2

Potential Challenges and Opportunities in Rural Communities

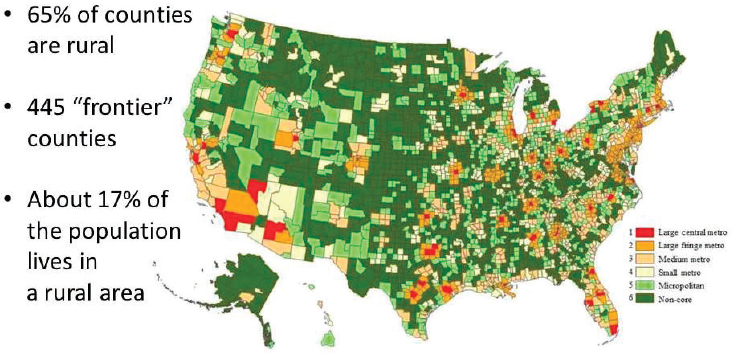

Rural America is not a smaller version of urban America, observed Tom Morris, associate administrator in the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy in the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), in the first of two keynote presentations at the workshop (see Figure 2-1). On average, rural areas have higher levels of poverty, higher percentages of older adults, and slower growing or declining populations. Morris explained that the payer mix for health care tends to be different than what is found in urban areas. In rural communities, Medicare, Medicaid, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program are the dominant payers. In

SOURCES: As presented by Tom Morris, June 13, 2017; Ingram and Franco, 2012.

urban areas, third-party insurance tends to be the dominant payer. As a result, changes to Medicare and Medicaid have a disproportionate effect on rural providers and their ability to provide care to the citizens in their communities.

Although there are commonalities among rural areas, they can also differ greatly from each other. Rural areas in the deep South face different issues than rural areas in Maine, Morris pointed out. In the western United States, weather can be a limiting factor in a way that it is not in other parts of the country. The mix of health care providers varies, although many areas suffer from provider shortages.

Multiple definitions of the term rural exist. The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) uses a system based on counties. The Census Bureau uses a system based on census tracts. In his presentation, Morris used OMB’s definition, which identifies about 17 percent of the population as living in rural areas spread across about 80 percent of the country’s land mass (see Figure 2-1). About two-thirds of the nation’s approximately 3,100 counties and county equivalents are rural, including about 450 geographically remote and isolated “frontier” counties.

Nonmetropolitan areas have fewer physicians than metropolitan areas—5.5 versus 7.9 per 10,000 people (Larson et al., 2016). When nurse practitioners and physician assistants are included, the disparities remain—11.6 versus 16.2 per 10,000 people. The same applies to dentists—3.6 versus 5.9 per 10,000 people—and to dental hygienists—4.5 versus 5.0 per 10,000 people.

Even more striking, said Morris, is the relative lack of mental health providers in rural communities. About 200 counties—17 percent of the nonmetropolitan counties—have no mental health practitioner at all: “No psychologists, no psychiatrists, no licensed clinical social workers, no psychiatric nurse practitioners,” he explained. This is a “real challenge,” said Morris, for addressing behavioral health.

Given the economic challenge of providing care in rural communities, federal legislation provides special protections to the hospital and clinical infrastructure in these areas. Of the approximately 2,000 rural hospitals in the United States (out of a total of 5,000 to 6,000 hospitals, depending on definitions), approximately 1,300 are “critical access hospitals,” meaning that they have 25 beds or fewer and, in most cases, are more than 35 miles from another hospital. These hospitals get special protection from Medicare and an eased regulatory burden. Without these protections, said Morris, the United States would potentially have “a real problem in terms of ensuring access to inpatient and emergency care in rural communities.”

Over the past 15 years, the system of federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) in the United States has grown substantially, with a particular emphasis on oral health and mental health. About 10,000 FQHC service sites are scattered across the United States, with about 40 percent of these either located in or serving rural communities. In addition, about 4,000 Medicare-certified rural health clinics exist in the United States. About half of these are provider based, meaning that they are owned by small, rural hospitals.

