6

Strengthening Partnerships and International Cooperation

Session IV of the workshop, moderated by Peter Sands, senior fellow at the Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business and Government, Harvard Kennedy School, focused on strengthening partnerships and international cooperation to combat antimicrobial resistance. The session opened with a presentation about the experience in Kenya implementing the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) global action plan on antimicrobial resistance at the country level, provided by Evelyn Wesangula, national focal point on antimicrobial resistance in the Ministry of Health in Kenya. Robert Newman, vice president and global head of the tuberculosis (TB) program at Johnson & Johnson Global Public Health described experiences in developing and deploying bedaquiline, a novel anti-TB drug, to illustrate the importance of partnerships in driving global action. Angela Siemens, vice president of food safety, quality, and regulatory at Cargill Protein Group, provided a food industry perspective on improving the safety of the global food supply chain. Kathy Talkington, director of the Antibiotic Resistance Project at The Pew Charitable Trusts, described her organization’s work to convene experts across sectors to collaborate on solving specific problems related to antimicrobial resistance. John Rex, chief strategy officer at CARB-X, concluded the session with an overview of existing partnerships worldwide that are working to address various facets of the problem.

IMPLEMENTATION OF THE WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION’S GLOBAL ACTION PLAN ON ANTIMICROBIAL RESISTANCE AT THE COUNTRY LEVEL

Wesangula provided a country-level perspective on the experience of Kenya adapting the WHO’s global action plan on antimicrobial resistance into its own national action plan (WHO, 2015b). She hoped that sharing the Kenyan experience would assist other countries just beginning this process. She reported that about half of deaths among Kenya’s population of 48 million are due to infectious diseases, so the use of antimicrobials remains critical. To optimize the use of antibiotics in both human and animal health, Wesangula underscored the need to develop new antibiotics and improved rapid diagnostic techniques.

Process of Policy Formulation

In Kenya, formal policy development on antimicrobial resistance began in 2009, Wesangula said, after a growing body of evidence showed rising resistance trends caused by overuse of antimicrobial agents both in humans and animals. However, the evidence being accrued was not coupled with government action to develop and implement policy action, she said. Thus, an expert working group was convened by the Kenya Medical Research Institute with support from the Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics and Policy, which was followed by the formation of a Joint Taskforce between the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, and Fisheries in 2010. In 2011, the Situation Analysis and Recommendations on Antibiotic Use in Kenya report was released (GARP-Kenya Working Group, 2011). By the time the global resolution to combat antimicrobial resistance was endorsed by the World Health Assembly in 2014, she explained, not much progress had been made in Kenya at the national government level to implement the strategies recommended by the situation analysis because of a new constitution in 2010, which mandated a transition from a centralized system of governance to a devolved system of governance. However, momentum in addressing antimicrobial resistance began gathering within the next year, Wesangula said, in the wake of further global and national initiatives aligned with the multisectoral One Health approach. Spurred by the 2005 International Health Regulations (IHR), which includes a core capacity requirement for national progress reports about antimicrobial resistance tracking, she said, the Kenyan Infection Prevention and Control Strategic Plan (2014–2017) recommended establishing a national integrated surveillance system and advisory committee for antimicrobial resistance. In 2015, the Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA) prompted increased governmental effort toward addressing antimicrobial resistance, said Wesangula.

Developing Kenya’s National Action Plan

“The big job for us was breaking down the global action plan [to our national policy and action plan], knowing that the challenge is global, but really the solutions to antimicrobial resistance must be localized as much as possible because countries are different,” reflected Wesangula. Throughout 2016, consultative workshops engaged diverse stakeholders to build synergy toward a coherent, country-specific, country-owned national action plan. She reported that relevant constitutional and sector-specific policies were reviewed to find ways to leverage antimicrobial resistance, and Kenya’s existing commitments to international policies on resistance were also considered. She added that national and international stakeholders were involved throughout the progress (e.g., the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations [FAO], the World Organisation for Animal Health [OIE], WHO, and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]). Wesangula reported that process was completed in May 2017 with the release of the National Policy on Prevention and Containment of Antimicrobial Resistance (Government of Kenya, 2017).

Achievements, Successes, and Barriers Encountered

Wesangula surveyed the Kenyan national effort’s achievements and barriers encountered to date. An active multisectoral national advisory committee continues to lead the process in accordance with the One Health approach. A new integrated national surveillance strategy was developed concurrently with the national action plan, she said, which is being implemented in four pilot sites in the country. She added that Kenya has enrolled in WHO’s Global Antimicrobial Surveillance System (GLASS) and a national communication strategy is helping to communicate the risk of antimicrobial resistance, with support from a dedicated media network, in ways that are clear and appropriately pitched for the public.

