1

Introduction

In 1980, Congress passed the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA), which established the Superfund program to address environmental contamination in the United States. As part of the Superfund program, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) conducts site investigations, determines whether a site needs to be remediated, and attempts to identify parties who are responsible for the contamination and thus financially responsible for the remediation activities. Identifying potentially responsible parties is often difficult because sites can have a long history of use and involve contaminants that have many potential sources. That is often the case for sites that involve metal contamination; metals occur naturally in the environment, they can be contaminants in the wastes generated at or released from a site, and they can be used in consumer products, which can degrade and release the metals into the environment. Lead as an environmental contaminant associated with sites at or near lead-mining districts provides a primary example of the complexities that are involved in identifying potential sources. Lead occurs naturally in the environment, is present in wastes associated with lead-mining districts, and has been used in various consumer products that are known to have resulted in environmental contamination, such as leaded gasoline and paint. Given the complexities surrounding lead contamination, Congress asked EPA to commission a study by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to examine the extent to which various sources contribute to environmental lead contamination at Superfund sites that are near lead-mining areas. Accordingly, the National Academies convened the Committee on Sources of Lead Contamination at or near Superfund Sites, which prepared this report.

SUPERFUND PROGRAM

As noted, the Superfund program was established to address human-health and environmental risks posed by abandoned or uncontrolled hazardous-waste sites. CERCLA gave EPA the resources and authority to clean up sites and seek reimbursement from potentially responsible parties. The Superfund process begins with the identification or notification of a potentially hazardous release and involves several steps, which are described in Box 1-1. If EPA’s investigation results in listing of a site on the National Priorities List (NPL), the site is eligible for cleanup under the Superfund program. As of March 2017, 1,337 sites were listed on the NPL (EPA 2017a). They include manufacturing plants, processing facilities, landfills, and mining sites and involve a wide array of contaminants. Some of the most complex sites are mining sites not only because of their size but because their contaminants can have multiple possible natural and anthropogenic sources; this is problematic when one is trying to identify contaminant sources and assign financial responsibilities for remediation activities. Appendix A provides information on the challenges of obtaining information that can help to determine financial responsibilities.

