7

Teacher Development in the United States: Collaborative Approaches

Discussions of teacher development in the United States began with an overview of the context and some issues and challenges. Presenters described several programs that allow teachers to collaborate with their peers. Participants also had the opportunity to discuss some of the differences between the U.S. and Finnish approaches to teacher professional development.

OVERVIEW OF PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT

Mary Kay Stein of the University of Pittsburgh offered an overview of the ways teachers may experience professional development in the United States. She began with her perspective on what teachers need to gain from professional development. Stein described her ideal vision for mathematics teaching. The student-centered model has become popular in the United States because it has been a useful tool for challenging what has become the “modal form of mathematics instruction”: a class full of students sitting in rows listening to the teacher and doing individual work. Researchers and practitioners use the student-centered model to depict a more dynamic relationship in which teachers “mediate interactions among students and between students and the content they are studying.” These interactions form what is called the “instructional triangle.” The model is student centered rather than teacher centered; the teacher listens, interprets, and responds to students’ current understanding to help them move toward the learning goal.

This is an ambitious vision, Stein acknowledged. It is a much more complex way of teaching than the traditional approach, and in her view the majority of U.S. teachers do not teach in a way that aligns with this vision. She also believes that the preservice education most teachers receive, whether in 1 year or 5 years, is not adequate to prepare them to teach in the a dynamic and student-centered way. Ideally, the role of professional development is to help teachers move toward this vision. This view of professional development is in line with the idea that continuously learning throughout one’s career is a critical aspect of being a teacher.

At present, however, professional development for U.S. teachers is “a patchwork of opportunities” that may be formally planned and required, or may be neither. Professional development is often delivered in half-day or full-day workshops planned by districts or offered during the summer or on weekends. These experiences tend to be very abbreviated, though they are linked across an opportunity or several opportunities. Some teachers pursue master’s-degree coursework while continuing to teach. Some pursue learning opportunities through professional organizations, such as the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. Of course, teachers learn all the time through their daily work, especially through interactions with their colleagues. However, given the typical setup of schools nowadays, this interaction is not encouraged.

These experiences rarely add up to a coherent program of study: they are beneficial but “not transformative.” This patchwork approach to teacher development is the root cause of many problems. Well-intended teachers implement what they learn through these opportunities. However, according to Stein, teachers “teach as they have been taught.” Professional development courses or workshops that are themselves taught in traditional ways do not result in significant changes to classroom teaching, even if their objectives align with the student-centered vision. Principals and coaches1 or mentors, who might be expected to guide and support teachers, often lack the experience or expertise to reinforce the professional development teachers have received.

Moreover, teachers are not generally held accountable for applying what they have learned from professional development. The providers of professional development are not generally individuals who have administrative authority over teachers, and rarely is there a mechanism for follow-up

___________________

1 A coach is a certified teacher that works with classroom teachers and assists them in implementing new instructional techniques, courses, and a curriculum if necessary.

on how well teachers incorporate what they have learned into their practice. At the same time, the teaching practices promoted through professional development often do not align well with the demands of high-stakes assessments, or with the criteria used in teacher evaluation systems. The stakes associated with both, student assessment and teacher evaluation, put considerable pressure on teachers; therefore it may be difficult for them to respond to professional development that does not align with those imperatives.

Stein closed with some ways professional development can be more effective. In her view, the most effective approaches

- are planned at a large scale rather than as small, “boutique” programs;

- address communities of teachers rather than teachers as individuals;

- are ongoing rather than taking place in “one-shot” workshops;

- engage teachers in active rather than in passive learning; and

- are based primarily in practice rather than in theory, using students’ work, and videos of instruction.

COLLABORATIVE APPROACHES

Five presenters described ways U.S. mathematics teachers learn and collaborate. Kara Jackson of the University of Washington, Seattle, explained that the presenters had selected examples to highlight promising areas that cut across different contexts and to identify any aspects that may be unique to the United States.

Jackson shared several perspectives on teacher learning. One is that professional learning for teachers is a continuum. This is particularly important because “more than small tweaks” are needed to help U.S. teachers shift to a focus on student-centered learning. Bringing this change will require them to develop their content knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge, as well as make changes in their classroom practice. At the same time, the pool of U.S. teachers is diverse: they vary in their preparation, the experiences they bring to their work, and the schools and contexts in which they teach. Meeting their professional development needs requires flexibility.

