1

Introduction

The Social Security Administration (SSA) administers two programs that provide disability benefits: the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) program and the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program. SSDI provides disability benefits to people (under the full retirement age) who are no longer able to work because of a disabling medical condition (or who have a terminal illness). SSI provides income assistance for disabled, blind, and aged people who have limited income and resources regardless of their prior participation in the labor force (SSA, 2017a). Both programs share a common definition of disability for adults, i.e., “the inability to engage in any substantial gainful activity by reason of any medically determinable physical or mental impairment which can be expected to result in death or which has lasted or can be expected to last for a continuous period of not less than 12 months,” as well as a common disability determination process administered by SSA (SSA, 2017a). Disabled workers might receive either SSDI benefits or SSI payments, or both, depending on their recent work history and current income and assets. Disabled workers might also receive benefits from other public programs such as workers’ compensation, which insures against work-related illness or injuries occurring on the job, but those other programs have their own definitions and eligibility criteria.1

In the present report, the Committee on Health Care Utilization and Adults with Disabilities (hereafter referred to as “the committee”) discusses SSDI and SSI as they both employ the Listing of Impairments2 (also referred to as “the Listings”) in their determination processes.3 This chapter introduces the two programs and discusses the disability-determination process. The remainder of the chapter presents the committee’s task, its approach to the task, and the organization of the report.

THE SOCIAL SECURITY DISABILITY INSURANCE PROGRAM

The SSDI program was authorized by Title II of the Social Security Act and enacted in 1956 to provide benefits to disabled workers who have paid into the Social Security system and

___________________

1 There is no federal role in state workers’ compensation. State compensation programs vary widely with regard to coverage, benefits, and administrative practices (Social Security Bulletin, Volume 65, No. 4, 2005).

2 See https://www.ssa.gov/disability/professionals/bluebook/AdultListings.htm, accessed February 1, 2018 (SSA, 2017b).

3 See 20 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Part 404, Subpart P, Appendix 1.

who are younger than the Social Security full retirement age. The goal of SSDI is to replace a portion of a worker’s income in the event of illness or disability in amounts related to the worker’s former earnings. The SSDI program also provides Medicare coverage after a 2-year waiting period. SSDI is financed by the Social Security payroll tax, so any person who qualifies as disabled, according to the SSA definition of disability (inability to engage in any substantial gainful activity) and has paid Social Security taxes long enough to achieve sufficient work credits can receive SSDI.

In December 2016, almost 9 million people received disabled-worker benefits under the SSDI program. Some 1.8 million children and 148,955 spouses of disabled workers also received benefits. The average monthly benefit to disabled workers was $1,171, which is equivalent to $14,052 a year.4 As noted, SSDI benefits are financed primarily through Social Security payroll-tax contributions, which totaled about $143 billion in 2016 (O’Leary et al., 2015; CBPP, 2017).

In December 2013, 48 percent of disabled-worker beneficiaries were women (SSA, 2013). According to the SSA 2010 National Beneficiary Survey (SSA, 2010), 70 percent of disabled workers are white, 23 percent are black, and 8 percent identify themselves as belonging to another racial group or to multiple groups; 12 percent of disabled workers identify themselves as Hispanic. Nearly 1 million veterans of the armed forces receive SSDI benefits.

About one-third of disabled-worker beneficiaries have musculoskeletal conditions (such as severe arthritis or back injuries) as a primary diagnosis. Another one-third has a diagnosis of a mental disorder. Others have life-threatening conditions, such as stage 4 cancer, leukemia, end-stage renal disease, or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (SSA, 2016). According to O’Leary et al. (2015), one-fifth of men and one-sixth of women who enter the program die within 5 years of entry. In 2015, 0.4 percent of workers’ SSDI benefits were terminated because of successful return to work (SSA, 2016).