The biggest barrier in engaging the highest level of policy making, according to Wesangula, has been lack of awareness, largely because of insufficient data on the economic cost of antimicrobial resistance. “Our policy makers want to see numbers,” she said. “What would it cost if we did not act? What can we save if we have interventions in place?” In the advisory committee, disproportional representation from the human medical sector has also been a barrier, she said. Funding has posed another big challenge, she added, and has been heavily reliant on partnerships and collaborations that require complex coordination.

Wesangula used surveillance-related challenges to illustrate some of the ways they have surmounted barriers. To build a surveillance system upon poor infrastructure and virtually no data, she said, they partnered with

and leveraged the infrastructure of established academic, private-sector, and World Bank–supported laboratories to enhance capacity to accurately detect and report antimicrobial resistance. To bolster workforce capacity, they created onsite and online mentorship programs as well as a field epidemiology training program. She added that upgrading information technology and databases has improved problems with reporting and data management. To improve quality, she said, they established a national calibration center and a system to accredit laboratories.

Wesangula concluded by reviewing lessons learned from the process of implementing the national plan in Kenya. She said that multisectoral platforms work best from inception, if possible, and that it is important to identify and clearly define the burden of antimicrobial resistance in order to engage policy makers. Government leadership and political commitment are critical for pushing the resistance agenda, she continued, and implementers should be involved throughout the process. For instance, medical students work to engage the community during Antimicrobial Resistance Awareness Week, she said. Planning needs to be realistic, she warned, because it can take years to garner meaningful stakeholder engagement. Finally, she advised that the process should be driven by persistence, patience, collaborative relationships, and trust building.

IMMEDIATE STRATEGIES TO DEVELOP OR REFINE PARTNERSHIPS

Partnerships in the Age of Bedaquiline: Successes, Challenges, and the Beginning of the End of Tuberculosis

Newman explained that the pipeline for new TB drugs has been virtually empty since 1965, despite the enormous and growing burden of multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) worldwide. According to WHO data, there are nearly 600,000 incident cases of MDR-TB per year, of which less than one-quarter are treated and only half of those treated are cured (WHO, 2016). Janssen Pharmaceuticals (the pharmaceutical company of Johnson & Johnson) developed bedaquiline with a novel mechanism of action called an adenosine triphosphate synthase inhibitor, which was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2013. Around 30 percent of adult patients with MDR-TB and extensively drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB)1

___________________

1 According to WHO, MDR-TB involves resistance to the two most effective anti-TB drugs: isoniazid and rifampicin. XDR-TB involves resistance to those two drugs, as well as to any fluoroquinolones and to at least one of the three injectable second-line drugs (amikacin, capreomycin, or kanamycin).

are eligible for bedaquiline as part of combination therapy, he said, which amounts to around 37,000 patients worldwide.

Bedaquiline at the Core of Collaboration

Newman explained that making bedaquiline available to each patient who needs it—the ultimate goal—is stymied by constrained funding, weak health care delivery systems, limited diagnostic capacity, poor prescribing and adherence practices, patient populations with limited resources, and inadequate standards of care. But at the core of the many challenges faced in the TB sphere, he argued, is complacency and lack of urgency. He suggested that by enabling an improved standard of care, bedaquiline is driving collaborative efforts around TB by galvanizing a renewed sense of optimism that addressing drug-resistant TB is not a hopeless endeavor. The many partners involved in the rollout of bedaquiline, he said, include the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), PATH, the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, the Global Drug Facility (GDF), the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the TB Alliance, Pharmstandard, and the Stop TB Partnership. On the regulatory side, he reported that as of May 2017 bedaquiline had been registered in countries that cover 70 percent of the high-burden countries for MDR-TB, and the process is ongoing in other high-burden countries. Newman observed:

It takes an enormous amount of partnership to help governments change TB programs that haven’t seen a new drug in a long time, and to actually build a system of stewardship around bedaquiline so that we’re sure it reaches the patients who need it, but we don’t foster the development of resistance for a drug that we desperately need.