Jackson also pointed out that research on in-service professional development in the United States has been shown to have a minimal impact on teachers’ practice. She suggested several possible reasons:

- Teachers need significant development in mathematics content knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge.

- Schools and districts may constrain the content of professional development courses or fail to meet the actual needs of their teachers.

- School and district settings mediate the impact of professional development on teachers’ practice; for example, school leaders may communicate instructional expectations that are at odds with the content training teachers have received.

- There is a long-standing tradition of privacy among U.S. teachers, who tend to work alone behind a closed classroom door.

- Logistical challenges and limited resources may constrain the time teachers are able to spend on professional development.

The five approaches discussed in the next section hold promise addressing some of these challenges, Jackson explained.

Lesson Study

Aki Murata of the University of Florida focused on how school-based teams of prospective teachers can provide professional development. Typically, this approach is carried out by small groups of teachers working together on grade-level or subject-matter issues. These groups may help one another build their capacity to address specific issues, such as preparing for testing, restructuring programs within the school, or implementing a new curriculum. They may also work together to address broader educational issues, for example, exploring ways to integrate new standards into their everyday practice. Groups also help teachers build and nurture a professional community.

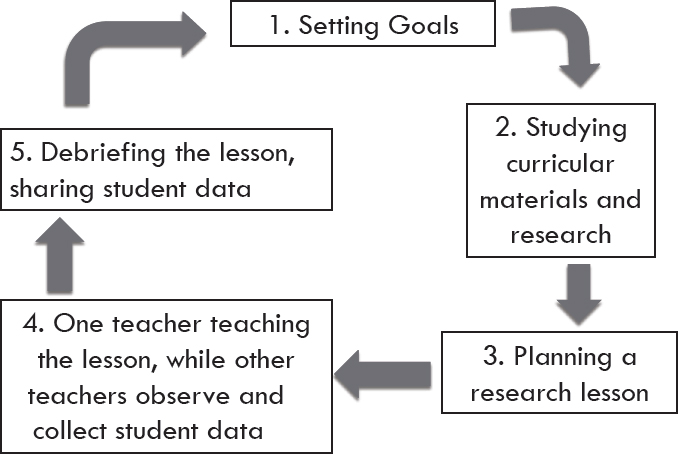

Murata described an example of how a group might collaborate in lesson study—a research process that teachers do together. Lesson study is very common in Japan, but it is done somewhat differently in the United States. The process begins with the identification of a topic the teachers want to explore, such as how students learn about fractions. They develop a lesson plan related to the chosen topic, paying attention to every detail of the lesson, observe the lesson being taught by one member of the group, and refine the lesson based on the data they collected (see Figure 7-1). This process may be repeated several times using strategies they have discussed. Lesson study, however, is not about creating a library of perfect lessons—it is a learning process for teachers.

SOURCE: Aki Murata, University of Florida, workshop presentation.

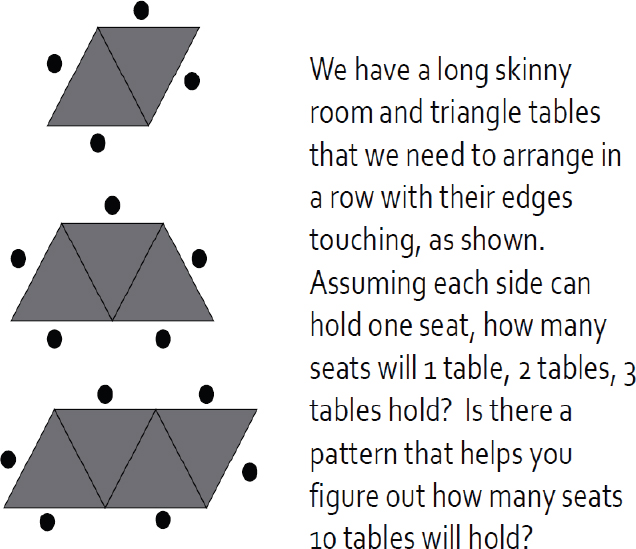

Murata showed a video of elementary and middle school teachers engaged in a lesson study related to a beginning algebra problem. The teachers planned the lesson, based on the problem shown in Figure 7-2, and then it was taught twice by different members of the group. In the first enactment of the lesson, the teacher gave students a worksheet that provided a structure for their responses, but after that experience they decided it might be more effective to provide less structure. In the second enactment of the lesson, the teacher gave the students random numbers for the table and asked the students to figure out how many seats were around each. In the discussion the teachers had afterward (shown in the video), they identified specific differences and why they decided the second approach was more effective.