From 1999 to about 2010, the critical access hospital designation had stabilized rural hospitals’ economic challenges, according to Morris. However, since 2010, about 79 rural hospitals have closed their doors or suspended operations (although, as of the middle of 2017, only two had closed in that year).1 Several factors account for these closures, including declining populations, declining in-patient use, and changes in the payer mix, said Morris. “It is tough to keep a full-service hospital open in some communities where you just don’t have enough population base,” said Morris. In other cases, “market factors [are] at work that made it impossible for those facilities to continue.” (The section titled “The Closure of Rural Hospitals” in Chapter 5 discusses this issue in more detail.)

In rural areas, emergency medical services (EMS) are largely volunteer driven and have to cover vast geographic areas with a low patient volume. “Providing EMS can be a real challenge,” said Morris. In addition, rural public health departments derive less of their revenue from local communities and are more reliant on billing for services than their urban counterparts.

___________________

1 As of the workshop date, there were 70; this is a continuously fluctuating number.

The differences between rural and urban areas create several pitfalls for federal health care policy, Morris observed. Payment systems are based on the average cost of cases, but in rural areas a high-cost case paired with a fixed-cost payment can create economic difficulties. Solutions to problems that work in urban areas may not work in rural areas. For example, when Medicare started paying for diabetes self-education management, many rural communities could not meet the requirements for trained personnel needed for reimbursement. While this situation “has gotten better over the years,” said Morris, “I offer it more as a metaphor for some of the challenges when we think about this.” Even the very successful Nurse–Family Partnership program has requirements that are not necessarily attainable for smaller communities in terms of the credentials of the care team required to implement the model, he commented.

As discussions about the prospect of federal funding move toward block grants, states may focus on the areas with highest needs, in part to meet performance metrics, while overlooking low-population areas, Morris continued. Other kinds of grants also may focus on areas that contain larger numbers of people, and evaluations may pass over rural areas because the population base is not large enough for statistically significant results. “I am all for academic rigor, but there are ways to think differently about evaluation so as not to let it be at the detriment of a high-need population,” he said.

Technological approaches, such as telehealth, are often held out as solutions for rural health care. But technology is a tool, not a solution, said Morris. There are still challenges in fully integrating telehealth into the day-to-day delivery of care. Similarly, electronic health records (EHRs) provide the potential for clinical information to follow the rural patients who get care in urban settings, but these systems continue to have gaps owing to challenges with interoperability and health information exchange. In addition, some parts of the country still do not have access to robust or affordable broadband service, which limits the flow of information.

FEDERAL ACTIONS

The federal government invests in rural health through a number of mechanisms, Morris observed, including the following:

- Workforce training

- Clinician placement, including through the National Health Service Corps

- Infrastructure support

- Targeting resources by designating shortage areas

- Enhanced payments through Medicare and Medicaid

- Pilots and demonstrations

- Provision and support of public coverage

- Investments in technology, including telehealth, broadband, and EHRs

A range of federal agencies support these efforts, such as when the U.S. Department of Agriculture helps rebuild or renovate a hospital or a community health center, or the Federal Communications Commission supports broad communications infrastructure [that also meets health sector needs]. The federal government also significantly improves health care delivery in rural areas through Medicare, Medicaid, and other forms of allocation and direct funding.

The Office of Rural Health Policy under HRSA was created about 30 years ago to be the voice of rural health in HHS. It reviews how federal policies and programs affect rural communities and seeks to put research findings into the hands of leaders in both rural and urban areas at the state and federal levels. It funds seven rural health research centers around the country and a national clearinghouse for rural health information at the University of North Dakota. It is “trying to develop a rural evidence base so that people can replicate what we know works in rural communities,” said Morris.

The office invests about $60 million per year in community-based funding that is limited to rural communities so they do not have to compete with metropolitan areas. Its programs include public health screening, care coordination, defibrillator and opioid-reversal programs, grants focused on performance and quality improvement for small rural hospitals, state offices of rural health, telehealth network grants and resource centers, and licensure and portability efforts. As an example, Morris cited a brief prepared by the National Advisory Committee on Rural Health and Human Services (2017) on the social determinants of health in a rural context. One of the committee’s key findings was that funding mechanisms can make it difficult for rural communities to bring resources to bear on health disparities, and the committee offered several recommendations to overcome these difficulties.

Morris explained that in fiscal year 2016, 160,000 parents and children nationwide received HRSA-supported home visiting services. These services took place in 35 percent of all urban counties and 23 percent of all rural counties. Training grants support more than 187,000 students from rural areas, and HRSA-supported training spots include about 8,400 rural locations.

