1

Introduction

Investments in the early care and education1 of children from birth to kindergarten entry are critical to positive child development and have the potential to generate economic returns that benefit not only children and their families but also society at large. Traditionally, the provision of early care and education in the United States has had three goals: (1) to promote healthy child development and learning, (2) to provide parents the opportunity to fully participate in the economy, and (3) to develop human capital and prepare the nation’s children to be productive members of the future workforce. In pursuit of these aims, early care and education may be considered both a child-development and economic-development strategy, yielding returns to society that exceed the resources invested and realizing the promise and utility of early investments in children (see, e.g., Garcia et al., 2017; Karoly, Killburn, and Cannon, 2005).

Early care and education (ECE) investments are critical because the early foundation needed for success in school and later in life is built during the beginning years of a child’s life. During this period, brain development and early learning occur rapidly and are greatly influenced by environments, experiences, and relationships. Each interaction an infant, toddler, or prekindergartner has with the adults in his or her life can influence neural, cognitive, and social and emotional development. It is a period of

___________________

1 Early care and education can be defined as nonparental care that is occurring outside the child’s home. Given the report’s focus on financing, the committee discusses only paid, nonparental care. ECE services may be delivered in center-based settings, a school-based setting, or home-based settings. See the section below on “Defining Early Care and Education.”

incredible opportunity, where stimulating interactions, within the context of securely attached relationships, can put children on a positive trajectory (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2015). Thus, not only families but also society more broadly depend on ECE programs and the ECE workforce to enable parents’ participation in the workforce and to promote early learning and positive childhood development aimed at maximizing the potential of children and ensuring their futures as positive contributors to society. However, despite the great promise of investments in early care and education, its current financing structure only allows it to serve a fraction of the families who need high-quality care and hampers the development of a stable, highly qualified, and high-quality ECE workforce, making the financing structure neither sustainable nor adequate to provide the quality of care and learning children and families need. The consequences of this long-standing approach to financing have left many families without access to affordable, high-quality early care and education, perpetuating and driving inequality.

Early care and education enables parents to be employed and thus provides them an opportunity to contribute to the economy of the nation. Today, 82 percent of children live in households where all parents are employed (National Women’s Law Center, 2014; Women’s Bureau, 2016). As a result, children spend an average of about 34 hours a week in some type of ECE arrangement (Latham, 2017). These figures indicate that young children spend a significant amount of time in early care and education, making professionals in these settings stewards of critical investments in children and critical agents in children’s learning and development. Given the prevalence of children growing up in households with working parents, families increasingly depend on ECE programs and the professionals in these settings to promote learning while they are working.

Moreover, for low-income families, early care and education can provide a critical avenue out of poverty by enabling parents to work and support their families. Today, more than 5 million (or approximately 1 in 5) children in the United States under the age of 6 live in poverty (Jiang, Granja, and Koball, 2017). These numbers are of particular concern because child poverty has been linked to lower academic performance and behavioral problems. According to the Children’s Defense Fund, expanding access to high-quality early care and education has the potential to reduce the child poverty rate2 by 3 percent (Giannarelli et al., 2015). Thus,

___________________

2 Unless otherwise defined, “poverty rate” means the fraction of a group that lives under a specific ceiling-threshold level for poverty. In this case, the threshold for poverty is defined using the Census Bureau’s Supplemental Poverty Measure as “the mean of expenditures on food, clothing, shelter, and utilities over all two-child consumer units in the 30th and 36th percentile range, multiplied by 1.2” (Renwick and Fox, 2016, p. 2).

investments in high-quality early care and education contribute to the nation’s economy by making it easier for low-income parents to work, which has the potential to reduce child poverty and guard against its developmental consequences.

Beyond supporting positive child development and parents’ involvement in the current workforce, early care and education is also an investment in human capital. Investments in early care and education develop the nation’s future skilled and qualified workforce to meet the needs of employers and the economy. The economic growth and prosperity of the nation depends on sustaining and enhancing a workforce that is productive and can compete with workers in other countries in an increasingly globalized world. To meet the economy’s need for a skilled workforce, investment in the early care and education of children is critical.

Increasing the qualifications and compensation of ECE educators would address the problem of a large share of the ECE workforce living in poverty. The ECE workforce comprises nearly 2 million practitioners, almost all of whom are women and many of whom live below the federal poverty level and rely on public subsidies to support themselves and their families. Investments in early care and education serve to promote the professionalization of this workforce and increase wages, reducing the economic strain facing those entering the field.