Florida adopted lesson study as a statewide professional development approach in 2010. The state received a large federal grant to support this initiative, and Murata along with several colleagues conducted research on the project. Teachers reported that they enjoy the opportunity to work together and that they recognize the relevance of what they learn through lesson study to their own classroom practice. School and district administrators “are coming up with new kinds of supports so teachers can keep doing this.” The local officials hope to “take ownership” of the approach.

SOURCE: Aki Murata, University of Florida, workshop presentation.

Murata and her colleagues have also identified challenges. For example, though lesson study is intended to challenge teachers’ thinking in positive ways, it may instead reinforce their existing beliefs. It is not easy for many teachers to speak candidly about their colleagues’ work, and she suggested that a mechanism for bringing in new ideas is needed to help teachers challenge one another.

Murata closed with the observation that lesson study might be a way to meet key goals for professional development identified in a research brief by the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics.2 Those goals are that professional development should build

___________________

2 Mathematics Professional Development. Professional Development Research Brief. NCTM. November 19, 2010. This document was among the background readings made available to participants before the workshop and is available at http://sites.nationalacademies.org/cs/groups/pgasite/documents/webpage/pga_173341.pdf.

- teachers’ mathematical knowledge and their capacity to use it in practice;

- teachers’ capacity to notice, analyze, and respond to students’ thinking;

- teachers’ productive habits of mind; and

- collegial relationships and structures that support continued learning (NCTM, 2010).

Lesson study is particularly effective at building relationships and supporting continued learning, she concluded.

Texas Regional Collaboratives for Excellence in Science and Mathematics Teaching

Debbie Plowman of the University of Texas in Austin described the Texas Regional Collaboratives, a network of partners from schools and universities throughout the state that provide professional development for science and mathematics teachers from preschool through secondary education.3 Texas has 43,000 teachers, more than 1,266 school districts, and 9,225 schools. The Texas Regional Collaboratives are federally funded, and in the 2016–2017 school year, they sponsored 29 projects, serving 870 teachers, and reaching 80 percent of Texas districts.

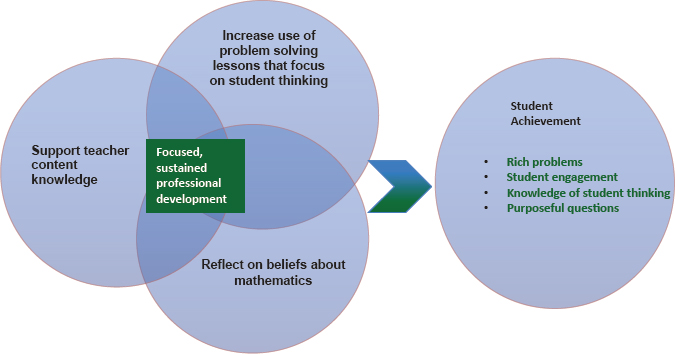

The partnerships are structured to pursue shared goals. Figure 7-3 illustrates the theory of action that guides the networks in Texas. Guidelines help to bring consistency across the networks. For example, each network must include a mathematician in program planning, and partners are expected to participate frequently in statewide conferences and other activities. The networks focus on developing teachers’ content knowledge and improving instructional practices. Participating teachers are encouraged through reflection and structured teaching exercises to focus on their students’ thinking, Plowman explained.

Plowman also pointed out several key benefits of teachers’ networks. She noted that they allow teachers to look outside of their school or region for learning opportunities not available locally, which is particularly useful in rural areas that may have relatively few educational resources. Those educators who participate can grow as teacher leaders who bring new ideas back to their schools. These are not just “one-shot workshops.” The net-

___________________

3 See http://www.thetrc.org/about-the-trc/ [accessed November 1, 2016] for more information.

SOURCE: Debbie Plowman, University of Texas, workshop presentation.

works provide follow-up and foster long-term relationships that can have a lasting impact on teachers.

