4

Ballistic Missile Defense in the Absence of Cooperation

The decision to cooperate on ballistic missile defense (BMD) is not, in its essence, a technical decision, although there is a significant technical component to implementation of such a decision. Rather, such cooperation is a strategic decision, based on both the benefits expected from cooperation and the overall political relationship between the countries involved. States that view one another as allies or face a common enemy are more likely to be willing to cooperate in any relevant military mission, including BMD. In contrast, if states regard one another as enemies or as potential threats, then cooperation, while still possible, requires far more significant benefits to overcome barriers to cooperation and greater clarity about those benefits. Above all, such cooperation must not disadvantage either party.

To understand the effect of independent U.S. and Russian BMD systems on each country’s strategic deterrent, the joint committees have examined the impact of each system on the strategic forces of the other. The results are presented in Appendix C and show that planned U.S. regional BMD deployments have a negligible effect on Russian strategic retaliatory capability. This confirms statements by Russian officials that current and planned U.S. regional missile defense cannot prevent a major attack or counterstrike by Russian intercontinental ballistic missiles or submarine-launched ballistic missiles.* Subsequent chapters assess whether any of the cooperation the joint committees considered would alter this fact.†

___________________

* In March 2018, Russian President Vladimir Putin addressed the Duma on the military and defense capabilities of Russia. He stated, “We started to develop new types of strategic arms that do not use ballistic trajectories at all when moving toward a target and, therefore, missile defence systems are useless against them, absolutely pointless.” (The Kremlin, March 1, 2018, “Presidential Address to the Federal Assembly,” available at http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/56957, accessed on January 22, 2019.) The speech built upon previous statements and policy from Russian government officials. “‘The existing and would-be system of U.S. national missile defense cannot be impregnable to Russia’s Strategic Missile Troops,’ Commander Col. Gen. Sergey Karakayev told reporters on Wednesday. ‘Experts’ assessments prove that the current deployed system of the missile defense, according to its information and fire capabilities, cannot be impregnable to a massive impact by the group of Russia’s Strategic Missile Forces,’ Karakayev said ahead of Day of Strategic Missile Forces.” (TASS, December 16, 2015, “Officer: U.S. missile defense unlikely to be impregnable to Russian Strategic Missile Forces,” available at http://tass.com/defense/844547, accessed on October 31, 2018.)

† Because the Russian Federation does not deploy missile defenses outside its territory, no reciprocal analysis of the effect on U.S. strategic forces was necessary.

Despite the hopes of both states at the end of the Cold War, today many in Russia and the United States regard each other at least as threats and possibly as enemies.* The two countries’ strategic relations are based, at least in part, on the continued relevance of nuclear deterrence. As a result, ballistic missile defense cooperation is unlikely unless both countries agree that (a) it will result in actual military benefits for each country, and (b) it will not increase the ability of either country to threaten the other relative to the defenses of the other. As yet, the two governments have not been sufficiently convinced of either precondition to make a serious attempt at cooperation.

The logical result of the strategic context described above is no cooperation on ballistic missile defense. This chapter describes the result. Chapters 5 and 6 review options for cooperation should the strategic situation between the United States and the Russian Federation improve.

EFFECTIVENESS OF INDEPENDENT BALLISTIC MISSILE DEFENSE SYSTEMS

To evaluate the hypothetical effectiveness of the separate Russian Federation and U.S. regional ballistic missile defenses against perceived threats from Pakistan, North Korea, and Iran, the joint committees have used representative burnout velocities of both the attack missiles and deployed and/or planned interceptor missiles described in Chapters 2 and 3. The joint committees also considered kinematic capability, which is whether the interceptor has sufficient time to physically intercept the attack missile along its trajectory.† At least initially, the joint committees

