Malcolm Cox of the University of Pennsylvania introduced the speakers for the session, noting that accrediting bodies “walk a tightrope” between a primary responsibility for the health of the public and a responsibility to the profession itself. Cox said that professional development is in transition, and accrediting and credentialing bodies have an important role to play in this transition. In reflecting on the evolution of continuing professional development (CPD) in developed countries, he commented on how professional development has become more results or outcome-oriented, paralleling changes in accreditation and regulation. This is a shift away from the traditional continuing education (CE) measurement method of counting how many hours a professional sat in a session. Cox noted that accrediting and credentialing bodies should be in the forefront of “pushing, pulling, and dragging” the profession forward into the new model of competency-based, high-value CPD, and invited the presenters to share their perspectives on their work.

AMERICAN OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY ASSOCIATION

Neil Harvison, American Occupational Therapy Association

Occupational therapy (OT) is one of the “smaller professions,” said Harvison, chief academic and scientific affairs officer with the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA). For this reason, AOTA is responsible for many of the stages of the learning and credentialing continuum for occupational therapists. The association accredits graduate programs and residencies, provides board and specialty credentials, and offers CE for professionals. For most of these three areas, AOTA has moved to a competency-based system of assessment. Harvison noted that CE for OT remains knowledge based, in part because there are 52 different jurisdictions that dictate the CE requirements for renewal of license or certification.

The movement toward competency-based assessments is based on three broad agreements within the OT community, said Harvison. First, knowledge-based assessments do not guarantee practice competency and quality OT interventions. Second, competency-based learning outcomes are the best way to reflect the effect and value of continuing professional development. Third, competency-based learning outcomes should be consistent with the profession’s quality initiatives and support systems outcomes. However, while there is agreement on these points, he added, there is disagreement on other issues regarding competency-based assessments. The field is struggling to identify the specific outcomes that are reflective of competency, as well as deciding how to best assess these outcomes. Harvison noted that, although perhaps the “gold standard” would be a content expert assessing the competency of each individual, this model is logistically and financially

problematic. Finally, there is the matter of determining what a competency-based system will cost and whether the return on investment will outweigh the cost.

Harvison gave a real-life example of the work that AOTA is undertaking to identify the specific competencies that occupational therapists should have. A recent intervention called Community Aging in Place—Advancing Better Living for Elders (CAPABLE) had great success in using an interprofessional team to help low-income older adults live more easily and safely in their homes (Szanton et al., 2016). A 5-month demonstration project of CAPABLE found that 75 percent of participants had improved their performance of activities of daily living, along with a reduction in depressive symptoms. AOTA took this success story and attempted to identify the “distinct clinical competencies of an occupational therapist that contributed to this positive outcome.” Harvison said that, through this process, the competency that was identified as most important to the success of the program was the occupational therapist’s skill at developing an occupational profile. An occupational profile is an assessment of the individual’s history, experiences, patterns of daily living, interests, values, and needs. Most crucially, the occupational therapist develops an occupational profile in order to identify the daily activities that are most meaningful to the individual but that the individual is unable to participate in successfully.

AMERICAN NURSES CREDENTIALING CENTER

Kathy Chappell, American Nurses Credentialing Center

Chappell is the senior vice president for Accreditation, Certification, Measurement, and the Institute for Credentialing Research at the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC). She started with a question for those who had planned the workshop: “If time were completely irrelevant,” she asked, “how would you have assessed . . . learning and change through this workshop?” She noted that credits for CE have traditionally been awarded based on time (e.g., credit hours), and that such a system has its benefits. It is easily understood, consistent internationally, finite, and equitable. Despite these benefits, the amount of time spent in a CE session is “relatively meaningless” in terms of whether knowledge or skills have been improved, said Chappell. The ANCC sought to use a different approach and developed an outcome-based system for its professional education programs. The new system is a five-tiered model that measures different outcomes at each level:

Level 1: Articulate knowledge and/or skills.

Level 2: Apply knowledge and skills.

Level 3: Demonstrate in an educational setting.

Level 4: Integrate into practice.

Level 5: Measure impact on practice, patient, and/or system outcomes.

There are currently five organizations that are testing this model in practice: American Nurses Association Center for Continuing Education and Professional Development, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Nursing Continuing Education Council, Montana Nurses Association, OnCourse Learning, and Versant. Each of these organizations has been charged with developing, implementing, and evaluating up to three activities using this model, with at least one activity at Level 3 or higher. Chappell noted that before rolling out the new model, ANCC confirmed that its own Commission on Certification would accept this new method of awarding CE credit for ANCC-certified nurses since the current model still uses a credit hours system. Chappell said that if a CE program is “using a currency that is not recognized, there is little incentive for a nurse to participate.” In addition, ANCC worked to translate the conceptual model into practice by developing operational guidelines to help the organizations “figure out how they are actually going to do this.”