Math Teacher Circles

Another structure for collaborative teacher learning used in the United States is based on the idea of math circles, communities of students who work with mathematics professors on engaging problems. Katie Hendrickson of Code.org explained that teachers, observing the benefits of math circles for students, wanted to work together in engaging problems as well. The first math circle in the United States was founded in 2006, and a decade later there are now 200 math teacher circle sites in 40 states.4 This is a grassroots endeavor, Hendrickson explained. Teachers interested in starting a math circle attend a training session with a national organization, and receive ongoing support as they build their own circle.

Typically, a mathematics teacher circle organizes a week-long summer workshop that includes problem-solving sessions. During the school year, the group might meet monthly for a 3-hour session to work on a problem. Usually, the problem will be one with a “low entry point,” so that elementary and secondary teachers and mathematicians can all work

___________________

4 See http://www.mathteacherscircle.org/about/history/ [accessed November 1, 2016].

together on the problem, using the skills and knowledge they bring to the workplace. After working in pairs and small groups, the circle discusses the problem-solving processes rather than the solution.

One goal for mathematics teacher circles is to increase participants’ mathematics knowledge, and another is to help them facilitate the same sort of problem-solving technique with their own students. The circles also develop a community of “doers of math” and give teachers a chance to be with other people who enjoy mathematics. Emerging research suggests that participation in math circles helps teachers become more comfortable with the idea that everyone struggles with mathematics sometimes and that the struggle is part of the experience. Bringing this perspective to their students is a key benefit, Hendrickson suggested.

Because these are grassroots efforts, they vary significantly, which makes it difficult to trace their effects. The math teacher circles are often started by a small group of teachers and are difficult to sustain over time because of the lack of resources. Nevertheless, there are more circles every year.

The Teacher Leadership Program of the Park City Mathematics Institute (PCMI)

A three-week summer residential program in Utah sponsored by the Institute for Advanced Study, described by Gail Burrill of Michigan State University, is a professional development experience that builds teacher leaders and provides them with a nationwide network of colleagues who become resources for one another.5 This is almost like a “math camp,” she explained, where mathematicians, researchers, undergraduates, graduate students, and K–12 teachers meet in a common space to pursue their own particular program with some shared activities. One component of the larger program is the Teacher Leadership Program, which is designed to help teachers deepen their content knowledge, engage them in reflecting on their instructional practice, and help them become a resource for their colleagues.

The Teacher Leadership Program provides a mathematics course consisting of a series of carefully sequenced problems that have multiple entry points and culminate in a profound mathematical conclusion, usually an advanced concept unfamiliar to teachers. In the second daily session, teachers delve into and reflect on an aspect of practice, such as the role of formative

___________________

5 See http://mathforum.org/pcmi/ and https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCx593kvk9NcwtCIjxXqZkrg [accessed November 1, 2016] for more information.

assessment in teaching, and learning mathematics using artifacts of practice, such as videos or student work, to ground their thinking. In the afternoons the teachers work with several peers to design professional development activities to use with their colleagues in their local schools and districts. These include engaging in a lesson study, developing rubrics for evaluating student use of the Common Core State Standards mathematical practices, or researching benchmark tasks that can be used to introduce a mathematical topic. Participants also interact with those from the other PCMI programs in activities, such as learning about math circles, participating in pizza and problem-solving sessions, listening to and discussing lectures from internationally recognized mathematicians, or sharing favorite teaching practices.

The program in its current state began in 2001 with approximately 60 teachers participating every year in a summer program. Over time, the excitement and energy of the program and being able to discuss teaching with others across the nation has resulted in a wide network of “PCMI teachers.” “PCMI teachers are taking charge of their own learning,” Burrill observed. She went on to note that PCMI teachers are not always receptive or may not find traditional professional development offerings useful, and they are creating new ways of learning to grow as teachers through the use of social media, a movement that the mathematics education community should attend to and study. Burrill claimed it is important for the field to understand how these interactions work, how they impact teacher practices, and what role, if any, some of the more traditional mechanisms for professional development can play.

