4

Current Financing for Early Care and Education: Affordability and Equitable Access (Principle 2)

This chapter reviews the current financing structure for early care and education against the committee’s second principle: high-quality early care and education requires that all children and families have equitable access to affordable services across all ethnic, racial, socioeconomic, and ability1 statuses as well as across geographic regions. First, it reviews current evidence on early care and education (ECE) usage and the affordability of early care and education for families. Next, the chapter discusses the adequacy of current financing to support access to high-quality early care and education and assesses whether the structure of provider-oriented and family-oriented financing mechanisms support equitable access to high-quality early care and education for all children from birth to kindergarten entry.

CURRENT ECE USAGE AND AFFORDABILITY FOR FAMILIES

Families’ current ECE usage patterns reflect the programs, costs, subsidies, and quality of currently available early care and education. Understanding current patterns of family use and expenditure helps to identify the gaps and problems in the current ECE financing structure. The changes envisioned in the Transforming report will undoubtedly lead to changes in the decisions families make with regard to using ECE services. As a result, the types of ECE providers chosen by families, the hours of care they use,

___________________

1 Ability status refers to special needs, including physical, emotional, and linguistic.

and their ECE expenditures will likely adjust, though only limited research is available on which to base predictions about those adjustments. Given this dearth of research, this section reviews families’ current use, which serves as a basis for predictions in Chapter 6 about changes in family use and expenditures in a transformed system.

Not all parents enroll their young children in nonparental care on a regular basis. The percentage of children with no ECE arrangements is highest for infants and declines as children approach kindergarten age. Nearly three-quarters of 4-year-olds have at least one regular ECE provider, compared to about half of 1-year-olds and 44 percent of infants under 12 months of age (Table 4-1). For some of these families, the decision not to rely on nonparental care is likely to be a choice based on preferences for parental care; other families feel they cannot afford nonparental care and that paying for such care would consume too much of their household budget. Still other families cannot find available nonparental care that meets their needs. For example, available and affordable ECE programs may only offer half-day programs that do not meet the needs of parents with full-time jobs, while some families live in areas that have a low supply of ECE programs or long waiting lists for the available programs. It is challenging to determine the extent to which preferences for parental care of infants versus the higher cost (and lower availability) of nonparental infant care options influence families’ decisions not to use the latter. Although utilization is driven by both the supply and demand for early care and education, it is difficult to disentangle the role of each. Box 4-1 discusses recent research on ECE availability and supply.

ECE usage patterns differ for low-income families compared to those with higher incomes. Both the proportion using regular nonparental early care and education of any type and the proportion using center-based care

TABLE 4-1 Weighted Percentage of Children with at Least One Regular ECE Provider, by Age

| Age of Children | Weighted Percentage |

|---|---|

| Less than 12 months old | 43.7 |

| 1 year old | 51.5 |

| 2 years old | 55.5 |

| 3 years old | 60.8 |

| 4 years old | 73.3 |

| 5 years old | 83.4 |

NOTES: See source for information on how the estimates were calculated, including weighting of percentages.

SOURCE: Based on Tables 1.00.1–1.05.1 in National Survey of Early Care and Education Project Team (2016a).

