9

Timely Access to Mental Health Care

Timely access to care is an essential aspect of health care quality. The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is working to overcome the significant and well-documented challenges it has faced in providing veterans with timely access. This chapter examines multiple dimensions of timely access to mental health care. It summarizes the published research regarding wait times, wait-time data collected within the VA, the qualitative site interview data obtained as part of this study, appointment scheduling practices, cancellation and missed appointment practices and policies, the VA’s efforts to improve timely access, and suggestions for improvement from site visit interviews. The survey results from this study regarding timely access are noted in this chapter but reported in detail in Chapter 6 under the heading Barriers and Facilitators to Service Use.

There is no national consensus on what an acceptable length of time to wait for a medical appointment is, be it for a primary care, specialty care, or mental health care appointment (IOM, 2015). Nevertheless, many health networks have set their own standards for appointment wait times—which may be different for different appointment types—that their participating providers are required to follow (Medica, 2016; Partnership Health Plan of California, 2016; Peach State Health Plan, 2016; Superior Health Plan, 2016). At the VA, the need to improve wait times and scheduling has been an ongoing issue and has been the source of much controversy and critique. Technological improvements have been introduced to help solve problems related to timely access, but various implementation challenges have hampered success. In multiple reports since 2005 the VA Office of Inspector General and the Government Accountability Office (GAO) have both called for improved scheduling practices, decreased wait times, and improved wait-time data collection at the VA (GAO, 2012, 2015, 2016a; VA Office of Inspector General, 2005, 2007, 2012, 2016, 2017b).

The Institute of Medicine found that veterans face a variety of timely access to care issues when seeking mental health care for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (IOM, 2014). Problems related to access to care were found at many facilities, including wait times of weeks or months when seeking PTSD care, long wait times for evidence-based treatments for PTSD, evidence-based PTSD treatment not being offered at the required frequency, inadequate after hours and weekend appointments for PTSD treatment, and gaps

in tele-mental health capacity (mostly due to staff shortages) (IOM, 2014). Other studies have found that wait times can vary greatly across facilities (RAND, 2015a). Building on those findings, this section will highlight some of the ongoing issues with wait times and scheduling at the VA as reported in the literature. It will also summarize the findings from the committee’s site visits that are related to wait times.

Although the research was not specific to veterans of Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF), Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF), and Operation New Dawn, studies of wait times for veterans have found that long wait times can compromise health because of delayed use and can lead to poorer health outcomes and decreased user satisfaction (Pizer and Prentice, 2011; Prentice and Pizer, 2007). The poorer health outcomes, which were most evident among older veterans, included increased mortality. These studies did not, however, look at wait times and the use of mental health services specifically.

WAIT TIMES AND SCHEDULING CARE

The VA’s mental health wait-time policy, outlined in Uniform Mental Health Services in VA Medical Centers and Clinics (VA, 2015b), requires that first-time patients requesting mental health care be seen for an initial evaluation within 24 hours, followed by a comprehensive diagnostic and treatment evaluation to be completed within 30 days. This policy reflects a revision made in November 2015, before which the comprehensive exam was required to be completed in 14 days instead of 30. The policy requires that ongoing appointments be scheduled within 30 days of the veteran’s preferred date (this was unchanged by the November 2015 revision) (VA, 2015b).

Before the revision was made to the Uniform Mental Health Services in VA Medical Centers and Clinics, there was conflicting information regarding the time allowed to complete the comprehensive mental health exam. In 2014, in a response to the Choice Act, the VA stated that the policy required that comprehensive exams be completed within 30 days of the initial request (GAO, 2015; VA, 2014a), which contradicted the Uniform Mental Health Services in VA Medical Centers and Clinics at the time and up until it was updated in late 2015 (VA, 2015b). The GAO reported in 2015 that a number of VA officials, including leaders of VA medical centers (VAMCs) and veterans integrated service networks, did not know if they were supposed to meet the 14-day requirement as stipulated in the Uniform Mental Health Services in VA Medical Centers and Clinics or the 30-day policy for new patients requesting mental health care (GAO, 2015).

The VA publishes monthly wait-time data showing the average wait time from the veteran’s preferred date for new mental health appointments for every facility across the system (VA, 2016a). Separately, it publishes data showing the percentage of new mental health appointments completed within 30 days of the patients’ preferred date (VA, 2016a). However, using the veterans’ preferred date as the benchmark, rather than the date of the initial request, does not align with the VA’s own policy stipulated in Uniform Mental Health Services in VA Medical Centers and Clinics, which requires appointments for new patients to be completed within 30 days of the initial request for services. In multiple reports, the GAO has made it clear that using the preferred date rather than the date of the initial request does not fully capture the actual wait time for an appointment (GAO, 2012, 2015, 2016a).

In an attempt to improve transparency about wait times and the quality of care, in 2017 the VA launched www.accesstocare.va.gov. On that site users can search for facilities by location and see the average wait times for different types of clinical appointments (e.g., mental health, women’s health) and visit type (e.g., returning appointment, new appointment). Satisfaction data by facility and appointment type are also available. The site’s quality-of-care data are limited to comparing hospital-acquired infection rates among select VA medical centers and nearby private hospitals.

In an analysis of 2015 data, RAND (2015a) assessed wait times across VA facilities. For the analysis, benchmark wait times were defined as the average wait times among the top 10 percent of facilities for each appointment type. Facility-level wait times by appointment type were compared to this benchmark.

For mental health appointments the analysis found that more than half of VA facilities (77 of 141) were below (>0.5 to 2.0 standard deviations) or far below (>2.0 standard deviations) the benchmark. The remaining facilities (64 of 141) were near (within 0.5 standard deviations) benchmark wait times for mental health. As noted later in this chapter, and in the RAND analysis of these data, the GAO and the VA Office of Inspector General have questioned the reliability and accuracy of VA wait-time data (GAO, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016a, 2017a; VA Office of Inspector General, 2005, 2007, 2017b), so it is possible that RAND’s analysis used data that under-reported actual wait times (RAND, 2015a).

Same-Day Appointments

As part of the MyVA Mental Health Access Initiative, the VA has begun efforts to ensure that same-day mental health appointments are available throughout the system. From the start of fiscal year (FY) 2016 through June 2017, the VA completed over 1 million same-day appointments to over 500,000 unique veterans through primary care–mental health integration (PC-MHI) or regular mental health clinics. Currently, approximately 30 percent of the PC-MHI workload is devoted to same-day appointments: since the first quarter of FY 2016, PC-MHI has seen a 13 percent increase in the same-day workload, while general mental health clinics have seen a 20 percent increase. The ultimate goal of the MyVA Mental Health Access Initiative is to ensure that all facilities provide access to same-day services for urgent mental health appointments. Medical center directors have committed to making them available in all medical centers by the end of FY 2016 (VA, 2017b).

The VA has said that the greatest challenges associated with providing same-day access to mental health care appointments is balancing the supply of providers with the demand for same-day service. First, the VA must ensure there is sufficient staff to allot some providers to same-day appointments. However, assigning more staff than the demand requires means that staff time is wasted. Minimizing that waste and matching the supply of same-day service with the demand is a challenge that the VA has identified as one it faces (VA, 2017b).

Providers’ Perspectives

The 21 sites visited as part of this study represented VA health care systems from across the country and from both urban and rural settings.1 In most locations VA staff reported being able to get veterans into mental health appointments well within the required 30-day time frame. Several of their comments follow.

