3

Essential Clinical Competencies for Abortion Providers

Chapters 1 and 2 describe the elements of the continuum of abortion care services, including current abortion methods, relevant side effects and risks for complications, the appropriate clinical settings for the various abortion methods, state regulations affecting the quality of abortion care, and best practices for delivering high-quality, safe abortion care.

As part of its charge (see Box 1-1 in Chapter 1), the committee was tasked with reviewing the evidence on the clinical skills necessary for health care providers to safely perform the various components of abortion care, including pregnancy determination, counseling, gestation assessment, medication dispensing, procedure performance, patient monitoring, and follow-up assessment and care. Provider skills and training—significant factors that influence the safety and quality of abortion care—are the subject of this chapter.

Thus, this chapter identifies the clinical competencies for providing abortion care safely and with the highest degree of quality, the types of providers with the clinical competence to perform abortions, current abortion training of physicians and advanced practice clinicians (APCs), and the availability of appropriately trained clinicians. The chapter also describes the types of clinicians who provide abortion care in the United States; the available literature on the safety and quality of the care they provide; and current opportunities for education and training, including factors that affect the integration of abortion care in clinician education and training. A diverse range of providers can and do provide abortion care, although large-scale studies are generally limited to obstetrician/gynecologists (OB/GYNs), family medicine physicians,

and APCs. This chapter focuses on these provider types because of the available data, but the committee recognizes that clinicians in other physician and health care specialties provide abortions and can be trained to provide safe and high-quality abortion care. This chapter also reviews abortion-specific state laws and policies that regulate the level of training and credentialing clinicians must have to be allowed to provide abortion services in different states. Finally, whereas this chapter focuses on provider skills and training, it is assumed the continuum of abortion care is being provided in a safe, well-organized setting/system of care and in an evidence-based manner, as described in Chapter 2.

REQUIRED CLINICAL COMPETENCIES

To determine the evidence-based, clinical competencies essential to providing high-quality abortion services, the committee reviewed clinical guidelines and training materials published by organizations that provide clinical guidance and continuing education to health professional students and clinicians. These sources include recommendations and standards issued by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), Society of Family Planning (SFP), National Abortion Federation (NAF), Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG), World Health Organization (WHO), University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Bixby Center for Global Reproductive Health, Kenneth J. Ryan Residency Training Program, Fellowship in Family Planning, Reproductive Health Education in Family Medicine (RHEDI), Reproductive Health Access Project, and others.

For any clinical skill set, competency levels build on basic knowledge, didactic curriculum, clinical training, and continuing education. Key to the safety and quality of abortion services is having appropriate linkages in the continuum of care from preabortion services to postabortion services.

Some components of abortion care are consistent regardless of the particular abortion method; therefore, a number of essential competencies are required for any type of abortion procedure. These competencies have been outlined by several organizations, including the UCSF Bixby Center for Global Reproductive Health, NAF, the Fellowship in Family Planning, and the Ryan Residency Training Program, and include

- patient preparation (education, counseling, and informed consent);

- preprocedure assessment to confirm intrauterine pregnancy and assess gestation;

- pain management during and after the procedure;

- complication assessment and management; and

- provision of postabortion contraception and contraceptive counseling.

Additionally, the different abortion methods outlined in Chapter 2 (medication, aspiration, dilation and evacuation [D&E], and induction) require procedure-specific competencies. Increased gestation corresponds with increased procedural complexity; therefore, procedures performed later in pregnancy require more complex clinician competencies. See Table 3-1 for a list of all competencies by procedure type.

Patient Preparation

As noted in Chapter 2, patient preparation involves providing information to the patient about the available abortion methods (including pain

TABLE 3-1 Required Competencies by Type of Abortion Procedure

| Competencies | Type of Procedure | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medication Abortion | Aspiration Abortion | Dilation and Evacuation (D&E) | Induction Abortion | |

| Patient preparation (education, counseling, and informed consent) | ||||

| Preprocedure evaluation | ||||

| Complication assessment and management | ||||

| Cervical preparation | ||||

| Administration of abortion medications | ||||

| Use of a manual or power vacuum extractor | ||||

| Forceps extraction | ||||

| Identification of products of conception | ||||

| Contraception provision | ||||

| Pain management (techniques of analgesia and anesthesia) | ||||

SOURCES: ACOG, 2015; ACOG and SFP, 2014; Allen and Goldberg, 2016; Baird et al., 2007; Baker and Beresford, 2009; Creinin and Danielsson, 2009; Davis and Easterling, 2009; Goldstein and Reeves, 2009; Goodman et al., 2016; Hammond and Chasen, 2009; Kapp and von Hertzen, 2009; Meckstroth and Paul, 2009; NAF, 2017; Newmann et al., 2008, 2010; RCOG, 2015; SFP, 2014.

management options), the advantages and disadvantages of each method, potential side effects and risks for complications, and contraceptive options (ACOG and SFP, 2014; Goodman et al., 2016; NAF, 2017; Nichols et al., 2009; RCOG, 2015). For patients opting for sedation, a presedation evaluation is recommended (NAF, 2017). The patient’s voluntary and informed consent for the procedure must also be obtained (Baker and Beresford, 2009; Goodman et al., 2016; NAF, 2017). During this process, the provider should provide accurate and understandable information and engage in shared decision making with the patient. Shared decision making is a process in which clinicians and patients work together to make decisions and select tests, treatments, and care plans based on clinical evidence that balances risks and expected outcomes with patient preferences and values (Health IT, 2013).

Preprocedure Assessment

A combination of diagnostic tests and physical examination can be used to confirm intrauterine pregnancy; assess gestation; screen for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and cervical infections; document Rh status; and evaluate uterine size, position, anomalies, and pain (Goldstein and Reeves, 2009; Goodman et al., 2016; NAF, 2017; RCOG, 2015). Screening for anemia and evaluation for risk of bleeding are typically part of this preprocedure assessment and are often done by hemoglobin or hematocrit testing (NAF, 2017). Appropriate assessment also involves a medical history to determine relevant chronic or acute medical conditions, clinical risks, potential medication contraindications, and necessary modifications to care. Evaluation is necessary for developing a patient-centered clinical plan, determining the appropriate method and setting of abortion care, and knowing when to refer patients in need of more sophisticated clinical settings (Davis and Easterling, 2009; Goodman et al., 2016; RCOG, 2015).

Pain Management and Patient Support

Pain management varies based on patient preference, method of abortion, gestation, facility type, and availability of patient support from staff or others. Analgesia, anesthesia, and nonpharmacological pain management methods and risks are described in Chapter 2.

A member of the care team should discuss these options and risks with the patient during the patient preparation process, and if the patient opts for sedation, a presedation evaluation should be performed (Goodman et al., 2016; NAF, 2017; Nichols et al., 2009). A presedation evaluation includes relevant history and review of systems; medication

review; targeted exam of the heart, lung, and airway; baseline vital signs; and last food intake (NAF, 2017). Providers must be able to administer paracervical blocks and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to patients (NAF, 2017). If the patient opts for sedation or anesthesia, a supervising practitioner, appropriately trained to administer anesthesia and appropriately certified according to applicable local and state requirements, must be available (Goodman et al., 2016; NAF, 2017). To administer moderate sedation, NAF requires that a provider have appropriate licensure, basic airway skills, the ability to monitor and effectively rescue patients in an emergency, and the ability to screen patients appropriately (NAF, 2017). As noted above, providers must have the necessary resources and protocols for managing procedural and anesthesia complications and emergencies.

Procedure-related pain is a complex phenomenon influenced by multiple factors, including past history, anxiety, and individual tolerance. Relevant information about anticipated discomfort and options for pain management should be covered by the clinician during the informed consent process (Goodman et al., 2016; Nichols et al., 2009). The clinician should have a thorough understanding of potential side effects and complications from medications used to control pain.

Complication Assessment and Management

Assessment and management of abortion complications and medical emergencies are a key component of quality abortion care. Chapter 2 describes the types of complications that may require clinical follow-up. Although adverse events are rare, providers must have the ability to recognize conditions and risk factors associated with complications (e.g., accumulation of blood, retained tissue, excessive bleeding, and placental abnormalities) and have the resources or protocols necessary to manage these rare events. NAF and the UCSF Bixby Center recommend that providers have established protocols for medical emergencies, including bleeding and hemorrhage, perforation, respiratory arrest/depression, and anaphylaxis, and for emergency transfer (Goodman et al., 2016; NAF, 2017).