The Social Security Supplemental Security Income Program

The SSI program, authorized by Title XVI of the Social Security Act and enacted in 1972, is a nationwide federal assistance program administered by SSA. It is funded through general revenues, and in addition to establishing disability, the applicant must also meet the nonmedical eligibility income and resource requirements, which are based on need. The basic purpose of the SSI program is to ensure a minimal income to people who are aged, blind, or disabled and who have limited income and resources. SSI recipients are also eligible to receive Medicaid coverage (without a waiting period as is the case with SSDI and Medicare coverage).5 In 2015, 985,913 disabled workers received both SSDI and SSI benefits; among them, the average monthly SSDI benefit was $559.07, and the average monthly SSI benefit was $225.08 (SSA, 2017c).

___________________

4 See https://www.ssa.gov/cgi-bin/currentpay.cgi, accessed February 1, 2018.

5 Some states have a separate process for determining Medicaid eligibility, but all states are required to offer Medicaid to disabled SSI beneficiaries. According to SSA in “most states, if you are an SSI beneficiary, you might be automatically eligible for Medicaid; an SSI application is also an application for Medicaid. In other states, you must apply for and establish your eligibility for Medicaid with another agency. In these states, we will direct you to the office where you can apply for Medicaid” (see https://www.ssa.gov/ssi/text-other-ussi.htm, accessed March 1, 2018 [SSA, 2017c]).

THE SOCIAL SECURITY DISABILITY DETERMINATION PROCESS

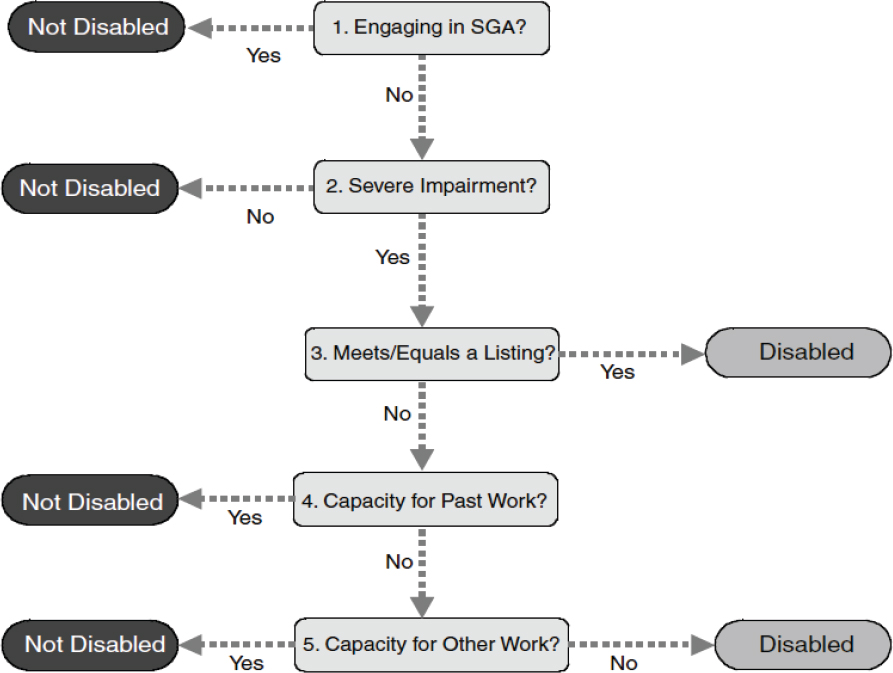

SSA has a five-step sequential process (see Figure 1-1) to determine whether someone is medically eligible for SSDI or SSI benefits (see Code of Federal Regulations, 20 CFR § 404.1520).

