5

Postcrash and Arrest Interventions

INTRODUCTION

While the two previous chapters discuss interventions aimed at influencing behaviors such as drinking to impairment and driving while impaired, this chapter focuses on reducing the likelihood or severity of negative outcomes of these behaviors: motor vehicle crashes and serious injuries and fatalities. As noted throughout the report, alcohol-impaired driving fatalities make up 28 percent of all traffic fatalities, and 10,497 people were killed in alcohol-impaired driving crashes in 2016. Because of data limitations, it can be difficult to obtain accurate arrest data on driving while impaired (DWI), accurate counts of how many offenders reoffend, and estimates of the number of DWI arrests that lead to a conviction (see Chapter 6 and Appendix A for more on data limitations). However, available data show that there were more than 1 million arrests for driving under the influence in 2015 (CDC, 2017; FBI, 2015). About 20 to 28 percent of first-time DWI offenders will repeat the offense (Lapham et al., 2006; Robertson et al., 2016), and recidivists are about 60 percent more likely to be involved in a fatal crash (Fell, 2014; Sloan et al., 2016).

This chapter begins with a section on the interventions (i.e., policies, systems, and programs) in the legal system that focus on deterring the general public (general deterrence) and those who have been previously arrested (specific deterrence) from driving while impaired. According to criminological theories, potential offenders balance risks and benefits when choosing whether to commit a crime (Nagin, 2013); deterrence theory relies on the perception of “swift, certain, and severe” detection

and punishment of criminal activity, including alcohol-impaired driving (Goodwin et al., 2015, p. 1-10; NIAAA, 2000; Nichols and Ross, 1989). This perception is built on a system of continued, publicized enforcement (IIHS, 2017a). This section also focuses on treatment of those convicted of alcohol-impaired driving to help modify their behaviors and decrease the likelihood that they will repeat the crime. There are many other points in the legal process that could be improved that are not discussed in this section. The interventions discussed are those the committee determined would have the greatest effect on the population, are feasible, are cost-effective, and target specific high-risk populations. The chapter’s second section includes information on how to improve emergency response after a motor vehicle crash, with a focus on rural areas. Although the committee did not focus on emergency response as an intervention, it is a promising area to help reduce fatalities in rural areas. As discussed in Chapter 2, rural areas are an important target population for alcohol-impaired driving because they account for a large proportion of fatal crashes, and many existing interventions are more relevant to urban areas. The interventions in this chapter engage the range of actors required to enforce laws and detect, prosecute, adjudicate, and treat alcohol-impaired drivers as well as respond to alcohol-impaired driving crashes.

LEGAL SYSTEM INTERVENTIONS: ENFORCEMENT

Law enforcement officers are trained to detect and arrest impaired drivers in three phases. The first phase is the law enforcement officer’s observation of the driver and any unsafe behaviors that draw the officer’s attention to the vehicle, such as lane swerving or failure to obey traffic signs and signals. After pulling over a potentially impaired driver, the second phase of detection involves the officer’s personal contact with the driver. Law enforcement officials are trained to use all senses when communicating with the driver. For example, the officer observes how the driver is speaking, any odors coming from the driver or vehicle, and any items visible in the vehicle. If the officer suspects the driver is impaired, he or she can then perform the third phase by requesting the driver to perform the standardized field sobriety tests (SFSTs). The officer will continue to observe the driver as he or she exits the vehicle, looking for additional indicators of impairment such as slurred speech or poor motor control. At this point the officer will also ask the driver if he or she has any medical conditions that would preclude the driver from performing the SFSTs. The SFSTs are made up of three validated parts: the walk and turn; the one-leg stand; and the horizontal gaze nystagmus (although some jurisdictions do not allow admission of testimony regarding the horizontal gaze nystagmus). In this phase, the officer may also administer

a preliminary, handheld breath test (PBT) (Voas and Fell, 2011). This device can be used to indicate the presence of alcohol, but the results cannot be used in court in most states. A drug recognition expert could also be summoned if the officer does not think alcohol is the sole cause of the driver’s impairment. Taken together, the observations of driving ability, communication with the driver, and performance on the SFSTs can lead an officer to conclude there is probable cause for arrest. Subsequent to arrest, officers will request the driver take a chemical test, such as a blood test, to determine blood alcohol concentration (BAC) (Voas and Fell, 2011). State laws vary with respect to policies criminalizing refusal to take chemical tests and license suspension at the point of arrest.

There are some barriers to the process of successfully detecting and arresting alcohol-impaired drivers. For example, law enforcement officers may not be adequately or consistently trained in the three phases or the agency might be understaffed. Additionally, some states have limited laboratories or personnel to complete tests, and tests are often expensive and resource intensive.

Furthermore, it is important to note that there is evidence of systematic discrimination and disproportionate targeting of people of color by the police in the United States (Aboelata et al., 2017; Ingraham, 2014; NASEM, 2017; President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing, 2015). Implementing a unified approach to reducing alcohol-impaired driving in communities would require intensive officer training and community engagement to foster cooperation and avoid alienating residents as communities and police work toward a common goal of zero lives lost (Aboelata et al., 2017).

Breath and Blood Tests for Detecting Alcohol Impairment

Once an officer arrests a driver, the officer will ask the driver to provide a breath test, which may take place at a roadside location or at a police station (Berning et al., 2008). A driver may decline to provide a breath test. The refusal may significantly affect or hinder subsequent prosecution and sanctions, as the absence of a BAC test result precludes a suspected alcohol-impaired driver from being charged under a per se law (Berning et al., 2008).1 Driver refusal rates for tests vary greatly among states. In 2011, the range of state breath test refusal rates (of Puerto Rico and 33 states with adequate reporting data) was 1 percent to 82 percent, with a national average of 24 percent. Two states (Florida and New Hampshire) had breath test refusal rates above 70 percent, and two more states had rates above 40 percent. Puerto Rico and 21 states had breath

___________________

1 A per se law means that the act in question is illegal in and of itself.

test refusal rates below 25 percent, and of those, 6 states and Puerto Rico had rates of 10 percent or less (Namuswe et al., 2014).

Toxicologists can use a calculation (retrograde extrapolation) to determine an impaired driver’s BAC at the time of an offense using, for example, a later BAC result obtained at the police station after arrest (AAA, 2016). This calculation factors in details such as the driver’s weight, height, sex, number and type of drinks consumed, and time passed to establish a metabolism rate and estimated BAC while the person was driving (APRI, 2003). As an estimate based on assumptions, results of retrograde extrapolation are not as accurate as a BAC measured in real time. Results can be used in expert testimony in court; however, they may be challenged or excluded, which can disadvantage a prosecutor’s case (APRI, 2003; Robertson and Simpson, 2002).

Testing Alcohol Impairment—Practices and Policies

All 50 states and the District of Columbia have implied consent laws, meaning that drivers using state roads (or federally owned park roads) have “consented” to comply with sobriety testing if there is an indication that they are driving while impaired. In an effort to compel drivers to comply with sobriety testing, states have enacted laws that make it a criminal offense to refuse a chemical test (e.g., Minnesota and Nebraska, among 16 other states)2 (Goodwin et al., 2015). As discussed above, law enforcement officials have few tests at their disposal to identify and detect alcohol-impaired drivers, and each of these tests—the SFSTs, a handheld breath-testing device, and blood or urine tests—come with their own limitations and challenges. While the SFSTs and handheld breath-testing devices can be administered at the point of contact with a driver who is suspected of being alcohol impaired, blood, breath, or urine testing are generally administered by trained technicians at a hospital or police station. Some jurisdictions have introduced enforcement vans with evidentiary equipment, although these can be costly and are not available everywhere (DeMetrick, 2016; Hedlund and McCartt, 2002; NC Health and Human Services, 2017). SFSTs and blood, breath, and urine tests can all be used to facilitate the prosecution of DWI cases, although the extent to which they can be admissible in court varies from state to state.