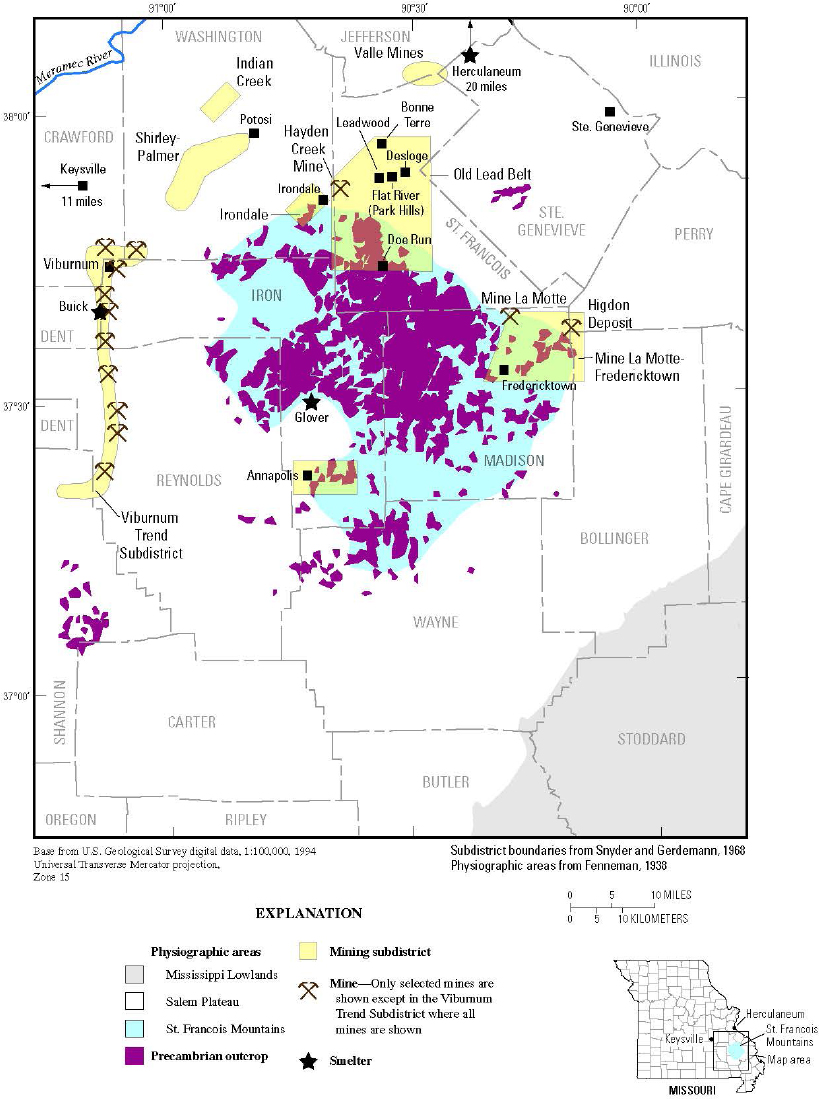

SOUTHEAST MISSOURI LEAD MINING DISTRICT

As noted, mining sites are typically large and complex, and the Southeast Missouri Lead Mining District provides a prime example of the complexities that a site might pose. It is composed of three large subdistricts—the Old Lead Belt, Mine La Motte–Fredericktown, and the Viburnum Trend—and several smaller ones (see Figure 1-1; Seeger 2008).1 The area has a long history of lead mining that began in the early 1700s and continues today (Seeger 2008). Until the 1860s, the majority of mining was accomplished by digging shallow pits and extracting the ore near the surface (Buckley 1909; Seeger 2008). Mining practices changed dramatically in the 1860s; the Saint Joseph Lead Company was formed in 1864, and the diamond drill bit was introduced in 1869 (Bonne Terre

___________________

1 The committee notes that considerable lead was also produced in the Washington County barite district in the same region.

News 2008; Mugel 2017). Those events led to extensive underground mining in the area and the development of a complex of mines in the Old Lead Belt that were 200–300 feet deep and connected by over 250 miles of underground railroad (Seeger 2008). Mines in the Old Lead Belt were finally closed by the early 1970s because the higher-grade ore had been exhausted. At that time, the large and recently discovered deposits of the Viburnum Trend were coming into production (MO DNR 2017). Today, the only active mining in the area is along the Viburnum Trend, from which Missouri continues to supply most of the US primary lead with byproduct zinc, copper, and silver (Guberman 2014).

The mining sites typically included milling operations in which the ore was processed and the lead-bearing minerals were extracted. There were also smelting operations in the area that converted the lead from its mineral form to its elemental state. Waste materials were generated in processing the ore, and in the early years a density separation process was used and generated a coarse waste material often referred to as chat that was accumulated in enormous piles at the milling sites (ATSDR 1996, 1998). In the later years, a finer grinding of the ore allowed a more efficient separation process (flotation) to extract the lead minerals while generating much finer waste mate-

rials, known as tailings, that were pumped into settling ponds or impoundments (ATSDR 1996, 1998). The committee notes that mining waste or residual material from processing is typically referred to as tailings; however, the term chat is also used in the Southeast Missouri Lead Mining District to distinguish between coarse and fine waste material. Mining operations are discussed further in Chapter 2.

Some areas in Southeast Missouri are contaminated with lead, and several areas in St. Francois, Madison, Jefferson, and Washington Counties have been designated as Superfund sites (EPA 2017c). Determining the sources of lead at the sites, however, is complex. First, the area is rich in naturally occurring lead-ore deposits that are at or near the surface. Second, the area has a long history of mining activities. Third, an enormous amount of waste has been produced as a result of all the mining activities. For example, an estimated 250 million tons of tailings were generated from mining activities in the Old Lead Belt (ATSDR 1996, 1998). Some of the tailings have been redistributed from their original disposal sites by natural forces, such as wind and rain, and there has been intentional transport of

chat and other byproducts offsite (ATSDR 1996, 1998). Specifically, the tailings were sold as agricultural lime, used as fill material, incorporated into asphalt, and used to treat roads (Meyers 1989; ATSDR 1996). There are even anecdotal accounts of the tailings being used for children’s sandboxes (Lee 2006). Fourth, the picture is complicated by the long history of use of lead in consumer products, such as paint and gasoline. Thus, lead at a site could result from naturally occurring deposits, from historical mining activities, from current mining activities, from consumer products, or from some combination, and identifying the sources becomes problematic.

THE COMMITTEE AND ITS TASK

The committee that was convened as a result of the agency’s request included experts in aqueous and soil geochemistry, economic geology, environmental fate and transport, lead-source characterization, environmental data analysis, risk assessment, and Superfund policy. Appendix B provides biographic information on the committee members. As noted, the committee was asked to examine the extent to which various sources contribute to environmental lead contamination at Superfund sites that are situated near lead-mining areas and to focus specifically on sources contributing to lead contamination at sites near the Southeast Missouri Lead Mining District. The committee’s verbatim statement of task is provided in Box 1-2; it is important to note that the committee was not asked to identify human exposure pathways.

THE COMMITTEE’S APPROACH TO ITS TASK

To accomplish its task, the committee held five meetings. During its first two meetings, the committee held open sessions to hear from the sponsor, mining-industry representatives, and regional scientists from the US Geological Survey, the Missouri Geological Survey, the Missouri Department of Natural Resources, and the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services. As part of the second meeting, the committee toured portions of the Southeast Missouri Lead Mining District to gain a better appreciation of the natural geology and geography, the mining and tailings sites, and the remediation activities. Appendix C contains the agendas of the open sessions. The committee reviewed numerous scientific publications and all materials submitted to it from outside parties.