We have same-day access available across all sites of care. . . . To the time that they’re sitting across from a physician or other medical provider to meet with them has been within 15 minutes. . . . Most of the time, it’s within 5 minutes. [Seattle, Washington]

I think we’re about 3 weeks to start individual therapy. We’ve been fortunate to keep it pretty close. That’s something we’re always watching and balancing, access to intakes and access to treatment. [San Diego, California]

The site visit teams also heard frustration from some providers about the inability to meet patient demand. As one VA clinician noted,

At the end of the day, there’s never going to be enough of us. Then we have to start thinking about how we go on our own resources to spread ourselves as thick/thin as we can in order to do a credible job with the people who are in front of us. [Hampton, Virginia]

___________________

1 Due to the time constraints of these visits, no “highly rural” or “frontier” sites were selected as part of the study.

Veterans’ Perspectives

In a study that looked at wait times and the perceived timeliness of care among VA users (of all eras) with mental health diagnoses (N = 5,185), Hepner et al. (2014) found that among patients who make routine appointments, nearly half reported being able to get appointments as soon as they wanted. Among patients who reported making urgent appointments, 42.8 percent reported getting them as soon as they wanted. The patient’s specific mental health diagnosis did not significantly affect the perception of timeliness. These perceptions of timeliness estimates are slightly better than those reported by patients receiving mental health care with public or private insurance plans (Hepner et al., 2014), but still leave significant room for improvement.

On the committee’s site visits, veterans often reported significant challenges with getting appointments in mental health care services:

After I got my service connection, it took me a year and 4 days to see my primary doctor, who was a nurse, so then they can refer you to mental health, unless it’s an emergency. [Biloxi, Mississippi]

There was a 3-month wait to get my primary consultation. Again, it was, “This is the day and time that it’s going to be. If you can’t make, too bad.” After that, I had to do another 3-month wait for my secondary consultation. After that, I got fed up with it. . . . It was absurd, so I’d stop using it. [Battle Creek, Michigan]

Veterans did not universally describe negative experiences. In each site, the committee members heard veterans describe quite disparate experiences getting into care, sometimes even when discussing the same facility in the health care network. The following two quotes, for example, are from Charleston, South Carolina:

I don’t think my case was highly unique in that there was a seemingly strong emphasis on making sure I was put into the mental health services I needed right away.

I just for the first time went to the Charleston VA . . . which I had to wait 2 months for. . . . It’s like a 3-hour drive from here, and I get there a half hour early to not be seen for my appointment, which was scheduled at 2 o’clock, until 4 o’clock. They said that it was because they were so busy.

Efforts to Improve Timely Access

The committee’s findings also suggest that some of the access successes cited by the VA staff reflect some of the strategies intended to meet the 30-day benchmark for getting the veterans connected with the system, but not necessarily connected with care. For example, the site visitors were told by VA staff interviewees that in 2014 the VA nationwide implemented “orientation groups” for veterans who were newly coming in for mental health services. One clinical benefit of these groups is that veterans learn about the types of mental health services available at the VA so that they can make informed choices about their care when a clinical slot opens:

We really work to identify what they’re ready for, so they’re not waiting on a list . . . and say, “Oh, I can’t do that. I’m not going to talk about . . . my trauma over and over and over again.” . . . As soon as they pick what they want, then we send a confidential email out to those providers who provide that specific treatment. [Topeka, Kansas]

The systemic motivation for holding orientation groups is to reduce the wait times for veterans seeking VA care, and it appears to have worked. As a clinician at a community-based outpatient center (CBOC) in Tampa said, “We’ve cut down on our wait list tremendously. We’re able to get

patients in within those 2 weeks, sometimes in the same week, sometimes even the same day, which is amazing.” A final reported goal of the policy is to “weed out” those veterans who are not yet ready to commit to treatment, as it is less disruptive to the system if a veteran drops out of an orientation group after 3 weeks than if he drops out after three meetings with a clinician whose appointments are at a premium.

While some veterans may have found this immediate connection useful, interviewees also expressed their discontent. A CBOC clinician conveyed what she had heard from her patients:

I’ve had guys say, “Are you billing my insurance company for that? Because I don’t want to pay for some group where I’m sitting in a meeting that I don’t need.” I’ve also had guys say, “I’m not taking a day off work to sit there and have somebody tell me about something. I said I want to see you. I don’t need all that stuff.” [Altoona, Pennsylvania]

The committee’s survey results (reported in detail in Chapter 6) support veterans’ perception of problems with timely access to care (see Table 6-17). Among VA users, fewer than half (40 percent) reported that obtaining mental health care through the VA was not very or not at all burdensome to obtain. About half (49 percent) of those who tried to get an appointment reported it was always or usually easy to get one. Only 17 percent indicated that they could always or usually get an appointment during evenings, weekends, or holidays. Sixty-five percent were very or somewhat satisfied with the time between requesting and receiving an appointment. However, the vast majority of veterans (80 percent) indicated that an easier appointment process was an important change the VA could make (see Chapter 6, Table 6-33). However, as discussed above, the committee did hear from veterans and providers who thought mental health services were reasonably available for veterans in their locations.

Scheduling Practices

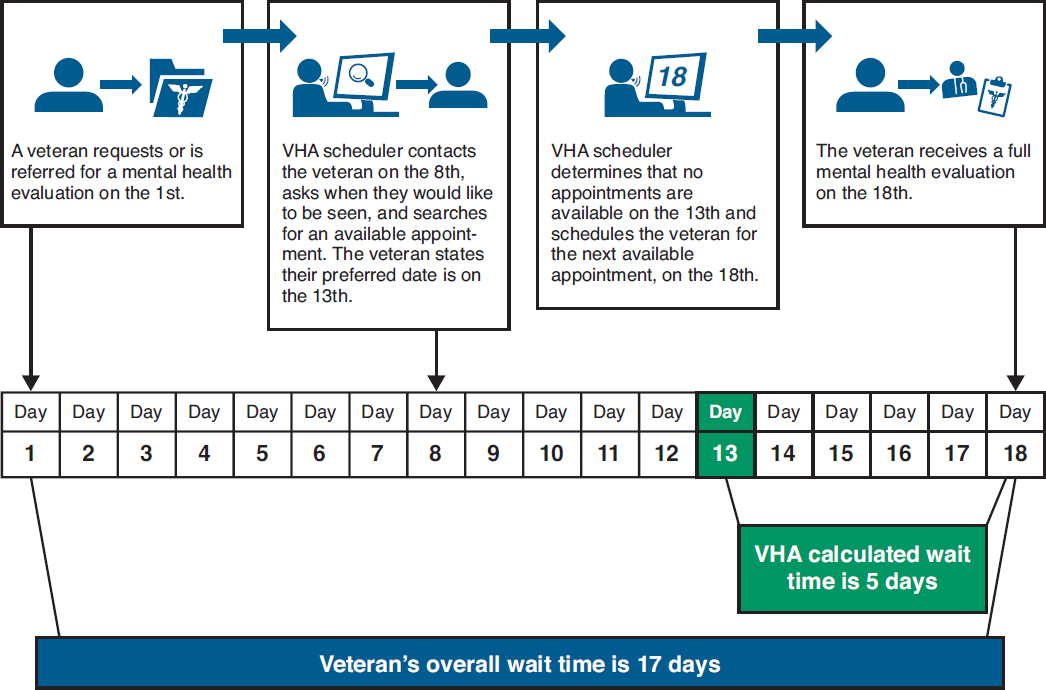

Two recent GAO reports (GAO, 2015, 2016a) discussed the issue of scheduling practices in detail. Because the VA uses the veterans’ preferred appointment date—not the date of the initial request for services or referral to services—actual wait times are in most cases several days longer than what is reported. For example, when a veteran requests mental health services, the VA scheduler may take several days to contact the veteran to schedule the appointment. The time between the request and when the VA contacts the veteran to make an appointment is not captured in the wait-time data. Furthermore, when the veteran is contacted, his or her preferred date may have already passed, which would also not be captured in the data. See Figure 9-1 below for an example that illustrates the discrepancy between actual wait times and the VA’s calculated wait time. GAO has included VA in its “High Risk List” in part because of these ambiguous scheduling policies (GAO, 2017a). GAO has assessed that the lack of clarity in the policy contributes to inconsistent and unreliable wait time data (GAO, 2017a). It calls for VA to issue guidance about the definitions used to calculate veterans’ appointment wait times and to communicate this within and outside the VA.

