3

The Veterans Health Administration’s Mental Health Services

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA), which manages the integrated health care system of the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), provides eligible veterans, including U.S. veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, with a comprehensive array of mental health care services in outpatient, inpatient, and residential settings. After enrolling to receive VHA health care, eligible veterans can access these services in several ways. They may walk into a VHA facility and request mental health services. If they are already being seen in primary care, they may receive their mental health services within the primary care setting, if needed, or be referred to specialty care. Vet Centers provide a third pathway into mental health care. Veterans can walk into a Vet Center on their own with or without a referral. Again, should more specialized or acute services be required, Vet Centers can make the appropriate referral to mental health specialty care or primary care. Finally, veterans may enter the VHA health care system via emergency service departments, either at VHA facilities or at civilian hospitals; those seen in civilian emergency service departments may be later referred to VHA health care.

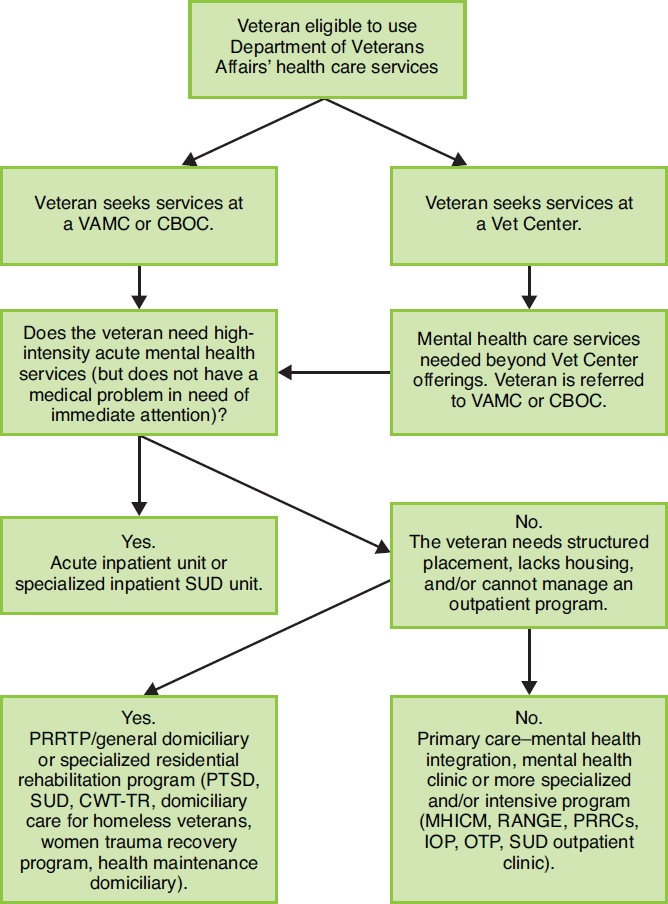

Figure 3-1 depicts an algorithm by which veterans are triaged within the mental health system. For illustrative purposes, the figure reflects a one-way process for the initial placement of a veteran. However, once veterans are receiving mental health care, they move within and between service levels in any direction as need dictates.

Although Figure 3-1 illustrates how veterans are moved through VHA mental health care, it does not reflect the way mental health care services are integrated with the rest of the VHA health care system. Veterans have complete access to medical specialty services as needed. Similarly, veterans receiving medical care can be referred at any time to mental health care if the need arises. To support this fully integrated system of care, the VHA has an integrated electronic medical record documenting all care that is provided, with all providers within the system given complete access to all records, including mental health care records. Given that a large percentage of veterans treated by the VHA have comorbid medical and mental health diagnoses, it would appear to make good sense to provide veterans with a fully integrated medical and mental health system of care.

NOTE: CBOC = community-based outpatient clinic; CWT-TR = compensated work therapy-transitional residence; IOP = intensive outpatient program; MHICM = mental health intensive case management; OTP = opioid treatment program; PRRC = Psychosocial Rehabilitation and Recovery Center; PRRTP = Psychosocial Residential Rehabilitative Treatment Program; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; RANGE = Rural Access Network for Growth and Enhancement; SUD = substance use disorder; VAMC = Veterans Affairs medical center.

In addition to the mental health care services depicted in Figure 3-1, the following teams, specialists, and programs are available to support all inpatient, outpatient, and residential programs:

- Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) clinical teams and PTSD specialists,

- Substance use and PTSD dual diagnosis teams,

- Women’s stress disorder treatment teams,

- Services for returning veterans—mental health teams,

- Health Care for Re-Entry Veterans, and

- Vocational rehabilitation programs.

Also, several programs have been created that specifically target the homeless veteran population: Department of Housing and Urban Development—VA Supportive Housing (HUD-VASH), Health Care for Homeless Veterans, Grant and Per Diem program, and Homeless Veterans Supported Employment Program.

This chapter is intended to be solely descriptive and to illustrate the breadth of programs and services offered by the VA. Evaluating all of the individual programs and services described below is beyond the scope of work. The next section of this chapter defines VHA mental health programs and services without making any statements regarding quality and service gaps; those topics will be addressed in later chapters. That section is followed by another section covering major VA mental health evaluation, research, and support centers that serve to monitor as well as inform clinical practice.

MENTAL HEALTH–RELATED PROGRAMS AND SERVICES

The VHA offers an array of recovery-oriented mental health programs and services for eligible veterans across the country, including programs for substance use disorders (SUDs). VHA mental health programs and services have been developed to create a comprehensive array of care from acute, intensive inpatient care to residential rehabilitation and a variety of outpatient services. Because a substantial percentage of veterans treated in any given program have comorbid mental health conditions, virtually all programs have either in-house services or services available by referral to address the complex combinations of issues presented by the veteran population. This section summarizes the key mental health programs and clinical services offered at VHA health care facilities.

Primary Care-Mental Health Integration

Primary care–mental health integration (PC-MHI) is based on the Institute of Medicine’s definition of primary care: Primary care is the provision of continuous, comprehensive, and coordinated care to populations undifferentiated by gender, disease, or organ system. It provides accessible, integrated, biopsychosocial health care services by clinicians who are accountable for addressing a large majority of personal health care needs, developing a sustained partnership with patients, and practicing in the context of family and community (IOM, 1996).