One challenge that police officers face when it comes to administering alcohol-impairment tests is the possibility that drivers simply refuse to comply with their request for testing. Unless the penalty for refusing a chemical test exceeds the penalty that a driver could incur should they fail the test (e.g., being prosecuted for impaired driving), there is little

___________________

2 Number as of 2013 (Goodwin et al., 2015).

incentive for drivers to comply. See Chapter 4 for more information about no refusal enforcement. Without court-admissible tests results, however, it is difficult for police officers or court officials to prove whether a driver was indeed alcohol impaired at the time he or she was stopped.

In 2016, the Supreme Court ruled on a case involving the admissibility of breath and blood tests in states where drivers were told they were subject to criminal charges if they refused to comply with a police officer’s request to take a sobriety test.3 The defendants argued that their Fourth Amendment rights had been violated because they could not refuse the tests, and were not served a court-ordered warrant for the test, thus constituting an unreasonable search. In their ruling, the court determined that the Fourth Amendment rights of drivers were not violated and no warrant was necessary since the breath tests were not invasive, the tests only measured alcohol in the breath, and no biosamples were stored after the test was administered. In regard to blood tests, however, the court ruled that a warrant would be necessary since the act of drawing blood is invasive, an individual’s blood can yield additional information beyond the BAC, and biosamples could be saved or used for other purposes.

One strategy to increase BAC testing at the time of arrest, and to eliminate the need for retrograde extrapolation, is the use of electronic warrants. In many jurisdictions law enforcement officers are able to contact on-call judges remotely at the time of arrest and have an electronic warrant sent directly to their smartphones or computers to avoid a delay in testing. Traditional means of obtaining warrants could take hours. These systems link the officer, prosecutor, and judges and allow for the generation, review, approval, and filing of warrants. Potential challenges related to electronic warrants include the availability of judges to be on call, which could be especially difficult in smaller jurisdictions; organizing the needed services for the blood draws, including during evenings and weekends; training for those who obtain the blood samples (including training to minimize risk to oneself or others); transport of a driver to a hospital or clinic if a trained phlebotomist is not available; and the issue of the chain of evidence for the blood sample, as the assessment of the sample would not be performed by the nurse/practitioner who draws the blood, but would need to be taken or sent to a laboratory for analysis. While hospital laboratories are generally open 24/7, this type of testing is not generally performed on an emergency basis for someone who is not a patient in the emergency department (ED) or hospital. The blood would likely be sent to a state laboratory for processing, thereby not providing an immediate answer to the question related to BAC. In addition, if there are any questions during

___________________

3Birchfield v. North Dakota, 136 S. Ct. 2160 (2016) consolidated with Bernard v. Minnesota, 844 N.W.2d 41 (Minn. Ct. App. 2014) and Beylund v. North Dakota, 859 N.W.2d 403 (N.D. 2015).

the case about the chain of evidence, the person who draws the blood may need to appear in court to attest to the fact that s/he drew the blood and handed it directly to the police officer who was then responsible for getting it to the next destination. However, many law enforcement agencies need to address these issues regardless of when the blood sample is taken from the defendant. Hedlund (2017) notes that many law enforcement agencies are currently considering transitioning to an electronic warrant system to improve efficiency. While electronic warrants are a promising strategy for obtaining accurate BAC results, more guidance is needed on how to implement them and the required infrastructure and protocols.

A passive test, such as using a flashlight that is equipped with an alcohol sensor, can help police officers screen drivers who they suspect have been drinking. These have been shown to increase the arrest rate for police officers who do not normally make DWI arrests (Fell et al., 2008), but the tests do not aid in charging or prosecuting a driver who may have been driving under the influence of alcohol. A recent survey of law enforcement agencies found infrequent use of passive tests, mainly due to a lack of equipment (Eichelberger and McCartt, 2016), although past research has also documented officer aversion to passive tests because of personal safety concerns (e.g., using the device brings the officer in close contact with the driver and occupies one hand) (Goodwin et al., 2015; Leaf and Preusser, 1996).

LEGAL SYSTEM INTERVENTIONS: ADJUDICATION

The adjudication process begins after an alcohol-impaired driver has been arrested. An offender could be arraigned the same day as the arrest or released to come back to court another time. Before pleading guilty at a court appearance, hearing, or trial, defendants may undergo an alcohol evaluation by a trained, certified individual in some jurisdictions or states; the driver is often referred to a treatment program if he or she meets the criteria for alcohol use disorder (AUD, DSM-5)4 (SAMHSA, 2005a). Whether or not screening is mandatory and when screening takes place vary by state (Chang et al., 2002), but the results can inform the prosecutor’s proposal to the judge, along with other additional information such as performance on the SFSTs, chemical tests, observations of the driver,

___________________

4 Alcohol use disorder, as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), is based on the presence of at least two symptoms from a specific set of criteria, with subclassifications of mild, moderate, and severe, whereas the DSM-IV defined two different disorders (alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence) with separate criteria for each. This has implications for how the categories compare across various research studies. In this chapter these disorders will be defined as the study authors defined them in their methodology.

statements made by the offender during the arrest process and/or testing, the offender’s driving history, and the effect on the victim if a crash was involved. If the driver is found guilty of alcohol-impaired driving, penalties could include fines, restitution, license suspension or revocation, ignition interlock installation, serving time in a correctional facility, or probation (Goodwin et al., 2015; SAMHSA, 2005a). A driver convicted of DWI could also be sentenced to complete a treatment program, participate in a monitoring program, or attend a victim impact panel (Goodwin et al., 2015; SAMHSA, 2005a). Many states have enacted various vehicle and license plate sanctions, including vehicle immobilization, impoundment, or forfeiture, and license plate impoundment and marked license plates for offenders with revoked or suspended licenses (Goodwin et al., 2015). Implementation of these laws varies by state and the evidence base for individual measures is mixed, but in general these sanctions reduce DWI recidivism (Goodwin et al., 2015; TRB, 2013a). States have varying sanctions for convicted DWI offenders, such as the number of DWIs that raise the charge to a felony, as well as more severe penalties for higher BAC levels or for having a child in the car at the time of arrest or crash (Goodwin et al., 2015).

There are some challenges that can impede the adjudication process for ensuring offenders receive proper sentencing and treatment. For example, because blood test results can take a long time to be processed, a prosecutor may have to proceed to trial without those results and therefore potentially rely on less information when presenting the case. Furthermore, information on past DWI convictions in other states may not be available to inform the decision of whether an offense should be increased to a felony charge (AAA, 2016; Robertson and Simpson, 2002). Additionally, there can be discrepancies between arrest and conviction data since some arrests may lead to a lesser plea, and therefore a driver’s conviction may not reflect the initial reason for arrest (see Chapter 6 for more details and information gaps regarding these data sources). For example, someone could be charged with reckless driving in addition to a felony DWI but that driver might plead guilty to the felony and have other charges dropped as a result of a deal with the prosecutor. Moreover, alcohol-impaired driving offenses could be reduced to non-alcohol-impaired driving offenses, or a defendant’s record could be sealed.

Prosecution Process

Limits on Diversion and Plea Agreements

After an alcohol-impaired driving arrest, some offenders are given the option of participating in a diversion program or taking a plea agreement.

A diversion program usually takes the form of education or treatment, and if the program is successfully completed, then the defendant may be given the option to plead to a non-alcohol-impaired driving offense such as reckless driving, for example, or in some cases, charges may be dropped and the infraction erased from the offender’s record (Goodwin et al., 2015). There is variation in the types of education and treatment used in diversion programs, and as a result, the evidence on whether they are effective is mixed (Voas and Fisher, 2001). A plea agreement is an agreement in which the defendant agrees to plead guilty in return for a concession from the prosecutor. Restrictions on when prosecutors can offer plea agreements have been found to reduce alcohol-impaired driving recidivism (Goodwin et al., 2015; Surla and Koons, 1989). Survey results indicate that up to 75 percent of alcohol-impaired driving cases are resolved with a plea agreement, and the concession offered is most often a reduced penalty (Goodwin et al., 2015; Robertson and Simpson, 2002). Concessions, however, vary by state, and in some states plea agreements result in the elimination of penalties and a clean record (Goodwin et al., 2015). Or, lesser offenses could remain on the record, and at least one state (Washington) maintains a record of completed diversion programs (McCartt et al., 2013).