In 2013, the GAO reviewed VA primary care scheduling and wait times and found problems with the reliability of the recorded desired date (GAO, 2013). In 2014, the GAO reported that the VA was working to improve the scheduling systems but that continued work was necessary to ensure that scheduling problems were fully addressed in a timely fashion (GAO, 2014). However, similar wait-time and scheduling problems have been reported in GAO reports in 2015 and 2016 (GAO, 2015, 2016a) and in VA Office of Inspector General (OIG) reports from 2017, 2007, and 2005 (VA Office of Inspector General, 2005, 2007, 2017b). The VA OIG report from 2017 noted that the wait-time data the VA collects are often unreliable and found that wait times are often reported by the VA to be shorter than they

SOURCE: GAO, 2015.

actually are because schedulers often do not consistently enter correct preferred appointment dates when scheduling new patient appointments. For example, VA OIG found that schedulers entered preferred appointment dates that resulted in inaccurate wait times for an estimated 59 percent of mental health appointments (VA Office of Inspector General, 2017b).

A major inefficiency in the scheduling system is that schedulers are unable to look for available openings before the veteran’s preferred date (GAO, 2015) even though there may be openings that would be satisfactory to the veteran. Furthermore, VistA inadequately tracks provider supply and demand and is not able to schedule resources beyond the local level. It also does not adequately integrate mobile, Web, and telehealth scheduling (MITRE Corporation, 2015).

The GAO has found other frequent administrative problems with the scheduling process for newly enrolled veterans (GAO, 2016a). For example, it found that newly enrolled veterans commonly did not appear on the new enrollee appointment request list, which schedulers use to contact veterans to schedule first appointments. If veterans do not appear on the list, they will not be contacted to make their first appointment. The GAO reported that the leadership in the VAMC where this was occurring was not aware of the problem and did not know why it was happening. The report also found that schedulers frequently did not contact veterans at all to schedule appointments. In some cases they did contact them but not at the frequency required by VA policy. The GAO concluded that these administrative scheduling weaknesses may have led to unnecessary delays in care for veterans (GAO, 2016a).

In a series of reports the VA OIG concluded that improper scheduling practices in many cases may be due to inadequate training or a lack of knowledge of the required policies (VA Office of Inspector General, 2016). One practice that the VA OIG found, for example, was that some schedulers would “negotiate” a veteran’s preferred appointment date by suggesting a date on which a provider was available rather than wait for the veteran to state his or her desired date. VA OIG reports have also found some instances of intentional manipulation of wait-time data to falsely demonstrate that wait-time benchmarks are being met (VA Office of Inspector General, 2016).

The committee’s survey revealed that a large proportion of veterans are not satisfied with the mental health appointment-making process at the VA. Among veterans who screen positive for a mental health need, 54 percent of veterans who responded to the question indicated that the process of getting mental health care at the VA was very or somewhat burdensome. Among the same population of veterans, 43 percent indicated it was never or sometimes easy to get an appointment. Likewise, 34 percent of veterans with a mental health need who use VA services indicated they are very or somewhat dissatisfied with the time between their appointment request and the actual appointment. For more details on these findings, see Chapter 6, Table 6-17.

The VA’s Veterans Satisfaction Survey (VSS), an annual survey of veterans served by the VA, also asks veterans about mental health care appointments. For example, using a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 is strongly disagree, 5 is strongly agree, and 3 is neither, veterans were asked to rate the statements, “I can get appointments with my mental health provider on the day that I want or within two weeks of the day I want,” and “My mental health provider and I agree on how often I should I have appointments.” For FY 2016,2 the VA reported a mean rating of 3.84 (standard deviation [SD] = 1.25) and 3.99 (SD = 1.02) (VA, 2016e), respectively, for OEF and OIF respondents, which possibly suggests some agreement with these statements. (See Chapter 15 for details about the VSS.)

On the committee’s site visits, veterans frequently expressed high levels of frustration with the VA scheduling system, with comments that reflect some of the complexities described above. Specifically, many veterans were unhappy that they could not choose appointment times that work for them.

You get [your appointment] in the mail and you have to go to the appointment. . . . The VA is like, “Oh, we’ll see you in 3 months. Here’s the date and time and you have to be there.” [Cleveland, Ohio]

VA clinicians also remarked on veterans’ frustrations and their own frustrations with the scheduling system. One reported,

They decide when your appointments are. . . . You get this letter in the mail, and either you make it or you cancel it. . . . After two missed appointments, they drop you from mental health. [Temple, Texas]

Cancellations and Missed Appointments

Cancellations by the VA (not the veteran) were a problem reported by numerous veterans on the committee site visits. This was exacerbated in those situations when veterans took time off of work or lined up a babysitter, traveled to the VA facility, sat for hours in the waiting room, only to find out that the appointment had been canceled. One veteran from Cleveland, Ohio, noted, “My second appointment, the doctor canceled, didn’t tell me. I showed up and I sat there for an hour and a half. The third appointment, the doctor canceled, nobody told me. I sat there for 45 minutes, and went and made a complaint.” This frustration with cancellations was enough for some veterans to discontinue treatment at the VA:

___________________

2 The FY 2016 report reviewed by the committee covers survey data collected through June 2016.

Then someone called and canceled my appointments. Then they rescheduled me without receiving any notice. . . . Then later, “OK, you didn’t show up.” I’ve written off the services here. [Charleston, South Carolina]

Adding further frustration for veterans is the fact that although they will sit in the waiting room for hours waiting for an appointment, the VA may cancel an appointment if the veteran is 10 minutes late. For example, a veteran reported,

I pulled in . . . 45 minutes before my appointment. But by the time I got in there, I was late. . . . My appointment was canceled. It’s just a nuthouse over there sometimes to park your car. [East Orange, New Jersey]

The issue of missed mental health appointments or “no shows” is complex, with differing interpretations of how they occur. From many staff members’ perspectives, veterans’ failure to show up for appointments not only shows a lack of personal responsibility, but contributes to access challenges for other veterans:

Veterans are only going to get better if they take a little bit of ownership for identifying their needs, driving to the VA and getting their ID card, calling the 800 number and making an appointment, canceling their appointment if they can’t go so it doesn’t jam the system for everyone else to try to get an appointment. [Tampa, Florida]

In fact, the site visitors did hear from veterans who admitted they simply had not gone to their appointments:

I have a severe memory issue. . . . I’ve missed a handful of appointments because I didn’t write it down. [Cleveland, Ohio]

But many veterans presented a more complex picture of “no shows” than did the staff. For example, across all 21 site visits, veterans who tried to be responsible reported significant difficulty contacting their providers if they needed to miss or change an appointment:

There’s one number for the VA. You call that number, and you talk with someone, explain to them what your situation is, and then you are transferred. . . . You’re not even told, “I’m transferring you.” You’re just cut off. [Cleveland, Ohio]

I remember calling [my therapist], saying, “I’m trying to call but nobody’s answering.” There’s no voicemail. . . . I called for like a week straight. When I did finally get to somebody, they kept sending me to the wrong departments. It was a mess, so I gave up. [Hampton, Virginia]

The VA has acknowledged the difficulties with the phone system and in 2016 began the VA Medical Center Call Center Expansion (VCCE) project, designed to improve veterans’ access to care through the telephone. Under the program, VAMCs that lack dedicated call centers supporting primary care appointment scheduling, nurse triage, and pharmacy telephone operators were required to establish one no later than December 31, 2016. Since then, the VA has initiated a number of telephone urgent care call center activities to further improve the telephone experience (VA, 2017a).

While the committee completed the site visits before the VCCE was complete, VA staff were often able to corroborate the phone system challenges, noting, for example, that calls to CBOCs often get routed back to the operator at the VAMC.3 Staff members also described days in clinics that are so

___________________

3 Site visit team members often reported similar experiences when calling CBOCs.

hectic that front desk clerks are not able to answer the phone or are too busy to pick up the voicemails. A clinician at a CBOC described what she experienced with one of her patients:

I was present when he [veteran] called to cancel. [Then] I happened to be in his chart for something and it said “no-show,” and so I actually called the clinic . . . and they changed it to “Canceled by patient.” I haven’t had those situations often. [Battle Creek, Michigan]

As was suggested above in the discussion about appointment cancellations, some theorize that coding a VA-canceled appointment as a “no show” by the veteran not only puts the onus for the missed appointment on the patient, but also theoretically resets the clock on the 30-day window. While the exact causes of the “no show” problem are not clear, there is general agreement that the VA could accommodate more veterans—and accommodate them more quickly—if the problem of unfilled appointments could be resolved.