PC-MHI was widely implemented throughout the VHA health care system beginning in 2007 (Johnson-Lawrence et al., 2012) and must be available at all VA medical centers (VAMCs) and at all large and very large community-based outpatient clinics (VA, 2015c). Primary care providers identify and address mental health conditions at the “sub-clinical, minor, or moderate levels before they escalate to full diagnostic-level problems” (Dundon et al., 2011, p. 10). PC-MHI providers are members of patient-aligned care teams (PACTs); collaborate with other team members to assess, support, or provide treatment; and conduct follow-up care (VA, 2012a). The VHA began implementing PACTs in its primary care clinics in 2010 (Rosland et al., 2013). PACTs are based on the patient-centered medical home model of health care. Each team consists of a primary care provider, a registered nurse care manager, a clinical associate (a licensed practical nurse or medical assistant), an administrative clerk, the veteran, and the veteran’s family and caregivers (VA, 2016k). Other personnel, such as social workers, dietitians, pharmacists, mental health practitioners, physical therapists, and specialists, can be added to

the team as needed. Each team provides care for about 1,200 patients (Rosland et al., 2013). Mild to moderate mental health conditions are managed within the PACTs (Kearney et al., 2014). In general, only patients who have severe mental health conditions are referred to specialty mental health services. The goals of the PACTs are to improve patient access to care through more efficient scheduling of appointments (including same-day appointments), to conduct more appointments by phone and by shared medical appointments, to increase patient access to personal health data and providers via the Internet, to improve coordination of care through the use of case managers and regular team “huddles,” and to improve communication between the care teams and their patients by training staff in patient-centered communication (Rosland et al., 2013). Chapter 12 presents more information about PACTs and other evidence-based care delivery approaches that systematically coordinate care given by VHA primary care, mental health, and substance-use treatment providers to effectively treat patients with mental health conditions.

General Outpatient Mental Health Services

General mental health clinics at VAMCs provide outpatient mental health services to veterans who do not require more specialized programs. Veterans should receive an appointment within 30 days. They will be seen by psychiatrists, psychologists, or other behavioral health providers who conduct a comprehensive evaluation and provide treatment (for example, psychotherapy, medications, and social support services) (VA, 2014e).

The VHA has recently introduced the Behavioral Health Interdisciplinary Program (BHIP) within its general mental health clinics (VA, 2014e). This model of care assigns patients to interdisciplinary teams of providers and clerical staff who coordinate and deliver the patients’ general mental health care. The goals of using the BHIP teams include better integration of outpatient mental health care, improved access for patients, and improved coordination and continuity of care. Chapter 12 presents more information about BHIP and other evidence-based care delivery approaches that systematically coordinate care given by VHA primary care, mental health, and substance-use treatment providers to effectively treat patients with mental health conditions.

Mental Health and Domiciliary Residential Rehabilitation and Treatment Programs

Mental Health Residential Rehabilitation and Treatment Programs (MH RRTPs) and Domiciliary Residential Rehabilitation and Treatment Programs (DRRTPs) provide services for a variety of illnesses, problems, and needs relating to the mental health of veterans in a residential setting. Care can be provided in general programs or, when appropriate and available, specialized programs as described below. MH RRTPs/DRRTPs provide a level of bed care that is distinct from high-intensity inpatient psychiatric care in that the patients do not require bedside nursing care and are generally capable of self-care (VA, 2010a). Candidates for admission have severe and often multiple conditions but do not need acute inpatient psychiatric or medical care and are not at significant risk to themselves or to others (VA, 2010a). To be eligible, veterans must lack stable living arrangements which are necessary for their recovery. Brief overviews of the different programs are detailed below, but the clinical policies and practices are identical for all programs, as determined by the Department of Veterans Affairs Central Office (VACO) (VA, 2013).

Some programs may provide the care within the departments themselves (referred to as the all-inclusive residential model), or they may have veterans receive services through outpatient programs such as psychosocial rehabilitation and recovery center while keeping residence in the MH RRTPs/

DRRTPs (the supportive residential model) (VA, 2010a). In either case, the purpose of the residential component is to provide a structured environment to integrate rehabilitative gains from treatment into a lifestyle of self-care and personal accountability.

The VHA acknowledges that access to these programs can be difficult for the veterans who need them. The handbook outlining the MH RRTPs/DRRTPs policies cites veteran poverty, homelessness, disabilities, and psychological conditions as barriers to admission to MH RRTPs/DRRTPs. The handbook also cites transportation to screening appointments as another barrier to the programs. In response to these barriers, the VA requires that screening for admission occur during one single contact (VA, 2010a). Also, the MH RRTP/DRRTP program manager or the domiciliary chief is responsible for facilitating improved access to screening appointments by providing transportation assistance to veterans who may have difficulty getting to appointments.

Psychosocial Residential Rehabilitative Treatment Program and General Domiciliary

A Psychosocial Residential Rehabilitative Treatment Program (PRRTP) and a General Domiciliary (Gen Dom) provides a residential level of care to veterans who do not require a more specialized program. PRRTPs are typically more structured, “all inclusive” units serving veterans with serious mental illnesses, while Gen Dom beds within MH RRTPs/DRRTPs are generally less structured and serve veterans with less severe conditions (VA, 2010a). Veterans who need specialty care for a specific condition should not be admitted to the PRRTP or Gen Dom, but rather to a program that addresses the needed specialty care (VA, 2010a).

Health Maintenance Domiciliary

Health maintenance domiciliaries are MH RRTPs/DRRTPs that focus on symptom reduction and stabilization as part of the treatment approach to recovery and community reintegration (VA, 2010a). These programs target veterans with more complex medical problems comorbid with their psychiatric conditions than are typically found in other residential programs.

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder–Residential Rehabilitative Treatment Programs or Domiciliary Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Posttraumatic stress disorder–residential rehabilitative treatment programs (PTSD-RRTPs) and domiciliary posttraumatic stress disorder programs (Dom-PTSDs) provide care to veterans who have PTSD, including those who have suffered military sexual trauma (MST). PTSD-RRTPs and Dom-PTSDs provide PTSD treatment, SUD treatment, and psychosocial rehabilitation (employment, community supports, and housing) (VA, 2010a).

