from 43 countries, she showed that although gender gaps in enrollment and attainment are declining in many countries, many young people, especially girls, never enter school, and there continue to be gender gaps in skills, such as literacy. She pointed out that the lack of gender disparities in many countries may reflect very low levels of attainment overall, rather than success in girls attending school. Moreover, Psaki said, completion of primary school does not necessarily translate into basic literacy. She suggested that future investments in girls’ education should focus on primary school enrollment for girls, educational attainment for all, closing gender gaps in low enrollment settings, and maintaining or improving the quality of schooling as enrollment increases.

Using the same DHS data from 43 countries, Ann Blanc focused on the trends in reproductive transitions and education levels over the last few decades. She measured three key events in the transition to adulthood: age at first sex, age at first marriage, and age at first birth. She found that education was generally positively associated with age at these reproductive events, except in Latin America: contrary to the patterns observed in other world regions, for each education group the age at first sex and first birth was getting younger over time.

Blanc highlighted that the trend in timing of reproductive events depends on the speed of trends in levels of education, changing selectivity, other secular changes, and declining quality of schooling. The very strong relationships between education and timing of reproductive events are changing over time. Importantly, she noted, if learning is part of the causal pathway, a decline in school quality will affect the pathway between education and reproductive transitions.

Anne Goujon (Vienna Institute of Demography and International Institute for Applied Sys-

Source: Presentation by Desai and Natta (2017). Life Scripts: Education and Demographic Aspirations among Indian Girls. Workshop on Demographic Effects of Girls’ Education in Developing Countries.

tems Analysis) expanded the discussion of education and demographic behavior by exploring the link among structural adjustment programs, educational discontinuities, and stalled fertility in sub-Saharan Africa. Using DHS data, Goujon found that in countries in which the fertility decline has not stalled, there is decline in fertility for all cohorts. However, for countries in which the fertility decline has stalled, there is an increase in age-specific fertility rates: the fertility stalls were for a cohort that experienced a stall in intercohort educational progress, which was caused in many cases by a decline in spending on education triggered by structural adjustment programs. The effect of the stall in education was early fertility. Several participants expressed curiosity that education only affected early fertility and not the whole reproductive life span. Goujon agreed that the evidence suggests a tempo effect with women preponing their fertility.

CLARIFYING PATHWAYS AND DELINEATING MECHANISMS

Sonalde Desai (Department of Sociology, University of Maryland) began her presentation by setting the context and illuminating possible pathways between girls’ education and demographic outcomes. She noted that although it is well established that higher education is associated with the preference for later age at marriage, important questions remain about what exactly education does to transform girls’ preferences and their ability to carry them out.

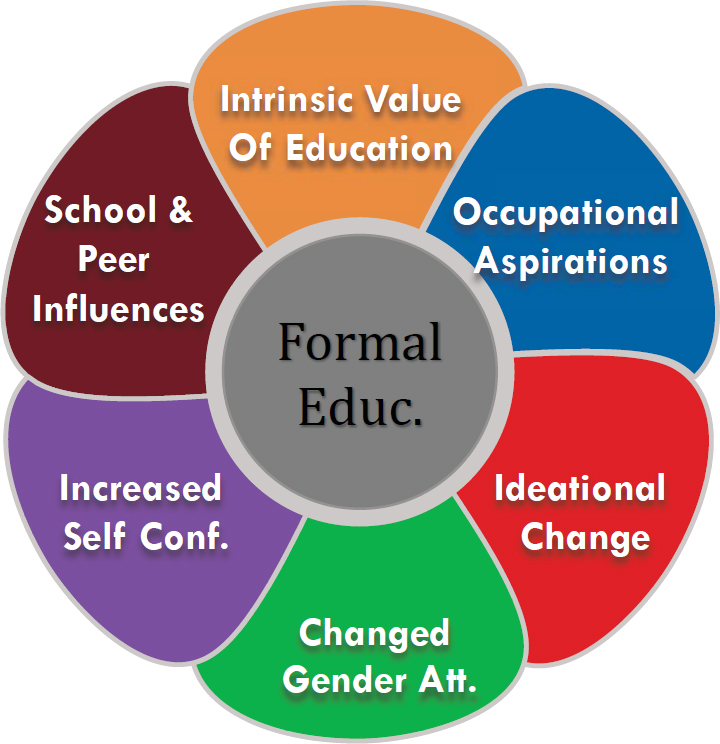

She noted that possible pathways between education and demographic events include occupational aspirations, ideational changes, changes in gender attitudes, increased self-confidence, school and peer influences, and the intrinsic value of education: see Figure 1. These pathways fit into three primary clusters: ideational (such as gender and ideal family struc-

