2

Regional Missile Threats to the Russian Federation and the United States

This chapter summarizes the general threat to international security from proliferation of missile technologies, with examples highlighting the current and prospective threats from the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, and the Islamic Republic of Iran. In selecting these states for analysis, the joint committees are making no judgments on the probability of future conflict. In terms of technical capabilities, however, intermediate- and medium-range ballistic missiles from all three states could present a physical threat to the territory of the Russian Federation as well as to U.S. allies and deployed U.S. forces. Today, several countries are developing missile programs. The three countries listed above are considered in this study because of the lack of transparency about these programs, and a lack of understanding about these countries’ policies and motivations as well as the possibility of future internal instability. These combined factors make these missile programs potential threats that may not be deterrable by classical means.

At the end of the chapter, the joint committees have summarized key efforts to limit and restrict missile proliferation, including the Missile Technology Control Regime, The Hague Code of Conduct against Ballistic Missile Proliferation, the Wassenaar Arrangement, and the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF Treaty).

MISSILES: A BRIEF OVERVIEW

The ability of missiles to strike from afar coupled with the difficulty of defending against missiles and of identifying launch sites for counterstrikes make missiles attractive tools for the militaries of large and small countries, and for non-state groups, such as the group calling itself the Islamic State in Iraq and Levant, or ISIL (Da’esh). The joint committees are especially concerned about missiles carrying nuclear explosives, chemical agents, or biological agents (weapons of mass destruction), but they may also carry conventional explosives, which remain a substantial concern.

This report addresses ballistic missiles, not cruise missiles. Ballistic missiles are boosted by a solid-fuel rocket motor or liquid-fuel rocket engines along a prescribed path until rocket motor burnout, which is the end of powered flight. After that point, the missile is unguided, so the missile follows a trajectory determined by gravity, atmospheric drag, and the momentum from its earlier powered flight. Cruise missiles are guided missiles that are powered throughout flight, usually by

a jet engine, and reach their target at far lower velocities than those of ballistic missiles. Some cruise missiles may have ranges of more than 5,500 km, but most have much shorter ranges (less than or equal to 2,500 km). Although both types of missile pose threats to international security, this report is focused on the threat from ballistic missiles.*

Missiles are also categorized by their flight range. Table 2-1 lists commonly used categories for these different ranges.

TABLE 2-1 Missile Types by Range

| Missile Type | Range in km with payloads of hundreds of kg |

|---|---|

| Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs) | >5,500 |

| Intermediate-Range Ballistic Missiles (IRBMs) | 1,000–5,500a |

| Medium-Range Ballistic Missiles (MRBMs) | 1,000–3,000 |

| Shorter-Range Ballistic Missiles | 500–1,000a |

| Short-Range Ballistic Missiles (SRBMs) | 70–500 |

| Submarine-Launched Ballistic Missiles (SLBMs) | Not normally characterized by range. All currently deployed SLBMs are designed for strategic targets similar to those held at risk by ICBMs. |

a These ranges are defined in the Treaty Between the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics on the Elimination of Their Intermediate-Range and Shorter-Range Missiles.

SOURCE: INF Treaty.

Although these range definitions are commonly used, they do not completely correspond with the definitions in the 1987 INF Treaty. That treaty bans land-based “intermediate-range missiles” with ranges between 1,000 and 5,500 km, and also bans land-based “shorter-range missiles” with ranges between 500 and 1,000 km. This study is limited to defense against intermediate- and medium-range missiles precisely because neither the United States nor the Russian Federation were allowed to possess them under the INF Treaty. Improving defenses against missiles the two states were prohibited from developing or deploying could, therefore, threaten neither state. For convenience, except where greater specificity is needed, this report will use the phrase “intermediate-range ballistic missiles” (IRBMs) as a synonym for “land-based ballistic missiles of ranges prohibited by the INF Treaty.”

The joint committees note that more countries possess ballistic missiles today than ever before, and several of them are working to improve their missiles or to acquire more advanced missiles from other countries. It is currently thought that at least 30 nations29 have ballistic missile capabilities,30 of which many have missiles with payloads large enough to deliver a Hiroshima-scale (i.e., 15 kt) explosive package.31 Most of these countries have only short-range ballistic missile capabilities. A small number of countries are confirmed to have deployed operational intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) with intercontinental range, although a number of other states may be working to develop these capabilities.† Although the United States and the Russian Federation have eliminated their

___________________

* Boost-glide vehicles—that is, those that use a ballistic missile for launch but maneuver aerodynamically upon reentry—are excluded from the joint committee’s analysis because they will not be deployed in the time frame under examination (2020 or just beyond).

† Countries with confirmed deployed, fully operational ICBMs are the United States, the Russian Federation, and the People’s Republic of China. North Korea has demonstrated missiles with intercontinental range and apparently

medium-range ballistic missiles and IRBMs under the INF Treaty, most countries with ballistic missile ambitions have only increased the numbers and ranges of their missiles over time, and the number of countries with ballistic missiles continues to grow. Furthermore, missile capabilities are being enhanced by achieving longer ranges and greater accuracy by utilizing mobile launchers, and through greater defense of the missiles themselves. All of these factors make ballistic missiles serious threats to be considered by both the Russian Federation and the United States.