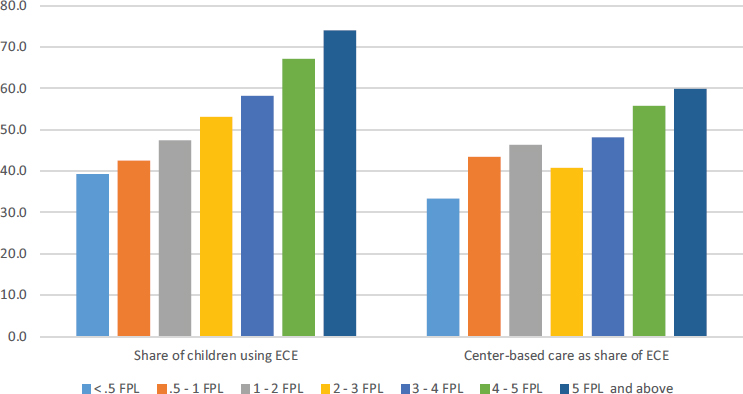

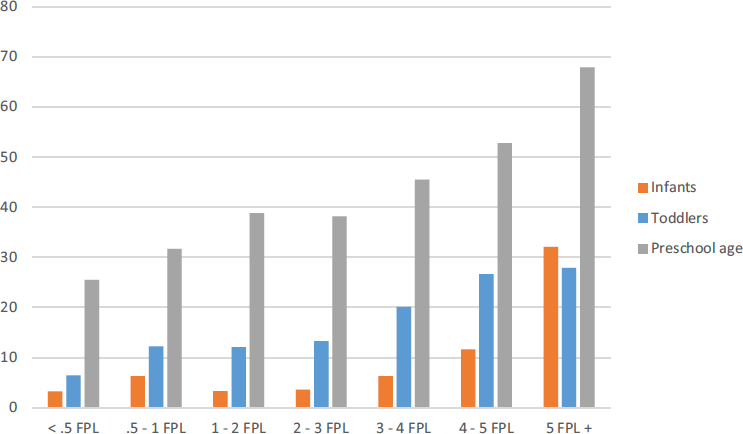

increase with income. As shown in Figure 4-1, the share of children in early care and education increases steadily with family income. Approximately two in five children in families with incomes below the federal poverty level (FPL) are in regular ECE arrangements, compared to nearly three-quarters of those with incomes more than five times the FPL. Of those in early care and education, the share in center-based (rather than home-based) care also increases with family income. Notably, however, families with incomes of 200 percent to 300 percent of the FPL who use regular early care and education are somewhat less likely to use center-based care than are lower-income families who qualify for public subsidies; they are much less likely to use center-based care than higher-income families. This “dip” in utilization suggests that a larger share of the families in this income range are unable to afford center-based care. Families with incomes between 300 and 400 percent of the FPL are also less likely to use center-based care than would be expected from the overall income trend. As Figure 4-2 shows, the proportion of children using center-based care is lowest for infants and

SOURCE: Based on Latham (2017), using data from the 2012 National Survey of Early Care and Education Public Data Set.

SOURCE: Based on Latham (2017), using data from the 2012 National Survey of Early Care and Education Public Data Set.

increases with age across the income groups, but it is always higher for higher-income than for low-income families.

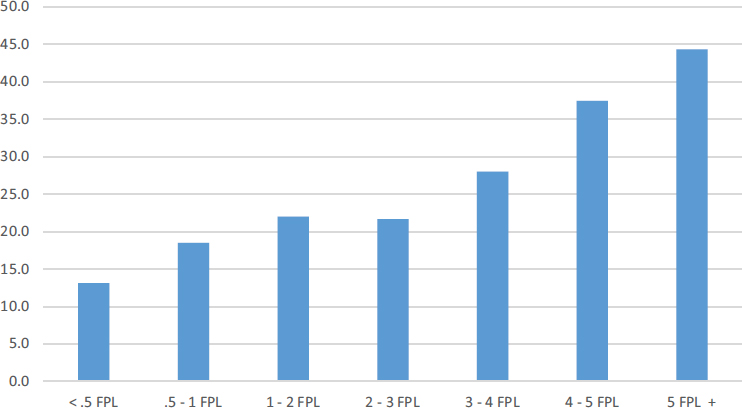

It is difficult to parse out the relative importance of budget constraints versus preferences in explaining these differences in ECE utilization patterns across income groups. Studies have found that low-income families use less center-based care than do high-income families and more often rely on relatives to provide care (Adams, Zaslow, and Tout, 2007; Burgess et al., 2014; Burstein and Layzer, 2007). Research has also found that low-income families often report reasons related to cost and convenience for selecting certain types of care, although some researchers argue that the type of care being used influences the reasons or preferences reported by parents (Chaudry, 2004; Chaudry et al., 2011; Henly and Lyons, 2000). The need for care during nonstandard working hours may also strongly influence the type of care used (Chaudry, Pedoza, and Sandstrom, 2012; Henly and Lambert, 2005). Overall, however, the rising utilization of center-based care with income shown in Figure 4-3, which on average is the most expensive type of early care and education (among those that charge parent fees) (National Survey of Early Care and Education Project Team, 2015d), supports the view that many low- and moderate-income families would use center-based care but currently cannot afford to do so. The jump in use of center-based care by families with incomes above 400 percent of the FPL

SOURCE: Based on Latham (2017), using data from the 2012 National Survey of Early Care and Education Public Data Set.

suggests that affordability is not just a problem for those with the lowest incomes (who may be eligible for free programs such as Head Start). Only about 20 percent of children in families with incomes up to 300 percent of the FPL are in center-based early care and education, compared to nearly 45 percent of those at 500 percent of the FPL.

While the focus of this discussion has been on the disparities in use of center-based care by income group, it is important to acknowledge that high- (and low-) quality care may be found in both center- and home-based settings (see e.g., Bassok et al., 2016).

The relationships between patterns of ECE use and family and child characteristics have been extensively studied and provide some insights into the factors influencing families’ selection of ECE service option. The type of early care and education that parents use has been found to correlate with child age, mother’s education, race and ethnicity, family income, and family structure (Chaudry et al., 2011; Forry et al., 2013). Patterns of ECE utilization also vary geographically across regions of the United States and in rural versus urban areas (Cochi Ficano, 2006; Gordon and Chase-Lansdale, 2001; Hofferth and Wissoker, 1992). These studies are unable to determine explicitly whether families choose to not use organized ECE options, or choose instead to use informal care, because of preferences, availability, or budget constraints. Nonetheless, comparing the utilization rates for paid care and center-based care across income levels provides information about the shortcomings of the current ECE financing system in the United States. The results suggest that families with lower incomes likely would increase their use of early care and education if it were more affordable.