Collaboration in High-Burden Countries

Newman surveyed the collaborations under way to deploy bedaquiline in three high-burden countries. He commended South Africa as a leader in engaging partners and sustaining investments. He added that the bedaquiline rollout included the introduction of routine audiometry, which revealed that ototoxicity, which refers to damage to the inner ear, is a major problem in existing regimens that had not been identified before. Most importantly, Newman emphasized, the drug is saving lives: treatment outcomes in XDR-TB patients (and pre-XDR-TB patients)2 taking bedaquiline are now over-

___________________

2 Pre-XDR TB is defined as in vitro resistance of the patient’s isolate to (1) isoniazid, (2) rifampin, and (3) either a fluoroquinolone or at least one of three injectable second-line drugs (amikacin, capreomycin, or kanamycin). See www.who.int/selection_medicines/committees/expert/20/applications/Bedaquiline_Janssen.pdf (accessed August 28, 2017).

taking outcomes for MDR-TB patients who are not taking bedaquiline. As part of its goal to eliminate TB, India is planning to scale up bedaquiline administration to 156 sites in 2017, he said; given its huge population and incredibly complex health system, this effort is dependent on an extensive network of partnerships. Bedaquiline is set to launch commercially in China in 2019, reported Newman, and the country is laying the groundwork through a controlled access program driven by national and international partners. Newman said that the 4-year bedaquiline donation program—a partnership with USAID, GDF, and other partners—has a commitment to fund up to 30,000 treatments in more than 100 low- and middle-income countries meeting Global Fund eligibility criteria who agree to appropriate use per WHO guidance.3

Innovation for Tuberculosis Therapeutics

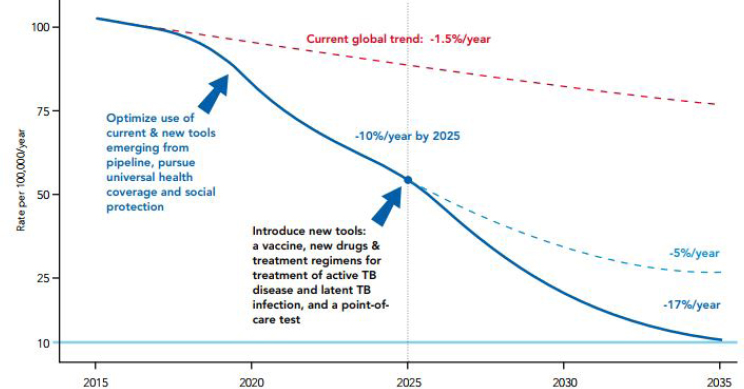

As of May 2017, Newman estimated that bedaquiline had been received by more than 19,000 patients in over 80 countries, but he warned that progress against TB needs to be accelerated by reducing the lag between innovation and uptake. The incidence of TB is currently decreasing at an unacceptably low rate of 1.5 percent per year, he reported. Eliminating the global burden of TB—a disease that has been curable since 1946—will remain aspirational without accelerated discovery, development, and deployment of new tools and technologies, said Newman (see Figure 6-1).

Newman warned that therapeutic innovations for TB are urgently needed because current treatment regimens are very long (bedaquiline is part of a 24-month course), often involve injectables, and are associated with many adverse effects. He suggested that innovation needs to be directed toward all-oral, shorter-course, fixed-dose combination regimens with low toxicity, with more far-reaching goals of a vaccine and of a pan-TB regimen for both drug-sensitive and drug-resistant TB. The broader problem of TB infection—sometimes referred to as “latent TB”—also looms large, he cautioned. An estimated 2 billion people worldwide are infected with TB, Newman said, and around 10 percent of those people will go on to develop the active disease. “Turning off the tap” by treating TB infection in people before they progress to active disease is a critical aim, he argued. Although Johnson & Johnson has new tools under development with bedaquiline as a foundation in terms of shorter regimens, new platforms, and novel targets,

___________________

3 During the discussion, Newman clarified that the name donation program is somewhat of a misnomer; the term accelerated access program is more apt, because its aim is to remove the issue of price to improve drug availability, but it also incorporates country-level policy changes, capacity building, and collecting safety data to further inform international-level policy.

SOURCES: Newman presentation, June 21, 2017; WHO, 2015a. Reprinted from The End TB Strategy, “Actions to Impact,” page 11, Copyright (2015).

Newman said, the current market for TB drugs lacks the necessary pull incentives to drive the innovation so urgently needed.