THREATS FROM INTERMEDIATE- AND MEDIUM-RANGE MISSILES: ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF PAKISTAN, DEMOCRATIC PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF KOREA, AND ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF IRAN

The United States has identified missile threats to U.S. allies from North Korea and Iran as the mission for U.S. regional defense. The U.S. European Phased Adaptive Approach (EPAA) has been described by U.S. officials as designed to defend the European members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) from Iranian ballistic missiles.32 Russia borders North Korea and nearly borders Iran. Russia also faces the possibility of missile threats from neighbors and near neighbors along its southern border. Current Pakistani, North Korean, and Iranian missile programs are at different stages of development, particularly with regard to the potential for nuclear payloads, ranging from a significant nuclear arsenal to a small nuclear capability to a latent nuclear capability. The People’s Republic of China, the Republic of India, and the State of Israel also have medium-range missiles capable of reaching the territory of the Russian Federation or U.S. allies. India and Israel were deemed by the joint committees not to threaten either the Russia Federation or U.S. allies. China is potentially a threat to both the United States and the Russian Federation, but the joint committees deemed it unproductive to include detailed analysis of their missile capabilities because neither U.S. nor Russian missile defense have been characterized by the respective governments as explicitly deployed to counter Chinese threats. Chinese missiles are more numerous and sophisticated than those of Pakistan, North Korea, and Iran, and the Chinese regime is less prone to unpredictable escalatory actions. Further, relations among the United States, Russia, and China raise complex strategic stability issues beyond the scope of this report.

As a result, the joint committees selected missile threats from Pakistan, North Korea, and Iran for detailed analysis. The threats were deemed (a) realistic because of the countries’ missile capabilities (having limited numbers of IRBMs) and the unpredictability of their governments, and (b) representative of the types of threats that could be addressed through potential ballistic missile defense collaboration. These three countries’ missiles are described in Table 2-2.

___________________

deployed them in its arsenal. Tests have not conclusively indicated their ability to accurately and consistently reach their intended targets. India has developed and tested intercontinental-range missiles. Israel’s Jericho-3 missile is thought by some to be able to exceed the intermediate-range SLBMs of France and the United Kingdom. Indian and Israeli missiles have similar missions to ICBMs, and North Korea and India are developing SLBMs.

TABLE 2-2 Estimated Ballistic Missile Capabilities of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), and the Islamic Republic of Iran as of 2017

| Country | Missile | Stages | Fuel | Launch Gross Weight (kg) | Empty Weight (kg) (Without Warhead) | Full Weight (kg) (Without Warhead) | Structure Factor | Residual Fuel | Specific Impulse (sec) Sea Level / Vacuum | Burnout Time (s) | Burnout Velocity (km/s) | Payload (kg) | Operating Range (km) | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pakistan | Hatf 1 | Solid | 500 | 50-100 | Operational | |||||||||

| Pakistan | Hatf 2 (Abdali) | Solid | 180-450 | 180-200 | Operational | |||||||||

| Pakistan | Hatf 2A (Abdali) | Solid | 500 | 180-300 | Operational | |||||||||

| Pakistan | Hatf 3 (Ghaznavi) | Solid | 700 | 250-400 | Operational | |||||||||

| Pakistan | Hatf 4 (Shaheen 1) | Solid | 700-800 | 750-900 | Operational | |||||||||

| Pakistan | Hatf 5 (Ghauri 1) | 1 | Liquid | 15,200 | 1,800 | 14,200 | 0.13 | 0.04 | 220/247 | 98 | 3.4 | 500-1,200 | 950-1,800 | Operational |

| Pakistan | Hatf 5 (Ghauri 3) | Unknown | 1,300 | Development | ||||||||||

| Pakistan | Hatf 5A (Ghauri 2) | 700-1,200 | 1,500-1,800 | Operational | ||||||||||

| Pakistan | Hatf 6 (Shaheen 2) | 2 | Solid | 264/278 | 700-1,000 | 2,000-2,500 | Operational | |||||||

| Pakistan | Hatf 9 (Nasr) | Solid | 400 | 60-120 | Tested | |||||||||

| Pakistan | Shaheen 3 | 2 | Solid | Unknown | 2,750 | Tested | ||||||||

| Pakistan | Ababeel | Unknown | 2,200 | Tested | ||||||||||

| North Korea | KN-02 (SS-21 variant; Toksa) | Solid | 120-500 | 100-220 | Operational | |||||||||

| North Korea | Hwasong 5 (Scud B) | 1 | Liquid | 5,900 | 1,100 | 4,900 | 0.23 | 0.05 | 230/253 | 985-1,000 | 300-320 | Operational |

| Country | Missile | Stages | Fuel | Launch Gross Weight (kg) | Empty Weight (kg) (Without Warhead) | Full Weight (kg) (Without Warhead) | Structure Factor | Residual Fuel | Specific Impulse (sec) Sea Level / Vacuum | Burnout Time (s) | Burnout Velocity (km/s) | Payload (kg) | Operating Range (km) | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North Korea | Hwasong 6 (Scud C) | 1 | Liquid | 6,400 | 1,100 | 5,400 | 0.2 | 0.05 | 230/253 | 700 | 500 | Tested | ||

| North Korea | Hwasong 7 (Scud D) | Liquid | 400-750 | 700-1,000 | Operational | |||||||||

| North Korea | Extended-range Scud | 1 | Liquid | Unknown | 1,000 | Unknown | ||||||||

| North Korea | Bukkeukseong-2 | 2 | Solid | Unknown | 1,000+ | Development | ||||||||

| North Korea | No Dong Mod 1/2 | 1 | Liquid | 15,200 | 1,800 | 14,200 | 0.13 | 0.04 | 220/247 | 98 | 3.4 | 250-1,200 | 1,200-1,500 | Operational |

| North Korea | Hwasong-10 (Musudan, No Dong B) | Liquid | 500-1,200 | 2,500-4,000 | Operational | |||||||||

| North Korea | Hwasong-12 (KN-17) | 1 | Liquid | 500 | 3,000-4,500 | Tested | ||||||||

| North Korea | Taepodong1 (Moksong 1) | 3 | Solid / Liquid | 100-200 | 2,000-5,500 | Operational | ||||||||