Substance Abuse Residential Rehabilitative Treatment Program and Domiciliary Substance Abuse

Substance abuse residential rehabilitative treatment programs (SARRTPs) and domiciliary substance abuse (Dom SA) programs provide a residential level of care to a veteran population with diagnosed SUD. The programs provide a stable substance-free supervised recovery environment for veterans with SUDs who require a structured setting while they are treated and working toward recovery. Addiction severity, comorbidities, and a higher risk of relapse in a less structured environment are all reasons

why a SARRTP may be more appropriate than treatment in an ambulatory setting (VA, 2010a). To be admitted to a SARRTP, veterans must either require no monitoring or be at risk for no more than mild withdrawal according to a standardized clinician-administered assessment (Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment of Alcohol Scale, Revised) (VA, 2010a).

Women Trauma Recovery Program

The Women Trauma Recovery Program offers continuing PTSD treatment, sobriety maintenance, and employment and housing support (VA, 2010c). Each Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) must have a residential program that meets the needs of the women veterans it serves. If the number of women veterans within the VISN does not meet the threshold for that VISN to provide a specific program, the VISN is required to use national or regional resources to meet the clinical needs of women veterans who seek services.

Compensated Work Therapy–Transitional Residence Program

The goal of compensated work therapy–transitional residences (CWT-TRs) is to effectively reintegrate veterans into their home communities by fostering greater independence, improving social status, reducing hospitalization, and enabling community work based on the veterans’ capabilities and desires (VA Office of Inspector General, 2011). CWT-TRs target a wide variety of veterans, including veterans with severe SUDs who frequently rely on institutional care, homeless veterans with mental disorders who under-use VA services, veterans with PTSD, and veterans with serious psychiatric disorders and concomitant vocational deficits (VA, 2010a).

Domiciliary Care for Homeless Veterans

Domiciliary care for homeless veterans (DCHV) provides time-limited residential treatment to homeless veterans with significant health and social–vocational deficits. The program provides access to medical, psychiatric, and SUD treatment as well as access to social and vocational programs (VA, 2010a). The goals of the program are to address conditions and barriers that contribute to homelessness, health status, and employment performance. DCHV also aims to reduce the overall reliance of homeless veterans on VHA inpatient services and to prepare veterans for and place them in a safe community environment. The program admits veterans who are homeless or at risk of becoming homeless and gives priority to veterans who have recently been discharged from the military (VA, 2010a).

Acute Inpatient Mental Health Services

Veterans in need of intensive crisis-oriented assessment and intervention for their mental illness or SUDs are admitted to inpatient mental health programs. The inpatient program may be located within a VAMC, which is most common, or a non-VHA community facility that has an agreement with the VHA (VA, 2015c). Veterans who have urgent and severe mental health conditions must be admitted to an inpatient unit without delay. Inpatient SUD-specific units are far less numerous than in years past as these services are now generally provided by SUD-experienced staff in inpatient general psychiatry, medical, and surgical units (VA, 2012b). Inpatient stays are typically short term, with veterans moving to other levels of care when clinically appropriate and safe to do so. All VHA emergency departments are required to have mental health providers on site or on call (VA, 2015c). VAMCs with emergency

departments have to be equipped to provide observations or evaluations for up to 23 hours when necessary, either in the emergency department or on inpatient units.

Select Population Programs

Housing and Urban Development-Veterans Affairs Supportive Housing

The HUD-VASH program was established to provide housing and clinical assistance to the neediest veterans and their immediate families. In partnership with the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), the VA provides case management and clinical services, while HUD provides permanent housing subsidies through its Housing Choice program. Working with an assigned case manager, veterans in the HUD-VASH program develop a house stabilization plan that includes both housing and treatment needs and recovery goals. To be eligible for the program, veterans must be eligible for VHA health care services and either lack a regular nighttime residence or have a primary residence that is a shelter, temporary housing facility, or a place not normally used as a regular sleeping accommodation (National Center on Homelessness Among Veterans, 2012). In addition to housing, the veteran will be offered needed primary care, mental health, and SUD services as well as employment and financial management assistance and training. Case management services continue as long as the veteran needs them; however, the subsidized housing can extend indefinitely after case management support has ended (National Center on Homelessness Among Veterans, 2012).

Health Care for Homeless Veterans

The Health Care for Homeless Veterans (HCHV) program serves as a gateway to VA services for eligible veterans who are homeless and in need of care. Services and functions of the HCHV include outreach to veterans, treatment, rehabilitative services, case management, and transitional housing assistance. Through the use of contracted residential services in different communities, the program engages otherwise hard-to-reach homeless veterans and connects them with needed mental health, primary care, and SUD services (VA, 2014f).

Grant Programs

The Grant and Per Diem (GPD) program is designed to fund new projects in the public or non-profit sector that will provide services for homeless veterans. Competitively awarded grants may be used to fund up to 65 percent of the acquisition, renovation, or construction costs for a building that will be used to supply supportive housing or support services for homeless veterans. Grant awardees may also request per diem funding to help offset the operational costs of the associated projects (VA, 2014a). All VAMCs with at least 100 homeless veterans in their primary service area must have a GPD or alternative residential care setting (VA, 2015c).

The Supportive Services for Veterans Families program gives grants to private non-profit organizations and community cooperatives to provide a variety of supportive services (for example, case management; assistance in obtaining VA and other public benefits; and providing temporary financial assistance for rent, utilities, and other expenses) for low-income veteran families (VA, 2017a). The goal of this program is to promote housing stability to homeless and at-risk veterans and their families.

Healthcare for Re-Entry Veterans

The Healthcare for Re-Entry Veterans (HCRV) program is intended to connect veterans recently released from federal or state prison to needed primary care, mental health, or SUD services. The program also provides outreach through a police training coordinator and justice outreach coordinator to local police enforcement and criminal justice systems to educate and advocate for mental health treatment as an alternative to incarceration when veterans with mental illness commit non-violent offenses (VA, 2015c). Each VISN must appoint a full-time HCRV specialist to lead the effort (VA, 2015c). VACO policy encourages the assignment of one specialist per state (VA, 2015c).