Contraception Provision and Counseling

Providing evidence-based information on how to prevent a future unintended pregnancy—including the option to obtain contraception contemporaneously with the procedure—is a standard component of abortion care (Goodman et al., 2016; NAF, 2017; RCOG, 2015; WHO, 2014). Contraceptive counseling should be patient-centered and guided by the patient’s preferences (Goodman et al., 2016; RCOG, 2015). After the

abortion, patients should receive the contraceptive method of their choice or be referred elsewhere if the preferred method is unavailable (NAF, 2017; RCOG, 2015; WHO, 2012). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the U.S. Office of Population Affairs recommend the following for providers offering contraceptive services, including contraceptive counseling and education (Gavin et al., 2014):

- Establish and maintain rapport with the client.

- Obtain clinical and social information from the client (medical history, pregnancy intention, and contraceptive experiences and preferences).

- Work with the client interactively to select the most effective and appropriate contraceptive method (providers should ensure that patients understand the various methods’ effectiveness, correct use, noncontraceptive benefits, side effects, and potential barriers to their use).

- Conduct a physical assessment related to contraceptive use, when warranted.

- Provide the selected contraceptive method along with instructions for its correct and consistent use, help the client develop a plan for using the selected method and for follow-up, and confirm the client’s understanding of this information.

Competencies Required for Abortion Methods

Medication Abortion

Medication abortion is a method commonly used to terminate a pregnancy up to 70 days’ (or 10 weeks’) gestation with a combination of medications—mifepristone followed by misoprostol. The skill set required for early medication abortion has been outlined by several organizations and is similar to the management of spontaneous loss of a pregnancy with medications (Goodman et al., 2016). The skills include the essential competencies outlined in the section above, plus the knowledge of medication abortion protocols, associated health effects, and contraindications. Prescribing medication abortion is no different from prescribing other medications—providers must be able to recognize who is clinically eligible; counsel the patient regarding medication risks, benefits, and side effects; and instruct the patient on how to take the medication correctly and when to seek follow-up or emergency care.

Chapter 2 describes the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) for Mifeprex, the brand name for mifepristone, the first drug administered during a medication

abortion. Distribution of Mifeprex is restricted to REMS-certified health care providers, but any physician specialty or APC can become certified. In March 2016, the FDA issued revisions to the label and REMS for Mifeprex, changing the language from “physician” to “health care provider” and thereby expanding opportunities for APCs with relevant clinical competencies to obtain and distribute the drug (Simmonds et al., 2017; Woodcock, 2016). A component of the REMS process requires prescribers of Mifeprex to meet the following qualifications (FDA, 2016; Woodcock, 2016):

- ability to assess the duration of pregnancy accurately;

- ability to diagnose ectopic pregnancies; and

- ability to provide surgical intervention in cases of incomplete abortion or severe bleeding or have made plans to provide such care through others, and ability to ensure patient access to medical facilities equipped to provide blood transfusions and resuscitation, if necessary.

Aspiration Abortion

Aspiration abortion is a minimally invasive procedure that uses suction to empty the uterus. Aspiration abortion is an alternative to medication abortion up to 70 days’ (or 10 weeks’) gestation and the primary method of abortion through 13 weeks’ gestation (Jatlaoui et al., 2016). The procedure and required skills are the same as those for the management of spontaneous loss of a pregnancy with uterine aspiration (Goodman et al., 2016; Nanda et al., 2012). The essential competencies for all abortion procedures form the basis of the skill set required for aspiration abortion. Additional competencies have been defined by the UCSF Bixby Center and NAF (Goodman et al., 2016; NAF, 2017). They include cervical preparation, experience with manual or electric vacuum aspiration, and evaluation of the products of conception for appropriate gestational tissue.

Dilation and Evacuation (D&E)

D&E is usually performed starting at 14 weeks’ gestation, and most abortions after 14 weeks’ gestation are performed by D&E (ACOG, 2015; Hammond and Chasen, 2009; Jatlaoui et al., 2016; O’Connell et al., 2008; Stubblefield et al., 2004). The procedure and required skills are similar to those for the surgical management of miscarriage after 14 weeks’ gestation (Nanda et al., 2012). D&E requires clinicians with advanced training and/or experience, a more complex set of surgical skills relative to those required for aspiration abortion, and an adequate caseload to maintain these surgical skills (Gemzell-Danielsson and Lalitkumar, 2008;

Grossman et al., 2008; Hammond and Chasen, 2009; Hern, 2016; Kapp and von Hertzen, 2009; Lohr et al., 2008; RCOG, 2015). The additional skills required for D&E include surgical expertise in D&E provision and training in the use of specialized forceps. Cervical preparation, achieved by osmotic dilators or prostaglandin analogues (misoprostol), is standard practice for D&E after 14 weeks’ gestation (Newmann et al., 2008, 2010; SFP, 2014).

Induction Abortion

Induction abortion is the termination of pregnancy using medications to induce delivery of the fetus. Induction abortion requires a clinician skilled in cervical preparation and delivery (ACOG, 2015; Baird et al., 2007; Hammond and Chasen, 2009; Kapp and von Hertzen, 2009). As with any woman in labor, providing supportive care for women undergoing induction abortion is of utmost importance. Physical as well as emotional support should be offered (Baird et al., 2007). Women should be encouraged to have a support person with them if possible.

WHICH PROVIDERS HAVE THE CLINICAL SKILLS TO PERFORM ABORTIONS?

While OB/GYNs provide the greatest percentage of abortions (O’Connell et al., 2008, 2009), other types of clinicians (both generalist physicians and APCs) also perform abortions. The committee identified systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials, and a variety of cohort studies assessing the outcomes of abortions provided by family medicine physicians or comparing the outcomes of abortions performed by physicians and nurse practitioners (NPs), certified nurse-midwives (CNMs), and/or physician assistants (PAs) (Bennett et al., 2009; Goldman et al., 2004; Kopp Kallner et al., 2015; Ngo et al., 2013; Paul et al., 2007; Prine et al., 2010; Renner et al., 2013; Weitz et al., 2013). Many of the comparative studies were based in parts of the world where provider shortages are particularly acute, often in developing countries. All the available systematic reviews include this international research and also judge much of the research to be of poor quality (Barnard et al., 2015; Ngo et al., 2013; Renner et al., 2013; Sjöström et al., 2017). The literature is less robust regarding other generalist physicians, yet the same judgment and clinical dexterity necessary to perform first-trimester abortion are possessed by many specialties.

This section reviews the primary research on which providers have the clinical skills to provide abortions that is most relevant to the delivery of abortion care in the United States. It is noteworthy that numerous professional and health care organizations, including ACOG, NAF, the American

Public Health Association, WHO, and others,1 endorse APCs providing abortion care (ACOG, 2014a,b; APHA, 2011; Goodman et al., 2016; NAF, 2017; WHO, 2014, 2015).

Medication and Aspiration Abortion

Advanced Practice Clinicians

The committee identified three primary research studies that assessed APCs’ skills in providing either medication or aspiration abortions.

The Health Workforce Pilot Project (HWPP) was a 6-year multisite prospective clinical competency-based training program and study sponsored by the Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health (ANSIRH) program at the UCSF Bixby Center. The project was designed to train APCs to competence in the provision of aspiration abortion and to evaluate the safety, effectiveness, and acceptability of APCs providing abortion care, in an effort to expand the number of trained providers in California (ANSIRH, 2014; Levi et al., 2012; Weitz et al., 2013). The project received a waiver from the California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD) to proceed with the study because of an existing statute that limited the provision of aspiration abortion to physicians (Weitz et al., 2013). The project used the Training in Early Abortion for Comprehensive Healthcare model, which combines didactic learning, clinical skill development, and a variety of evaluation methods to ensure clinical competency (Levi et al., 2012).

Weitz and colleagues (2013) evaluated the patient outcomes of aspiration abortions provided between August 2007 and August 2011 by physicians and APCs from five partner organizations, trained to competence through HWPP. The analysis included 11,487 aspiration abortions performed by 40 APCs (n = 5,675) and 96 OB/GYN or family medicine physicians (n = 5,812). The complication rate was 1.8 percent for APCs and 0.9 percent for physicians, with no clinically relevant margin of difference (95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.11, 1.53) (Weitz et al., 2013). The authors concluded that APCs can be trained to competence in early abortion care and provide safe abortion care.