At the first step, SSA determines whether the applicant is currently engaging in substantial gainful activity (SGA), defined as earning more than the SGA threshold, which in 2017 was set at $1,170 per month for nonblind people and $1,950 for blind people (SSA, 2017d). If the applicant is currently engaging in SGA, SSA will find that the applicant is not disabled. At the second step, the disability examiner considers the medical severity and expected duration of the applicant’s impairment. If the applicant’s impairment or combination of impairments is not severe or has not lasted or is unlikely to last at least 12 months, SSA will find that the applicant is not disabled. At the third step, the disability examiner determines whether the impairment “meets” or “medically equals” one of the items on the Listing of Impairments (discussed in detail in the next section). If SSA finds that the applicant’s impairment meets or medically equals a listing, then SSA will find that the applicant is disabled and will receive a medical allowance.

NOTE: Substantial gainful activity (SGA) is defined as earning more than the SGA threshold, which in 2017 was set at $1,170 per month for nonblind people and $1,950 for blind people (SSA, 2017d).

SOURCE: 20 CFR § 404.1520 and 416.920.

Otherwise, the examiner moves on to the fourth step, at which point the disability examiner assesses the applicant’s “residual functional capacity” (the maximum level of physical or mental performance that the applicant can achieve given the functional limitations resulting from his or her medical impairment) and determines whether the applicant is able to engage in any of his or her past relevant work; if so, the applicant will be found not to be disabled (see CFR § 404.1560(b)).

At the fifth and last step, SSA will determine whether the applicant can perform any work in the national economy on the basis of the assessment of residual functional capacity and the applicant’s age, education, and work experience. If the applicant can make an adjustment to other work that exists in significant numbers in the national economy, SSA will find that the person is not disabled; otherwise, SSA will find that he or she is disabled (see CFR § 404.1560(c)). Figure 1-1 provides a visual model of the steps involved in the evaluation.6

Finally, it should be noted that SSA is committed to providing benefits quickly to applicants whose medical conditions are so serious that they obviously meet SSA’s disability standards. SSA has two fast-track processes—Compassionate Allowances (CALs) and Quick Disability Determination (QDD)—that enable SSA to expedite review and decisions for some applications. The CAL process incorporates technology to quickly identify diseases and other medical conditions that, by definition, meet SSA’s standards for disability benefits. Those conditions include certain cancers, adult brain disorders, and a number of rare disorders that affect children (SSA, 2017e). The QDD process uses a computer-based predictive model to screen initial applications and identify cases in which a favorable disability determination is highly likely and medical evidence is readily available in an effort to fast-track a (positive) determination (SSA, 2017f).

THE LISTING OF IMPAIRMENTS

The third step of the sequential evaluation process relies on the Listing of Impairments7 (hereafter Listings) to identify cases that can be allowed regardless of the applicant’s age, education, or work experience. The Listings are organized by 14 body systems for adults (see Table 1-1) and, for each system, includes impairments that SSA considers severe enough to prevent an adult from performing any gainful activity. According to the SSA Office of the Inspector General (OIG) (2015), “the Listings help ensure that disability determinations are medically sound, claimants receive equal treatment based on the specific criteria, and disabled individuals can be readily identified and awarded benefits, if appropriate.” Applicants whose impairments do not meet or medically equal a Listing can still be determined disabled at step 5 on the basis of the combination of their residual functional capacity, age, education, and work experience.

___________________

6 For additional details on the types of medical evidence considered in the disability-determination process and on the training and credentials required of disability examiners and medical/psychologic consultants, refer to The Promise of Assistive Technology to Enhance Activity and Work Participation (NASEM, 2017).

7 Found at 20 CFR Part 404, Subpart P, Appendix I.

TABLE 1-1 Body Systems in SSA Listings for Adults

| 1.0 Musculoskeletal system |

| 2.0 Special senses and speech |

| 3.0 Respiratory disorders |

| 4.0 Cardiovascular system |

| 5.0 Digestive system |

| 6.0 Genitourinary disorders |

| 7.0 Hematological disorders |

| 8.0 Skin disorders |

| 9.0 Endocrine disorders |

| 10.0 Congenital disorders that affect multiple body systems |

| 11.0 Neurological disorders |

| 12.0 Mental disorders |

| 13.0 Cancer (malignant neoplastic diseases) |

| 14.0 Immune system disorders |

SOURCE: Disability Evaluation Under Social Security (SSA, 2017b).

