3

Factors Influencing Affordability

The affordability of prescription drugs in the United States is influenced by a complex and highly interactive set of factors. The factors that tend to increase the cost of drugs for patients include the following, each of which is discussed in turn in this chapter:

- High launch prices, with the price of the drug then often increasing over time.

- Inadequate competition when market exclusivity ends.

- The interaction of market power, health insurance, and the lack of effective incentives for controlling product price.

- Unequal bargaining power between buyers and sellers.

- Research, development, and marketing expenditures as well as other business expenses.

- Insurance benefit designs with significant patient cost-sharing provisions.

- Inadequate performance of patient assistance programs and other public programs intended to make medicines more affordable for patients.

- Lack of adequate information affecting choices regarding medicines.

PRODUCT PRICING

Patent law establishes the exclusive right for inventors to apply their work for a specified period of time, either through direct manufacturing or by licensing to others. During patent exclusivity, prices of products are typically

set higher that permit patent holders to realize greater profits than would be achievable in a competitive marketplace. Many observers of the biopharmaceutical sector characterize this pricing practice as “what the market will bear.” Others rationalize it as properly and necessarily rewarding the pursuit of a high-risk, capital-intensive endeavor. That is, producers can be expected to set prices that are constrained only by how much consumers are willing to pay for a product that is protected by exclusivity.

The entry of generic drugs into the market provides competing products that are generally sold at much lower prices than the original branded product. Although the original branded product may continue to be offered at a high price, typically the lower cost of the generic will lead a large number of consumers to choose it. In recent years, between 80 and 90 percent of all prescriptions in the United States have been filled with generic products (Boehm et al., 2013; GPhA, 2015; Lee et al., 2016). However, if there is insufficient competition among the generic alternatives themselves, the prices of a drug might not drop to the anticipated competitive level. This particular issue is explored in a later section of this report.

A parallel issue relates to the particular manner in which drugs are actually priced in the United States (as described in Chapter 2). Specifically, manufacturers and distributors of drugs start with list prices at the time of launch and often modify them over time. However, in many cases a product’s list price is immediately discounted by manufacturers and distributors in sales to pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), insurance companies, wholesalers, retailers, and others. Unfortunately, there are few publicly available data about the nature of these discounts, so it is impossible to determine exactly how net prices for consumers are derived. The situation is made more complex by the fact that the net price may differ greatly among different consumers.

Biopharmaceutical manufacturers often state that too much attention is focused on the list price of drug, as opposed to the end cost to health plans and patients. However, in a system with a broad use of rebates and discounts, list price matters because it is the starting point for all negotiations in the supply chain. As discussed earlier, it also matters because (1) uninsured patients pay list price at the pharmacy, and (2) cost sharing for insured patients is sometimes defined as a fraction of list price. The effects of high list prices are discussed in the following sections, with branded, generic, and other drug products covered separately.

Branded Drugs

Although branded medications make up approximately 10 percent of all prescriptions in the United States, they account for nearly three-quarters

of prescription drug spending (GPhA, 2015). Spending for all retail prescription drugs accelerated significantly in 2014 and 2015, before slowing in 2016 (QuintilesIMS, 2017a). The spending rate was 10.3 percent, which rose to 12.4 percent between 2014 and 2015 before falling to 5.8 percent in 2016—still twice the 2.5 percent rate of growth in 2013 (QuintilesIMS, 2015a, 2016a, 2017a).

The cost of branded drugs is influenced by their launch prices—the prices set by the manufacturer for the new drugs when they first become available on the market—and the subsequent annual increases in their list prices. Recent data on anti-cancer drugs show that on average launch prices increased by about $8,500 per year over the past 15 years (Howard et al., 2015). Other studies have found similar increases in the prices of cancer drugs after their launch (Bach, 2009; Bennette et al., 2016; Shih et al., 2017).

A 2009 report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) estimated that between 2000 and 2008, 416 brand-name drug products displayed “extraordinary” price increases (GAO, 2009). The 416 products represented 321 specific medications, with some medications being available in different drug strength and dosage forms; for example, the 416 products included eight different strength and dosage forms of the beta blocker Inderal. Most often the increases in price reported in the study were between 100 and 499 percent, but in a few cases, specifically for drugs used to treat such conditions as fungal or viral infections or heart disease, a drug’s price increased by 1,000 percent or more.

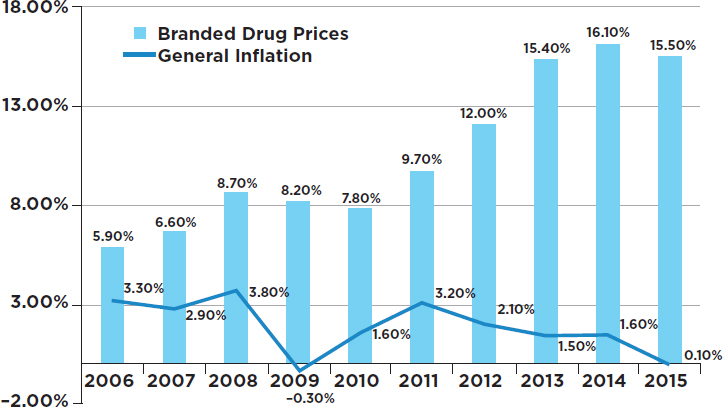

The absolute price increases for branded drugs ranged from $0.01 per unit to $5,400 per unit. The unit price of a drug is, of course, only one factor in determining the cost of a full course of treatment for a medical condition. The cost for a full course of treatment for one drug used to treat one rare form of cancer increased from $390 to more than $3,000 during the study period (GAO, 2009). Figure 3-1 shows how the prices of 268 top branded drugs rose throughout the period 2006–2015, with the yearly increases being consistently higher than the increases in the overall consumer price index—sometimes much higher.

Spending on specialty medicines has nearly doubled over the past 5 years, clearly outpacing the consumer price index and accounting for more than two-thirds of the overall growth in spending on medicines between 2010 and 2015 (AHIP, 2015; QuintilesIMS, 2016a). One result of this increase is that Medicare beneficiaries face rapidly growing out-of-pocket payments for specialty drugs. This trend is likely to continue as the population ages and more treatments become available for difficult-to-manage diseases (Dusetzina and Keating, 2015; Dusetzina et al., 2017; Trish et al., 2016). On the challenge of how to go about financing very expensive

SOURCE: Schondelmeyer and Purvis, 2016.

branded drugs, see Box 3-1. Whether existing or new drug therapies are actually effective in patients is another issue that must be considered.1

Generic Drugs

Once branded medications lose their patent exclusivity, generic versions can enter the market with approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Generic drugs are the same as the branded “innovator” drugs in terms of dosage, safety, strength, chemical composition, route of administration, quality, performance characteristics, and intended use (FDA, 2017a). When a generic enters the market, it tends to be priced more closely to the marginal cost of production, which often pressures the company that manufacturers the branded drug to lower the cost of that drug in

___________________

1 Many therapies benefit only some of the patients who receive them. In recent years improved diagnostic tests have become particularly valuable, especially in oncology, for providing insights, based on an individual’s genomic makeup and other biomarkers of his or her disease, into whether a particular therapy is likely to be of benefit (NASEM, 2016). Three issues may emerge in the future regarding these predictive diagnostics. The first issue involves the incentives of third-party payers to adequately compensate for diagnostics, which are often far more expensive to develop and apply than traditional laboratory tests. The second issue may arise from the increased use of companion diagnostics for rare diseases that affect only subpopulations. Third, as diagnostics advance the goal of precision medicine, the logical result will be that a given drug is prescribed for fewer patients.

order to remain competitive (Berndt and Aitken, 2011; Frank, 2007; GPhA, 2015; Grabowski et al., 2014; Greene et al., 2016; QuintilesIMS, 2016b).