Bedaquiline as an Accelerator for Innovation

Incentivizing further innovation will require demonstrating the readiness to capitalize on emerging innovations, Newman said, and to deploy them to affected people as quickly as possible. Expanding the impact of new technology, however, he added, requires having the appropriate infrastructure in place for stewardship, controlled distribution, and surveillance. Health system capacity is a huge barrier in rolling out new interventions, he said. Newman predicted that progress toward strengthening infrastructure and capacity during the bedaquiline rollout may ultimately help to unlock the broader transformational potential that addressing drug-resistant TB could have on the global impact of antimicrobial resistance. For example, he suggested that it could aid in creating a blueprint for addressing antimicrobial resistance in developing countries. See Box 6-1 for other ways that Newman suggested the bedaquiline experience might inform the development of new tools and improve the ecosystem of antimicrobial resistance.

Integrating Food Safety, Animal Health, and Plant Health to Improve the Integrity of the Food Supply Chain

Siemens provided a perspective from Cargill on the value of partnerships and international cooperation in the food industry. Cargill is among the largest private companies in the world, operating in 70 countries across multiple sectors in the global food supply chain. Cargill has been working for many years on ensuring food safety and applying safety standards globally. She noted that many of the issues regarding systems, partnerships, and knowledge sharing being discussed in the workshop are also pursuant to food safety. Siemens provided an overview of several organizations that are working to disseminate best practices in food safety across the world in a competitive, market-driven industry.

The Global Food Safety Initiative and SSAFE

The Global Food Safety Initiative (GFSI) is a voluntary initiative of the global food industry to enhance food safety practices and consumer confidence, explained Siemens. Established in 2000, GFSI addresses critical issues affecting supply chains and enhances food safety by facilitating the sharing of expertise and best practices among food professionals, she said. It also benchmarks food safety management schemes to increase consumer confidence and reduce costs for both producers and consumers, she added. Through GFSI, she explained, major retailers agree to require manufacturers entering their food supply chains to meet established minimum verified standards for food safety. Ten food safety verification schemes are currently recognized, with more than 85,000 certificates issued to suppliers worldwide, she reported, with suppliers benefiting from streamlining their processes and gaining new business. She suggested that the voluntary verification piece through third-party audit in the private sector may be applicable to antimicrobial stewardship programs outside the auspices of the regulatory realm. Through an annual global summit, she continued, GFSI facilitates dialogue about food safety regulations between private sector and the government—especially in countries that have not yet focused on food safety—about whether these global standards may be appropriate for regulatory environments. Facilitation between governments has made strides against the problem of nonharmonized regulations in the food security space, she said. To avoid excluding resource-constrained smaller food and animal suppliers from the market, Siemens explained, GFSI has adopted a “go-to-market” system. Suppliers can continue to sell into the marketplace while they are supported in working toward their full certification. Suppliers typically enjoy the correlate benefits of improvements in the production management process that a food safety management system generally entails, she added.

In the context of setting up such a global private-sector organization, Siemens recommended setting a specific and focused vision. For GFSI, for example, it is only about standard setting. Specifically, she said that the objective is to improve food safety by delivering equivalence and convergence between effective food safety management systems:

When I talk to someone in China and they receive a certificate, I know what the standard is by which they received that certificate and I can have confidence in the product they are sending me.

She emphasized that GFSI does not set policy for retailers or manufacturers, undertake training, or accredit or certify suppliers directly. Siemens explained that other organizations, such as SSAFE (Safe Supply of Affordable Food Everywhere), carry out training that GFSI does not undertake.

Initially, SSAFE was established to support training through public–private partnerships to contain the spread of high-path avian influenza, she said. It is now working on facilitating food safety education and training in developing countries. SSAFE is currently rolling out a global food safety training framework for dairy farming that can be used in cooperation with GFSI, Siemens reported.

Competition and Precompetition in Animal Agriculture

In the context of animal agriculture relative to antibiotics, Siemens said, it is important to consider the competitive versus precompetitive aspect. She expressed concern about how to ensure that there are precompetitive discussions to collaborate and innovate when antibiotics represent a competitive advantage, particularly in the United States. Recent research demonstrates that consumer interest in reduced use of antibiotics is increasing, she reported, and some companies are indicating that they are willing to meet this market demand. However, she said that there is still a gap between consumers who profess that antibiotic-free meat is important to them and those who actually purchase antibiotic-free meat. She suggested that attracting those consumers to purchase antibiotic-free meat, and bringing more of that product to market, is a market opportunity. She observed, “a company, especially in the U.S. in the competitive set, is going to look for that differentiated competitive position; they’re going to have improved performance and long-term growth.” However, Siemens noted that this is challenging the industry because food safety was declared a noncompetitive item in 2001 by the meat industry. But to solve this overall problem, she said, there needs to be precompetitive discussions—despite marketplace competition—about stewardship, best practice sharing, and aligning metrics in the animal agriculture sector.