Although there has been an established “listing of medical impairments” since the disability program began in 1956, SSA did not publish the Listings in its disability regulations until 1968.8 Since then, it has revised the Listings periodically to reflect recent advances in medical knowledge. In 2003, SSA implemented a new process for revising the Listings, which was designed to ensure continuous updates and monitoring of the Listings about every 3–4 years (OIG, 2009). Seven body systems were last updated between 2009 and 2015. The SSA OIG recommended that by the end of fiscal year (FY) 2020, SSA should ensure that all Listings updates are less than 5 years old and that SSA continue to update them as needed to reflect current medical knowledge and advances in technology (OIG, 2015). Four more body systems (respiratory, neurologic, mental, and immune system disorders) were updated between 2016 and 2017.

After a body system is updated, SSA begins the process of identifying necessary revisions again. The process begins with information gathering within the agency (e.g., analyzing data, conducting a literature review, and obtaining feedback from adjudicators) and outside the agency (e.g., discussions with the public including medical experts and soliciting comments from the public via an Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking [ANPRM]. SSA develops proposed changes to the body system(s) based on its information gathering and case reviews, and drafts a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM). The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) as well as other federal agencies (e.g., the US Departments of Health and Human Services and Veterans Affairs) review and comment on the NPRM. SSA obtains OMB approval and publishes the NPRM in the Federal Register for public comment. SSA reviews and responds to public comments, revises the proposed rule as needed, and drafts a final rule. OMB reviews the final rule, and SSA obtains OMB approval and publishes the final rule in the Federal Register.

___________________

8 See https://secure.ssa.gov/poms.nsf/lnx/0434101005, accessed February 1, 2018, for an explanation of the Listing of Impairments before 1968 (SSA, 1990).

STATEMENT OF TASK

SSA asked the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to conduct a study of health-care utilizations by adults being evaluated for disability determination. The statement of task follows:

An ad hoc committee will provide an analysis of health care utilizations as they relate to impairment severity and SSA’s definition of disability. The committee will identify types of utilizations that might be good proxies for “listing-level” severity; that is, what represents an impairment, or combination of impairments, that are severe enough to prevent a person from doing any gainful activity, regardless of age, education, or work experience.

The task order objectives for the ad hoc committee are to

- Provide a general description of the health care delivery system (for example, the Affordable Care Act, move to patient-centered care, medical homes, bundled payments, and other significant changes in the delivery of care);

- Identify factors that influence a person’s use of health care services;

- Identify health care utilizations that represent, and are a good indicator of impairment severity for the purposes of the disability program;

- Explain how intervals between utilizations and duration of utilizations affect whether health care utilization is a good indicator of impairment severity;

- Explain how types of utilizations are more or less probable for particular medical conditions or combinations of medical conditions;

- Describe how factors such as poverty and urbanization level affect health care utilizations; and

- Describe how the health care utilizations interfere with a person’s ability to work.

During the committee’s meetings with SSA representatives, the committee came to understand that the study’s focus should not be on the content of the current Listing of Impairments, nor should it be a critique of SSA’s evidentiary requirements. SSA, in developing the statement of task, provided numbered objectives in an effort to provide needed guidance. SSA noted that it did not require recommendations, but the committee will present findings and conclusions. Furthermore, the committee was not tasked with examining functional outcomes or other objective performance measures. SSA does use such information when conducting assessments at steps 4 and 5 of the disability process. This report, however, is focused on step 3 of the disability process, that is, “whether the impairment ‘meets’ or ‘medically equals’ one of the items on the Listing of Impairments.”

APPROACH TO THE TASK

A 16-member committee was formed to address the task. Members with diverse backgrounds and expertise were appointed to focus on the different aspects of the task. Specifically, the members have expertise in various branches of clinical medicine (psychiatry and psychology, emergency medicine, neurology, gastroenterology, occupational medicine, family medicine, and cardiology) and in biostatistics and epidemiology, nursing, rehabilitation, disability research, health-care policy, and health economics.