Services for Returning Veterans-Mental Health

Services for Returning Veterans-Mental Health (SeRV-MH) teams were first used in 2005 to identify and reach out to veterans returning from deployment in Iraq and Afghanistan, to provide them with information about stress-related disorders and coping mechanisms, and to assess their mental health needs. The goal of the program is to engage veterans for early detection and correction of problems relating to mental health (VA, 2010c). Most SeRV-MHs are associated with facility PTSD programs. There are no requirements for facilities to implement SeRV-MH; the only requirement is that they are able to assess and treat the mental health needs specific to OEF and OIF veterans (VA, 2010c).

Occupational Programs

Compensated work therapy (CWT) programs provide vocational training and employment opportunities to veterans with the ultimate goal of successfully reintegrating the veteran into their home communities. CWTs are required in every VAMC and must be made available to any veterans who have trouble obtaining or maintaining employment because of occupational challenges relating to their mental illness or physical illness co-occurring with their mental illness (VA, 2015c). A variety of specialized programs operate under the CWT umbrella. These include the Incentive Therapy program, the Sheltered Workshop program, the Transitional Work program, the Supported Employment program, and the Transitional Residence program (described in the Mental Health Residential Treatment Program section above).

Vet Centers

The Vet Center program offers services that specifically address the psychological and social sequelae of combat-related problems in former active-duty, National Guard, and Reserve service members (VA, 2010b). In addition to providing readjustment counseling, Vet Centers offer community education, outreach to special populations, brokering of services with community agencies, and the referral of veterans to other VA services (VA, 2010b).

Every Vet Center has a multidisciplinary staff with at least one licensed mental health professional. The program is designed to provide easy access to services, separate from the bureaucratic obstacles veterans often face navigating the VA system (VA, 2010d). Services are provided confidentially and do not appear on the veterans’ VHA health record (although Vet Centers do maintain their own patient-record system). There are about 300 Vet Centers in the United States and its territories and about 70 mobile Vet Centers which are used for outreach and to reach veterans who live in rural areas (VA, 2016l).

Services offered by Vet Centers include individual and group counseling for veterans and their families; family counseling for military-related issues; bereavement counseling for families who experience an active-duty death; counseling and referral for MST-related conditions; SUD assessment and referral; employment assessment and referral; Veterans Benefit Administration referral for benefit assistance; and medical and mental health screening and referral (VA, 2010d).

Chaplaincy

The VHA employs hospital chaplains and considers them to be a part of patient care teams (VA, 2015b). The chaplains’ role is to provide spiritual and pastoral care to veterans receiving treatment in all settings and levels of care, if desired by the veteran. Chaplain-provided care for veterans and service members who have mental health needs is a component of the VA/Department of Defense’s (DoD’s) Integrated Mental Health Strategy (DoD and VA, 2011). The VHA has a national Mental Health and Chaplaincy initiative that fosters the development of a more integrated system of health care (VA, 2016h). The reasons that veterans may seek mental health care from chaplains rather than mental health professionals include “reduced stigma, greater confidentiality, more flexible availability, and comfort with clergy as natural supports within a community” (Nieuwsma et al., 2013, p. 11).

Department of Veterans Affairs Crisis Line

The Veterans Crisis Line, which the VA administers jointly with the Department of Defense, was established in 2007 (originally called the National Veterans Suicide Prevention Hotline). The service, which can be accessed via a toll-free hotline, online chat (added in 2009), and text messaging (added in 2011), provides veterans and service members in crisis and their families and friends with immediate support and connects them with VHA mental health services. The responders are trained to address the mental health concerns of service members and veterans, and some responders are veterans themselves. Since 2007 about 2.9 million calls, 350,000 chats, and 73,000 texts have been received by the Crisis Line.1 Additional information on the Veterans Crisis Line can be found in Chapters 4 and 9.

PROGRAMS AND CENTERS SUPPORTING QUALITY OF MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES

This section summarizes the key VA centers and initiatives that support the VHA’s mental health clinical services. It does not describe the interaction of these entities with each other and with the clinical care systems, however, as that goes well beyond the scope of the present study. Nor does this section provide an exhaustive list of support centers; there are additional VA centers that include mental health as part of their portfolios.

Northeast Program Evaluation Center

The Northeast Program Evaluation Center, located in West Haven, Connecticut, is responsible for overseeing and evaluating the VHA’s mental health services’ programs, and it produces several products. It periodically releases “report cards” on the National Mental Health Program Performance Monitoring System, which are evaluation reports of the VHA’s mental health programs. Similarly,

___________________

1 Personal communication, VA, June 16, 2017.

it produces the Long Journey Home reports, which report on the status of the VHA’s specialized treatment programs for PTSD, the VHA’s PTSD specialists, and the SeRV-MH program (VA, 2010c, 2014b). The center produces toolkits for sites to use in creating reports for accreditation purposes and also produces PTSD fact sheets. It supports ad hoc data requests from the Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention and provides support to the PTSD Mentoring Program and other National Center for PTSD initiatives (Hoff, 2014).

Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Centers

Congress established the Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Centers (MIRECCs) program in 1996 to explore the causes of and treatments for mental health disorders. The centers are charged with disseminating new findings into clinical practice and are located in 10 VISNs (VA, 2016f). Each MIRECC has a different focus. For a complete list of MIRECCs and their focus, see Table 3-1.

In addition to conducting research on mental health conditions, the MIRECCs also work to implement the new findings in order to improve clinical practice in the VHA. For example, efforts to implement supported employment, an evidence-based treatment for schizophrenia, in four VISNs resulted in 2.3 times more veterans receiving this type of treatment (VA, 2015a). These centers also are funded to provide postdoctoral training in mental health for physicians in psychiatry, neurology, radiology, internal medicine, or other areas of medicine and for allied health professionals from clinical psychology, counseling psychology, social work, nursing, and pharmacy (VA, 2016g).