Other parts of HHS are relevant to rural health, including the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Administration for Children and Families, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the

National Institutes of Health, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Indian Health Service, and the Administration for Community Living. For example, the Health Rural Council within CMS has helped that part of HHS understand the challenges of rural communities. CMS has also supported Innovation Center awards, technical assistance targeted to rural and underserved areas, and the Connected Care Management Campaign, which is focused on patients with one or more chronic health conditions, including patients in rural and underserved areas. CDC has run a series of articles on rural health in its Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. “It is great that CDC is now looking at rural health. That is the kind of thing that needs to happen,” said Morris. “They are, in my mind, the key public health agency in HHS, and when they focus on rural health issues, it garners national attention,” he said.

At an interagency level, the Federal Interagency Health Equity Team has considered rural issues. The National Advisory Committee on Rural Health and Human Services focuses on both rural health and rural human service issues, issues policy briefs, and makes recommendations to the HHS secretary. In addition, federal agencies invest in non–health care services that have an effect on health, Morris pointed out in response to a question. For example, the Center for Innovation at CMS has supported the Accountable Health Communities Model, which focuses on services such as housing that affect health outcomes.

OVERLAPPING INEQUITIES

Inequities based on race and ethnicity overlap with and intensify inequities based on geography, observed Michael Meit, co-director of the NORC Walsh Center for Rural Health Analysis and senior fellow in NORC at The University of Chicago Public Health Research Department, in the second keynote address of the workshop. “When you overlay those two, you have a dual disparity. That is where you will find many of the greatest disparities we have in our country,” he said.

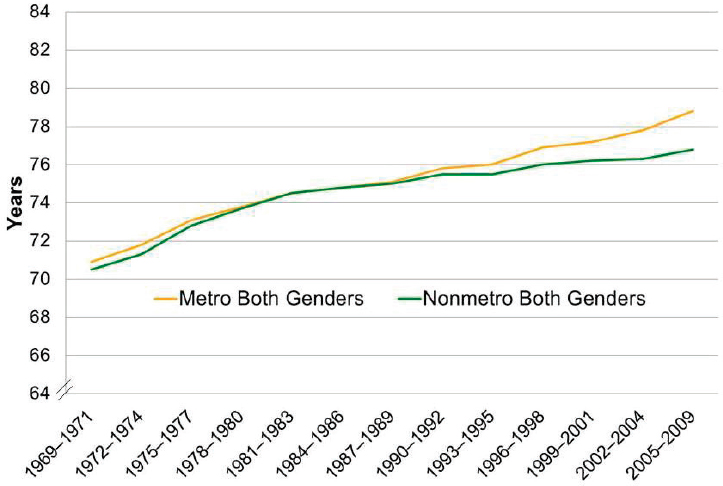

Meit explained that on average, life expectancies in rural areas are lower than those in urban areas, and the gap has been widening since the two rates were equal in the early 1980s (see Figure 2-2). Other recent data (not shown in Figure 2-2) reveal that for the U.S. population as a whole, life expectancy has recently declined for the first time since the AIDS epidemic of the early 1990s. The current decline in life expectancy is tied to three “diseases of despair,” said Meit: overdose (including opioids), alcoholic liver disease, and suicide. These conditions are disproportionately affecting rural populations, Meit added, further widening the gap between urban and rural.

SOURCES: As presented by Michael Meit, June 13, 2017; adapted from Singh and Siahpush, 2014.

More broadly, social factors have a major effect on health, Meit observed. The Healthy People 2020 Framework divided the social determinants of health into five categories:

- Economic stability—poverty, employment, food security, housing stability

- Education—high school graduation, enrollment in higher education, language and literacy, early childhood education and development

- Social and community context—social cohesion, civic participation, perceptions of discrimination and equity, incarceration/institutionalization

- Health and health care—access to health care, access to primary care, health literacy

- Neighborhood and built environment—access to healthy foods, quality of housing, crime and violence, environmental conditions

Across most of these social determinants of health, rural populations do not fare as well as urban populations. The median household income

in rural areas is $10,000 less per year on average than in urban areas, said Meit. About 5 percent more children live in poverty in rural counties (26 percent) than in urban counties (21 percent). In rural counties, 16.5 percent of adults have less than a high school education (compared with 14.7 percent in urban counties), 36.3 percent have only a high school diploma (compared with 31.9 percent in urban counties), and 17.4 percent have a bachelor’s degree or higher (compared with 24 percent in urban counties), Meit explained.