Studies show that disparities across socioeconomic and racial/ethnic groups in cognitive skills, health, behavior, and school readiness are apparent before children enter kindergarten (Reardon, 2011; Reardon and Portilla, 2016). This growing gap can be partly attributed to disparities in access to opportunities, as higher-income families have increased investments, including enrolling their children in early education, whereas high-quality early care and education remains inaccessible or unaffordable for many middle- and low-income families (Chaudry et al., 2017). As a result of these disparities, children may be placed in lower-quality early care and education that does not enhance learning and development or may even be harmful to their development. The inability of all American families to access affordable, high-quality early care and education increases the poverty rate among children and contributes to gaps in later educational outcomes across socioeconomic and racial/ethnic groups, resulting in a greater likelihood of lifelong poverty for these children.

Given these challenges, transforming the financing structure for early care and education to meet the needs of all children and families will require significant mobilization of financial and other resources. Assessments of resource needs, investments from government and nongovernmental sources, financing innovations, and changes in the ECE system will all be important. In short, the necessary changes will not come quickly, easily, or without

cost, but they are nonetheless critical to achieve if U.S. society is to realize the benefits of early care and education.

CHARGE TO THE COMMITTEE

To this end, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine appointed the Committee on Financing Early Care and Education with a Highly Qualified Workforce to prepare a report that would outline a framework for a funding strategy that will provide reliable, accessible high-quality early care and education for young children from birth to kindergarten entry, including a highly qualified and adequately compensated workforce that is consistent with the vision outlined in the 2015 Institute of Medicine and National Research Council report Transforming the Workforce for Children Birth Through Age 8: A Unifying Foundation (the Transforming report); the committee’s complete statement of task

appears in Box 1-1. The Transforming report made recommendations to build a foundation for the workforce based on essential features of child development and early learning and on principles for high-quality professional practice at the levels of individual practitioners, practice environments, leadership, systems, policies, and resource allocation.

Funding for the committee’s study and report was provided by the Alliance for Early Success; the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; the Buffett Early Childhood Fund; the Caplan Foundation for Early Childhood; the Foundation for Child Development; the Heising-Simons Foundation; the Kresge Foundation; the U.S. Department of Education; and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Administration for Children and Families; and with additional support from the Bruce Alberts Fund, the Cecil and Ida Green Fund, and the W.K. Kellogg Foundation Fund.

In undertaking the charge, the committee reviewed and synthesized available research on the resources needed to meet the costs of high-quality

early care and education, including resources for improving the quality, affordability, and accessibility of higher education for the ECE workforce; improving the quality and availability of professional learning during ongoing practice; and supporting well-qualified educators and administrators with adequate compensation through complete wage and benefit packages that are comparable across settings and children’s ages.

The committee examined existing funding structures and mechanisms as well as promising approaches at the national, state, and local levels. It reviewed existing costing tools and frameworks that support national, state, and local systems in developing financing mechanisms unique to their contexts. In addition, the committee considered evidence from international early care and education and from other sectors (see discussion below) to inform its analysis and recommendations on how to finance early care and education for children from birth to kindergarten entry that is accessible, affordable to families, and of high quality.

The committee’s charge specifically asks it to provide a vision for financing that is consistent with the Transforming report’s conclusions and recommendations, which were based on that committee’s assessment of the available evidence, in the context of an evolving science and research base as well as an evolving policy and practice landscape in early care and education. While this committee acknowledges that there have been a range of perspectives in the field (as well as among this committee’s members) as to the prudence of the Transforming report’s recommendations about qualification requirements, it was not asked to review the evidence undergirding that report’s recommendations. Adhering to our charge, this committee studied and analyzed the best ways to approach the financing of the Transforming report’s recommended changes (see discussion below).

The committee was not asked to carry out new comprehensive costing analyses of the approaches it considered or of its conclusions and recommendations. In line with the study’s scope, the committee outlined a structure and set of principles for financing that would inform context-specific costing. The committee also adapted existing cost calculators to produce an illustrative estimate of aggregate national cost. This illustrative example is useful for highlighting choices that will need to be weighed in making assumptions to determine costs and for providing a sense of the scale of the likely total resources needed to implement high-quality early care and education in the United States.

The committee was also not tasked to undertake a full economic evaluation of the recommended financing system. Given our charge, the focus of our investigations is naturally on the cost of the transformed system, and the report gives less attention to quantifying the potential benefits. In effect, an underlying premise of the study’s charge is that further investment of public dollars in high-quality early care and education from birth to kindergarten

entry is socially beneficial. While a full economic evaluation of the cost and financial modeling is beyond this study’s scope, we briefly review the argument for public subsidies. We also point to some of the limitations of the current evidence base that undergirds the economic argument; see Box 1-2.

