5

Methodology

This chapter describes the mixed methodologic approaches that the committee used to assess Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF), Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF), and Operation New Dawn (OND) veterans’ access to the mental health services at the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) as well as the quality of those services. First, the full scope of efforts taken to plan the study and gather appropriate evidence is outlined. Next, the key methods used to carry out the information-gathering activities—developing and fielding a survey, conducting multiple site visits, and conducting a literature review—are described. Finally, the chapter concludes with some overarching limitations associated with the data collection and analyses.

APPROACH

The study was guided by a committee with expertise in epidemiology, health services research, internal medicine, mental health nursing, psychiatry, psychology, statistics, social work, survey research, and qualitative and mixed-methods research, among other important subject areas. As is the practice of National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine committees, this committee held public meetings for data-gathering purposes as well as closed meetings during which the committee deliberated about the evidence and about its conclusions and recommendations. This final report also underwent a blinded peer-review process prior to its publication.

The purpose of this study was to examine access to and the quality of the mental health care that the VA provides to OEF/OIF/OND veterans and to determine the extent to which veterans are afforded mental health treatment choices and offered a full range of necessary mental health services. To achieve this, the committee developed a mixed-methods approach, conducting both qualitative and quantitative original research (specifically, qualitative data collection from site visits and a survey of OEF/OIF/OND veterans). Prior to the original data collection and several times over the course of the study, the committee also completed a comprehensive literature review of existing research. In addition, the

committee reviewed results from VA-conducted surveys that assessed patient and provider satisfaction with VA mental health care services and heard presentations by experts from the VA and other organizations describing the VA health care system, how it is organized, and the types of benefits veterans are able to acquire.

The National Academies, in consultation with the committee, selected a subcontractor to conduct the survey and site visit tasks. The committee provided oversight to the subcontractor. Early in the study process the National Academies solicited proposals from potential subcontractors. The subcontractor chosen to assist the committee was Westat, a research corporation that consults in statistical design, qualitative and quantitative data collection and management, and research analysis work. Westat proposed a survey design that included a sampling plan, instrument development plan, a data collection plan, and a final analysis report based on the survey results. Westat also assisted with the development of qualitative interview protocols for site visits, planned and executed the site visits, and submitted individual site visit reports as well as a final qualitative analysis report1 across all sites.

The National Academies study began on September 30, 2013, and took 54 months to complete. The committee met 16 times over the course of the study to plan its approach to the charge; to develop the survey and site visit methods, instruments, and analysis plans in consultation with Westat; to obtain information from invited speakers and members of the public during four information-gathering sessions; to deliberate on the body of evidence from the survey, site visits, literature, and other sources of information; to draft its report; and to develop and come to consensus on the findings, conclusions, and recommendations.

To ensure that all research with human subjects was conducted in accordance with all federal, institutional, and ethical guidelines, all survey and site visit materials were approved by both the Westat and National Academies institutional review boards. The National Academies also acquired Paperwork Reduction Act clearance for the protocols from the Office of Management and Budget, which is required of all federally funded data collection projects to ensure they do not overburden the public with federally sponsored data collections. A certificate of confidentiality from the National Institutes of Health was also obtained, which further protects the privacy of study participants enrolled in sensitive, health-related research.

SURVEY METHODS

This section describes the quantitative research (survey) portion of the study. The committee conducted a survey of VA-eligible OEF/OIF/OND veterans, some who use VA health services and some who do not. Among those who are not using VA services (VA non-users), the survey assessed potential barriers to acquiring VA mental health care. VA-eligible OEF/OIF/OND veterans who are using mental health services were asked about their experiences with the VA and were used to support key analytic comparisons with the VA non-users.

The committee monitored and provided input on all phases of the survey work, including the sample and questionnaire designs, the data collection process, and the analyses of the data. Westat provided to the committee documentation during each phase, which the committee evaluated and as needed requested changes to the protocols and analyses. For the analytic phase, in addition to the summary tables of the data analyses, Westat provided to the committee the statistical analysis system (SAS) output and the

___________________

1 At the request of the VA, Westat also developed site-specific reports that were provided to the VA shortly after each site visit was completed to address any immediately actionable items that might pose a danger to staff and veterans if left unattended until the completion of this study. These reports were not a part of the committee’s work, but were provided to the committee.

constructed variables. The committee used this body of information to review and validate Westat’s analyses of the survey data. None of the information provided to the committee contained personally identifiable information.

Sample Design

Individuals eligible to participate in the survey were all U.S. civilians who served in the U.S. military during the time of OEF, OIF, or OND, from January 1, 2002, to December 31, 2014 (the war in Afghanistan began on October 7, 2001). In addition to including OEF/OIF/OND veterans who were deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan, the study population also included non-deployed veterans. The population eligible for the survey did not include those still on active duty, although it could include Reserve and National Guard members released from active duty, but still serving in those components. Table 5-3 shows that several cases separated or retired before January 1, 2002, or still on active duty were classified as ineligible.

A two-phase sample design was employed for the survey of OEF/OIF/OND veterans. Through a data use agreement, the VA provided the first-phase sample for the study, consisting of two data files. One file, containing 470,606 records, provided data for an approximate one-in-three sample of OEF/OIF/OND veterans who had served in-theater and, according to VA records, were alive on October 1, 2015. The data source for this file was the OEF/OIF/OND roster file. The second file, containing 724,738 records, provided data for a one-in-four sample of OEF/OIF/OND veterans who were not deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan in support of OEF/OIF/OND. The VA created this second file from multiple administrative data sources, and a veteran’s demographic variables were included only if the veteran appeared in VA medical records. In preparing the first-phase sample files, the VA removed duplicate records that may have appeared in the multiple sources used. As described in Appendix A, ensuring that the combined data sources for the first-phase sample fully covered the target population of interest involved comparing the associated population size to VA projections of the number of OEF/OIF/OND veterans alive on September 30, 2015 (using Veteran Population Projection Model 2014). These comparisons indicated the coverage of the first-phase sample was consistent with other information available from the VA about the numbers of OEF/OIF/OND veterans. These first-phase sample files contained an identifier with no personally identifiable information (a non-PII identifier) for each veteran in the first-phase sample, along with other non-PII variables (such as age, gender, military-service characteristics, and use of VA health care services). The variables available from the VA did not include a determination of honorable, less than honorable, or dishonorable.

This information was used by Westat to stratify the first-phase sample into 13 strata based on sex (where possible), deployment status, and use of VA mental health services. For the purposes of the sample, users of VA mental health services were defined as veterans who met one of the following conditions in the 24 months prior to the date the sample was drawn:

- An encounter at a mental health stop code;

- Two or more encounters at a primary care stop code with a mental health ICD-9 in any diagnostic position;

- Two or more encounters at an “other” stop code (for example, non-mental health or primary care) with a mental health ICD-9 in any diagnostic position; or

- Any inpatient encounter with a mental health ICD-9 in any diagnostic position.

TABLE 5-1 Second-Phase Stratification and Sample Sizes

| Sampling Stratum | Total Sample |

|---|---|

| Stratum 1 (not deployed; nonuser mental health services; sex unavailable; age unavailable) | 7,855 |

| Stratum 2 (not deployed; user mental health services; female; <30) | 145 |

| Stratum 3 (not deployed; user mental health services; female; 30+) | 510 |

| Stratum 4 (not deployed; user mental health services; male; <30) | 195 |

| Stratum 5 (not deployed; user mental health services; male; 30+) | 850 |

| Stratum 6 (deployed; non-user mental health services; female; <30) | 410 |

| Stratum 7 (deployed; non-user mental health services; female; 30+) | 1,535 |

| Stratum 8 (deployed; non-user mental health services; male; <30) | 970 |

| Stratum 9 (deployed; non-user mental health services; male; 30+) | 3,725 |

| Stratum 10 (deployed; user mental health services; female; <30) | 165 |

| Stratum 11 (deployed; user mental health services; female; 30+) | 545 |

| Stratum 12 (deployed; user mental health services; male; <30) | 605 |

| Stratum 13 (deployed; user mental health services; male; 30+) | 1,890 |

| Total | 19,400 |

The stratification allowed oversampling of female veterans, deployed veterans, and veterans who used VA mental health services. Stratification is often used in statistical surveys to improve the accuracy or precision of survey estimates by reducing sampling variance. On May 10, 2016, Westat selected a stratified second-phase sample of 19,400 veterans from the first-phase sample. The strata and corresponding sample sizes appear in Table 5-1. The total targeted sample size was 8,900 completed cases, which assumed a response rate of 46 percent across Web-based and computer-assisted telephone interview (CATI) data collection. That assumption led to the fielded sample size of 19,400.

The targeted response rate was estimated on the basis of recent VA surveys with similar methodology, including the Post-Deployment Afghanistan/Iraq Trauma Related Inventory of Traits Feasibility Study, the Survey of Veteran Enrollees’ Health and Use of Health Care, and the National Health Study for a New Generation of U.S. Veterans, and the a survey conducted by the Wounded Warrior Project. Two sections below, Final Survey Dispositions and Response Rate and Study Limitations, provide details about the final response rate for the committee’s survey.

Westat then provided the second-phase sample identifiers to the VA, which returned the identities and contact information for the veterans in the second-phase sample. Contact information included postal address, phone numbers, and Social Security numbers (SSNs). Once the SSNs were received back from the VA for the second-phase sample, a tracing file was created that was sent to Lexis Nexis to obtain updated phone numbers and postal addresses for use in data collection.

Appendix A contains the sampling and weighting plan, which provides additional details about the second-phase sample stratification variables and the stratum sample sizes and also contains additional details about the procedures used to weight the collected survey data and the results of a non-response bias analysis of resulting weighted estimates.

Questionnaire Design

The title of the survey was the OEF/OIF/OND Veterans’ Access to Health Services Survey. The survey content was drawn from several existing surveys administered to military and veteran populations and from existing validated scales. The sources of the committee’s survey items included the VA Survey of Healthcare Experiences of Patients Ambulatory Care, National Health Study for a New Generation of U.S. Veterans, National Survey of Veterans, National Comorbidity Study, Deployment

Risk and Resilience Inventory-2 (DRRI-2), Kessler-6, PTSD-PC (Primary Care PTSD screen), two-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2), Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), and Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST). For a complete list of sources the committee drew from to develop the survey questionnaire, see Appendix A.

The committee and Westat carefully reviewed those sources and selected the items that would appropriately address the study charge to examine unmet needs and barriers to receiving care among VA-eligible OEF/OIF/OND veterans, some who use VA health services and some who do not. As discussed in the sections that follow, the survey questionnaire includes a subset of questions asking the veteran about his or her mental health and well-being and about wartime experiences. These questions were necessary to determine the factors that underlie veterans’ mental health needs and their use of services.

Assessment of Warzone Stress Exposure

When the committee considered questions about warzone exposure for the survey, it determined that the available scales did not fit well into the survey it was developing. We felt that it was particularly important that the survey include a rigorous assessment of combat/warzone stress exposure because, whatever our findings would be on the need for and use of services and the differences in users and non-users of the VA, a predictable question would be whether and how these results might differ among those more or less exposed to war. Although various surveys conducted by the VA and the Department of Defense included a few individual items to assess specific stressors, none of these were developed using sophisticated psychometric analyses to develop indices or scales covering the full range of stressors highlighted in the literature. One instrument that was developed using psychometric methods and considered by the committee was the DRRI. It was developed by the National Center for PTSD (NCPTSD) by King et al. (2006), then updated to the DRRI-2, as a comprehensive measure of the various dimensions of warzone stress exposure specifically focused on those who served in OEF/OIF/OND (Vogt et al., 2013). However, this instrument was too long to be included in its entirety in the committee’s survey (17 scales with over 200 questions). So, at the committee’s request, staff at NCPTSD conducted an analysis of the DRRI-2 using the same data used on the development and validation of these measures. The intent of the analysis was to create a new, condensed scale of warzone stress exposure for the committee to include in its survey. NCPTSD completed stepwise regression to select a subset of questions from three DRRI-2 scales (Aftermath of Battle, Combat Experiences, and Perceived Threat). The subset was to account for at least 80 percent of the variance in the total scale and use approximately 25 percent (or less) of the total items from the selected scales. The committee reviewed NCPTSD’s results and chose a subset of questions to use for its study.

The results generated four options for the committee to consider. Among the options, the percent of variance accounted for by the items selected ranged between 90 and 96 percent. Upon reviewing the four options, the committee decided to use a scale composed of nine questions. The percent of variance in the total score accounted for by these nine questions was 96 percent, assuring us that our shortened scale corresponded very closely with the original DRRI-2 scale. In addition, the committee decided to have the lead-in question to those nine items ask the veteran respondent to consider all deployment experiences, not just the most recent one (a modification that had already been used successfully by others using the DRRI-2).

Summary of Survey Content

The survey is composed of eight sections, described below. The final survey questionnaire, including the sources of all screeners and questions used, can be found in Appendix A. Some sections are asked

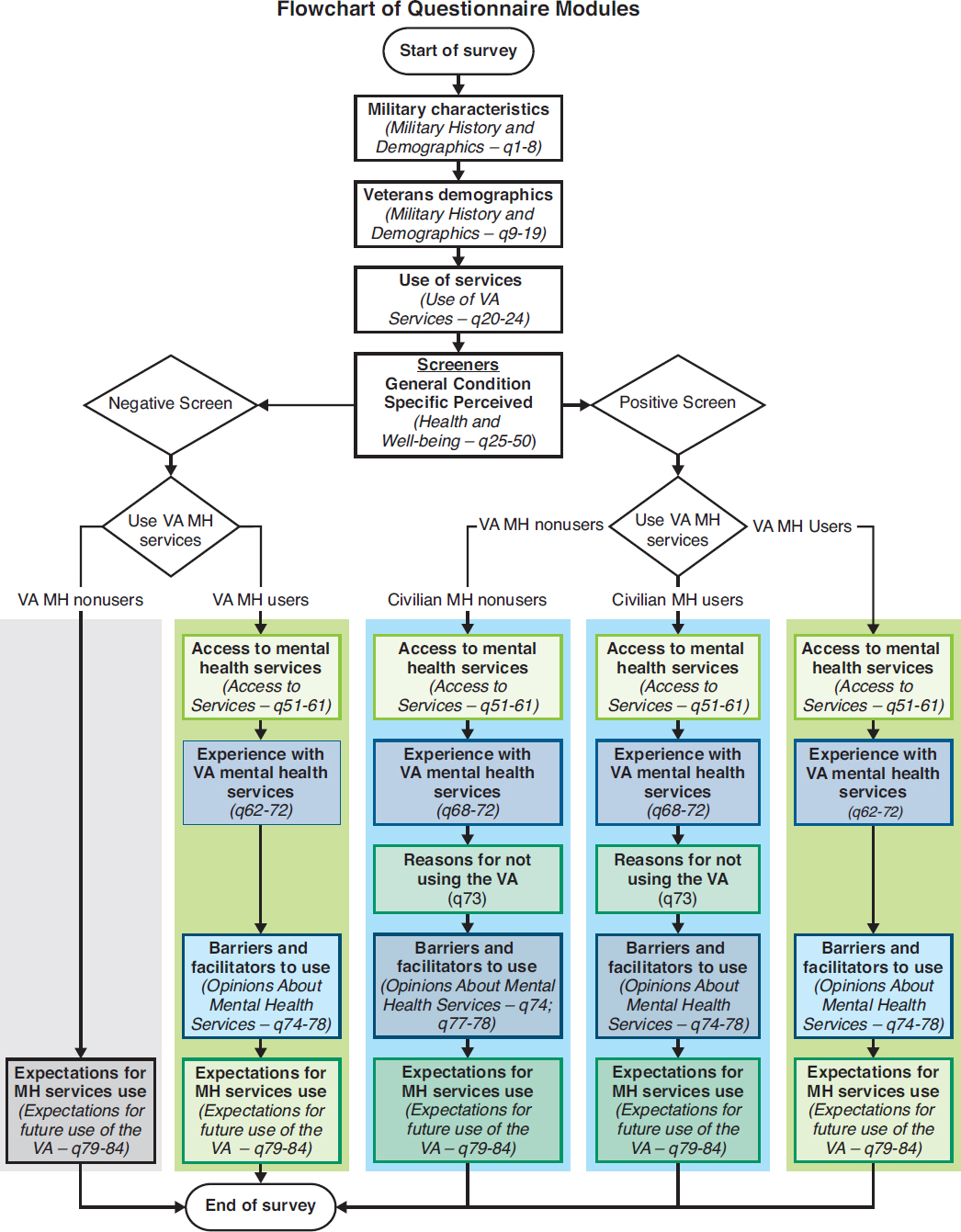

only of certain user groups (VA user, non-user, positive need, negative need). Figure 5-1 shows each section of the survey and every path a veteran would follow based on his or her answers to the Use of VA Services and Screeners sections (see Appendix A).

- Military History and Demographics. The questions in this section are asked of all veterans and cover basic military history, including the branches served in, the number of deployments, and experiences during deployments and also demographic information, including age, education, and employment status.

- Use of VA Services. The questions in this section are asked of all veterans and cover use of VA benefits and services. The responses to these questions determined whether a veteran would fall into the VA user or non-user group. Veterans who answered affirmatively to having used mental or behavioral health care through their VA primary care provider, a VA mental health treatment facility, or a Vet Center in the past 24 months, or if they indicated they used the VA for any mental or behavior health services (inpatient, outpatient, group therapy, psychotherapy, social skills training, or rehabilitation programs), were placed into the VA user group. An expanded discussion on need and user groups can be found later in the chapter.

-

Mental Health and Well-Being. The questions in this section are asked of all veterans. It contains the mental health screeners that suggest whether a veteran is in need of mental health services.2 The screeners included the scales listed below. The corresponding question number for each of the screeners in the questionnaire is given in parentheses. The full questionnaire can be found in Appendix A:

- Kessler-6 (to assess symptoms of nonspecific psychological distress) (Q26)

- A Kessler-6 score greater than or equal to 13 was considered positive

- PC-PTSD (to assess symptoms of PTSD) (Q27)

- A PC-PTSD score greater than or equal to 3 was considered positive

- PHQ-2 (to assess symptoms of depression) (Q28)

- A PHQ-2 score greater than or equal to 3 was considered positive

- AUDIT 10 (to assess symptoms of alcohol misuse) (Q29–Q38)

- An AUDIT 10 score greater than or equal to 16 was considered positive

- DAST (to assess symptoms of drug abuse) (Q39–Q48)

- A DAST score greater than or equal to 3 was considered positive

- Kessler-6 (to assess symptoms of nonspecific psychological distress) (Q26)

The questionnaire also included a question about the veteran’s perceived need for professional help (Q49), and questions asking whether the veteran has been told by a health professional in the past 24 months that he or she has PTSD, depression, alcohol dependence, drug dependence, any anxiety disorder, traumatic brain injury, or any other mental or behavioral health issue (Q50).

- Access to Services. The questions in this section are asked of veterans who use VA mental health services and veterans who screen positive for a mental health need.3

- Experience with VA Mental Health Services. The questions in this section are asked of veterans who use VA mental health services and veterans who screen positive for a mental health need,

___________________

2 These scales do not determine a condition; they assess the presence of symptoms that suggest the possibility of having a condition and the need for further assessment by a mental health professional to determine a diagnosis and whether there is a need for treatment.

3 Veterans who screened positive for a mental health need either screened positive on one or more mental health screeners, or reported receiving a diagnosis in the previous 24 months (or both).

-

though veterans who screen positive but do not use VA mental health services only received a portion of the section.

- Reasons for Not Using the VA. The questions in this section are asked of veterans who screen positive for a mental health need but do not use VA mental health care. This section consists only of an 11-item list of possible reasons for not using VA care for mental health issues.

- Opinions About Mental Health Services. The questions in this section are asked of veterans who use VA mental health services and veterans who screen positive for a mental health need.

- Expectations for Future Use of the VA. The questions in this section are asked of all veterans.

The questionnaire was pretested using cognitive interviews before the OEF/OIF/OND survey was administered in the field. Nine veterans participated in these interviews, which included filling out a paper version of the questionnaire and answering questions about their experience taking the survey. Veterans were asked how easy or hard the questions were to understand and answer, and about the clarity of instructions and terms used in the questionnaire. The pretest results were used to finalize the survey questions. A copy of the final survey instrument containing data annotations (for example, variable names and response values) can be found in Appendix A.

Data Collection Approach

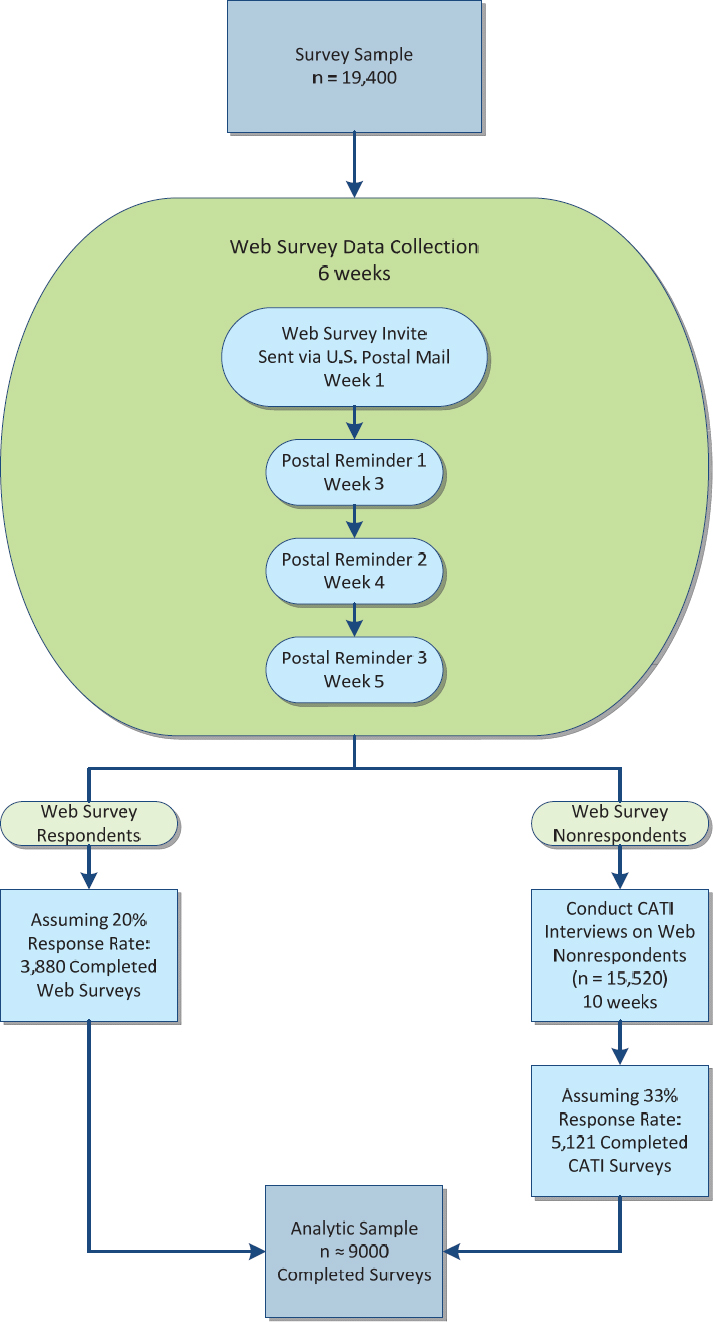

The multi-mode data collection approach included having the sampled veterans fill out a Web survey and following up non-respondents with telephone calls and having them complete a CATI. The sampled veterans were first contacted and invited to participate in the Web survey. The veterans were mailed an invitation letter that contained the Web survey URL and each veteran’s unique access code to the survey. Two weeks after the initial invitation mailing, non-respondents received the first of three weekly reminders via U.S. postal mail encouraging their participation in the survey.

Beginning in week 6 of the data collection field period, all non-respondents to the Web survey were moved to the telephone phase of the study. The CATI interviews were expected to be in the field for approximately 10 weeks in order for all veterans to be contacted a sufficient number of times. The original plan going into the data collection is shown in Figure 5-2 below.

The data collection schedule was initially planned as a 6-week Web survey phase to be followed by a 10-week CATI phase. After several weeks the Web survey returns indicated a lower than expected response rate. In an effort to improve the response, the schedule was revised to extend the Web data collection period for an additional 3 weeks for a total of 9 weeks before starting CATI. As a result, the CATI data collection began on August 25, 2016. It was planned to last 10 weeks and end on November 3, 2016, but during the CATI data collection period, a second decision extended the CATI field period an additional 3.5 weeks to end on November 27, 2016.

The data collection strategy included a progressive incentive scheme that would increase the incentive amount toward the end of the field period. The progressive incentive plan would allow us to target certain groups as required, based on differing response rates. In addition to a planned $2 pre-incentive, the initial data collection strategy included starting with a $5 promised incentive through the start of the CATI phase of data collection and increasing it to $20 during CATI.

TABLE 5-2 Timeline of Actual Data Collection Activities

| Activity | Date |

|---|---|

| Sample drawn | 5/10/16 |

| Web survey invitation letter mailed with $2 pre-incentive | 6/22/16 |

| Reminder letter #1 mailed | 7/6/16 |

| Reminder letter #2 mailed | 7/13/16 |

| Non-response calls conducted | 7/25/16–7/29/16 |

| Reminder letter #3 mailed | 7/27/16 |

| Interactive voice response (IVR) reminder calls conducted | 8/9/16–8/13/16 |

| CATI begins | 8/25/16 |

| Reminder letter #4 mailed to Stratum 1 | 10/14/16 |

| Reminder letter #4 mailed to remainder of Stratum 1 | 11/4/16 |

| Data collection ends | 11/27/16 |

Data Collection

Data collection for the OEF/OIF/OND Veterans’ Access to Health Services Survey began on June 22, 2016, when the invitation letter was mailed and ended on November 27, 2016, when the last CATI call was made. In total, 19,400 veterans were sampled and invited to participate in the study by completing either a Web survey or CATI interview. Table 5-2 presents a timeline of the major data collection milestones.

Final Survey Dispositions and Response Rate

Table 5-3 shows the final dispositions/result codes for all 19,400 sampled veterans at the completion of data collection. There were 3,061 Web surveys submitted as complete and 998 CATI interviews completed during data collection. Together, there were 4,059 surveys completed. Table 5-4 provides the final counts and percentages of sample cases by user and need status.

TABLE 5-3 Final Survey Status at End of Data Collection

| Result Code | Final Status |

|---|---|

| Web survey completes | 3,061 |

| CATI complete | 998 |

| Web survey started, not submitted | 181 |

| Deceased | 38 |

| Final Refusal | 13 |

| Incapacitated/Sick/Not available in field period | 5 |

| Ineligible – Not a veteran/Never in the Service | 15 |

| Ineligible – Separated/Retired before 1/1/2002 | 22 |

| Ineligible – Still on active duty | 16 |

| PND (Postal Non-Deliverable) | 2,744 |

| PND with new address | 62 |

| No response | 12,245 |

| Total Sample | 19,400 |

| Total Completes* | 4,059 |

| Return Rate | 20.9% |

*Web survey submits are included in the completes, although they may be determined later as not meeting a completeness rule.

TABLE 5-4 Final Survey Completes, by User and Need Status

| Analytic Group | Actual Number of Completes | Expected Number of Completes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | % | # | % | |

| User of VA MH Services | 832 | 20.5% | 2,200 | 24.7% |

| Need for Services (Positive Screen) | 788 | 19.4% | 2,000 | 22.5% |

| No Need for Services (Negative Screen) | 44 | 1.1% | 200 | 2.2% |

| Non-user of VA MH Services | 3,227 | 79.5% | 6,700 | 75.3% |

| Need for Services (Positive Screen) | 1,256 | 30.9% | 2,000 | 22.5% |

| No Need for Services (Negative Screen) | 1,971 | 48.6% | 4,700 | 52.8% |

| Total Number of Completed Surveys | 4,059 | – | 8,900 | – |

The final response rate for the survey, based on the American Association of Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) response rate definitions (specifically AAPOR RR2) is the number of completed interviews divided by the total number of eligible respondents. The eligible respondents are defined as the veterans in the sample file who are presumed to be alive. During the course of the data collection, it was learned that 38 sample members were deceased, and the number of deceased sample members was subtracted from the number of eligible sample members (denominator). Additionally, 53 veterans were determined to be ineligible during data collection and were also excluded from the eligible sample. Overall, the survey response rate was 22.0 percent, calculated as follows:

Response Rate = (number of completes + number of partial completes)/(number of total cases released – [number of deceased + number of ineligibles]) * 100

= [(4,059+181)/(19,400-(38+53)] * 100

= [4,240/(19,400-91)] * 100

= [4,240/19,309] * 100

= 22.0%4

The response rate is discussed in greater detail in the Study Limitations section later in this chapter.

Weighting

Analytic weights are needed for the production of statistically valid estimates and analyses of the survey responses. For the survey, a three-component weight was generated that reflected

- The selection probabilities of the sampled veterans by sampling stratum, called base weights;

- A non-response adjustment to account for the differential non-response that was observed across strata and demographic and other characteristics of veterans; and

- A final post-stratification adjustment to align the weighted totals from the sample to known distributions based on tabulations provided by the VA.

Base Weights

The base weight for a sampled veteran is simply the reciprocal of the probability of being selected into the sample. The base weight in this survey incorporated the two-phase sample design as discussed

___________________

4 Of the 181 partial completes, 121 were ultimately considered complete cases (according the committee’s criteria). Thus, 4,180 complete cases (4,059 + 121) were used in the final analysis.

earlier in this chapter. For the first phase of sampling, deployed veterans were selected at approximately a 1 in 3 rate, while non-deployed veterans were selected at approximately a 1 in 4 rate.

In the second phase of sampling, veterans were selected independently and at different rates within each of 13 strata formed as follows: First, non-deployed, non-users of VA mental health services formed one stratum. Second, deployed non-users of VA mental health services were stratified into four strata by cross-classifying their sex (2 levels: male or female) and age category (2 levels: <30, 30+). Finally, users of VA mental health services were stratified into eight strata by cross-classifying their deployment status (2 levels: yes or no), sex, and age category.

For purposes of increasing the precision of subpopulation estimates, female veterans, deployed veterans, and veterans who use VA mental health services were oversampled. Also, veterans younger than 30 were oversampled because it was expected that their response rate would be lower than that of older veterans.

The overall base weight of a given veteran was simply the product of the first-phase and second-phase base weights.

Non-Response Adjustment

A non-response adjustment was used to address the differing participation rates of different subgroups of veterans, some of whom were more likely to participate than others. The adjustment was developed to reduce the non-response bias of the survey estimates. A non-response analysis was conducted to identify the groups of veterans that exhibited different and disparate patterns of survey participation. An analysis called chi-square automatic interaction detector (CHAID) (Kass, 1980) was used to identify how veteran characteristics could be assembled to best explain the variation in survey participation. CHAID was used to identify 24 all-inclusive and mutually exclusive subgroups called “weighting cells” within which nonresponse weight adjustments were developed and applied to the constituent veterans. See Appendix A for more details.

The non-response adjustment calculation itself was straightforward. Within each weighting cell, the adjustment is the reciprocal of the weighted response rate of that cell using the base weights for the calculations. The magnitudes of the adjustment factor ranged from 2.32 to 6.19. The adjusted weights were calculated by multiplying the overall base weights of the survey respondents by the adjustment factor and by setting the adjusted weight of the non-respondents to zero.

Post-Stratification Adjustment

The final component of the analytic survey weight is a post-stratification adjustment. This adjustment aligns the weights of the sample respondents with known population distributions of veterans. Post-stratification can increase the statistical precision of survey estimates. An iterative proportional fitting method called “raking” (Kalton, 1983) was used to align the weighted sample of survey respondents—weighted by the base weight and non-response adjustment—to tabulations of veteran characteristics from the VA’s OEF/OIF/OND registry. Raking allows more distinct factors to be incorporated into the weighting adjustment process than otherwise would be achievable. Five raking cells were used that reflected a specific combination of sex, deployment status, and usage of VA mental health services during the previous 24 months. The raking cells were the four interior cells of Table 5-5 for deployed veterans plus a fifth cell that represented all non-deployed veterans. The raking factors ranged from 0.92 to 1.12. The final analytic weight for a “respondent” was its adjusted base weight multiplied by the combined non-response raking factor associated with the raking cell to which it had been assigned. The final analytic weight therefore incorporates three components—a base weight, a non-response adjustment, and a post-stratification adjustment. See Appendix A for more details.

| Raking Cells | Deployed Veterans | Non-Deployed Veterans | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male* | Female | ||

| Used mental health services in the last 24 months | x | x | |

| Did not use mental health services in the last 24 months | x | x | x |

*Includes unknown/missing.

Defining the Need and User Groups

The analysis dichotomized all survey respondents into two need groups—those with a mental health need and those without a mental health need. A respondent was designated as having a mental health need if he or she either screened positive on at least one of the mental health screeners (described in the Questionnaire Design section above) (Q26–Q48) or reported receiving a mental health diagnosis from a health care professional in the previous 24 months (Q50).5

Based on their reported mental health service use, respondents were classified into user groups based on how they responded to survey questions about where—if at all—they had sought mental health services in the previous 24 months (Q22 and Q23). Users were classified as either VA users or non-VA users. VA users indicated that they had received mental health care from VA primary care, VA mental health specialty care, Vet Centers, or any combination of the above in the past 24 months (Q22); or else they indicated that they had used the VA for mental or behavioral health services (inpatient, outpatient, group therapy, psychotherapy, social skills training, or rehabilitation programs) in the previous 24 months (Q23). Respondents who indicated that they received mental health care only through non-VA providers (either paid for or not paid for by the VA) in the previous 24 months (Q22) were classified as non-VA users. Respondents who indicated that they had not used any mental health care services at the VA or elsewhere in the past 24 months were considered non-users for the purposes of this study.

SITE VISIT METHODS

Below, the methodology for the qualitative research (site visit) portion of the study is described. Multiple interviews were conducted in each of the VA’s geographically divided networks, or Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VisNs), to obtain information from many interested parties, including VA staff (administrators and providers), staff at community-based organizations serving veterans, caregivers, and the veterans themselves—including those using and not using VA mental health services. The purpose of the interviews was to learn about the veterans’ experiences and any barriers or issues with access or quality that they encountered when using VA mental health services. At the time of this study there were 21 VISNs.6

___________________

5 It is possible that this definition generated a slight overestimate as it is plausible that some individuals who reported a diagnosis in the previous 24 months, but did not screen positive on any of the screeners, were not symptomatic at the time of the survey.

6 The VISN were undergoing reorganization during the study period. The reorganization process is expected to be completed in 2018. Therefore, the VISN geographic coverage and numbers in this report may not correspond directly to the current VISN geographic coverage and numbers.

Site Visit Objective

The objective of the site visits was to identify the range of experiences surrounding OEF/OIF/OND veterans’ access to VA mental health care services and the quality of those services. The site visits provided insights into how service providers and veterans themselves view both successes and problems with access to and the quality of VA mental health care services. The committee primarily used the site visit information to support and illustrate information from the committee’s survey and from the literature. In a few cases, when no information was generated in the survey or was found in the literature but was generated from the site visits, the committee presents the site visit information exclusively. The committee was mindful that due to the nature of qualitative research, it is not appropriate to generalize information gathered from a small population sample to the broader veteran population.

Data Collection Protocols

Before conducting the site visits the committee and Westat staff developed standardized data collection instruments. The general areas of inquiry were access to and barriers to VA mental health care services, the quality of the services, and the availability of treatment choices. Interviewees were asked for their suggestions for how the VA could improve its mental health care services. The instruments included semi-structured interview guides for each type of respondent (that is, VA staff, community providers, and veterans who use and do not use VA mental health services), a template for recording on-site observations, and a self-assessment form used for background information to be completed at each site by a local VA staff member designated by the VA medical center (VAMC) director. With respondents’ permission—and where feasible—all the data collected (from focus groups and in-depth interviews) were audio recorded, and the audio files were sent out for transcription. In instances where audio recording was not feasible (for example, ad hoc interviews, data collections conducted in loud environments such as restaurants, or when a participant asked not to be recorded or where no permission was given for recording), team members took notes. In addition, the research team developed a sheet of frequently asked questions (FAQs) to be handed out to interviewees during the site visits. Final versions of each site visit data collection instrument can be found in Appendix B of this report. A summary of the data collection modalities can be found in Table 5-6.

Staff Training

Westat’s field staff received project-specific training on site visit research procedures and data collection protocols. An initial, half-day training was held at Westat’s office in February 2015 and focused on two critical aspects of the study. First, the team reviewed the organization of service delivery within the VA, the geographic coverage provided by the VAMCs and their associated community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs), and the mental health service offerings required of these different types of facilities. Second, the team reviewed the process of conducting an “environmental scan”—a comprehensive review of services available to OEF/OIF/OND veterans in the geographic area served by the target VAMC—which was one of the steps in ensuring the success of each site visit. Together, the staff worked through a practice scan using the protocol and reviewed the contact sheet to be completed for each site visit.

A second, full day of training took place at Westat’s office in March 2015, which was also attended by the National Academies project staff. The goal of this training was to review the data collection procedures. This training included a discussion of the procedures for scheduling interviews, a review of all interview guides and other data collection protocols, data collection procedures, and a review of the National Academies’ site visit report template developed by the committee. In addition, the staff reviewed and discussed the protocol to follow in the event an interview participant became distressed.

TABLE 5-6 Site Visit Data Collection Modality and Location by Respondent Type

| Respondent Type | Data Collection Methoda | Location of Data Collection | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-Depth Interview | Focus Group | Self-Assessment Questionnaire | Environmental Scan Observation | At VA Facility | Off-Site | |

| VAMC Leadership/Administrators | X | X | X | X | ||

| VAMC Behavioral Health Leadership | X | X | ||||

| VAMC Behavioral Health Line Staffb | X | X | ||||

| VAMC OEF/OIF/OND Transition Team | X | X | ||||

| CBOC Behavioral Health Staff | X | X | X | |||

| Vet Center Staff | X | X | X | |||

| Community Mental Health Providers Veterans: | X | X | X | |||

| Currently Using VA Mental Health Services | X | X | X | X | ||

| Veterans: | ||||||

| Not Currently Using VA Mental Health Services | X | X | X | |||

| Site Visit Field Staff | X | X | X | |||

NOTES: CBOC = community-based outpatient clinic; OEF/OIF/OND = Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom/Operation New Dawn; VAMC = VA medical center; VA = Department of Veterans Affairs.

aData collection methods are a comprehensive snapshot across all sites.

bIncludes primary care–mental health integration (PC-MHI) team members, women’s clinic staff, PTSD clinic staff, directors of telehealth services, and peer support staff, among others.

The discussion included how to distinguish momentary distress from a psychiatric crisis, what steps to take to ensure the immediate safety of interview participants and staff, and the reporting requirements in the event of a psychiatric emergency. Westat staff assignments were made for each of the 21 sites, and provisional travel dates were established.

National Academies committee members and staff and Westat staff who attended the site visits were required to complete the VA’s Privacy and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act Focused Training and Privacy and Information Security Awareness and Rules of Behavior courses as well as Westat’s Human Subjects Protection Training course.

Site Selection

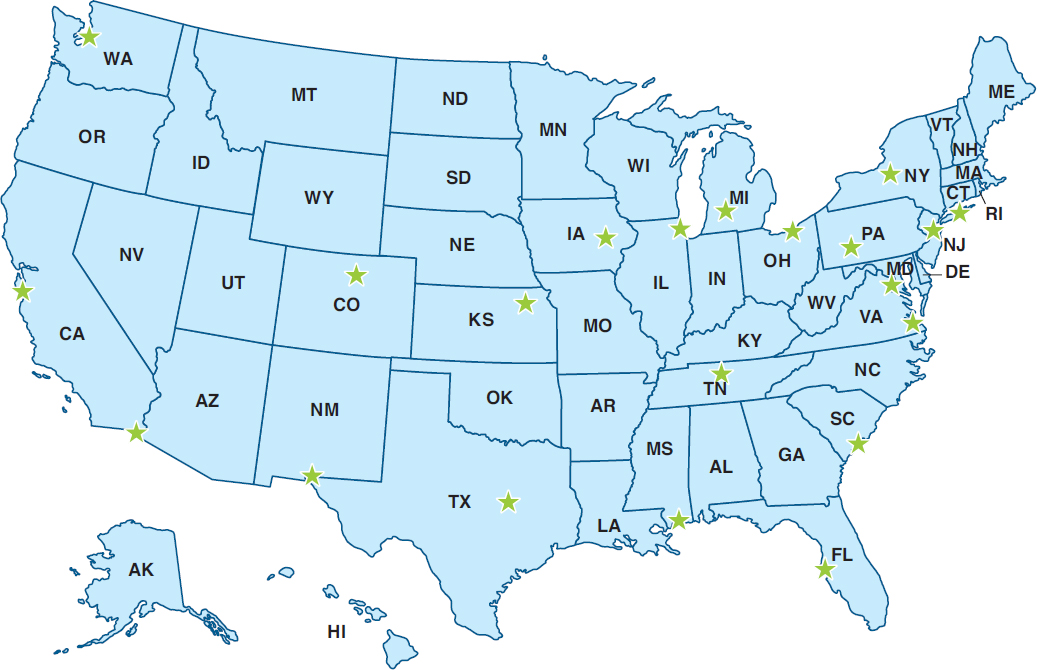

The principal goal of the site selection was to capture the heterogeneity of mental health care experiences from the perspectives of VA staff, local communities, caregivers, and, most importantly, from the OEF/OIF/OND veterans themselves. To this end, the site-selection criteria included the number of OEF/OIF/OND veterans served by each VAMC and its associated CBOCs; the geographic location of the site (for example, rural or urban); the demographic characteristics of the location (for example, locations with substantial minority populations); and, in some instances, the unique characteristics of the VAMC (for example, strong research participation, VAMCs affiliated with universities, and having a polytrauma clinic on site) that might offer insights into promising mental health treatment approaches for this cohort of veterans. Table 5-7 lists the sites that were subjectively selected by the committee and the dates when site visits were conducted. Figure 5-3 shows a map of the site visit locations.

TABLE 5-7 Sites and Dates of Site Visits (in Order by VISN Number)

| VISN # | Site/VAMC Name | Site Visit Dates (2015) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | VA Connecticut Health Care System West Haven, CT |

July 26–30 |

| 2 | Syracuse VA Medical Center Syracuse, NY |

July 19–23 |

| 3 | New Jersey Health Care Center East Orange, NJ |

Nov 16–20 |

| 4 | Altoona VA Medical Center Altoona, PA |

May 10–14 |

| 5 | Washington, DC VA Medical Center Washington, DC |

June 15–19 |

| 6 | Hampton VA Medical Center Hampton, VA |

Nov 2–5 |

| 7 | Ralph H. Johnson VA Medical Center Charleston, SC |

May 3–7 |

| 8 | James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital & Clinics Tampa, FL |

March 16–19 |

| 9 | Tennessee Valley VA Healthcare System Nashville, TN |

March 30–April 3 |

| 10 | Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center Cleveland, OH |

June 21–26 |

| 11 | Battle Creek VA Medical Center Battle Creek, MI |

July 19–24 |

| 12 | Jesse Brown VA Medical Center Chicago, IL |

October 12–16 |

| 15 | VA Eastern Kansas Health Care System Topeka, KS |

September 13–17 |

| 16 | Gulf Coast Veterans Health Care System Biloxi, MS |

September 20–24 |

| 17 | Olin E. Teague Veterans’ Medical Center Temple, TX |

November 2–6 |

| 18 | El Paso VA Health Care System El Paso, TX |

March 16–19 |

| 19 | VA Eastern Colorado Health Care System Denver, CO |

July 26–31 |

| 20 | VA Puget Sound Health Care System Seattle, WA |

June 21–26 |

| 21 | VA Palo Alto Health Care System Palo Alto, CA |

June 15–20 |

| 22 | VA San Diego Healthcare System San Diego, CA |

March 23–28 |

| 23 | Iowa City VA Health Care System (pilot site visit) Iowa City, IA |

February 9–13 |

NOTE: VA = Department of Veterans Affairs; VAMC = VA medical center; VISN = Veterans Integrated Service Network.

Site Visit Planning

Planning each site visit consisted of two major activities. First, Westat staff worked with site-specific points of contact to schedule the first day of interviews at the VAMC. Each visit began with a briefing of medical center leadership, followed by (in no set order) focus groups with the behavioral health

leadership team, with the behavioral health line staff, with the OEF/OIF/OND transition team, and with veterans who were currently using VA mental health services. Additional interviews, arranged as time allowed, included discussions with the primary care–mental health integration team members, women’s clinic staff, PTSD clinic staff, directors of telehealth services, and peer support staff, among others.

The next planning activity was the environmental scan, a comprehensive review of services available to OEF/OIF/OND veterans in the geographic area served by the target VAMC. Each scan sought to gain an understanding of the full range of VA-related services in the area (for example, CBOCs and Vet Centers) and of community-based organizations that might be working with large numbers of this cohort of veterans. Such organizations included 2- and 4-year colleges and universities, technical colleges, veterans service organizations (for example, VFW and Team Red, White, and Blue), and grassroots peer-support networks. They also included providers of mental health, wellness, and other services, including community mental health providers, organizations committed to health and wellness activities (for example, mindfulness training, yoga, sports and recreational activities), and veterans’ interest groups (for example, Combat Veterans Motorcycle Association chapters).

Site visit team members reached out to these organizations’ leaders to learn if the services being offered were germane to the study and, if so, to see if the team could interview both staff and OEF/OIF/OND veterans and their caregivers during the site visit. Through these activities, the teams ultimately developed site visit schedules that ensured a broad representation of service providers (for example, VAMC, CBOC, Vet Center, and community-based) and included the voices of as many veterans as pos-

sible. The schedules also included open times during which team members could follow up on information obtained while on-site and conduct ad hoc interviews. As an added level of oversight, members of the committee and National Academies staff participated in some of the site visits, although Westat staff conducted the interviews.

For each of the 21 selected sites, National Academies’ staff sent the director of the VAMC a letter informing him or her of the purpose, details, and timing of the site visit and requesting that a point of contact be assigned to help the site visit team coordinate and schedule staff interviews at the VAMC. Accompanying the letter was an optional self-assessment form that was to be completed by the director’s designee and returned to the site visit team 1 week prior to the start of the visit. Nineteen self-assessment forms were completed and returned. Because Vet Centers operate under a separate administrative structure, a similar letter (but not the self-assessment form) was sent to the readjustment counseling services regional director in advance of each visit.

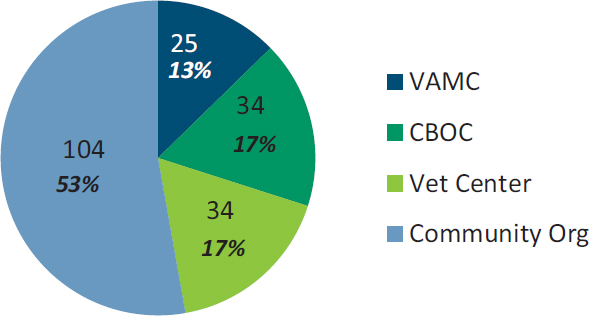

Data Collection

Across the 21 site visits, approximately 336 in-person, on-site, one-on-one interviews and focus groups at nearly 200 different locations (see Figure 5-4) were conducted.7 In each location staff began the site visit at the VAMC and spent the entire first day conducting interviews or focus groups with facility administrators, clinical staff, and veterans.8 Visits to local CBOCs generally involved interviews only with clinic staff, although in a few instances the staff had arranged for a small number of veterans to meet with the site visit team. The largest number of veteran interviews and focus groups was conducted at Vet Centers and community-based organizations. These organizations played a critical role in ensuring that the study included the voices of veterans, sometimes recruiting several groups of veterans, including those who were not using VA mental health services. This method resulted in a convenience sample comprising people who volunteered to speak with the interviewers and who were available during the time of the visit. The sample is not representative of the larger OEF/OIF/OND veteran population.

___________________

7 This number is based on the number of interview transcripts and typed notes that the analysis team reviewed for this report. This number does not include ad hoc interviews that were not audio recorded and notes or information garnered from calls made for the environmental scans.

8 Several locations had more than one VAMC. In four of these sites, staff at the second VAMC were included in the first-day interviews by video or telephone conference, or team members interviewed these staff separately on a different day of the visit.

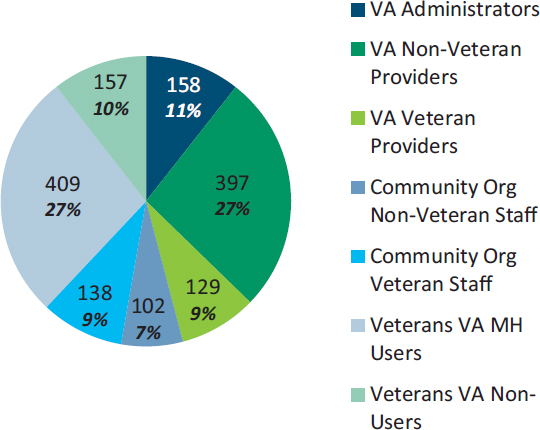

Figure 5-5 provides details about the numbers and types of interviewees. Of the nearly 1,500 study participants, just under half (684) were employed at either a VAMC or CBOC. Among the more than 500 VA providers interviewed, about one-quarter self-identified as military veterans. Teams also interviewed 240 individuals working with community-based service providers or organizations, including private-sector mental health providers; staff leading student veterans associations on college campuses; staff working in organizations dedicated to veteran social, emotional, and physical wellness; and Vet Center staff.9 Overall, nearly 60 percent of these participants said they were veterans.

The team also gathered information from more than 550 non-provider OEF/OIF/OND veterans10 and a small number of veterans from other eras11 about their experiences with and views on VA mental health services (the participants were identified through the environmental scan). When veterans from other eras participated, it was often in instances where the VA staff or other points of contact identified them as the only volunteers who were willing to be interviewed or when they were part of a therapy group that integrated veterans from more than one era and the group as a whole agreed to participate.

Field staff observed that approximately 40 percent of veteran participants were racial or ethnic minorities, and just under 20 percent were women. Figure 5-6 shows the branch of service for the ap-

___________________

9 Vet Centers receive their funding from the Department of Veterans Affairs but do not share patient records with the VA unless they have explicit permission from the patient. Vet Centers provide free counseling services to all combat veterans, including many who are not eligible for VA services. For example, Vet Center counselors can provide services to active-duty service members.

10 Caregivers have been included in the total for veterans interviewed by the site visit teams. In some cases, the caregiver (almost always a spouse) accompanied the veteran; in others, data collection was conducted with just the caregiver. In the 13 site visits where caregivers were counted separately from veterans (that is, the category was not OEF/OIF/OND Veterans or Caregivers–VA Service Users/Non-Users), they totaled only 12. Thus, the vast majority of “veteran participants” were, indeed, the veterans themselves.

11 All study materials and requests for veteran participants specified that the study was focused on the cohort of OEF/OIF/OND veterans. However, in some cases, veterans from other eras participated in the discussions. Their numbers are not included in any of the participant totals.

proximately 350 veterans who reported this information during audio-recorded interviews; the majority were from the Army. Approximately three-quarters of the veteran participants reported that they were either currently receiving mental health services through the VA or had done so at sometime within the past 2 years. The remaining veterans were classified by study team members as non-users of VA mental health services; that is, they either had never accessed VA mental health services, or had done so but not within the past 24 months (although they may have been accessing counseling services through the Vet Centers). Individuals so categorized included

- Veterans who had TRICARE or commercial health insurance through their employers and were using services in the private sector;

- Veterans who did not perceive themselves as having a need for any mental health services, regardless of the service location;

- Veterans who did have a perceived need for mental health services, but were reluctant to seek assistance through the VA; and

- Veterans who had previously received services at the VA, but who had stopped using those services.

After reviewing a few of the early site visits, the committee suggested that the site visit team attempt to increase representation of the non-users in the study by reaching out to locations serving extremely low-income veterans, such as food banks and homeless shelters. However, veterans served in these locations appear to be well connected with the VA for two important reasons. First, these individuals often have no other health insurance, and if they are not using the VA for care, they are consuming county or state resources for indigent populations. It is thus in the locality’s fiscal interest to get the veteran connected with federally funded VA services as quickly as possible. Second, the VA has seen a large influx of resources (for example, vouchers for housing and services) as a result of the 2009 federal government mandate to end veteran homelessness. Outreach workers are aware that while overall funding for homeless populations may be limited, there is a pool of resources at the VA that can facilitate veterans’ transition to stable housing, and thus they are quick to make the appropriate referrals.

Data Analysis

The qualitative data analysis used 336 transcripts or typed notes, most of which were drawn from focus group data collections. These documents were uploaded into an NVivo 10 database (a computer software tool used for qualitative analysis) for review and coding. The key characteristics of the interviews and respondents, such as whether they were staff or veterans or VA mental health service users, and the interview locations (for example, VISN number, type of facility or organization in which the interview took place) were linked to the documents so that the data could be examined for varying themes between the different types of respondents.

After an initial review of the data, Westat’s analytic team worked together to develop a provisional coding structure. High-level or “parent codes” generally reflected key research questions (for example, questions concerning access and barriers to care). Subcodes tended to reflect findings that had been discussed frequently during team meetings (for example, specific barriers, such as childcare, stigma, and military expectations). As the analytic team reviewed and coded their assigned documents, they conferred on needed refinements to the coding structure, and new codes were added when needed to reflect unanticipated ideas or new theoretical insights.

LITERATURE REVIEW METHODS

The committee identified and reviewed numerous sources of existing literature to provide the support and background information that is present throughout the other chapters in this report. Relevant studies in the peer-reviewed literature, applicable VA (and other government agency) reports, Internet resources, congressional testimony, private-sector reports, recent relevant National Academies reports, and some grey literature were reviewed and considered. The committee also heard presentations from VA officials and other subject-matter experts. The National Academies staff, in consultation with the committee, completed extensive literature searches at the beginning of the study (April 2014) and yearly thereafter (January 2015, January 2016, and January 2017). Databases searched included Pubmed, Ovid Medline, and PsycInfo. Additionally, NCIS, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, RAND, the VA Office of Inspector General, the Government Accountability Office, and the Congressional Research Service were searched for relevant titles. Searches were limited to studies published in English since October 2001. Search terms used were broad: veterans AND (mental health OR behavioral health OR psychological health). After each search, the committee members, with the assistance of National Academies’ study staff, reviewed the abstracts to determine which studies from the literature should be included in this evaluation. Additional targeted topical searches were completed during the study. In total, approximately 8,500 abstracts were reviewed, of which approximately 3,000 full text articles and reports were selected for consideration. Throughout the study, the committee requested and received additional information from the VA. The information submitted by the VA can be accessed at http://www8.nationalacademies.org/cp/projectview.aspx?key=49582 (accessed January 3, 2018).

STUDY LIMITATIONS

As described above, the committee used three major types of sources to gather data for this study: conducting a survey of veterans who use and do not use VA mental health services; conducting multiple site visits around the nation to talk with veterans, their families and caregivers, and mental health providers about VA’s mental health services; and conducting a review of literature that is relevant to the study task. By using this three-pronged strategy, the committee was able to collect a large amount of information with which to address its task. It is important to note, however, that each data source (the

survey, the site visits, and the literature review) has its own limitations, which are discussed below. An overall limitation of the study is that during the 4 years that the committee was collecting information and evaluating the VA’s mental health services, the VA was making changes to its services. To obtain the most up-to-date information possible, the committee made numerous requests to the VA, and the VA provided the updated information. The committee, however, acknowledges that additional changes to VA’s mental health services may have occurred prior to publication of this report and are not captured in it.

The accuracy and precision of the survey findings presented in this report may be limited by the major sources of errors that potentially affect all population-based survey data collections. The potential errors include errors caused by coverage biases in the sample frame, errors caused by sampling variation in the observed data, errors caused by selective bias due to survey noncontact or noncooperation, and measurement errors of the sort that can appear when one is dealing with complex constructs such as mental health symptoms measures and the nature and severity of mental health risk factors. With the assistance of the VA, Westat survey statisticians were able to acquire a comprehensive sample frame for the study and to design and implement an efficient two-phase stratified random sample of the target populations of deployed and non-deployed veterans. However, the substantial rates of noncontact and nonresponse during the survey data collection affected the precision of the estimates and potentially even the inherent representativeness of the sample of veterans who were ultimately interviewed for the survey. Chapter 6 discusses the estimates of demographic and military characteristics derived from the committee’s survey (see Tables 6-1 and 6-2) compared with estimates produced by the VA for the post-9/11 veteran population.

Despite rigorous protocols for tracing and contacting the selected probability sample of veterans, the final combined AAPOR RR2 response rate for the survey was 22.0 percent—roughly half that anticipated at the time the survey was designed. The shortfall in the anticipated response rate may be attributed in part to the fact that the first- and second-phase sample frame provided to Westat did not include mailing address, telephone number, or e-mail address contact information for the individual veterans. The contact information needed to send the survey request to the sampled veterans was obtained by linking to address and telephone number information available for the general population from a commercial source. Other possible explanations for not achieving the targeted response rate include veteran privacy and confidentiality concerns and low saliency of the survey topic for veterans who do not experience mental health symptoms or use VA services for physical or mental health care. The lower-than-expected response rate resulted in a final observed sample size of n = 4,059 cases as compared to the expected sample yield of n = 8,900 completed interviews. Relative to the precision of estimates expected at the design stage of the survey, this translated to roughly a 50 percent increase in the size of the standard errors for descriptive estimates for the total veteran population and its major subclasses.

As detailed in Appendix A, the response rate for sample veterans who were never deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan was 17 percent (AAPOR RR3). Since the stratum of non-deployed, non-VA users comprised 7,855 cases in the original study sample of 19,200 veterans, the impact of this group of sample veterans on the final overall response rate was substantial. Furthermore, as mentioned above, the VA-supplied frame for the veterans included no information on demographic or service characteristics, further reducing the capability to use such population controls in the development of non-response and post-stratification adjustments. Final AAPOR RR3 response rates for the sample strata that included VA users and non-users who had deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan ranged from 17 to 32 percent. Survey response rates were lowest for the stratum of non-deployed veterans and also for deployed veterans who were younger in age and lower in rank at separation from service.

Weighting adjustments for non-response and post-stratification were developed to compensate for differential response by sample veterans belonging to different demographic, service characteristics, and VA-user status groups. The analysis of non-response bias is summarized in Appendix A and demonstrates that for these major factors, the compensatory weighting attenuates much of the bias observed when comparing weighted estimates to the information available for the population on the sample frame. Additional analysis for veterans who are known users of VA services suggests that the weighting of the sample respondent data attenuates major differences on frequency and type of service use for the total eligible population of veterans who use these services. Despite these encouraging results from the nonresponse analysis, due to the low response rate for the survey the potential for non-response bias in survey results for different subpopulations and different variables remains a caution to note in the overall interpretation of study findings.

Key survey measures that form the basis for the many statistical summaries presented in this report are potentially susceptible to various forms of measurement error, including the potential for recall bias and the “telescoping” of time frames in their survey reports. There is also the possibility that the survey scales that aim to capture complex constructs such as mental health symptomatology, the use of services, or experience in combat or with traumatic events may in some cases have misclassified the true states or risk factor exposures of the individual veterans. Throughout the process of developing the survey questionnaire and selecting the items to include in the survey, great care was taken by the committee and the Westat team to rely on validated scales and measures or to use question items that had been previously used in other surveys of veterans and the general population. Cognitive interviewing and pretesting with a small number of veteran volunteers during the questionnaire development process further served to identify and correct major problems with the measures prior to the actual fielding of the final survey instrument.

The 21 site visits conducted as part of the data-gathering efforts for this study provided the committee with valuable qualitative information on OEF/OIF/OND veterans’ experiences regarding access to VA mental health care services and the quality of those services. The number of participants interviewed over the course of the site visits was large (nearly 1,500 people were interviewed) and diverse. The interviewees included women and men, racial and ethnic minorities, and veterans from all service branches. There were several limitations to the site visits. The interviewees represent a self-selected sample; in other words, people often opted to speak with the site visitors for a specific reason (for example, a negative experience using VA mental health care services). Due to time and cost constraints, it was not feasible to conduct follow-up interviews or to do multiple in-depth interviews with participants. For the same reasons, each site visit was limited to about 4 days and, therefore, not all potential sites and interviewees within each VISN could be visited. In some cases, because of scheduling conflicts not all potential interviewees could participate in the site visits. The recruitment of interviewees often relied on contact persons in each locale who were willing to assist the site visitors, and the level of assistance varied from site to site. Therefore, in some locations, recruiting interviewees was challenging. Finally, it is possible that some potential interviewees may not have participated because they did not want to criticize the VA, or some who did participate may not have felt comfortable making negative statements about the VA during group discussions.

Literature searches were conducted near the beginning of this study (early in 2014) and annually thereafter. Studies on the VA’s mental health services and other relevant articles are published by researchers on an ongoing basis, and it is possible that relevant studies published after the committee’s final literature search have not been captured in this report.

REFERENCES

Kalton, G. 1983. Compensating for missing survey data. Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan.

Kass, G. V. 1980. An exploratory technique for investigating large quantities of categorical data. Applied Statistics 29(2): 119–127.

King, L. A., D. W. King, D. S. Vogt, J. Knight, and R. E. Samper. 2006. Deployment risk and resilience inventory: A collection of measures for studying deployment-related experiences of military personnel and veterans. Military Psychology 18(2):89–120.

Vogt, D., B. N. Smith, L. A. King, D. W. King, J. Knight, and J. J. Vasterling. 2013. Deployment Risk and Resilience Inventory-2 (DRRI-2): An updated tool for assessing psychosocial risk and resilience factors among service members and veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress 26(6):710–717.