Source: Presentation by Aurino, Behrman, Penny, and Schott (2017). Education and Adolescent Motherhood: Evidence from Ethiopa, India, Peru, and Vietnam. Workshop on Demographic Effects of Girls’ Education in Developing Countries.

ture), academic and occupational aspirations (such as academic skills and employment preferences), and personal strength (such as self-confidence and the ability to negotiate).

Through interviews with Indian girls and their parents, Desai found that education did not have an effect on their attitudes about gender roles. However, education was associated with greater self-confidence and the ability to handle familial situations. Education was also associated with increased reading and Internet use and more diverse friendship networks. She concluded that education shapes marital age preferences by offering an alternative social environment through schools. The girls who have gained academic skills are the ones who are actually delaying marriage.

Desai pointed out that although having a causal story is important, many events in girls’ lives are jointly determined: sometimes observers and researchers lose the forest for the trees with an exclusive focus on causality. She said that experimental and conceptual work can feed off of one another, reinforce findings, and ultimately uncover the mechanisms that are affecting girls’ lives.

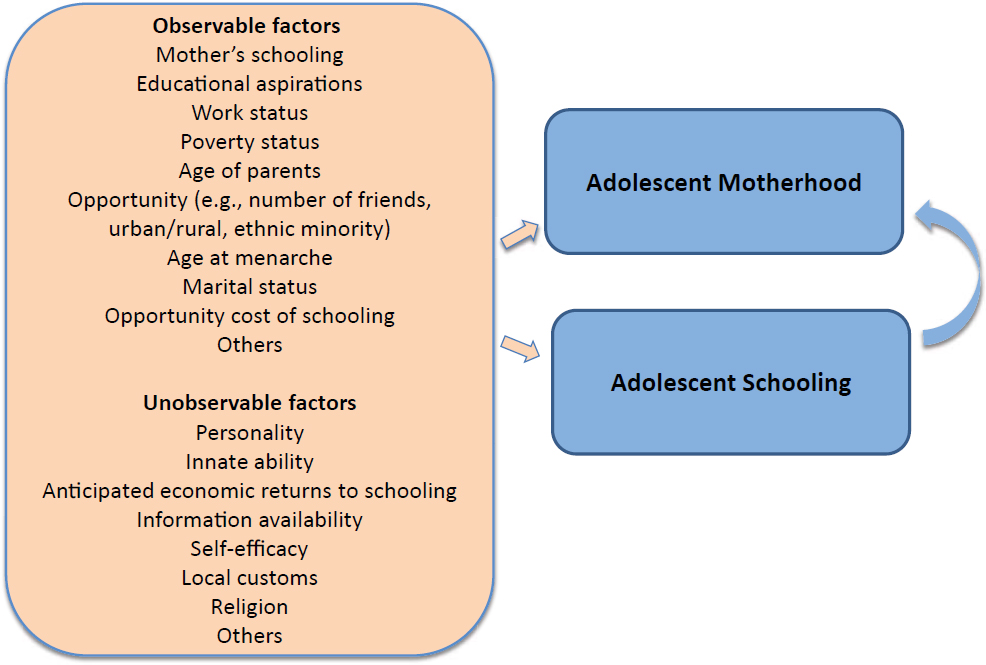

Elisabetta Aurino (Center for Health Economics and Policy Innovations, Imperial College London) and Whitney Schott (Population Studies Center, University of Pennsylvania) addressed the question of causality, noting that adolescent schooling and motherhood demonstrate an endogeneity issue as they are jointly determined by a set of observable and unobservable factors. She explained that her work with Schott used an instrumental variables approach to account for endogeneity in examining the relationship between education and adolescent motherhood in Ethiopia, India, Peru, and Vietnam (see Figure 2).