People in the United States commonly pay lower prices for generic drugs than do people of other countries (Wouters et al., 2017). Generic drugs now account for up to 90 percent of all prescriptions written in the United States (GPhA, 2015; Grabowski et al., 2016). By comparison, in the early 1980s generics accounted for less than 20 percent of all prescriptions written and many profitable branded drugs with expired patents still did not have generic competitors (Frank, 2007). Analyses show that when generic drugs enter the market, they reduce the market share of the related brand drugs (Grabowski et al., 2014). If only a single generic producer enters the market, it does not necessarily reduce prices. Typically, once a drug has reached the end of its exclusivity period, the price of the branded drug may remain about the same during the period of exclusivity, or it may even drift upward, but as the generic prices decline, they capture a major portion of the market. It may take several competing generic companies to enter the market before the prices for the drug to reach their lowest possible level based primarily on cost of production.2 Generic prices, not surprisingly, exhibit the largest reductions in markets where revenues are initially above average (Gupta et al., 2016; Olson and Wendling, 2013). Multiple producers of generic drugs also help prevent shortages should one firm ceases production. From the standpoint of ensuring ongoing production and competition in the market, mergers between competing firms that make identical or biosimilar products—either generic entrants or the original branded manufacturer—are not a desirable occurrence. The Federal Trade Commission has regularly challenged such mergers (FTC, 2017).

Two recent studies examined manufacturer entry, exit, competition, and the relationships among generic drug supply structures and inflation-adjusted prices. The first of these studies found that the median and the mean number of manufacturers was about two and four, respectively, and that the number of suppliers has been declining in recent years, due both to more exit and less entry of manufacturers (Berndt et al., 2017b). The second found that a very large portion of generic manufacturers have small portfolios consisting of less than five products, while a small number of generic manufacturers have very large portfolios with hundreds or even thousands of products (Berndt et al., 2017a). Approximately 40 percent of product markets were supplied by only a single manufacturer. The share supplied by one or two manufacturers increased over time and was larger

___________________

2 The current backlog of unapproved generics at the FDA is a hurdle to generics pushing the costs of branded products down. Although the FDA’s review times for generic drug applications have decreased since the implementation of the Generic Drug User Fee Amendment, there were 2,640 generic drug applications pending approval as of April 1, 2017 (FDA, 2017f).

among non-oral drugs but varied across therapeutic classes. Generic drug prices also increased over time, particularly after 2010, following the implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) and the Generic Drug User Fee Amendments. The authors concluded that generic drug markets in the United States typically involve small-revenue products and are increasingly tending toward duopoly or monopoly supply. Taken together, these findings suggest that the conventional wisdom involving generic drugs in the United States—that competition among generic manufacturers, facilitated by buying power consolidation among insurers and other purchasers, results in increasing access to safe and effective treatments for chronic disease, offsetting at least to some extent the higher prices of newly launched and existing branded drugs (Aitken et al., 2016; Duggan et al., 2008)—may be less true now than previous studies suggested.

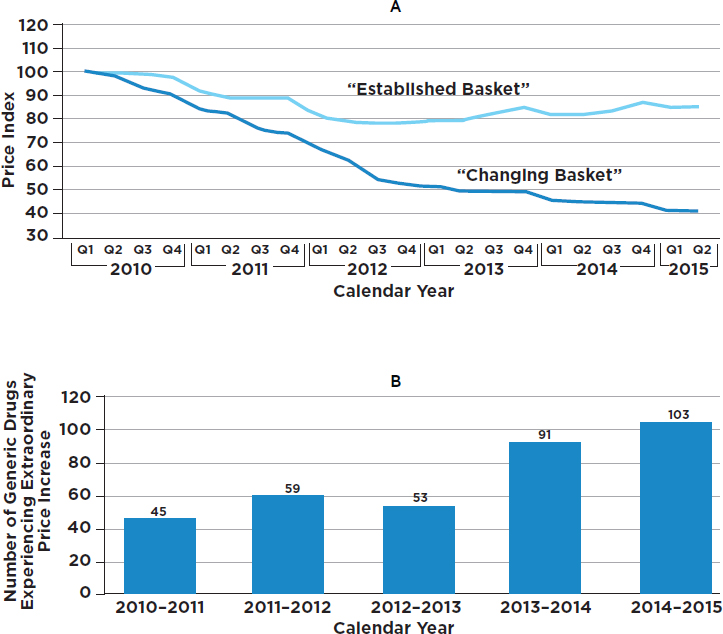

Abrupt price increases have been a matter of concern for generics as well. When the GAO examined the price histories of 1,400 generic drugs, it found 351 cases of extraordinary price increases within a single year (GAO, 2016b) (see Figure 3-2). For example, the cost of a generic antidepressant used to treat the symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder increased by more than 2,000 percent in 1 year, jumping from $0.34 per capsule in the first quarter of 2013 to $8.43 per capsule in the first quarter of 2014. Also, the price of a generic nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug that can be used to treat rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis increased by more than 2,000 percent, from $0.09 per capsule in first quarter 2010 to $1.94 per capsule in the first quarter of 2011 (GAO, 2016b). In some cases the prices of generics increased because of limited competition, while in other cases it was a result of delays in the review process by the FDA (GAO, 2016b; Greene et al., 2016). The lack of therapeutically equivalent drugs in the market limits competition and may contribute to extraordinary price increases (GAO, 2009). These issues further highlight the importance of having multiple producers of generic drugs. However, a recent lawsuit brought by the attorneys general of 45 states and the District of Columbia accused 18 companies and subsidiaries of colluding to fix prices for 15 medicines (Friefeld, 2017).

Biosimilars

A biosimilar is a biological product that contains a version of the active substance of an FDA-approved “reference” product (FDA, 2017b). The first biosimilar, a relative of somatropin (a growth hormone), was approved by the European Medicines Agency in 2006 (Simoens, 2011). Since then, 28 biosimilar products have been approved in Europe (QuintilesIMS, 2017b). Estimates of the overall cost saving that the European Union will experience

NOTES: “For the changing basket of all generic drugs, the number of drugs included in each period varies from 1,733 to 2,124. For example, the period going from the first quarter of 2010 to the second quarter of 2010 has 1,733 drugs. A total of 2,378 unique drugs were included across our study period. To be considered an established drug, a drug had to be in the Medicare Part D claims data for each quarter from the first quarter of 2009 through the second quarter of 2015 and meet certain other data reliability standards. A total of 1,441 drugs met these criteria. Due to data availability at the time we conducted our study, the second quarter of our 2015 Medicare Part D claims data is limited to data from April and May” (GAO, 2016b, p. 11).

SOURCE: GAO, 2016b, Figures 2 and 3.

by 2020 from using biosimilars range from €11.8 billion to €33.4 billion (Haustein et al., 2012).

In the United States, however, biosimilars have not yet become a major part of the drug market. There are currently only five approved biosimilars in the United States, although there are more than 60 currently under development. The first biosimilar was approved by the FDA in 2015, a version of the leukocyte growth factor filgrastim (Neupogen); this was followed by three more approvals in 2016 and one thus far in 2017. In 2009 the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) created an abbreviated licensure pathway (351(k)) for products that are shown to be biosimilar to, or interchangeable with, a previously approved reference product.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated that the BPCIA would result in a total cost reduction of $25 billion from 2009 to 2018. Savings to the U.S. government were projected to be $5.9 billion (CBO, 2008). An analysis by the RAND Corporation estimated that the use of biosimilar products across all therapeutic classes would result in savings between 2014 and 2024 of from $13 billion to $66 billion, depending on the amount of competition, with a best estimate of $44.2 billion (Mulcahy et al., 2014b). Among the deterrents to those wishing to bring biosimilars to market are uncertainty regarding regulatory requirements and also uncertainty about patent procedures (Hakim and Ross, 2017; Wong et al., 2017).

PRICE REGULATION

The patent law and health insurance systems in the United States are in concept similar to those in other developed countries. The United States, however, differs from most other nations with respect to the ability of the government to limit the prices of prescription drugs charged by manufacturers. While most other developed nations have governmental mechanisms for negotiating or controlling prescription drug prices, either directly or de facto (WHO, 2015), there is no nationwide regulation of drug pricing in the United States.

Table 3-1 summarizes the relevant pricing mechanisms used in five other developed nations with economies and legal structures similar to those in the United States. The tools employed in these countries include evaluating drugs using cost-effectiveness criteria and other related methods, imposing pricing limits or negotiations, and using formularies (including lists of “essential drugs,” as are discussed in Box 3-2).