The committee met five times. It sponsored two open meetings, which enabled SSA representatives and the committee members to interact directly and discuss the motivation for the study. The committee also invited people to address health-care trends and different viewpoints on the measurement of disability.

The committee considered the many different types of health-care utilization and the sites where they are delivered (see Appendix A) and whether and how they might be associated with severity of impairments (see Chapter 4). In support of the committee’s discussions and deliberations, the committee instructed the staff to conduct targeted literature searches, and information from relevant scientific, professional, and federal sources was gathered (see Appendix B). Staff reviewed more than 60,000 titles and abstracts; those were narrowed to about 700 studies, which the committee members carefully reviewed for relevance to the committee’s task. The papers that were determined to be most relevant to the committee’s task were summarized in Chapter 4 with details provided in Appendix C.

In an effort to approximate impairment severity, the committee reviewed the literature to consider to what extent and in which ways health-care utilization might reflect disease severity, disability, and ability to perform gainful activity. The committee recognized that varied access to health care potentially confounds any observed relationships, and it sought to identify predictors of health-care utilization to assist in understanding the context of the relationship between receipt of health-care services and ability to work.

Finally, the committee sought to understand both direct and indirect relationships between health-care utilization and ability to perform gainful activity. Direct relationships include the extent to which receipt of health-care services affects absenteeism and presenteeism. Indirect relationships are ones that suggest the extent to which health-care utilization can act as a proxy for severity of impairment and disability.

HEALTH-CARE UTILIZATIONS

People use health-care services for many reasons, for example, to cure or treat illnesses and health conditions, to prevent or delay future health problems, and to reduce pain and increase quality of life. Health-care utilizations might occur in traditional sites, such as hospitals, emergency departments (EDs), physician and dental offices, and nursing care facilities. However, they might also occur in less traditional sites, such as workplaces, urgent care facilities, and clinics (see Appendix A for a description of health-care utilization sites). Further, consumer preferences and new therapeutic technologies in new settings are changing how and where people obtain health care.

According to the National Center for Health Statistics (2003) the health-care delivery system has undergone many changes, even over the past decade. New and emerging technologies, such as drugs, devices, new procedures and tests, and imaging machinery, have changed patterns of care and created a shift in sites where care is provided. Improvements in anesthesia and analgesia and the development of noninvasive or minimally invasive techniques have caused a growth in ambulatory surgery. Procedures that formerly required a few weeks of convalescence now require only a few days, and new drugs can cure or lengthen the course of disease.

Health-care utilization has also evolved with changes in the population’s need for care. Some influencing factors include aging, shifts in population sociodemographics, and changes in the prevalence and incidence of various diseases. For instance, as the prevalence of chronic

conditions increases, so has the presence of residential and community-based health-related services designed to minimize loss of function and keep people out of institutional settings. The growth of managed care and payment mechanisms employed by insurers and other payers to control the rate of health care spending has also impacted health-care utilization. Efforts by employers to increase managed care enrollment, as well as major Medicare and Medicaid cost containment efforts have created incentives to shift sites where services are provided (NCHS, 2003).

TRENDS IN HEALTH-CARE UTILIZATION

Over the past few decades, delivery of care has changed markedly, with a general trend of a shift from inpatient care to outpatient care. Inpatient admissions have decreased substantially: hospitalizations have decreased from 36.2 million admissions in 1975 to 34.9 million in 2014 (NCHS, 2017), a decrease of about 35 percent in the number of admissions per unit of population in four decades. In the same period, the average length of stay has decreased from 11.4 days to 6.1 days.

In contrast, utilization of outpatient care has grown greatly over the past few decades. From 1975 to 2014, the number of outpatient visits (as defined as visits to physician offices, hospital outpatient departments, and hospital EDs) more than tripled, from 254.8 million to 802.7 million, and far outpaced population growth (NCHS, 2017).