Research has shown that increases in public funding for early care and education lead to increased use, particularly of formal or center-based care. For example, universal state-funded prekindergarten programs have been associated with increases in prekindergarten enrollment. Cascio and Schanzenback (2013) found that the state prekindergarten programs in Oklahoma and Georgia led to a large increase of about 20 percentage points in prekindergarten enrollment of children whose mothers had no more than a high school degree. Other studies have found that increases in state subsidy program and Head Start spending were associated with increases in use of nonparental care, especially formal care and center-based care (Greenberg, 2010; Magnuson, Meyers, and Waldfogel, 2007; Weber, Grobe, and Davis, 2014). Several studies have also demonstrated that families with access to subsidized ECE options use more center-based care, and higher quality care, than those without such subsidies (Berger and Black, 1992; Johnson, Ryan, and Brooks-Gunn, 2012; Krafft, Davis, and Tout, 2017; Marshall et al., 2013; Ryan et al., 2011).

Parents use ECE services to provide educational and social experiences for their children. In addition, many need care for their children while the

parents are working (or in educational or training programs). For working parents, the ECE hours used and the timing of those hours during the week depend at least in part on the parent(s)’ work schedule. Hours used in center-based care are mostly during standard business hours (Monday through Friday, 8 a.m. to 6 p.m.), likely as a result of many centers not operating outside those hours. Only 8 percent of center-based programs offer early care and education on any evening or during weekend hours (National Survey of Early Care and Education Project Team, 2015b). If parents need care for young children in the evenings or weekends, they rely mostly on home-based care. At the same time, some education-focused ECE programs provide services only on a part-day or part-week basis, so they may be difficult for working parents to use. For instance, most prekindergarten programs are like K-12 education in not offering summer care, which is a major challenge for working parents.

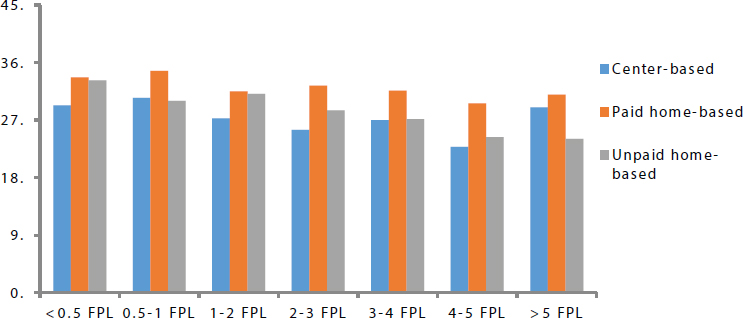

For those who use early care and education of any kind, the typical patterns of hours of care vary across income levels and age groups. Based on an analysis of data from the National Survey on Early Care and Education (see Table 4-2), children are in early care and education an average of 34 hours per week between ages 1 and 5 (and excluding those in kindergarten). Average hours in paid home-based and center-based care decrease with the age of the child, reflecting the increasing use of part-time care for children as they age from 36 to 60 months (e.g., for children whose mothers do not work outside the home and send their children to prekindergarten). This increased use of part-time care for older children could be in part because some Head Start and public prekindergarten programs are only offered on a part-day basis, on a school-year basis, or both. The average number of hours used are similar in paid home-based settings and center-based settings, with somewhat shorter hours on average in unpaid home-based

TABLE 4-2 Average Weekly Hours of Care per Child, by Age Group and Type of Early Care and Education

| ECE Option | All Children | Age Less than 12 Months | Child Ages 12–36 Months | Child Ages 36–60 Months and Not in Kindergarten |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 33.9 | 34.2 | 35.1 | 32.9 |

| Center-based | 27.7 | 36.3 | 31.3 | 25.7 |

| Paid home-based | 31.9 | 34.5 | 34.0 | 28.2 |

| Unpaid home-based | 29.1 | 28.0 | 29.4 | 29.4 |

SOURCE: Data from Latham (2017, Table 1.1.0), using data from the 2012 National Survey of Early Care and Education Public Data Set.

SOURCE: Data from Latham (2017, Table 1.1.1), using data from the 2012 National Survey of Early Care and Education Public Data Set.

settings. The average weekly hours of care are fairly consistent across income groups and types of care (see Figure 4-4).