___________________

* For a Russian perspective, see the December 2014 Russian Military Doctrine (for the English translation, see The Kremlin, 2014, Military Doctrine of the Russian Federation, available at https://www.offiziere.ch/wp-content/uploads-001/2015/08/Russia-s-2014-Military-Doctrine.pdf, accessed on January 22, 2019; for the Russian original, see: Voennaia doktrina Rossiiskoi Federatsii, available at: http://static.kremlin.ru/media/events/files/41d527556bec8deb3530.pdf, accessed on June 5, 2019), which uses the term dangers [opasnosti] (rather than the more serious term threats [ugrozi]) to describe the United States and NATO. On June 16, 2015, at the International Military-Technological Forum, Vladimir Putin stated, “This year, part of the nuclear forces will add more than 40 new intercontinental ballistic missiles that will be able to overcome any, even the most technically advanced, anti-missile defense system.” Here, it is important to note that these 40 missiles are new only in the sense that they represent newly manufactured lots of Yars, Bulava, and other missiles that are already part of the Strategic Nuclear Forces (SNF) inventory. This does not refer to the Sarmat missile, which has been redesigned as a new heavy-lift missile, or to the Rubezh missile package, the flight tests for which, as far as is known, are incomplete. In addition, as is well known to experts, other missiles in the SNF inventory—the Sineva, Voevoda, and Topol-M—possess effective means for overcoming anti-missile defenses that are incompatible, in terms of their quantitative makeup and quality, to those defenses the United States plans to deploy (The Kremlin, June 16, 2015, “Speech at the opening ceremony of the International Military-Technical Forum ‘Army-2015,’” available at http://kremlin.ru/events/president/transcripts/49712, accessed on July 22, 2016). For a widely held American view, see the testimony of the then Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Dunford, at his July 9, 2015, confirmation hearing that “my assessment today is that Russia presents the greatest threat to our national security.” (Committee on Armed Services, U.S. Senate, July 9, 2015, Hearing to Consider the Nomination of General Joseph F. Dunford, Jr., U.S. Marine Corps, to be Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, available at https://www.armed-services.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/15-62%20-%207-9-15.pdf, accessed on January 22, 2019; see also U.S. Department of Defense, 2018, Nuclear Posture Review, available at https://media.defense.gov/2018/Feb/02/2001872886/-1/-1/1/2018-NUCLEAR-POSTURE-REVIEW-FINAL-REPORT.PDF, accessed on January 22, 2019). The June 2015 National Military Strategy discusses Russia almost entirely in terms suggesting it is a threat, although without using that term specially (U.S. Department of Defense, 2015, The National Military Strategy of the United States of America, available at http://www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/Documents/Publications/2015_National_Military_Strategy.pdf, accessed on October 24, 2018).

† Unless otherwise noted, the calculations shown here were carried out by consultant to the joint committees, Jaganath Sankaran, under their supervision.

set aside the question of how accurately the systems can measure and predict the trajectory of the attack missile, intercept that trajectory in space and time (end-game guidance to hit the target), and effectively destroy the attacking missile if successful in hitting it. In other words, the joint committees make no estimate as to whether an interceptor theoretically capable of physically intercepting a missile would be able, in fact, to hit and destroy it.

The joint committees also made other technical assumptions in calculating the effectiveness of current U.S. regional and Russian Federation BMD systems. The primary assumptions are as follows:

- Missiles (intermediate-range ballistic missiles [IRBMs] and medium-range ballistic missile [MRBMs]) use minimum-energy trajectories.

- Missiles are independent (there is no interaction between and among missiles that change the effectiveness of the BMD systems, so additional missiles are treated as a simple superposition of missiles).

- No countermeasures are analyzed.

- For U.S. calculations, the joint committees assumed that interceptors are launched immediately after the end of boost phase. Although this is not realistic with today’s interceptor systems unless the end of boost is within view of particular radar systems, it shows the upper limits of defense capability because the end of boost phase is the earliest that an attack missile path can be predicted and an intercept point can be plotted.