TABLE 3-1

Approaches to Drug Pricing in Other Countries

| National Organization | Australia | Canada | Germany | India | United Kingdom | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee | Patented Medicine Prices Review Board | Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health | Federal Joint Committee or the Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care | National Pharmaceutical Pricing Authority | National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence | |

| Applicability | Public payers | All payers | Public payers except in Quebec (non-cancer drugs) | All insurers | All payers | National Health Service |

| Review Criteria | Comparative effectiveness, safety, and cost-effectiveness; projected usage and overall costs to the health care system | Therapeutic innovation; comparative pricing with respect to France, Germany, Italy, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States | Comparative effectiveness, safety, and cost-effectiveness; patient experiences | Comparative benefit | National List of Essential Medicines prepared on the basis of efficacy, safety, cost-effectiveness, and common diseases | Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness |

| Decision | Coverage (yes, no, limited) | Price reductions or rebates | Coverage | Price setting after first year on the market | Formulary inclusion or exclusion | Coverage |

| Binding | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

SOURCE: Adapted and expanded from Kesselheim et al., 2016.

Australia

The Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) was established as part of the Australian government’s broader National Medicines Policy in order to guarantee public access to (subsidized) essential medicine (PBS, 2017a). The PBS provides a list of drugs approved for coverage. To have a drug listed, its manufacturer must file an application with the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC), an independent body appointed by the Australian government that decides which medicines are approved and which are not (PBS, 2017b). Only those drugs on the PBS list are subsi-

dized by the Australian government. The PBAC regularly updates the list to include prescribing restrictions, maximum quantities, and price. When deciding whether to list a medicine on the PBS, the PBAC assesses the national disease burden, the medicine’s clinical effectiveness, its safety, and cost-effectiveness compared with alternative treatments. Australia uses reference pricing3 for generics and for groups of drugs with similar health and safety that can be used interchangeably. The maximum reimbursement for a medicine in a therapeutic group is based on the level of the lowest price in the approved group, and patients pay any difference between the price of the drug purchased and the reference price (Paris and Belloni, 2014).

Canada

The prices of medicines in Canada are determined by a combination of federal regulations and provincial negotiations. The price of every patented drug sold in Canada, both prescription and non-prescription, is regulated federally through the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB, 2017a).4 The PMPRB performs an initial review of a new drug’s price to determine if it is comparable to other products already sold in Canada. If the drug is comparable to an existing product, the price is not allowed to be greater than that of the existing drug. However, if it is not comparable, the price is allowed to be set at a point not greater than the median price in seven other industrialized countries: France, Germany, Italy, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Further increases in drug prices are limited to the growth in the consumer price index (PMPRB, 2017b).

Germany

In Germany, the Act for Restructuring the Pharmaceutical Market in Statutory Health Insurance (AMNOG) established a mandatory benefit assessment of prescription drugs distributed in that country. The subsequent price negotiation process for new medicines is required to be completed within 1 year of product launch (Ruof et al., 2014). Under AMNOG, pharmaceutical companies can independently set the initial list price when they bring a new drug to market; however, they must submit a cost–benefit dossier in order for the drug to be fully reimbursed by all German insur-

___________________

3 Reference pricing involves judging the therapeutic effectiveness of drugs within a disease group and reimbursing based on the least expensive option offering comparable effectiveness.

4 The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, in comparison, is responsible for making recommendations to inform coverage decisions of public drug schemes managed at the federal or the provincial level—except for Québec.

ance plans for the first 12 months. During that period, the Federal Joint Committee—the highest nongovernmental decision-making body of clinicians, hospitals, and health insurance funds in Germany—commissions a clinical comparative effectiveness review by the Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care, a nongovernmental research body. Within 6 months of a drug’s introduction into the market, the Federal Joint Committee, after receiving the results of the review from the Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care, will determine the new drug’s added benefits, if any, over existing drugs or treatments. The review criteria include benefits and risks for specific patient subpopulations. Each drug is given a final rating between 1 and 6, where 1 denotes “extensive benefit” and 6 means “less benefit” than an existing drug. A drug can receive different rankings for different patient subpopulations. Based on these ratings, the company then enters negotiations with the National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Funds to set the reimbursement price. One year after market launch, this reimbursement price replaces the initial list price of the drug.

Drug companies in Germany can choose to sell their products at higher prices; however, patients who want a newer, lower-ranked drug must pay the difference between the market price and the government’s set reference price. Importantly, if a drug company charges an excessive rate for a lower-ranked drug in the first year of availability, the excess revenues must be returned to payers. A drug company can opt for a drug to not be assessed, in which case the drug’s price is set through the German reference pricing system. Under the reference pricing system, the price is based on that of other drugs in the same therapeutic class, including lower-priced generic alternatives. Germany conducts more rigorous appraisals of new drugs than most other countries (Fischer et al., 2016) and has achieved significant savings in new drug spending. In 2015 Germany reported a savings of about $1 billion on new drug spending (Lauterbach et al., 2016).

India

In India, a major transition economy, the National Pharmaceutical Pricing Authority has the task of monitoring drug prices (India Department of Pharmaceuticals, 2017). By law, the authority fixes the maximum prices of items included in India’s National List of Essential Medicines. Under current regulation, manufacturers are allowed to increase prices up to 10 percent annually for medicines that are not included in the national formulary. The pricing authority also recovers overcharge amounts from manufacturers of controlled drugs; monitors drug shortages and the prices of decontrolled drugs in order to keep them at reasonable levels; and collects data on individual companies’ exports and imports, production, profitability, and market share of bulk drugs and formulations. India’s National

List of Essential Medicines is based on efficacy, safety, cost-effectiveness, and common diseases of public concern in India (WHO, 2017b).

United Kingdom

The Pharmaceutical Price Regulation Scheme, which governs drug pricing in the United Kingdom, is a voluntary arrangement between the governments of the United Kingdom and Northern Ireland and the branded pharmaceutical industry, as represented by the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry, 2017). Under this regulatory scheme, which has existed in various forms since 1957, pharmaceutical prices are not directly regulated; however, if a company exceeds the profit threshold set by the government, it is given an opportunity to justify its profits and adjust the thresholds.

If the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (established in 1999 to provide guidance on the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of interventions and pharmaceuticals compared with current standard practice) does not consider a new medicine to be cost-effective, it does not recommend it for use by the National Health Service (Trowman et al., 2011).

RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT COSTS

Estimates of the research and development costs of a new drug vary widely (Morgan et al., 2011). Decisions regarding investments in biopharmaceutical research and development depend largely on drug manufacturers’ assessment of future revenues. The greater the expected revenue from a prospective new drug, the more a drug maker will be inclined to develop it (GAO, 2009).

Spending on biopharmaceutical research and development has increased steadily over time (as addressed in the next section of this report). Revenues from the sales of prescription drugs must eventually pay for most of the costs of research and development, among other expenses, and a rise in research and development expenses will generally contribute to rising drug prices. The increase in research and development costs over time is attributable to several factors, particularly the extensiveness and cost of clinical trials, although it has been noted that the future may bring some opportunities for reducing such costs (Laurer et al., 2013).

A 2011 systematic analysis found that estimates of the cost of developing a single drug ranged from $161 million to $1.8 billion (Morgan et al., 2011). A 2016 analysis reported that the estimated cost to bring a new drug successfully to market is around $2.6 billion, with post-approval costs increasing the total to approximately $2.87 billion (DiMasi et al.,

2016). These figures are frequently cited by drug manufacturers in public and in policy discussions. A more recent analysis that considered 10 cancer drugs produced by 10 companies reported that the cost of developing a cancer drug was in the range of $157 million to $1.95 billion, with the median costs substantially lower—around $648 million, with the inclusion of opportunity costs bringing the total to $757 million (Prasad and Mailankody, 2017).

However, questions abound regarding the reliability of these studies and their estimates (Avorn, 2015; Goozner, 2017; KEI, 2014; Pitts, 2017; Wells, 2017). The basis of much of the information considered in the analyses of DiMasi and colleagues is undisclosed, and most studies have not been replicated, which raises concerns about the meaningfulness and validity of the estimates. The analysis supporting the more recent estimate from Prasad and Mailankody has been criticized for poor selection criteria. For example, critics note that their study underestimates the degree of failure in drug development by excluding larger biopharmaceutical companies that had a high percentage of cancer drug failures.