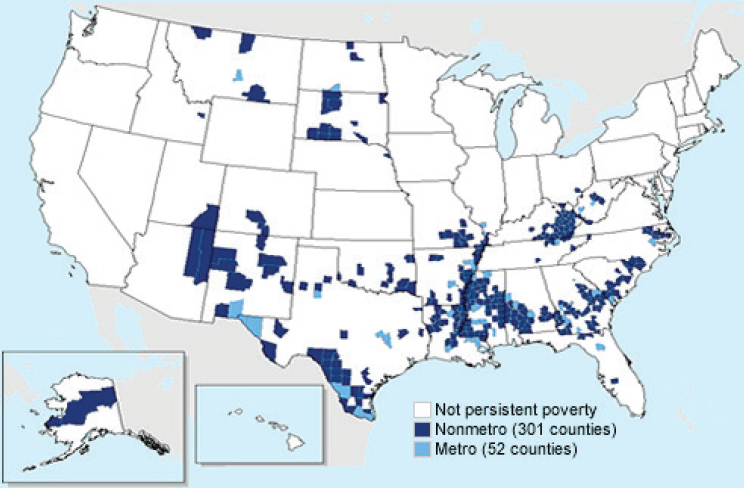

In his presentation, Meit focused on the approximately 350 counties in the United States designated as “persistent poverty counties,” where the county has had a greater than 20 percent rate of poverty since the 1980 census (see Figure 2-3). “Don’t think that this is the only place where poverty lives, but this is where poverty is persistent,” noted Meit. The counties are largely rural, including counties in Appalachia, the Mississippi Delta, the “Stroke Belt” in the southeastern United States, and along the U.S.–Mexico border.

These regions are also the areas with the highest rural minority populations, with African Americans in the South and Southeast, Hispanics

SOURCES: As presented by Michael Meit, June 13, 2017; USDA, 2017.

along the border, and Native Americans in New Mexico, Arizona, and the Plains states. In addition, these counties are often designated as Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs). The connecting link, said Meit, is poverty, which “is probably the greatest predictor of health status that we have.”

A study done through the Rural Health Reform Policy Research Center, a collaborative effort of the NORC Walsh Center for Rural Health and the University of North Dakota Center for Rural Health, examined the effect of rurality on mortality and regional differences in the primary and underlying causes of death. The study examined mortality data for the 10 leading causes of death by age bracket (for the 25 to 64 years age range, this included cerebrovascular diseases, diabetes, heart disease, homicide, liver diseases, lower respiratory diseases, malignant neoplasms, septicemia, suicide, and unintentional injuries). Data were analyzed for each of the 10 regions into which HHS divides the country (with the addition of the Appalachian and Delta regions separately), and the National Center for Health Statistics’ urban–rural classification scheme for counties (which distinguishes large central, large fringe, small/medium metropolitan, micropolitan, and noncore) was applied to the analyses along with age and gender (although not race or ethnicity).

In region 4, which covers the southeastern United States and includes a high percentage of African Americans, men ages 25 to 64 living in rural counties generally fare far worse on measures of the 10 leading causes of death than those living in urban counties, with the exception of homicides, said Meit. Rural women living in rural counties fare worse on all 10 leading causes of death. Rural men in this region are more than twice as likely to die from lower respiratory disease as other men in the United States, and 60 percent more likely to die from unintentional injury. Rural women in this region are more than 2.2 times as likely to die from lower respiratory disease, twice as likely to die from unintentional injury, and 60 percent more likely to die from diabetes.

In region 6, which covers Arkansas, Louisiana, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas, and has a high percentage of Hispanics, a similar pattern appears, with lower respiratory diseases and unintentional injuries especially prominent among rural men and women. Similar conclusions can be drawn about regions that have large numbers of Native Americans. Rural health indicators are especially poor where rural areas intersect with large minority populations, Meit said.

Every part of the country “has a story to tell,” said Meit. It may be a story about slavery, about the creation of Indian reservations, or about cross-border relations, but these stories reflect both historical processes and current health status. “You cannot separate [disparities] from culture

and history. That is something we need to delve into much more deeply,” he explained.