EFFECTIVENESS OF U.S. REGIONAL BALLISTIC MISSILE DEFENSE SYSTEMS AGAINST INTERMEDIATE- AND MEDIUM-RANGE MISSILE THREATS

European Theater

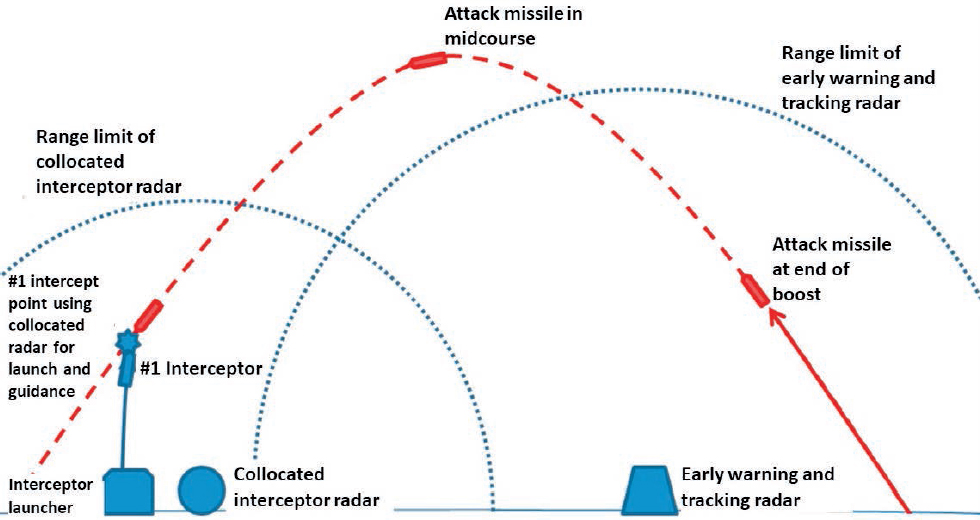

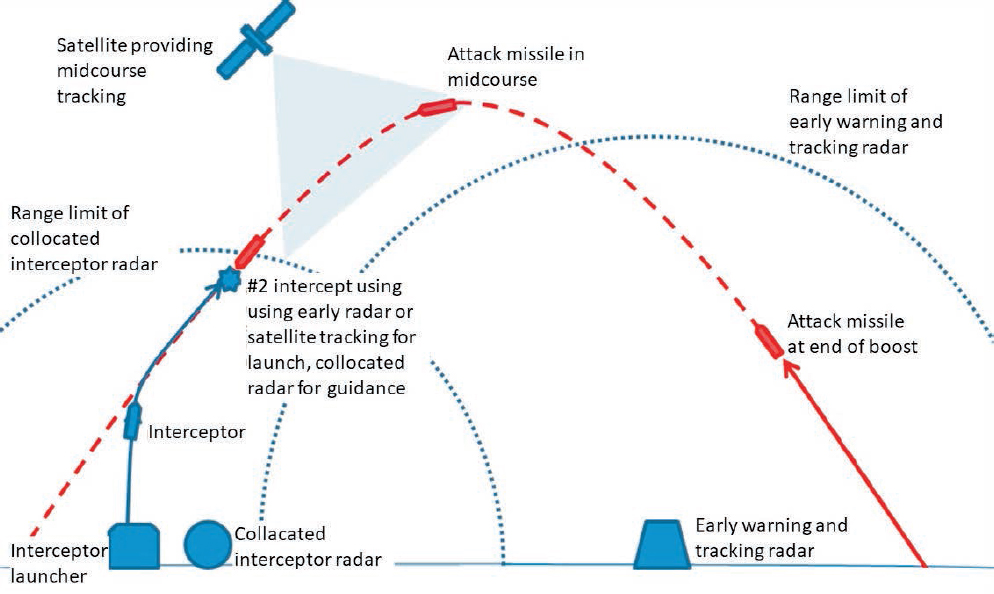

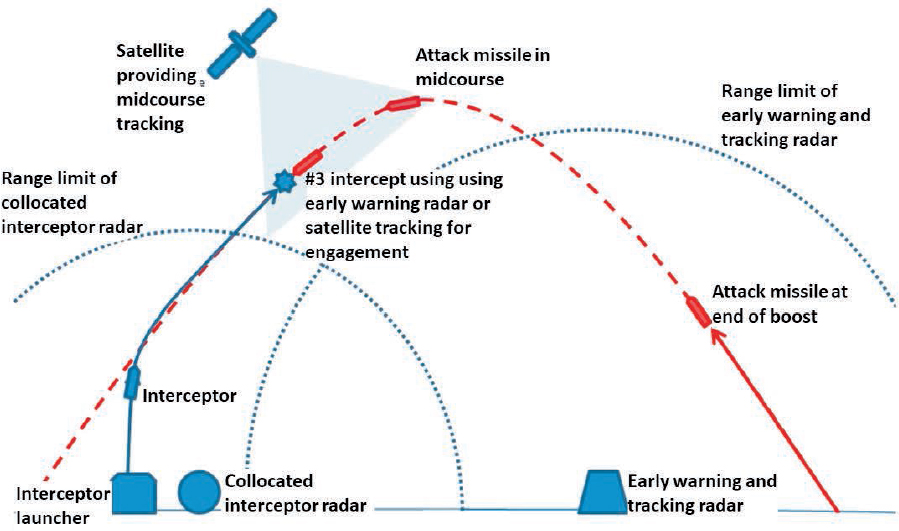

Figure 4-1 illustrates some of the elements of a regional ballistic missile defense system, including early warning and tracking radar installations, a satellite tracking system, and the collocated interceptor radar and launcher. The attack missile, shown in red, is launched, and at the end of its boost phase its path is determined by its momentum, gravity, and drag forces. The end of boost is the earliest that an intercept course or firing solution can be plotted by a radar or satellite system. The three intercept points on the figures represent different modes of operation. The leftmost intercept point, labeled #1 in Figure 4-1, could occur if the S-500 or Aegis Ashore system operates in regular operating mode: the interceptor is controlled for launch and engagement by the collocated radar at the intercept launch site. Intercept point labeled #2 in Figure 4-2, which could be achieved if the early warning and tracking radar system (or a satellite system) is integrated to provide the initial path for launch of the interceptor, and any in-flight guidance is provided by the radar system collocated with the interceptor launcher and the onboard infrared tracking system. In U.S. parlance, this is called “launch on remote,” or LOR. The intercept point labeled #3 in Figure 4-3 could be achieved if the early warning and tracking radar or a satellite system provide both launch and guidance to the interceptor, so that the intercept can occur outside of the range of the collocated radar. In U.S. parlance, this is called “engage on remote,” or EOR. If the early warning and tracking radar and satellite systems are not integrated into the interceptor launch and guidance systems (the first scenario in Figure 4-1), then the interceptor could be launched only after the attack missile has entered the collocated radar system’s range.

One important metric of the effectiveness of a regional BMD system is the area defended. Plots of defended area will be used throughout this chapter to illustrate the varying effectiveness of different BMD systems and their configurations. In each case, these defended areas reflect only the kinematic capability: requirements in space, time, and speed required for interception, not the probability of a successful intercept.