On occasion the total cost of drug development has been estimated using aggregate data on annual research and development costs reported by biopharmaceutical companies compared with the annual number of drugs approved by the FDA. Several challenges arise when using these highly aggregated data. For example, companies may conduct research and development that is not specifically related to developing novel drugs. Companies may also invest in product improvements, including the reformulation of existing drugs, as well as in analyses of the side effects of drugs already on the market. One advantage of such calculations is that they will generally take into account the large sums of money that drug companies invest in research and development on products that never reach the market. These are real costs that must be taken into account when calculating the costs of developing those products that are successful, and, indeed, publicly traded firms themselves must recognize these costs in portraying their overall financial status and also in pricing their products.

The research and development costs related to new molecular entities need to be separated from those devoted to products licensed from other firms. In the latter instance, the relevant research and development costs are reflected on the books of the licensor. Furthermore, estimates of the cost of capital that are reported in aggregated data generally do not account for the tax advantages of research and development expenditures (Riggs, 2004). In 1993, the Congressional Office of Technology Assessment estimated that the cost of research on a single drug through new drug approval was about $194 million in 1990 dollars ($363 million in 2017 dollars). The study used a marginal corporate tax rate of 34 percent, which reduced the actual cost of qualifying research and development (OTA, 1993).

The costs of abbreviated new drug applications (ANDAs) for generics have also been estimated. For oral tablets and capsules, the direct costs of ANDA applications are modest ($1 million to $5 million) compared with potential profitability (Berndt and Newhouse, 2012). Not much is known about the direct costs of obtaining ANDA approvals for infused or injected drugs.

In summary, the costs of research and development for biopharmaceutical development appear to have steadily increased in real terms over time, although it is difficult to know by exactly how much because estimates vary widely according to the analytical approach and the data sources used in making them. In a market-oriented economy, these increases in research and development costs would, over time, be expected to contribute to rising prescription drug prices.

PRODUCT PROMOTION AND DISTRIBUTION

Drug manufacturers have a direct interest in the choices made by patients and clinicians, and they have various ways to influence these choices. These include

- Discounts to PBMs and wholesalers: Manufacturers commonly sell their products at discounted prices, most importantly through the system of PBMs that is now firmly established as part of the U.S. biopharmaceutical supply chain. In concept these discounts are passed through (at least in part) from the PBMs to the consumer via the consumer’s prescription drug insurance plans—primarily through the choices of prescription drug tier and the differing copayments often associated with each drug. Greater discounts would generally be expected to lead to lower consumer copayments at the end of the supply chain. However, it is not clear that this occurs in practice.

- Marketing of products: Marketing by biopharmaceutical companies contributes to higher prescription drug expenditures through two avenues. First, studies indicate that marketing increases prescription drug use (Alpert et al., 2015; Donohue et al., 2007). Second, the costs of marketing are part of the overall cost structure of drug manufacturers and thereby place upward pressure on prices.

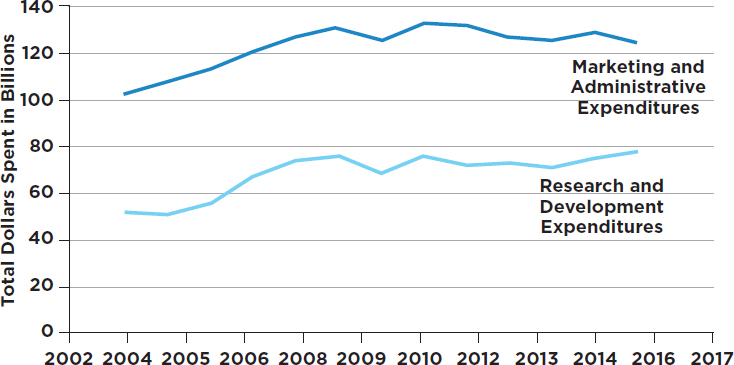

The exact amount that the biopharmaceutical industry spends on product promotion remains undisclosed and thus must be inferred, to the extent possible, through secondary sources of information. A recent analysis of annual financial reports and Securities and Exchange

Commission (SEC) filings of 12 large pharmaceutical companies found that between 2003 and 2015 expenditures on marketing and administration5 (a figure that includes executive pay) increased noticeably and exceeded research and development investments by up to 80 percent. Figure 3-3 displays one estimate of marketing expenditures and research and development expenditures over time.

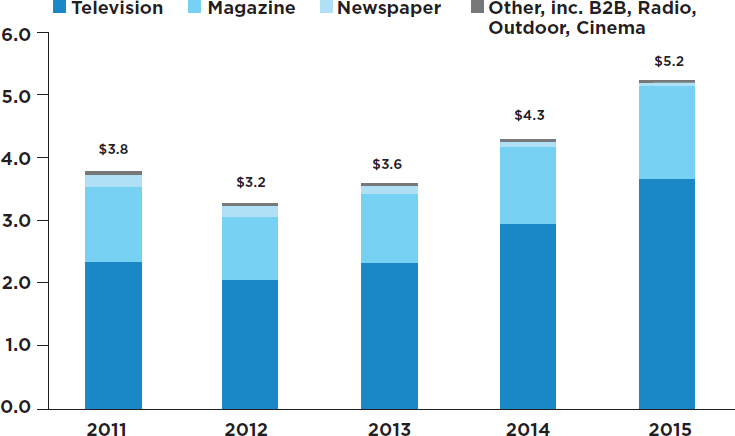

- Direct-to-consumer advertising of pharmaceutical products: A more recent practice by pharmaceutical companies, direct-to-consumer advertising, has attracted considerable attention among those concerned with the objectivity of the process of prescribing drugs. It is noteworthy that among developed nations, the marketing of prescription drugs through direct-to-consumer advertising is legal only in the United States and New Zealand (Mackey and Liang, 2013). In recent years, direct-to-consumer advertising in the United States has grown rapidly (Wilkes et al., 2000). The Internal Revenue Code makes direct-to-consumer advertising tax deductible as a business expense, as is the case for most advertising in other industries. Recent estimates indicate that in 2016, spending on direct-to-consumer advertising was about $5.2 billion, the bulk of which was used for television promotions (Robins, 2016) (see Figure 3-4). These estimates, as compiled by Nielsen, exclude spending on Facebook, Twitter, and other digital media.

The steady growth in such advertising places increasing demands on clinicians to accommodate patient requests for advertised products that may be more costly than other treatment options (or, alternatively, to expend time explaining why an advertised medication might not be the best option for the patient). This in turn adds to the ultimate cost of drug treatment. A recent analysis of direct-to-consumer advertising concluded that these marketing efforts increased drug take-up and use—with 70 percent of the increased use arising from new patients—but also increased adherence to prescription plans (Alpert et al., 2015).

Some studies have found that direct-to-consumer advertising can increase patients’ knowledge about treatment options and may enhance the clinician–patient relationship, while others have identified effects that tend to offset these potential benefits (Lexchin, 2017; Mailankody and Prasad, 2017; Wilkes et al., 2000). In short, direct-to-consumer advertising has the potential to educate patients about conditions and their potential treatments; however, the practice may also result in unjustified demands

___________________

5 SEC filings (10-K forms) show only a blend of marketing and administration costs, thus making it difficult to isolate marketing costs as a separate item.

SOURCE: Data retrieved from Belk, 2017. See http://truecostofhealthcare.org/pharmaceutical_financial_index (accessed November 15, 2017).

NOTE: Digital outlets not included.

SOURCES: Natalia Broshtein/STAT, from Robbins, 2016; data from Nielsen.

for expensive branded medications. The conversations triggered by this advertising may increase the pressure of clinician–patient conversations, which are already affected by short visit times, and one result may be overprescribing.

Studies of the effect of advertising on prescribing practices have shown that such advertising increases sales, reduces the underuse of some medicines needed to treat chronic conditions, and leads to some overuse of prescription drugs (Donohue et al., 2007). A randomized controlled trial to study the influence of patients’ requests for direct-to-consumer advertised antidepressants found that patients’ requests had a material effect on clinician prescribing practices for major depression and adjustment disorder (Kravitz et al., 2005). A Canadian report showed that in recent years a significant amount of money has gone toward drugs that offered “little to no therapeutic gain. This result calls into question whether doctors read journal advertisements or see sales representatives to acquire information about important medical therapies” (Lexchin, 2017, p. E724).

For more than a century there have been efforts in the United States—including legislation, regulations, and advocacy—to control the marketing and advertising of pharmaceuticals directly to consumers (Mogull, 2008). Recently, the American Medical Association called for a complete ban on direct-to-consumer advertising, arguing that the “growing proliferation of ads is driving demand for expensive treatments despite the clinical effectiveness of less costly alternatives” (AMA, 2015). The Congressional Budget Office (2011) examined the potential effects of a moratorium on direct-to-consumer advertising of new prescription drugs and concluded that:

- Drug manufacturers would probably expand their marketing to clinicians to substitute for at least some of the banned advertising to consumers.