Meit also focused on the Appalachian region, a region that faces considerable health disparities despite not having large minority populations. Meit discussed what have been referred to as the “diseases of despair,” which include deaths resulting from overdose, suicide, and alcoholic liver disease. In the Appalachian region, mortality rates for liver disease, suicide, and unintentional injuries (which include overdose deaths) are all above the national average for men ages 25 to 64. Rates for rural women are also above the national average for suicide and unintentional injuries.

Recent work conducted by the NORC Walsh Center for Rural Health Analysis, on behalf of the Appalachian Regional Commission, has shown that the combined age-adjusted mortality rate for diseases of despair in Appalachia is 66.6 per 100,000 people, compared with 48.6 per 100,000 people in the United States as a whole—including a 7 percent higher rate of mortality resulting from alcoholic liver disease, a 17 percent higher rate of mortality resulting from suicide, and a 40 percent higher rate of mortality resulting from overdose deaths (69 percent of which is attributable to opioid overdose). Future analyses will explore patterns within Appalachia by age, subregion, and county economic indicators, said Meit.

Meit ended by talking about some of the resources available to strengthen rural health programs. The NORC Walsh Center is developing a series of evidence-based toolkits based on what works in rural communities. Most programs are not tested in rural communities, and these communities may need unique models, said Meit. The toolkits capture programs that work in rural areas and help communities replicate those models, with new toolkits being created on a continuing basis. Toolkits are housed in the Community Health Gateway, part of the Rural Health Information Hub, which Meit referred to as “a one-stop shop for everything rural.”

Meit also highlighted new work being conducted by the NORC Walsh Center that is funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. This body of work seeks to identify strengths and opportunities that can accelerate and improve health and well-being in rural communities; identify factors (and partners) that can influence health and well-being within rural communities, such as transportation, faith, education, and business; and identify opportunities for action and a set of recommendations for diverse rural stakeholders and funders. Through this project, the NORC Walsh Center has worked to identify assets that can be leveraged in rural communities, including individual, organizational, community, and cultural assets (Kretzmann and McKnight, 1993). Meit noted that the cultural assets are an important component of this framework in rural communities, describing them as “the greatest assets that we have.” He concluded:

People are proud of their heritage. They are proud of their communities. . . . Rural communities are close-knit. People know each other. They come to each other’s aid. They are resilient. There are a lot of really positive factors about being in a rural community that can be leveraged.

DISCUSSION

In a wide-ranging discussion session, Morris and Meit touched on a number of issues, including scope of practice, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), public health programs in rural areas, and the politics of health care.

In response to a question about state policies on scope of practice for advanced practice nurses, Morris pointed out that primary care providers “should be able to practice to the extent of their training.” But these issues are inevitably political, he said, adding that “the best thing we can do is bring attention to it.” For example, the National Conference of State Legislatures published on its website a state-by-state comparison of scope of practice for various health care professionals.

Both speakers also commented on the ACA, for which Congress was considering a replacement at the time of the workshop. Meit pointed out that many people gained insurance under the act, but they did not necessarily gain access. Demand for health care increased, but the demand was often directed toward health departments that already had provider shortages.

Morris took a longer-term view by citing the history of Medicare Part D, which increased access to medicines. As the program evolved, it garnered broad bipartisan support. He also pointed out, however, that insurance regulation tends to work against rural communities. Risk needs to be pooled among larger populations, he said, to attract insurers, “and not just for the Affordable Care marketplaces but for every form of insurance.”

In response to a question about the training of EMS personnel, Morris observed that they are volunteers, which raises questions about the requirements they can be asked to meet. Yet, even a little training in behavioral health care “would go a long way,” he said. One positive model is the concept of community paramedicine (i.e., paramedics and emergency medical technicians operate in expanded roles),2 in which rural communities ask how they can deploy the resources they have in a more efficient and effective manner. If a reimbursement system can be

___________________

2 From Rural Health Information Hub: https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/community-paramedicine (accessed November 20, 2017).

worked out, such a model could accommodate wellness checks, home visits, and other services.