Declines in hospital use and length of stay have been attributed to cost-containment measures instituted by Medicare and Medicaid programs, other payers, employers, and to scientific and technologic advances that allowed a shift in services from hospitals to ambulatory outpatient settings, the community, home, and nursing homes (NCHS, 2003). For example, ambulatory surgery centers, facilities that perform surgeries and procedures outside the hospital, were developed to provide high-quality, cost-saving care (ASCA, 2017). Technologic and clinical advances in chemotherapies and emerging methods in radiology have resulted in the shift of cancer care from hospitals to community outpatient settings (JHC, 2017). Those shifts toward incorporation of an increasingly available health-care technology are altering how patients access the health-care system (Ticona and Schulman, 2016).

It is important to note that overall utilization rates do not indicate what services are being provided to specific people and cannot serve as proxies for access to specific services or quality of care. A physician’s office visit could include tests, procedures, and even surgery, or it could consist entirely of a discussion with the physician. A hospital or nursing-home stay could be for diagnostic, palliative, or recuperative care or for medical or surgical interventions (NCHS, 2003).

Other changes in the nature of health-care utilization have been occurring. Inpatient hospitalization rates were similar in 1996 and 2006, for instance, but the prevalence of types of procedures has changed. Hospitalization rates for coronary artery stent insertions, hip replacements, and knee replacements rose sharply, and rates of some other procedures declined. Ambulatory surgery visit rates were almost twice as high in 2006 as in 1994–1996, and the increase in some types of ambulatory procedures, such as colonoscopies, was even greater (NCHS, 2010).

Health-care service use has increased in specific populations and for specific services. For example, the number of ED visits for patients who have mental health diagnoses have increased by 8.6 percent in a span of just 5 years, from 2006 to 2011 (Capp et al., 2016), and rates of visits for opioid use have risen dramatically (AHRQ, 2017). Similarly, the use of some

prescription drugs is increasing, particularly high-cost specialty and biologic drugs (Penington and Stubbings, 2016), as is multiple drug use (NCHS, 2017).

ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT

Chapter 2 examines the numerous individual and social determinants of health-care utilization. The regional determinants of health-care utilization are also explored. Chapter 3 discusses changing patterns of health insurance and health-care delivery and their potential effects on health-care utilizations. In Chapter 4, the committee considers whether health-care utilizations might be a proxy for impairment severity, and Chapter 5 discusses the ideal characteristics of a good proxy for listing-level severity.

There are three appendixes: Appendix A describes the different sites where health-care utilizations occur; Appendix B describes the search strategy that the committee used to identify and evaluate the scientific literature used in the report; and Appendix C provides detailed summaries of the literature reviewed in Chapter 4.

REFERENCES

AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality). 2017. HCUP statistical brief #219: Opioid-related inpatient stays and emergency department visits by state, 2009-2014. Rockville, MD: AHRQ. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb219-Opioid-Hospital-Stays-ED-Visits-by-State.jsp (accessed November 6, 2017).

ASCA (Ambulatory Surgery Center Association). 2017. ASCs: A positive trend in health care. http://www.ascassociation.org/advancingsurgicalcare/aboutascs/industryoverview/apositivetrendinhealthcare (accessed November 7, 2017).

Capp, R., R. Hardy, R. Lindrooth, and J. Wiler. 2016. National trends in emergency department visits by adults with mental health disorders. The Journal of Emergency Medicine 51(2):131–135.e131.

CBPP (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities). 2017. Chart book: Social Security disability insurance. Washington, DC: CBPP. https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/7-21-14socsec-chartbook.pdf (accessed November 6, 2017).

JHC (Journal of Healthcare Contracting). 2017. Cancer care migrates to outpatient setting. Journal of Healthcare Contracting.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2017. The promise of assistive technology to enhance activity and work participation. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https:doi.org/10.17226/24740.