Schott provided a rich set of descriptive statistics that set the scene on the longitudinal samples from the Young Lives Study. This descriptive work pointed to a wide cross-country variation in terms of girls’ demographic outcomes as well as their educational trajectories. For a pooled sample, a multivariate analysis showed that each additional year of schooling was associated with 10 percent lower probability of becoming a mother by the age of 19. The instrumental variables included minutes to travel to school, average years of schooling of adolescent’s mother, number of older siblings in the household, and number of children under age 6 in the household. The authors also noted the inherent difficulties in identifying adequate variables that can meaningfully address the endogeneity in the fertility–education relation.

The participants discussed whether the instrumental variables chosen were appropriate. Many of the participants commented that maternal education should not be used because it is linked to pregnancy, but that minutes traveled to school may be an appropriate. A few participants suggested using community-level variables, such as the availability of primary school, or using policy changes.

Julia Behrman (Department of Sociology, Northwestern University) described her work, which explored how macro-level (i.e., regional) changes in women’s schooling attainment were associated with micro-level (i.e., household) demographic outcomes. She used DHS data from four countries—Kenya, Malawi, Uganda, and Zimbabwe—to consider the association between regional declines in hypergamy (husbands having more schooling than wives) and demographic outcomes.

Through a multilevel analysis of couples nested in regions, Behrman found that regional declines in hypergamy were associated with increases in intimate partner violence, but there were no associations between regional declines in hypergamy and women’s participation in decision making and control over reproductive health. These results support a backlash

perspective: relative increases in women’s status or educational attainment will lead to a backlash in intrafamily dynamics. This finding demonstrates the importance of considering both the absolute and relative increases in girls’ and women’s schooling, she said.

Mónica Caudillo (Maryland Population Research Center) discussed her research, which considers the effects of school progression relative to age on the timing of family-related transitions, including first sex, union, and pregnancy among women. This work begins with the idea that the average age in a school cohort creates a socially constructed age for all students in that cohort. Thus, Caudillo hypothesized that completing lower secondary (generally 3 years after primary school) can have offsetting effects on the timing of family-related transitions among young-for-grade girls.

Using data from Mexico, Caudillo used month of birth as the instrumental variable for advanced school progression by age. She found that for girls who are young for their grade, having completed lower secondary school increased the likelihood of ever being pregnant, in a union, or having had sex. Potential causal mechanisms are exposure to older peers and finishing academic milestones at an earlier age, which can both act as social signals that girls are ready for the transition to adulthood.

Caudillo’s findings indicate that the socially constructed age within a school cohort has important implications for the transition to adulthood among teenage girls in Mexico. The implication for interventions is that there is a need to protect young-for-grade girls from engaging in risky behaviors and accelerated family-related transitions. In the discussion, Caudillo suggested that, according to this theory, the opposite results may hold for the oldest girls in the classroom, since socially constructed age is a tendency toward the mean age of the cohort in a particular grade.

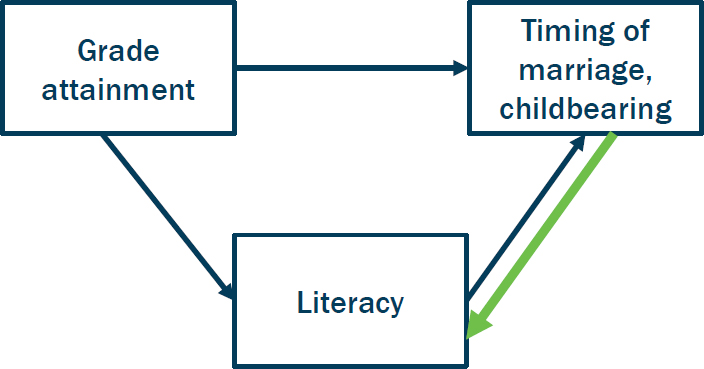

Psaki noted that current research on the links between education and reproductive health outcomes often fails to account for either academic skills (such as literacy), which are assumed to remain constant after school leaving, or the role that reproductive events may have in shaping those skills. That is, just as education may improve reproductive health outcomes, so may experiencing early reproductive events disrupt education, in particular, academic skills: see Figure 3.