| North Korea | Taepodong2 (Moksong 2, Unha-2) | 3 | Liquid | 100-1,000 | 3,500-12,000 | Development | ||||||||

| North Korea | Taepdong-3 (Unha-3) | 3 | Liquid | 100-1,000 | 5,500-12,000+ | Development | ||||||||

| North Korea | KN-08 (Hwasong 13)a | 3 | Liquid | 300-700 | 5,000-11,500 | Development | ||||||||

| North Korea | Hwasong-14a | 2 | Liquid | 100-1,000 | 5,500-10,400 | Development | ||||||||

| North Korea | Hwasong-15 | 2 | Unknown | 8,500-13,000 | Tested |

| Country | Missile | Stages | Fuel | Launch Gross Weight (kg) | Empty Weight (kg) (Without Warhead) | Full Weight (kg) (Without Warhead) | Structure Factor | Residual Fuel | Specific Impulse (sec) Sea Level / Vacuum | Burnout Time (s) | Burnout Velocity (km/s) | Payload (kg) | Operating Range (km) | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North Korea | KN-11 (Pukgukson g-1) | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | ||||||||||

| North Korea | KN-15 (Pukgukson g-2) | Solid | Unknown | Unknown | Tested | |||||||||

| Iran | Fateh 110 (Mershad) | 1 | Solid | 300-600 | 170-300 | Operational | ||||||||

| Iran | Tondar 69 (CSS-8) | 1 | Solid | 190-210 | 50-180 | Unknown | ||||||||

| Iran | Qiam-1 | Liquid | Unknown | 800 | Unknown | |||||||||

| Iran | Shahab-1 (Scud B variant) | 1 | Liquid | 5,900 | 1,100 | 4,900 | 0.23 | 0.05 | 230/253 | 985 | 300-315 | Operational | ||

| Iran | Shahab-2 (Scud C variant) | 1 | Liquid | 6,400 | 1,100 | 5,400 | 0.2 | 0.05 | 230/253 | 730-770 | 375-500 | Operational | ||

| Iran | Shahab-3 (based on No Dong) | 1 | Liquid | 15,200 | 1,800 | 14,200 | 0.13 | 0.04 | 220/247 | 98 | 3.4 | 760-1,200 | 800-2,000 | Operational |

| Iran | Emad-I (modified Shahab 3) | 1 | Liquid | Unknown | Up to 2,000 | Unknown | ||||||||

| Iran | Ghadr-1 (modified Shahab 3) | 1 | Liquid | 98 | 3.7 | 750 | 1,500-2,500 | Tested | ||||||

| Iran | Shahab-4 | Unknown | 2,000-3,000 | Development | ||||||||||

| Iran | Shahab-5 | 2 or 3 | Unknown | 1,000-4,000+ | Development | |||||||||

| Iran | Shahab-6 | 2 or 3 | Liquid / Solid | Unknown | 6,000+ | Development |

| Country | Missile | Stages | Fuel | Launch Gross Weight (kg) | Empty Weight (kg) (Without Warhead) | Full Weight (kg) (Without Warhead) | Structure Factor | Residual Fuel | Specific Impulse (sec) Sea Level / Vacuum | Burnout Time (s) | Burnout Velocity (km/s) | Payload (kg) | Operating Range (km) | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iran | Safir (Musudan) | 2 | Liquid | 188 | 5.5 | 2,000 | 3,500 | Unknown | ||||||

| Iran | Zelzal 1/2/3 | Unknown | 125-400 | Operational | ||||||||||

| Iran | Sejjil (Sajjil, Ashura, 2 stage, aka Sajjil 2) | 2 | Solid | 72 | 3.8 | 750-1,000 | 2,000-3,000 | Development | ||||||

| Iran | Khorramsha hr (modified Safir) | Liquid | Unknown | 1,000+ | Tested |

a The sources referenced here are inconsistent regarding the analysis as to whether or not the Hwasong-13 and the Hwasong-14 missiles are one and the same or different missiles. They are listed separately here for greater transparency. See Kristensen and Norris, 2018 and Schilling, 2017.33

NOTE: All specifications are approximate for analysis; no classified information was used. In general, this and other tables in this report refer to the most recent reliable information where an updated and reliable resource was available. If multiple sources provided varying ranges for the same missile type, the joint committees have provided the lowest and highest referenced ranges (km). Additionally, given the lack of transparency about these missile programs, where reliable sources provided inconsistent information about the status of specific missile development, the joint committees have included the earliest referenced status along the spectrum from “in development” to “deployed.”

SOURCES: Arbatov and Dvorkin (eds.) 2013a; Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation, 2017; CNS and NTI, 2014; CNS and NTI, 2016; Davenport, 2018; Elleman, 2013; FAS, 2016; Grisafi, 2014; Hildreth, 2012; Nagappa, R. et al., 2014; NASIC and DIBMAC, 2017; NTI, 2013; NTI, 2015a; NTI, 2016a; NTI, 2016b; NTI, 2017a; NTI, 2017b; NTI, 2019; Postol, 2009; Sankaran, 2014; Schiller and Schumucker, 2013; Schilling and Kan, 2015. See reference.34

Pakistan

Currently, Pakistan possesses the following missiles (see Table 2-3):

- the Ghauri 1 and 2 liquid-propellant missiles, with a range of 1,300 to 1,800 km; and

- the Shaheen 2/Hatf 6 two-stage, solid-propellant missile, with a range of 2,000–2,500 km with a 700–1,000 kg payload.