The stark difference in ECE utilization pattern across income categories supports the hypothesis that the cost to families is an important determinant of children’s access to early care and education. The committee agreed that, given the importance of high-quality early care and education for child development, children’s access to high-quality ECE opportunities should not be constrained by their family’s income. Yet, determining what level of ECE expenditure is affordable to families is challenging for a number of reasons. There is no universally accepted definition of affordability for ECE services, nor is there agreement on how it should be measured. Definitions for affordability of housing, health care, and higher education face similar challenges (see, e.g., Harkness and Newman, 2005).2 The committee reviewed four different approaches to determining a reasonable share for families to pay, or in other words, four ways of defining an affordability standard for families. These approaches include: (1) no-fee approaches, (2) share of income based on equitable cost burden, (3) share of income after protecting for necessities (also called a “basic-needs budget approach”), and (4) affordability as minimizing impact on utilization decisions (also called an “economic modeling approach”). The advantages and disadvantages of these approaches are discussed in Appendix C.

Many complexities arise in defining an affordable share for families to

___________________

2 In presentations to the committee, representatives from the health care, housing, and higher education fields discussed definitions of affordability in their sectors.

pay, in terms of defining both family income and payments and in setting the threshold that defines affordability (e.g., should the threshold differ based on family needs or characteristics?). The share of income families spend on early care and education varies with their resources, needs, and preferences. The no-fee approach eliminates financial barriers to accessing certain ECE programs and ensures access to early care and education, regardless of family circumstances, but higher levels of public funding would be needed to support a system based on this approach (see the discussion in Chapter 6 on “Example Part II: Family Payments in a High-Quality ECE System”). While the committee does not propose using a particular definition of affordability, we agreed that the recommendations for financing and system changes discussed in this report must enable families at all income levels to access high-quality ECE services for their children at all ages from birth to 5 years old.

FINANCING MECHANISMS’ SUPPORT OF EQUITABLE ACCESS

This section analyzes the adequacy of existing provider-oriented (Head Start and state-funded prekindergarten) and family-oriented (ECE assistance programs and tax preferences) financing mechanisms to support access to high-quality early care and education. It also assesses whether these financing mechanisms as currently structured support equitable access to high-quality early care and education for all children across all ethnic, racial, socioeconomic, and ability statuses as well as across geographic regions.

Provider-Oriented Financing Mechanisms

This section analyzes the two major programs that distribute funds through provider-oriented mechanisms: federal-funded Head Start programs and public prekindergarten programs that are funded primarily by states or local jurisdictions (see Chapter 2 for details on these programs). Head Start funding is designed to cover the entire cost of early care and education for participating children, and eligible families pay no share of the cost. Public prekindergarten programs vary by location; some require no payment by any parents with children in the program, others require some payment by some but not all parents, and still others require some payment by all parents.

Existing provider-oriented mechanisms generally are designed to promote access to early care and education for low-income children. Families are eligible to enroll their children in a Head Start program if their income is below a certain level (see Chapter 2); likewise, many—though not all—public prekindergarten programs are also targeted to low-income children. Though targeted to low-income families, many of these programs are underfunded and do not serve all children who are eligible to receive

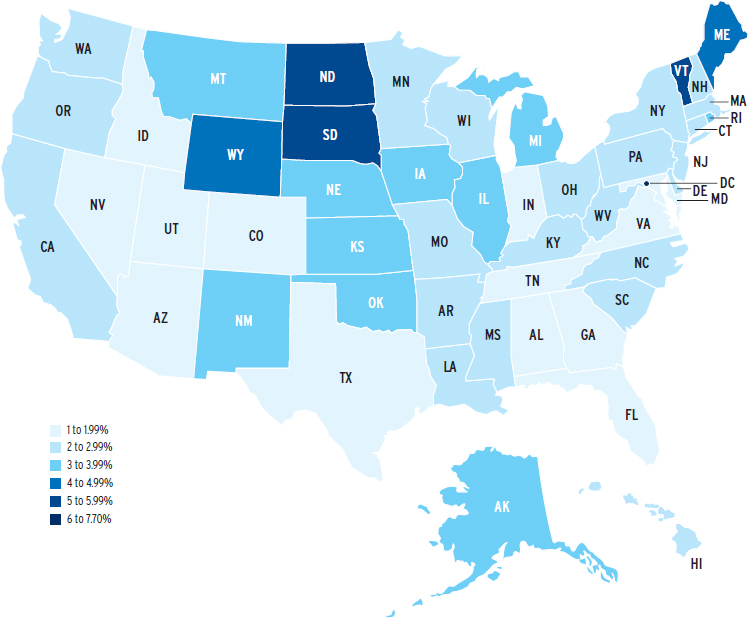

SOURCE: Barnett and Friedman-Krauss (2016, p. 11).