Psaki noted that her research used data from two studies—the Malawi Schooling and Adolescent Study and the Adolescent Girls’ Empowerment Program in Zambia—and fixed-effects models that control for stable observed and unobserved characteristics, to study early marriage and childbearing and loss of literacy by adolescent girls in these settings. She found

Source: Presentation by Psaki, Soler-Hampejsek, Mensch, and Amin (2017). Do Early Marriage and Childbearing Cause Loss of Literacy by Adolescent Girls? Comparative analyses from Malawi and Zambia. Workshop on Demographic Effects of Girls’ Education in Developing Countries.

some evidence to support the hypothesis that adolescent girls who gave birth then show a subsequent deterioration in literacy, in comparison with girls who do not give birth.

She noted several implications for education and demographic outcomes. First, there remains a struggle to get girls into primary school and for them to complete primary school. Second, in work on the links between education and demographic outcomes, the assumption that the effects of education will be maintained throughout women’s lives may not hold in all settings. Psaki said her results from both Malawi and Zambia shed light on possible explanations for deteriorations in academic skills after school leaving. Therefore, school dropout by adolescent girls could provide an opportune moment for intervention.

Catalina Herrera Almanza (Economics Department and International Affairs Program, Northeastern University) also took a causal inference approach in her study from Madagascar, which explored early childbearing, school attainment, and cognitive skills.

She used the Madagascar Life Course Transition of Young Adults Survey, a longitudinal dataset that captures the transition from adolescence to adulthood of a cohort aged 21 to 23 in 2012, first interviewed in 2004. To address the endogeneity between education and fertility decisions, she used an instrumental variables approach in which early childbearing is instrumented with the young woman’s community-level access and her exposure to condoms since age 15 after controlling for prefertility socioeconomic conditions. She found that early childbearing has a causal effect on young women’s human capital in Madagascar. Adolescent pregnancy increases the likelihood of dropping out of school and not completing secondary school, thus reducing girls’ cognitive skills, which were measured by mathematics and French test scores. Girls who had a shorter stay in school due to pregnancy had lower cognitive skills. The magnitude of this effect on the test scores was comparable to the effect of having completed secondary school. Herrera-Almanza suggested that policies should both try to prevent early pregnancy and allow teenage mothers to catch up on education to avoid losses in cognitive skills and school attainment.

Letícia Marteleto (Department of Sociology, University of Texas at Austin) also spoke on reverse causality, describing her research on the effects of adolescent childbearing on women’s educational outcomes. She considered whether multiple demographic events or interactions between marital unions and adolescent childbearing create educational disadvantages.

Using the 2013 School-to-Work Transitions Survey carried out in Brazil, Marteleto found that adolescent mothers are disadvantaged in both educational attainment and high school completion. There are negative associations between adolescent childbearing and years of schooling and high school completion. Union formation has a similar negative effect. There is also an interaction effect between adolescent childbearing and union formation on adolescent disadvantage.

Workshop participants discussed the relationship among education, gender, and gender norms. One participant raised the question of whether schooling as an institution actually perpetuates gender disadvantages and non-egalitarian gender dynamics, specifically, whether education is gender retrogressive and whether schools should teach specifically around gender attitudes. This question led to a discussion of whether gender norms should be part of the curricula in schools and broader discussions on what constitutes quality schooling.

THE IMPORTANCE OF QUALITY

Justin Sandefur (Center for Global Development) began a discussion of the global

learning crisis: school quality is lower than it used to be; kids are not learning; and rates of literacy and numeracy continue to be low. His work has explored the effects of school quality on learning outcomes, focusing on effectively measuring both learning and school quality. Possible pathways between schooling and learning outcomes include education quality as a moderator and individual literacy as a mediator between schooling and outcomes.

Sandefur found that there is huge variation in school quality in low- and lower-middle-income countries, and the learning outcome returns from girls’ education partly depends on quality. He also found that school quality is associated with child survival, but noted that the mechanisms are unclear, and there are many factors that affect child survival beyond schooling and literacy. Importantly, he said, there remains a significant direct effect of schooling that is not explained by quality alone.