Chappell reflected on the lessons learned from ANCC’s experience so far. She noted that some organizations are capable of using an outcomes-based model, while it is “a huge stretch” for others. Similarly, some learners embrace the model, while others “want to sit back and . . . do not want to be engaged in this kind of work.” Chappell said that while some found the model to be “logistically complex to operationalize,” they also found it “liberating not to have to calculate CE hours.” Finally, ANCC found that the concept of getting credit for workplace learning was “very positively received.” By taking CPD out of the classroom and decoupling it from time requirements, the new model allows professionals to advance their learning and skills in a real-world setting and to see a direct effect on their practice.

SCOTTISH EXEMPLAR OF HIGH-VALUE CPD

David Benton, National Council of State Boards of Nursing

Benton, chief executive officer at the National Council of State Boards of Nursing, told workshop participants about his experience working in Scotland for a major integrated health system. The organization was large, with 8,500 nurses spread over multiple sites ranging from rural island communities to major towns. Unfortunately, it was not functioning well as an entity, said Benton. To address the dysfunction, the organization sought to bring about behavior change among its staff through a novel CE strategy. Using a 1995 literature review by Francke et al., the team based its model

on several concepts drawn out by the authors about the role of CE in creating behavior change. These concepts involved

- having a conceptual model to assess impacts,

- identifying strong evidence between experience and behavior change,

- bringing about behavior change through voluntary rather than mandatory participation,

- encouraging risk taking and innovators who are more likely to apply and implement learning,

- focusing on a single topic that builds throughout the experience rather than a potpourri of activities, and

- taking a systems rather than an individual approach.

The team started with a kickoff event to identify the major issues that the nursing staff were currently facing, and then used these findings to drive a series of consequent events. For each event or intervention that was implemented, the team attempted to “assess whether or not that intervention had made a major change” to the services offered by the organization. The team asked staff members to list the biggest problems they were facing, as well as the solutions they had tried. When aggregated, it became clear that the solutions far outweighed the problems, but the solutions had been “locked in different parts of the organization and people were not communicating.” To address this issue of the connections and communication between staff, the team used “social network analysis to identify where individuals get their information from and who they transmit it to.” These communication patterns were then measured. As a result of this analysis and subsequent interventions, communications within the health care system were greatly improved, and isolated domains came together into an integrated system. In addition, the team was able to identify key individuals who were particularly connected and could help disseminate and gather information on the ground.

Workload was identified by staff as the most pressing problem, so the team focused on implementing greater flexibility within the system. These new practices included setting flexible work terms for current and new staff, inviting experienced professionals who had taken a career break to come back into the system and serve their communities, and allowing nurses to take sabbaticals to gain experience in other countries and systems. These new practices resulted in a reduction of the vacancy rate by 55 percent and a reduction in the usage of temporary workers by 73 percent. In addition to these quantifiable benefits, the organization underwent a culture change in which staff were empowered to tackle issues and share experiences, and this culture change spread throughout the rest of Scotland’s health system.

SOURCE: Presented by David Benton, April 7, 2017.

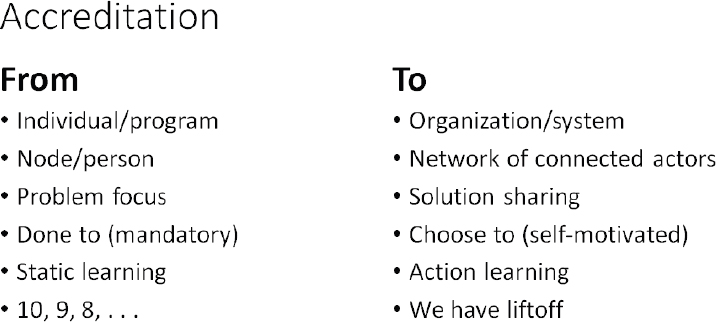

Benton felt strongly that the accreditation processes must undergo a paradigm shift toward “next-generation accreditation” (see Figure 5-1). The focus would not be on individuals, but on the system as a whole, made up of a network of connected actors. It would be geared toward solutions and action, and be driven by self-motivation rather than imposed from above. Finally, it would look at CPD in terms of the return on investment over a period of time, and how CPD can affect the delivery of health care.

LEVERAGING THE POWER OF LEARNING

Kate Regnier, Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education

Regnier is the executive vice president at the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME). She began by outlining the ACCME system, which includes 2,000 accredited organizations that plan and present about 150,000 continuing medical education (CME) programs per year. Together, these organizations interact with around 14 million physician learners and 11 million other learners, which is “an incredible number of touch points with health care professionals.” Regnier noted that since 2006, ACCME has “moved beyond knowledge” for its CME standards. She said “It is no longer acceptable for [CME] to be . . . evaluated for change simply in knowledge.” CME must be geared toward improving a health professional’s actions. To receive ACCME accreditation, CME programs are expected be

- designed to change competence, performance, and/or patient outcomes;

- based on practice-relevant, valid content;

- independent of commercial influence; and

- evaluated for changes in competence, performance, and/or patient outcomes.