- The number of prescriptions filled would probably decrease for some drugs, but for other drugs the number of prescriptions might be little changed, owing both to the likely substitution of other types of promotions and to other factors that influence a drug’s reach in the prescription drug market.

- Any change in prescription drug prices would depend on changes in demand; however, prices for new brand drugs that normally would be part of a direct-to-consumer advertising campaign could increase, since sales would be reduced.

- A moratorium could affect public health. The exact result would depend on whether the benefits of fewer unexpected adverse health events were greater than the health costs of possibly reduced use of new and effective drugs.

While the results of studies of the effects of direct-to-consumer advertising are somewhat inconclusive or at least mixed, drug advertisements remain pervasive and influence the manner in which clinicians prescribe. Because advertising is demonstrably effective in stimulating consumer demand for branded drugs and adds to the cost of doing business, such direct-to-consumer advertising likely contributes to the nation’s high prescription drug costs.

The FDA regulates the content of this advertising, seeking to ensure a fair balance in describing benefits and risks and making certain that the risks are included in a prominent statement (Ventola, 2011). Although proposals exist to ban direct-to-consumer advertising of drugs, the constitutional protection of free speech in the United States may constrain such efforts.6 The U.S. Supreme Court has regularly ruled that commercial speech is protected by the First Amendment.

Marketing practices such as direct-to-consumer advertising aside, there are several other ways that manufacturers influence the debates and discussions in the biopharmaceutical sector, some of which are described in Box 3-3.

- Direct rebates to consumers: Another mechanism used by pharmaceutical manufacturers to affect the choices of patients and prescribers is the provision of direct payments to patients upon proof that they are actually using the specific drug. These payments have two key features. First, they almost universally are

___________________

6 An often compared scenario is the federal legislation that banned advertising of tobacco on television and radio beginning in 1971. In 1967, the Federal Communications Commission ruled that the “fairness doctrine” be applied to cigarette advertising, which meant that television stations that broadcasted tobacco advertisements were required to give equal time to showing anti-smoking messages, during prime time as well as during children’s programs, leading up to the Public Health Cigarette Smoking Act of 1969, which banned cigarette advertisements on American radio and television.

After the ban, the tobacco industry increased advertising in other media, but the total volume of advertising by the industry decreased. In parallel, broadcast media no longer were compelled to run anti-smoking messages, and their removal may have contributed at least briefly to increase smoking rates. The anti-smoking advertisements were mandated by the Federal Communications Commission in response to the strong evidence of harm caused by tobacco, a unique situation.

The ban also appears to have reduced competition in the industry, allowing the firms selling cigarettes prior to the ban (the incumbent firms) to maintain higher prices than they would have if they had been challenged by market entrants. Without the ban, market entrants might have attracted consumers away from the incumbent firms using television and radio advertising. The financial advantage to incumbent firms may explain why the tobacco industry did not challenge the advertising bans (Eckard, 1991). The reduced cost of advertising may also have increased tobacco industry profits, a situation that might be repeated in the biopharmaceutical sector.

employed by makers of on-patent drugs—often in situations where competition exists from either generic or other branded drugs. Second, they are generally directed at patients with prescription drug insurance plans, using such language as “if you need help with your copayments.” Such rebates have the effect of counteracting higher-tier (larger) copayments set by PBMs and health insurance plans, thereby increasing annual insurance premiums for all enrollees in prescription drug plans but reducing the drug cost to the individuals receiving the rebate. A comparison of Figures 2-5

and 2-6 illustrates these mechanisms. One recent analysis estimated that copay coupons increase branded drug sales by 60 percent or more, almost entirely by reducing the sales of generic competitors, and that branded drug manufacturers receive a return of between four-to-one and six-to-one on every dollar spent on copay coupons (Dafny et al., 2016a). Analyses have also concluded that copay coupons increase costs for all enrollees in prescription drug insurance plans (Dafny et al., 2016a; Ross and Kesselheim, 2013).

IMPORTATION OF MEDICINES

One strategy that has long been advocated as a way of reducing prescription drug prices and countering drug shortages (see the section on drug shortages) in the United States is to import prescription drugs—especially generics and biosimilars—from other countries. The rationale is that importing lower-cost drugs from other countries with high-quality production systems (and, potentially, government limits on price increases) would cause U.S. manufacturers to be faced with greater competition and encourage them to reduce prices.

A related strategy is “reimportation,” or having U.S. wholesalers and pharmacies import and sell branded drugs that were produced in the United States but sold in other countries where prices are lower, as long as the FDA has approved a version of the same drug for domestic use.7 Essentially, the goal of reimportation is to negate drug manufacturers’ differential pricing across countries—and, in particular, the pattern of charging more in the United States than in other countries for the same drug (Outterson 2005). Such programs could in principle also be established by state or local governments.

The importing and the reimporting of prescription drugs have been perennial proposals in the U.S. Congress over the past two decades. A number of states and localities have experimented with pilot programs, which have generally encountered legal challenges. Despite the longstanding interest, efforts to legalize the practice have not been successful.

The Food, Drug, and Cosmetics Act (FDCA) prohibits the importation of prescription drugs made in the United States by anyone other than the manufacturer—with the exception of drugs approved by the secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) for emergency care. Another legal obstacle is that it is nearly impossible for drugs made for non-U.S. markets to satisfy the FDCA’s requirements relating to drug approval and labeling (CRS, 2008; Terry, 2004).

Importation and reimportation run the risk of enforcement actions for introducing “misbranded” drugs into U.S. markets. The federal Controlled Substances Act also bears on reimportation in that it prohibits the unlawful distribution of prescription drugs, such as narcotics and opioids, that meet the statutory criteria for controlled substances (CRS, 2008).

In 2000, Congress passed the Medicine Equity and Drug Safety Act

___________________

7 “Personal reimportation” proposals focus on making it easier for individual U.S. consumers to buy and import drugs from other countries. Personal reimportation is not permitted by law, but the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has historically exercised its discretion not to enforce this prohibition against individuals bringing medications into the United States for personal use (Reichertz and Friend, 2000). This report’s focus is on broader-scale reimportation proposals, which have greater potential for population-level impact.

that authorized the FDA to allow the reimportation of prescription drugs from a specified group of countries. The U.S. Congress again authorized reimportation in the Medicare Modernization Act, this time narrowing the list of acceptable countries to Canada. But neither act was implemented, due to opposition by the HHS secretary. Both statutes required the secretary to certify that reimported drugs would be safe and would significantly reduce costs. No secretary has yet been prepared to do so. Thus, importation and reimportation remain prohibited. Several subsequent legislative proposals have failed to clear these and other obstacles (Bluth, 2017).

Historically, the FDA has opposed reimportation out of concerns about its ability to ensure a safe drug supply (Bhosle and Balkrishnan, 2007; Terry, 2004). Although reimportation discussions often assume that the drugs would be imported from Canada, if a sufficient supply could not be obtained there it could become necessary to import from countries with a less robust record of preventing counterfeit, contaminated, expired, and mislabeled drugs from reaching the market. Moreover, drugs may be falsely labeled as originating in the United States or a Canadian pharmacy (Bhosle and Balkrishnan, 2007). FDA commissioners have consistently expressed skepticism about the agency’s ability, with its current financial and technological resources, to ensure the safety and authenticity of a much larger volume of imported drugs (Bhosle and Balkrishnan, 2007). Others note, however, a lack of evidence that Canadian drugs are less safe or that concerns about adulteration and other problems are unique to imported drugs (Kamath and McKibbin, 2003; Outterson, 2005). The proponents of importation have argued for further pilot studies of controlled importation systems, noting that the reimportation ban values drug safety absolutely, at the expense of financial access, and arguing that safety concerns have been overstated.

Even if importation or reimportation, or both, were allowed, it is not clear how much they would reduce drug costs for U.S. consumers. The outcome would depend largely on (1) the countries from which drugs may be imported or reimported, and (2) the strategic responses of U.S. drug manufacturers. The CBO (2003) has estimated that allowing reimportation from 25 countries would save $40 billion over 10 years; however, other research has concluded that the savings would be considerably smaller, about $1.7 billion annually (Danzon et al., 2011).