Many of the workshop participants discussed the pathways between school quality and girls’ learning outcomes. Desai pointed out that the social networks of schools themselves may be part of the mechanisms that lead to improved learning. Sandefur noted that during a time of scarce resources, better educating girls by improving school quality may result in reduced mortality and fertility.

SCHOOL QUALITY AND DEMOGRAPHIC OUTCOMES

Erin Murphy-Graham and Alison Cohen (Graduate School of Education, University of California, Berkeley) discussed using mixed-methods longitudinal work to explore school quality in Honduras. They considered whether different types of schooling have significant effects on demographic outcomes: for example, are marriage and childbirth predictors of dropping out of school and is school quality part of this pathway.

Murphy-Graham and Cohen used data from a comparison of two systems of rural education and a quasi-experiment that matched two different delivery systems of secondary education. Overall, 45 percent of girls had married by age 20, and 46 percent had had children, but the overlap was not perfect: only 32 percent of girls had both had a child and entered into a union. Their results showed that only 8 percent of the girls who got married and 6 percent of girls who became pregnant attained more education after that event. However, the differences in secondary education quality did not appear to have had an effect on early childbearing and unions.

Murphy-Graham and Cohen noted that the lack of a relationship between school quality and girls’ demographic outcomes could be due to the larger forces in society that intersect with girls’ lives. These forces include poverty, a lack of employment, a lack of credit, and limited opportunities for women beyond being a housewife. This environment creates the desire for motherhood, even at an early age. Simply stated, conditions of uncertainty produce motherhood.

Several workshop participants discussed the benefits of additional education in contexts with limited labor market options for women. Sarah Baird (Milken Institute, School of Public Health, George Washington University) said that she has observed similar limitations for women in Malawi. Perhaps, moving forward, education systems should further explore entrepreneurial pathways or skills training to provide direct links between education and employment. To think further about school quality and demographic outcomes, she suggested, researchers would also need to deliberately address gender equality in relationships.

Monica Grant (Department of Sociology. University of Wisconsin–Madison) discussed her research on schooling expansion, free primary education, and the timing of first marriage in Ethiopia, Malawi, and Uganda. She used data from the 2010 DHS from Malawi and the 2011 DHS from

Ethiopia and Uganda and instrumental variables regression models with exposure to free primary education as the instrumental variable. She found that in Ethiopia and Uganda each additional year of schooling reduces early marriage, but in Malawi, there were no effects of schooling on early marriage once the instrumental variable of free primary education was introduced. Grant hypothesized that this result is related to the lack of economic opportunities for women.

PROGRAMS AND POLICIES TO KEEP GIRLS IN SCHOOL

Gretchen Donehower (Center on the Economics and Demography of Aging, University of California, Berkeley) discussed whether girls face a disadvantage in time spent on education in comparison with boys and whether unpaid care work, mainly housework and taking care of younger siblings, plays a part. Her project, Counting Women’s Work, has harmonized time-use studies from 11 countries to compare time spent on various activities by age and gender. Donehower found that in the low- and middle-income countries, girls spent less time on education than boys, including time in school and studying outside of school, and more time on unpaid care work. Though boys did more market work than girls, combining market work and unpaid care work, girls did more total work than boys in every country, starting at the youngest ages at which time-use data were available.

Donehower noted that this early-life specialization in unpaid care work by girls sets them up for future economic disadvantage relative to boys, shaping their human capital toward what are in most countries no-pay or low-pay and less productivity activities. Some participants discussed several mechanisms to address this situation, including providing school-based quality child care; recognizing, reducing, and redistributing unpaid care work; conditional cash transfers; recognizing that child marriage is also a child labor issue; and raising wages for paid care work. Donehower presented data on the consumption of unpaid care work, which allowed workshop participants to see and discuss the significant net time transfers that girls were making to the adults and younger children in their families.