At numerous sites, veterans described appointment cancellations by the VA that appeared to be happening so frequently as to be systemic. The following quotes are illustrative:

I was standing in front of him [receptionist], and he insisted. He told me three times it was canceled by patient. I was getting worked up, so he dug into the computer a little more and saw it was canceled by therapist. [El Paso, Texas]

They’ll call you sometimes and be like, “Oh, your appointment was canceled.” Then next appointment is another 3 months from that date. Then it’s 6 months before you’re seen. [Hampton, Virginia]

One vet center staff member—also a veteran—described her most recent experience with appointment cancellations and offered her own explanation for the pattern:

February 2nd I had a specialty care clinic for my service-connected disability canceled. Rescheduled February 25th. The day of, canceled. Rescheduled March 6th. Canceled. Rescheduled. If you cancel me, if we’re 30 days out, the clock restarts, and it’s not picked up on the system list [emphasis added –El Paso, Texas].

Shorter Appointments, Longer Intervals Between Them

Another strategy to meet the demand and shorten wait times is to shorten the actual appointment time. Many veterans are aware that systemic strains are the reason for the brevity of appointments, and they frequently described appointments with clinicians that felt too brief to be of any value, either to the clinician (who might want a little more information) or to the veteran (who might want to share a little more). The following quote is illustrative and reveals that veterans are aware that systemic strains are the reason for the brevity:

I felt like I was being rushed, because there were a lot of people there. . . . It’s like they have a quota, and they have to receive certain people at certain times. . . . She didn’t say she would talk to me about it, because obviously she’s not going to be my psychiatrist. She said, “Somebody will do something about it, later on.” . . . I haven’t been back since. [Charleston, South Carolina]

While shortening appointments may get more people seen on a given day, many providers reported that the intervals between appointments are longer than they would clinically recommend. The following quotes illustrate VA staff members’ concerns about this.

Their appointments are too far spread, especially for mental health. . . . They said, “We don’t have that capacity to do weekly appointments. We can see you once every 3 weeks.” [Temple, Texas]

I think it’s hard for me to feel like I’m providing good patient care when I can only see someone once a month for therapy. [Topeka, Kansas]

While shorter appointments and longer intervals between them may make it possible to get more veterans seen at a facility, many clinicians whom the committee heard from raised questions about the clinical ramifications of the strategy.

Extended Hours

Many veterans noted that the VA service hours (typically 8:30 a.m. to 4 p.m.) are the same as their work and school hours, making it difficult to schedule appointments that don’t conflict with other commitments. One veteran in Altoona, Pennsylvania, said, “If you’re at work, we’re at work, too. When you’re off work, that’s when we’re off.” Although many VA facilities have recently worked to expand hours, these expanded hours are not without significant challenges.

Some VA locations offer extended hours and weekend appointments, which has been met with mixed success. Staff reported that extending the hours and offering a “drop-in” approach has not been particularly successful. The following comment from a provider at a CBOC is illustrative of this experience:

Our substance abuse groups on Tuesday evenings and Saturdays have not gone over well. . . . The groups during the day will have 15 veterans, sometimes up to 20 even, and maybe 2 or 3 on a Saturday was a good group. [Iowa City, Iowa]

Interestingly, several veterans interviewed during the site visits said that they preferred getting counseling services at the vet centers because the centers regularly offer evening and weekend hours during which time they can receive individual counseling or attend a group session. And a provider in Biloxi who said her extended hour appointments were full, offered this suggestion:

. . . . if you’re doing your own scheduling, . . . if you’re making a clinical decision about who you offer those slots to, . . . that makes a big difference. [Biloxi, Mississippi]

Another success story involved an evening skills and education group for spouses:

The course we’re mainly teaching now, it’s NAMI Homefront, . . . which is a 6-week family psycho[logical] ed[ucation] course. . . . We do all sorts of marketing. Not just Facebook. We do newspaper. We do TV. We’ll do radio. The grant money and the support of our leadership here [allow us] to get food, so we serve a dinner. They’re here . . . because they’re so desperate for information. We engage them. [Syracuse, New York]

When asked why she thought this approach had been successful, the staff member identified the strong marketing effort and the fact that participants are provided with a meal. And yet a colleague of this interviewee, during the same group discussion, reported having tried to offer a substance use disorder treatment group in the evenings—complete with dinner—with no success at all. Despite the tendency for appointments during extended hours to go unused, VA staff continued to discuss ways to improve service access for veterans with busy lives.

PROGRAMS TO IMPROVE TIMELY ACCESS TO CARE

The VHA has employed a number of strategies and programs designed to help make care more accessible to veterans both within the VA and in the broader community, using non-VA providers. This section describes some of these strategies and programs.

Improving the VistA Scheduling System

VistA, the VA’s information technology platform implemented in the early 1980s, includes applications for clinical, financial, administrative, and infrastructure needs in a single database that is used throughout the VA system. However, as discussed earlier in this chapter, inefficiencies in the VistA scheduling system are contributing to longer-than-necessary wait times. The congressionally appointed Commission on Care recently called the VistA system “antiquated, highly inefficient” and said it “does not optimally support processes or allow for efficient scheduling of appointments” (Commission on Care, 2016). It is also very expensive to maintain—85 percent of the VA’s total information technology budget is devoted to systems operations and maintenance (Commission on Care, 2016). Most VAMCs have customized their local versions of VistA—there are approximately 130 versions across the system—which further complicates maintaining and operating the system (Commission on Care, 2016). In 2015, the VA rolled out VistA Scheduling Enhancements (VSE), which introduced a graphical interface designed to increase scheduler efficiency, improve usability, and decrease the amount of time it takes to schedule an appointment (VA, 2016d). The improvements allow schedulers to view all the providers’ scheduling grids to better use scheduling opportunities (VA, 2017b). Additional enhancements to the VistA graphical interface, including integration with the Veteran Appointment Request mobile application (discussed below), are also planned.

Despite these improvements, VistA remains an exceedingly complex system. The VSE user guide is nearly 200 pages in length (VA, 2016d), and the enhancements fail to address the system’s inability to capture accurate clinical use data, leaving administrators, managers, and planners without the information they need to effectively manage the supply of clinical slots (Commission on Care, 2016).

In another attempt to improve the scheduling process, the VA rolled out a mobile application called Veteran Appointment Request (VAR) which allows veterans to schedule appointments from their smartphones, tablets, or through the Web on a home computer. The app allows users who are receiving care from either a VAMC or CBOC to schedule and request primary care appointments and request mental health appointments (VA, 2016b). VAR and other mobile technologies are described in greater detail in Chapter 14.

VistA Scheduling Enhancements and VAR were initially designed to be short-term solutions. As a long-term approach, the VA awarded a $624 million contract to Epic Systems and Lockheed Martin in August 2015 to supply and implement a commercially available medical appointment scheduling system to integrate within VistA scheduling. The system includes Epic Cadence (a medical scheduling product) and My Chart (a patient portal for self-scheduling). This system is currently in the pilot phase, and the VA plans to implement it in one location in 2018. An evaluation of that localized implementation will help determine plans for national deployment.4

___________________

4 Personal communication with Stacy Gavin, VA Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, 2017.

Timely Access to the Veterans Crisis Line

The Veterans Crisis Line (VCL) is a confidential service to help veterans and active-duty service members (and their friends and family) work through a suicidal or self-harm crisis. VCL was launched in 2007 and since then has answered over 2.9 million calls from veterans, service members, and their friends and family members (VA, 2017b). The VCL is accessible via a toll-free number (launched in 2007), text message (launched in 2011), or over the Web via online chat (launched in 2009) (VA, 2016c). The chat service has answered over 350,000 requests; the text messaging service has answered nearly 73,000. VCL staff has sent nearly 474,000 referrals to local VA suicide prevention coordinators on behalf of veterans (VA, 2017b).