A key question is how large a supply of drugs Canada and other approved countries would make available for export back to the United States (or, in the case of generics, allow them to be imported by the United States at lower prices). The CBO has concluded that the savings would not be substantial if reimportation were limited to Canada because drug companies probably would not increase their Canadian sales enough to allow a significant propor-

tion of American-made drugs to be reimported from Canada (Kaiser Health News, 2009).

It is also possible that manufacturers could penalize countries and firms that exported products back to the United States or that imported generics and biosimilars to the U.S. market. Firms could, for example, raise the prices of drugs sold in Canada, or penalize wholesalers that reimported drugs by raising the prices of the drugs they sell to those particular wholesalers in the United States. There is anecdotal evidence of penalizing behavior on the part of U.S. manufacturers: in 2004, GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer announced that they would limit sales of their drugs to Canadian pharmacies that resold them to individual U.S. consumers (CRS, 2008). A larger question is whether importation and reimportation would spur manufacturers to reduce their investment in research and development.

DRUG SHORTAGES

In recent years there have been numerous high-profile reports of inadequate supplies of generic drugs that have served as the standard of care for some diseases. For example, shortages have been reported for two critical cancer drugs, Doxil and Methotrexate, a medication used as backbone therapy to treat pediatric cancer (Harris, 2012); various antibiotics, including doxycycline (Stone, 2015); and saline bags, which are used throughout inpatient and outpatient treatment (McGinley, 2017).

Although the number of new drug shortages has declined since 2011, prominent shortages exist among generic injectables and other drugs for cancer and cardiovascular conditions (ASHP, 2017a; GAO, 2014, 2016a), and drug shortages have been known to lead to adverse events and even increased patient morbidity and mortality (Duke et al., 2011; Gu et al., 2011; Kaakeh et al., 2011; Kaiser, 2011; McKenna, 2011). The more constrained supply of such drugs has also led to higher prices for these drugs (GAO, 2014; IOM, 2013).

Shortages, threatened and actual, often result from lapses in manufacturing quality (Fox et al., 2014; GAO, 2016a; Stomberg, 2016). For example, the immediate precipitating factors behind the shortages reported since 2009 (largely for infused and injectable drugs) include a lack of high-quality manufacturing processes and facilities and a lack of necessary compounds and raw materials (GAO, 2014; Pew, 2017; Stomberg, 2016; Woodcock and Wosinska, 2013). The lapses in manufacturing quality and the shortages in the of necessary or adequately manufactured raw materials that can lead to supply interruptions of certain drugs and other products regulated by the FDA are not new, but appear to be more frequently reported in recent years. For example, in 2008, the FDA reported that at least 81 deaths and 785 serious injuries were thought to be linked to a

raw heparin ingredient imported from China (FDA, 2012). This led to the withdrawal of the product from the U.S. market for a period of time and consequently there was an inadequate supply to meet American demand.

Yet, according to a recent report from the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, the immediate causes for more than one-half of drug shortages reported in 2016 were unknown (ASHP, 2017b). In some circumstances, unexpected consumer demand or an outbreak of a rare illness can contribute to drug shortages (ASPE, 2011; Fox et al., 2009; GAO, 2014; IOM, 2013; Pew, 2017). In addition, a federal report noted that class-wide shortages in 2011 were likely due to a rapid and sizeable increase in the scope and volume of products produced without a corresponding increase in overall manufacturing capacity (ASPE, 2011). The constrained supply of these drugs and the high costs of entry for manufacturers willing and able to produce these molecules for sale in the U.S. market also contribute to threatened and actual drug shortages (ASPE, 2011; Berndt et al., 2017a,b; Fox et al., 2009; IOM, 2013). The FDA response to periodic drug shortages has largely been to either pull or push more manufacturers into supplying U.S. demand for these products.

The growing trend to outsource drug manufacturing and to source base ingredients from non-U.S.-based manufacturing facilities, along with the highly publicized incident of adulterated heparin manufactured in China that evaded inspection by a resource-constrained FDA (U.S. Congress, 2008), led to key aspects of the Generic Drug User Fee Amendment (GDUFA), first enacted in 2012 (Conti and Berndt, 2017a). Specifically, GDUFA funded the FDA’s redesign of its inspection program and the associated user fee schedule to meet these new challenges.

More recently, under the Safety and Innovation Act of 2012, the FDA required drug manufacturers to provide early notification of any manufacturing interruptions or production changes that could lead to a supply disruption or the discontinuation of a product. Subsequently, the FDA improved its efforts to prevent shortages by expediting application reviews and inspections, exercising enforcement discretion in relevant cases, and helping manufacturers respond to quality control issues in drug manufacturing (Chen et al., 2016; GAO, 2016a).

WASTE AND COST DUE TO UNUSED DRUGS IN THE SUPPLY CHAIN

Every year drugs worth billions of dollars that have been purchased by health care organizations (e.g., retail pharmacies, hospitals, nursing homes) and patients are discarded. Some of this waste in the system could be eliminated by changing the way drugs are packaged and labeled. For example, vials of infused drugs are often available only in a single dose size that is

sufficient to treat a physically large patient. As a result, the remaining drug must be discarded when a smaller patient is treated. Because 18 of the top 20 infused cancer drugs are sold in just one or two vial sizes, 10 percent of the purchased drug amount is discarded on average (Bach et al., 2016). Manufacturers propose dose sizes for marketing, and the FDA only reviews the request for safety considerations (FDA, 2015). However, in Europe, where governments play a more active role than the United States does in drug pricing and distribution, many of these medicines are distributed in smaller vial sizes, reducing the potential for waste.

Many medicines are also discarded because of expiration dates (Allen, 2017). Since 1979 the FDA has required drug manufacturers to provide evidence of product stability, by subjecting drugs to various environmental variables such as temperature, humidity, and light, but there are no requirements for long-term testing. Pharmacies routinely discard stocked drugs when they reach their expiration date, but many drugs, if stored properly, are stable long beyond the expiration date on the label (Cantrell et al., 2012, 2017; Lyon et al., 2006). The strongest evidence comes from the FDA’s Shelf Life Extension Program (SLEP) (FDA, 2017c), which is funded by the U.S. Department of Defense to support the maintenance of its stockpiled drugs, worth billions of dollars. In a study of 122 different medication products, nearly 90 percent met the requirements for an extension; the average additional extension length by SLEP was 5.5 years, and some lots were extended by more than 20 years (Lyon et al., 2006).

Extending shelf life could not only reduce waste in the system, but also address shortages. The FDA recently posted updated expiration dates for batches of several different injectable drugs to help address ongoing critical shortages of these drugs used in critical care (FDA, 2017d). The American Medical Association and other entities have called for routinely collecting more data on long-term stability and revising expiration dates as appropriate (Diven et al., 2015). An independent organization could conduct more testing similar to that done by the FDA extension program. Information from the extension program also could be applied to properly stored medications.

Drugs worth billions of dollars are discarded each year by nursing homes and other long-term care facilities when they are no longer needed by residents (Allen, 2017; Coggins, 2016). A few states and nonprofit organizations have set up programs to collect, sort, and redistribute these unused drugs to reduce waste and costs to patients. However, in many areas no such programs exist (and in some cases are even illegal), so valuable drugs are simply discarded.