Centers of Excellence

Centers of excellence are designed to be incubators for new methods of treatment and service delivery (VA, 2011). Each center has a different focus. See Table 3-2 for a list of the centers, their locations, and their focuses.

| MIRECC | Focus |

|---|---|

| New England MIRECC | Improve services for veterans with dual diagnoses (that is, veterans with mental illness in combination with addiction problems) |

| VISN 2 MIRECC | Maximize recovery for veterans with SMI |

| VISN 4 MIRECC | Treatment and prevention of comorbid medical, mental health, and/or SUD |

| Capitol Health Care Network MIRECC | Improve the care of all veterans with schizophrenia and other SMI |

| Mid-Atlantic MIRECC | Clinical assessment and treatment of postdeployment mental illness and related problems, development of novel mental health interventions |

| South Central MIRECC | Improve access to evidence-based practices in rural and other underserved populations |

| Rocky Mountain Network MIRECC | Reduce suicide in the veteran population |

| Northwest MIRECC | Applies genetic, neurobiological and clinical trial methods to the discovery of effective treatments for major mental disorders |

| Sierra Pacific MIRECC | Improve clinical care for veterans with dementias and with PTSD |

| Desert Pacific MIRECC | Improve the outcome of patients with chronic psychotic mental disorders (schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and psychotic mood disorders) |

NOTE: MIRECC = Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; SMI = serious mental illness; SUD = substance use disorder; VHA = Veterans Health Administration; VISN = Veterans Integrated Service Network.

SOURCE: VA, 2016a.

TABLE 3-2 VA Centers of Excellence

| Center of Excellence | Location | Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Center for Integrated Health Care | Syracuse VA Medical Center; VA Western New York Health Care System at Buffalo | Improve the integration of mental health services into the primary care setting |

| Center of Excellence for Suicide Prevention | Canandaigua Medical Center, New York | Reduce the morbidity and mortality in the veteran population associated with suicide |

| Center of Excellence for Research on Returning War Veterans | Doris Miller VA Medical Center, Waco, Texas | Improve knowledge about mental health issues in returning war veterans, with a particular focus on OEF/OIF/OND veterans |

| Center of Excellence for Stress and Mental Health | VA San Diego Health Care System, California | Improve knowledge about the effects of stress and trauma-related health problems |

| Center of Excellence for Substance | Philadelphia VA Medical Center, | Provide advice to the VA Central |

| Abuse Treatment and Education | Pennsylvania; Puget Sound VA Health Care System, Washington | Office on how to improve SUD treatment; evaluate research on SUDs and treatments |

NOTE: OEF/OIF/OND = Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom/Operation New Dawn; SUD = substance use disorder; VA = Department of Veterans Affairs.

SOURCE: VA, 2011.

Quality Enhancement Research Initiative and Center for Mental Health and Outcomes Research

The Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) and the Center for Mental Health and Outcomes Research operate under the Health Services Research and Development Service within the VHA (VA, 2014c). QUERI’s mission is to enhance the quality and outcomes of VHA health care by systematically implementing clinical research findings and evidence-based recommendations into routine clinical practice (VA, 2014c). QUERI evaluates quality of care across three domains—structure, process, and outcomes—and is committed to using research results to drive improved interventions within the VHA health system. The QUERI program, first established in the 1990s, has recently evolved from 10 centers, each with a focus on a specific disease or condition, such as the Substance Use Disorder QUERI and the Mental Health QUERI, to a collection of 15 interdisciplinary programs with cross-cutting partnerships aimed at achieving VHA national priority goals and specific implementation strategies. For example, in the area of mental health, the QUERI for Team-Based Behavioral Health (in Little Rock, Arkansas) focuses on how team-based behavioral health care can be improved through the use of implementation facilitation strategies, with the ultimate goal of improving veteran outcomes. The Care Coordination QUERI (in Los Angeles, California) aims to learn how to improve coordination between the veteran, his or her primary care team, and any specialty care, emergency department, hospital, and home community resources the veteran may need (VA, 2017b). And the mission of the Center for Mental Health and Outcomes Research (located in North Little Rock, Arkansas) is “to optimize outcomes for veterans by conducting innovative research to improve access to and engagement in evidence-based mental health and substance use care” (VA, 2017c). In particular, its focus is to conduct research to improve mental health care for rural veterans.

Serious Mental Illness Research and Evaluation Center

The Serious Mental Illness Research and Evaluation Center (SMITREC) is a national center for data collection and management and focuses on veterans with serious mental illness. The center runs the National Psychosis Registry and the National Registry for Depression, which collect and maintain data from all VHA patients with these diagnoses (VA, 2014d). Offices within VACO as well as at the VISN and facility level can access these data in order to evaluate clinical practices and inform policy. SMITREC is located within the Ann Arbor VA Center for Clinical Management Research.

SMITREC’s mission is to conduct critical evaluation that will (1) enhance the mental and physical health care of veterans with serious mental illnesses by providing clinicians with state-of-the-art information on the effectiveness of treatment options; (2) inform the VA on issues of access to care, customer and clinician satisfaction, efficiency, and the delivery of quality health care; and (3) provide VA policy makers with relevant and timely guidance on key issues important to optimizing the system-wide delivery of health care to veterans with serious mental illness (VA, 2014d).

Program Evaluation and Resource Center

The VA’s Program Evaluation and Resource Center (PERC) provides program evaluation and technical assistance for mental health quality improvement efforts across the VHA (Trafton, 2014). Specific activities conducted by PERC include monitoring the organization and delivery of mental health and substance-use treatment services in primary and specialty care programs; improving the accessibility, processes, and outcomes of interventions for patients with mental health and SUDs; providing data, analyses, and technical assistance to facilitate the implementation of policies on mental health and substance use treatment; and conducting program evaluations, as requested. An example of an ongoing evaluation conducted by PERC is its quarterly review of more than 200 quality measures used to assess implementation of the Uniform Mental Health Services Handbook, access to care, use of evidence-based practices, and veterans’ health status. The center also conducts annual VHA provider and veteran satisfaction surveys, an annual assessment of health care diagnosis and treatment trends for VHA patients with SUDs, and monthly assessments of VHA mental health staffing levels, among other evaluations.