The committee interpreted its task as a request for investigative strategies that could provide the evidence needed to identify lead sources in various environmental media. It did not consider its task to be determining lead sources; such an activity would require extensive sampling, analysis, and interpretation that the committee was not equipped to perform. As directed, the committee focused its efforts on whether sources of lead in the Southeast Missouri Lead Mining District could be distinguished by using various analytic techniques. The committee emphasizes that it did not consider exposure pathways, which would need to be considered for identifying which lead sources are contributing to human exposure.

ORGANIZATION OF THIS REPORT

The committee’s report is organized into five chapters and three appendixes. Chapter 2 describes possible sources of lead contamination. Chapter 3 describes mechanisms of environmental dispersal of lead, and Chapter 4 proposes investigative strategies for determining sources of lead in various media. Chapter 5 discusses the implications of the committee’s strategies specifically for the

Southeast Missouri Lead Mining District and describes the research needed for identifying lead sources at Superfund sites associated with mining activities. Appendix A provides information on the challenges of obtaining information on lead sources, Appendix B provides biographic information on the committee, and Appendix C contains the agendas of its open sessions.

REFERENCES

ATSDR (Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry). 1996. Preliminary Public Health Assessment, Big River Mine Tailings Desloge (a/k/a St. Joe Minerals), Desloge, St. Francois County, MO. CERCLIS No. MOD 981126899 [online]. Available: http://health.mo.gov/living/environment/hazsubstancesites/pdf/bigriverminetailings.pdf [accessed June 28, 2017].

ATSDR. 1998. Big River Mine Tailings Superfund Site, Lead Exposure Study, St. Francois County, Missouri [online]. Available: http://health.mo.gov/living/environment/hazsubstancesites/pdf/BRMTLeadExposureStudy98.pdf [accessed June 28, 2017].

Bonne Terre News. 2008. Retrospect on St. Francois County Mining. Pp. 150-151 Chat Dumps of the Missouri Lead Belt, St. Francois County. Adrian, MI: R.E. McHenry.

Buckley, E.R. 1909. Geology of the Disseminated Lead Deposits of St. Francois and Washington Counties, Vol. IX, Part I. Jefferson City, MO: H. Stephens Printing.

EPA (US Environmental Protection Agency). 2017a. Superfund: National Priorities List (NPL) [online]. Available: https://www.epa.gov/superfund/superfund-national-priorities-list-npl [accessed March 10, 2017].

EPA. 2017b. Superfund Cleanup Process [online]. Available: https://www.epa.gov/superfund/superfund-cleanup-process [accessed March 10, 2017].

EPA. 2017c. Search for Superfund Sites Where You Live [online]. Available: https://www.epa.gov/superfund/search-superfund-sites-where-you-live [accessed July 12, 2017].

Guberman, D.E. 2014. Lead. Pp. 90 in Minerals Yearbook: Vol. 1. Metals and Minerals. U.S. Geological Survey [online]. Available: https://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/lead/mcs-2014-lead.pdf [accessed June 28, 2017].

Lee, M. 2006. Symbols of pride. P. XV in Chat Dumps of the Missouri Lead Belt, St. Francois County, 2008. Adrian, MI: R.E. McHenry.

Meyers, H. 1989. Where Did All the Tailings Go? Pp. XI-XII in Chat Dumps of the Missouri Lead Belt, St. Francois County, 2008. Adrian, MI: R.E. McHenry.

MO DNR (Missouri Department of Natural Resources). 2017. Missouri Lead Mining History by County. Missouri Department of Natural Resources [online]. Available: https://dnr.mo.gov/env/hwp/sfund/lead-mo-historymore.htm [accessed February 15, 2017].

Mugel, D.N. 2017. Geology and Mining History of the Southeast Missouri Barite District and the Valles Mines, Washington, Jefferson, and St. Francois Counties, Missouri. Scientific Investigations Report 2016-5173. Reston, VA: U.S. Geological Survey [online]. Available: https://pubs.usgs.gov/sir/2016/5173/sir20165173.pdf [accessed June 28, 2017].

Seeger, C.M. 2008. History of mining in the Southeast Missouri Lead District and description of mine processes, regulatory controls, environmental effects, and mine facilities in the Viburnum Trend Subdistrict. Pp. 1-34 in Hydrologic Investigations Concerning Lead Mining Issues in Southeastern Missouri, M.J. Kleeschulte, ed. Scientific Investigations Report 2008-5140. Reston, VA: U.S. Geological Survey [online]. Available: https://pubs.usgs.gov/sir/2008/5140/pdf/SIR2008-5140.pdf [accessed June 28, 2017].