INSURANCE DESIGN

A key factor affecting the affordability of health care for individuals and families is whether a patient has health insurance. After the implementation of the ACA, the number of people with health insurance increased substantially, but approximately 10 percent of the population under age 65 has no health insurance—and hence no coverage for prescription drugs. Furthermore, not all of those with health insurance have insurance coverage for prescription drugs. This latter circumstance applies to both the under-65 population and those on Medicare. Fee-for-service Medicare helps cover the cost of prescription drugs for people who enroll in a Part D drug plan (see Figure 3-5), but enrollment is voluntary and only 42 million of the 57 million Medicare beneficiaries have Part D coverage (KFF, 2017b). However, of the remainder, some have drug coverage through employers, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, and other “creditable” sources (those that offer coverage as good as is provided by Part D), but a small share (about 12 percent) of Medicare beneficiaries lack a creditable source of drug coverage (MedPAC, 2017a). As of 2017, 99 percent of covered

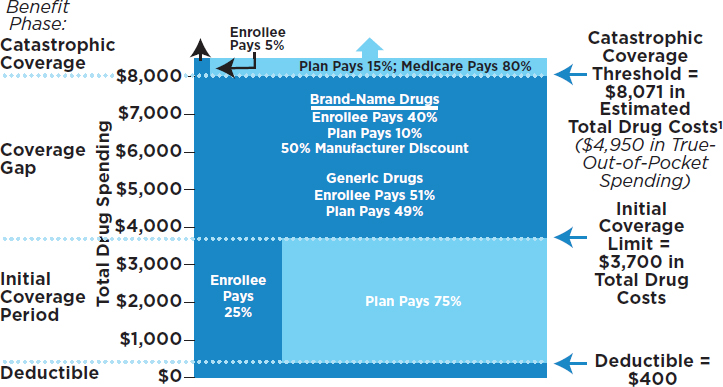

NOTES: Some amounts rounded to nearest dollar. 1Amount corresponds to the estimated catastrophic coverage limit for non-low-income subsidy (LIS) enrollees ($7,425 for LIS enrollees), which corresponds to a true out-of-pocket spending of $4,950, the amount used to determine when an enrollee reaches the catastrophic coverage threshold in 2017.

SOURCE: KFF, 2017.

employees worked for a firm whose largest health plan covered prescription drugs (KFF and Health Research & Educational Trust, 2017).

Recent changes in insurance design in the United States reflect the rising costs of not only drugs but all sectors of health care (Consumer Reports, 2016). As the costs of health care have risen, employers and insurers have modified benefit designs as a way to keep premiums as low as possible, with the goal of balancing cost and access. The escalating list prices of many branded drugs, especially specialty drugs and those that lack a competitor, have been a particular challenge in recent years.

As a result, even among those with insurance benefits, the out-of-pocket costs for premiums, deductibles, and copays can be substantial, and the design of the coverage and cost sharing can significantly affect the financial burden arising from prescription drug spending. Studies have found dramatic reductions in coverage generosity and shifts to percentage-based cost sharing for high-priced drugs over time (Doshi et al., 2016a; Dusetzina, 2016; Jung et al., 2016; Polinski et al., 2009; Yazdany et al., 2015), limiting options for patients to obtain plans that provide generous coverage for drugs. The specifics of pharmacy benefit design have the potential to be an important public health tool for improving patient treatment and adherence (Goldman et al., 2007) and can have a major effect on access to prescription medications (Delbanco et al., 2016).

The effects of high out-of-pocket spending can be significant for patients and their families. Increased cost sharing can reduce patient uptake and adherence to treatments, including specialty drugs (Alexander, 2003; Doshi et al., 2016a,b; Dusetzina et al., 2014; Fischer et al., 2011; KFF, 2015; Olszewski et al., 2017; RAND Health, 2006; Streeter et al., 2011; Winn et al., 2016). Nearly one-quarter of the Americans who participated in a 2015 survey reported that they had difficulty affording their prescription medicines. And nearly one-quarter reported that they or a family member had not filled a prescription that they had been provided, had skipped doses, or had reduced their dosage because of cost (KFF, 2015). One study of commercially insured adults with chronic myelogenous leukemia found that having higher out-of-pocket costs reduced patient adherence to therapy by 42 percent and increased the discontinuation of therapy by 70 percent (Dusetzina et al., 2013). A 2014 study on primary care found that approximately 31 percent of patients did not fill their prescriptions within the first 9 months after receiving them from a doctor. Additionally, the study found that patients with higher copayment fees, recent hospitalizations, severe comorbid conditions, or some combination of these three factors were less likely to fill their prescriptions (Tamblyn et al., 2014). Various studies confirm that poor adherence leads to negative clinical outcomes and increased health care costs (e.g., Roebuck et al., 2011).

Even for insured patients, the use of prescription drugs often entails a large out-of-pocket expense because of the high coinsurance rates that often apply to expensive drugs, particularly if the patients use specialty drugs or multiple high-cost brand-name drugs. For example, traditional Medicare currently places no upper limit on the total amount an individual may end up spending on cost sharing for Medicare-covered services. For services offered under Medicare Part B, including clinician-administered drugs, the beneficiaries (or their supplemental insurance plans) are responsible for 20 percent of the cost (MedPAC, 2016), and there are no catastrophic coverage limits. In 2014, virtually all Part D formularies required coinsurance of between 25 and 33 percent for cancer drugs, the maximum allowed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) (Dusetzina and Keating, 2015). This can translate to hundreds or even thousands of dollars annually in out-of-pocket costs for higher-cost medications.

Individuals with employer-sponsored or other types of private health insurance also face challenges with prescription drug costs. As noted above, in response to increasing costs across all sectors of health care, insurance companies have raised deductibles, increased monthly premiums, imposed or increased copays and coinsurance, and transferred high-cost drugs to more expensive formulary tiers (Claxton et al., 2017; Consumer Reports, 2016). Among employer-sponsored plans, deductibles grew from 4 percent of cost-sharing payments in 2004 to 24 percent in 2014; coinsurance increased from 3 to 20 percent over that same period (Cox, 2016). A patient’s costs often depend on the tiered structure by which many health plans organize the drugs that are covered by their formularies.

Private health insurance plans have been moving to three- or four-tier coinsurance or copayment structures that require a smaller degree of cost sharing for generics and a greater degree for higher-cost drugs especially when there are therapeutically equivalent options (KFF, 2014). Plan tiers often include preferred, non-preferred, and generic drugs, and each tier of drugs can represent a different level of cost sharing or class of drugs, such as specialty drugs (KFF and Health Research & Educational Trust, 2017). However, every plan, whether Part D or an employer-sponsored pharmacy benefit, has an exception process that permits coverage of a drug not on formulary or reduce out-of-pocket cost if a physician provides information about side effects the patient has experienced from a lower-tiered drug or offers another medical reason for switching.

As noted in Box 2-1, most large employers self-finance their health insurance contributions for their employees and hence have a direct and significant interest in controlling health care costs. As of 2017, 91 percent of employees covered by employer-sponsored insurance plans were in a plan with tiered cost sharing (KFF and Health Research & Educational Trust, 2017). The ubiquity of such plans can influence how much individuals cov-

ered by specific employer-sponsored plans pay due to the variation in cost sharing. The Kaiser/Health Research & Educational Trust 2017 Employer Health Benefits Survey of workers covered by employer-sponsored plans found that, among those in plans with at least three tiers of cost sharing, the average copayment per drug was $11 for the first tier and $110 for the fourth tier. The average coinsurance was 17 percent for first-tier drugs and 38 percent for third-tier drugs. Specialty drug tiers tend to drive up cost sharing even further, with an average copayment of $101 and an average coinsurance rate of 27 percent for drugs on a specialty tier. In addition to copayments and coinsurance, health plans can apply an additional deductible to drugs that is separate from the general annual deductible. In 2017, 15 percent of workers with prescription drug coverage had to meet a prescription drug–only deductible (KFF and Health Research & Educational Trust, 2017).

Health plan decisions regarding which drugs to include in their formularies—and in which tiers—also reflect the influence of PBMs, whose negotiations often occur with minimal transparency or data on rebate amounts, raising concerns about their impact on patients’ out-of-pocket spending (Health Affairs, 2017b). However, Part D plans do enable consumers to determine and compare the out-of-pocket costs of a drug in the “preferred pharmacy network,” “non-preferred networks,” and mail-order services.

“High-deductible health plans” are also becoming more common in the U.S. insurance marketplace as health care costs rise (Claxton et al., 2016). These plans require a higher deductible than most health plans, in exchange for a lower monthly premium. High-deductible health plans require consumers to cover 100 percent of their health care costs up to a certain amount—the deductible—at which point their insurance coverage and other cost-sharing arrangements begin. In 2016, nearly 30 percent of individuals in employer-sponsored plans were enrolled in a high-deductible health plan (Claxton et al., 2016). Recent work has begun to explore the clinical and economic benefits of high-deductible plans in the long run (Fronstin et al., 2013).