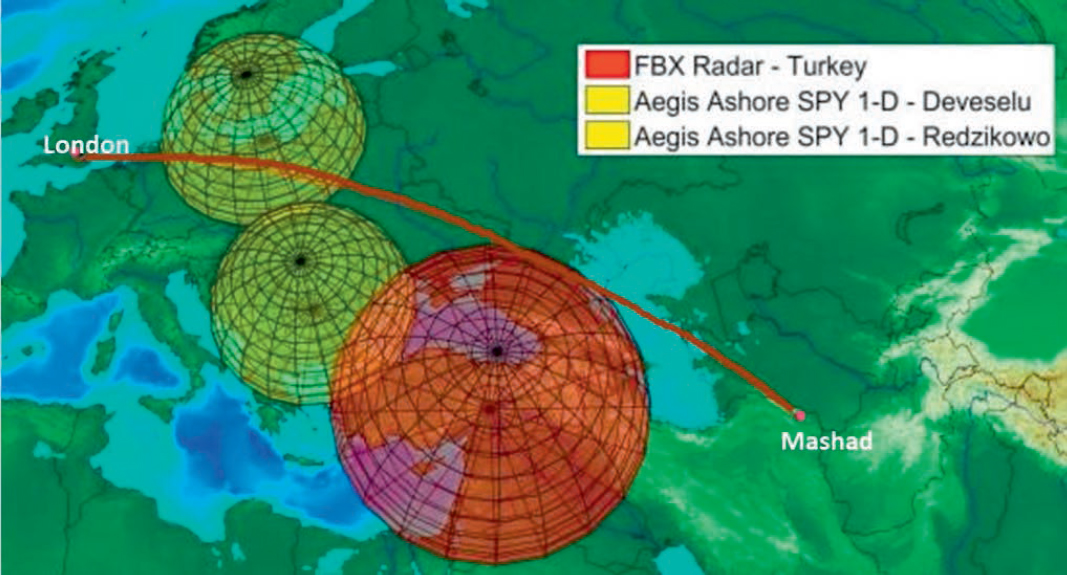

The joint committees considered the known missile threats from Pakistan, North Korea, and Iran, described in Chapter 3, and extrapolated to future missiles that could have the ability to strike Europe. To measure the effectiveness of the U.S. regional BMD system in Europe, its performance was calibrated against Iranian missiles. Three Iranian launch locations—Tabriz, Mashad, and Zahedan*—were chosen to nominally represent the azimuth spread of trajectory flight paths for Iranian missiles.† The planned U.S. regional BMD system in Europe consists of two sites, Deveselu in Romania and Redzikowo in Poland. The site in Deveselu was scheduled to host the SM-3 IB interceptor co-located with a SPY-1D radar (with an approximate tracking range of 650 km). The Deveselu site was declared operational in May 2016.70 The site in Redzikowo is planned to host both the SM-3 IB and SM-3 IIA interceptors.71 The Redzikowo site is planned to also host a SPY-1D radar. As part of the regional BMD system located in Europe, a forward-based X-band (FBX) radar with an approximate tracking range of 1,000 km is forward based at Kurecik, Turkey. While burnout velocities of SM-3 IB and IIA interceptors have not been officially released, it is reasonable to postulate that SM-3 IB interceptors would have a velocity of around 3.5 km/s and the SM-3 IIA interceptors would have a burnout velocity of around 4.5 km/s.72 These systems can

___________________

* Current Iranian ballistic missiles launched from inside Iran could reach only Bulgaria, Romania, and Turkey, all of which are NATO members.

† While Tabriz and Mashad are known missile launch/test sites, Zahedan is not. Zahedan is a city in Iranian Baluchistan. It was chosen to represent the most southeastern location in Iran from which a missile could theoretically be launched.

be supplemented with radar systems aboard Aegis ships deployed in the Mediterranean Sea and potentially with radar systems of other non-NATO member states.

Figure 4-4 shows the trajectory of a hypothetical Iranian IRBM launched from Mashad toward London. Also shown are the various radar systems deployed in Europe as part of the U.S. regional BMD. On this particular trajectory, the radar in Deveselu is not able to observe and track the missile. However, the radar systems at Kurecik, Turkey, and Redzikowo, Poland, are able to track the missile.

SOURCE: Created by J. Sankaran, consultant, 2016.

Out of a total of approximately 17 minutes’ flight duration, the FBX radar in Kurecik observes and tracks the missiles from Mashad, Iran, for a duration of around 2 minutes (from the 6th until the 8th minute), and the radar in Redzikowo observes and tracks the missile for a duration of around 2 minutes (from approximately the 13th until the 15th minute). The SPY-1D radar at Deveselu (which is assumed to have a tracking range of 650 km) is not able to observe this particular trajectory. However, if the missile were launched from another Iranian location, such as Tabriz or Zahedan, the radar at Deveselu might be able to observe and track a target missile.

Figure 4-5 shows the defended area using the U.S. regional BMD sites at Deveselu and Redzikowo against an Iranian missile launched out of Tabriz. The defended areas presented in Figure 4-5 assume a launch-on-remote operating mode. In an LOR mode, the predicted intercept point can be calculated using sensor data from a remote sensor system (one not co-located with the interceptor launcher). With this information, the interceptor missile can be launched before the radar system at the interceptor launching site/ship obtains a confirmed trajectory of the target missile. However, the final engagement and kill of the missile must wait until the actual target

missile trajectory is being tracked by the radars co-located at the interceptors launch site and on the Aegis ships. Technically, the intercept does not have to occur within the field of view of the tracking radar as the onboard infrared systems assist the guidance of the interceptor at the end of its trajectory. The effectiveness of LOR has been demonstrated for the U.S. Aegis BMD system in Europe.