The Pew Charitable Trusts’ Role in Strengthening Partnerships in the Fight Against Antibiotic Resistance

The Pew Charitable Trusts is engaged in the issue of antibiotic resistance, said Talkington, in the areas of stewardship, animal agriculture, and drug innovation. One of Pew’s primary strategies, she said, is to serve as a convener by bringing the right people to the table from multiple sectors to collaborate by aligning interests to affect change against the unique challenge of antibiotic resistance. She emphasized the value of partnerships in addressing this complex problem of antimicrobial resistance, and in her opinion, partnerships are particularly important given the urgency of the situation. She cautioned that the window of the opportunity in terms of interest in antibiotic resistance will not necessarily last, so harnessing the

current enthusiasm is critical to moving the issue forward. Partnerships also help to avoid the duplication of efforts, Talkington said, and to ensure the optimal use of partners’ respective skills and expertise. She presented some of Pew’s work in the antimicrobial resistance sphere.

Preserving Antibiotics for Patients Who Need Them

Talkington described Pew’s work on the issue of preserving antibiotics for those patients who really need them, part of which translates into reducing the inappropriate use of antibiotics. The U.S. action plan sets forth the target of reducing antibiotic use in the outpatient setting by 50 percent by 2020 (PACCARB, 2016), and Pew has worked to make that goal actionable in partnership with CDC, she said, by convening a group of frontline implementers—including primary care physicians, emergency care doctors, and other participants in the outpatient arena—to explore methodologies for applying existing information.

Reducing the Need for Antibiotics in Animal Stewardship

The issue of antibiotics in animal agriculture is complicated, Talkington said, with a wide variety of players coming to the table with different challenges and goals in mind. Government, international organizations, the private sector, and pharmaceutical companies are all involved, she said. To find common ground between such a diverse set of partners, a meeting was convened in 2016 by OIE and the U.S. Department of Agriculture to examine alternatives and potential research priorities for reducing the need for antibiotics in animal agriculture; she reported that the area seems very promising. An additional benefit of channeling such diverse voices in a uniform way, she said, is the opportunity to use that common voice to advocate for additional resources in order to fund the research needed to study potential alternatives.

Spurring Innovation Through Data

Data are also a powerful tool for spurring development and innovation, Talkington said. Given that no registered classes of antibiotics have been discovered since 1984, she said, the antibiotics being used today are based on 30-year-old research. This is a problem and a failing of the current system, she said, but the solutions are complex. Pew initially focused on the scientific challenges for discovery of antibiotics, convening a diverse group of experts to identify next steps, and that chief among them is the need to share data and information, she said. She reported that currently, there is no available mechanism for facilitating the large amount of pub-

licly available data in research (e.g., from failed studies or former manufacturers). She said they are preparing to launch a new program called the Shared Platform for Antibiotic Research and Knowledge. As a first step, it will collect publicly available data targeted toward gram-negative bacteria issues, Talkington said, which will be curated by experts seeking to identify specific questions or patterns so that data can be made readily available to the research community.

THE ROLE OF PARTNERSHIPS IN ADDRESSING ANTIMICROBIAL RESISTANCE

Rex spoke from the perspective of an infectious disease doctor with extensive academic and industrial experience in developing new drugs and diagnostics. He began by reflecting on the term antimicrobial resistance, suggesting that it confuses the layperson because it suggests that somehow the person becomes resistant to an antibiotic, so if a person does not take that specific antibiotic, then they cannot be resistant. The term drug-resistant infection (DRI) more often conveys the right message, he said (Mendelson et al., 2017).

Rex identified three informal levels of increasing complexity in partnership. The simplest level is sharing information and methods. The next level involves adding on the joint setting of priorities and scale, he said, which can enable partnerships to become competitive at the international level. The most complex level, he continued, involves adding on the component of risk sharing and intent to create public goods with market potential or knowledge. Rex aligned his informal model to WHO’s global action plan to survey the current partnership landscape.