TABLE 2-3 Summary of Pakistani Ballistic Missile Characteristics

| Missile | Warhead, payload (kg) | Operating range (km) | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hatf 1 | 500 | 50–100 | Operational |

| Hatf 2 (Abdali) | 180–450 | 180–200 | Operational |

| Hatf 2A (Abdali) | 500 | 180–300 | Operational |

| Hatf 3 (Ghaznavi) | 700 | 250–400 | Operational |

| Hatf 4 (Shaheen 1) | 700–800 | 750–900 | Operational |

| Hatf 5 (Ghauri 1) | 700–1,200 | 950–1,800 | Operational |

| Hatf 5A (Ghauri 2) | 700–1,200 | 1,500–1,800 | Operational |

| Hatf 5 (Ghauri 3) | Unknown | 1,300 | Development |

| Hatf 6 (Shaheen 2) | 700–1,000 | 2,000–2,500 | Operational |

| Hatf 9 (Nasr) | 400 | 60–120 | Tested |

| Shaheen 3 | Unknown | 2,750 | Tested |

SOURCES: Arbatov, A., and V. Dvorkin (eds.) 2013a; Nagappa, R. et al. 2014; NTI and CNS 2014; NASIC and DIBMAC 2017; Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI) 2015; Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI) 2016a; Sankaran 2014. See reference.35

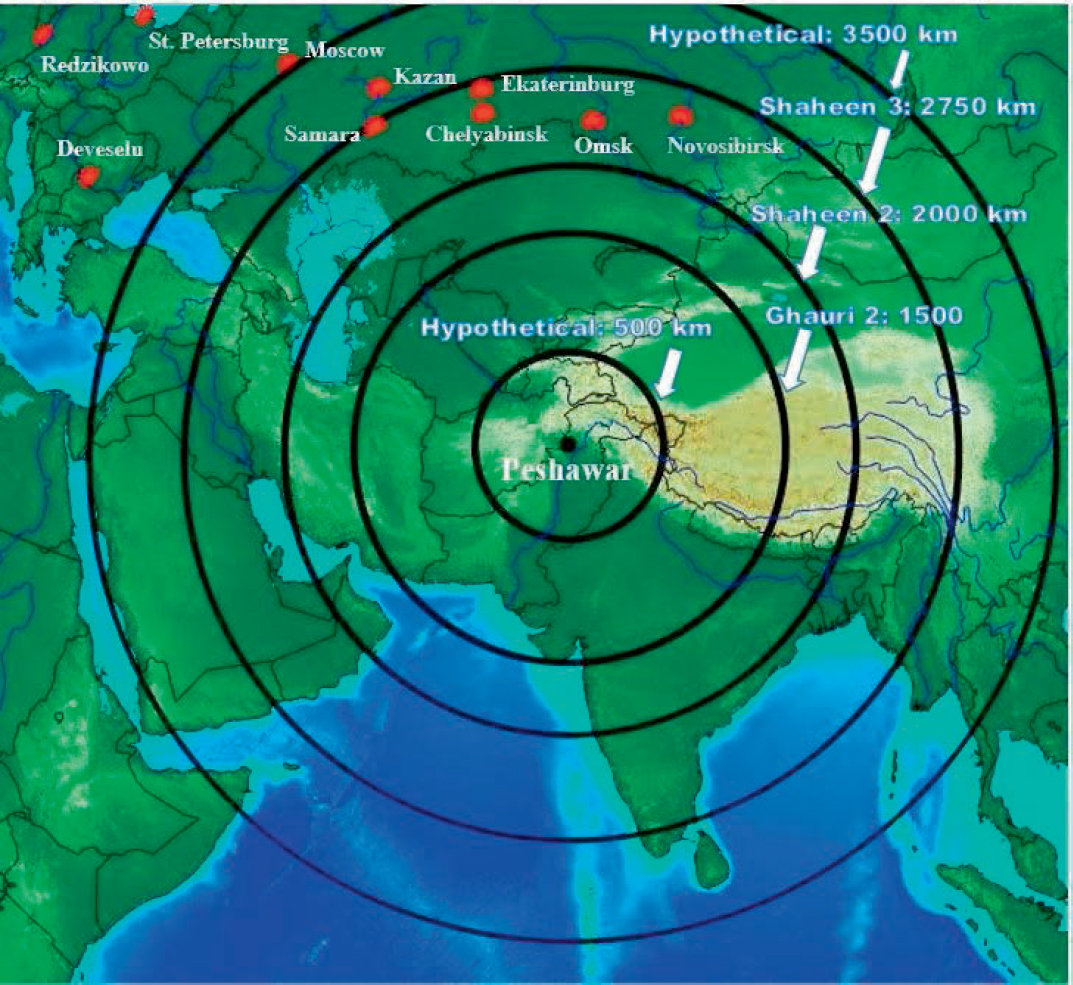

Pakistan maintains a ballistic missile arsenal as its primary strategic delivery vehicle targeting India. The Hatf series, which includes the Ghaznavi, Shaheen, and Ghauri ballistic missiles, carry single-warhead payloads at operating ranges from the short-range Hatf-1 and Nasr missiles (50–120 km) to the medium-range Shaheen 2 (2,000–2,500 km; see Table 2-3).36 Until the early 2000s, Pakistan reportedly had been developing the Ghauri 3 with a projected range of 3,000–3,500 km, but the program appears to have been cancelled because it is not in development.37 In late 2015, Pakistan tested a 2,750 km range Shaheen 3 missile (see Figure 2-1).38 Although Pakistan’s decision-making processes are not fully understood, posing a potential concern, competition with India will likely drive continued ballistic missile development, and so Islamabad has no present reason to develop longer-range missiles capable of reaching Moscow or U.S. allies in Europe.39

SOURCE: Created by J. Sankaran, consultant, 2016.

North Korea

The secrecy of North Korea’s missile development program and relative dearth of live-fire testing for many years renders the North Korean missile threat inherently difficult to predict.* Official government reports, as well as open-source analyses, yielded varied estimates for North Korean missile ranges, capabilities, and intentions, particularly as to the country’s long-range ballistic missile program.