National Center for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

The National Center for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (NCPTSD), which was created in 1984, consists of seven divisions located at academic centers across the United States (Schnurr, 2014). Each division has a specific focus area (see Table 3-3).

The mission of the NCPTSD is to “advance the clinical care and social welfare of America’s veterans and others who have experienced trauma, or who suffer from PTSD, through research, education, and training in the science, diagnosis, and treatment of PTSD and stress-related disorders” (VA, 2016j). The center’s accomplishments include development of the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale, which is considered the gold standard for assessing PTSD; conducting the first VHA multisite study on PTSD; and creating a comprehensive website on trauma and PTSD (www.ptsd.va.gov). The NCPTSD has conducted several research projects on PTSD in veterans of OEF/OIF/OND. Examples include studies of neuropsychological and mental health outcomes following deployment (Vasterling et al., 2006), research on the effectiveness of specific treatments for PTSD (Brief et al., 2013; Lang et al., 2012), and work on predicting postdeployment mental health needs (Vogt et al., 2011).

TABLE 3-3 National Center for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Focus Areas by Division

| Division | Location | Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Executive Division | White River Junction, VT | Provides leadership, directs program planning, and promotes collaboration to facilitate the optimal functioning of each division individually and collectively. Specializes in the development of innovative and authoritative educational resources, programs that disseminate and implement best management and clinical practices, and the use of technologies to reach a broad range of audiences. |

| Behavioral Sciences Division | Boston, MA | Study of the role of behavior in adaptation to traumatic stress to advance knowledge of the mechanisms, course, assessment, and treatment of stress- and trauma-related psychopathology. |

| Clinical Neurosciences Division | West Haven, CT | Neurobiological, imaging, and genetic studies of the physical basis of traumatic stress, risk and resilience factors, and pharmacotherapy and rehabilitation for PTSD and comorbid conditions. |

| Women’s Health Sciences Division | Boston, MA | Assessment and treatment of the psychological and physical health impact of military service on women as well as of military sexual trauma in men and women. |

| Evaluation Division | West Haven, CT | Supports the National Center’s mission through a programmatic link with VHA’s Northeast Program Evaluation Center, which has broad responsibilities within the Office of Mental Health Operations to evaluate their programs, including those for specialized treatment of PTSD. |

| Dissemination and Training Division | Palo Alto, CA | Research on provider and patient needs and preferences, implementation and effectiveness of evidence-based assessments and treatments in community settings, and development and testing of novel assessments and treatments that exploit the potential unique benefits of technology-based delivery of services to improve access, quality and outcomes in VHA care. |

| Pacific Islands Division | Honolulu, HI | Improving access to care for active-duty personnel and veterans by improving understanding of cultural attitudes and the use of advanced technology, such as telemedicine, to reach out to veterans unable to access adequate care. |

NOTE: PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; VHA = Veterans Health Administration; VISN = Veterans Integrated Service Network.

SOURCES: Schnurr, 2014; VA, 2016d.

National Telemental Health Center

The VHA National Telemental Health Center, based in the VHA Connecticut Healthcare System, was created to unify the use of tele-mental health within the VHA. The center works to ensure that telemental health is available nationwide, and it strives to increase access to specialty care via telehealth. Furthermore, it convenes panels of experts to help advance the field and acts as a resource bank for best practices (Godleski, 2014). For PTSD treatment, the National Telemental Health Center is promoting the delivery of prolonged exposure therapy and cognitive processing therapy via tele-mental health, particularly to veterans in rural areas where these therapies may not be otherwise available (IOM, 2014).

National Center on Homelessness Among Veterans

The VA’s National Center on Homelessness among Veterans was established in 2009 and collaborates with the Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention to address homelessness among veterans. The center’s goal is “to promote recovery-oriented care for veterans who are homeless or at-risk for

homelessness by developing and disseminating evidence-based policies, programs, and best practices” (VA, 2016a). Between 2010 and 2015, efforts by the VA and its partners reduced the estimated number of homeless veterans by 36 percent. According to estimates based on data collected during the annual point-in-time count, conducted on a single night in January 2015, there were fewer than 48,000 homeless veterans in the United States, a decline of more than 26,360 veterans since 2010.2

The center conducts population-based and program-specific research on homelessness and also develops assessment tools. One particular area of this population-based research is mental illness, SUDs, and comorbid conditions (VA, 2016d). For example, VA researchers have studied housing disparities and instability among veterans who have mental illnesses, substance use and housing programs for homeless veterans, and unemployment among homeless veterans (Bossarte et al., 2013; Montgomery et al., 2015; O’Connor et al., 2013; Schinka et al., 2011). A study specific to the OEF/OIF/OND veterans is identifying risk factors for homelessness in this cohort (Metraux et al., 2013). Program-specific research is focusing on patterns of resource use and access to and provision of services as well as on identifying the factors that affect the outcomes of individual program initiatives on homelessness (VA, 2016e). Finally, tools are being developed so that the VA’s homelessness programs can be evaluated and the individual needs of veterans can be effectively assessed (VA, 2016b).

The center also has a program to develop and implement models related to housing, health care, prevention, and supportive services for homeless veterans (VA, 2016a). This program uses interventions developed from research studies and applies them to clinical practice. It also evaluates the efficacy of the interventions through pilot programs.

Finally, the center has an education and dissemination program that “provides education, technical assistance, and consultation to enhance and improve the delivery of services to homeless veterans by sharing evidence-based and best practices with VA and community partners” (VA, 2016c). This program develops treatment manuals and trainings and organizes virtual conferences and webinars to disseminate information.

Social and Community Reintegration Research

The Social and Community Reintegration Research (SoCRR) program is working to increase the VA’s capacity for conducting research on sustaining and recovering “full community involvement by veterans with psychiatric disorders” (VA, 2016i). SoCRR is funded by the VA’s Rehabilitation Research and Development Service under the Research Enhancement Award Program mechanism. The goal of the research program is to improve the understanding of how mental health conditions affect community involvement factors such as education, work, and family and social relationships. The goal is to apply the research findings to clinical practices to assist veterans with their reintegration in the community.