Coordinating Professional Development Across a School District

Each of these examples operates independently, noted Kara Jackson. They are available to teachers, schools, and districts around the country, but they are not specifically coordinated with the educational goals of districts or states. Researchers have explored what would be needed for a district to coordinate its professional development offerings. She described a study of four large urban school districts that serve approximately 360,000 students, the Middle School Mathematics and the Institutional Setting of Teaching. In this study, which began in 2007, researchers investigated the instructional improvement efforts of middle school mathematics teachers.6

___________________

6 See http://peabody.vanderbilt.edu/departments/tl/teaching_and_learning_research/mist/ [accessed February 1, 2017] for more information.

Each of the districts studied supported the inquiry-oriented instruction that Jackson described at the beginning of the session, and their support included curricula and professional development for teachers and school leaders. The four districts faced many of the challenges typical of large urban districts: high teacher turnover, large numbers of students performing at low levels in mathematics, and limited financial resources.

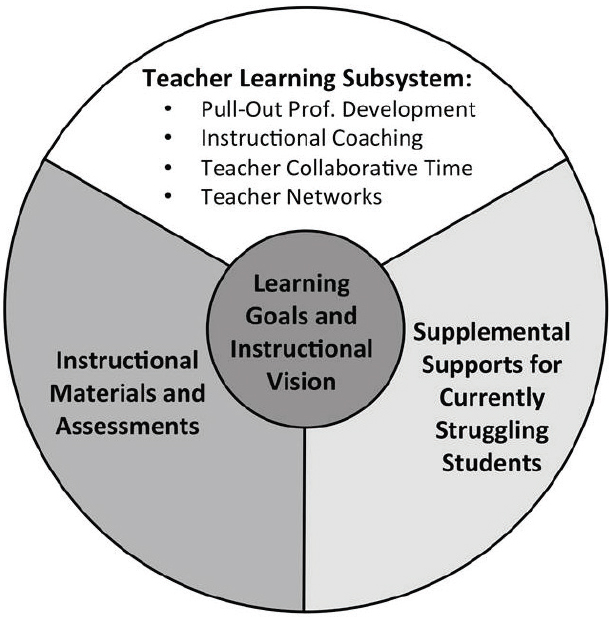

Researchers studied all four districts for 4 years and then worked closely with two of them for an additional 4 years to design instructional support that could be used on a districtwide scale. Researchers developed a theory of action—consisting of goals for instructional improvement and strategies for meeting them—to characterize the approach that they found to be effective. The core of the theoretical approach is a model for an instructional system that is coherent, as shown in Figure 7-4. This diagram shows how the different components of the instructional system can work together to promote research-based ideas about what makes instruction most effective.

SOURCE: Kara Jackson, University of Washington, Seattle, workshop presentation.

As this diagram shows, key components that affect teachers’ practice, including instructional materials and assessment, as well as the kinds of supports struggling students receive, should be coordinated with the training and guidance teachers receive, including the input of school leaders and instructional coaches. It is critical that teachers receive consistent guidance not only within their schools but also across different contexts throughout the district.

DISCUSSION

A closing discussion focused on similarities and differences between Finland and the United States in their professional development opportunities for teachers. Several participants noted the variety of options available in the United States. One commented that the United States has a “leadership model.” That is, because there is little coordination among the avenues for professional learning, coordination becomes the responsibility of teacher leaders to “manage this chaotic environment” and help other teachers learn what instruments they need to make changes in their instruction. High rates of teacher turnover, especially in high-needs schools, mean that many schools may lack experienced teacher leaders, another participant pointed out. Common planning time is not particularly effective, this participant suggested, unless there is an expert leader to shape the discussion. Another participant noted that the U.S. education system struggles with coherence in a more general way—and professional development just reflects that problem.

Regarding Finland, a participant suggested that the situation is not noticeably more coordinated in the Scandinavian nation. Many teachers and schools in both countries seem to turn inward and develop their own vision of what is most effective, a participant commented, because neither nation has a well-articulated shared vision of high-quality instruction. Another participant, however, pointed to teacher preparation as the source of a primary difference between the two nations. Because Finnish teachers are required to study and conduct research while earning their degrees and more years of study are required in preservice, they develop a research-based theoretical framework that guides them after they leave college. While one participant argued that the research-based preparation equips Finnish prospective teachers teaching students to be critical learners, another argued that the research component has been diluted in recent years.