VA has campaigned extensively to raise awareness about the VCL. Karras et al. (2016) reported on patterns of VCL use associated with a VA VCL awareness campaign that ran for 7 months in 2009. The campaign was associated with a small (but significant) increase in daily calls to the VCL, demonstrating that the VA’s awareness campaign was effective at increasing traffic to the VCL, potentially preventing suicides that otherwise may have occurred.

There is some evidence, however, that VCL has had problems providing timely access to its service. In 2015 the GAO reviewed how well the VA was meeting its response-time goals for the VCL, how the VA was monitoring VCL call center operations, and how the VA was working with VCL service partners to ensure that veterans received high-quality service (GAO, 2016b). Perhaps the most worrisome finding concerned the reliability of the text messaging system. To test the system, the GAO sent 14 text messages to the VCL; four of the messages went unanswered. The VA informed the GAO that it did not monitor the text messaging system itself. Rather, the VA was relying on its third-party text messaging provider for all aspects of the text messaging system, including testing, and was not aware of any problems. The provider informed the GAO that it has no routine testing system in place. Similarly, the VA reported to the GAO that there were no standard benchmarks for response time for either text messages or online chats. The GAO recommended that the VA set performance indicators for these modalities and routinely test the text messaging system.

The GAO also tested wait times for accessing the VCL via telephone and found some problems. The test found that 73 percent of calls were answered within 30 seconds and 99 percent of calls were answered within 120 seconds, results that were similar to the VA-reported data from 2015 but that fell short of the VA’s goal of answering 90 percent of calls within 30 seconds. Calls not answered within 30 seconds were routed to a backup call center although responders there did not have access to veterans’ electronic medical records of those enrolled in VA care, did not have the same training as the primary VCL providers, and had no way to send caller data to the main VCL center (making follow-up impossible). To help improve caller wait times, the VA established a center evaluation team to monitor performance of the VCL and to make changes if necessary. Other recent improvements include data-driven scheduling to match demand, the employment of more responders, and the adoption of new procedures to quickly reroute callers who are not in crisis. Updates to the telecommunications infrastructure were also under way in 2016. VA officials also told the GAO that by summer 2016 supervisors would have access to real-time performance data to track the workload and performance of responders (GAO, 2016b).

Despite these efforts, there were allegations in 2016 that the VCL management was still facing problems as the call response times had gotten worse, not better (Kime, 2016a). Reports indicated that up to half of calls in May 2016 were not answered within 30 seconds and were rerouted to the backup call center—where providers did not have access to patient records, had received less training than providers in the main call center, and had no way to share caller data with the VCL providers for follow-up. Calls were being rerouted because some VCL providers were leaving their shifts early, refusing to go to the building they were assigned to, and answering as few as one to five calls per day.

Recent efforts to improve the VCL include a hiring surge and expansion to a second VCL site in October 2016 in order to double capacity as well as the implementation of a workforce-management system and of a quality management program (VA, 2017b). In April 2017 VA Secretary David Shulkin announced in a press release that less than 1 percent of calls to the VCL were being rerouted to backup centers (VA, 2017d). While lawmakers commended this improvement, they also cautioned that other improvements were still needed, such as filling the director’s position at the Veterans Crisis Line (Ogrysko, 2017). Similarly, the GAO (2017b) and the VA Office of Inspector General (2017a) have both recently identified continuing problems related to wait times, leadership, and performance monitoring and highlighted past recommendations that still have not been addressed.

Community Care

The VA has a long history of contracting with non-VA providers to serve veterans that need care that the VA is unable provide due to limited resources, unacceptable wait times, or geography. These programs, which have evolved and grown in recent years, are overseen by the VA Office of Community Care. In FY 2016, community care accounted for about 16 percent of VA’s medical care obligations.5 Recent legislative action—most notably the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act6—has allowed the VA to greatly expand the use of community care to improve access to services—including mental health services—for veterans. In 2014, 20 percent of all VA users utilized some community care. Community care for mental health, however, has been less utilized. In 2014, only 2.3 percent of veterans’ mental health visits involved non-VA providers (RAND, 2015a). VA community care programs include Traditional Community Care, Patient-Centered Community Care (PC3), and the Veterans Choice Program (VCP). However, recent legislation (Surface Transportation and Veterans Health Care Choice Improvement Act of 2015)7 has directed the VA to consolidate all community care programs under the VCP umbrella, and the VA has submitted a draft plan to do so. As of July 2016, nearly all community care was provided under the VCP (GAO, 2016c). This section will discuss community care provided through PC3 and VCP, the administration of the programs, and the questions that remain about VA oversight and quality monitoring of the care provided via community care.

Patient-Centered Community Care (PC3)

While it will ultimately be combined with the VCP, PC3 is a national VA program to provide eligible veterans access to certain medical care (including primary care) when the veteran’s local VA facility cannot provide the needed service due to long wait times, lack of a needed specialist, or long travel distance. For a veteran to receive purchased care through the PC3 program, the veteran’s provider must first determine that the needed care is not available at the local VAMC. The Non-VA Medical Care Office then must authorize the veteran to obtain care through PC3. The veteran should then be contacted by the regional third-party contractor (Health Net Federal or TriWest Health Care Alliance) within 5 days to set up the appointment with the PC3 provider. After the appointment is made, the VA sends the veteran’s medical information to the PC3 provider. Following the appointment, the PC3 provider must return the veteran’s health record to the VA within 14 days (outpatient) or 30 days (inpatient) (VA, 2015a).

___________________

5 Personal communication with Stacy Gavin, VA Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, 2017.

6 Public Law 113-146.

7 Public Law 114-41.

Two 2015 reports by the VA Office of Inspector General looked at the implementation of PC3 (VA Office of Inspector General, 2015a,b). Neither report was specific to mental health services, but both looked at overall systemic issues in the program. One report noted that utilization of PC3 in 2014 fell short of expectations. The VA had projected PC3 to provide up to 25 to 50 percent of all non-VA care; however, it ultimately only provided 9 percent. VA OIG attributed the less-than-expected utilization to the PC3 administrators failing to establish adequate provider networks (VA Office of Inspector General, 2015a). The other investigation found that VA staff took an average of 19 days to submit authorizations to the PC3 contractors and a high proportion of authorizations were then returned to the VHA for being incomplete, further delaying care (VA Office of Inspector General, 2015b). In both reports VA OIG asserts that the VHA does not have effective systems in place to oversee the implementation and surveillance of the program (VA Office of Inspector General, 2015a,b). As noted above, however, community care programs are being consolidated under the VCP and most veterans in need of community care are now referred to the VCP if they are eligible for it, rather than PC3. For example, in FY 2016, there were only 511 mental health authorizations for PC3, compared to 47,109 for VCP.8

The Veterans Choice Program

In response to the health care access issues facing the VA, including excessive wait times for appointments, Congress passed the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 20149 (Choice Act).10 The Choice Act provided new authorities, funding, and other tools to help improve access to care for veterans using the VA system, and it expanded the services provided under PC3. A crucial part of the Choice Act is the Veterans Choice Program, which allows veterans to seek care outside the VA system from an eligible provider if they meet one of several criteria, including that the veteran cannot schedule an appointment within 30 days of their clinically necessary date or that the driving distance from the veteran’s home to the nearest VA facility with a full-time primary care physician is more than 40 miles. If a veteran needs a service that is offered at a VA facility that is more than 40 miles away from the veteran’s home, but there is a VA facility within 40 miles with a primary care physician but does not provide the needed service, the veteran is not eligible to use the Choice Program as the law is currently written (despite the needed service being more than 40 miles away). The VA has stated that a statutory change is required to change the eligibility requirement regarding distance to needed service (rather than nearest facility) (VA, 2015c).