Sharing Information and Methods

Relative to WHO’s global action plan, Rex explained, the first level of partnership—sharing information and methods—involves awareness and understanding of DRI. This includes improving awareness of DRI, reducing the incidence of infection, developing an economic case, and optimizing use of antibiotics, he said. Partnerships focusing on awareness at this level tend to be easily replicated, he added, and include the Euro AMR Barometer,4 along with CDC’s Get Smart About Antibiotics.5 In partnerships focusing on reducing the incidence of both susceptible and resistant infections, he noted that action is local (“one hospital at a time”) but experience can

___________________

4 For more information, see ec.europa.eu/health/amr/antimicrobial-resistance_en (accessed July 31, 2017).

5 For more information, see www.cdc.gov/getsmart/index.html (accessed July 31, 2017).

be shared and transferred. Sharing information about optimizing the use of antibiotics is straightforward, he said, through national and regional guidelines for human use of antibiotics, for example, and through sharing methods to reduce and eliminate animal use. Partnerships in the realm of sharing scientific knowledge are CARB-X, a public–private partnership that funds preclinical research, and the Global Antibiotic Research and Development Partnership (GARDP), a program that seeks to deliver data and products addressing specific gaps.

It is exceedingly difficult, Rex warned, to make an economic case for sustainable investment in new medicines, diagnostics, and vaccines:

Anyone who sets out today to develop a new antibiotic is engaging in a 30-year exercise that is almost guaranteed to destroy $50 million in terms of net present value.

An economic tension arises because the greatest value of antibiotics is their nonuse, he said, likening them to the fire extinguishers of medicine: “If you don’t have a fire extinguisher on hand, the building goes down; there is no opportunity to build a fire station at the time that you observe the fire.” However, he noted some ongoing global conversations about innovative approaches. DRIVE-AB, an Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI) project in the European Union, is a 3-year, multistakeholder effort to create novel business models, he said. The Duke-Margolis antimicrobial payment reform project, which Gregory Daniel, deputy director and clinical professor at the Duke-Margolis Center for Health Policy, discussed earlier in the day (see Chapter 5), is an FDA-funded project on delinking use from profit, Rex noted, and the United Kingdom’s Review on Antimicrobial Resistance produces reports and convenes workshops in the area.

Joint Priorities and Scale

At the level of partnership with joint priorities, Rex continued, optimizing the use of antibiotics involves strengthening knowledge through surveillance. He provided several examples of those types of research and development networks. GARDP is analyzing the use of antibiotics in neonatal sepsis and sexually transmitted infections in several networks. The European Union’s Joint Programming Initiative on Antimicrobial Resistance is obtaining national-level money to fund projects across Europe, he said. The Wellcome Trust is developing a collaborative clinical trials network to help deliver the registration data required to get new drugs approved (McDonnell et al., 2016). Rex also provided examples of partnerships with joint priorities at a global scale that are strengthening knowledge through surveillance: the UK Fleming Fund, a £256 million government investment

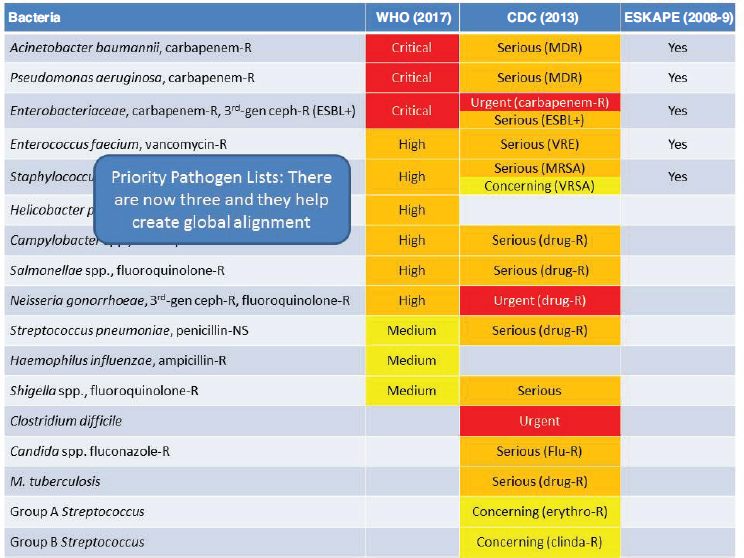

NOTE: -R = -resistant; CDC = U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; ESBL = extended-spectrum beta-lactamases; ESKAPE = Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter pathogens; MDR = multidrug resistant; MRSA = methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; VRE = vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus; VRSA = vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; WHO = World Health Organization.