The patients in the study (n = 9,087) completed a survey after their abortions to enable the investigators to assess the women’s experience,

___________________

1 The American Academy of Physician Assistants, the American College of Nurse-Midwives, the American Medical Women’s Association, the Association of Physician Assistants in Obstetrics and Gynecology, the International Confederation of Midwives, the National Association of Nurse Practitioners in Women’s Health, and Physicians for Reproductive Choice and Health also support an increased role for appropriately trained APCs (ACNM, 2011b; ICM, 2011b; NAF and CFC, 2018).

access to care, and health; regardless of clinician type, the patient experience scores were very high (Taylor et al., 2013). Treatment by staff, timeliness of care, and level of pain were factors that highly impacted women’s rating of their experience, but patient experience was not statistically different by clinician type after controlling for other patient- and clinic-level factors.

A qualitative analysis of the women’s responses to the survey’s open-ended question on their experience (n = 5,214) was conducted to determine themes across the responses (McLemore et al., 2014). The responses were categorized into themes of factors at the patient level (experiences of shame/stigma, pain experience, and interactions with staff) and clinic level (perceptions of clinical environment, adequate pain management, and wait time). Almost 97 percent of respondents reported their patient experience to be what they had expected or better. Major themes identified in the responses by women who reported their experience to have been worse than expected included issues with clinical care (problems with intravenous line insertion and/or preprocedure ultrasound, uncertainty about abortion completion, and needing subsequent follow-up appointments), level of pain experienced, and frustration with wait times for appointments and within the clinic.

In summary, the HWPP studies found that aspiration abortions were performed safely and effectively by both APCs and physicians and with a high degree of patient satisfaction (McLemore et al., 2014; Taylor et al., 2013; Weitz et al., 2013). The project, overseen by OSHPD, was completed in 2013, and the study results supported new legislation2 in California that expanded the scope of practice for APCs to include early abortion care.

Two smaller studies compared the outcomes of abortions performed by APCs and physicians. In a 2-year prospective cohort study, Goldman and colleagues (2004) analyzed the outcomes of aspiration abortions provided by three PAs in a Vermont clinic (n = 546) and three physicians (n = 817) in a New Hampshire clinic. The authors found no statistically significant difference3 in the complication rates of the two types of clinicians. Kopp Kallner and colleagues (2015) conducted a nonblinded randomized equivalence trial comparing medication abortions (using the WHO protocol and routine ultrasound) performed by 2 nurse-midwives and 34 physicians in Sweden. The primary outcome was defined as successful completion of the abortion without the need for a follow-up aspiration procedure. Complication rates and women’s views on the acceptability of nonphysician providers were also assessed. The results showed superiority for the nurse-midwife group. The risk ratio for the physician group was 2.5 (95% CI =

___________________

2 California Assembly Bill No. 154 to amend California Business and Professions Code, Section 2253 and California Health and Safety Code, Section 123468.

3 The threshold for statistical significance was p ≤.05.

1.4, 4.3). The researchers concluded that using nurse-midwives to provide early medication abortions is highly effective in high-resource areas such as theirs.

Family Medicine Physicians

Multiple studies have concluded that family medicine physicians provide medication and aspiration abortions safely and effectively (Bennett et al., 2009; Paul et al., 2007; Prine et al., 2003, 2010) with a high degree of patient satisfaction (Paul et al., 2007; Prine et al., 2010; Summit et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2015). In one study of 2,550 women who sought abortions in five clinical settings from family physicians, medication and aspiration procedures had a 96.5 percent and 99.1 percent success rate, respectively (Bennett et al., 2009). All complications were minor and managed effectively at rates similar to those in OB/GYN practices and specialty abortion clinics. Another study of 847 medication abortions in a family medicine setting similarly found that the abortions were as safe and effective as those provided in specialty clinics (Prine et al., 2010).

The literature is less robust regarding other generalist physicians. However, the same judgment and clinical dexterity necessary to perform medication and aspiration abortions are obtained in other specialty training.

D&E and Induction Abortions

The committee could identify no comparative studies of clinicians who perform D&E and induction abortions. In the United States, D&Es are performed by OB/GYNs, family medicine physicians, or other physicians with advanced training and/or experience (such as the training provided in specialized fellowships) (O’Connell et al., 2008; Steinauer et al., 2012). In general, OB/GYNs have the most experience in the surgical techniques used to perform a D&E abortion. Induction abortion can be provided by a team of providers with the requisite skill set for managing women in labor and during delivery, such as OB/GYNs, family medicine physicians, and CNMs (Gemzell-Danielsson and Lalitkumar, 2008).

TRAINING OF PHYSICIANS AND ADVANCED PRACTICE CLINICIANS

Although most women’s health care providers will interact with patients navigating issues of unintended pregnancy and abortion, abortion training is not universally available to physicians or APCs who intend to provide reproductive health services. Evidence suggests that few education programs incorporate abortion training in didactic curriculum, and only

a small percentage of residencies, regardless of type or specialty, with the exception of OB/GYN, offer integrated abortion training (Herbitter et al., 2011, 2013; Lesnewski et al., 2003; Steinauer et al., 1997; Talley and Bergus, 1996; Turk et al., 2014).

Many factors influence the availability of training, including geography, institutional policy, and state law. Additionally, training has become more limited as a result of religious hospital mergers, state restrictions on medical schools and hospitals used for training programs, and training inconsistencies (Goodman et al., 2016). Catholic and Catholic-owned health care institutions are the largest group of religiously owned nonprofit hospitals, governing 15 percent of all acute care hospitals and 17 percent of hospital beds in the United States, and in many areas, these institutions function as the sole community hospital.4 Employees at these institutions are bound by Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services, which prohibits providing and teaching certain reproductive services, including abortion (Freedman and Stulberg, 2013; Freedman et al., 2008; Stulberg et al., 2016). Medical students, residents, and other health professional students are often responsible for seeking out learning opportunities themselves, as almost all abortions are provided outside of the traditional health care trainee learning environment (ACOG, 2014a,b).

Obstetrics and Gynecology

The organization that accredits allopathic (and by 2020, also osteopathic) residencies in the United States is the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). The ACGME training requirements for OB/GYN state that (1) programs must provide training or access to training in the provision of abortions, and this must be part of a planned curriculum; (2) residents who have religious or moral objections may opt out and must not be required to participate; and (3) residents must have experience in managing complications of abortions and training in all forms of contraception, including reversible methods and sterilization (ACGME, 2017b). Although this requirement has been in place since 1996, a number of OB/GYN residency programs do not provide specific training in abortion, and others provide such training only at the request of the resident (opt-in training). In 1995, Congress passed the Coates Amendment of the Omnibus Consolidated Rescissions and Appropriations Act of 1996,5 which upholds the legal status and federal funding of institutions that do

___________________

4 Designated by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services if the hospital is at least 35 miles from other like hospitals or if travel time between the hospital and the nearest like hospital is at least 45 minutes.

5 S971, 104th Congress, 1st session (1995).

not provide abortion training or referrals for residents seeking such training elsewhere (Tocce and Severson, 2012). While the federal funding to these institutions may be preserved, this legislation does not shield institutional residency programs from the need to comply with the accreditation requirements put forth by ACGME.

Although the majority of abortion providers are OB/GYNs (O’Connell et al., 2008, 2009), available data indicate that most OB/GYNs do not provide abortions. Stulberg and colleagues (2011) surveyed practicing OB/GYNs in 2008–2009 using the American Medical Association Physician Masterfile to determine the extent to which OB/GYNs were providing abortions. Of the 1,144 respondents, 14.4 percent provided abortions, whereas 97 percent reported encountering an abortion-seeking patient. OB/GYNs located in the Northeastern or Western United States and those whose zip code was greater than 90 percent urban were most likely to provide abortions (Stulberg et al., 2011). According to the most recent data collected from NAF members, approximately 64 percent of NAF member providers who performed first-trimester surgical abortions in 2001 were OB/GYNs (O’Connell et al., 2009). These are the most recent data available for NAF members, but given the growing percentage of medication abortions before 10 weeks’ gestation and expanded opportunities for other types of providers, APCs and family physicians may now represent an increased share of abortion providers.

A 2014 study of OB/GYN fourth-year residents associated with 161 of the 248 total residency programs found that 54 percent of residents reported routine abortion training; 30 percent reported opt-in training, where the training was available but not integrated; and 16 percent reported that training in elective abortion was unavailable in their program (Turk et al., 2014). Previous studies have found training participation rates to be very low among programs with optional training (Almeling et al., 2000; Eastwood et al., 2006).