When the record of an alcohol-impaired driving offense is erased or reduced through participation in a diversion program or a plea agreement, then it becomes impossible to identify recidivist offenders, reducing the severity with which their crime is perceived and in turn, the severity of the consequences associated thereof (Hedlund and McCartt, 2002; NTSB, 2000; Robertson and Simpson, 2002; TRB, 2005a). Grunwald et al. (2001) found that approximately 40 percent of alcohol-impaired driving offenders in Rhode Island that were charged as a first-time offender had previous alcohol-impaired driving arrests that had been erased from their records. As of 2014, 13 states had anti-plea-bargaining statutes limiting when a plea bargain can be offered (NHTSA, 2016). The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) rates limits on diversion and plea agreements as a four-star intervention (that is, demonstrated to be effective in certain situations) for reducing alcohol-impaired driving (Goodwin et al., 2015). The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB, 2000), the Transportation Research Board (TRB, 2005a), and the Traffic Injury Research Foundation (Robertson and Simpson, 2002) have also recommended limits on diversion and plea agreements.

Many DWI cases do not proceed to trial and offenders are instead offered participation in diversion programs or plea agreements with reduced charges (AAA, 2016; Robertson and Simpson, 2002; Voas and Fisher, 2001). This section reviews limits on diversion and plea agreements, but notes evidence on diversion program effectiveness is mixed

because program components and studies of them vary substantially. The only study directly examining plea agreement restrictions found reduced recidivism in three communities in response to the restrictions (Surla and Koons, 1989). Eliminated offenses because of a diversion program or lessened charges as a result of a plea agreement have implications for the severity of punishment and subsequent offender interactions with the criminal justice system, such as later DWIs, and therefore, general and specific deterrent effects (Robertson and Simpson, 2002). Based on older and mixed evidence on plea agreement restrictions and diversion programs, the committee concludes:

Conclusion 5-1: Research is needed on the effects of restrictions on diversion programs that remove alcohol-impaired driving convictions from a driver’s record and on the content of plea agreements for alcohol-impaired driving offenders as strategies to reduce DWI recidivism.

Administrative License Suspension/Administrative License Revocation Laws

Administrative license suspension (ALS) laws permit law enforcement officials to suspend an alcohol-impaired driver’s license at the time of arrest for refusing to submit or failing (i.e., the driver’s BAC is over the limit set by state law) a chemical test to determine his or her BAC. Administrative license revocation (ALR) laws require driver’s license reapplication after a suspension concludes. These pre-conviction laws apply to both first-time and repeat offenders. These measures are separate from criminal convictions; drivers convicted of DWI may also lose their licenses and face additional criminal sanctions. A temporary license, which can be valid from 7 to 90 days, allows time for an administrative hearing and for the driver to obtain alternative transportation (Goodwin et al., 2015; IIHS, 2017a).

ALS laws are enacted in 41 states and the District of Columbia,5 but they vary in the length of temporary license validity, length of suspension, and whether limited driving privileges can be restored during the suspension period (IIHS, 2017b). For example, Virginia’s suspension period is 7 days. Mississippi suspends offenders’ licenses for 90 days, and while Arizona’s suspension is the same length of time, offenders in that state are allowed limited driving privileges after 30 days. At least 12 states allow driving during the suspension period if the driver agrees to an ignition interlock device (IIHS, 2017b). A recent study found suspension periods of at least 91 days to be more effective than shorter periods (Fell and Scherer,

___________________

5 Nine states do not have ALS/ALR laws: Kentucky, Michigan, Montana, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, and Tennessee.

2017). NHTSA recommends an initial license suspension for at least 90 days for drivers with a BAC over 0.08% (or, 15 days followed by 75 days with a restricted license if the driver uses an ignition interlock device) and greater penalties for drivers who refuse a BAC test (NHTSA, 2006). Some states also allow a hardship provision, permitting the offender to drive to work or school (Goodwin et al., 2015). Although ALS laws have been challenged, court decisions have upheld these statutes, determining the laws ensure drivers’ due process as they provide a timely administrative hearing (IIHS, 2017c).

ALS and ALR laws are swift and certain; the consequences immediately follow the offending behavior, rather than following a conviction (Wagenaar and Maldonado-Molina, 2007). Many studies assessing the effectiveness of ALS and ALR laws were conducted as laws were enacted decades ago (Goodwin et al., 2015). These laws have been shown to affect alcohol-impaired driving crashes and fatalities (IIHS, 2017d; Talpins et al., 2014; Voas et al., 2000a). For example, one study found that alcohol-impaired driving crashes and first-time and repeat DWI convictions significantly declined after California’s ALS law was enacted (Rogers, 1997). Voas et al. (2000b) examined about 43,700 records of Ohio DWI offenders from 1990 to 1995. Compared to the time period before Ohio’s ALS law was enacted, the authors found reductions in DWI recidivism, moving violations, and crashes for first-time and multiple offenders after the law was implemented, although vehicle sanction legislation was also passed around the same time, which also could have affected driving outcomes. The recidivism rate within 24 months of arrest decreased from 15 to 5 percent for first-time offenders and from 25 to 7 percent among multiple offenders. Furthermore, crash involvement declined from 12 to 5 percent and from 14 to 7 percent among first-time and multiple offenders, respectively, in the 24 months after DWI arrest. Another large study that examined data in 38 states from 1976 to 2002 found a significant 5 percent reduction in alcohol-related fatal crash involvement and estimated the law(s) saved 800 lives per year (Wagenaar and Maldonado-Molina, 2007). This study found no significant effect of post-conviction suspension laws and concluded ALS policies are more effective in deterring alcohol-impaired driving than post-conviction license suspension or revocation (Wagenaar and Maldonado-Molina, 2007). While recent studies on cost-effectiveness of ALS and ALR laws have not been completed, a 1991 analysis of three states concluded that revenues generated from license reinstatement fees compensated for the laws’ operating expenses (Lacey et al., 1991).

License suspension or revocation does not, however, stop all DWI offenders from continuing to drive without a valid license (Goodwin et al., 2015; Lenton et al., 2010; McCartt et al., 2002), nor does it affect DWI

offenders’ alcohol consumption among those with AUD. Approximately half of first-time and repeat DWI offenders in one study delayed license reinstatement for at least 1 year (Voas et al., 2010a); those offenders who postpone license reinstatement are more likely to repeat the DWI offense compared to those drivers who reestablish their licenses (Voas et al., 2010b).

As described earlier in this chapter, the theory of deterrence relies on the perception of immediate, guaranteed, and severe punishment; well-implemented ALS and ALR laws ensure celerity and certainty of punishment (Goodwin et al., 2015; IIHS, 2017d). However, these laws are not in place in all states, and among those that have enacted laws, penalty severity varies among states. Although any suspension period is more effective than having no law, analyses favor ALS laws with longer suspension periods (Fell and Scherer, 2017). While there is a need for additional contemporary research, there is evidence from several studies that ALS and ALR laws have both general and specific deterrence effects, and the laws reduce alcohol-impaired driving crashes and convictions (Rogers, 1997; Voas et al., 2000a,b; Wagenaar and Maldonado-Molina, 2007). These effects can endure past the suspension period as well. In a recent study, Fell and Scherer (2017) found ALR laws had greater general deterrence effects than specific deterrence effects. This is an important finding because some offenders will continue to drive without a license, and these laws are one measure to deter alcohol-impaired driving among the general driving population. Other interventions, such as treatment, counseling, and ignition interlock devices (all discussed in more detail in this chapter), could complement ALS and ALR laws to prevent DWI recidivism (Goodwin et al., 2015; TRB, 2013a).

Conclusion 5-2: Nationwide adoption of effective administrative license suspension (ALS) and administrative license revocation (ALR) laws that provide for pre-conviction license suspension/revocation for refusing or failing a BAC test, that include an initial complete suspension, and that are based on updated model legislation would increase the effect of these laws.

Model legislation on ALS/ALR laws exists (NHTSA, 1986), but should be brought up-to-date. NHTSA could work with organizations that focus on state-level traffic laws and traffic safety to ensure that effective model laws (for example, full suspension for refusal to take a breath test) are in place and disseminated to states.