___________________

* Miller, J. April 20, 2010, Hearing of the Senate Armed Services Committee, available at https://www.mda.mil/global/documents/pdf/ps_sasc042010trans.pdf, accessed on January 24, 2019. North Korea significantly increased its missile test activities in 2016 and 2017. North Korea clearly has missiles now with much longer ranges. The implications of these new capabilities have not been assessed fully.

More uniformly understood are North Korea’s short-range ballistic missile systems, with operational capacity to reach targets in South Korea and Japan.40 Reverse-engineered and extended from the Soviet Scud B, Scud C, and Scud D missiles, the Hwasong 5, Hwasong 6, and Hwasong 7 missiles have maximum ranges of 300-320 km, 500 km, and 700–1,000 km, respectively (see Table 2-4). An even shorter range (100–160 km) ballistic missile, the KN-02 Toksa, based on the Soviet SS-21 Tochka, has been reported by the U.S. National Air and Space Intelligence Center (NASIC) as operational.41 NASIC also cites an extended range (700–1,000 km) Scud variant under development;42 it may have also been tested.43

TABLE 2-4 Summary of North Korean Ballistic Missile Characteristics

| Missile | Warhead, payload (kg) | Operating range (km) | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| KN-02 (SS-21 variant; Toksa) | 120–500 | 100–160 | Operational |

| Hwasong 5 (Scud B) | 985–1,000 | 300–320 | Operational |

| Hwasong 6 (Scud C) | 700 | 500 | Tested |

| Hwasong 7 (Scud D) | 400–750 | 700–1,000 | Operational |

| Extended-range Scud | Unknown | 1,000 | Unknown |

| Bukkeukseong-2 | Unknown | 1,000+ | Development |

| No Dong Mod 1/2 | 250–1,200 | 1,200–1,500 | Operational |

| Hwasong-10 (Musudan-1, BM-25, No Dong B) | 500–1,200 | 2,500–4,000 | Operational |

| Hwasong-12 (KN-17) | 500 | 3,000–4,500 | Tested |

| Taepodong-1 (Moksong 1) | 100–200 | 2,000–5,500 | Operational |

| Taepodong-2 (Moksong 2, Unha-2) | 100–1,000 | 3,500–12,000 | Tested |

| Taepodong-3 (Unha-3) | 100–1,000 | 5,500–12,000 | Operational |

| KN-08 (Hwasong 13) a | 300–700 | 5,000–11,500 | Development |

| Hwasong-14 a | 500 | 5,500+ | Tested |

| Hwasong-15 | Unknown | 8,500–13,000 | Tested |

| KN-11 (Pukguksong-1) | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| KN-15 (Pukguksong-2) | Unknown | Unknown | Tested |

a The sources referenced here are inconsistent regarding the analysis as to whether or not the Hwasong-13 and the Hwasong-14 missiles are one and the same or different missiles. They are listed separately here for greater transparency. See relevent references in Table 2-2 above.

SOURCES: Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation 2017; CNS and NTI 2016; Davenport 2018; FAS 2016; Grisafi 2014; NASIC and DIBMAC 2017; NTI 2016b; NTI 2017a; NTI 2019; Schiller and Schumucker 2013; Schilling and Kan 2015.44