services. In fiscal 2016, only 31 percent of eligible children ages 3 to 5 years were served by Head Start (National Head Start Association, 2017), and participation varied greatly by state, as shown in Figure 4-5. Similar variation exists for state-funded prekindergarten programs. For example, three states (Florida, Oklahoma, and Vermont) and the District of Columbia cared for greater than 70 percent of their 4-year-olds in state-funded prekindergarten programs in 2012–2013, while 11 states served less than 10 percent of their 4-year-olds (U.S. Department of Education, 2015).3 For low-income4 children under 3 years old, less than 3 percent were served by Early Head Start in 2014–2015 (Barnett and Friedman-Krauss, 2016). According to Barnett and colleagues (2017, p. 8), “Across all public

___________________

3 The 11 states are Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Delaware, Minnesota, Missouri, Nevada, Ohio, Oregon, Rhode Island, and Washington.

4Barnett and Friedman-Krauss (2016, p. 12) defined low-income families as having household incomes between zero and 200 percent of the FPL.

programs—[prekindergarten] general and special education enrollment plus federally and state-funded Head Start—43 percent of 4-year-olds and 16 percent of 3-year-olds were served.”5

Moreover, according to Schmit and Walker (2016, p. 12), “only half of eligible Black preschoolers, 38 percent of eligible Hispanic/Latino children, and 36 percent of eligible Asian children were served through Head Start.” Early Head Start programs provided even less access to eligible children, with “6 percent of eligible Black infants and toddlers, 5 percent of eligible Hispanic/Latino infants and toddlers, and 4 percent of eligible Asian infants and toddlers being served.”6 While targeting low-income children responds to one aspect of equity, current provider-oriented mechanisms are insufficient to support access for all low-income families and do not address the middle-income gap.

For eligibility, both Head Start and public prekindergarten focus on the developmental needs of children, rather than the employment status of their parents. Thus, children are eligible for service if they meet income and/or geographic requirements regardless of parental employment or participation in education or training.7 However, because the main goal of these programs is to support child development and not specifically parental employment, many of these programs do not serve children on a full-day, full-year basis. The duration of service varies by type of setting (state-funded prekindergarten or Head Start) and across states. Therefore, many families rely on a combination of provider-oriented and family-oriented mechanisms to meet their ECE service needs while working. Head Start regulations also require programs to serve children who have special physical, emotional, or developmental needs (see Box 4-2 for a discussion of financing mechanisms available to support the provision of services for these children).

Because Head Start and public prekindergarten are provider-oriented, they can potentially target ECE opportunities and build supply in high-need

___________________

5Barnett and Friedman-Krauss (2016, p. 18) estimated that serving half of all low-income children in the United States in Head Start would cost $20 billion, an increase of $14.4 billion in federal investments.

6Schmit and Walker (2016) noted that Head Start administrative data report race and ethnicity separately, which prevents identification of White non-Hispanic/Latino children. As a result, Schmit and Walker (2016) did not provide an analysis of access for White children. Without an analysis of access for White children, it is difficult to determine whether the shares of children served specifically reflect underservice of non-White children or reflect the overall underfunding of the program.

7 Basing eligibility on income without regard to parent employment has advantages for increasing access, but it is not something inherent in the choice between provider-oriented and family-oriented financing. Rather, the requirement of parental employment or education/training to receive certain types of assistance is an artifact of the financing being situated in the work-welfare policy sphere and the dual ECE objectives of fostering child development and adult employment (see Chapter 2).

communities, which can improve access for low-income children in those areas. Funds can be distributed contingent upon the location of the ECE program and can thus incentivize the creation and maintenance of programs in high-need areas. For example, approximately 50 percent of centers in moderate- and high-poverty areas participate in Head Start or public prekindergarten programs, whereas about one-third of centers in low-poverty areas have such programs. Similarly, about 50 percent of centers in rural areas take part in Head Start or public prekindergarten programs, whereas only 30 to 40 percent of centers in moderately or highly urban locations take part in those programs (National Survey of Early Care and Education Project Team, 2015c).

However, this uneven distribution of programs may disadvantage some low-income families who do not live in an area with Head Start or public prekindergarten programs, though this limitation is not inherent in the mechanism itself but is a result of current design. Moreover, the targeting of public funds to low-income families through provider-oriented mechanisms may promote racial and economic segregation, which may have negative effects on low-income children (see, e.g., in the K–12 context, Bifulco and Ladd, 2007; Ladd, Clotfelter, and Holbein, 2017; Saporito, 2003). For example, some Head Start providers serve only low-income children, creating a divide between these children and other children in their community who attend non–Head Start programs. Although other Head Start providers serve both Head Start–eligible and–ineligible children, the same economic segregation still often occurs within the center. Many providers establish separate classrooms for eligible and non-eligible children, largely due to the difficulty of applying different staffing and service standards associated with various program requirements, which furthers economic segregation and has implications for quality.