Treatment Related to the Adjudication Process

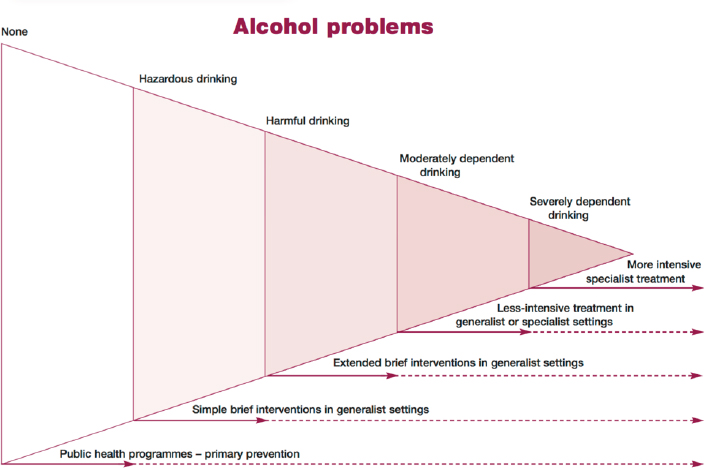

Different types of alcohol misuse necessitate the need for different, tailored types of interventions. Figure 5-1 shows a spectrum of problems related to alcohol misuse and the types of interventions that may be most beneficial for individuals suffering from each of these problems. The following sections describe some of these interventions and the individuals who may benefit the most from them, particularly among alcohol-impaired driving offenders. Although alcohol-impaired driving is a crime and law enforcement measures can be very effective, enforcement alone will not fully solve the problem of alcohol-impaired driving.

NOTES: Although the figure is not drawn to scale, the prevalence in the population of each of the categories of alcohol problem is approximated by the area of the triangle occupied; most people have no alcohol problems, a very large number show risky consumption but no current problems, many have risky consumption and less serious alcohol problems, some have moderate dependence and problems, and a few have severe dependence or complicated alcohol problems. In this figure, responses to alcohol problems include public health programs, brief interventions, and treatment. Each of these responses can differ with respect to the setting, duration, and intensity according to the problem.

SOURCE: Raistrick et al., 2006.

Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) and Convictions for Driving While Impaired

There is a spectrum of reasons individuals drive while alcohol impaired. For those who do not suffer from AUD (DSM-5), swift and appropriate sanctions and penalties, or the use of screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) are generally effective. However, apprehension for DWI is an opportunity to identify and provide resources to people with AUD across the entire spectrum. When a convicted individual has AUD, treatment is a key part of the adjudication process to help modify his or her behavior and reduce the likelihood of driving while alcohol impaired again.

More than 15 million adults and 623,000 adolescents had AUD in 2015, according to results from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (SAMHSA, 2016a). Furthermore, AUD is a highly comorbid condition; 2.7 million adults with AUD in 2015 also had an illicit drug use disorder (SAMHSA, 2016b). Data from the 2012–2013 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III showed both 12-month and lifetime AUD were significantly associated with other drug disorders, mood disorders including major depressive and bipolar I disorders, and antisocial and borderline personality disorders (Grant et al., 2015). There is no evidence whether interventions geared toward the general public (e.g., alternative transportation) will be as effective for DWI offenders with AUD. Furthermore, those who drink and drive may also drive while impaired by drugs (Talpins and Rogers, 2017; Talpins et al., 2015). For example, a study of 92 drivers arrested for DWI in Florida found that 41 percent tested positive for at least one of seven drug categories; the most prevalent drugs included cannabinoids, benzodiazepines, and cocaine (Logan et al., 2014).

Among those convicted of DWI, rates of alcoholism appear to increase as the number of DWI convictions increases (Cavaiola et al., 2003). A cohort study found that people with multiple DWIs are five times more likely than the general population to have an alcohol abuse or dependence diagnosis (DSM-IV) (Lapham et al., 2011). Brinkmann et al. (2002) found that more than 80 percent of individuals who drove with a BAC higher than 0.19% were alcoholics in a sample of alcohol-impaired drivers.6

Recent national estimates on how many DWI offenders are diagnosed with AUD in the general population are not available in the published literature. Hingson7 of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alco-

___________________

6 “Alcoholic” is defined in this study by Alc-Indices (calculated using methanol, acetone, 2-propanol, γ-GT, and CDT concentrations).

7 Personal communication with Ralph Hingson, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism on April 13, 2017. Available by request from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s Public Access Records Office (PARO@nas.edu).

holism (NIAAA) performed a descriptive analysis on data from the 2012 and 2013 National Epidemiology Survey and Related Conditions and found that among the 8 percent (n = 2,091) who reported driving after drinking in the past year, 25 percent met criteria for mild AUD, 21 percent moderate AUD, and 30 percent severe AUD. In the total population, 9 percent met criteria for mild AUD, 5 percent for moderate AUD, and 5 percent for severe AUD.8Stasiewicz et al. (2007) found 4.2 and 4.4 percent of convicted DWI offenders from a sample in Erie County, New York, were diagnosed with alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence, respectively (DSM-IV).

Screening DWI offenders for alcohol abuse problems is mandatory in most states, but not all; results can be used to inform treatment recommendations to the court (Chang et al., 2002). Sometimes formal screening methods involving testing and interviewing are used (Chang et al., 2001), but most courts use self-reported information from DWI offenders to screen for AUD, usually by having them complete a simple questionnaire about their alcohol use (NIAAA, 2004/2005). Offenders, however, often underreport their alcohol use for fear of punishment, judgment, or breach in confidentiality, resulting in a missed treatment opportunity for many (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 1995; Knight et al., 2002; Lapham et al., 2002, 2004). Although there are effective AUD screening guidelines available (Chang et al., 2002), courts generally cannot hire people specifically trained to screen for AUD because of financial limitations (Knight et al., 2002). The amount it would cost courts to screen and treat these individuals, however, is often much less than the cost of incarceration (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 1995; NIAAA, 2004/2005).

Court assessment, referral, intervention, and treatment strategies for DWI offenders vary substantially across the United States (Cavaiola and Wuth, 2014). Some forms of treatment for DWI offenders include motivational interviewing, brief interventions, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and counseling (Robertson et al., 2008; SAMHSA, 2005a). Sentencing practices for driving under the influence of alcohol also vary by state. For example, courts in Washington provide a DWI sentencing grid based on BAC result and number of prior offenses to help judges determine appropriate punishments for DWI offenders. As noted, expanded alcohol assessment and treatment is deemed mandatory in the sentencing grid for any offender with two or three prior offenses (Washington Courts, 2016). A similar sentencing grid created by NHTSA in 2005 recommends alcohol use assessment and treatment for all repeat offenders (NHTSA, 2005).

___________________

8 Ibid.

Not all public court sentencing records are available electronically. In most states, court records are available on their website and are searchable by last name or court date, but only by county; they are often unreliable because all data are not routinely entered (see Chapter 6 for more information on data collection). For specific information, such as whether the offender was screened for AUD, one must often contact the court where an individual’s action was filed. The number of DWI arrests made per year by state is available through the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) program (FBI, 2010), but these data are neither comprehensive nor timely (Rosenfeld, 2007). The UCR program is made up of crime data reports submitted by police agencies across the country, but these crime rates are often underestimates because of barriers to monitoring and reporting such as financial restrictions, staffing changes, inadequate training, natural disasters, and new computers or crime reporting systems (Maltz and Targonski, 2002). Some states, like California, have been able to overcome these barriers and track not only arrest rates but also types of DWI convictions (Daoud et al., 2015).

DWI Courts

DWI courts are specialized courts aimed at changing DWI offenders’ behavior through comprehensive monitoring and substance abuse treatment. As a part of the DWI control system, these post-conviction courts are a systematic mechanism for holding offenders accountable for their actions while treating the underlying cause(s) of their impaired driving. They are a voluntary alternative to traditional probation (Fourth Judicial District Minnesota Judicial Branch, n.d.; Hawaii State Judiciary, n.d.). DWI courts are modeled after the successful drug court system (NADCP, n.d.) and are founded on 10 guiding principles (see Box 5-1).