While the U.S. regional BMD system operating in an LOR mode provides broad regional coverage of Europe, there are still noticeable coverage gaps. Note that these gaps would be greater (or in other words, the defended areas would be smaller) for what is called a “shoot-look-shoot” mode of operation, which requires a first interceptor (or set of interceptors) to be launched quickly enough that its success of interception can be assessed with sufficient time to launch a second interceptor (or set of interceptors) if the first one has failed.

The coverage gaps of the U.S. regional BMD system in Europe can be reduced if the system is able to operate in an engage-on-remote mode. In EOR mode, “the interceptor can be launched using any available target track, and engagement is controlled from in-flight target updates that can be provided to the interceptor missile from any Aegis AN/SPY-1 or AN/TPY-2 (FBX) radar.”73 In other words, in the EOR mode the interceptors at Deveselu could engage an Iranian missile even if the SPY-1D radar co-located at Deveselu is not observing and tracking that particular Iranian missile. Figure 4-6 shows the area defended when the European system operates in an EOR mode.

SOURCE: Created by J. Sankaran, consultant 2016.

SOURCE: Created by J. Sankaran, consultant, 2016.

When comparing Figure 4-6 with Figure 4-5, it is quickly apparent that an EOR mode provides substantial increases in coverage. In fact, nearly all of Europe could be defended by 4.5 km/s SM-3 IIA interceptors against the analyzed threat if EOR is possible. EOR was demonstrated for the first time in a December 2017 test.74 Operating in EOR mode would require earlier, more accurate radar data, which could be obtained through the placement of more forward-based radars or a more cooperative exchange of data with the Russian Federation. In such a cooperative mode, data from Russian radar systems can be used to inform the U.S. regional BMD system in Europe. Alternatively, a jointly developed satellite system that is able to provide highly accurate three-dimensional positioning and tracking could also enable EOR. The Russian Federation would also benefit significantly from such a satellite system, as is shown in Chapter 5.

Figure 4-6, above, shows the defended area of the U.S. regional BMD system operating in EOR mode in Europe against an Iranian missile launched from Tabriz. The defended areas, however, change depending on the launch site. Figure 4-7 shows the variation in defended area for launches from Mashad and Zahedan. The outer northwestern boundaries of the defended areas are defined by the range limits of the threat missiles, not the range limits of the interceptors.

SOURCE: Created by J. Sankaran, consultant, 2016.

These results above broadly agree with the calculations in the 2012 National Academies report Making Sense of Ballistic Missile Defense: An Assessment of Concepts and Systems for U.S. Boost-Phase Missile Defense in Comparison to Other Alternatives.75 Among many other issues, that study also examined the effect of interceptor velocity on the ability to kill an attack missile, assuming it was fired alone, and what effect that ability would have on the size of the area defended. However, in that study, Iranian threat missiles were presumed to be launched only from the central part of Iran. In addition, the 2012 study committee examined scenarios in which the threat missiles follow lofted or depressed trajectories,* resulting in different detailed results, but they are qualitatively similar to the minimum-energy-trajectory results obtained in this study. The 2012 study committee also examined the reduction in defended area if a shoot-look-shoot operating doctrine were employed.76

Asian Theater

Short-range ballistic missiles from North Korea pose threats to all of South Korea, including U.S. forces based there, because of their shared border and the two nations’ relatively

___________________

* A missile launched at a depressed trajectory is launched at a smaller angle from the Earth’s surface and travels closer to the surface than a normal trajectory, while a missile launched at a lofted trajectory is launched at a larger angle and arcs high above the Earth’s surface.

small geographic areas. However, defense against short-range missiles is outside of the scope of this study.