From their general training, OB/GYN physicians may be more experienced with the surgical techniques of D&E and dilation and sharp curettage (D&C) relative to medication abortion (ACOG, 2015). In a 2007 survey of OB/GYNs who had recently completed their residencies, 65.1 percent reported receiving training in D&C, 62.0 percent in D&E, and 60.2 percent in induction. Residents had received the least training in medication abortion—40.7 percent reported training in mifepristone and misoprostol provision, 43.5 percent in manual vacuum aspiration (MVA), and 45.1 percent in electric vacuum aspiration. Thus, the residents had received more training in abortion procedures that are performed after 13 weeks’ gestation. Of the 324 respondents, 62 percent indicated that it was easy to not participate in abortion training (Jackson and Foster, 2012).

Kenneth J. Ryan Residency Training Program

The Ryan Program, developed by the UCSF Bixby Center in 1999, aims to integrate and enhance family planning training for OB/GYN residents in the United States and Canada (Ryan Residency Training Program, 2017a). The program offers resources and technical expertise to OB/GYN departments that wish to establish a formal, opt-out rotation in family planning (Ryan Residency Training Program, 2017a). Among the total 269 accredited OB/GYN residency programs across the United States during the 2016–2017 academic year, there are 90 Ryan programs6 (see Figure 3-1), and as of December 2016, 3,963 residents had graduated from Ryan programs (ACGME, 2017c; Ryan Residency Training Program, 2017b).

The Ryan curriculum consists of published comprehensive didactic learning modules and expected milestones for all aspects of abortion care, including contraceptive counseling (Ryan Residency Training Program, 2017c). These milestones distinguish among the necessary clinical competencies for residents-in-training, graduating residents, and area experts. Graduating residents must independently perform procedures (first-trimester aspiration and basic second-trimester D&E) and manage medication abortions and labor induction terminations; manage complications of the different types of abortion procedures; and determine the need for consultation, referral, or transfer of patients with complex conditions, such as those with medical comorbidities or prior uterine surgery.

In annual reviews of the Ryan Program, residents and program directors have reported significant exposure to all methods of abortion and contraception provision, as well as such broader gynecological skills as anesthesia and analgesia, uterine sizing, assessment of gestation, ultrasound, management of fetal demise, and management of abortion-related complications (Steinauer et al., 2013b). In a study by Steinauer and colleagues (2013a), most residents and program directors reported believing that both full and partial program participation improved residents’ knowledge and skills in counseling, contraception provision, and uterine evacuation for indications other than elective abortion, such as therapeutic abortion, miscarriage, and suspected ectopic management.

Fellowship in Family Planning

Other training opportunities include the Fellowship in Family Planning, a 2-year postresidency fellowship program that offers comprehensive training in research, teaching, and clinical practice in abortion and contraception

___________________

6 Personal communication, U. Landy, Ph.D., UCSF Bixby Center for Global Reproductive Health, March 30, 2017.

NOTE: RHEDI = Reproductive Health Education in Family Medicine.

SOURCES: FFP, 2017; RHEDI, 2017; Ryan Residency Training Program, 2017b.

at academic medical centers. The fellowship is offered at 30 university locations (see Figure 3-1) and is available to OB/GYNs who have completed residency training (FFP, 2017). Currently, 64 fellows are enrolled in these 2-year programs, and 275 physicians have completed the fellowship training (FFP, 2017).

Family Medicine

Women’s reproductive health care is a fundamental component of family medicine. Family physicians provide routine gynecological, pregnancy counseling, obstetrics, and contraceptive services (Brahmi et al., 2007; Dehlendorf et al., 2007; Goodman et al., 2013; Herbitter et al., 2011; Rubin et al., 2011). ACGME requires that family medicine trainees have 100 hours (or 1 month) or 125 patient encounters in gynecological care, including family planning, miscarriage management, contraceptive services, and options counseling for unintended pregnancy (ACGME, 2017a). The

Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM) Group on Hospital and Procedural Training recommends that all family medicine residents be exposed to uterine aspirations and D&Cs and have the opportunity to train to independent performance as these procedures are used for a variety of gynecological conditions (Nothnagle et al., 2008). Thus, although there is no specific abortion training requirement in family medicine, residents learn many gynecological skills that are applicable to performing abortions (e.g., counseling, aspirations, endometrial biopsies, and intrauterine device insertion and removal) (AAFP, 2016; Lyus et al., 2009). Indeed, the American Academy of Family Physicians considers medication and aspiration abortions to be within the scope of family medicine (AAFP, 2016).

Available data indicate that most family physicians do not provide abortions. A 2012 survey of 1,198 responding academic family medicine physicians found that only 15.3 percent of respondents had ever provided an abortion (medical or surgical) outside of training, and of those, only 33.8 percent had performed an abortion in the previous year (Herbitter et al., 2013). According to the most recent data collected from NAF members, 21 percent of NAF member providers who performed aspiration abortions in 2001 specialized in family practice (O’Connell et al., 2009). The 2016 National Graduate Survey, conducted by the American Board of Family Medicine and the Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors, was administered to 2013 graduates of residency training. When asked about specific subject areas and procedures, 17 percent of respondents (n = 2,060) reported that residency had prepared them in uterine aspiration/D&C, and 4 percent of respondents (n = 2,034) reported currently practicing these procedures.7

Most family medicine programs do not offer specific training in abortion, and only a small proportion of family physicians report having had access to abortion training (Herbitter et al., 2011, 2013; Lesnewski et al., 2003; Steinauer et al., 1997; Talley and Bergus, 1996). In a 2007–2008 survey of family medicine chief residents and program directors, almost two-thirds (63.9 percent) of residents reported that training in medication and aspiration abortions was not available in their programs (Herbitter et al., 2011).

The total number of family medicine residencies offering abortion training is unknown, although it is clear that access to such training varies markedly across the country (Herbitter et al., 2011; Steinauer et al., 1997; Talley et al., 1996). Programs in the West and Northeast are far more likely to provide abortion training relative to programs in the Midwest and South (Herbitter et al., 2011). In 2002, the STFM Group on Abortion Training

___________________

7 Personal communication, L. Peterson, M.D., Ph.D., American Board of Family Medicine, January 30, 2018.

and Access conducted a survey of family medicine residency programs to determine the levels of abortion training offered. They confirmed that only 3.3 percent (11 of 337) of responding programs offered fully integrated abortion training (Lesnewski et al., 2003). In programs where abortion training is available, it appears that curricula are quite variable. A 2004–2005 study of nine programs that required abortion training found that all nine provided training in vacuum aspiration, eight of the nine provided training in medication abortion, and eight of the nine offered ultrasound training (Brahmi et al., 2007). The clinical setting, duration, and content of nonprocedural training were not consistent across the nine programs (Brahmi et al., 2007).

In addition to the RHEDI programs discussed below, seven family medicine residency programs offer integrated and comprehensive abortion training, and two programs offer established local electives in abortion training (RHEDI, 2017) (see Figure 3-1).

RHEDI

The RHEDI program includes 26 family medicine residency programs with fully integrated abortion and family planning training—5.2 percent of the total 498 accredited family medicine residency programs in 2016 (ACGME, 2016; RHEDI, 2017; Summit and Gold, 2017) (see Figure 3-1). RHEDI, established in 2004 at the Montefiore Medical Center, provides grant funding and technical assistance to establish RHEDI programs in family medicine residencies throughout the United States. In a 2012–2014 evaluation of 214 residents in 12 RHEDI programs (representing 90 percent of residents who were part of a RHEDI program during the time period), residents reported increased exposure to provision of contraception (all methods), counseling on pregnancy options, counseling on abortion methods, ultrasound, aspiration and medication abortions, and miscarriage management after their RHEDI rotation. Self-rated competency had also improved (Summit and Gold, 2017). RHEDI is in the process of developing a standardized curriculum.8

Fellowship in Family Planning

The previously mentioned Fellowships in Family Planning are available to family physicians that have completed residency training. Three of the 30 fellowship sites (see Figure 3-1) are housed in departments of family

___________________

8 Personal communication, M. Gold, M.D., Albert Einstein College of Medicine, June 27, 2017.

medicine (FFP, 2017). Additionally, 2 of the 84 Ryan Residency Training programs are available to family physicians.9

Advanced Practice Clinicians

State licensing boards govern the scope of practice for APCs. CNMs and NPs are first credentialed as registered nurses and then as advanced practice nurses in a CNM or NP role. APCs may be educated and also credentialed to practice with a specific population (e.g., primary care, women’s health) and/or a specialty area (e.g., abortion care) (Taylor et al., 2009).