Family-Oriented Mechanisms for Service Delivery

Family-oriented mechanisms may help address issues of equitable access to early care and education by providing assistance for low- and moderate-income families who would otherwise be unable to afford paid ECE services. However, how these mechanisms are structured is important for ensuring equitable access; if a mechanism is structured so that small increases in earnings produce a large drop in benefits, then this “cliff effect” creates a work disincentive and may limit access to early care and education for certain families.8 For example, Child Care Assistance Programs (CCAP)

___________________

8 A related concern is the presence of a “notch” in benefit schedules, where benefits do not increase or decrease smoothly as income increases, due to consideration of other family factors. This type of notch can produce inequities within families of similar socioeconomic status (sometimes called “horizontal inequities”), where families of similar circumstances are treated differently.

funds are structured to be issued on a sliding scale based on family size and income (e.g., subsidies to larger families with lower incomes are higher than subsidies to smaller families with higher incomes), which reduces the “cliff effect” and the likelihood that a low-income family will lose benefits if family income increases. Conversely, in a program like Head Start, in which early care and education is provided on a no-fee basis for families with incomes up to the FPL, if a family’s earnings increase slightly above the FPL, that family will no longer be eligible to participate in Head Start in the next school year. Even if families live in a state that offers CCDF assistance to families with income somewhat above the FPL, that assistance would be small in comparison to what they received from Head Start, potentially making ECE participation unaffordable for them.

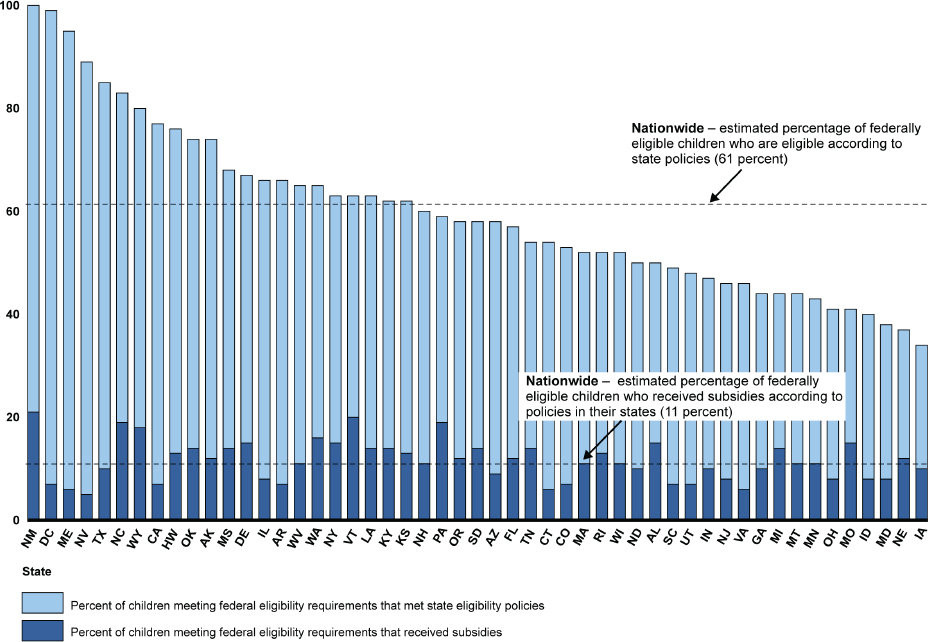

State ECE assistance programs also require copayments, limiting the ability of those programs to support ECE participation for some families. In some states, copayment levels are so high that low-income families may be unable to afford early care and education, even with the subsidy. Moreover, although the federal government sets the maximum income level for assistance at 85 percent of the state median family income, most states have established even lower income-eligibility levels, preventing some low-income families from accessing the state ECE subsidy. For example, a family with an income greater than 200 percent of the FPL9 would not be eligible for financial aid in 39 states (Schulman and Blank, 2016); that family would fall into the middle-income gap in use of center-based care, as discussed above. In fact, only 11 percent of children who are eligible for assistance receive it (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2016).10 To manage the difference between available funds and needs, 20 states instituted waiting lists or froze intake for eligible families in 2016 (Bipartisan Policy Center,

___________________

9 In 2015, 200 percent of the FPL for a family of three (one child) would be an annual income of $40,320.

10 Moreover, an analysis of the cost implications of changes made in the 2014 reauthorization of the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG) Act suggests that in order to implement the changes required in the act, the annualized costs, averaged over a 10-year period, would total $1.16 billion. The estimated increases in subsidies needed to meet all requirements for the currently served child population would amount to an additional $7.4 billion over 10 years. However, this figure would not increase the number of children served. Therefore, the cost of financing these changes and helping all eligible children is likely much higher. (See: https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2016-09-30/pdf/2016-22986.pdf [December 2017]). Similarly, the National Women’s Law Center notes, “For states to comply fully with the new requirements of the reauthorization while avoiding tradeoffs that harm children and families—and the child care providers who serve them—it will be essential for policymakers to appropriate significant new federal and state resources” (Matthews et al., 2015, p. 4). While CCDBG appropriations increased by roughly $300 million in 2016, this amount is lower than the estimated cost of implementing the new standards. (See: https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/5-19-17bud_childcare.pdf [December 2017]).