The scope of the committee’s charge also prohibited it from making recommendations regarding the balancing of entire federal, state, and local budgets. Though the committee recognizes that financing early care and education with a qualified workforce will require more funding than is currently in the system, we leave to elected officials the task of balancing budgets and making decisions regarding allocation of funds between, for example, health care and early care and education, or between the criminal justice system and early care and education. The committee does, however, discuss the implications of allocating costs between the local, state, and federal governments and the private sector, including families’ share of costs. We also identify and discuss options for raising revenue and the tradeoffs inherent in those options, recognizing that policy and political decisions will affect the feasibility of different options in different contexts.

In this report, the committee presents a vision for ECE financing that will provide reliable, accessible high-quality early care and education, including a well-qualified and adequately compensated workforce, for young children from birth to kindergarten entry and across settings that include home-based care, center-based care, and prekindergarten classrooms.

DEFINING EARLY CARE AND EDUCATION

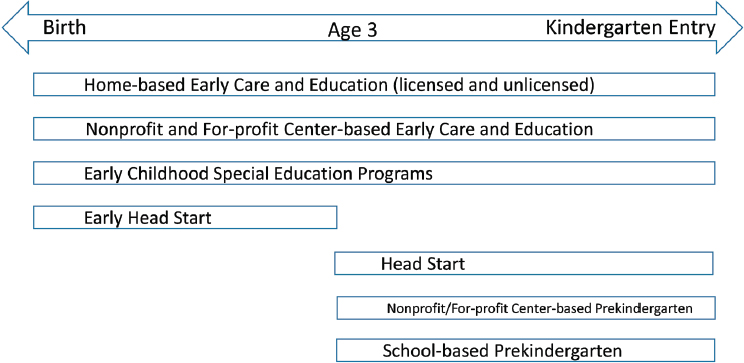

Early care and education can be defined as nonparental care for children from birth to kindergarten entry that occurs outside a child’s home. Because of this report’s focus on financing, the committee focuses on paid, nonparental care. Such early care and education occurs in a variety of settings including centers, homes, and schools. A particular ECE setting may offer services for all children from birth to kindergarten entry or may serve only children of particular ages, as shown in Figure 1-1. Services across these settings may be offered on a full-day or part-day basis.

ECE settings also vary by type: some are publicly funded (such as Early Head Start, Head Start, and state-funded prekindergarten), some are private, market-based centers or homes relying on parent fees (many of which are subsidized by federal block grants to the states), while many ECE settings rely on a mix of public and private funding. Publicly funded programs may be targeted to specific children, such as children from low-income families or children with special needs, while others may be universal (i.e., offered to all children in a specific jurisdiction regardless of income or other characteristics). Private ECE providers may be for-profit or nonprofit businesses and may be licensed, unlicensed, or license exempt.

SOURCE: Adapted from Institute of Medicine and National Research Council (2015, p. 44).

Taken together these ECE settings, programs, and services, in connection with the policies, regulations, and financing that shape their operation and the roles of and training for professionals in each setting, make up a “system” of early care and education. A “system” is defined by social scientists as an interrelated set of roles and expectations that tends to maintain itself over time (see, e.g., Parsons and Shils, 1965). The committee notes that, applying this definition, early care and education is a self-perpetuating system. As such, it is more difficult to reform than if there were truly “no system” (in the sense used by social scientists). The “financing structure” or “financing system” of early care and education is a subset of this broader ECE system and refers to the policies, regulations, funding streams, and financing mechanisms3 that shape the financing of early care and education in the United States. Therefore, like the Transforming report, the committee uses the term “system” to refer to both “complex wholes and specified subsets (such as ‘professional learning systems’)” (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2015, p. 28).

Of course, the ECE system is not the only influence on a child’s early learning and development prior to entering kindergarten. Professionals in the health and social services sectors, as well as parents, family, and

___________________

3 Financing mechanisms are the method by which funds are distributed to entities such as providers, families, or the workforce; see Chapter 3 for further discussion of financing mechanisms, specifically Box 3-1.

communities, interact with children and have the potential to support their early learning and positive development (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2015, p. 24). Because the Transforming report—and as a result, this committee’s charge—focuses upon early care and education as defined above, this report does not examine these other influences on young children. Interventions such as home visiting programs, prenatal programs, and parental education programs are discussed in another report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2016b): Parenting Matters: Supporting Parents of Children Ages 0-8. The findings of that report are briefly summarized in Box 1-3.

TRANSFORMING THE EARLY CARE AND EDUCATION WORKFORCE

According to the Transforming report, the science of child development and early learning underscores the importance and complexity of working with young children. That science elucidates the need for consistency and continuity in early care and education, both over time as children develop and across systems and services. Despite this need, the care and education of young children takes place in many different settings with different practitioner traditions and cultures and operates under the management or regulatory oversight of diverse agencies with varying policies, goals, incentives, funding requirements, and constraints (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2015, pp. 19–20, 30, 51). The roughly 2 million paid professionals that provide early care and education to children from birth to kindergarten entry in the United States work in disparate systems and delivery settings.