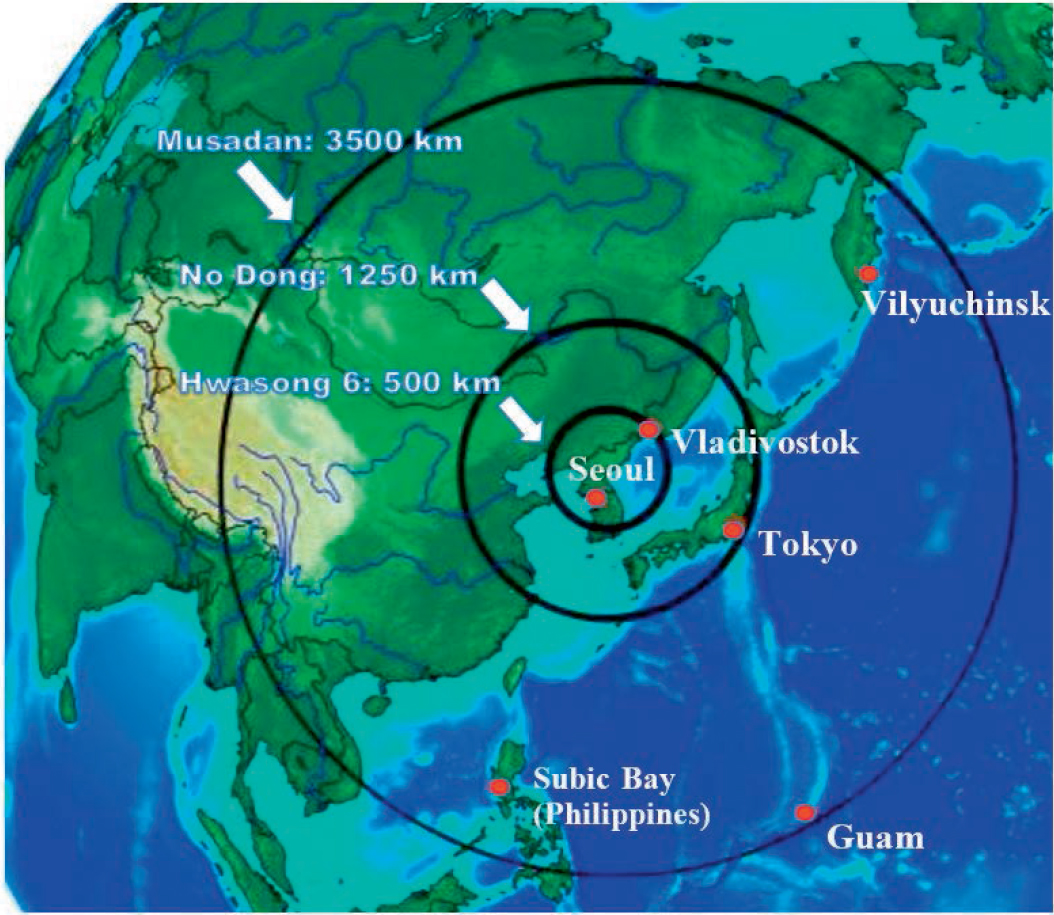

At the medium range, the No Dong Mod 1/2 missile is reported operational with a range of 1,200–1,500 km (see Figure 2-2). The Bukkeukseong-2, with a similar range, is reportedly not yet deployed.

At a range capable of targeting U.S. military bases in Guam and/or potentially parts of the western United States are four tested platforms: the Hwasong-12, the Hwasong-14, the Taepodong-2, and the Hwasong-15. The Hwasong-12 and Hwasong-14 (apparently a two-stage version of the Hwasong-12) were flight tested in 2017. Taepodong-2, a two- or three-stage missile

(ICBM, which serves as the base rocket for the Unha space launch vehicle), has been tested with varying results, but a modification of this missile, the Unha-3 rocket, succeeded in placing a satellite into orbit in December 2012,45 and again in February 2016.46

Of uncertain status is the KN-08 or Hwasong-13, a road-mobile ICBM initially displayed in a 2012 North Korean military parade; some analysts have found evidence suggesting that the Hwasong-13 and Hwasong-14 are in fact the same system. While the missile has apparently never been flight tested, in April 2015, the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD)/U.S. Northern Command (NORTHCOM) Commander Admiral William Gortney stated that the KN-08 was operational and capable of fielding a small nuclear payload.47 North Korea’s ballistic missile tests in 2017 indicate its accelerated timeline of ICBM development, which may already provide North Korea with the capability of reaching U.S. territory, although the ability to accurately and consistently target these missiles is unknown.48

SOURCE: Created by J. Sankaran, consultant, 2016.

Iran

Iran maintains the largest and most diverse ballistic missile arsenal in the Middle East and continues to pursue a dual-track approach to domestic production (see Table 2-5).49,50 In one track, Iran has adapted Scud-based, liquid-fueled systems to field the majority of its operational arsenal; the second track seeks to leverage Chinese solid-fuel technology. At the center of Iran’s ballistic arsenal is its Shahab series—the Shahab-1, Shahab-2, and Shahab-3—based on the Scud B, the Scud C, and the North Korean No Dong missile, respectively. The Shahab-3 can carry a single warhead payload up to approximately 2,000 km, putting Iraq, Afghanistan, and the western portion of Saudi Arabia in range.

TABLE 2-5 Summary of Iranian Ballistic Missile Characteristics

| Missile | Payload (kg) | Operating range (km) | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fateh-110 (Mershad) | 300–600 | 170–300 | Operational |

| Tondar 69 (CSS-8) | 190–210 | 50–180 | Unknown |

| Qiam-1 | Unknown | 800 | Unknown |

| Shahab-1 (Scud B variant) | 985 | 300 | Operational |

| Shahab-2 (Scud C variant) | 730–770 | 500 | Operational |

| Shahab-3 (based on No Dong) | 760–1,200 | 800–2,000 | Operational |

| Emad-I (modified Shahab 3) | Unknown | Up to 2,000 | Unknown |

| Ghadr-1 (modified Shahab 3) | 750 | 1,500–2,500 | Tested |

| Shahab-4 | Unknown | 2,000–3,000 | Development |

| Shahab-5 | Unknown | 1,000–4,000+ | Development |

| Shahab-6 | Unknown | 6,000+ | Development |

| Safir (BM-25) | 2,000 | 3,500 | Unknown |

| Zelzal 1/2/3 | Unknown | 125–400 | Operational |

| Sejjil (Sajjil, Ashura, 2 stage, aka Sajjil 2) | 750–1,000 | 2,000–3,000 | Development |

| Khorramshahr (modified Musudan) | Unknown | 1,000+ | Tested |

SOURCES: Arbatov and Dvorkin (eds.), 2013, 281-285; Elleman, 2013; Hildreth, 2012; NASIC and DIBMAC, 2017; NTI, 2013; NTI, 2017b; Postol, 2009; Sankaran, 2014, 53.51