NCHS (National Center for Health Statistics). 2003. Healthcare in America: Trends in utilization. Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/misc/healthcare.pdf (accessed March 1, 2017).

NCHS. 2010. NCHS data brief no. 32: Health care utilization among adults aged 55–64 years: How has it changed over the past 10 years? Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics (US). https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db32.pdf (accessed November 8, 2017).

NCHS. 2017. Health, United States. In Health, United States, 2016: With chartbook on long-term trends in health. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics (US).

OIG (Office of the Inspector General). 2009. The Social Security Administration’s Listing of Impairments audit report a-01-08-18023. Washington, DC: OIG. https://oig.ssa.gov/sites/default/files/audit/full/html/A-01-08-18023_7.html (accessed March 1, 2017).

OIG. 2015. Evaluation report: The Social Security Administration’s Listing of Impairments. Washington, DC: OIG. http://oig.ssa.gov/sites/default/files/audit/full/pdf/A-01-15-50022.pdf (accessed March 1, 2017).

O’Leary, P., E. Walker, and E. Roessel. 2015. Social Security Disability Insurance at age 60: Does it still reflect Congress’ original intent? Baltimore, MD: SSA. https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/issuepapers/ip2015-01.html (accessed March 1, 2017).

Penington, R., and J. A. Stubbings. 2016. Evaluation of specialty drug price trends using data from retrospective pharmacy sales transactions. Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy 22(9):1010-1017.

SSA (Social Security Administration). 1990. Di 34101.005 Listing of Impairments prior to August 1968-explanation. Woodlawn, MD: SSA. https://secure.ssa.gov/poms.nsf/lnx/0434101005 (accessed March 1, 2017).

SSA. 2005. Social Security bulletin, vol. 65, no. 4. Woodlawn, MD: SSA. https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v65n4/index.html (accessed March 1, 2017).

SSA. 2006. Trends in the Social Security and Supplemental Security Income Disability programs. Woodlawn, MD: SSA. https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/chartbooks/disability_trends/trends.pdf (accessed March 1, 2017).

SSA. 2010. The National Beneficiary Survey (NBS). Woodlawn, MD: SSA. https://www.ssa.gov/disabilityresearch/nbs.html (accessed March 1, 2017).

SSA. 2013. Fact sheet: Women who receive Social Security Disability Insurance benefits. Woodlawn, MD: SSA. https://www.ssa.gov/news/press/factsheets/ss-customer/women-dib.pdf (accessed March 1, 2017).

SSA. 2016. Annual statistical report on the Social Security Disability Insurance program, 2015. Woodlawn, MD: SSA. https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/di_asr/2015/di_asr15.pdf (accessed March 1, 2017).

SSA. 2017a. Understanding Supplemental Security Income SSI income 2017 edition. Woodlawn, MD: SSA. https://www.ssa.gov/ssi/text-income-ussi.htm (accessed March 1, 2017).

SSA. 2017b. Disability evaluation under Social Security: Listing of impairments-adult listings (part A). Woodlawn, MD: SSA. https://www.ssa.gov/disability/professionals/bluebook/AdultListings.htm (accessed March 1, 2017).

SSA. 2017c. SSI annual statistical report, 2015. Woodlawn, MD: SSA. https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/ssi_asr/2015/ssi_asr15.pdf (accessed March 1, 2017).

SSA. 2017d. Substantial gainful activity. https://www.ssa.gov/oact/cola/sga.html (accessed May 27, 2017).

SSA. 2017e. Compassionate allowances. https://www.ssa.gov/compassionateallowances (accessed March 1, 2017).

SSA. 2017f. Quick disability determinations (QDD). Woodlawn, MD: SSA. https://www.ssa.gov/disabilityresearch/qdd.htm (accessed March 1, 2017).

Ticona, L., and K. A. Schulman. 2016. Extreme home makeover—the role of intensive home health care. New England Journal of Medicine 375(18):1707–1709.