Sarah Baird discussed her research in Zomba, Malawi, which evaluated a randomized controlled trial to test the effects of conditional (on schooling) and unconditional cash transfers for never-married 13-to 22-year-old young women. While the program was ongoing, the conditional cash transfer intervention improved education outcomes—both for girls in school and out of school when the program started. The unconditional cash transfer program—which was only targeted at girls who were in school at baseline—had relatively small effects on education, but they led to large reductions in early marriage and pregnancy. This result was due to the fact that girls in the unconditional cash transfer arm kept the money even if they dropped out of school, showing the potential for cash to be protective.

Baird also found large effects of the conditional cash transfer program on marriage and pregnancy for girls who were out of school at baseline: this outcome resulted from the very large effects on education in this group. For the girls who were not in school at the baseline, the effects were sustained 2 years after the program, but for girls who were in school at the baseline, the effects were transitory and faded out 2 years after the intervention. These results suggest the importance of building some sort of capital if effects of cash transfers are to be sustained after programs end, she noted.

Several workshop participants discussed how the effects of schooling are durable and largely in the scope of marriage and fertility. It was noted that this randomized controlled trial showed little evidence for the effects of education directly on em-

ployment rates, migration, or other direct products of human capital. Psaki asked about incentive programs that are tied to performance or merit; Baird responded that incentive programs that are tied to learning result in positive effects on that particular learning measure.

Barbara Mensch (Population Council) discussed research in three programmatic areas: school-related violence, sanitation facilities at schools, and menstrual hygiene management. She noted that the literature on school-related gender-based violence discusses links with a variety of education-related outcomes, including loss of confidence and self-esteem, impaired mental and physical health, early and unintended pregnancy, depression, aggressive behaviors, inability to concentrate in school and on homework, low school participation, reduced learning, and absenteeism. Mensch indicated that although this kind of violence is assumed to be ubiquitous, there is considerable variability in how it is defined, measured, and assessed.

Moreover, Mensch noted, there is a shortage of rigorous quantitative studies investigating the effect of school-related gender-based violence on educational outcomes. Several observational studies have found negative associations, which rather than indicating a causal relationship between such violence and education, may reflect shared underlying characteristics, such as community violence, resource-poor schools, and inadequately trained teachers and administrators. Mensch commented that when violence is common and takes place at home as well as at school, it is difficult to identify the unique effects of violence at school. Mensch also noted that boys are equally as likely to be victims as girls—indeed, they are more likely to be bullied than girls. Thus, unless a gender difference exists in the effect of school-related violence on education outcomes, it is unlikely to explain any gender differences that might exist in those outcomes. To investigate the effects of school-related gender-based violence on attendance, dropout, and learning, Mensch said, it is important to develop a concise set of validated indicators and to design studies that address the potential endogeneity by either identifying policy shifts that have been effective in reducing school-related gender-based violence or by conducting randomized controlled trials.

Mensch also discussed how poor sanitation in school is purported to affect school attendance and retention of students, particularly girls. Although there is increasing policy emphasis on inadequate school sanitation, reliable and systematic data on water, sanitation, and hygiene (known as WASH) are lacking. Mensch noted that systematic reviews have identified few empirical studies to support assertions that inadequate sanitation facilities are a major cause of girls’ absenteeism and dropping out. A randomized controlled trial in Kenya and a study on latrine construction in India indicate some effects on attendance, but thus far there is no evidence that improved sanitation enhances learning. Mensch suggested that future work on WASH and education should include more intervention studies focused on how the type, privacy, and cleanliness of toilets and the availability of water at school affect absenteeism, retention, and learning outcomes. She also stated a need for studies on both males and females and younger and older students to determine whether adolescent girls are differentially affected by the quantity and quality of sanitation facilities.

Mensch also summarized the research on menstrual hygiene management and educational outcomes, such as absenteeism and learning. She noted that quantitative research on whether menstruation causes absenteeism is inconclusive. She described an ongoing randomized controlled trial by the Population Council that is evaluating a school-based intervention in Kenya that includes both distribution of sanitary pads and reproductive health education.

Overall, Mensch said, although assertions abound regarding the detrimental effects of school-related gender-based violence, WASH, and inadequate menstrual hygiene management on educational outcomes, rigorous quantitative evidence for such effects is limited or nonexistent. She emphasized the need for well-designed impact evaluation studies to inform policies and programs. A few workshop participants discussed the meshing of advocacy and research on these topic areas.