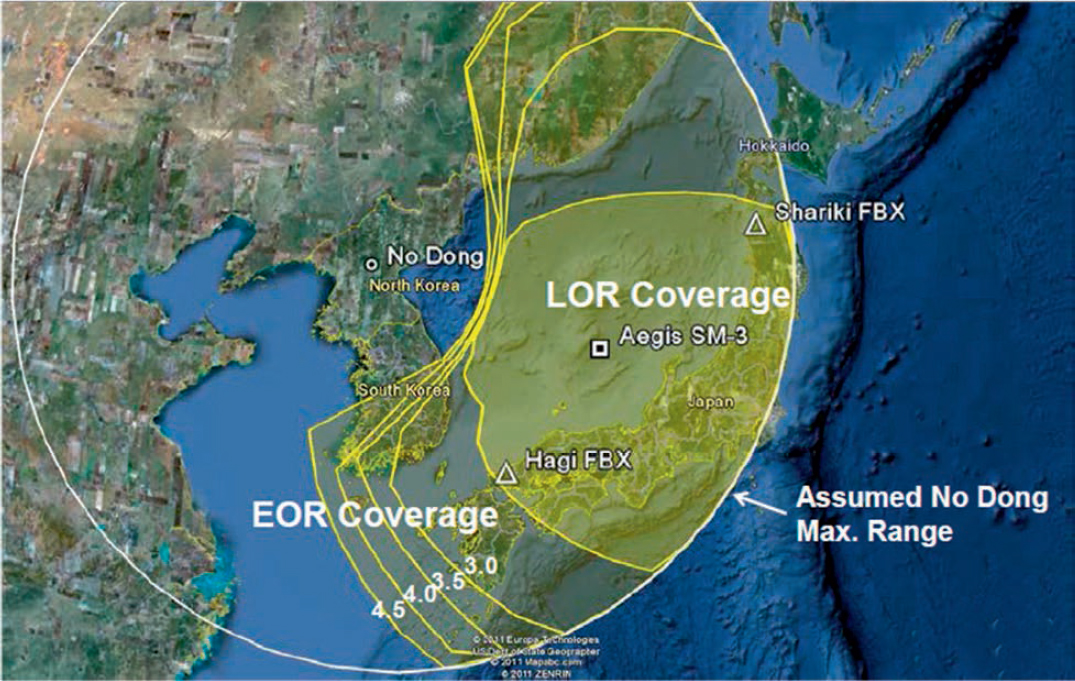

IRBMs from North Korea threaten Japan and U.S. forces based in Japan. Target sites in Japan would be at the low end of the known or assumed missile ranges of North Korean missiles; these missiles would have relatively short burn times and low altitudes. Figure 4-8 shows the area that Aegis ships with shipboard interceptors located in the Sea of Japan are kinematically capable of defending against such missiles, according to the 2012 National Academies study.77 The figure shows the results of calculations with various interceptor burnout velocities, ranging from 3.0 to 4.5 km/s, defending against a North Korean No Dong Mod 1/2 missile (1,200-1,500 km) range. Figure 4-8 shows both EOR and LOR coverage, and assumes an FBX radar facility in Hagi, Japan. The difference in coverage between LOR and EOR are apparent in the figure. Note that using an LOR doctrine requires that the threat missile be in the range of the ship-based radar during the interception.

At the maximum end of North Korean IRBM range, the United States must consider defense of the island of Guam, which is a U.S. territory. However, because the island is far from the launch location, should such a missile be launched, the United States would presumably utilize

SOURCE: NRC, 2012, 97.

terminal defense* in the form of Aegis ships stationed near the island and a Terminal High Altitude Air Defense battery on the island.†

EFFECTIVENESS OF RUSSIAN BALLISTIC MISSILE DEFENSE SYSTEMS AGAINST INTERMEDIATE- AND MEDIUM-RANGE MISSILES

The objective of the Russian BMD system is not to defend the entire territory of the Russian Federation. According to the official assessment of Russian government experts, and based on the number of interceptors that the Russian Federation is expected to possess by 2020, the system will be capable of defending up to 15 military-industrial centers, each covering an area of about 10,000 km2, against an attack of between one to five warheads.78

According to the approved plan of the Russian Federation, defending one military-industrial center from five incoming missiles with 95 percent probability of success is assessed to require 14 interceptor missiles. This is based on the estimate that the interception of one attack missile (warhead) with 95 percent probability of success requires 4 interceptors (recall that one interceptor package consists of 8 launchers, each having 4 interceptors, and that the predicted total of 480 interceptors will be deployed across the territory of the Russian Federation by 2020).‡ The ratio of interceptors to attack missiles changes nonlinearly for the same probability of success as the number of attack missiles increases because of the potential for interactive effects.