SOURCES: Rex presentation, June 21, 2017; from CDC, 2013b; WHO, 2017b.

in improving laboratory capacity for diagnosis and surveillance of antimicrobial resistance; and WHO’s GLASS. CDC’s National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS) (see Chapter 2) is doing the same thing at very large national scale, he noted. Rex said that the three priority pathogen lists are in good alignment (ESKAPE6 as well as lists from both WHO and CDC), which is in effect setting joint global priorities about the drugs that are most needed (see Figure 6-2).

___________________

6 ESKAPE pathogens include Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter.

Risk, Knowledge, and Market Goods

Partnerships at the highest level of complexity create knowledge and goods, both public and private, Rex explained. Because of the scale, the synergies that flow from any such partnership can have extraordinary impact, he added. He cited three examples of such partnerships. Rex explained that the IMI is a €2 billion program that is a collaboration funded by the European Commission with in-kind funding from the pharmaceutical industry in Europe to create multicompany, multiacademic group projects (designed to be precompetitive). One such program is the New Drugs for Bad Bugs program, which is the biggest part of IMI and has spawned seven projects on collaborative drug discovery, drug development, and economics and stewardship, according to Rex.

Rex’s organization, CARB-X, is a pooled funding mechanism with $455.5 million committed by the U.S. government and the Wellcome Trust so far. Its goal is to accelerate preclinical research and development on antimicrobial therapeutics, diagnostics, and preventatives through phase I, he explained, with plans to fund 50 preclinical projects over the next 5 years. It is a public–private partnership that also leverages capital from private partners, he said. Rex explained that CARB-X was designed with a set of portfolio priorities. He said that new direct-acting therapies for gram-negative bacterial infections are the highest priority, followed by rapid diagnostics and diagnostics that predict susceptibility. He predicted that at least one novel mechanism agent supported by CARB-X will be registered in the next 10 years.7

The way that antibiotics are purchased must change, argued Rex, because in economic terms, antibiotics are a positive externality. He explained: “You benefit from it even if you don’t personally use it, but I can’t charge you for the fact that you benefit from it.” Positive externalities are classically dealt with in economics by government-level subsidies such as market entry awards, he added. Such incentives have not yet been implemented, he continued, and will require global coordination through shared target product profiles to assist drug developers, as well as some global allocation of financial obligation.

DISCUSSION

Suerie Moon, director of research at the Global Health Centre, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva, noted that in aspects of the global politics of antimicrobial resistance, there are ten-

___________________

7 Rex reported that the first 11 awardees cover three novel class candidate small molecules, four nontraditional products, seven new antibacterial targets, and one point-of-care diagnostic for nosocomial pneumonia.

sions at play between the need to reduce antibiotic use in animal agriculture and the commercial or economic interests in developing those industries. She asked Wesangula whether such tensions arose in Kenya during the development of the national strategy. Wesangula replied that such tensions have not yet arisen because they consulted with the agriculture and livestock industry throughout the process, building trust and explaining the importance of appropriate antibiotic use. However, she noted that the real test will come when the required standards for antibiotic use are implemented. Dennis Carroll, director of Global Health Security and Development Unit, USAID, asked Wesangula about potential increases in antibiotic misuse across sub-Saharan Africa, given the data predicting that economic and demographic changes occurring within the region will dramatically increase livestock production. He asked about any policies and regulations to deal with food security and antibiotic stewardship in animal agriculture. Wesangula noted that Kenya’s current health reforms are creating new institutions within the government—such as the independent Kenya Food and Drugs Authority—that may help to navigate these complicated issues, as well as addressing problems with enforcing compliance to regulations governing human and animal health, including antibiotic use.

Kumanan Rasanathan, chief of the Implementation Research and Delivery Science Unit at the United Nations Children’s Fund, asked about the extent of political buy-in in Kenya across sectors at the ministerial level and, given the government’s recent decentralization, the county level. Wesangula replied that after year-long engagement efforts, the Minister for Health and the Minister for Agriculture, Livestock, and Fisheries clearly understand the issues and are committed to pushing the antimicrobial resistance agenda at the country level. In terms of decentralization, she noted that the county level governs the actual implementation of the standards set at the national level. To facilitate relationships between the national and county levels, she said, they have developed intergovernmental mechanisms and engaged hundreds of representatives across sectors at the grassroots county level. She was optimistic that this engagement will ease the implementation process. Marcos Espinal, director of communicable diseases and health analysis at the Pan American Health Organization, remarked that he considers the GHSA—a nonbinding multicountry initiative—to be a catalytic initiative to help the IHR, which is a binding legal treaty. Wesangula noted that in Kenya, the GHSA was a strong catalyst for the government’s response to antimicrobial resistance, even though it is nonbinding.