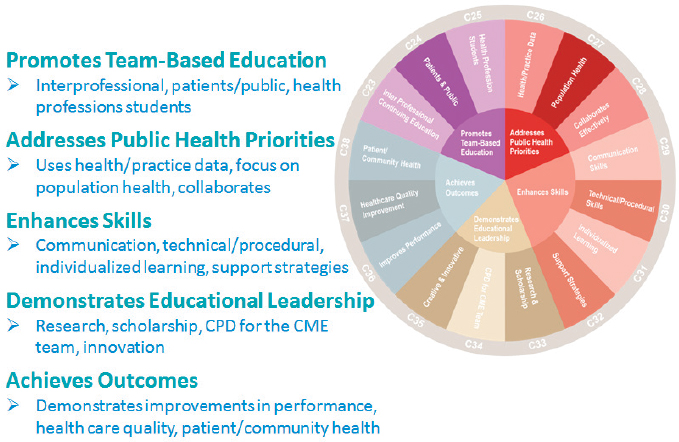

In addition to these basic requirements, ACCME recently announced new commendation criteria (see Figure 5-2). ACCME developed these as a system of “incentives and rewards” to encourage CME providers to offer educational programs with the highest impact. These criteria are optional for accredited CME providers, but providers that demonstrate compliance with 8 of the 16 criteria are eligible for Accreditation with Commendation (ACCME, 2016). The 16 criteria are divided into five categories:

- Promotes team-based education

- Addresses public health priorities

- Enhances skills

- Demonstrates educational leadership

- Achieves outcomes

NOTE: CME = continuing medical education; CPD = continuing professional development.

SOURCE: Presented by Kate Regnier, April 6, 2017. Used with permission from ACCME.

Regnier mentioned that the president and chief executive officer (CEO) of ACCME, Graham McMahon, recently published an article in Academic Medicine: “The Leadership Case for Investing in Continuing Professional Development” (McMahon, 2017). In this article, said Regnier, McMahon makes the business case for accredited CME by arguing that CME

- is a cost-effective, powerful catalyst for change;

- creates and supports teams;

- improves clinician well-being;

- engages clinicians with institutional priorities;

- facilitates processes to empower clinicians in bottom-up quality improvement;

- improves referrals to appropriate, necessary treatment options;

- engages patients and teams in care decision making; and

- improves quality and safety.

As examples of the demonstrable benefits of CME, Regnier shared some real-life outcomes of CME programs offered by accredited providers. In one example, an accredited health system developed an initiative to provide resources and CME activities that address effective communication with patients and peers. This demonstrated an increase in patient satisfaction and involvement in care decisions. In another example, an accredited hospital significantly lowered the rate of complications and improved outcomes for maternal and neonatal patients by integrating emergency drills, simulation exercises, and reminders into existing quality improvement efforts. For the third example, Regnier described a statewide initiative that included partners in community health, community government, health care, and the school system. The initiative focused on clinicians and public education about the risks associated with opioid use. A noteworthy finding was lower rates of deaths from accidental opioid overdose recorded in the first 18 months of the project.

DISCUSSION

Cox thanked the presenters for their perspectives, and noted that accrediting and credentialing bodies have a unique power to catalyze change in the field of CPD, and to “move [CPD] down the track.” He asked workshop participants for their questions and comments.

Interprofessional Education and Team Outcomes

Barbara Brandt, director of the National Center for Interprofessional Practice and Education, began the discussion by saying that the National Center has “struggled with the issue of which model to choose . . . for measuring the impact of interprofessional education on collaborative practice and patient outcomes.” Because health care is shifting toward a team-based approach, CPD should also aim to improve and assess competency at both an individual level and a team level. The issue, said Brandt, is “how to tease” apart these competencies and assess them accurately. She noted that sometimes, one member of the team (often the physician) gets credit for an outcome, simply because it is so difficult to identify and measure team competencies. Brandt said that while this issue has not been resolved, the “conversations are starting to happen.”

Chappell added that jointly accredited providers “do not generally struggle” with planning and implementing team-based interprofessional educational activities, but they do struggle with the evaluation of this type of CPD. She said that common activity evaluations do not reflect the team component. She offered an example where participants are asked to rate their agreement with the statement, “As a result of participating in this educational activity, I will change the way I take care of patients with hypertension.” An evaluation statement that could better reflect the team approach might instead say, “I better understand my role as a member of a team taking care of patients with hypertension.” Chappell commented on the growing body of evidence that interprofessional education is improving team collaboration and patient care. She pointed specifically to a 2016 report from the Joint Accreditation Leadership Summit that shared success stories demonstrating the effect of interprofessional educational efforts (JAICE, 2016). Harvison suggested learning from examples coming out of other health care fields, such as rehabilitation. The field of rehabilitation has been using team-based approaches for more than 50 years and measures the competencies of the team in producing an outcome, he pointed out.