Out-of-Pocket Spending and Specialty Drug Access

Many oral drugs used to treat complex conditions such as HIV, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, cancer, and hepatitis C are costly, and the increasing use of deductibles and coinsurance in the pharmacy benefit offered by insurance plans may lead to significant financial hardship for patients needing treatment. Medicare beneficiaries are exposed to high costs in two primary ways. First, enrollees who take drugs covered on a Part D plan’s specialty tier face coinsurance rates of between 25 percent

and 33 percent of the drug’s total price during the initial coverage phase. In 2017 the Part D standard benefit has a $400 deductible and 25 percent coinsurance up to an initial coverage limit of $3,700 in total drug costs, followed by a coverage gap (see Figure 3-5). During the gap, enrollees are responsible for a larger share of their total drug costs than in the initial coverage period, until their total out-of-pocket spending in 2017 reaches $4,950. After enrollees reach the catastrophic coverage threshold, Medicare pays for most (80 percent) of their drug costs, plans pay 15 percent, and enrollees pay 5 percent of total drug costs. Second, even patients who reach the catastrophic coverage threshold of Medicare Part D can be exposed to high costs because the threshold is not a hard cap on out-of-pocket costs. For medications costing tens of thousands of dollars or more per year, patients can spend more out of pocket during the catastrophic phase than in the other benefit phases combined (Hoadley, 2015). A recent analysis found that 3.6 million Medicare beneficiaries had total drug spending above the Part D catastrophic threshold in 2015, and of those, one million incurred out-of-pocket drug costs above the threshold (KFF, 2017a).

Two examples illustrate the extent to which Part D enrollees can be exposed to serious financial risk, despite the Part D benefit’s catastrophic coverage, when the underlying price of the drug they take is very high. For Harvoni, a breakthrough treatment for hepatitis C, a patient enrolled in Part D in 2016 faced total out-of-pocket costs of $7,153 for a course of treatment, but 61 percent of this total was incurred in the catastrophic coverage phase. For Revlimid, a cancer drug, a patient enrolled in Part D in 2016 faced total annual out-of-pocket costs of $11,538 for this drug alone in 2016, 76 percent of which was in the catastrophic coverage phase of the benefit. (The price for Revlimid has since increased dramatically, to more than $18,000 per fill; thus, in the catastrophic phase under Part D, enrollees will pay more than $900 per month for this drug [Court, 2017].)

One way to strengthen financial protections for Medicare beneficiaries with very high drug costs would be to eliminate enrollees’ cost sharing above the catastrophic coverage threshold, thereby making the current catastrophic coverage threshold an absolute limit on out-of-pocket spending under Part D. This proposal has been recommended by the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC, 2016). To mitigate the concern that pharmaceutical companies might respond by simply raising their list prices, one strategy might be to increase the share of total costs that Part D plan sponsors pay in the catastrophic coverage phase of the benefit (up from the current 15 percent), giving them a stronger financial incentive to negotiate larger rebates for higher-priced drugs and to take more steps to manage the use of these drugs by their enrollees, which could produce savings for enrollees, Medicare, and the plans themselves.

PATIENT ASSISTANCE PROGRAMS

Patient assistance programs supported by drug manufacturers serve to lower patients’ out-of-pocket spending by covering the cost of all or part of their out-of-pocket expenses when they buy brand-name medications. This practice may bring the price that patients pay for branded medications closer to—and in some cases lower than—the price of generic alternatives, but it does not change the cost to the insurer. In fact, such practices serve to increase costs to insurers and therefore, the premiums charged by the insurer. These practices also lessen the insurer’s ability to price discriminate (through the use of tiers in the formulary), as patients with access to these programs will often opt for branded products over generics and, more generally, choose drugs not “preferred” by the plan (Ubel and Bach, 2016).

The popularity of patient assistance programs among both patients and manufacturers has increased over time (Daubresse et al., 2017; Ross and Kesselheim, 2013). Assistance programs are delivered through a variety of mechanisms, including coupons, drug savings cards, manufacturer assistance programs (provided through the drug maker), access networks that create disease-specific funds, and disease-focused foundation programs. Payments are generally distributed via clinicians’ offices or, increasingly, directly to the patient through the mail or online (Dafny et al., 2016b). Support can include providing medications or payments directly to individuals. Eligibility for support from these sources varies by insurance status and income. Some types of copayment assistance are not allowed, including the use of manufacturer coupons to pay for drugs obtained through Medicare Part D benefits.

While helpful in some ways, patient assistance programs encourage patients to use higher-cost branded products, since generic manufacturers do not typically offer assistance programs. Patients with very high deductibles or with high coinsurance requirements may find it difficult to pay the out-of-pocket costs to obtain high-priced drugs. In such cases, patients may need to access assistance programs in order to offset the out-of-pocket costs of starting and adhering to therapy, regardless of their insurance status. Each program is a unique, unregulated, private offering by a pharmaceutical company for an individual product. The application process can be onerous for patients and clinicians, with a high probability of rejection, commonly based on patient income level and insurance coverage. There is little information available to evaluate the impact of patient assistance programs so few studies have examined the proportion of patients served, the extent of aid provided, the criteria for qualifying for aid, and the estimated financial cost to society (Felder et al., 2011).

Drug manufacturers tend to use coupons to promote the use of branded expensive products when less expensive alternatives are available (Dafny

et al., 2016b; Ross and Kesselheim, 2013). One analysis estimated that copay coupons increased branded drug sales by 60 percent or more, almost entirely by reducing the sales of generic competitors, and that they had the potential to undermine the efforts of prescription drug insurance plans (Dafny et al., 2016a). Federal policies prohibit the use of manufacturer coupons in paying for medications paid for by Medicare Part D because it is considered a violation of anti-kickback statues and it raises costs to the government (OIG, 2014).

FEDERAL DISCOUNT PROGRAMS

Medicaid Drug Rebate Program

The U.S. Congress created the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program (MDRP), which went into effect in 1991, resulting from the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990 in an attempt to address the rising cost of prescription drugs in the Medicaid program. In the MDRP, the drug manufacturer enters into a rebate agreement with the HHS secretary in return for Medicaid coverage of all products made by this manufacturer, as well as payments for covered outpatient drugs provided through Medicare Part B. This has essentially created an open formulary in Medicaid. CMS reports that about 600 manufacturers have entered into such an agreement (CMS, 2017a).

Unlike most rebates for prescription drug spending, the rebates obtained through the MDRP are not negotiated, but are defined by statute. However, many components used to calculate the rebate are proprietary, and as a result, it is difficult to calculate exactly how much Medicaid spends on a particular drug. This contributes to the lack of transparency surrounding drug pricing. Statutory rebates are set by the U.S. Congress and enacted into law, and there have been changes over time. States are free to negotiate supplemental rebates on top of the statutory rebates.

The basic rebate calculation for single-source drugs and innovator multiple-source drugs8 is set by statute and is set separately for non-innovator, multiple-source drugs. For single-source and innovator multiple-source drugs, the unit rebate amount is equal to the greater of either the product of Average Manufacturer Price (AMP) times 23.1 percent or the difference between AMP and the Best Price (defined as the lowest

___________________

8 “Innovator drugs” include both single-source (typically a brand-name product that has no available generic versions) and multiple-source (typically a brand-name product that has available generic versions) products. “Non-innovators” are typically generic versions of multiple-source drugs (OIG, 2009). Statute sets different rebate percentages for certain types of single-source and innovator multiple-source drugs: clotting factors and drugs approved by the FDA exclusively for pediatric indications.

price the manufacturer charges any wholesaler, health maintenance organization, retailer, health care provider, government entity, or nonprofit organization in the United States during that rebate period). For non-innovator, multiple-source drugs, the unit rebate amount is equal to the product of AMP times 0.13. The rebate on innovator drugs includes an adjustment to account for price inflation; however, this adjustment is not included in the rebates for non-innovator drugs. There are some important exceptions to the “best price” provision, including prices charged in the 340B program to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, the U.S. Department of Defense, Medicare Part D, and Indian Health Service. This seemingly minor part of the MDRP has a major implication: outside of these exceptions, manufacturers are very reluctant to provide rebates for single-source or innovator multiple-source drugs large enough to trigger the “best price” provision because it would create a lower price for the entire Medicaid program (Health Affairs, 2017a).

Rebates are paid by drug manufacturers on a quarterly basis to states and are shared between the states and the federal government. Prior to the ACA, rebates through the MDRP were only available for drugs provided in fee-for-service settings. Under the ACA, drugs provided in managed care settings are also eligible for rebates and as a result, states have increasingly been providing the Medicaid prescription drug benefit through managed care.