LOOKING TO THE FUTURE

Cynthia Lloyd (independent consultant) reflected on how far the field of girls’ education has come since the publication of the National Academies’ Growing Up Global report (2005). This report was focused on changing transitions to adulthood in developing countries in the context of rapid globalization. In that effort, the authors developed a conceptual framework that identified key factors, including, most importantly, education, that contribute to adolescents’ successful transitions to adulthood: that publication covered transitions to work, marriage, and parenthood, as well as citizenship. Education was defined to include both access to and participation in quality education throughout adolescence.

This workshop on girls’ education in developing contexts builds on that earlier work, using rich longitudinal data that were not available 10 years ago, to explore causal relationships and pathways between educational enrollment, attainment, and quality on the timing of transitions to marriage and parenthood. In future research, she said, even more attention to school quality as a factor in reproductive transitions is needed.

Jere Behrman (University of Pennsylvania) responded that no one really knows what school quality means. He said that researchers and policy makers also need to understand what aspects of certain contexts are transferable to other contexts. Throughout the workshop, participants discussed whether education around gender and gender dynamics should be included as an aspect of quality schooling.

Murphy-Graham noted that there may be a threshold for quality. That is, with very low-quality schooling, the outcome is likely to be very low learning outcomes. However, for middle-level quality, it is difficult to detect a quality effect.

Jere Behrman stressed the need to understand education more broadly than just schooling. Some workshop participants expressed interest in understanding what dimensions of context-specific interventions are critical to consider. Blanc pointed out that in the past the field did not pay much attention to context or what it means to be educated in a certain place at a certain time. Now, she said, there is recognition of a need to understand education and context outside of school.

Murphy-Graham discussed the emergence of a theme around the “dosage” of education, which is particularly salient around the transition to adulthood. She said that future research should consider whether there is a certain “dosage” necessary for a threshold between education and demographic outcomes.

Lloyd noted that learning outcomes are often considered to be intermediate outcomes: the field then leaps forward to demographic and reproductive outcomes. She suggested that for better measures and dimensions of learning, researchers need to rely on the education community.

Kim Wright-Violich (Echidna Giving) and Clio Dintilhac (Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation) noted that their organizations’ focus on girls’ education is because of the demonstrated effects of girls’ education on both learning outcomes and demographic outcomes.

Mensch encouraged workshop participants to consider the effects of education beyond the end of schooling and follow interventions for longer periods of time.

She said that future work should consider life-course and intergenerational trends in education and outcomes. In addition, there might be gains in understanding if research on girls’ education is expanded to a broader gender lens that includes research on boys. Mensch added that research on girls’ education can benefit from the continued use of longitudinal and experimental data to understand mechanisms, along with descriptive work to contextualize the mechanisms between girls’ education and demographic outcomes.

WORKSHOP STEERING COMMITTEE:

ANN K. BLANC (Chair), Population Council; JERE R. BEHRMAN, University of Pennsylvania; CYNTHIA B. LLOYD, Independent Consultant.

DISCLAIMER: This Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief was prepared by Goleen Samari as a factual summary of what occurred at the meeting. The statements made are those of the rapporteur or individual meeting participants and do not necessarily represent the views of all meeting participants; the planning committee; the Committee on Population; or the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The planning committee was responsible only for organizing the workshop, identifying topics, and choosing speakers.

REVIEWERS: To ensure that it meets institutional standards for quality and objectivity, this Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief was reviewed by Ann Biddlecom, International Research, Guttmacher Institute; Ann K. Blanc, Social and Behavioral Science Research, Population Council; Ruth Dixon-Mueller, Independent consultant, Alameda, CA; and Monica J. Grant, Department of Sociology, University of Wisconsin–Madison. Kirsten Sampson Snyder, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, served as review coordinator.

SPONSORS: This workshop was supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation. For additional information regarding the meeting, visit http://nas.edu/EffectsofGirlsEducation.

Suggested citation: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2017). Demographic Effects of Girls’ Education in Developing Countries: Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: https://doi.org/10.17226/24895.

Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education

Copyright 2017 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.