Professional regulation and credentialing are based on a set of essential elements that align government authority with regulatory and professional responsibilities. The latter include essential documents developed by the profession that provide a basis for education and practice regulation; formal education from a degree or professional certification program; formal accreditation of educational programs; legal scope of practice by state law and regulations, including licensure; and individual certification formally recognizing the knowledge, skills, and experience of the individual to meet the standards the profession has identified (Taylor et al., 2009).

Foster and colleagues (2006) conducted a survey of all 486 accredited NP, PA, and CNM programs in the United States, with a response rate of 42 percent (n = 202). Overall, 53 percent of responding programs (108 programs) reported didactic instruction in surgical abortion,10 MVA, and/or medication abortion; 21 percent (43 programs) reported providing clinical instruction in at least one of the three abortion procedures (Foster et al., 2006).

Abortion care competencies are operationalized within individual APC educational programs. In the Foster et al. (2006) study, among all APC educational programs, accredited CNM programs reported the highest rates of didactic instruction in abortion, and accredited NP programs reported the lowest rates of didactic and clinical instruction. Training in abortion care is very difficult for APCs to access. Planned Parenthood Federation of America’s Consortium of Abortion Providers offers some training to the federation’s members. NAF offers some didactic and practicum training in abortion care, as well as accredited continuing medical education, that is available to APCs (Taylor et al., 2009). Additionally, the Midwest Access Project (MAP) provides connection to training sites for APCs, although MDs receive priority in its placements (MAP, 2017).

___________________

9 Personal communication, U. Landy, Ph.D., UCSF Bixby Center for Global Reproductive Health, March 30, 2017.

10 The authors note a preference for the term “electric vacuum aspiration” to clarify “surgical abortion” in future surveys.

Certified Nurse-Midwives (CNMs)

Midwifery practice encompasses the full range of women’s primary care services, including primary care; family planning; STI treatment; gynecological services; care during pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum; and newborn care (ACNM, 2011a).

CNMs are prepared at the graduate level in educational programs accredited by the Accreditation Commission for Midwifery Education, and must pass a national certification examination administered by the American Midwifery Certification Board. The competencies and standards for the practice of midwifery in the United States are consistent with or exceed the global competencies and standards set forth by the International Confederation of Midwives, including, for example, uterine evacuation via MVA (ICM, 2011a, 2013). These competencies are outlined in Core Competencies for Basic Midwifery Practice and must be met by an individual graduating from an accredited midwifery program (ACNM, 2012).

While abortion care is not specifically identified as a core competency for basic midwifery practice, CNMs have the essential skills to be trained to provide medication and aspiration abortions. The scope of midwifery practice may be expanded beyond the core competencies to incorporate additional skills and procedures, such as aspiration abortion, by following the guidelines outlined in Standard VIII of Standards for the Practice of Midwifery (ACNM, 2011c).

Nurse Practitioners (NPs)

NPs receive advanced education (typically a master’s degree or clinical doctorate) and extensive clinical training to enable them to diagnose and manage patient care for a multitude of acute and chronic illnesses. They are independently licensed, have prescriptive authority in some form in all states, and work collaboratively with other health care professionals (Taylor et al., 2009). Their competencies are outlined in Nurse Practitioner Core Competencies, issued by the National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculties (NONPF, 2017).

The Consensus Model for APRN Regulation provides for the expansion of all NP and nurse-midwifery practice roles to advance their practice beyond the core competencies, providing flexibility to meet the emerging and changing needs of patients (APRN and NCSBN, 2008). Competency can be acquired through practical, supervised experience or through additional education and assessed in multiple ways through professional credentialing mechanisms.

Physician Assistants (PAs)

PA training programs are accredited by the Accreditation Review Commission on Education for the Physician Assistant (ARC-PA). There is no mandated specific curriculum for PA schools, nor is there mandated abortion or family planning training for PAs. The ARC-PA Practice Standards include supervised clinical training in women’s health (to include prenatal and gynecological care) (ARC-PA, 2010). The National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants prepares and administers certifying and recertifying examinations for PAs. The 2015 Content Blueprint includes abortion in its list of reproductive system diseases for the examinations. The Association of Physician Assistants in Obstetrics & Gynecology (APAOG) highlights two OB/GYN residencies, but these residencies do not offer specific abortion training, and most PAs are trained privately in abortion procedures by supervising physicians at their practice sites (APAOG, 2017).

Expansion of the scope of practice for PAs varies slightly from that for advanced practice nurses. Most state laws governing the scope of practice for PAs allow for broad delegatory authority by the supervising physician. The American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) recommends that all PAs consider four parameters when incorporating new skills into their practice: state law, facility policies, delegatory decisions made by the supervising physician, and the PA’s education and experience (AAPA, 2017).

AVAILABILITY OF TRAINED CLINICIANS

The safety and quality of abortion services are contingent on the availability of skilled providers. A number of issues influence the availability of providers skilled in abortion services, including the declining number of facilities offering services (discussed in Chapter 1), the geographic maldistribution of providers, and legal restrictions on training in and provision of services.

Geographic Distribution

There are marked geographic disparities in a woman’s ability to access abortion services in the United States, mirroring the locations of fellowship and residency programs in family planning. Abortion providers tend to be concentrated in urban areas, and a paucity of abortion providers exists in the South and Midwest, creating geographic barriers for women seeking abortion services in these regions (Johns et al., 2017; Jones and Jerman, 2017a; Paul and Norton, 2016). In 2011, 53 percent of women in the Midwest and 49 percent of women in the South lived in a county without an abortion clinic, compared with 24 percent of women in the Northeast and 16 percent in the West (Jones and Jerman, 2014). In 2008, women

traveled an average of 30 miles for an abortion, with 17 percent traveling more than 50 miles (Jones and Jerman, 2013). Among women living in rural areas, 31 percent traveled more than 100 miles to have an abortion (Jones and Jerman, 2013).

A significant amount of qualitative and quantitative research has been conducted to evaluate the impact of a 2013 law (H.B. 2)11 that resulted in a reduced number of abortion facilities in Texas. The law went into effect in November 2013, and the number of Texas clinics subsequently declined from 41 in May 2013 to 17 in June 2016 (Grossman et al., 2014, 2017).

Researchers compared the 6-month periods before and after the implementation of the law and found that in the 6 months after implementation, the abortion rate decreased by 13 percent, the proportion of abortions at or after 12 weeks’ gestation increased, and medication abortion decreased by 70 percent (Grossman et al., 2014). Furthermore, women had to travel an increased distance for abortion care. The number of women of reproductive age living more than 200 miles from an abortion facility increased from approximately 10,000 in the 6 months prior to the law’s implementation to 290,000 6 months after implementation. The number of women living more than 50 and 100 miles from a facility increased from approximately 800,000 to 1.7 million and 400,000 to nearly 1.1 million, respectively (Grossman et al., 2014). Gerdts and colleagues (2016) surveyed women seeking abortion care in 2014 and found that those whose nearest clinic closed in 2013 traveled on average 85 miles to obtain care, compared with 22 miles traveled by women whose nearest clinic remained open. A later study by Grossman and colleagues (2017) found that the decline in abortions increased as the distance to the nearest facility increased between 2012 and 2014. Counties with no change in distance to a facility saw a 1.3 percent decline in abortions, whereas counties with an increase in distance of 100 miles or more saw a 50.3 percent decline (Grossman et al., 2017). Women reported increased informational, cost, and logistical barriers to obtaining abortion services; increased cost and travel time; and a frustrated demand for medication abortion after the law took effect (Baum et al., 2016; Fuentes et al., 2016; Gerdts et al., 2016).

Geographic location figures prominently in equitable access to abortion providers, impacting both the quality and safety of abortion care for women. A 2011–2012 study of claims data on 39,747 abortions covered by California’s state Medicaid program (named Medi-Cal) found that

___________________

11 Texas House Bill 2 (Tex. Health & Safety Code Ann. § 171.0031[a] [West Cum. Supp. 2015]) banned abortions after 20 weeks postfertilization, required physicians performing abortions to have hospital admitting privileges within 30 miles of the abortion facility, required the provision of medication abortion to follow the labeling approved by the FDA, and required all abortion facilities to be ambulatory surgery centers (Grossman et al., 2014).