The GAO reported in 2017 that through FY 2016, 55 percent of veterans who used the VCP did so because the service they needed was unavailable at a VA medical facility; 35 percent of those who used the program did so because of a greater than 30-day wait time for an appointment at a VA facility; and 10 percent of veterans who used the program did so because they lived more than 40 miles away from a VA facility or faced another travel burden (GAO, 2017c).

In 2017, the Veterans Choice Program Extension and Improvement Act was signed into law11; it allows the VCP to continue until the $10 billion allocated for the program is depleted. The bill also streamlines the payment process. An additional $2.1 billion was authorized for the VCP with the signing of the VA Choice and Quality Employment Act of 2017.12

___________________

8 Personal communication with Stacy Gavin, VA Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, 2017.

9 Public Law 113-146.

10 The Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014 was further amended by the Department of Veterans Affairs Expiring Authorities Act of 2014 (Public Law 113-175).

11 Public Law 115-26.

12 Public Law 115-46.

In 2017, the VA reported that there were 500,000 community providers eligible to provide care under the VCP or PC3 (VA, 2017c). In FY 2016, 22,077 mental health providers were in the VCP and PC3 provider network. Under a VCP agreement, providers must accept Medicare rates for reimbursement (VA, 2014b). Providers must maintain the same or similar credentials as VA providers and must submit claims to the VA for reimbursement. As the law was originally written, providers were required to submit patient records with their claims (within 14 days for outpatient, 30 days for inpatient, and 24 hours for critical care) so the VA could incorporate them into the veteran’s electronic medical record (VA, 2014c). To speed up the reimbursement process, the VA abandoned this requirement in 2016 (Kime, 2016b). However, slow processing is still an issue as the VA reported in 2017 in that it takes more than 30 days to process 20 percent of “clean” claims (VA, 2017c).

As the VCP has evolved since its inception, a number of legislative and policy changes have been implemented to improve access to care. Patient and provider eligibility requirements have been eased, increasing the pool of both patients and providers eligible to participate. Additionally, third-party administrators are now embedded in some VA facilities to help make veteran participation more seamless. Provider authorization requirements have also been eased (McIntyre, 2016). Originally, providers had to request an authorization (for both PC3 and VCP) before every episode of care. Authorizations now last for up to 1 year from the date of the first appointment. The VA has issued over 3 million authorizations, over 8.7 million appointments have been completed, and it has served over 1.6 million unique veterans under VCP (VA, 2017e). In FY 2016, the VA issued 47,109 authorizations for mental health under VCP to 33,199 unique veterans. This is a dramatic increase from FY 2015, during which the VA issued 7,597 authorizations for mental health to 6,307 unique veterans.13

Other elements of the Choice Act designed to improve access to care for veterans include an extension of Project Access Received Closer to Home and the Assisted Living Pilot Program, an expansion of mobile vet centers and mobile medical centers, and outreach to the Indian Health Service. All of these efforts were designed to improve access to populations with limited access to VA services, such as rural populations, veterans with traumatic brain injury, or Native American veterans (VA, 2014c).

The Choice Act also mandates new third-party assessments of VA services, the creation of a “technology task force” to review VA patient scheduling processes, the lease of new medical facilities, the creation of new facility-specific wait-time data (which will be publicly available), new staffing requirements, and expanded military sexual trauma counseling and care (VA, 2014c).

While VCP is intended to expand access to veterans, there is some concern that many community mental health providers may not be equipped to serve the unique needs of veterans, particularly those with service-connected needs (Martsolf et al., 2016). In a survey of non-VA providers, RAND found that only 13 percent of respondents were “ready” to deliver culturally competent, high-quality mental health care to veterans and their families (Tanielian et al., 2014). Respondents completed a series of questions related to cultural competency, training for and use of evidence-based practices, practice settings and proximity to military and VA facilities, and prior experience in VA or military settings. Only 23 percent of those practicing within 10 miles and only 15 percent of those practicing more than 10 miles from a military facility demonstrated high military cultural competency. Only 35 percent of psychotherapists reported that they were trained and had received supervision in the delivery of at least one evidence-based practice for both PTSD and depression. Licensed counselors were best equipped to deliver evidence-based practices for PTSD and depression, but still less than half of the respondents met the RAND criteria.

___________________

13 Personal communication with Stacy Gavin, VA Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, 2017.

While questions about the quality of community providers are legitimate concerns, the committee’s survey results showed that users of non-VA mental health services and users of VA mental health services both positively rated their experiences with providers. While the responses among the two user groups were similar, non-VA mental health users rated their experiences slightly higher across the four domains included in the survey. For example, 76 percent of non-VA mental health users strongly or somewhat agreed that their mental health provider understood their background and values. Among VA users, 69 percent somewhat or strongly agreed with that statement. Among non-VA mental health users, 89 percent reported they never had a hard time communicating with their provider; among VA mental health users, 75 percent reported they never did. Other domains, such as “I feel welcome at my mental health provider’s office” and “my mental health provider looks down on me and the way I live my life” were similar among VA mental health users and non-VA users, but non-VA users did rate their experiences slightly more favorably than VA users did. It should be noted though that the non-VA providers the respondents are referring to in survey are not necessarily VCP providers (although it is possible that some of them are).

Another report by RAND found that about half of those who live more than 40 miles away from the nearest VA facility also live more than 40 miles from the nearest non-VA mental health care provider (RAND, 2015a). This illustrates the overall shortage of mental health providers in the U.S. health care system, particularly in rural areas (see Chapter 8 for an expanded discussion on this topic). It also indicates that because of the overall mental health care provider shortage and the uneven distribution of providers, the VCP may not improve access to mental health care for many veterans living more than 40 miles from a VA facility.

The GAO looked at the scheduling process and timeliness of routine and urgent care provided under the VCP (GAO, 2017c) and found that if the maximum allowable time to schedule appointments is used throughout the process, a veteran can wait for up to 81 days to receive care through the VCP. However, the VA cannot calculate actual wait times that veterans have experienced under VCP, because it does not collect all the data it needs to do so. The data the VA does collect begin at the moment a veteran schedules an appointment with the third-party administrator, but the data do not capture the time it takes a VAMC to send third-party administrators the referral or the time that passes while the third-party administrator attempts to contact the referred veteran. The GAO reviewed 55 routine care authorizations and found VAMCs took an average of 24 days to send the VCP referral to the third-party administrator, who in turn took an average of 14 days to accept the referral and confirm with the veteran they wanted to opt in to the program. After appointments were scheduled, an average of 26 days elapsed before the actual appointment occurred. VA wait-time data only include the time between the appointment scheduling and the actual appointment. The GAO did a similar analysis of a sample of urgent care authorizations and found similar wait times at each of the stages of the process. In 2015, RAND highlighted many of these same data insufficiencies and recommended that the VA improve data collection related to community care to improve processes and outcomes for veterans (RAND, 2015b).

As the use of VCP expands, the VA faces several challenges to ensure that community care best serves the veterans that utilize it. For example, coordinating and managing the care veterans receive via community care providers poses a challenge, especially since the requirement for providers to submit patient records with their claims was abandoned in 2016 (Kime, 2016b). While the program is being phased out, PC3 in particular has been criticized for lacking the necessary measures to appropriately coordinate veterans’ care (RAND, 2015b). One barrier to effective coordination of care is the inability to seamlessly pass patient records electronically from the VA to community providers and back. Few community providers meet the technical requirements needed to meet federal standards for secure exchange of health information (RAND, 2015b). RAND reported in 2015 that electronic record sharing

with non-VA providers was a rare occurrence: nearly half (47 percent) of facilities reported they share records electronically with non-VA providers “none of the time” and 39 percent said they do it “some of the time” (RAND, 2015b).