SUMMARY

This chapter has provided a summary of VA programs and services related to mental health care and of major mental health evaluation, research, and support centers that serve to monitor as well as inform clinical practice. The chapter is intended to be solely descriptive. Select programs and services are examined in more detail with regard to access and quality in later chapters. The salient points from this chapter are as follows:

___________________

2 Personal communication, Stacy Gavin, OMHSP/VA, June 2, 2016.

- The VHA offers an array of recovery-oriented mental health programs for eligible veterans across the country, including programs for SUDs.

- The VHA also provides support services not traditionally found in non-VHA mental health venues, such as services targeting homeless veterans, vocational rehabilitation, and transitional services from federal or state prison to VHA health care.

- Both general and specialty mental health services are offered with a particular emphasis on areas that address the needs of the veteran population (for example, posttraumatic stress disorder and military sexual trauma).

- With few exceptions (for example, the Services for Returning Veterans–Mental Health teams), VHA mental health services have been developed to address the needs of military veterans broadly. Mental health services for the Operation Enduring Freedom, Operation Iraqi Freedom, and Operation New Dawn veterans are, for the most part, delivered within the existing mental health system described here.

- VHA mental health services and programs have been developed to create a comprehensive continuum of care from acute, intensive inpatient care to residential rehabilitation and an array of outpatient services.

- In addition to being a direct provider of and payer for services, the VHA has a large infrastructure dedicated to supporting and evaluating its programs and services, to conducting research to improve mental health care for veterans, and to training future health care providers (which will be discussed further in another chapter).

- Not all programs and services created by the VHA and described in this chapter are available at all sites of VHA care.

- The types and number of mental health services available at a particular site are determined by such factors as the number of veterans served and their needs and the size and location of the site.

- The location of services and how those services are delivered (for example, direct care, tele-mental health, or contracts with non-VHA providers) are prescribed by written national policy.

- In response to the diverse needs of veterans, the range of site size and locations (for example, rural versus urban), and other locally determined factors, a large number of general and specialized mental health programs have been created and are implemented in accordance with local needs.

- As such, varying subsets of these programs may be available at a particular site.

- Regardless of whether a mental health program is described as general or specialized, a substantial percentage of veterans treated in a given program typically have comorbid mental health conditions. Therefore, virtually all programs have either in-house services or services available by referral to address the complex collection of issues presented by the veteran population.

REFERENCES

Bossarte, R. M., J. R. Blosnich, R. I. Piegari, L. L. Hill, and V. Kane. 2013. Housing instability and mental distress among U.S. veterans. American Journal of Public Health 103(Suppl 2):S213–S216.

Brief, D. J., A. Rubin, T. M. Keane, J. L. Enggasser, M. Roy, E. Helmuth, J. Hermos, M. Lachowicz, D. Rybin, and D. Rosenbloom. 2013. Web intervention for OEF/OIF veterans with problem drinking and PTSD symptoms: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 81(5):890–900.

DoD and VA (Department of Defense and Department of Veterans Affairs). 2011. DoD/VA integrated mental health strategy (IMHS). Washington, DC: Department of Defense and Department of Veterans Affairs.

Dundon, M., K. Dollar, M. Schohn, and L. J. Lantinga. 2011. Primary care-mental health integration co-located, collaborative care: An operations manual. Center for Integrated Care.

Godleski, L. 2014. Telemental health in VA: Laying the groundwork for opportunities to access to cognitive behaviorial therapy for pain, part 1. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs.

Hoff, R. 2014. NEPEC and PTSD program evaluation. In Presentation to the Committee to Evaluate the Department of Veterans Affairs Mental Health Services. New Haven, CT: VA NEPEC.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1996. Primary care: America’s health in a new era. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2014. Treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder in military and veteran populations: Final assessment. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Johnson-Lawrence, V., K. Zivin, B. R. Szymanski, P. N. Pfeiffer, and J. F. McCarthy. 2012. VA primary care-mental health integration: Patient characteristics and receipt of mental health services, 2008–2010. Psychiatric Services 63(11): 1137–1141.

Kearney, L. K., E. P. Post, A. S. Pomerantz, and A. M. Zeiss. 2014. Applying the interprofessional patient aligned care team in the Department of Veterans Affairs: Transforming primary care. American Psychologist 69(4):399–408.

Lang, A. J., P. P. Schnurr, S. Jain, R. Raman, R. Walser, E. Bolton, A. Chabot, and D. Benedek. 2012. Evaluating transdiagnostic treatment for distress and impairment in veterans: A multi-site randomized controlled trial of acceptance and commitment therapy. Contemporary Clinical Trials 33(1):116–123.

Metraux, S., L. X. Clegg, J. D. Daigh, D. P. Culhane, and V. Kane. 2013. Risk factors for becoming homeless among a cohort of veterans who served in the era of the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts. American Journal of Public Health 103(Suppl 2): S255–S261.

Montgomery, A. E., M. E. Dichter, A. M. Thomasson, C. B. Roberts, and T. Byrne. 2015. Disparities in housing status among veterans with general medical, cognitive, and behavioral health conditions. Psychiatric Services 66(3):317–320.

National Center on Homelessness Among Veterans. 2012. HUD–VASH resource guide for permanent housing and clinical care. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs.

Nieuwsma, J. A., J. E. Rhodes, G. L. Jackson, W. C. Cantrell, M. E. Lane, M. J. Bates, M. B. Dekraai, D. J. Bulling, K. Ethridge, K. D. Drescher, G. Fitchett, W. N. Tenhula, G. Milstein, R. M. Bray, and K. G. Meador. 2013. Chaplaincy and mental health in the Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy 19(1):3–21.

O’Connor, K., A. Kline, L. Sawh, S. Rodrigues, W. Fisher, V. Kane, J. Kuhn, M. Ellison, and D. Smelson. 2013. Unemployment and co-occurring disorders among homeless veterans. Journal of Dual Diagnosis 9(2):134–138.