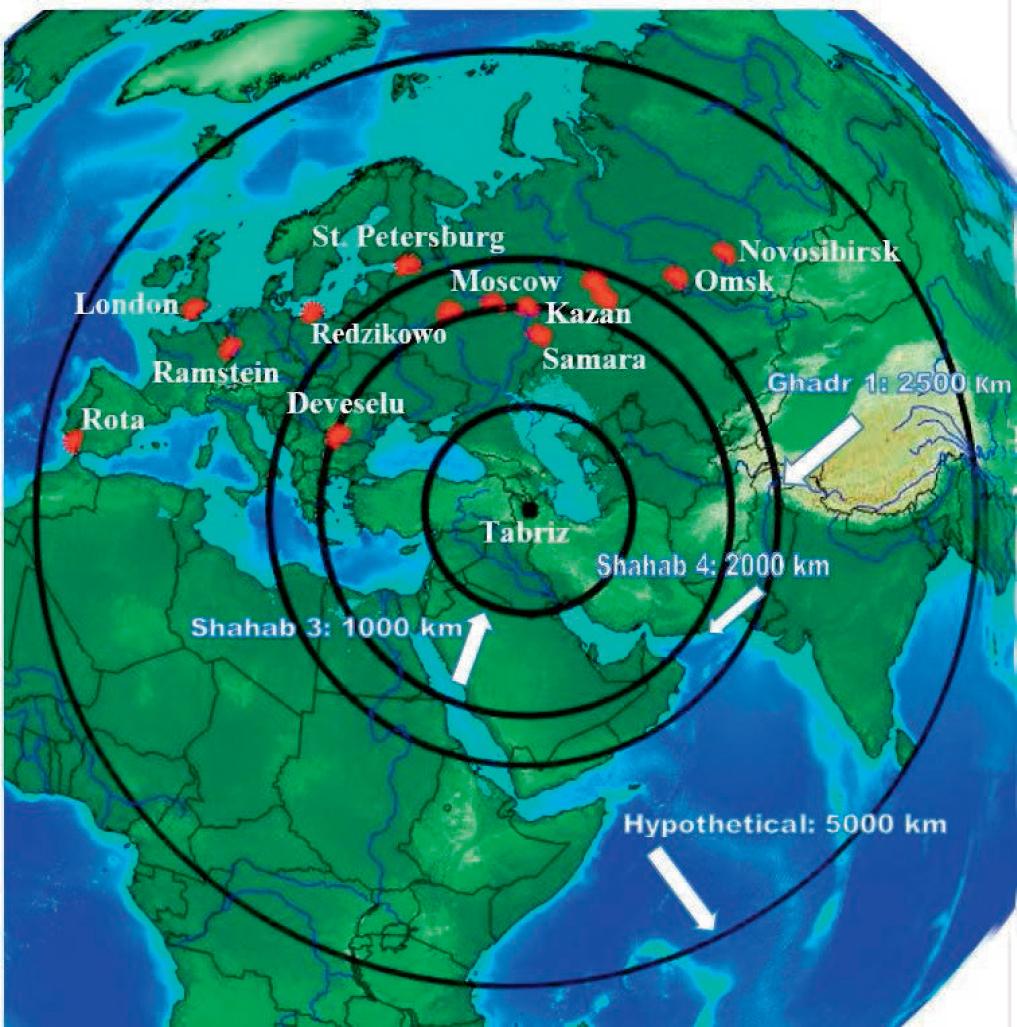

Falling just short of the operating range requirements to target Israel, the Shahab-3 was modified and tested in 2004. That same year the Ghadr-1 was modified and tested as well, with a maximum range reported from 1,500 to 2,500 km. Both Israel and portions of southeastern Europe are now in range of the Ghadr-1 (see Figure 2-3).52 With a 750 kg payload, this missile can inflict substantial damage. Further modification of this missile is of questionable benefit to gaining longer range.

Also in development at the medium range is Iran’s Sejjil, a two-stage, solid-fuel missile tested five times with mixed results, and potentially capable of reaching as far as Italy and Poland with its expected 2,000+ km operating range. The Sejjil-2 intermediate-range solid-propellant missile, with a range of 2,000–3,000 km with a 750–1,000 kg payload, has been developed and tested.53 Modified alternatives of this missile are possible by 2020, with improved missile body design resulting from the use of lighter alloys and the use of composite materials, as well as the

development of a three-stage version of the missile. Should this occur, the missile’s range could have a maximum range of 4,000 km.54

Of note is Iran’s space development program with possible relevance to Iran’s missile program, which since 2009 has successfully placed four satellites into orbit on the Safir launch vehicle. While estimates, including from the Indian National Institute of Advanced Studies, suggest that the two-stage Safir space launch vehicle might readily be converted into a two-stage missile with a 2,400 km range and 1,000 kg payload,55 deploying a nuclear-capable ICBM from this technology may be more difficult than the satellite launches to date. The Safir launch vehicle is capable of launching spacecraft weighing 25–50 kg. If the second stage of the Safir design were reinforced, some analysts think that the rocket could be converted into a ballistic missile with a range of 4,500–5,000 km. The Simorgh launch vehicle is expected to be capable of launching spacecraft weighing up to 100 kg, which some say could be made into an ICBM, although there are several challenges involved in converting a space launch vehicle into a militarily significant ICBM.

Both the U.S. National Air and Space Intelligence Center and Russian experts report the development of Iranian longer-range IRBM or ICBM capabilities, but little is openly known about program details and missile specifications. The time frame for development of an Iranian ICBM capable of reaching the east coast of the United States (9,000 km away) is uncertain, with estimates ranging from within 1 or 2 years to more than a decade away.56

Implications of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action

In July 2015, China, France, Germany, Iran, the Russian Federation, the United Kingdom, and the United States agreed on a Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA)57 to deal with international concerns over the Iranian nuclear program. The program included undeclared centrifuge uranium enrichment facilities, constructed in violation of obligations under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty,58 that could have enabled Iran to generate enough highly enriched uranium to develop a nuclear explosive in far less than 1 year. It also included a heavy water irradiated reactor that could have been used to generate plutonium for use in a nuclear explosive.

This agreement, designed to mitigate these perceived threats, has caused the Russian Federation to question the continued need for the planned U.S. EPAA to defend NATO territory against Iranian ballistic missiles. For example, in July 2015, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov said: “We all remember when in April 2009, in Prague, President [Barack] Obama said that if the Iranian nuclear issue was settled, there would be no need in creating an air defense system in Europe.”* The United States has stated that it does not intend to cancel EPAA, and has not provided a detailed rationale for this decision. The apparent rationale is that the JCPOA does not prevent ongoing Iranian ballistic missile development, which is continuing despite United

___________________

*Sputnik, updated July 15, 2015, “Lavrov Reminds U.S.: European Missile Defense Needless as Iran Deal Reached,” available at https://sptnkne.ws/k7XA, accessed on January 17, 2019. Lavrov had misquoted U.S. President Barack Obama’s remarks in Prague, Czech Republic. President Obama had stated, “So let me be clear: Iran’s nuclear and ballistic missile activity poses a real threat, not just to the United States, but to Iran’s neighbors and our allies. The Czech Republic and Poland have been courageous in agreeing to host a defense against these missiles. As long as the threat from Iran persists, we will go forward with a missile defense system that is cost-effective and proven. If the Iranian threat is eliminated, we will have a stronger basis for security, and the driving force for missile defense construction in Europe will be removed.” The speech can be read in full at The White House, April 5, 2009, “Remarks of President Barack Obama,” available at https://www.armscontrol.org/ObamaPragueSpeech, accessed on January 18, 2019.