2017; Schulman and Blank, 2016). Figure 4-6 shows the percentage of children eligible for federal CCAP assistance who also qualify under state policies and receive assistance. Using state income eligibility criteria, Schmit and Walker (2016, pp. 12–13), estimated that “only 21 percent of Black children, 11 percent of Asian children, 8 percent of Hispanic/Latino children, and 6 percent of American Indian/Alaskan Native children” eligible for assistance were served through CCAP.11 If federal eligibility criteria were used (85 percent of state median income), the data would show even lower rates of provided services to eligible children.

Further, CCAP assistance and federal tax preferences are restricted by federal law to families with parents who are employed or participating in education or training programs, further reducing access to financial support for some families. States vary in terms of requirements for hours of work and in their determinations of which activities parents can undertake while using CCDF funds for early care and education, particularly regarding what qualifies as education and training, or if self-employed, what work qualifies as an allowable activity. Moreover, children who are U.S. citizens in mixed status families (i.e., not all family members have lawful entry status) will be ineligible for CCDF funds because their undocumented parents cannot legally meet the work requirement (Adams and Matthews, 2013). Many other family circumstances besides employment can make participation in early care and education desirable for children (such as parental desire to enable their children to engage socially with other children, fostering school readiness through structured early learning, or supporting parents in poor health or parents who care for other family members). The employment requirement for family-oriented assistance unnecessarily restricts access to ECE financial support only to children whose parents meet certain eligibility requirements, including employment.

Furthermore, eligibility requirements that are tied to parental employment rather than children’s developmental needs may increase instability in ECE arrangements. If a parent loses his or her job, the children may be unable to participate in early care and education. The 2014 reauthorization of the CCDBG Act addressed this issue with new eligibility determination rules, which allow a 3-month window before a previously eligible family

___________________

11 Like Head Start administrative data, CCDBG administrative data do not report race and ethnicity separately, which prevents differentiation of White non-Hispanic/Latino children from White Hispanic/Latino children. As noted above in footnote 6 to this chapter, this prevented Schmit and Walker (2016) from providing an analysis of access for White children. Again, without an analysis of access for White children, it is difficult to determine whether the shares of children served specifically reflect underservice of non-White children, or whether they reflect the overall underfunding of the program.

SOURCE: U.S. Government Accountability Office (2016, p. 10).

becomes ineligible.12, 13 Although these changes are beneficial to CCDF providers and families, other programs and tax preferences lack this stability.

Family-oriented financing mechanisms can also allow financial support to be tailored to a family’s circumstances and thereby promote target efficiency. For example, an ECE program that provides subsidies on a sliding scale that decreases with greater income and increases with larger family size (though restricted to parents who are employed or in education or training programs) aims to limit assistance to the amount “needed” by a family, thereby targeting scarce public resources to those most in need. Although provider-oriented supports may also be tailored to family circumstances, they typically do so in a cruder way, such as imposing income eligibility restrictions or by using neighborhood characteristics as a criterion for locating publicly supported ECE facilities (Ladd, 2017).

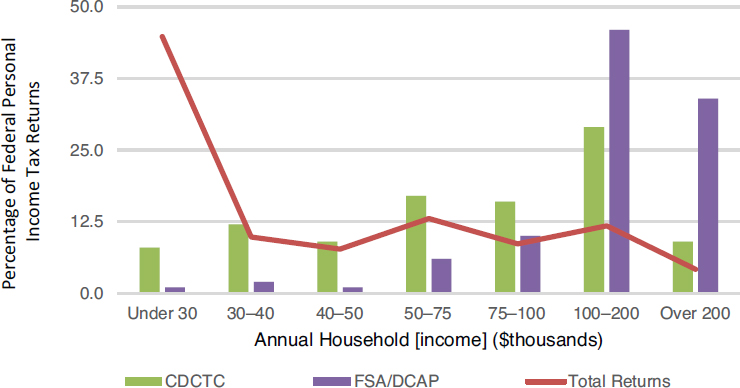

As currently designed, tax preferences including the Child Care and Dependent Tax Credit (CDCTC), Dependent Care Assistance Program (DCAP), and state equivalents are more beneficial for middle- and upper-income families than for low-income families. The DCAP allows for a reduction in taxable income, rather than a reduction in tax payments, as would be the case for a tax credit. Moreover, the CDCTC is a nonrefundable tax credit, and because many low-income families have little or no federal tax liability they are unable to benefit from the credit (see Figure 4-7) (Brown and Medoff, 1989; Matos and Galinsky, 2012).14