12 percent of the women traveled 50 miles or more for abortion services, and 4 percent traveled more than 100 miles (Upadhyay et al., 2017). For most patients in this study, greater distance traveled was associated with an increased likelihood of seeking follow-up care at a local emergency department, driving up cost and interrupting continuity of care. Women traveling longer distances (25–49 miles, 50–99 miles, or 100 miles or more) were significantly more likely than those traveling 25 miles or less to seek follow-up care in a local emergency department instead of returning to their original provider (Upadhyay et al., 2017). Costs associated with emergency department care were consistently higher than those of follow-up care at the abortion site. In addition to disrupting continuity of care and increasing medical costs, emergency department visits are not the ideal avenue for follow-up abortion care. Evidence suggests that abortion providers are better prepared than emergency department staff to evaluate women postabortion, avoiding unnecessary use of such interventions as repeat aspiration or antibiotics (Beckman et al., 2002). This finding suggests a disparity in quality of abortion care for women unable to return to their abortion site for follow-up.

As demonstrated in Texas after passage of H.B. 2, geographic disparities contribute to increased travel and logistic challenges for women seeking abortion care, which in turn can result in delays (Bessett et al., 2011; Drey et al., 2006; Finer et al., 2006; Foster and Kimport, 2013; French et al., 2016; Fuentes et al., 2016; Janiak et al., 2014; Kiley et al., 2010; Roberts et al., 2014; Upadhyay et al., 2014; White et al., 2016). Restrictive regulations, including mandatory waiting periods that require a woman to make multiple trips to the abortion facility, impact the timeliness of obtaining abortion care (Grossman et al., 2014; Jones and Jerman, 2016). These challenges are especially burdensome for poor women, women traveling long distances for care, and those with the fewest resources (Baum et al., 2016; Finer et al., 2006; Fuentes et al., 2016; Ostrach and Cheyney, 2014). Delays in obtaining care may result in later abortions, requiring procedures with greater clinical risks and increased costs, in addition to limiting patient options regarding abortion procedures and pain management.

As noted in Chapter 1, most women pay out of pocket for abortions (Jones and Jerman, 2017b). A 2012 survey of nonhospital abortion facilities estimated that at 10 weeks’ gestation, the average charge for an aspiration abortion was $480 and for a medication abortion was $504 (Jerman and Jones, 2014). The median charge for an abortion at 20 weeks’ gestation was $1,350.

The availability of providers also varies by gestation. Far fewer clinicians offer abortions at later gestation. In 2012, 95 percent of facilities offered abortions at 8 weeks’ gestation, 72 percent at 12 weeks’, 34 percent at 20 weeks’, and 16 percent at 24 weeks’ (Jerman and Jones, 2014).

According to Guttmacher’s analysis, there is a sharp decline in abortion provision by nonspecialized clinics and physician’s offices after 9 weeks’ gestation, suggesting that these facilities are more likely to offer only early abortion services (Jerman and Jones, 2014).

Regulations That Affect Availability

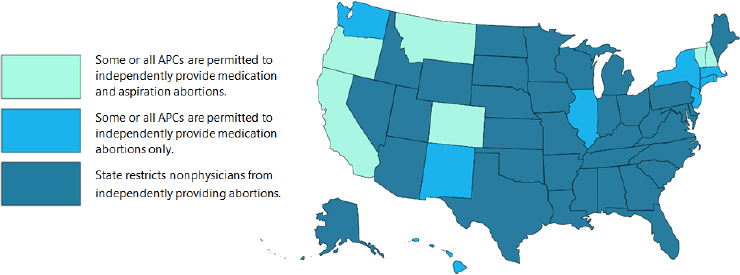

In many states, abortion-specific regulations address provider education and training and the type of clinician that is permitted to provide abortion services. Many states have regulations limiting the scope of practice for APCs and excluding nonphysician providers from performing abortions (ACOG, 2014a,b; Guttmacher Institute, 2017a; O’Connell et al., 2009). In 15 states plus the District of Columbia (DC), APCs may provide medication abortions, and in 6 of those states plus DC, APCs are also permitted to perform aspiration abortions independently (Guttmacher Institute, 2017a; RHN, 2017). However, 35 states require all abortions (including medication and aspiration abortions) to be performed by a licensed physician (see Figure 3-2).

Twenty states require the involvement of a second physician if an abortion is performed after a specified gestation, typically after 22 weeks since the last menstrual period or later in the pregnancy (Guttmacher Institute, 2017b). No clinical guidelines suggest that D&E and induction abortions require the involvement of a second physician (ACOG, 2015; NAF, 2017; RCOG, 2011, 2015; SFP, 2011, 2013; WHO, 2014). One state requires the provider be either a board-certified OB/GYN or eligible for certification (Guttmacher Institute, 2017c). In one state, only an OB/GYN is permitted

NOTE: APC = advanced practice clinician.

SOURCE: Adapted from RHN, 2017. Created by Samantha Andrews. Used with permission.

to provide abortions after 14 weeks’ gestation (Guttmacher Institute, 2017c). By establishing higher-level credentials than are necessary based on the clinical competencies identified earlier in this chapter, these policies can reduce the availability of providers, resulting in inequitable access to abortion care based on a woman’s geography. In addition, these policies can limit patients’ preferences, as patient choice is contingent on the availability of trained and experienced providers (ACOG, 2015). Limiting choices impacts patient-centered care, and also negatively affects the efficiency of abortion services by potentially increasing the costs of abortion care as the result of requiring the involvement of a physician to perform a procedure that can be provided safely and effectively by an APC.

Abortion-specific regulations limit training opportunities in many states. Twelve states have laws that specifically prohibit the provision of abortion services in public institutions, such as state-run hospitals or health systems.12 This type of restriction precludes training in those sites and can make it challenging for educational programs located in those facilities to comply with the abortion-related training requirements stipulated by academic credentialing organizations discussed earlier.

SUMMARY

This chapter has addressed several questions regarding the competencies and training of the clinical workforce that performs abortions in the United States. The committee found that abortion care, in general, requires providers skilled in patient preparation (education, counseling, and informed consent); clinical assessment (confirming intrauterine pregnancy, determining gestation, taking a relevant medical history, and physical examination); pain management; identification and management of side effects and serious complications; and contraceptive counseling and provision. To provide medication abortions, the clinician should be skilled in all these areas. To provide aspiration abortions, the clinician should also be skilled in the technical aspects of an aspiration procedure. To provide D&E abortions, the clinician needs the relevant surgical expertise and sufficient caseload to maintain the requisite surgical skills. To provide induction abortions, the clinician requires the skills needed for managing labor and delivery.

Both physicians (typically OB/GYNs and family medicine physicians, but other physicians can be trained) and APCs can provide medication

___________________

12 Personal communication, O. Cappello, Guttmacher Institute, August 4, 2017: AZ § 15-1630, GA § 20-2-773; KS § 65-6733 and § 76-3308; KY § 311.800; LA RS § 40:1299 and RS § 4 0.1061; MO § 188.210 and § 188.215; MS § 41-41-91; ND § 14-02.3-04; OH § 5101.57; OK 63 § 1-741.1; PA 18 § 3215; TX § 285.202.

and aspiration abortions safely and effectively. Many states, however, prohibit nonphysicians from performing abortions regardless of the method. OB/GYNs, family medicine physicians, and other physicians with appropriate training and experience can provide D&E abortions. The committee did not find research assessing the ability of APCs, given the appropriate training, to perform D&Es safely and effectively. Induction abortions can be provided by clinicians (OB/GYNs, family medicine physicians, and CNMs) with training in managing labor and delivery.

Access to clinical education and training in abortion care in the United States is highly variable at both the undergraduate and graduate levels. Medical residents and other advanced clinical trainees often have to find abortion training and experience in settings outside of their educational program. Training opportunities are particularly limited in the Southern and Midwestern states, as well as in rural areas throughout the country.

REFERENCES

AAFP (American Academy of Family Physicians). 2016. Recommended curriculum guidelines for family medicine residents: Women’s health and gynecologic care. AAFP reprint no. 282. http://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/medical_education_residency/program_directors/Reprint282_Women.pdf (accessed October 19, 2017).

AAPA (American Academy of Physician Assistants). 2017. PA: Scope of practice. AAPA issue brief. https://www.aapa.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Issue-brief_Scope-of-Practice_0117-1.pdf (accessed October 11, 2017).

ACGME (Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education). 2016. Number of accredited programs academic year 2015–2016, United States. https://apps.acgme.org/ads/Public/Reports/ReportRun?ReportId=3&CurrentYear=2016&AcademicYearId=2015 (accessed February 12, 2018).

ACGME. 2017a. ACGME program requirements for graduate medical education in family medicine. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/120_family_medicine_2017-07-01.pdf?ver=2017-06-30-083354-350 (accessed December 7, 2017).

ACGME. 2017b. ACGME program requirements for graduate medical education in obstetrics and gynecology. http://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/220_obstetrics_and_gynecology_2017-07-01.pdf (accessed October 19, 2017).

ACGME. 2017c. Number of accredited programs academic year 2016–2017, United States. https://apps.acgme.org/ads/Public/Reports/ReportRun?ReportId=3&CurrentYear=2017&AcademicYearId=2016 (accessed January 5, 2018).

ACNM (American College of Nurse-Midwives). 2011a. Definition of midwifery and scope of practice of certified nurse-midwives and certified midwives. http://www.midwife.org/ACNM/files/ACNMLibraryData/UPLOADFILENAME/000000000266/Definition%20of%20Midwifery%20and%20Scope%20of%20Practice%20of%20CNMs%20and%20CMs%20Feb%202012.pdf (accessed October 11, 2017).

ACNM. 2011b. Position statement: Reproductive health choices. http://midwife.org/ACNM/files/ACNMLibraryData/UPLOADFILENAME/000000000087/Reproductive_Choices.pdf (accessed February 11, 2018).

ACNM. 2011c. Standards for the practice of midwifery. http://www.midwife.org/ACNM/files/ACNMLibraryData/UPLOADFILENAME/000000000051/Standards_for_Practice_of_Midwifery_Sept_2011.pdf (accessed October 11, 2017).

ACNM. 2012. Core competencies for basic midwifery practice. http://www.midwife.org/ACNM/files/ACNMLibraryData/UPLOADFILENAME/000000000050/Core%20Comptencies%20Dec%202012.pdf (accessed October 11, 2017).

ACOG (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists). 2014a. Committee opinion no. 612: Abortion training and education. Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women. http://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Health-Care-for-Underserved-Women/Abortion-Training-and-Education (accessed October 16, 2017).

ACOG. 2014b. Committee opinion no. 613: Increasing access to abortion. Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women. https://www.acog.org/-/media/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Health-Care-for-Underserved-Women/co613.pdf?dmc=1&ts=20171011T2045552523 (accessed October 16, 2017).

ACOG. 2015. Practice bulletin no. 135: Second-trimester abortion. Obstetrics & Gynecology 121(6):1394–1406.

ACOG and SFP (Society for Family Planning). 2014. Practice bulletin no. 143: Medical management of first-trimester abortion. Obstetrics & Gynecology 123(3):676–692.

Allen, R. H., and A. B. Goldberg. 2016. Cervical dilation before first-trimester surgical abortion (<14 weeks’ gestation). Contraception 93(4):277–291.

Almeling, R., L. Tews, and S. Dudley. 2000. Abortion training in U.S. obstetrics and gynecology residency programs, 1998. Family Planning Perspectives 32(6):268–271, 320.

ANSIRH (Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health). 2014. HWPP #171 final data update. ANSIRH, Health Workforce Pilot Project, June. https://www.ansirh.org/sites/default/files/documents/hwppupdate-june2014.pdf (accessed February 13, 2018).

APAOG (Association of Physician Assistants in Obstetrics and Gynecology). 2017. OBGYN residency. http://www.paobgyn.org/residency (accessed October 20, 2017).

APHA (American Public Health Association). 2011. Provision of abortion care by advanced practice nurses and physician assistants. https://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2014/07/28/16/00/provision-of-abortion-care-by-advanced-practice-nurses-and-physician-assistants (accessed October 20, 2017).

APRN (Advanced Practice Registered Nurses) and NCSBN (National Council of State Boards of Nursing). 2008. Consensus model for APRN regulation: Licensure, accreditation, certification and education. Chicago, IL: National Council of State Boards of Nursing. https://www.ncsbn.org/Consensus_Model_for_APRN_Regulation_July_2008.pdf (accessed October 11, 2017).

ARC-PA (Accreditation Review Commission on Education for the Physician Assistant). 2010. Accreditation standards for physician assistant education, 4th ed. Johns Creek, GA: ARC-PA. http://paeaonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/12b-ARC-PA-Standards.pdf (accessed October 20, 2017).

Baird, T. L., L. D. Castleman, A. G. Hyman, R. E. Gringle, and P. D. Blumenthal. 2007. Clinician’s guide for second-trimester abortion, 2nd ed. Chapel Hill, NC: Ipas.

Baker, A., and T. Beresford. 2009. Informed consent, patient education, and counseling. In Management of unintended and abnormal pregnancy, 1st ed., edited by M. Paul, E. S. Lichtenberg, L. Borgatta, D. A. Grimes, P. G. Stubblefield, and M. D. Creinin. Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell Publishing. Pp. 48–62.

Barnard, S., C. Kim, M. H. Park, and T. D. Ngo. 2015. Doctors or mid-level providers for abortion. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews 27(7):CD011242.

Baum, S. E., K. White, K. Hopkins, J. E. Potter, and D. Grossman. 2016. Women’s experience obtaining abortion care in Texas after implementation of restrictive abortion laws: A qualitative study. PLoS One 11(10):e0165048.

Beckman, L. J., S. M. Harvey, and S. J. Satre. 2002. The delivery of medical abortion services: The views of experienced providers. Women’s Health Issues 12(2):103–112.

Bennett, I. M., M. Baylson, K. Kalkstein, G. Gillespie, S. L. Bellamy, and J. Fleischman. 2009. Early abortion in family medicine: Clinical outcomes. Annals of Family Medicine 7(6):527–533.

Bessett, D., K. Gorski, D. Jinadasa, M. Ostrow, and M. J. Peterson. 2011. Out of time and out of pocket: Experiences of women seeking state-subsidized insurance for abortion care in Massachusetts. Women’s Health Issues 21(3 Suppl.):S21–S25.

Brahmi, D., C. Dehlendorf, D. Engel, K. Grumbach, C. Joffe, and M. Gold. 2007. A descriptive analysis of abortion training in family medicine residency programs. Family Medicine 39(6):399–403.

Creinin, M. D., and K. G. Danielsson. 2009. Medical abortion in early pregnancy. In Management of unintended and abnormal pregnancy, 1st ed., edited by M. Paul, E. S. Lichtenberg, L. Borgatta, D. A. Grimes, P. G. Stubblefield, and M. D. Creinin. Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell Publishing. Pp. 111–134.

Davis, A., and T. Easterling. 2009. Medical evaluation and management. In Management of unintended and abnormal pregnancy, 1st ed., edited by M. Paul, E. S. Lichtenberg, L. Borgatta, D. A. Grimes, P. G. Stubblefield, and M. D. Creinin. Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell Publishing. Pp. 78–79.

Dehlendorf, C., D. Brahmi, D. Engel, K. Grumbach, C. Joffe, and M. Gold. 2007. Integrating abortion training into family medicine residency programs. Family Medicine 39(5):337–342.

Drey, E. A., D. G. Foster, R. A. Jackson, S. J. Lee, L. H. Cardenas, and P. D. Darney. 2006. Risk factors associated with presenting for abortion in the second trimester. Obstetrics & Gynecology 107(1):128–135.

Eastwood, K. L., J. E. Kacmar, J. Steinauer, S. Weitzen, and L. A. Boardman. 2006. Abortion training in United States obstetrics and gynecology residency programs. Obstetrics & Gynecology 108(2):303–308.

FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration). 2016. Highlights of prescribing information: Mifeprex® (revised 3/2016). https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/020687s020lbl.pdf (accessed October 20, 2017).

FFP (Fellowship in Family Planning). 2017. Where are the fellowships located? https://www.familyplanningfellowship.org/fellowship-programs (accessed October 20, 2017).

Finer, L. B., L. F. Frohwirth, L. A. Dauphinee, S. Singh, and A. M. Moore. 2006. Timing of steps and reasons for delays in obtaining abortions in the United States. Contraception 74(4):334–344.

Foster, A. M., P. Chelsea, M. K. Allee, K. Simmonds, M. Zurek, and A. Brown. 2006. Abortion education in nurse practitioner, physician assistant and certified nurse-midwifery programs: A national survey. Contraception 73(4):408–414.

Foster, D. G., and K. Kimport. 2013. Who seeks abortions at or after 20 weeks? Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 45(4):210–218.

Freedman, L. R., and D. B. Stulberg. 2013. Conflicts in care for obstetric complications in Catholic hospitals. AJOB Primary Research 4(4):1–10.

Freedman, L. R., U. Landy, and J. Steinauer. 2008. When there’s a heartbeat: Miscarriage management in Catholic-owned hospitals. American Journal of Public Health 98(10):1774–1778.

French, V., R. Anthony, C. Souder, C. Geistkemper, E. Drey, and J. Steinauer. 2016. Influence of clinician referral on Nebraska women’s decision-to-abortion time. Contraception 93(3):236–243.

Fuentes, L., S. Lebenkoff, K. White, C. Gerdts, K. Hopkins, J. E. Potter, and D. Grossman. 2016. Women’s experiences seeking abortion care shortly after the closure of clinics due to a restrictive law in Texas. Contraception 93(4):292–297.

Gavin, L., S. Moskosky, M. Carter, K. Curtis, E. Glass, E. Godfrey, A. Marcell, N. Mautone-Smith, K. Pazol, N. Tepper, and L. Zapata. 2014. Providing quality family planning services: Recommendations of CDC and the U.S. Office of Population Affairs. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports 63(RR04):1–29. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr6304a1.htm (accessed September 15, 2017).

Gemzell-Danielsson, K., and S. Lalitkumar. 2008. Second trimester medical abortion with mifepristone-misoprostol and misoprostol alone: A review of methods and management. Reproductive Health Matters 16(31 Suppl.):162–172.

Gerdts, C., L. Fuentes, D. Grossman, K. White, B. Keefe-Oates, S. E. Baum, K. Hopkins, C. W. Stolp, and J. E. Potter. 2016. Impact of clinic closures on women obtaining abortion services after implementation of a restrictive law in Texas. American Journal of Public Health 106(5):857–864.

Goldman, M. B., J. S. Occhiuto, L. E. Peterson, J. G. Zapka, and R. H. Palmer. 2004. Physician assistants as providers of surgically induced abortion services. American Journal of Public Health 94(8):1352–1357.

Goldstein, S. R., and M. F. Reeves. 2009. Clinical assessment and ultrasound in early pregnancy. In Management of unintended and abnormal pregnancy, 1st ed., edited by M. Paul, E. S. Lichtenberg, L. Borgatta, D. A. Grimes, P. G. Stubblefield, and M. D. Creinin. Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell Publishing. Pp. 63–77.

Goodman, S., G. Shih, M. Hawkins, S. Feierabend, P. Lossy, N. J. Waxman, M. Gold, and C. Dehlendorf. 2013. A long-term evaluation of a required reproductive health training rotation with opt-out provisions for family medicine residents. Family Medicine 45(3):180–186.

Goodman, S., G. Flaxman, and TEACH Trainers Collaborative Working Group. 2016. Teach early abortion training workbook, 5th ed. San Francisco, CA: UCSF Bixby Center for Global Reproductive Health. http://www.teachtraining.org/training-tools/early-abortion-training-workbook (accessed October 20, 2017).

Grossman, D., K. Blanchard, and P. Blumenthal. 2008. Complications after second trimester surgical and medical abortion. Reproductive Health Matters 16(31 Suppl.):173–182.

Grossman, D., S. Baum, L. Fuentes, K. White, K. Hopkins, A. Stevenson, and J. E. Potter. 2014. Change in abortion services after implementation of a restrictive law in Texas. Contraception 90(5):496–501.

Grossman, D., K. White, K. Hopkins, and J. E. Potter. 2017. Change in distance to nearest facility and abortion in Texas, 2012 to 2014. Journal of the American Medical Association 317(4):437–438.

Guttmacher Institute. 2017a. An overview of abortion laws. Washington, DC: Guttmacher Institute. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/overview-abortion-laws (accessed October 20, 2017).

Guttmacher Institute. 2017b. State policies on later abortions. Washington, DC: Guttmacher Institute. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/state-policies-later-abortions (accessed September 21, 2017).

Guttmacher Institute. 2017c. Targeted regulation of abortion providers. Washington, DC: Guttmacher Institute. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/targeted-regulation-abortion-providers (accessed June 23, 2017).

Hammond, C., and S. Chasen. 2009. Dilation and evacuation. In Management of unintended and abnormal pregnancy, 1st ed., edited by M. Paul, E. S. Lichtenberg, L. Borgatta, D. A. Grimes, P. G. Stubblefield, and M. D. Creinin. Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell Publishing. Pp. 157–177.

Health IT. 2013. Shared decision making. https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/nlc_shared_decision_making_fact_sheet.pdf (accessed January 10, 2018).

Herbitter, C., M. Greenberg, J. Fletcher, C. Query, J. Dalby, and M. Gold. 2011. Family planning training in U.S. family medicine residencies. Family Medicine 43(8):574–581.

Herbitter, C., A. Bennett, D. Finn, D. Schubert, I. M. Bennett, and M. Gold. 2013. Management of early pregnancy failure and induced abortion by family medicine educators. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine 26(6):751–758.

Hern, W. M. 2016. Second-trimester surgical abortion. https://www.glowm.com/section_view/heading/Second-Trimester%20Surgical%20Abortion/item/441 (accessed October 6, 2017).

ICM (International Confederation of Midwives). 2011a. Global standards for midwifery regulation. The Hague, Netherlands: ICM. http://internationalmidwives.org/assets/uploads/documents/Global%20Standards%20Comptencies%20Tools/English/GLOBAL%20STANDARDS%20FOR%20MIDWIFERY%20REGULATION%20ENG.pdf (accessed October 20, 2017).

ICM. 2011b. Position statement: Midwives’ provision of abortion-related services. https://internationalmidwives.org/assets/uploads/documents/Position%20Statements%20-%20English/Reviewed%20PS%20in%202014/PS2008_011%20V2014%20Midwives’%20provision%20of%20abortion%20related%20services%20ENG.pdf (accessed February 11, 2018).

ICM. 2013. Essential competencies for basic midwifery practice, 2010 (revised 2013). The Hague, Netherlands: ICM. https://internationalmidwives.org/assets/uploads/documents/CoreDocuments/ICM%20Essential%20Competencies%20for%20Basic%20Midwifery%20Practice%202010,%20revised%202013.pdf (accessed February 12, 2018).

Jackson, C. B., and A. M. Foster. 2012. OB/GYN training in abortion care: Results from a national survey. Contraception 86(4):407–412.

Janiak, E., I. Kawachi, A. Goldberg, and B. Gottlieb. 2014. Abortion barriers and perceptions of gestational age among women seeking abortion care in the latter half of the second trimester. Contraception 89(4):322–327.

Jatlaoui, T. C., A. Ewing, M. G. Mandel, K. B. Simmons, D. B. Suchdev, D. J. Jamieson, and K. Pazol. 2016. Abortion surveillance—United States, 2013. MMWR Surveillance Summaries 65(SS-12):1–44.

Jerman, J., and R. K. Jones. 2014. Secondary measures of access to abortion services in the United States, 2011 and 2012: Gestational age limits, cost, and harassment. Women’s Health Issues 24(4):e419–e424.

Johns, N. E., D. G. Foster, and U. D. Upadhyay. 2017. Distance traveled for Medicaid-covered abortion care in California. BMC Health Services Research 17(287):1–11.

Jones, R. K., and J. Jerman. 2013. How far did U.S. women travel for abortion services in 2008? Journal of Women’s Health 22(8):706–713.

Jones, R. K., and J. Jerman. 2014. Abortion incidence and service availability in the United States, 2011. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 46(1):3–14.

Jones, R. K., and J. Jerman. 2016. Time to appointment and delays in accessing care among U.S. abortion patients. Washington, DC: Guttmacher Institute. https://www.guttmacher.org/report/delays-in-accessing-care-among-us-abortion-patients (accessed April 15, 2017).

Jones, R. K., and J. Jerman. 2017a. Abortion incidence and service availability in the United States, 2014. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 49(1):17–27.

Jones, R. K., and J. Jerman. 2017b. Characteristics and circumstances of U.S. women who obtain very early and second trimester abortions. PLoS One 12(1):e0169969.

Kapp, N., and H. von Hertzen. 2009. Medical methods to induce abortion in the second trimester. In Management of unintended and abnormal pregnancy, 1st ed., edited by M. Paul, E. S. Lichtenberg, L. Borgatta, D. A. Grimes, P. G. Stubblefield, and M. D. Creinin. Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell Publishing. Pp. 178–192.

Kiley, J. W., L. M. Yee, C. M. Niemi, J. M. Feinglass, and M. A. Simon. 2010. Delays in request for pregnancy termination: Comparison of patients in the first and second trimesters. Contraception 81(5):446–451.