Some DWI courts are a subset of drug courts; as of August 2014, there were 216 DWI courts across 31 states and 409 hybrid DWI/drug courts (Goodwin et al., 2015). In a 2016 survey, 40 percent of DWI courts reported primarily serving urban areas; more than one-third of programs indicated they mainly serve rural areas, but no respondents described principally serving tribal territory (Block, 2016). DWI courts reported predominantly white, fully employed participants (Block, 2016).

DWI courts are team-based, in which the judge, prosecuting and defense attorneys, probation officer, and treatment staff familiar with DWI laws and addiction issues work together to ensure an effective and individualized sentencing and treatment plan for the offender (Goodwin et al., 2015). Teams meet frequently to report program infractions, offer positive reinforcement, and modify restrictions when deemed appropriate. DWI courts’ intensive supervision involves observing the offender in public,

at home, and at work. This includes adherence to a treatment plan, use of ignition interlocks or car impounds, and alcohol and drug testing (using transdermal or breath test devices). Offender clinical assessments involve screening for alcohol triggers and drug abuse, evaluating physical and mental health, and considering employment and financial status. Motivation for change also plays a role in the treatment plan, which is usually multicomponent and incorporates effective medications (for a discussion of medications, see section on pharmacological treatments), behavioral therapies, peer support groups, and social skills training (NCDC, n.d.-a). Court programs typically last 1 to 3 years, and supervision can be lessened as participants move through a program’s different phases (Block, 2016; Goodwin et al., 2015; Hawaii State Judiciary, n.d.; NCDC, n.d.-b). Courts vary in requirements for serving jail time before entering the program; sentences usually do not change after program completion, although some programs reduce sentences (Block, 2016). Participants may be removed from programs for noncompliance or new charges (Block, 2016; Circuit Court of the State of Oregon, n.d.).

Evidence suggests that traditional court processes and sanctions are generally not effective in influencing the behavior of offenders with multiple DWIs (Goodwin et al., 2015; NCDC, n.d.-c). One-third of those arrested annually for driving impaired have a prior DWI conviction (NCDC, n.d.-b). Therefore, most DWI courts are aimed at offenders who have at least one prior DWI and/or who drove with a BAC of 0.15% or higher (NCDC, n.d.-c). DWI courts may disqualify offenders also convicted of felonies or violent crimes (Block, 2016; Hawaii State Judiciary, n.d.; NCDC, n.d.-a). Furthermore, 65 to 80 percent of first-time DWI offenders will not reoffend, and contact with the criminal justice system may offer enough deterrence for first-time offenders to avoid future impaired driving (Goodwin et al., 2015; NCDC, n.d.-b). DWI court resources are best directed toward repeat offenders with whom the treatment program can have the biggest effect. Only about 1 percent of those arrested for DWIs, however, are referred to a specialty court, and approximately half of those referred complete the program (Sloan et al., 2016).

A 2009 systematic review concluded DWI courts are an effective intervention in reducing recidivism, but found many studies were methodologically weak and encouraged additional future research (Marlowe et al., 2009). For example, one of the stronger studies in the review determined participants in an Oregon DWI court were less likely to be convicted of a DWI or other traffic violations (Lapham et al., 2006). Furthermore, 85 percent of studies in a 2012 meta-analysis favored DWI courts over traditional courts (Mitchell et al., 2012). Three of the four randomized studies reviewed in the meta-analysis found DWI courts reduced the odds of recidivism (Mitchell et al., 2012). The fourth experimental study, an

evaluation of a DWI court in Los Angeles County, did not find significant differences in drinking behavior or recidivism between the participants assigned to the DWI court and those assigned to a control group (traditional criminal court) during a 24-month follow-up period (MacDonald et al., 2007). The authors note limited jail time in the county for DWI offenders during the study period likely affected incentive to participate in the voluntary DWI court (MacDonald et al., 2007). However, this DWI court was created as an investigational program for a research study, and as such, was not pilot-tested or evaluated for compliance with DWI court guiding principles (Marlowe et al., 2009). Furthermore, aspects of the traditional court (control group) could be considered important elements of a DWI court (such as the number of status hearings in the first 6 months), so the two groups of participants received similar interventions (Marlowe et al., 2009).

Mitchell et al. (2012) found that more DWI court participants graduated from DWI programs compared to adult and juvenile drug court participants (Mitchell et al., 2012). DWI courts characterized by longer program duration and higher quantity of services usually have a higher completion rate, and graduates experience better outcomes, including increased educational fulfilment and enhanced employment status (Robertson et al., 2016; Sloan et al., 2013).

DWI courts have long-term effects on offenders as well. A study of DWI courts in North Carolina found reduced rates of recidivism over 4 years compared to people not referred to the specialty court (Sloan et al., 2016). Similar long-term, positive results were observed in an analysis of three Georgian DWI courts; recidivism rates of comparison groups matched by the number of previous DWI convictions, sex, and age were between 24 and 35 percent, while DWI court graduates’ recidivism rate was 9 percent (Fell et al., 2011; Goodwin et al., 2015; NCDC, 2015). Additionally, DWI courts may be more effective than hybrid DWI/drug courts in preventing DWI recidivism because drug courts enroll several types of participants and do not specifically target DWI offenders (Sloan et al., 2016).

Many DWI courts are funded through federal, state, and county grants as well as fees collected from offenders (Block, 2016). Participants often have to pay for program components such as alcohol monitoring and ignition interlocks, substance abuse treatment, and any imposed fines (Carey et al., 2008; Circuit Court of the State of Oregon, n.d.; Fourth Judicial District Minnesota Judicial Branch, n.d.). Although more resources (e.g., time and staff) are needed to provide DWI courts’ close monitoring, these courts do not cost more, and sometimes cost less, in up-front costs than traditional probation (Goodwin et al., 2015; NCDC, 2015). Additionally,

courts save money by reducing rearrests and total time offenders spend in jail (Carey et al., 2008; NCDC, 2015; NPC Research, 2014).

DWI courts are voluntary programs that couple offender supervision with individualized treatment; courts target high-need offenders who can benefit the most from these components. Characteristics of DWI court programs matter; analyses favor longer program duration and higher intensity contact between the participant and the DWI court (Sloan et al., 2013). Well-done studies by Fell et al. (2011), Lapham et al. (2006), and Sloan et al. (2016) demonstrate that DWI courts have short- and long-term specific deterrent effects. A meta-analysis (Mitchell et al., 2012) generally supports these individual findings, though some methodically weak studies of DWI courts (e.g., inadequately controlling for selection bias) and varying study designs result in different findings. The field could benefit from additional well-designed and executed studies that adhere to established standards. To improve health and safety outcomes and reduce recidivism of repeat offenders and high BAC offenders, the committee recommends:

Recommendation 5-1: Every state should implement DWI courts, guided by the evidence-based standards set by the National Center for DWI Courts, and all DWI courts should include available consultation or referral for evaluation by an addiction-trained clinician.

Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT)

SBIRT may serve to identify hazardous and harmful alcohol intake, as well as provide an opportunity for immediate intervention and referral to treatment, if necessary. DWI offenders are an important population to screen and treat for AUD (DSM-5). As noted earlier, there is not a reliable estimate of AUD among DWI offenders in the criminal justice system (Lapham et al., 2004). However, research suggests recidivists generally exhibit heavier and more frequent drinking behavior (Mullen et al., 2015). Additionally, only about a quarter of impaired drivers treated in EDs are convicted, so many of these offenders do not receive treatment through a court referral (Higgins-Biddle and Dilonardo, 2013). Importantly, many alcohol-impaired driving episodes are caused by binge drinkers, rather than heavy drinkers, so it is equally important to identify these patients and provide treatment before they are involved in an alcohol-impaired driving crash (Flowers et al., 2008; Higgins-Biddle and Dilonardo, 2013). It is clear then that SBIRT plays a role in the other phases of the committee’s framework (see Figure 1-5), but it is included in this chapter as it is

relevant to many of the treatment options that follow screening and brief intervention.