The Russian approach to missile defense differs significantly from that of U.S. regional missile defense. The Russian Federation can only protect specified military-industrial territories of a particular type and size.

To further evaluate the effectiveness of the Russian BMD system, the joint committees assessed its performance against Pakistani missiles. Unlike the Iranian case, only one launch location—Peshawar—was chosen. Given the narrow geographical territory of Pakistan with respect to trajectories aimed at targets in the Russian Federation, different launch locations did not significantly alter the defended area.

By 2020, Russia plans to field a number of components of its BMD system—the S-300 PMU (“Favorit”), S-350 (“Vitiaz”), S-400 (“Triumf”), and S-500 (“Prometei”) air defense missile systems, as well as the upgraded A-135/235 anti-missile defense system. In order to model these various BMD systems, the burnout velocity of the interceptor missiles used to determine the defended area was parametrically varied from 3.5 km/s to 5.0 km/s. Similar to the U.S. regional BMD systems, LOR and EOR performances were calculated separately for the Russian BMD systems.

While Russian early warning radars would be able to detect a launch from Pakistan quickly and cue the tracking radar, interceptor launch would most likely occur only after the missile tracking radar co-located with the interceptor detected the missile. The Russian S-500 BMD systems also could in principle operate in an LOR mode. In order to estimate a defended area under LOR mode, a tracking radar range of 400 km is assumed in these calculations. While the actual

___________________

* Terminal defense intercept is defined as interception occurring after the vehicle reenters Earth’s atmosphere. See: NRC, 2012, p. 3.

† Aegis ships provide mobile BMD, but also other important missions, including air defense, anti-submarine warfare, and naval gunfire for amphibious forces. Aegis ships are not normally assigned to protect a ground facility.

‡ If there were 15 military-industrial centers (MIC) in the Russian Federation, each with 32 interceptors, there would be 480 interceptors. In other words, if one package were deployed to each MIC, each package would contain 8 launchers each capable of holding 4 interceptors for a total of 32 interceptors per MIC.

radar range may vary depending on the particular BMD system, an approximate range of 400 km for MRBMs and IRBMs is reasonable for the S-400 91N6E radar.

Figure 4-9 shows the areas defended by Russian BMD systems against a missile hypothetically launched from Peshawar, Pakistan, using an LOR operating mode. The Russian BMD systems are assumed to be deployed at three locations: Moscow, Omsk, and Samara. These three locations were chosen for the joint committees’ calculations because they are large military-industrial areas containing major Russian cities. The northwest boundary of the defended area near Moscow is limited by the range of the threat missile, not the BMD system. Chapter 5 (in particular, Figures 5-1, 5-2, and 5-3) shows how the performance of these systems improve with EOR.

SOURCE: Created by J. Sankaran, consultant, 2016.

LIMITATION OF EXISTING AND NEAR-TERM CAPABILITIES

Currently, the Russian Federation and the United States are deploying ballistic missile defenses that are at least kinematically capable of intercepting attack missiles from the countries identified in this report without any cooperation between them. Indeed, neither would be willing to depend exclusively on the other for the effectiveness of an important military capability. The coverage maps presented in this chapter illustrate the potential to defend large areas against IRBMs. These maps, however, assume capabilities that are still in development. Even when ongoing improvements are deployed and operational, they will only be effective if attack missile launch is detected and accurate tracking data are available from attack missile burnout until interception. Furthermore, the better and more timely the tracking data the greater the effectiveness

of each interceptor against the attack missiles. This means that earlier and better tracking data can reduce the number of interceptors needed for a given missile kill probability; therefore, one can lower the cost of achieving a given level of confidence in defense, or one can achieve a higher confidence in defense for the same cost.

As third-country capabilities improve, tracking and discrimination of attacking missiles will become increasingly important. Both states may require improved capability to keep pace with the increasing threat. Enhancing U.S. and Russian ability to detect, track, and discriminate against attack missiles is, in the joint committees’ judgment, an area where a cooperative approach may provide significant benefits to both countries. Options for cooperation and the associated benefits are described in the next chapter.

This page intentionally left blank.