While DCAP’s allow taxpayers to reduce the amount of their taxable gross income, they do little to benefit low-income families who already have zero income tax liability because of their low incomes. Similarly, since the CDCTC is not “refundable” (paying an amount in excess of tax liability), it has no value for low- or moderate-income families with no federal income tax liability (even though these families do pay a substantial share of their income in social insurance payroll taxes). Of course, redesigning the CDCTC to make it refundable would benefit low- and middle- income families and has been done in some states for that state’s ECE-related tax

___________________

12S. 1086 Child Care and Development Block Grant Act of 2014, 113th Cong., 2nd Sess. Available: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/occ/ccdbgact.pdf [September 2017].

13 The language in the 2014 CCDBG Act reauthorization notes, “getting and keeping CCDF assistance is overly burdensome for parents, resulting in short durations of assistance and churning on and off CCDF as parents lose assistance and then later return. This instability disrupts parental employment and education, harms children, and runs counter to nearly all of CCDF’s purposes.”

14 The large share of low-income tax filers receive hardly any ECE benefits partly because many of them have no income tax liability. Moderate-income families ($30,000–50,000) receive a share of CDCTC benefits roughly proportional to their share of returns, but hardly any DCAP benefits. Both CDCTC and DCAP benefits are favorable to families making $100,000–200,000 per year, and DCAPs are favorable to wealthy families making more than $200,000 per year.

NOTE: CDCTC = Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit, DCAP = Dependent Care Assistance Program, FSA = Federal Student Aid.

SOURCE: Data from Tax Policy Center (2016, 2017).

credit, as discussed in Chapter 2. Timing and administrative requirements also present major concerns for using tax preferences as a mechanism to support ECE access for low- or moderate-income households. More-affluent families with substantial discretionary income can afford to pay ECE expenses on a weekly or monthly basis (the most common ECE provider billing cycles) and recoup the tax preference as a reduction to their tax payment or increase in their refund with their annual tax filing. Low- and moderate-income families typically do not have the ability to pay costs as incurred and recoup the costs later.

CONCLUSION

In their current form, both provider-oriented and family-oriented mechanisms can help improve ECE access. Head Start and some state prekindergarten programs improve access by targeting program location to high-need areas and to some low-income (high-need) families because they charge no fees to program-eligible families. In addition, because they usually deliver early care and education to families either on a no-fee basis or for a minimal copayment, they reduce or eliminate barriers to ECE use attributable to the family’s inability to pay. While targeting these resources to low-income families has benefits and contributes to equity of access,

these programs often leave middle-income families without access to affordable high-quality early care and education, which may promote economic segregation. To the extent that prekindergarten programs are universally provided, meaning they are provided for free to all children in the target age range, they do not exacerbate inequality in access.15

As currently structured, the family-oriented mechanisms of tax preferences benefit middle- and upper-income families to a greater degree than low-income families, which typically have little or no income tax liability prior to applying a tax credit or reducing taxable income with pretax contributions. The exception to this generalization are the refundable ECE credits provided by several states. In contrast, CCAP are targeted only to low-income families. However, in states with very low income eligibility standards, many families may not be able to access the CCAP, even though they are unable to afford ECE without assistance.

In addition to the drawbacks specific to these mechanisms in their current form, there are disadvantages in the overarching situation that the existing ECE “system” is a hodgepodge of various programs with varying and conflicting eligibility criteria and reimbursement approaches. Because no system is well structured enough to address the ECE needs of all children, families may be caught between the criteria and limitations of the individual ECE options available to them. For example, a family that has an income above the FPL may not be eligible for Head Start, but that family’s taxable income may be too low to benefit from nonrefundable tax credits. Eligibility requirements also vary between programs and can result in instability in a child’s ECE participation when a family’s circumstances change. Moreover, current requirements conditioning CCAP assistance and federal tax preferences on parental employment (or participation in approved venues for training or education) limit the ability of some children to access early care and education.

The inadequacies of the current funding structure stem not necessarily from having multiple financing mechanisms but from relying on mechanisms that are not harmonized to avoid gaps in affordable access. These gaps are exacerbated by overall levels of funding that are insufficient to support either provision of high-quality early care and education or its affordability by families at all income levels (see Chapter 6) and by considerable variation in quality standards and funding across states and among provider entities (Bassok et al., 2016). Chapter 5 considers these questions of quality in greater detail.

___________________

15 However, universal programs, depending upon duration offered, may improve access to high-quality early care and education for only a limited number of hours per day, in which case families needing additional hours of care may need assistance to access additional or alternative ECE services.

This page intentionally left blank.