Regnier added that ACCME has also been discussing the issue of evaluation of team-based CPD, particularly in terms of the relationship between team-based CPD and the regulatory requirements for individual education and assessment for licensing. She said that ACCME recently brought together CPD providers and licensing bodies from the nursing, pharmacy, and medicine fields to talk about these challenges. She concluded that these organizations and fields may need to work together to develop a system that can “use a lot of these tools and resources to account for multiple [licensing] requirements.” Benton joined in, saying that there are efforts under way to make the disparate licensing requirements less onerous through the

Nurse Licensure Compact, which allows nurses to hold a multistate license and practice in any of the 25 states under the compact.

Benton summed up the conversation with a statement about the progress being made in alleviating regulatory barriers and making the system of CPD and licensure more efficient:

I think what we are seeing here is a willingness, not just within the United States, but globally, to start to sort out some of these barriers and . . . consider ideas from other disciplines and from other parts of the world. Our health systems are facing incredible pressures, and unless we start to really incentivize efficiencies, we are not going to be able to meet the needs of citizens at a national and global level.

Role of Data

Panelists discussed the use of data to guide CPD and credentialing. For example, Benton said that in Portugal the nursing board can download aggregated information about what nurses are doing day to day. This information helps to guide the requirements for continuing education and to shape the curriculum of the CE to meet the needs of the nurses. Benton also told participants about a system called Nursys, which allows people to see if and where a nurse has an active license to practice. In addition to licensure status, the system will soon include information about nurse credentials.

Regnier also commented that she sees data and health informatics as an amazing opportunity for all the health professions within credentialing, licensing, and accreditation. For example, the idea of connecting data from electronic health records with education can help promote standards and consistency of care and treatment across the education-to-practice continuum, she said. The question is how to make sure the health professions are working in sync with those in health informatics.

Workforce Well-Being

Mazmanian asked the panelists for their thoughts on how CPD could be used to promote the mental and physical well-being of health care providers themselves. Regnier said this issue is “increasingly at the forefront,” and that professional education “can be about more than the clinical care recommendations.” In addition, professionalism, communication, teamwork, and team support are all appropriate topics for education and can contribute to provider well-being. She added a comment about the medical respiratory intensive care unit (MRICU) intervention that was previously discussed at the workshop (see Chapter 4). This was a great example of how learning and working with a team can create connection and community among providers and improve well-being.

Presenters mentioned several initiatives that have been undertaken in an effort to improve well-being within the workforce. This includes the American Nurses Association’s Healthy Nurse, Healthy Nation challenge, a Scottish program called Balanced Working Lives, an international program called Positive Practice Environments, and the ANCC-credentialed program Pathway to Excellence. Both Regnier and Chappell said that initiatives to improve well-being—whether these include education specifically targeted at the workforce, or initiatives like the MRICU project that have tangential benefits for the workforce—meet the guidelines for accreditation and should count as CPD.

Harvison concluded that while accreditors certainly have a role to play by requiring content and outcomes on such issues as resilience, health, and wellness, improving the well-being of providers “involves a culture change.” He noted that providers do not work in professional silos but in complex health care delivery environments that vary widely. For example, working in a community-based practice with underserved populations “is probably a lot more stressful than in some of these other environments.” Harvison said that improving provider well-being “involves a culture change across the system as a whole,” and that a collaborative effort is needed because individual professional associations are limited in what they can do alone.

REFERENCES

ACCME (Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education). 2016. Menu of new criteria for accreditation with commendation. http://www.accme.org/sites/default/files/731_20160929_Menu_of_New_Criteria_for_Accreditation_with_Commendation_3.pdf (accessed July 7, 2017).

Francke, A. L., B. Garssen, and H. Huijer Abu-Saad. 1995. Determinants of changes in nurses’ behaviour after continuing education: A literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing 21(2):371–377.

JAICE (Joint Accreditation Interprofessional Continuing Education). 2016. By the team for the team: Evolving interprofessional continuing education for optimal patient care. http://www.jointaccreditation.org/sites/default/files/2016_Joint_Accreditation_Leadership_Summit_Report_0.pdf (accessed July 7, 2017).

McMahon, G. T. 2017. The leadership case for investing in continuing professional development. Academic Medicine 92(8):1075–1077.

Szanton, S. L., B. Leff, J. L. Wolff, L. Roberts, and L. N. Gitlin. 2016. Home-based care program reduces disability and promotes aging in place. Health Affairs 35(9):1558–1563.

This page intentionally left blank.