Rosland, A. M., K. Nelson, H. Sun, E. D. Dolan, C. Maynard, C. Bryson, R. Stark, J. M. Shear, E. Kerr, S. D. Fihn, and G. Schectman. 2013. The patient-centered medical home in the Veterans Health Administration. American Journal of Managed Care 19(7):e263–e272.

Schinka, J. A., R. J. Casey, W. Kasprow, and R. A. Rosenheck. 2011. Requiring sobriety at program entry: Impact on outcomes in supported transitional housing for homeless veterans. Psychiatric Services 62(11):1325–1330.

Schnurr, P. P. 2014. The National Center for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Presented to the Committee to Evaluate the Department of Veterans Affairs Mental Health Services. Washington, DC: VA National Center for PTSD.

Trafton, J. 2014. Mental health evaluation activities of the VA Program Evaluation and Resource Center. Presented to the Committee to Evaluate the Department of Veterans Affairs Mental Health Services. Palo Alto, CA: Program Evaluation and Resource Center.

VA (Department of Veterans Affairs). 2010a. Mental health residential rehabilitation treatment program (MH RRTP). VHA Handbook 1162.02.

VA. 2010b. VHA directive 1500: Readjustment Conselling Service (RCS) Vet Center Program. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs.

VA. 2010c. VHA handbook 1160.03: Programs for veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Washington, DC: Veterans Health Administration.

VA. 2010d. VHA handbook 1500.01: Readjustment Counseling Service (RCS) Vet Center Program. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs.

VA. 2011. Specialized mental health centers of excellence fact sheet. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs.

VA. 2012a. Primary care–mental health integration (PC-MHI) functional tool. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs.

VA. 2012b. VHA programs for veterans with substance use disorders (SUD). VHA Handbook 1160.04.

VA. 2013. VHA handbook 1160.06: Inpatient mental health services. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs.

VA. 2014a. Grant and Per Diem program: FAQs. http://www.va.gov/homeless/gpd_faq.asp#FAQ3 (accessed November 7, 2014).

VA. 2014b. PTSD: National Center for PTSD. http://www.ptsd.va.gov/about/major-initiatives/divisions-research/evaluation_division_research.asp (accessed October 3, 2014).

VA. 2014c. QUERI—Using research evidence to improve practice. http://www.queri.research.va.gov/ (accessed October 3, 2014).

VA. 2014d. SMITREC. http://www.annarbor.hsrd.research.va.gov/smitrec.asp (accessed October 6, 2014).

VA. 2014e. VA mental health services: Public report. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs.

VA. 2014f. VHA handbook 1162.09: Health Care for Homeless Veterans (HCHV) program. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs.

VA. 2015a. MIRECC/COE mental health innovations newsletter. http://www.mirecc.va.gov/newsletter/current.asp (accessed January 8, 2016).

VA. 2015b. Patient care services: National Chaplain Center. www1.va.gov/chaplain (accessed April 24, 2015).

VA. 2015c. Uniform mental health services in VA medical centers and clinics. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs.

VA. 2016a. Homeless veterans. http://www.va.gov/HOMELESS/nchav/index.asp (accessed February 1, 2016).

VA. 2016b. Homeless veterans: Assessment tools. http://www.va.gov/homeless/nchav/research/assessment-tools/assessmenttools.asp (accessed Februaruy 2, 2016).

VA. 2016c. Homeless veterans: Education and dissemination. http://www.va.gov/homeless/nchav/education/education.asp (accessed February 2, 2016).

VA. 2016d. Homeless veterans: Mental illness, substance abuse, and co-occurring disorders. http://www.va.gov/homeless/nchav/research/population-based-research/mental-illness.asp (accessed February 1, 2016).

VA. 2016e. Homeless veterans: Program-specific research. http://www.va.gov/homeless/nchav/research/program-specific-research/program-specific-research.asp (accessed February 2, 2016).

VA. 2016f. MIRECC/COE. http://www.mirecc.va.gov/index.asp (accessed January 8, 2016).

VA. 2016g. MIRECC/COE VA advanced fellowship in mental illness research and treatment. https://www.mirecc.va.gov/mirecc_fellowship.asp (accessed August 31, 2016).

VA. 2016h. MIRECC/COE: Mental health and chaplaincy. http://www.mirecc.va.gov/MIRECC/mentalhealthandchaplaincy/index.asp (accessed February 11, 2016).

VA. 2016i. Office of Research and Development research programs. https://www.research.va.gov/programs/default.cfm#rrd-ct (accessed July 12, 2016).

VA. 2016j. PTSD: National Center for PTSD. http://www.ptsd.va.gov/about/divisions/index.asp (accessed January 13, 2016).

VA. 2016k. Team-based care—PACT. http://www.va.gov/HEALTH/services/primarycare/pact/team.asp (accessed January 28, 2016).

VA. 2016l. Vet Center Program. http://www.vetcenter.va.gov/ (accessed March 24, 2017).

VA. 2017a. Supporitive services for veteran families: General program information and regulations.https://www.va.gov/homeless/ssvf/index.asp?page=/home/general_program_info_regs (accessed October 6, 2017).

VA. 2017b. National network of QUERI programs. http://www.queri.research.va.gov/programs/default.cfm (accessed March 6, 2017).

VA. 2017c. COIN: Center for Mental Healthcare and Outcomes Research (CEMHOR), North Little Rock, Ar. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/centers/cemhor.cfm (accessed January 18, 2017).

VA Office of Inspector General. 2011. Healthcare inspection: A follow-up review of VHA mental health residential rehabilitation treatment programs (MH RRTP). Washington, DC.

Vasterling, J. J., S. P. Proctor, P. Amoroso, R. Kane, T. Heeren, and R. F. White. 2006. Neuropsychological outcomes of Army personnel following deployment to the Iraq war. JAMA 296(5):519–529.

Vogt, D., R. Vaughn, M. E. Glickman, M. Schultz, M. L. Drainoni, R. Elwy, and S. Eisen. 2011. Gender differences in combat-related stressors and their association with postdeployment mental health in a nationally representative sample of U.S. OEF/OIF veterans. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 120(4):797–806.

This page intentionally left blank.