Site Visit Findings Regarding the Choice Program

Despite numerous veterans’ reports of not being able to get into care in a timely fashion, VA staff generally indicated that they are not referring veterans via the VCP. While the site visits were completed during the first year of the VCP, providers offered several explanations for this, one of which was the belief that non-veteran providers will not be able to offer services that are appropriate for the veteran population, as was described in Chapter 8 in the discussion about quality of care. But even providers who are willing to refer veterans to the community reported not using VCP because of its unwieldiness:

I’ve heard a lot of complaints about the Veteran’s Choice program . . . they’re told on the other end, “Oh, you don’t qualify because you live too close,” or, “You have a VA facility somewhere else that can do this.” [Battle Creek, Michigan]

[F]ee-basis has now gone away, and the Choice Program exists, which is actually not been beneficial . . . because there are so few Choice providers. . . . It’s been a very difficult process for us to digest, knowing that we’ve got to figure out a way to get these patients care. [Denver, Colorado]

[It] is almost impossible to get referrals to anybody through that [Choice]. I got a veteran this morning that wants to do hypnotherapy. I called Choice, and I said, “I’m a provider. I’m looking to see if I can find a provider in the community that will do hypnotherapy.” He said, “Wait a minute. I can help you with that.” He gets back on the phone, and then he says, “No. You have to call your local VA to get a provider list of those resources.” I am the local VA! [Seattle, Washington]

Instead of using Choice, providers who refer veterans to the non-veteran sector reported taking advantage of a variety of resources to support their clients’ needs. In most locations, VA staff reported making referrals to their local vet centers. As noted earlier, the vet centers are funded by the VA, but they operate separately from the VAMCs and CBOCs. Consistent with that separation, in a few locations VAMC staff indicated little to no awareness of the availability of vet center resources. Veterans, too, reported looking for assistance at vet centers.

Third-Party Administrators

Since 2013, VA community care programs have been managed by two third-party administrators—TriWest and Health Net. The two entities are responsible for developing regional networks of providers, verifying that providers are appropriately credentialed, licensed to practice in their states, and eligible to participate in federally funded health care programs. They are also responsible for entering into agreements with providers and processing payments to providers for their services, and scheduling appointments with veterans (after receiving referrals from the VA). It should be noted that under certain circumstances,14 the VA can enter into direct agreements (“VHA Choice provider agreements”) with VCP providers, bypassing the third-party administrators.

___________________

14 VHA Choice provider agreements are permitted under several circumstances. For example, when no network provider is available for the requested service; when the veteran requests a provider that is not in the contractor’s network; when the contractor was unable to contact the veteran; and when the contractor could not schedule the needed service within the required time frame.

A recent GAO report (GAO, 2016c) examined the credentialing procedures for both TriWest and Health Net and the VA’s oversight of the contractors. In an effort to quickly build a network of eligible providers, the VA deliberately made the credentialing process far less rigorous for VCP than it is for PC3. The credentialing process for VCP typically takes 5 to 10 days, versus 90 days for PC3. To participate in VCP, third-party administrators must verify that providers hold an active, unrestricted license in the state where the VCP service will be performed; have a national provider identification number; have a Drug Enforcement Agency number to prescribe controlled substances; are not excluded from participating in federally funded health care programs; and participate in Medicare. Providers must verify these credentials annually. In addition to the VCP requirements, PC3 providers must also hold board certification (for certain specialties) and verify their education and training, employment history, malpractice history, and malpractice insurance. The VA’s draft plan to consolidate all community care programs under the VCP specified that once the consolidation occurs, the contractors’ credentialing processes will be accredited by a national organization and follow accreditation standards (GAO, 2016c).

The GAO’s review of contractors’ accreditation processes found that both TriWest and Health Net complied with accreditation procedures for PC3. The procedures were well documented in written policies and included quality assurance mechanisms to monitor and spot-check procedures. On the other hand, for VCP, the GAO found that contractors did not always verify credentials and in some cases could not produce documentation that demonstrated that verification occurred. The review also found that the VA lacked a comprehensive system to oversee verification compliance among both contractors. The GAO found that the VA’s monitoring is generally limited to independent reviews of physician’s credentials, but does not include oversight of the contractors’ processes (GAO, 2016c).

As part of the 2015 independent of VA health care delivery, RAND examined community care, including third-party administrators, in depth (RAND, 2015b). While the assessment took place at a time of transition in the community care environment (the VCP was just beginning), RAND made a number of recommendations for the VA to consider to improve community care. Among them, it recommended that the VA evaluate the performance of the third-party administrators, as well as the adequacy of the provider networks, the claims processes, and veterans’ experiences with the contractors and the services they receive through them. It also recommends that contracts with third-party administrators (and providers) should include requirements for data sharing, quality-of-care reporting, and care coordination between providers, third-party administrators, and the VA.

PRACTICES TO FACILITATE TIMELY ACCESS

In addition to the programs discussed above, the site visit interviews revealed several ways veterans can obtain easier and more timely access to services. Veterans who have received either formal or informal assistance navigating the VA system report that they are able to receive care with relative ease. Furthermore, veterans who present with acute mental health needs are also, understandably, given priority.

Navigators and Case Managers Facilitate Timely Access

Veterans and VA staff alike described the challenges working through a massive organization like the VA, which can frustrate even the most seasoned case manager, let alone a veteran with cognitive challenges from PTSD or traumatic brain injury. Veterans described their frustrations in having to fill out forms multiple times because the originals had gotten lost, “being treated like a number,” and waiting for “someone” at the VA to call them for an appointment. Said one veteran in El Paso, Texas, “Make [the VA] easier to get through, and make it easier to navigate. Less bureaucracy, that would do it, less

bureaucracy. . . . At least give us a map or something. That would be nice.” Not surprisingly, veterans who had had help navigating the system reported being able to get into VA mental health services with little or “no trouble at all.” Some had formally appointed navigators, such as veterans who had been discharged from active duty as a result of a medical condition. Many had been in military treatment facilities or warrior transition units (WTUs) while awaiting separation, and all had been assigned case managers while in these units. These military case managers were identified both by veterans and VA staff as having served as liaisons with case managers at the VA, thus being able to facilitate the veteran’s transition between the Department of Defense and the VA. A clinician in Charleston, South Carolina, similarly pointed out the critical role played by navigators: “Unless they’re attached with WTU, oftentimes they do fall between cracks.”

Other veterans who reported relatively easy access indicated having informal navigators, including family members who worked for the VA, other veterans who were serving formally or informally as peer supports, and navigators working for state-sponsored veterans’ programs, such as those in Virginia, Connecticut, and South Carolina. A staff member in one of these state-run programs said, “Our goal is not to get in front of anyone else [waiting for VA services], but to help a vulnerable population get what they need.” And a veteran who had help from a military chaplain similarly commented on how such assistance is vital to being able to access care:

The chaplain was able to get me in here . . . within 24 hours. . . . I don’t know that I could have done that on my own, because I tried. The fact that it needs that is, I think, problematic. [Hampton, Virginia]

Managing Acute Distress

A second category of veterans who appear to gain timely access to VA services are those who present at a VA facility in acute distress, that is, those whose conditions indicate the potential for imminent harm to themselves or others (for example, in the case of psychiatric crisis or homelessness). VA staff reported that often these veterans will enter the system through the emergency room, but many VAMCs also have walk-in clinics where a veteran in crisis can be seen by a clinician immediately. Veterans themselves said that the system is geared more toward dealing with crises than with someone whose level of suffering is sub-acute. Said one veteran:

As soon as I [moved] here it was the initial, “Are you going to hurt yourself? Do you feel you’re going to hurt others?” No, I have no intentions of going and hurting myself. That seems to be where it stops. Everybody, they’re worried about those top three questions. [Altoona, Pennsylvania]

Although most veterans interviewed by the site visitors indicated they did not want to ask for help (much less express suicidality), one provider in Nashville suggested that the presentation of a crisis may be some veterans’ only way into care: “I know a lot of them have expressed suicidal ideations just so they can get an appointment, and that’s not how they feel. They’re not actually suicidal.”