The main goal of SBIRT is to increase a patient’s awareness and understanding of the risks of excessive drinking and to motivate him or her to decrease his or her consumption (Agerwala and McCance-Katz, 2012). A range of health care workers can conduct SBIRT in a variety of settings, including the criminal justice system, EDs, primary care, behavioral health care, and college campuses. Screening, the first component of SBIRT, is usually done using one of several tools (e.g., AUDIT or CAGE) that have been tested and demonstrated to be effective in documenting alcohol consumption as well identifying at-risk alcohol consumption or possible AUD. This may be done in one of several ways: orally, in writing, via computer, or other electronic means (Agerwala and McCance-Katz, 2012; Higgins-Biddle and Dilonardo, 2013). If the screening results indicate at-risk alcohol consumption such as binge drinking or exceeding the recommended limits for low-risk consumption, a brief intervention is performed. In cases in which possible AUD is identified, a more thorough assessment may be done, and the brief intervention may focus on motivating the patient to begin treatment.

A brief intervention is a short, tailored, one-on-one counseling session, usually lasting between 5 and 30 minutes, that uses techniques from motivational interviewing, brief negotiated interviewing, and/or CBT to try to eliminate harmful drinking behaviors such as binge drinking and alcohol-impaired driving (NIAAA, 2005a; SAMHSA, n.d.). During the intervention, practitioners deliver the results of the screening, provide information on low-risk alcohol consumption, assess the patient’s motivation to change his or her alcohol consumption, and collaboratively set goals for decreasing consumption (Higgins-Biddle and Dilonardo, 2013). Brief interventions can vary considerably and may consist of one to four sessions depending on the severity of the patient’s alcohol problem, the setting, the clinician’s expertise, and time constraints (NIAAA, 2005a). Once the brief intervention is completed, the patient may receive follow-up in a primary care or behavioral health setting, or be referred for more extensive treatment if needed (NIAAA, 2005a). Treatment plans can vary in scope and duration, and they are tailored to the patient’s specific needs.

Several studies present strong evidence that brief interventions can effectively decrease harmful alcohol consumption (Dunn et al., 2001; Moyer et al., 2002; Vasilaki et al., 2006), especially when conducted in emergency care settings (D’Onofrio and Degutis, 2002; Nilsen et al., 2008), primary care settings (Ballesteros et al., 2004; Bertholet et al., 2005; Kaner et al., 2009; O’Donnell et al., 2014), and college settings (Carey et al., 2007; Larimer and Cronce, 2002). The evidence is inconclusive on whether brief alcohol interventions are effective in general hospital settings (Emmen et

al., 2004), among repeat DWI offenders (Brown et al., 2010; Miller et al., 2015; Ouimet et al., 2013), among heavy drinkers or those with alcohol dependence (Saitz, 2010), or among adolescent drivers (Steinka-Fry et al., 2015; Yuma-Guerrero et al., 2012); therefore, more research is needed in these areas. Current studies rely on self-reports of alcohol consumption and include participants who partake in SBIRT and then return for a follow-up assessment. To counteract self-reporting and self-selection bias, future research would benefit from analyzing population health effects in real-world settings. There is also evidence to suggest the positive effects of SBIRT wane over time, and further research is needed to determine the optimum frequency of interventions (O’Donnell et al., 2014). More investigation is also needed into whether brief interventions reduce alcohol-impaired driving (Dill et al., 2004), although at least one study has shown a brief intervention to be effective in decreasing drinking and driving (D’Onofrio et al., 2012).

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends all adults receive SBIRT at primary care visits (USPSTF, 2013). A recent study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, however, found that only one in three self-reported binge drinkers were screened for alcohol misuse at their last checkup and told that their drinking was risky, and only one in six were screened and advised to reduce their drinking (McKnight-Eily et al., 2017). Primary care physicians have an opportunity to increase their use of SBIRT, allowing them to reach more patients engaging in risky drinking and reduce alcohol-impaired driving injuries. There are barriers, however, that make universal screening difficult. Beich et al. (2003) found approximately 9 percent of patients will screen positive for risky drinking behavior in primary care settings. Madras et al. (2009) found that when EDs and clinics are included, approximately 23 percent of patients screened will self-report risky drinking behavior. These low percentages cause some physicians, who are already strapped for time and resources, to discount SBIRT as an efficient use of their time (Beich et al., 2003). Staff training is also necessary before SBIRT can be effectively administered, which takes additional time and resources (Bernstein et al., 2009; Nilsen et al., 2006).

In addition to busy workloads and financial constraints, other barriers to administering SBIRT include

- underreporting of drinking by patients;

- health care professionals not seeing SBIRT as part of their job;

- more immediate, competing health problems (especially in the ED);

- lack of physician knowledge about alcohol guidelines;

- cultural differences in alcohol consumption; and

- that the topic of alcohol abuse can be a difficult one to discuss (Johnson et al., 2011).

Yokell et al. (2014) found that brief interventions were administered more often in rural EDs and less often in crowded, metropolitan EDs owing to time and financial constraints. In contrast, Colorado initiated a statewide SBIRT initiative over 10 years ago and has documented the strategies necessary for successful implementation of an SBIRT program, including clinical issues, training for health professionals, and reimbursement (Nunes et al., 2017). The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) funded a national initiative to implement SBIRT in general medicine and community settings. Evaluation of 11 of the programs demonstrated that the method used by SAMHSA was an effective way to implement the programs (Bray et al., 2017).

There are also legal reasons why a physician may be hesitant to screen a patient for alcohol misuse. Physicians are required to report “at-risk drivers” to their state Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) in six states: California, Delaware, Nevada, New Jersey, Oregon, and Pennsylvania (AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety, 2016; State of Nevada, n.d.). The guidelines on which conditions physicians must report, however, are vague and vary by state. All states allow physicians to report medically at-risk patients to the DMV in good faith. Many physicians are more comfortable reporting an impaired driver to the DMV’s medical review board rather than to the police (Mello et al., 2003). The reported information is confidential in all states, but most states will release it if they receive a court order (AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety, 2016). Hesitant physicians may be concerned about patient confidentiality and the risk of civil action against the physician (Mello et al., 2003). Furthermore, the implementation of a law in Ontario, Canada, requiring physicians to warn medically at-risk drivers of the consequences of alcohol-impaired driving resulted in a reduced rate of crashes requiring emergency care, but the warning was also associated with increased depression and fewer subsequent doctor visits, suggesting that physicians should decide which patients would benefit most from a warning (Redelmeier et al., 2012). However, warning drivers of consequences without performing interventions to address risky drinking may be part of the difficulty with this approach.

Finally, insurance reimbursement policy may dissuade practitioners from administering SBIRT, although commercial insurance, Medicare, and Medicaid provide reimbursement for SBIRT (SAMHSA, 2017). The Uniform Accident and Sickness Policy Provision Law (UPPL) authorizes health insurance companies to deny claims for injuries sustained while intoxicated, including those that result from driving under the influence (Chezem, 2005). As of 2016, UPPL remains in place in 24 states (APIS,

2016). The National Conference of State Legislators worked to repeal UPPL laws and to ensure that states did not introduce new restrictions on insurance payments. O’Keeffe et al. (2009) assessed the costs associated with caring for patients who are intoxicated compared to those who are not and discussed the implications for costs borne by trauma centers in states with UPPL. The findings showed that alcohol consumption by minimally injured trauma patients is correlated with higher hospital charges, which are exacerbated in UPPL states, and, the authors conclude, are likely to increase with implementation of SBIRT. Gentilello et al. (2005a) analyzed survey data from trauma surgeons and identified UPPL as an important barrier to alcohol screening. The results indicated strong support for alcohol screening and intervention programs, yet the majority (51 percent) of surgeons reported not routinely measuring BAC. Furthermore, almost one-quarter of surgeons reported having a payment denied in the past 6 months based on alcohol screening results. Interestingly, SBIRT does not identify whether the visit at which SBIRT is being performed is for treatment of an alcohol-impaired driving injury, as the screening tool documents patterns of alcohol use, rather than report of use for a single incident. Because of this, SBIRT in itself may not contribute to denial of coverage for an injury.

It is important to note that SBIRT may be performed by a number of members of the health care team who have been trained in its use, which is one way to overcome the limitations of physician time and financial resources (Johnson et al., 2011). This includes nurses, social workers, health educators, and others who interact with patients on a regular basis. Education and training programs have been developed and disseminated through several initiatives by federal agencies, professional organizations such as the American College of Emergency Physicians and the Association for Medical Education and Research in Substance Abuse, and academic centers (ACEP, n.d.; AMERSA, n.d.). Studies have demonstrated that health promotion advocates, who do not have a professional license, can effectively perform SBIRT in the ED (Bernstein et al., 2009; D’Onofrio and Degutis, 2010). Carnegie et al. (1996) found that when provided with proper training, receptionists were open to helping with preventive medicine tasks. Several studies also suggest that SBIRT is cost-effective in the long term because it reduces health care costs by addressing risky alcohol behaviors before they lead to injury (Estee et al., 2010; Fleming et al., 2002; Gentilello et al., 2005b). A redistribution of ED resources that prioritizes SBIRT training and implementation may therefore make financial sense.

As discussed in this section, the evidence on SBIRT’s efficacy is strong, but it requires resources, training, and time. Many of the barriers outlined above could also be overcome through new technology that electronically administers screening and brief interventions to patients, such as at

computer kiosks, on tablets, or through smartphone applications and text messages. The Community Preventive Services Task Force9 recommends electronic screening and brief interventions to curtail harmful alcohol consumption (Community Preventive Services Task Force, 2012), and evidence suggests that electronic screening and brief interventions delivered through interactive, online programs and smartphones are effective (Donoghue et al., 2014; White et al., 2010).

Mobile health approaches have emerged as a promising strategy for expanding behavioral alcohol interventions (Kazemi et al., 2017; Muench et al., 2017). Recent studies by Suffoletto et al. (2014, 2015) found that brief interventions delivered by text messages were successful in reducing self-reported binge drinking among young adults discharged from the ED. In fact, findings from Suffoletto et al. (2015) suggested that an intervention consisting of an interactive text message with tailored feedback was more effective than self-monitoring without feedback and no text messaging or feedback (the control condition) in reducing alcohol consumption and related injury. These findings were consistent with a previous study, which also used text messaging to provide feedback to young adults who were identified as hazardous drinkers. The study findings showed that the text message intervention reduced heavy drinking; young adults who received the intervention reported about two fewer drinks per drinking day than they did at baseline and approximately three fewer heavy drinking days in the last month (Suffoletto et al., 2012).

A randomized controlled pilot study tested four types of alcohol-reduction themed text messages for problem drinkers. Participants significantly reduced their weekly drinking in response to loss-framed (i.e., conveys the consequences of harmful drinking) and tailored (i.e., conveys messages tailored to the individual’s baseline assessment and goal achievement) messages (Muench et al., 2017). There are many opportunities to reach more patients with alcohol problems as technology continues to develop, but further research is needed to identify which elements of electronic interventions are key to initiating behavioral changes (Bewick et al., 2008). The following sections discuss various treatment and program strategies for people who have AUD or engage in harmful drinking behaviors such as binge drinking.

___________________

9 The Community Preventive Services Task Force was formerly known as the Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Task Force publications prior to 2012 are cited as the latter, and those published after 2012 are cited as the former.

Use of Medications for Alcohol Use Disorders

There are four medications approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of alcohol dependence: naltrexone (NTX), extended release naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram (NIAAA, 2005b). NTX is an opioid receptor antagonist approved for the treatment of opioid addiction and AUD (SAMHSA, 2016c). It is taken as a 50 mg pill once per day and has been shown to reduce alcohol consumption and cravings in those with alcohol dependence (Lobmaier et al., 2011; SAMHSA, 2016c). NTX is effective because it blocks the feelings of euphoria associated with alcohol intoxication and has no abuse potential (O’Brien et al., 1996; Roozen et al., 2006). Oral NTX, however, is known for having poor adherence rates (Swift et al., 2011), possibly because of its initial side effects of nausea, vomiting, dizziness, and fatigue, or the patient belief that it is not effective (Carmen et al., 2004; Rohsenow et al., 2000; Srisurapanont and Jarusuraisin, 2005). Research also indicates that family history of alcohol dependence and genetic variations can influence the efficacy of NTX. Most notably, a polymorphism of the µ-opioid receptor gene may be positively associated with the efficacy of NTX (Chamorro et al., 2012; Garbutt et al., 2014; Oslin et al., 2006). Further research is needed to confirm these moderating effects. They have the potential to influence physician decision making by identifying subgroups that are more likely to respond positively to NTX.

Extended-release naltrexone requires intramuscular injection into the gluteus muscle at 380 mg per month (SAMHSA, 2016c). This schedule greatly improves adherence to treatment. The medication has the potential to increase compliance as it requires less frequent administration than NTX. Over 5 percent of users, however, experience complications at the injection site including induration, swelling, nodules, and itching (Walker et al., 2017). Injection site reactions can occur if the injection is made into fat rather than muscle. A recent study by Walker et al. (2017) suggests that a modified injection technique in which the needle is inserted at a 40 degree angle may help decrease injection site complications. Long-acting depot formulations or implants of NTX have also been under development and show promise in terms of increasing treatment efficacy and decreasing noncompliance rates (Goonoo et al., 2014). Although they are not yet approved by FDA, these new delivery systems have the potential to release NTX to the brain for up to 7 months after insertion (Goonoo et al., 2014). More research on the safety and tolerability of these medications is needed before they can be released for use by the general public (Goonoo et al., 2014). All FDA-approved addiction medications are covered by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, and the high cost of naltrexone and extended-release naltrexone to prevent relapse is considered justified by the high cost of alcohol relapse.

Two pilot studies analyzed the specific effects of NTX on alcohol-impaired driving. The first study examined the efficacy of NTX on treating repeat DWI offenders. The researchers found that with NTX, participants’ daily drinks decreased by 77 percent and that vehicular failures to start because of an ignition interlock activation decreased from 3.1 to 1.29 percent of tests (Lapham and McMillan, 2011). The second study analyzed the feasibility and effectiveness of using extended-release NTX to treat alcohol dependence (DSM-IV) in three drug court settings. The researchers found that NTX treatment was associated with 57 percent fewer missed court sessions and a reduction in positive drug and alcohol tests (Finigan et al., 2011). An endpoint analysis found that 26 percent of standard-care clients were rearrested compared to 8 percent of clients treated with NTX (Finigan et al., 2011). Randomized, clinically-controlled trials that look specifically at NTX effects on alcohol-impaired driving are needed.

Acamprosate is a glutamate antagonist that is administered in two 333 mg tablets three times per day and is used to maintain abstinence of alcohol after withdrawal has occurred (SAMHSA, 2005b). A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of medications for treating AUD (DSM-5) found that oral NTX and acamprosate are equally effective in reducing rates of drinking relapse (Jonas et al., 2014). NTX has been shown to be more effective in reducing heavy drinking and craving, while acamprosate has been shown to be more effective in maintaining abstinence (Carmen et al., 2004; Maisel et al., 2013; Mann, 2004; Rösner et al., 2008). Research suggests that the combination of NTX and acamprosate is safe and more effective than treatment with either medication alone (Feeney et al., 2006; Kiefer and Wiedemann, 2004). The most common side effect from acamprosate is diarrhea, but this has not been shown to cause any problems in medication adherence (Carmen et al., 2004).

Disulfiram, the first medication approved by the FDA to treat alcohol dependence, is an alcohol-sensitizing agent that causes physical reactions such as sweating, hyperventilation, head and neck throbbing, nausea, vomiting, and weakness when the patient consumes any alcohol (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 2009). Once alcohol has been ingested it usually takes 10 to 30 minutes for this reaction to occur; the intensity shows individual variation (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 2009). Disulfiram is taken as a pill of 125 to 500 mg once per day (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 2009). Evidence on the effectiveness of disulfiram in treating alcohol dependence is mixed. There is compelling evidence to indicate that disulfiram decreases alcohol consumption when the drug is taken in a controlled laboratory setting (Fuller et al., 1986). In real-life settings, however, adherence is very difficult to maintain and ingestion of the medication must be supervised in order to be effective

(Brewer et al., 2000). In addition to compliance issues, high doses of alcohol and disulfiram can be life threatening, leading some physicians to dismiss it as a viable treatment option (Williams, 2005). Disulfiram is most effective and safe when used in substance abuse treatment programs where patients can be closely monitored (Schuckit, 2006).

Topiramate is an antiepileptic drug that was approved by FDA to prevent seizures. It can be used off-label to treat alcohol dependence as well (Kenna et al., 2009). It has been reported to decrease cravings and promote alcohol abstinence by mimicking the presence of alcohol in the brain (Ait-Daoud et al., 2006). Topiramate is taken as a 15 to 200 mg pill twice per day (Kenna et al., 2009). A meta-analysis of pharmacotherapy concluded there is moderate10 evidence to suggest that topiramate is associated with fewer drink days, fewer heavy drinking days, and fewer drinks per drinking day (Jonas et al., 2014). One review found oral naltrexone and topiramate were equally effective in increasing days of abstinence in those with alcohol dependence (DSM-IV), while acamprosate was only moderately effective (Miller et al., 2011). Topiramate has some side effects that may affect adherence including paresthesia, taste perversion, anorexia, and difficulty concentrating (Johnson et al., 2007). A study conducted on patients taking topiramate for long-term prevention of seizures found that cognitive slowing and dysphasia were the main reasons the medication was discontinued (Bootsma et al., 2004). Topiramate holds promise in producing self-efficacy to resist heavy drinking among a subset of heavy drinkers identified by a specific genotype (Kranzler et al., 2016),11 but further research is needed to understand how the drug affects alcohol-impaired driving.

Evidence suggests that most antipsychotics are not effective in reducing drinking or craving in patients with alcohol dependence (DSM-IV) (Kishi et al., 2013). While the antipsychotic quetiapine has shown some promising effects in treating alcohol dependence and abuse (DSM-IV) because of its effects on mood, anxiety, and sleep, more research is needed to determine its usefulness and to identify patients most likely to benefit from it (Ray et al., 2010).

Although psychopharmacological approaches to treating AUD have been shown to be cost-effective (Burton et al., 2016; Zarkin et al., 2010) and effective in reducing heavy drinking, medications are underused. In 2016, a survey of DWI courts reported that 31 courts used NTX for alcohol

___________________

10Jonas et al. (2014) based the strength of evidence on published guidance on comparing medical interventions from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Owens et al., 2008).

11 Heavy drinking was defined in this study as average weekly consumption of 18 and 24 standard drinks for women and men, respectively (Kranzler et al., 2016).

treatment services and 3 courts used acamprosate (Block, 2016). A 2008 study analyzed state-level policies and their association with the use of NTX in treatment facilities. They found that Medicaid policies that support the use of generic drugs were associated with higher NTX use while policies with preferred drug lists and restricted pharmacy network were not (Heinrich and Hill, 2008).

The quality of the evidence for the efficacy of anti-relapse medications is excellent. For NTX, the first such medication approved by FDA for efficacy in preventing relapse, the evidence is based on placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trials conducted in multiple countries throughout the world. The most reliable finding for success is not total abstinence from drinking, but rather a reduction in the number of heavy drinking days. This translates into fewer opportunities to drive a vehicle in an alcohol-impaired state. While there are reports from drug courts on the benefits of using medication as a means of preventing relapse to alcohol-impaired driving, the published controlled trials were not conducted among drug court participants. The evidence for NTX, acamprosate, and topiramate is mainly based on controlled trials and meta-analyses, while that for disulfiram is poor for efficacy because of high drop-out from treatment. NTX, extended-release NTX, acamprosate, disulfiram, and topiramate all appear to be effective in certain situations, but more research is needed to determine which medications are most beneficial for which patients. Most of the research on the effects of these medications has been done on adults; future research should analyze the effectiveness of pharmacotherapy for younger populations of driving age (Stockings et al., 2016). Although medication is a helpful tool in treating people with AUD, research indicates that psychosocial therapy given in conjunction is beneficial (Miller et al., 2011; Rohsenow, 2004; Roozen et al., 2006; Srisurapanont and Jarusuraisin, 2005).

Conclusion 5-3: Though effect sizes vary, medications in combination with other treatment modalities to treat individuals with alcohol use disorder who have been convicted of alcohol-impaired driving can reduce impaired-driving recidivism.

While a single DWI does not imply an illness, repeat offenders have a high probability of having an AUD. This, like other addictions, is a disease of the brain and requires long-term treatment to prevent relapse. The offender needs to be evaluated by a clinician with addiction training and, if medically indicated, placed in a program that includes relapse prevention medication and the requirement for an extended period of attendance in therapy (see the following section for a discussion of one such therapy—CBT). Because there are barriers to adherence to medication,

success in some DWI programs for repeat offenders has involved monthly injections of extended-release naltrexone. As explained above, this medication reduces reward from alcohol drinking, has minimal side effects, and often reduces craving for alcohol. The result reported in most studies is a reduction in heavy drinking, though not total abstinence. There are many barriers to AUD treatment, including stigma, comorbid conditions requiring treatment, lack of perceived need for treatment or motivation for change, lack of adequate training among health care professionals, and decreased access to or increased cost of medications or providers (Knudsen et al., 2011; NIAAA, 2010; Schuler et al., 2015). Furthermore, offenders could refuse to comply with compulsory treatment components of sentences, after which they would face additional punishment; motivational enhancement therapy could be helpful for these offenders (Dill and Wells-Parker, 2006).

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

CBT is a structured behavioral therapy that helps patients solve problems by changing their patterns of thought and therefore their behavior and coping strategies in response to daily situations. There are several effective approaches to CBT in addressing AUD. For example, motivational interventions are relatively brief and focus on readiness to change behavior (Magill and Ray, 2009; Miller and Rollnick, 2002). Contingency management involves the provision of some type of material reinforcement when an individual refrains from drinking alcohol (Petry et al., 2000; Prendergast et al., 2006). The community reinforcement approach is focused on making sobriety more rewarding than alcohol use. Behavioral couples therapy centers around the effects of alcohol use on the relationship (Epstein and McCrady, 1998; Powers et al., 2008). CBT can also be made available online or through other communication technologies, making it more accessible to patients in remote areas. For example, CBT has been adapted to interactive voice response for continuing care after AUD treatment (Rose et al., 2015) and other mobile or Internet-based tools for a variety of conditions (Blankers et al., 2011; Marsch et al., 2014; Vallury et al., 2015).

CBT may also be used in conjunction with other therapies, such as medications that have demonstrated effectiveness in the treatment of AUD. For example, a systematic review found that the community reinforcement approach combined with the medication disulfiram decreased the number of drinking days, but there was conflicting evidence of the impact of a community reinforcement approach on abstinence (Hunt and Azrin, 1973; Roozen et al., 2004). Studies have shown that CBT combined with naltrexone, alone or with acamprosate, is an effective treatment for

alcohol dependence (DSM-IV) (Anton et al., 2006; Feeney et al., 2006). However, the COMBINE study did not demonstrate any significant added effectiveness of the combination of naltrexone, acamprosate, and behavioral interventions (Anton et al., 2006). Another study found that while acamprosate was more effective in promoting abstinence, naltrexone had a slight advantage in reducing heavy drinking and craving, but this review did not examine the effect of the medications in conjunction with CBT (Maisel et al., 2013). The degree of effectiveness of CBT in combination with medications warrants further study, given the number of people with AUD and the consequences that can result from the disease for patients and the public.

Cost-Effectiveness of Treatment to Reduce Alcohol-Impaired Driving Crashes

The committee could not identify a study of alcohol treatment that specifically examined the cost-effectiveness related to alcohol-impaired driving crashes and/or fatalities as the single outcome. However, there are multiple studies of the cost-effectiveness of AUD treatment with respect to other outcomes, suggesting that AUD treatment can be cost-effective. Thus, while there are no studies evaluating whether AUD treatment is cost-effective when solely considering reducing alcohol-impaired driving crashes, there would likely be other important effects from AUD treatment to other socially desirable outcomes such that treatment could be cost-effective when considering a broader set of outcomes.