SOURCE: Created by J. Sankaran, consultant, 2016.

Nations Security Council Resolutions 192959 and 2231.60 Moreover, as Iranian rockets become more accurate, they may become—even with conventional warheads—capable of hitting civilian nuclear facilities such as power plants and research reactors. As certain economic sanctions are lifted as a result of the JCPOA, Iran is predicted to have more funds available potentially for missile development. Further, according to the terms of the agreement, the ballistic missile–related sanctions are to end 8 years after Adoption Day or when the International Atomic Energy Agency

reports that all of Iran’s nuclear materials remain in peaceful activities, whichever is sooner, giving Iran additional opportunity for missile development.*

The goal of the JCPOA is to ensure that Iran cannot produce a nuclear weapon in less than 1 year from the time that a decision is taken to do so.† This is far shorter than the time needed to resume deployment of EPAA beyond the third phase. When these facts are coupled with skepticism about Iran’s compliance (based on past behavior and the status of the JCPOA) and with the reality that the agreement does not (and cannot) permanently preclude Iranian weapons development, the United States believes continued maturation of defenses against Iranian intermediate- and medium-range missiles is prudent. The joint committees acknowledge that this remains one of many points of contention between the Russian Federation and the United States, but do not believe it invalidates the arguments for cooperation made elsewhere in this report.

MISSILE NONPROLIFERATION REGIMES

In response to the growing threat of ballistic missiles over the years, various export-control regimes have been established to limit the proliferation of missile technologies around the world (see Table 2-6). These are politically binding agreements among willing nations rather than formal treaties, and represent the primary international mechanism by which ballistic missile proliferation is currently constrained.61

The sole existing treaty that actually limited ballistic missiles applied only to the Russian Federation and United States. The INF Treaty of 198762 outlawed either country from having ground-launched ballistic or cruise missiles with ranges of 500 to 5,500 km. Although the intent was to curtail nuclear weapon-tipped missiles, the INF Treaty was broadly applicable to weapons delivery vehicles regardless of payload if they had demonstrated these ranges.

The most widely applicable export-control regimes specifically addressing ballistic missile technologies are the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR) of 1987, which was then generalized to The Hague Code of Conduct against Ballistic Missile Proliferation (HCoC) in 2002. The MTCR, with 35 members as of 2004, is intended to curb transfer of technologies for unmanned delivery of nuclear weapons—specifically, of payloads exceeding 500 kg delivered to ranges greater than 300 km. The HCoC is a multilateral transparency agreement restraining proliferation of ballistic missiles that has 139 signatories to date.

Finally, the Wassenaar Arrangement of 1996, with 42 members, supports export controls of a wide variety of conventional arms and dual-use goods and technologies, including those associated with ballistic missiles. The United States and the Russian Federation are parties to all three of these regimes (MTCR, HCoC and Wassenaar); China, Iran, Israel, North Korea, and Pakistan are not formal members of these regimes at present, though some (e.g., China and Israel) are informally adhering to the export-control restrictions or are actively seeking membership in the regimes.

___________________

* At the time that this report went to print, the signators to the JCPOA had divergent views as to how to proceed.

† One year is an otherwise unconstrained technical timeline, but the purpose of the 1-year delay is to be able to take effective action to prevent the production of a nuclear weapon, including the use of force.

TABLE 2-6 Ballistic Missile Nonproliferation Regimes to Which the Russian Federation and United States Are Parties

| Name | Intent | Establishment | Exceptions | URL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR) | Curb transfer of technology for unmanned delivery of nuclear weapons: payload > 500 kg to > 300 km range | Originated in 1987 35 members as of 2004 |

Iran, Israel, North Korea, Pakistan; China, informally | http://www.mtcr.info/ |

| Hague Code of Conduct against Ballistic Missile Proliferation (HCoC) | Multilateral transparency agreement restraining proliferation of ballistic missiles | Established in 2002 139 signatories to date |

China, Iran, Israel, North Korea | http://www.hcoc.at/ |

| Wassenaar Arrangement | Export controls on conventional arms and dual-use goods and technologies | Established in 1996 42 members |

Iran, North Korea, Pakistan; China, Israel informally; India requesting | http://www.wassenaar.org/ |

In addition, United Nations Resolution 1540 (unanimously adopted in 2004) obliges all United Nations member states to adopt legislation “to prevent the proliferation of nuclear, chemical and biological weapons, and their means of delivery, and establish appropriate domestic controls over related materials to prevent their illicit trafficking.”63 The Australia Group (42 members as of 2013)* and Nuclear Supplier’s Group (48 members as of 2014, including China)† are additional regimes focused on biological and chemical weapons proliferation and on nuclear weapons proliferation, respectively.

___________________

* For information on the Australia Group, visit the website: The Australia Group (AG), available at https://australiagroup.net/en/, accessed on October 23, 2018.

† For information on the Nuclear Suppliers Group, visit the website: Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG), updated 2018, available at http://www.nuclearsuppliersgroup.org/en/, accessed on January 22, 2019.