Select Community-Based, Non-VA Services

During the site visits conducted as part of this study, VA clinicians reported referring clients to Give an Hour, an organization through which private clinicians donate their time to provide services to veterans.15 Interviewees also indicated that they were referring their clients out on a fee basis to community providers (despite some conflicting information about whether they could do that with the

___________________

15 See https://www.giveanhour.org (accessed January 7, 2018).

implementation of Choice). Veterans reported looking for assistance outside of the VA health system, including through peer groups in the community (for example, 12-step groups for combat veterans with PTSD and women veterans’ support groups). Numerous community-based organizations offer an array of activities for veterans. These include recreational outings (for example, fly fishing, hunting, and square dancing), volunteer opportunities (for example, Team Red, White, and Blue and Feed Our Vets), service dog training, job skill development (for example, culinary training), wellness services (for example, acupuncture, meditation, and yoga), peer outreach and engagement, and various college-based student veteran organizations. Most of these organizations do not provide veterans counseling services with a licensed therapist. Nevertheless, and consistent with the treatment aims of the VA, veterans are getting opportunities to step out of their isolation and engage in positive social activities with other veterans.

SUMMARY

Using information from the committee’s survey, site visit, and literature research, this chapter examined the issues affecting timely access to mental health care services at the VA. A summary of the committee’s findings on this topic is outlined below.

- Timely access to mental health care is variable across VA facilities.

- Wait-time data from the VA’s internal monitoring system underestimate reported wait times because they track wait times from the veteran’s preferred date, not the initial request for services.

- The VA has begun efforts to ensure that same-day mental health appointments are available throughout the system.

- While improvements to the scheduling system are currently being implemented, the VA’s current VistA scheduling system contributes to unnecessary delays in care.

- Both veterans and providers reported a variety of frustrations and concerns regarding unexplained appointment cancellations and short appointments.

- Some providers reported that intervals between appointments are often longer than they would clinically recommend.

- A majority of veterans indicated that an easier appointment process was an important change the VA could make.

- While the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014 allows eligible veterans who meet certain conditions to seek care outside of the VA, non-VA community mental health providers are in short supply in many areas and may lack the training and expertise to deliver high-quality care for conditions such as PTSD.

- The network of mental health providers providing care under the Veteran’s Choice Program is expanding; however, sharing medical records between the VA and community providers and the coordination of care for veterans who are using the Veteran’s Choice Program continues to be a challenge for the VA to manage.

- Navigators and case managers facilitate access to mental health care at the VA; however, these resources are limited and are not available to all veterans.

- While efforts to improve the VistA scheduling system have begun, it is unclear if they are adequately addressing certain problems, such as capturing the necessary data to maximize clinical efficiency.

REFERENCES

Commission on Care. 2016. Final report of the Commission on Care. Washington, DC: Commission on Care.

GAO (Government Accountability Office). 2012. VA health care: Reliability of reported outpatient medical appointment wait times and scheduling oversight need improvement. Washington, DC: Government Accountability Office.

GAO. 2013. VA health care: Reported outpatient medical appointment wait times are unreliable. GAO-13-363T. Washington, DC: Government Accountability Office.

GAO. 2014. VA health care: Ongoing and past work identified access problems that may delay needed medical care for veterans. GAO-14-509T. Washington, DC: Government Accountability Office.

GAO. 2015. VA mental health: Clearer guidance on access policies and wait-time data needed. Washington, DC: Government Accountability Office.

GAO. 2016a. VA health care: Actions needed to improve access to primary care for newly enrolled veterans. Washington, DC: Government Accountability Office.

GAO. 2016b. Veteran Crisis Line: Additional testing, monitoring, and information needed to ensure better quality service. Washington, DC: Government Accountability Office.

GAO. 2016c. Improved oversight of community care physicians’credentials needed. Washington, DC: Government Accountability Office.

GAO. 2017a. High risk series: Progress on many high-risk areas, while substantial efforts needed on others. Washington, DC: Government Accountability Office.

GAO. 2017b. Veterans Crisis Line: Further efforts needed to improve services. Washington, DC: Government Accountability Office.

GAO. 2017c. Veterans health care: Preliminary observations on veterans’ access to Choice Program care. Washington, DC: Government Accountability Office.

Hepner, K. A., S. M. Paddock, K. E. Watkins, J. Solomon, D. M. Blonigen, and H. A. Pincus. 2014. Veterans’ perceptions of behavioral health care in the Veterans Health Administration: A national survey. Psychiatric Services 65(8): 988–996.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2014. Treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder in military and veteran populations: Final assessment. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2015. Health care scheduling and access: Getting to now. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Karras, E., N. Lu, G. Zuo, X. M. Tu, B. Stephens, J. Draper, C. Thompson, and R. M. Bossarte. 2016. Measuring associations of the Department of Veterans Affairs’ suicide prevention campaign on the use of crisis support services. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 46(4):447–456.

Kime, P. 2016a. VA crisis line director resigns, text messages go unanswered. http://www.militarytimes.com/story/veterans/2016/06/29/va-crisis-line-director-resigns-text-messages-go-unanswered/86519866/ (accessed October 12, 2016).

Kime, P. 2016b. VA eases method for paying choice doctors; senators remain skeptical. http://www.militarytimes.com/story/military/benefits/veterans/2016/03/04/va-eases-method-paying-choice-doctors-senators-remain-skeptical/81313982/ (accessed April 26, 2016).

Martsolf, G. R., A. Tomoaia-Cotisel, and T. Tanielian. 2016. Behavioral health workforce and private sector solutions to addressing veterans’ access to care issues. JAMA Psychiatry 73(12):1213–1214.

McIntyre, Jr., D. 2016. Statement of Mr. David J. McIntyre, Jr. to the House Committee on Veterans’ Affairs. March 22, Washington, DC.

Medica. 2016. Appointment access and office wait time. https://www.medica.com/providers/administrative-resources/administrative-manuals/medica-administrative-manual/health-management-and-quality-improvement/appointmentaccess-and-office-wait-time (accessed May 23, 2016).

MITRE Corporation. 2015. Assessment H (health information technology). McLean, VA: MITRE Corporation.

Ogrysko, N. 2017. Lawmakers see progress in veterans crisis hotline, but it’s still far from “fixed.”https://federalnewsradio.com/hearingsoversight/2017/04/lawmakers-see-progress-veterans-crisis-hotline-still-far-fixed/ (accessed May 11, 2017).

Partnership Health Plan of California. 2016. Appointment wait time standards. http://www.partnershiphp.org/Members/Medi-Cal/Pages/AppointmentWaitTimeStandards.aspx (accessed May 23, 2016).

Peach State Health Plan. 2016. Appointment access and availability standards. http://www.pshpgeorgia.com/files/2015/08/PSHP-GA_Appointment-AccessandAvailabilityStandards_ver1_20150826.pdf (accessed May 23, 2016).

Pizer, S. D., and J. C. Prentice. 2011. What are the consequences of waiting for health care in the veteran population? Journal of General Internal Medicine 26(Suppl 2):676–682.

Prentice, J. C., and S. D. Pizer. 2007. Delayed access to health care and mortality. Health Services Research 42(2):644–662.

RAND Corporation. 2015a. Resources and capabilities of the Department of Veterans Affairs to provide timely and accessible care to veterans. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

RAND Corporation. 2015b. Assessment C (care authorities). Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

Superior Health Plan. 2016. Doctor visits—How soon should you be seen?http://www.superiorhealthplan.com/files/2011/11/AppointmentWaitTimesENG.pdf (accessed May 23, 2016).

Tanielian, T., C. Farris, C. Epley, C. M. Farmer, E. Robinson, C. C. Engel, M. W. Robbins, and L. H. Jaycox. 2014. Ready to serve: Community-based provider capacity to deliver culturally competent, quality mental health care to veterans and their families. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

VA (Department of Veterans Affairs). 2014a. Federal register: Wait-time goals of the department for the Veterans Choice Program. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs.

VA. 2014b. Non-VA medical care program fact sheet for interested providers. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs.

VA. 2014c. Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014 (“Choice Act”). Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs.

VA. 2015a. Process for receiving care under PC3. http://www.va.gov/PURCHASEDCARE/programs/veterans/nonvacare/pccc/PC3_for_Vets.asp (accessed September 29, 2015).

VA. 2015b. Uniform mental health services in VA medical centers and clinics. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs.