A.1

NEUROCOGNITIVE MECHANISMS IMPLICATED IN INCREASING THE RISK FOR VIOLENCE

R. James R. Blair1

1 National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, MD

Correspondence to:

R. James R. Blair, PhD

9000 Rockville Pike

Bldg. 15k, Room 205, MSC 2670

Bethesda, MD 20892

jamesblair@mail.nih.gov

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health, under grant number 1-ZIA-MH002860 to James Blair.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Introduction:

Distinguishing Forms of Violence

The goal of this brief review is to consider neurocognitive mechanisms that, when dysfunctional, have been suggested to increase the risk for violence. However, before this can be considered it is worth noting that, from a neuroscience perspective, there appears to be more than one form of violence (Blair, 2001). Specifically, a distinction should be drawn between reactive (affective/defensive/impulsive) and instrumental (proactive/planned) aggression (Crick and Dodge, 1996).

Reactive aggression is unplanned and can be characterized as impulsive. It is explosive, involves the active confrontation of the victim and is typically accompanied by negative affect (anger, sadness, frustration, and irritation). One notable feature distinguishing reactive aggression in humans from that studied in animals is that in humans, it is often associated with frustration (Berkowitz, 1993). Frustration occurs when an individual continues to do an action in the expectation of a reward but does not actually receive that reward (Berkowitz, 1993).

Instrumental aggression in contrast is planned. It involves the selection of a behavior (a covert or overt aggressive response) in anticipation of a positive outcome (e.g., acquisition of territory or goods, improvement of

social status, or gratification of a perceived need). Typically, there is an absence of accompanying intense emotion.

Different psychiatric conditions are associated with risks for different forms of aggression. Thus, patients with mood and anxiety conditions (e.g., posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD]), as well as patients with intermittent explosive disorder (IED) and borderline personality disorder (BPD), are at increased risk for reactive aggression. In contrast, individuals with the personality disorder psychopathy, who show reduced guilt and empathy, show an increased risk for instrumental aggression coupled with an increased risk for reactive aggression (Frick et al., 2005). Importantly, a common pathophysiology likely underpins the increased risk for reactive aggression in PTSD, IED, and BPD (even if there are other aspects of pathophysiology that are idiosyncratic to the individual disorders). In contrast, a rather different pathophysiology likely underpins the increased risk for instrumental aggression in individuals with psychopathic traits.

A System Mediating Reactive Aggression:

Acute Threat Response

The acute threat response involves freezing to a distal threat, fleeing if the threat approaches, and fighting if the threat is very proximal (Blanchard et al., 1977). As such, reactive aggression can be considered the ultimate response to extreme threat. Considerable work with animals has determined that the acute threat response is mediated by a neural circuit that runs from the medial amygdala downward, largely via the stria terminalis to the medial hypothalamus, and then the dorsal half of the periaqueductal gray (Panksepp, 1998; Gregg and Siegel, 2001). This circuitry is assumed to mediate reactive aggression in humans as well (Blair, 2001). In a healthy individual, a very high level of threat might initiate reactive aggression. However, it is suggested that certain clinical conditions lead to lower levels of threat having the same consequence. This is because prior priming of the circuitry, as a consequence of the clinical condition, means that a less intense threat is necessary to initiate reactive aggression (Blair, 2001).

Several psychiatric conditions show a significantly increased risk for reactive aggression. These include PTSD, IED, and BPD (Coccaro et al., 2007; New et al., 2009). In line with the suggestions above of a lowered threshold, patients with these clinical conditions all show heightened responsiveness of regions implicated in reactive aggression, particularly the amygdala, to emotional provocation (Coccaro et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2008; New et al., 2009). In addition, patients with BPD have also been found to show an increased amygdala response to interpersonal provocation (New et al., 2009).

Several psychosocial stressors, such as exposure to trauma and neglect, are known to selectively increase the risk for reactive aggression in humans (Crick and Dodge, 1996). Notably, these stressors have also been shown to increase the amygdala response to threat (McCrory et al., 2011; Tottenham et al., 2011). In short, it can be argued that these stressors increase the risk for reactive aggression because they increase the responsiveness of systems mediating the acute threat response. Because of this, the individual is more likely to display reactive aggression in response to future provocation.

Neurocognitive Mechanism That, When Dysfunctional, Increases the Risk for Instrumental Aggression:

Empathic Responsiveness

An association between reduced empathic responsiveness to the distress of others and an increased risk for aggression has long been made (Miller and Eisenberg, 1988). Work has shown that empathic responses to the distress of others diminish aggressive responding (Perry and Perry, 1974). Moreover, empathic responding is critical for socialization. Caregivers most typically respond to transgressions that harm others by focusing on the distress of the victim (Nucci and Nucci, 1982). When this socialization is successful, the individual is less likely to choose actions that will harm others because of the aversive feelings he or she experiences in relation to the anticipated victim’s distress.

Different definitions of empathy have been provided. But the functional processes, with respect to modulating the risk for aggression, concern the impact of distress cues (fearful, sad, and pained facial and vocal expressions) on (1) current behavior by interrupting it; and (2) future behavior by guiding, through social learning, the individual away from behavioral choices associated with harm to others. The amygdala is considered to be critical for both these processes. Considerable data show that the amygdala is responsive to fearful expressions (Adolphs, 2010) and, to a lesser extent, sad and pained expressions. Activation of the amygdala initiates freezing—interrupting current behavior. In addition, the amygdala is important for social learning. The amygdala enables the association of stimuli with the aversive reinforcement engendered by the fear of others (Jeon and Shin, 2011). This social learning means that the healthy individual comes to value actions that harm other individuals as aversive (Blair, 2013).

Deficient empathy is associated with conduct disorder (CD), particularly that associated with psychopathic traits, including reduced guilt (Blair, 2013). Such patients show reduced physiological responsiveness to expressions of distress in peers (Blair, 1999; de Wied et al., 2012). In addition, they show reduced amygdala responses to fearful and sad expressions, as well as the pain of others (Marsh et al., 2008; Viding et al., 2012; White

et al., 2012). The presence of psychopathic traits, particularly reduced guilt and empathy, are associated with an increased risk for instrumental aggression (Cornell et al., 1996). The suggestion is that the individual with psychopathic traits is less likely to stop aggressing in response to the victim’s distress because there is less amygdala activity and consequent freezing. In addition, such an individual is less guided away from actions that harm others because he or she has less learned the aversive value of actions that harm others. In line with this, individuals with psychopathic traits have been found to show greater indifference to transgressions that harm others (Aharoni, Antonenko, and Kiehl, 2011; Blair, 1995) and reduced amygdala responses to such transgressions (Glenn, Raine, and Schug, 2008). Such indifference means that the individual is more likely to commit an action that will harm others to achieve his or her goals.

Neurocognitive Mechanism That, When Dysfunctional, Increases the Risk for Reactive and Instrumental Aggression:

Reward–Punishment-Based Decision Making

Problems in reward–punishment-based decision making are likely to increase the risk for reactive and instrumental aggression in several ways. First, individuals who fail to learn how to obtain rewards and avoid punishments through their decisions face high risk for impulsivity and frustration. Both impulsivity and frustration, in turn, predict risk for reactive aggression (Berkowitz, 1974). Second, it is suggested that systems involved in decision making are also involved in the regulation of the acute threat response. Specifically, ventromedial frontal cortex is involved in the selection of appropriate action as a function of the value outcomes associated with different behavioral choices (a critical component of reward–punishment-based decision making). An angry reactive response to provocation may not be selected if the negative value of the detrimental consequences of this action is appropriately represented (e.g., costs of imprisonment). Third, and relatedly, instrumental aggressive responses will be less likely to be selected if the negative values of their detrimental consequences are represented (e.g., victim’s distress, and costs of imprisonment).

Systems neuroscience research links specific forms of decision making, involving reinforcement-based learning, to a circuit that connects the striatum, amygdala, and ventromedial frontal cortex as well as other structures (O’Doherty, 2012). Patients with conduct disorder exhibit a form of impaired decision making associated with dysfunction in this neural circuit. For example, they are more likely to respond to stimuli that engender punishment or continue to respond to stimuli that, while once rewarding, now engender punishment (Crowley et al., 2010; Finger et al., 2008; White et al.,

2013). Notably, such forms of impaired decision making occur in conduct disorder either with or without high levels of callous and unemotional traits (White et al., 2013), as well as in patients with ADHD without conduct disorder (Plichta et al., 2009; Scheres, Milham, Knutson, and Castellanos, 2007; Strohle et al., 2008). Moreover, they may occur in unaffected but at-risk children, born to parents with their own histories of conduct problems or drug addiction (Yau et al., 2012). Thus, impaired decision making arising from fronto-striatal dysfunction may represent a shared substrate for frequently comorbid disorders, such as conduct disorder, ADHD, and substance use disorders.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this review outlines three neurocognitive systems that, when dysfunctional, increase the risk for aggression. These are (1) the acute threat response implicating the amygdala, hypothalamus, and periaqueductal gray; (2) empathic responding (instrumental) implicating the amygdala and, in the context of decision making influenced by empathy for potential victims, ventromedial frontal cortex; and (3) reward–punishment-based decision making implicating striatum and ventromedial frontal cortex. Importantly, identifying these systems provides treatment targets. Interventions can be designed to address the functioning of these systems and their efficacy, indexed by their impact on the systems themselves, as well as downstream consequences of reduced aggression.

References

Adolphs, R. (2010). What does the amygdala contribute to social cognition? Ann N Y Acad Sci, 1191, 42-61. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05445.x.

Aharoni, E., Antonenko, O., and Kiehl, K. A. (2011). Disparities in the moral intuitions of criminal offenders: The role of psychopathy. J Res Pers, 45(3), 322-327. doi: 10.1016/j. jrp.2011.02.005.

Berkowitz, L. (1993). Aggression: Its causes, consequences, and control. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Berkowitz, L. (1974). Some determinants of impulsive aggression: Role of mediated associations with reinforcements for aggression. Psychological Review, 81, 165-176.

Blair, R. J. R. (1995). A cognitive developmental approach to morality: Investigating the psychopath. Cognition, 57, 1-29.

Blair, R. J. R. (2001). Neurocognitive models of aggression, the antisocial personality disorders, and psychopathy. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 71(6), 727-731.

Blair, R. J. (2013). The neurobiology of psychopathic traits in youths. Nat Rev Neurosci, 14(11), 786-799. doi: 10.1038/nrn3577.

Blair, R. J. R. (1999). Responsiveness to distress cues in the child with psychopathic tendencies. Personality and Individual Differences, 27, 135-145.

Blanchard, R. J., Blanchard, D. C., and Takahashi, L. K. (1977). Attack and defensive behaviour in the albino rat. Animal Behavior, 25, 197-224.

Blanchard, R. J., Takahashi, L. K., and Blanchard, D. C. (1977). The development of intruder attack in colonies of laboratory rats. Animal Learning and Behavior, 5(4), 365-369.

Coccaro, E. F., McCloskey, M. S., Fitzgerald, D. A., and Phan, K. L. (2007). Amygdala and orbitofrontal reactivity to social threat in individuals with impulsive aggression. Biological Psychiatry, 62(2), 168-178.

Cornell, D. G., Warren, J., Hawk, G., Stafford, E., Oram, G., and Pine, D. (1996). Psychopathy in instrumental and reactive violent offenders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64, 783-790.

Crick, N. R., and Dodge, K. A. (1996). Social information-processing mechanisms in reactive and proactive aggression. Child Development, 67(3), 993-1002.

Crowley, T. J., Dalwani, M. S., Mikulich-Gilbertson, S. K., Du, Y. P., Lejuez, C. W., Raymond, K. M., and Banich, M. T. (2010). Risky decisions and their consequences: Neural processing by boys with Antisocial Substance Disorder. PLoS ONE, 5(9), e12835. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012835.

de Wied, M., van Boxtel, A., Matthys, W., and Meeus, W. (2012). Verbal, facial and autonomic responses to empathy-eliciting film clips by disruptive male adolescents with high versus low callous-unemotional traits. J Abnorm Child Psychol, 40(2), 211-223. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9557-8.

Finger, E. C., Marsh, A. A., Mitchell, D. G. V., Reid, M. E., Sims, C., Budhani, S., . . . Blair, R. J. R. (2008). Abnormal ventromedial prefrontal cortex function in children with psychopathic traits during reversal learning. Archives of General Psychiatry, 65(5), 586-594.

Frick, P. J., Stickle, T. R., Dandreaux, D. M., Farrell, J. M., and Kimonis, E. R. (2005). Callous-unemotional traits in predicting the severity and stability of conduct problems and delinquency. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 33(4), 471-487.

Glenn, A. L., Raine, A., and Schug, R. A. (2008). The neural correlates of moral decision-making in psychopathy. Molecular Psychiatry, 14, 5-6.

Gregg, T. R., and Siegel, A. (2001). Brain structures and neurotransmitters regulating aggression in cats: Implications for human aggression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biological Psychiatry, 25(1), 91-140.

Jeon, D., and Shin, H. S. (2011). A mouse model for observational fear learning and the empathetic response. Curr Protoc Neurosci, Chapter 8, Unit 8 27. doi: 10.1002/0471142301. ns0827s57.

Lee, T. M. C., Chan, S. C., and Raine, A. (2008). Strong limbic and weak frontal activation to aggressive stimuli in spouse abusers. Molecular Psychiatry, 13(7), 655-656.

Marsh, A. A., Finger, E. C., Mitchell, D. G. V., Reid, M. E., Sims, C., Kosson, D. S., . . . Blair, R. J. R. (2008). Reduced amygdala response to fearful expressions in children and adolescents with callous-unemotional traits and disruptive behavior disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 165(6), 712-720.

McCrory, E. J., De Brito, S. A., Sebastian, C. L., Mechelli, A., Bird, G., Kelly, P. A., and Viding, E. (2011). Heightened neural reactivity to threat in child victims of family violence. Curr Biol, 21(23), R947-948. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.10.015.

Miller, P. A., and Eisenberg, N. (1988). The relation of empathy to aggressive and externalizing/antisocial behavior. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 324-344.

New, A. S., Hazlett, E. A., Newmark, R. E., Zhang, J., Triebwasser, J., Meyerson, D., Lazarus, S., Trisdorfer, R., Goldstein, K. E., Goodman, M., Koenigsberg, H. W., Flory, J. D., Siever, L. J., and Buchsbaum, M. S. (2009). Laboratory induced aggression: A positron emission tomography study of aggressive individuals with borderline personality disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 66(12), 1107-1114.

Nucci, L. P., and Nucci, M. (1982). Children’s social interactions in the context of moral and conventional transgressions. Child Development, 53, 403-412.

O’Doherty, J. P. (2012). Beyond simple reinforcement learning: The computational neurobiology of reward-learning and valuation. Eur J Neurosci, 35(7), 987-990. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2012.08074.x.

Panksepp, J. (1998). Affective neuroscience: The foundations of human and animal emotions. New York: Oxford University Press.

Perry, D. G., and Perry, L. C. (1974). Denial of suffering in the victim as a stimulus to violence in aggressive boys. Child Development, 45, 55-62.

Plichta, M. M., Vasic, N., Wolf, R. C., Lesch, K. P., Brummer, D., Jacob, C., . . . Gron, G. (2009). Neural hyporesponsiveness and hyperresponsiveness during immediate and delayed reward processing in adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry, 65(1), 7-14. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.07.008.

Scheres, A., Milham, M. P., Knutson, B., and Castellanos, F. X. (2007). Ventral striatal hyporesponsiveness during reward anticipation in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry, 61(5), 720-724. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.04.042.

Strohle, A., Stoy, M., Wrase, J., Schwarzer, S., Schlagenhauf, F., Huss, M., . . . Heinz, A. (2008). Reward anticipation and outcomes in adult males with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuroimage, 39(3), 966-972. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.09.044.

Tottenham, N., Hare, T. A., Millner, A., Gilhooly, T., Zevin, J. D., and Casey, B. J. (2011). Elevated amygdala response to faces following early deprivation. Dev Sci, 14(2), 190-204. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2010.00971.x.

Viding, E., Sebastian, C. L., Dadds, M. R., Lockwood, P. L., Cecil, C. A., De Brito, S. A., and McCrory, E. J. (2012). Amygdala response to preattentive masked fear in children with conduct problems: The role of callous-unemotional traits. Am J Psychiatry, 169(10), 1109-1116. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12020191.

White, S. F., Marsh, A. A., Fowler, K. A., Schechter, J. C., Adalio, C., Pope, K., . . . Blair, R. J. R. (2012). Reduced amygdala responding in youth with disruptive behavior disorder and psychopathic traits reflects a reduced emotional response not increased top-down attention to non-emotional features. American Journal of Psychiatry, 169(7), 750-758.

White, S. F., Pope, K., Sinclair, S., Fowler, K. A., Brislin, S. J., Williams, W. C., . . . Blair, R. J. R. (2013). Disrupted expected value and prediction error signaling in youth with disruptive behavior disorders during a passive avoidance task. American Journal of Psychiatry.

Yau, W. Y., Zubieta, J. K., Weiland, B. J., Samudra, P. G., Zucker, R. A., and Heitzeg, M. M. (2012). Nucleus accumbens response to incentive stimuli anticipation in children of alcoholics: Relationships with precursive behavioral risk and lifetime alcohol use. J Neurosci, 32(7), 2544-2551. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.1390-11.2012.

A.2

VIOLENCE AND MENTAL HEALTH:

OPPORTUNITIES FOR PREVENTION AND EARLY INTERVENTION, A WORKSHOP OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES OF SCIENCES, ENGINEERING, AND MEDICINE’S FORUM ON GLOBAL VIOLENCE PREVENTION, FEBRUARY 26, 2014

Presentation by Daniel Fisher, M.D.,

Executive Director, National Empowerment Center,

25 Bigelow St., Cambridge, MA 02139

The very title of this conference saddens me, and makes me angry. Clearly the gun lobby has been effective in changing the narrative from controlling guns to controlling those of us who have been labeled mentally ill. This narrative is based on false information equating persons with mental health disorders with increased violence.

Introduction

In my 20s I was diagnosed with schizophrenia and was involuntarily hospitalized on three occasions. Ironically, I was studying the possible biochemical bases of mental illnesses at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) at the time. (That was in the late ’60s. In May of last year, 45 years later, Dr. Thomas Insel of NIMH stated that NIMH will not use the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition [DSM-5] because its diagnostic categories are not based on biological markers.) I was researching the factors controlling the biosynthesis of dopamine and serotonin. I so reduced human experiences to chemistry that I became convinced that we all were merely chemical machines, and that we lacked meaning or agency. I lost the meaning of human relationships and emotional expression. Being unable to understand communication left me out of touch. I believe this empty view of life and the loneliness it produced left me in despair and caused me to depart from everyday reality. I indeed did fit the DSM definition of schizophrenia. I recovered from schizophrenia by finding meaning through emotionally connecting with others and myself. I concluded that we have a self that supersedes all we can write in a formula. This understanding brought me back to everyday life with people. I decided I could learn more about this human dimension by becoming a psychiatrist,

and have practiced in clinical settings for the last 35 years. I also founded and run the National Empowerment Center, a Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)-funded, technical assistance center dedicated to bringing hope and recovery to the mental health system and society.

Recovery depends on people with mental illness finding meaningful relationships and working in the community. The misinformation perpetuated by our media is interfering with recovery. This incorrect coupling of mental health issues with violence increases prejudice and discrimination among all members of society. (Advocates are rejecting the use of the term “stigma” because the term itself has produced increased prejudice.)

I will summarize the evidence that people diagnosed with mental health conditions are no more violent than matched community members without such a label. Although there is a lack of association of violence and mental health conditions, the increased attention on mental health can be an opportunity to improve that system. Therefore, I will point out problems in our mental health system and society that are barriers to recovery. Finally, I will recommend ways that our mental health system needs to continue its transformation from a maintenance-based to a recovery-based system.

The Evidence Does Not Link Persons with Mental Health Disorders to Violence

A recently published report by the Consortium for Risk-Based Firearm Policy (2013) concluded: “Research evidence shows that the large majority of people with mental illness do not engage in violence against others and most violence is caused by factors other than mental illness.” The report also found that “research evidence suggests that . . . mental illness alone rarely causes violence.” These conclusions were based on three studies (Elbogen and Johnson, 2009; Swanson et al., 2013; Van Dorn et al., 2012).

This evidence fits closely with the findings of the MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study, considered one of the most definitive published studies of mental health issues and violence. Dr. Heather Stuart (summarized the MacArthur Study as follows: The MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study (Applebaum et al., 2000; Monahan et al., 2001; Steadman et al., 1998, 2000) “has made a concerted effort to address . . . [methodological] problems, so it stands out as the most sophisticated attempt to date to disentangle these complex interrelationships” (Stuart, 2003).

Because they collected extensive follow-up data on a large cohort of subject (N = 1,136), the temporal sequencing of important events is clear. Because they used multiple measures of violence, including patient self-report, they have minimized the information bias characterizing past work. The innovative use of same-neighbor comparison subjects eliminates confound-

ing from broad environmental influences such as socio-demographic or economic factors that may have exaggerated differences in past research.

In this study, the prevalence of violence among those with a major mental disorder who did not abuse substances was indistinguishable from their non-substance abusing neighborhood controls. Delusions were not associated with violence, even ‘threat control override’ delusions that cause an individual to think that someone is out to harm them or that someone can control their thoughts. (Stuart, 2003)

Fazel and colleagues (Fazel et al., 2009a), carried out a meta-analysis of 20 studies that examined a possible relationship of violence to mental health conditions. They concluded that “psychosis comorbid with substance abuse confers no additional risk over and above the risk associated with substance abuse.” This finding was consistent with their own finding that schizophrenia, in the absence of substance abuse, did not increase the risk of violence when compared to the general population (Fazel et al., 2009b).

Therefore, every significant research study carried out starting with the MacArthur Study in the late 1990s has concluded that:

- Persons with mental illness are no more likely than the matched controls in the community [to perform violent acts].

- Persons with a substance abuse disorder carry a substantial risk of increased violence.

Therefore, “Strategies that aim to reduce gun violence by focusing . . . on restricting access to guns by those diagnosed with a mental illness are unlikely to reduce the overall rate of gun violence in the United States” (Consortium for Risk-Based Firearm Policy, 2013).

The National Instant Background Check System, NICS, should be focused on dangerousness and a history of violence rather than a mental health diagnosis per se (Consortium for Risk-Based Firearm Policy, 2013). After all, those of us diagnosed with a mental health disorder account for only 4 percent of the gun-related homicides (Swanson et al., 2013).

Our Mental Health System Is Not a Welcoming Place

It is dehumanizing, and hope-robbing approaches are major reasons why it is broken. It could practice hospitality, like hotels, through the practice of dialogue. Instead it practices varying degrees of coercion, persuasion, and suggestion. These all are forms of trauma. To be trauma-informed, we need to adhere to principles of dialogue emphasizing connecting, especially at the emotional level, mutual respect for the full humanity of the person

in distress and listening to his or her voice, believing in them, and giving them hope and humility. Peers can greatly enhance these qualities when their roles as recovery coaches are valued and understood.

Our Deeper Malaise

Rather than focus on our mental health system alone, I want to point out that dehumanizing labels and coercion are a reflection of a deeper woe, that is, the breakdown of cohesion in our communities. The fear in our society of people who are different or odd is the basis for such reactions. We desperately need to rebuild positive connections to each other in our communities. Cross-cultural studies have shown that contact with people of differing race and culture, as well as mental health issues, is a critical factor in becoming more comfortable with them. Contact also decreases prejudice, stigma, and discrimination.

Recommendations

- Broaden the community dialogue on mental health, and ensure that persons with lived experience of mental health conditions are included in the planning and participation of these dialogues.

- NIMH and SAMHSA should promote the training and evaluation of Open Dialogue (Seikkula, 2006) in the United States, to reach people where they live, and while they are still connected to their natural supports. This approach, developed in Finland, is the most successful approach in the world for helping young people who have experienced their first psychotic experience to recover a full life in the community.

- Hiring peers in valued roles as crisis workers and in peer-run respites; peers are capable of reaching persons whom non-peers cannot reach. This is true because when you have experienced delusions and voices, you know how to reach and connect with other persons going through a similar experience. Peer-run respites are a good example of the application of this capacity of peers in diverting persons from hospitalization (see the section on crisis respites at www.power2u.org).

- Training first responders, peers, and families in Emotional CPR. This is a preventative public health program, enabling anyone to help another person through an emotional crisis. eCPR, therefore, represents the type of primary prevention that would reach a much greater proportion of persons than present programs that focus on persons labeled with mental health disorders (see www.emotionalcpr.org).

- Speakers sharing recovery stories in person with media officials, police, parents, and other important community groups. Research has shown that the most effective way to reduce prejudice and discrimination is through people sharing their stories (Corrigan, 2005).

- Educating the media to not continue the misinformation of links between mental health issues and violence (the “See Me” campaign in Scotland is a good example of this media education).

- Continue the transformation from a medical narrative to a recovery narrative that was started in the Surgeon General’s Mental Health Report (1999) and the New Freedom Commission (Fisher, 2008; New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2003).

Comments on Other Talks Given at the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s Workshop on Violence and Mental Health

Dr. Paul Appelbaum pointed out that Wayne LaPierre, vice president of the National Rifle Association (NRA), quickly shifted the blame for the Sandy Hook shootings in December 2012 from guns to persons labeled with mental illness. He said that the problem of gun violence is not guns but people with mental illness, whom he described as “deranged mongrels.” The NRA called for ensuring that persons labeled with mental illness be placed on the National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS). This represented a change in policy of the NRA, which as recently as 2007, had loosened the NICS: “The price for bringing the NRA on board [for the NICS bill of 2007] was to take the ‘mentally ill’ tag away from anyone ‘rehabilitated through any procedure available under law’ and to enact a ‘Relief from Disabilities’ reform. The latter reform allowed people classified as mentally ill, and unable to buy guns, to get their rights back with more ease” (Weigel, 2013).

References

Appelbaum, P.S., Robbins, P.C., Monahan, J. 2000. Violence and delusions: Data from the MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study. Am. J. Psychiatry 157:566-572.

Consortium for Risk-Based Firearm Policy. 2013. Guns, public health and mental illness: An evidence-based approach for state policy. John Hopkins University: Baltimore, MD.

Corrigan, P. 2005. On the stigma of mental illness: Implications for research and social change, fifth edition. American Psychological Association: Washington, DC.

Elbogen, E., and Johnson, S. 2009. Intricate link between violence and mental disorder results from national epidemiological survey on alcohol and related conditions. Archives General Psychiatry 66:152-161.

Fazel, S., Gulati, G., Linsell, L., Geddes, J.R., and Grann, M. 2009. Schizophrenia and violence: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 6(8): e1000120. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000120.

Fazel, S., Låndström, N., Hjern, A., Grann, M., and Lichtenstein, P. 2009b. Schizophrenia, substance abuse, and violent crime. JAMA 301(19):2016-2023.

Fisher, D.B. 2008. Promoting recovery. Learning about mental health practice. Eds. T. Stickley and T. Basset. John Wiley and Sons: Chichester, U.K. pp. 119-139.

McGinty, E., et al. 2013. Gun policy and serious mental illness: Priorities for future research and policy. Psychiatric Services, epub ahead of print, doi:10.1176/appi. Ps.201300141.

Monahan, J., Steadman, H.J., Silver, E., et al. 2001. Risk assessment: the MacArthur Study of Mental Disorder and Violence. Oxford University Press: Oxford, U.K.

New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. 2003. Achieving the promise: Transforming mental health care in America final report. DHHS Pub. No. SMA-03-3832. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Rockville, MD.

Seikkula, J., and Trimble, D. 2005. Healing elements of therapeutic conversation: Dialogue as an embodiment of love. Family Process 44(4):461-475.

Seikkula, J., Aaltonen, K., Alakare, B., Haarakanga, K., Keranen, J., and Lehtinen, K. 2006. Five-year experience of first-episode nonaffective psychosis in open-dialogue approach: Treatment principles, follow-up outcomes, and two case studies. Psychotherapy Research 16(2):214-228.

Steadman, H.J., Silver, E., Monahan, J., Appelbaum, P.S., et al. 2000. A classification tree approach to the development of actuarial violence risk-assessment tools. Law Humanity Behavior 24:83-100.

Steadman, H.J., Mulvy, E.P., Monahan, J., et al. 1998. Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric inpatient facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Arch Gen Psychiatry 55:393-404.

Stuart, H. 2003. Violence and mental illness: An overview. World Psychiatric Assoc 2:121-124.

Swanson, J. et al. 2013. “Preventing gun violence involving people with serious mental illness.” In Reducing gun violence in America: Informing policy with evidence and analysis. Webster, D. and Vernick, J. eds. Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD. pp. 33-51.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 1999. Mental health: A report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health: Rockville, MD.

Van Dorn, R., Volavka, J., and Johnson, N. 2012. Mental disorder and violence: Is there a relationship beyond substance abuse? Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 47:487-503.

Weigel, D. 2013. CPAC Diary: Wayne LaPierre’s “Mental Health” Chutzpah. Slate Magazine, March 15.

A.3

INTERFACE WITH THE JUSTICE COMMUNITY: THE POLICE

Sheldon Greenberg, Ph.D.

Johns Hopkins University

Despite the long-term call by criminal justice and mental health professionals, advocates, and political officials to work together more effectively in providing services to people with mental illness, progress in many jurisdictions (cities, counties, towns, states, tribal land) and nations has been slow. This paper presents and expands on a portion of the information presented during the workshop titled Mental Health and Violence: Opportunities for Prevention and Early Intervention. It offers information on the interface between the criminal justice and mental health communities, addresses some of the reasons for measured progress, and suggests ways in which the two professions might advance success. While this paper briefly addresses public safety, including corrections, it focuses primarily on interaction among the police, mental health providers, and people who have mental illness and their families, friends, and other advocates.

For decades, mental health professionals, advocacy organizations, family members, political leaders, and others have sought to have the criminal justice system or criminal justice community (generally perceived as consisting of the police, courts, and corrections) end the unnecessary “criminalization” of mental illness. This continues to be a priority.

Generally, an arrest is defined as the taking of a person into custody by a legal authority, usually in response to a criminal charge. The criminalization hypothesis is based on the assumption that police inappropriately use arrest to resolve encounters with people who have mental illness (Engel and Silver, 2001). Criminalization that can affect the future of a person with mental illness goes beyond traditional arrest and may include criminal citations (usually issued for minor offenses that do not require taking a person into custody) and inclusion of names in criminal incident reports.

Terms such as “criminal justice system” and “criminal justice community” suggest that there is a common foundation of standards, policies, practices, and other linkages across the profession. In fact, criminal justice in the United States and in many other nations is a highly fragmented, parochial, and compartmentalized and, at times, is a competitive collection of local, state, tribal, and federal agencies. There is no central organization, professional association, or other body with the authority to mandate policy, practice, or change. As of 2011, there were approximately 15,000 local police departments in the United States. The majority of these agencies

have fewer than 25 personnel. Fewer than 70 agencies serve jurisdictions with large populations (500,000 or more) (Baltic, 2011). Fragmentation exists in other nations as well, although some nations have a single national police force (France, Italy, Japan, New Zealand, Nicaragua) or a small number of agencies (Sweden, United Kingdom), and other nations’ law enforcement services are provided by their defense agency/military (Chilean Carabineros).

For a brief perspective on the larger justice system in the United States, there are 3,365 local jails, not including state, federal, military, or juvenile correctional institutions. Data on the number of courts—federal, state, local, military, and specialized—are weak, although it is estimated that there are more than 3,000 trial court judges serving the nation. The global criminal justice system is diverse, and the concept of justice (fair processes, just outcomes, respect for human rights and dignity, upholding law) is too varied and complex in some nations and ill-defined in others to describe adequately in this paper (Nagel, 2005).

Since the period of deinstitutionalization (intended to close large, often antiquated public mental health hospitals and ensure the transfer of patients to community-based mental health services) that began in the mid-1950s and increased continually through the 1980s, criminal justice agencies have altered policies, procedures, training, and relationships with mental health providers and advocates to overcome difficulties stemming from critical and routine interaction with people who have severe mental illness (Lurigio and Swartz, 2000). When deinstitutionalization began in 1955, there were approximately 560,000 severely mentally ill patients in the nation’s public psychiatric hospitals. By 1994, this number was reduced by more than 485,000 patients to approximately 72,000 (Frontline, 2005). Several failed federal acts and the weak community response to supporting those who returned to the community placed new and immediate burdens on the police, courts, and corrections. Similar experiences occurred in other nations and continents, including Australia, New Zealand, and Western Europe (Fakhoury and Priebe, 2002). Two significant consequences of deinstitutionalization have been the “criminalization of mental illness” (Peternelj-Taylor, 2008) and victimization of people who have mental illness (Teplin et al., 2005).

In considering the interface with the criminal justice system by mental health providers, public health, social services, the faith community, and other organizations, it is essential to focus on the role of the frontline police officer as the “point of entry” and “point of diversion” toward or away from arrest, prosecution, and incarceration. Generally, a police officer’s decision to connect with a mental health service provider or other support service, arrest (criminalize), pursue hospitalization or other placement, or handle the call informally is based primarily on the characteristics and

constraints of each situation rather than the symptomatology or awareness of mental illness (Lamb et al., 2002; Teplin, 2000). Action and decisions by prosecutors and the courts will be determined, in great part, by the actions and reports of the responding police officers.

Police agencies have sought to improve response to calls for service and other incidents involving people with mental illness, especially those considered crisis or emergency situations. These new developments (training, advances in policy, scrutiny of arrests, crisis intervention teams), however, have been targeted almost exclusively at improved handling of individual incidents. Less attention has been devoted to developing or implementing comprehensive, multiagency, and preventive approaches (Cordner, 2006).

Generally, police become involved in situations and interact with people who have mental illness when problems surface (Cordner, 2006). One three-city study found that 92 percent of uniformed patrol officers had at least one interaction with a person experiencing a mental health crisis in the previous month. Police officers report that they are involved in an average of six calls per month specifically related to people with mental illness (Borum, 2000; Vermette et al., 2005). An estimated 7 percent of police contacts in jurisdictions with 100,000 or more involve people with mental illness (Deane et al., 1999). The above data are based on reported incidents. A significant percentage of a police officer’s interaction, intervention, and problem-solving activity never makes its way into police reports and is never captured in the data. Such activity is not found in the reported data for several reasons: the situation requiring police intervention may have been resolved quickly or informally; the officer did not want the involved individuals to be named in a report; and/or the information may have been recorded according to the initial call (assault, domestic situation, suspicious activity, injured person), with no identifiers related to mental illness. In some cases, the officer simply may have chosen not to file a formal report.

Research shows consistently that police officers do not want to criminalize events involving people with mental illness unless significant violation of the law has occurred (assault, theft, arson, weapons violation) and cannot be ignored or handled less formally. Officers express frustration in handling calls involving people with mental illness because of the lack of needed information, the lack of immediately available resources, and the lack of coordination in effort between police and mental health professionals (Engel and Silver, 2001; Novak and Engel, 2005; Wells and Schafer, 2006).

There is minimal research on the face-to-face interaction among the first-responding patrol officer, the person who has mental illness, family members, and others. Little is known about what occurs in the first moments of a situation that drives the involved players toward pursuing informal deescalation, or more formal interventions, such as criminalization, a call for response by mental health professionals, commitment/hospitalization, or

other interventions or diversions from the criminal justice system (Tucker, Hasselt, and Russell, 2008).

Notable progress was made with the establishment of Crisis Intervention Teams (CITs) in the late 1980s, which brought together well-trained police officers and mental health professionals to respond immediately to calls for service involving people who have mental illness. Although recognized primarily for intervention in serious or critical situations, CITs responded to any call (crisis and non-critical) in which the caller or responding police officer identified the need for support. These teams primarily appeared in urban and metropolitan environments—Baltimore County, Charlotte-Mecklenburg, Los Angeles, Memphis, and Milwaukee—which had the demand and resources to support them. In some of these jurisdictions, police officers received 40 hours of instruction or more on intervention strategies and often participated in joint training with mental health workers.

Officers who received the training and were assigned to CITs reported improved ability to recognize and respond to calls involving people with mental illness, reduced stereotyping, greater empathy, improved ability to resolve the situation, better communication skills, and increased patience. They further reported that they were less likely to arrest and more prone to redirect the individual toward other forms of support (Hanafi et al., 2008). Importantly, research shows that officers trained to participate in CITs or who received comparable training regarding mental health intervention were less likely than their peers, in some situations, to use force or perceive escalating force as effective in dealing with a person who has mental illness (Compton et al., 2009).

Access to CITs in the United States began declining in recent years, along with other support services, due to local budget crises and federal cost containment strategies (Cunningham et al., 2006). Expansion of CITs is questionable for the foreseeable future.

Training for police personnel remains a void in improving criminal justice service to people who have mental illness. Data on the number of police officers trained are unreliable since some agencies train more than those needed to serve on CITs, and others, especially smaller agencies, rely on other organizations to train their employees. Some agencies do not keep comprehensive data on training provided to their employees. Some states and larger agencies have sought to provide mental health intervention training to a minimum of 20 percent of their officers (Compton et al., 2008). To date, there has been minimal research assessing the quality of CIT and other mental health training provided to police officers, its endurance over time, or the impact it has on outcomes for people who have mental illness and their families (Lord et al., 2011).

Officers assigned to CITs receive training that surpasses the norm for their peers. A survey of 33 state law enforcement certification agencies (Police Officer Standards and Training Commissions [POSTs]), which exist in almost every state in the United States, showed that the average training for police officers on “mental illness” was 9.1 hours. The majority of training courses ranged from 2 to 4 hours, with the shortest course being 50 minutes. These courses included content on awareness and process (policies and procedures for arrest, safety, and commitment to a hospital, shelter, or other care facility). Some of the courses described by the states incorporated mental illness with training on all “special populations,” with no information on time allotted specifically to mental illness. Two states reported that they have no requirement for training on mental illness. Little research is available on training provided to specialized police agencies, such as school police, campus police and security personnel, transportation police, and tribal police. The inconsistency in and minimal amount of training provided to police on service to people who have mental illness is a global issue (Psarra et al., 2008).

Calls are made to the police by people with mental illness who have been victimized, as well as by spouses, other family members, neighbors, mental health professionals, and people who simply observe behavior or an incident but have no relationship to the person with mental illness. The importance of the initial point of contact—often a police or other government call taker/dispatcher—in obtaining critical information and relaying it to the responding police patrol officer cannot be overstated. Despite improved police call-taking protocols, information provided to the police call taker by the victim or observer (witness) is too often brief, panicked, incomplete, and inaccurate. They may only report the immediate need, threat, or danger and fail to mention that a person who has mental illness is involved. As such, the initial information a police officer receives may make no reference to mental illness or contain any details about risk, existing injury or illness, medication use, illicit substance abuse, presence of weapons, or precise location. Officers need, but often lack, information on the individual’s medical or criminal history, cause of the crisis or hostility, prior suicide or self-injury attempts, and attending physicians, among other information (James, 1990). Information provided to a responding police officer may be described as and limited to the following:

- Man injured

- Woman acting out

- Doctor has trouble with patient

- Unknown trouble

- Suspicious circumstance

- Assault

- Threat of assault

- Threat of suicide

- Parent cannot control child

- Disorderly conduct

- Assist with a commitment

Officer safety and the safety of others are paramount when police officers receive a call for service or personally observe an unusual behavior. When information about mental illness is conveyed, no matter how detailed, police officers make assumptions about the potential for danger (Watson et al., 2004).

Lack of Information and Need for Research on Initial Points of Contact

Much of what occurs—including police officers’ discretionary decision making to criminalize or divert from criminalization—is based on the observed behavior, early formulation of perceptions, and communication that occurs in the early moments of the situation. Yet, little is known about the nature and quality of the initial face-to-face interaction of police officers called into situations involving people who have mental illness. Conclusions and assumptions about the early one-on-one interaction that occur are drawn from police incident report narratives, interviews, anecdotal information, and, to a lesser degree, statistical reports, policies and procedures, and training curricula.

There is minimal research on the initial face-to-face interaction (point of contact) between police officers and people who have mental illness. There is little research on the initial interaction between responding police officers and spouses, family members, neighbors, and other involved parties. There is little research on how information conveyed early in a situation might influence, positively or negatively, the re-criminalization of a person with mental illness who had prior contact with the criminal justice system. Research is needed to answer key questions that can possibly lead to more positive courses of action for people with mental illness who are victimized, accused, or perceived as being dangerous to themselves or others:

- What is the level of understanding about the situation by the responding officer before he or she arrives?

- What facts were conveyed to the police department by the caller, and how was this information relayed to the responding officer?

- At what point in the situation does awareness of mental illness become known?

- What co-occurring factors (injury, illicit substance abuse) were apparent at the immediate point of contact?

- What was the real or perceived level of risk of harm (presence of weapons, threats), and how did it evolve?

- How emotional or tense was the situation upon the officer’s arrival?

- What words or actions by the dispatcher, family members, witnesses, and people who have mental illness set the course for police action, particularly the criminalizing or decriminalizing of the situation?

- To what degree did the immediate situation allow for alternatives to criminalization?

- Was information shared about prior history, including incarceration or hospitalization, and what influence did this have on the initial thinking and action by the responding police officer(s)?

- Was the availability (readiness at the time of need) of mental health service providers known to the initial responding officer(s)?

- At what point did police officers connect with a mental health service provider, and what was the nature of their initial information sharing and action planning?

Other Needs to Improve Police Interaction

Other needs and recommendations to improve interaction between the police and people who have mental illness were discussed during a roundtable discussion with public safety practitioners held at The Johns Hopkins University (Division of Public Safety Leadership, 2013). The following reflects some of these needs and recommendations. Due to space limitation, the following recommendations are noted in brief:

- Improved methods for conveying research to frontline practitioners

- Research on point-of-contact communication and other characteristics of initial interaction that influence outcomes

- Orientation/training for mental health professionals on public safety and, particularly, the police (culture, fragmentation, training, policy, safety mandates, discretion, liability)

- Research on the curricula being used to teach the police, with attention to awareness, interaction, use of community-based resources, and law

- Model curricula for police, designed to accommodate the various time limitations imposed by police academy schedules

- Model curricula for police on how to manage concurrent issues (mental illness, mobility or communication disability, criminal behavior, homelessness, substance abuse, injury)

- Model curricula on interacting with people with mental illness who are victimized

- Research on successes, beyond crisis intervention teams, particularly those related to informal diffusion of situations and those in which criminalization did not occur

- Model training and awareness programs, supported by marketing strategies, to educate people who have mental illness and their support network (spouse, family, friends) on interacting with the police, particularly during initial contact

- Advancing call-taker protocols to obtain more and better information from callers to relay to responding police officers and, where joint response occurs, mental health workers or CITs

References

Baltic, S. E. (Ed.). (2011). Crime in the United States 2011. Bernan Press.

Borum, R. (2000). Improving high-risk encounters between people with mental illness and the police. The Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 28(3), 332-337.

Compton, M. T., Bahora, M., Watson, A. C., and Oliva, J. R. (2008). A comprehensive review of extant research on Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) programs. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law Online, 36(1), 47-55.

Compton, M. T., Neubert, B. N. D., Broussard, B., McGriff, J. A., Morgan, R., and Oliva, J. R. (2009). Use of force preferences and perceived effectiveness of actions among Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) police officers and non-CIT officers in an escalating psychiatric crisis involving a subject with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, sbp146.

Cordner, G. (2006). People with mental illness. Problem-oriented guides for police, Problem-Specific Guides Series (40).

Cunningham, P., McKenzie, K., and Taylor, E. F. (2006). The struggle to provide community-based care to low-income people with serious mental illnesses. Health Affairs, 25(3), 694-705.

Deane, M. W., Steadman, H. J., Borum, R., Veysey, B. M., and Morrissey. J. P. (1999). Emerging partnerships between mental health and law enforcement. Psychiatric Services, 50(1), 99-101.

Division of Public Safety Leadership. (2013). Roundtable on Police response to People with Mental Illness. Johns Hopkins University, School of Education, Division of Public Safety Leadership, March 19, 2013, Columbia, Maryland.

Engel, R. S., and Silver, E. (2001). Policing mentally disordered suspects: A reexamination of the criminalization hypothesis. Criminology, 39(2), 225-252.

Fakhoury, W., and Priebe, S. (2002). The process of deinstitutionalization: An international overview. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 15(2), 187-192.

Frontline. (2005). Deinstitutionalization: A Psychiatric “Titanic.” Retrieved from http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/asylums/special/excerpt.html.

Hanafi, S., Bahora, M., Demir, B. N., and Compton, M. T. (2008). Incorporating crisis intervention team (CIT) knowledge and skills into the daily work of police officers: A focus group study. Community Mental Health Journal, 44(6), 427-432.

James, R. (1990). What do police officers really want from the mental health system? Hospital and Community Psychiatry, 41(6), 663.

Lamb, H. R., Weinberger, L. E., and DeCuir, W. J. (2002). The police and mental health. Psychiatric Services, 53(10), 1266-1271.

Lord, V. B., Bjerregaard, B., Blevins, K. R., and Whisman, H. (2011). Factors influencing the responses of crisis intervention team–certified law enforcement officers. Police Quarterly, 14(4), 388-406.

Lurigio, A. J., and Swartz, J. A. (2000). Changing the contours of the criminal justice system to meet the needs of persons with serious mental illness. Criminal Justice, 3, 45-108.

Nagel, T. (2005). The problem of global justice. Philosophy and Public Affairs, 33(2), 113-147.

Novak, K. J., and Engel, R. S. (2005). Disentangling the influence of suspects’ demeanor and mental disorder on arrest. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies and Management, 28(3), 493-512.

Peternelj-Taylor, C. (2008). Criminalization of the mentally ill. Journal of Forensic Nursing, 4(4), 185-187.

Psarra, V., Sestrini, M., Santa, Z., Petsas, D., Gerontas, A., Garnetas, C., and Kontis, K. (2008). Greek police officers’ attitudes towards the mentally ill. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 31(1), 77-85.

Teplin, L. A. (2000). Keeping the peace: Police discretion and mentally ill persons. National Institute of Justice Journal, 244, 8-15.

Teplin, L. A., McClelland, G. M., Abram, K. M., and Weiner, D. A. (2005). Crime victimization in adults with severe mental illness: Comparison with the National Crime Victimization Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(8), 911-921.

Tucker, A. S., Van Hasselt, V. B., and Russell, S. A. (2008). Law enforcement response to the mentally ill: An evaluative review. Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention, 8(3), 236.

Vermette, H. S., Pinals, D. A., and Appelbaum, P. S. (2005). Mental health training for law enforcement professionals. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law Online, 33(1), 42-46.

Watson, A. C., Corrigan, P. W., and Ottati, V. (2004). Police officers’ attitudes toward and decisions about persons with mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 55(1), 49-53.

Wells, W., and Schafer, J. A. (2006). Officer perceptions of police responses to persons with a mental illness. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies and Management, 29(4), 578-601.

A.4

MENTAL HEALTH IN LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN

Dévora Kestel, M.Sc.

Pan American Health Organization

“There is no health without mental health.” Despite this powerful statement, the mental health situation in Latin America and Caribbean countries (LAC) still lags behind where it should and could be. To analyze this situation from a public health perspective, we have selected a few indicators that facilitate the comparison among countries and sub-regions, and that at the same time provide sufficient information to adequately understand the current situation and appreciate potential opportunities from a regional perspective.

Although the general data available from LAC present a situation that could be viewed as dismal, it is important to highlight that there are many good examples in the region worth replicating. There are countries that have been reforming—a continuously ongoing process—their mental health system for decades; there are also regions or towns within countries that use their autonomy to move the mental health agenda forward, even when the national situation is not as advanced.

This brief article intends to highlight some of the most salient features of mental health systems in LAC.

Burden, Prevalence, and Treatment Gap

Recent studies of the global burden of disease show once again the importance of considering mental health as a public health issue (1). Depression is the eleventh cause of disability globally (before TB, diabetes, and lung cancer), and it ranks from third to seventh in the Americas region, depending on the different subregions being considered (2).

Noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) account for 54 percent of the total global health burden, and mental health and substance use disorders and are the biggest contributors to the NCD burden. In LAC, the Disability Adjusted Life Years due to neuropsychiatric disorders amount to 14 percent of the total amount (11 percent mental and behavioral disorders, 3 percent intentional injuries) (1).

Comparing the prevalence of these disorders with the available records of attendance to mental health services allows for the identification of a treatment gap. A treatment gap represents the percentage of people with severe mental disorders that do not receive treatment (3). At the global level, data from 2004 showed the extent of the treatment gap: 35.5 to 50.3 percent of serious cases did not receive any treatment within the prior year in developed countries, but the proportion of cases not receiving any treatment in developing countries was much higher: 76 to 85 percent. These figures clearly indicate how the problem of mental health services availability is not just of concern in developing countries (4).

A recent study of the treatment gap in LAC highlights that 73.5 percent of adults with severe and moderate affective disorders, anxiety disorders, and substance use disorders in the Americas do not receive treatment (47.2 percent in North America, and 77.9 percent in LAC). In the United States, the treatment gap for schizophrenia is 42.0 percent, and in LAC, 56.2 percent (5).

Resources Availability

One partial explanation for this significant gap is the inadequacy of funds available to develop appropriate services for those suffering from mental and neurological disorders. The world median of the health budget allocated to mental health is 2.82 percent (6).

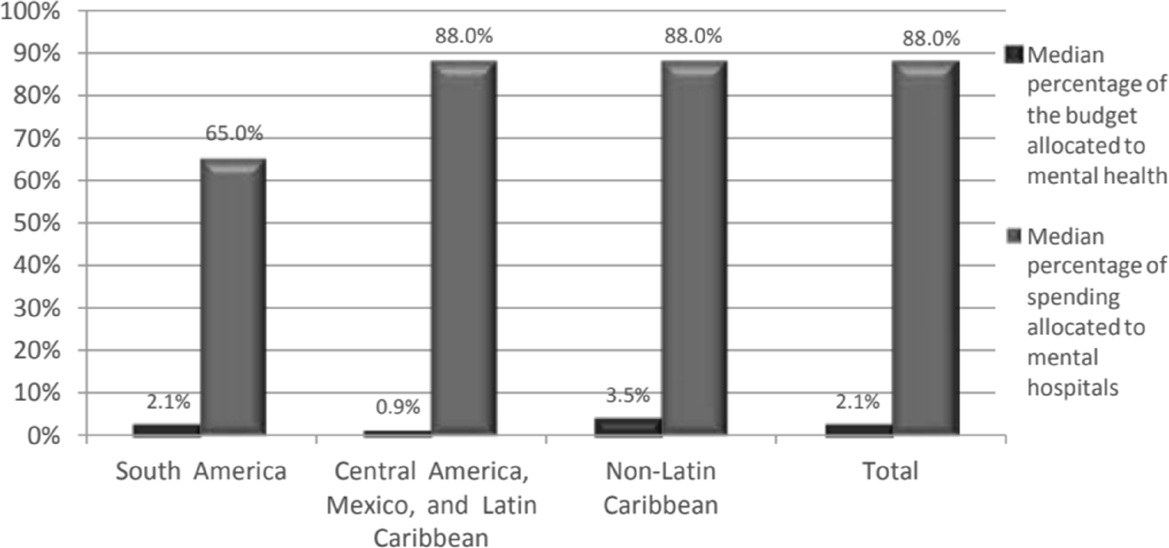

Mental health expenditures at the regional level are not that different from global levels; the median health budget allocated to mental health is 2.3 percent, with differences linked to sub-regional characteristics.

In the context of the existing limited budget environment, it is very important to understand how those resources are used. The principal part of that budget goes to outdated, custodial style, psychiatric hospitals, with very limited funds made available for the development of community-based mental health services. Specifically, in the English-speaking Caribbean countries, the mental health budget is 3.5 percent of the health budget, and 84 percent of that budget goes to mental hospitals. In Central America, the mental health budget is even lower, at 1.5 percent of the health budget, with 75 percent of it spent in mental hospitals. In South America, the budget represents 2 percent of the health budget, with 66 percent going to mental hospitals (7).

Figure A-1 illustrates the median percentage of the government health budget allocated to mental health and to psychiatric hospitals, by subregion and total.

Policies, Plans, and Laws in Mental Health

Having a mental health policy and or a plan (whether it is independent or integrated as part of a general health document is not relevant) is very important to concentrate efforts and available resources into common objectives that will lead to a positive impact on the mental health of the population.

Most of the countries and territories in the region have developed mental health policies and plans; only six of them still do not have such a policy tool. However, having a document written and approved does not necessarily mean that it is being implemented. Several countries have a newly developed mental health policy or plan that advocates for the development of community-based mental health services, while, for example, their services remain concentrated in mental hospitals (7).

Regarding mental health legislation, only eight countries have legislation specific for mental health issued after the year 2000. The implications in this context are related to the lack of appropriate instruments to protect and promote the human rights of the mentally ill and their families.

SOURCE: Figure developed by Dévora Kestel for the WHO-AIMS: Report on Mental Health Systems in Latin America and the Caribbean, by Dévora Kestel, copyright 2013 PAHO. Reprinted with the permission of the Pan American Health Organization.

Mental Health Professionals

Broadly speaking about human resources, there is limited availability of personnel working in mental health. At the global level, there is less than one psychiatrist per 200,000 people or more.

In the LAC region, there are 2.1 psychiatrists per 100,000 people. Although the national average in some countries may not necessarily be small, most of them are frequently concentrated in the capital or main cities of the country, leaving large territories uncovered. Other mental health professionals are generally less present in the region. The presence of nurses, psychologists (with the exception of some countries in South America), social workers, and occupational therapists is quite limited, ranging from around two to less than one professional of each category per 100,000 inhabitants.

Table A-1 below offers a summary of mental health workers available in the LAC region (7).

Organization of Mental Health Services

The analysis of existing services in LAC highlights the inefficiency in the location of beds. Globally, 62 percent of psychiatric beds are located in mental hospitals, with 21 percent in general hospitals, and just 16 percent in residential facilities (6, 7).

TABLE A-1 Mental Health Professionals in LAC

| Subregion | Psychiatrists | Nurses | Psychologists | Social Workers | Occupational Therapists | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central America, Mexico and Latin Caribbean | 1.5 | 2.3 | 2 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 2.3 |

| Non-Latin Caribbean | 1.9 | 14.3* | 0.3 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 20.8 |

| South America | 2.9 | 1.6 | 10.2 | 1.1 | 0.2 | 3.8 |

| Total average | 2.1 | 6 | 4.2 | 1 | 0.2 | 9 |

* A few islands with a small population and a relatively high number of general nurses (all involved with mental health patients) create this high number.

SOURCE: Presented by Dévora Kestel on October 30, 2015.

In LAC, 86.6 percent of the total number of available psychiatric beds are located in psychiatric hospitals, meaning that in many countries, the only answer for people suffering from mental disorders is a bed in a psychiatric hospital, which, in the majority of cases, are outdated custodial institutions that promote a systematic violation of human rights (7).