Espinal asked Newman if the pharmaceutical industry is working to develop new tools for addressing the problem of latent TB, which he considers to be a critical public health issue. Newman agreed that stemming the tide of the TB epidemic will not be possible without addressing latent TB infection; he noted that there are different possible approaches. One

strategy is to develop ways to predict which people are likely to progress to active TB and treat those people, he said. Another strategy is to develop a simple diagnostic test to detect TB infection and then to treat all infected people with a new safe, well-tolerated, and simple regimen, said Newman, such as a super long-acting injectable. He said that long-acting delivery systems are under development for other diseases, and they may be applicable to TB. Moon asked Newman to elaborate on any lessons about stewardship gleaned from the bedaquiline experience that might be broadly applicable to antimicrobial resistance. Newman commented on the need to strike a “balance between trying to make sure that you’re being good stewards of a new molecule but, also not doing that to the point of impeding access to the people who need it.” Capitalizing on new molecules is important, he said, but shorter-term efforts should focus on building capacity in national TB programs to responsibly deliver imminent new regimens with existing drugs, such as bedaquiline, delaminid, or pretomanid. He said that new diagnostic and drug sensitivity tests for TB would be transformative against the epidemic.

In the context of CARB-X’s strategy of early investment in preclinical research and development and interest in market entry rewards, Moon asked Rex about the possibility of putting provisions into those early-stage grants to ensure that any of those future drugs adhere to certain public health principles, such as sustainable use and equitable access. Rex replied this will be fundamental in affecting the needed change in the antibiotic development process, and CARB-X is building such provisions into its contracts, starting with principles and a subsequent road map espoused by the Davos Declaration, which is a collective action agreement among more than 100 entities in the pharmaceutical, biotechnology, and diagnostics industries to guide the development and stewardship of new antimicrobial products (see Chapter 3). An important component of the Davos Declaration, said Rex, is that it requires country engagement after the industry develops the new drugs. He warned:

We have, for too long, used antibiotics as a cheap band aid for bad infrastructure. It has been cheaper to treat the diarrhea than to provide the adequate infrastructure to provide clean food, clean water, and appropriate sewage, than to provide the vaccines. Antibiotics have been too easy in that (a) it’s a pill that you put in somebody’s mouth and, (b) it has been cheap. And it has been viewed as a cheap substitute for doing the hard stuff.

Lonnie King, professor and dean emeritus at The Ohio State University College of Veterinary Medicine, asked Rex about the potential for transferring knowledge related to antibiotics that were developed, but ultimately not approved, to animal health and to vaccine development. Rex replied that the notion of a “graveyard” of pharmaceutical failures is largely

mythical; therapeutics are discarded because they did not work then and will not work now. In terms of animal antimicrobials, he said that efforts are better spent keeping the pressure on new development. As for vaccines, Rex explained that the animal immune system is quite different from the human immune system and translational failures between the two have been more the rule than the exception. He did note that GARDP has an ongoing project, the Antibiotic Memory Recovery Initiative, which tries to gather knowledge from the older generation of antibiotic researchers that might be relevant for the new generation of researchers.

King asked Siemens about the incentives that were used to create great interest in certification and about any suggestions applicable to a similar certification program for an animal health stewardship program. Siemens responded that in the food safety space, interest in certification was driven by competition and market access; a milestone occurred when seven major retailers signed on to require certification (a process that took place over several years). In the last 10 years, she said, interest has been further accelerated by issues with global food safety and consumer confidence about the integrity of the supply. The go-to-market program is also crucial, she said, in enabling food supply security in resource-constrained settings. She advised implementing some form of verified stewardship program to ensure judicious use but also to integrate animal welfare and some appropriate use of antibiotics. In Cargill’s animal nutrition business, she said, they are seeking alternatives to broad-spectrum antibiotics, but they are not as consistently effective. Reducing use in animal populations can have unintended consequences, she warned. Siemens referred to emerging evidence that withdrawing antibiotics changes the microbial profile of the animals, for example, causing elevated rates of subclinical Salmonella among chicken flocks. She emphasized the need to leverage the precompetitive space in animal agriculture to address these types of dynamics.