Meit reemphasized the need for federal dollars to make it to rural areas in an equitable way. States tend to focus on larger population centers to produce results that justify the expenses. “That also means, as a byproduct, that dollars aren’t making it to rural communities, which are facing very significant disparities,” he said, adding that a possible policy proposal would be to call for ensuring that the same percentage of federal funding for such purposes be allocated to rural communities as the percentage of a state’s population in rural areas.

Workshop participant Dale Quinney, executive director of the Alabama Rural Health Association, pointed to several problems with definitions of “rural” areas. The diagram of chronic poverty counties in Alabama included Pickens, Hale, and Lowndes counties as urban, but “there ain’t no way that those are urban,” he said. The Census Bureau asks states for input on the categorization of census tracts, but that does not happen with counties. Similarly, the methodology for specifying HPSAs is flawed, he said. Yet, HPSAs are associated with physician incentives that can skew decisions about whether or not to provide care in a particular place. “We had a county not long ago that was about to lose its HPSA status because it employed one physician too many,” said Quinney. “Physicians threatened to leave and go elsewhere because they were going to lose that bonus payment each year.” Incentives should work to reward rather than punish the provision of more care, he argued.

In response to a question about the role of public health in rural areas, Meit observed that every state has a unique public health infrastructure. Some state health departments include their Medicaid agencies. Others include environmental programs. Some state health departments are centralized while others are decentralized. This makes it difficult to quantify the public health infrastructure in states and even harder to compare funding among states, he said.

Overall, however, the public health infrastructure “struggles more in our rural communities,” Meit continued, adding “We have good data to demonstrate that.” Furthermore, funding seems to be getting even tighter for small rural health departments. Meit asked:

What is the implication of not having boots on the ground in our communities to do disease surveillance, to track infectious disease, to do epidemiological investigations to control outbreaks, to do health education, all of the core work of public health?

Public health organizations and associations have tended to overlook rural issues, and the National Rural Health Association has not done a great job of talking about public health, said Meit, adding:

They have tried over the years, but their membership is largely hospitals and clinics, so they talk about access. The public health organizations tend to have more urban membership, so they don’t talk about rural. We need to bring this all together and talk about rural population health. That is the path forward.

Morris added that the federal agencies working on human service rural infrastructure, such as the Administration for Children and Families and the Administration for Community Living, are even more stretched than the health agencies. Yet jobs, economic sustainability, and families are critical factors in health issues.

In a discussion about the dissemination and scaling up of successful models, Morris pointed out that it is often easier to ramp up a model that has proven successful in a rural area than to translate an evidence-based model from an urban area to a rural one, given the frequent need to discard parts of the model for use in a rural area. Rural communities can be better places to test models than urban communities because fewer things are going on that can potentially influence outcomes.

Rural communities also have more room for improvement, said Morris, and a lack of resources can lead to more innovation in rural communities than urban ones. He explained:

When you don’t have a lot of dollars coming in, you have to be creative in thinking about how you get things done. If we can capture that and figure out what is it that can be distilled and exported to other rural communities, but also potentially scaled up to influence urban outcomes, there is a lot of opportunity.

The challenge is finding promising innovations. He said that less money is needed to make a difference in a rural community, adding “When I watch some of my federal partners, they think in terms of millions. I think in terms of thousands.”

Turning to political considerations, Meit described the need to do a better job of communicating to rural residents the benefits provided by federal programs. “When the issues are framed properly, they support the activities that are being provided,” he said. For example, with public–private partnerships, the private side of the partnership can resonate more strongly in rural communities, and he explained that “if our residents support us, they will communicate to policy makers.”

Morris added that rural health and inequities between rural and urban areas have traditionally been bipartisan issues. Starting with the data opens the door to talking about the challenges that exist today, regardless of political party. Also, states, foundations, and other entities beyond the federal government have invested in rural health. “We can do a better job of connecting people to resources,” he said.

Finally, both keynote speakers referred to the importance of transpor-

tation in shaping rural health care. “In every rural meeting we have held, the two issues that come out at the top in terms of infrastructure capacities are transportation and broadband,” said Meit. Morris agreed about the importance of transportation, adding “Sometimes we make it harder than it needs to be.” A Head Start van may not be able to transport anybody else because of liability issues. School buses can only transport students, and senior services transportation can only take seniors. “We can get more creative if we would just untie ourselves,” he concluded.