If a person is in need of hospitalization for an acute episode, he or she would have to access one of the 10.6 percent of the total number of available beds located in general hospitals that are dedicated to psychiatric care (7).

For those persons who may need a longer time to recover without necessarily needing hospital care, they should be considered lucky to access the limited number of beds available in residential facilities (2.7 percent of the total number of available beds) (7).

Paradoxically, when looking at the flow of patients in different mental health facilities, results indicate that those same hospitals that concentrate most of the limited available resources deal with between 5 and 13 percent of the total number of patients who visit any mental health facility in the year assessed. (7) The rest of the patients are seen by ambulatory services, in general hospitals, or in any other service available at the community level, developed with only 12 percent of the budget available for mental health (as mentioned above, 88 percent of the budget dedicated to mental health goes to traditional mental hospitals).

Table A-2 illustrates the number of mental health services’ users, by 100,000 people, visiting available facilities in the year of World Health Organization Assessment Instrument for Mental Health Systems (WHO-AIMS)

TABLE A-2 Number of Users Attending Mental Health Facilities

| Subregion | Outpatient Facilities (median) | Day Hospitals | Psychiatric Units in General Hospitals | Residential Facilities | Psychiatric Hospitals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| South America | 1.232 | 22.3 | 83.3 | 4.7 | 70.72 |

| Central America, Mexico and Latin Caribbean | 588 | 5.1 | 50 | 0.6 | 68 |

| Non-Latin Caribbean | 936 | 7.5 | 119 | 2.5 | 171.4 |

SOURCE: Presented by Dévora Kestel on October 30, 2015.

implementation in their respective country. Although the data collection is not precise (sometimes miscounting a patient with a contact), it nevertheless offers an idea of the patient flow. For instance, looking at South America, 70.72 patients were treated in psychiatric hospitals, while over a thousand were treated in all other services available and developed with very limited resources (7).

Good Experiences in the Region

In 1990, a regional Conference for Restructuring of Psychiatric Care was held in Caracas, Venezuela. That conference is considered to be an important milestone in the region because of its recognition of the need to move the attention, until then primarily focused on the psychiatric hospital, to the development of decentralized, community-based services that are participatory, comprehensive, and that ensure continuity of care. The conference also introduced the need to ensure the protection of patients’ human rights.

Since then, several regional declarations paired with Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) and WHO resolutions have been expanded and approved by member states, all of which aim at the development of a mental health system that will eventually provide an appropriate answer to the mental health needs of the population.

In parallel, several countries in the region are at different stages of serious reforms to their mental health systems, in some cases at the national level, and in others at the regional or even local level.

In October 2013, the World Health Assembly approved a Comprehensive Mental Health Plan of Action that emphasized the need to move ahead in this path that was initiated several years or decades ago (8).

In 2014, PAHO prepared an update to its Regional Mental Health Plan of Action to align it with the global plan. The regional plan is expected to be approved by the Ministers of Health of the Americas by October 2014.

The priorities identified in these plans are concentrated around four main areas:

- Leadership and governance

- Community-based mental health and social care services

- Promotion and prevention

- Information systems, evidence, and research

The adaptation of these plans to national realities should help countries move ahead with needed reforms to their existing mental health services.

Final Considerations

Although countries are moving toward the development of community-based mental health services that are decentralized and closer to people’s realities, there is still much to do to have the region ready to answer to situations related to violence or other specific needs, such as the appropriate response to populations affected by disasters (natural or man-made) and the needs of vulnerable groups.

Countries in the region will be ready to answer to these situations when an appropriate range of mental health services, from promotion and prevention to rehabilitation and recovery, based in the community will be available and when mental health will fully be integrated with general health services.

When discussing violence and mental health, mental health professionals should be aware that most LACs’ mental health systems create and direct violence toward individuals with mental disorders and their families. Until changes occur to their mental health systems, this violence will continue to neglect to provide patients with the attention and services they need and will maintain the idea that the mentally ill are violent.

Integrating mental health with general health services is a good strategy to ensure that the health system as a whole will offer adequate care to the people who need it.

References

1. Murray, C. J. L. et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. 2010. Lancet, 2012; 380: 2197–2223.

2. Ferrari, A. J., Charlson, F. J., Norman, R. E., Patten, S. B., Freedman G., et al. 2013. Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age and year: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. PLoS Med 10(11): e1001547. doi: 10.1371/journal. pmed.1001547.

3. Kohn, R., Saxena, S., Levav, I., and Saraceno, B. 2004. The treatment gap in mental health care. Bull World Health Organ 82: 858-66 pmid: 15640922.

4. World Health Organization. World Mental Health Survey Consortium. 2004. Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAVA, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15173149.

5. Kohn, R. 2013. Treatment gap in the Americas, http://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_contentandview=articleandid=9408andItemid=99999.

6. World Health Organization. 2011. Mental Health ATLAS 2011, http://www.who.int/mental_health/publications/mental_health_atlas_2011/en.

7. Pan American Health Organization. 2013. WHO-AIMS: Report on mental health systems in Latin America and the Caribbean, http://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_contentandview=articleandid=935andItemid=1106andlang=enandlimitstart=7.

8. World Health Organization. Comprehensive mental health action plan 2013–2020, http://www.who.int/mental_health/publications/action_plan/en.

A.5

HEAVY EPISODIC ALCOHOL USE AND INTIMATE PARTNER VIOLENCE: A CROSS-CULTURAL PUBLIC HEALTH ISSUE

Cory A. Crane, Ph.D.

Kenneth E. Leonard, Ph.D.

Research Institute on Addictions

University at Buffalo

Intimate partner violence (IPV) involves the perpetration of physically aggressive acts against a spouse or dating partner and has been identified as a serious social concern with considerable health and financial costs at the individual, family, and societal levels (Lawrence et al., 2012). A review of 249 peer-reviewed articles detected a high prevalence of past year and lifetime (19.2 percent and 33.6 percent, respectively) physical IPV victimization among heterosexual individuals, with slightly higher rates of victimization among females (23.1 percent) than males (19.1 percent) across all studies (Desmarais et al., 2012). In a separate review of 111 articles, Desmarais and colleagues (2012) reported comparable rates of physical IPV perpetration across all participants (24.8 percent) with slightly higher rates of female-to-male (28.3 percent) than male-to-female (21.6 percent) perpetration.

Traditional conceptual models of IPV focused on constructs such as gender roles, power and control, and cultural sanctions for male-to-female aggression, and were advanced through a societal mandate to help explain and prevent IPV (Pence and Paymar, 1993). These early models spawned intervention approaches and public policies that focused on accountability as well as psychoeducation and remain predominant today (Babcock et al., 2004). Those who adhered to this early conceptual framework argued that alcohol use should be considered an unacceptable excuse for violent behavior and unequivocally rejected the notion that intoxication may play a causal role in episodes of IPV. The past 20 years of research, however, has largely failed to support both the traditional models (Dutton and Corvo, 2007) and associated interventions (Babcock et al., 2004), and has offered largely consistent empirical support for an alternative conceptualization of heavy alcohol use as a contributing causal factor in episodes of IPV (Leonard, 2005).

This research has been guided by and has contributed to the current prevailing theories describing the proximal effects of heavy alcohol consumption on violent behavior, which focus on attention allocation and the

disinhibiting characteristics of alcohol. These theories are based on the direct psychopharmacological effects of alcohol, which include a wide range of transitory impairments in higher-order executive cognitive functioning (Giancola et al., 2010). Among other effects, alcohol intoxication is thought to impair decision making through the exacerbation or amplification of attention to dominant environmental cues that may instigate violence while limiting attention to less salient cues that may inhibit violent responding, such as the long-term consequences of violent actions (Steele and Josephs, 1990; Taylor and Leonard, 1983). Alcohol expectancies serve as the basis for an alternative set of theories by which alcohol facilitates IPV through the perpetrator’s own beliefs about the mitigating effects of intoxication on one’s own culpability for socially unacceptable partner violent behavior. Although alcohol expectancy theories have received some scientific support, the majority of research has found little evidence for moderating effects on the relationship between alcohol intoxication and the perpetration of partner violence (e.g., Quigley and Leonard, 2006).