The relevant systems and services are diverse, fragmented, and often decentralized at a time when children would benefit most from high-quality experiences that build on each other consistently over time (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2015). Despite their shared objective of nurturing and securing the future success of young children, ECE professionals are neither acknowledged nor respected as a unified workforce; these professionals make a shared contribution to outcomes for young children and need a common knowledge base and consistent set of competencies to effectively perform their jobs. The Transforming report concluded that current policies and systems fall short of placing enough value on the knowledge and competencies required, and the expectations and conditions of ECE educators’ employment do not adequately and consistently reflect their significant and critical contribution (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2015, p. 483).

To address this shortfall, the Transforming report offered a blueprint to build a unifying foundation for workforce development. This foundation

encompasses: essential features of child development and early learning, shared knowledge and competencies for ECE professionals, principles for high-quality professional practice at both the individual level and the level of systems that support them, and principles for effective professional learning (i.e., the preparatory and continuing education of ECE professionals) (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2015, p. 40).

Professional learning and ECE workforce development need to complement each other and build together to lead to quality professional practice. These aspects include qualification requirements, higher-education program options (e.g., certificate programs as well as traditional postbaccalaureate degrees), professional learning during ongoing practice, and evaluation and assessment of professional practice. These elements are further influenced by two other important elements: interprofessional practice (how professionals with different roles interact) and well-informed, capable leadership. According to the Transforming report, implementing these recommendations will require coordinated and coherent changes across systems at three levels: individual practitioners and leaders, organizations, and policies. To that end, the report’s blueprint also included recommendations for coherent funding, policies, guidance, and standards; for supporting models of comprehensive planning and implementation; and for improving the knowledge base. Together these recommendations, if implemented, would align specific actions to improve workforce development and professional learning across localities, states, and nationally to ensure changes work in synchronicity (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2015, pp. 491–492).

While some specific aspects of the Transforming report’s recommendations are highlighted briefly in the sections that follow, readers of this report are strongly encouraged to read Chapter 12 of that report, which describes in depth the blueprint developed by that report’s authoring committee. It contains extensive discussion of context and considerations for implementation that are not duplicated in this report but that, taken together with this committee’s framework for financing, serve to inform both particular key decisions and any comprehensive planning process for improving the quality of early care and education.

Qualification Requirements

Expectations and requirements for preparation and credentials currently differ widely, depending on an ECE professional’s role, ages of children with whom he or she works, practice setting, purpose of service, and which agency or institution sets qualification criteria and funding requirements (Whitebook, McLean, and Austin, 2016). For example, one-quarter (26%) of center-based educators had a 4-year degree in 2013, while 16 to 19 percent of home-based educators had a bachelor’s degree or higher

(National Survey of Early Care and Education Project Team, 2013).4 Variation also occurs across ages within centers: only 19 percent of center-based educators of children ages 0 to 3 years had a bachelor’s degree, while 45 percent of center-based educators of children ages 3 to 5 years had a bachelor’s degree (National Survey of Early Care and Education Project Team, 2013, p. 3). In contrast, 93 percent of elementary and middle school educators in 2011 held a bachelor’s degree, and 48 percent of that degreed group also held a master’s degree (Whitebook, 2014). Similar variations exist in other forms of required and voluntary certifications and credentials for ECE professionals (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2015). These variations are often based more on historical traditions for different roles and settings or on what systems can afford, rather than on what the science of child development and early learning reveals about what children need in order to progress to their full potential. This variability can lead to substantial variations in knowledge and competencies and in the quality of professional practice in different settings (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2015, pp. 508–513).

Given these variations in professional qualifications and credentials, the Transforming report called for strengthening competency-based qualification requirements for all ECE professionals working with children from birth through age 8. These requirements, according to that report, should reflect foundational knowledge and competencies shared across professional roles, as well as specific and differentiated knowledge and competencies matched to the practice needs and expectations for specific roles (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2015, Recommendation 2, p. 513). Specifically, for lead educators5 working with young children, the report called for phased, multiyear pathways to transition to a minimum requirement of a bachelor’s degree with specialized knowledge and competencies and for strengthening of practice-based qualification requirements.

The relationship among an ECE professional’s level of education, high-quality professional practice, and outcomes for children is complex, as are the policy decisions around setting such qualification requirements. The authoring committee of the Transforming report found the empirical evidence about the effects of a bachelor’s degree on practitioner performance to be inconclusive and insufficiently informative. They concluded that a decision to maintain the status quo and a decision to transition to a higher level of education as a minimum requirement entail similar degrees of uncertainty,

___________________

4 Sixteen percent of educators working in listed home-based settings had a bachelor’s degree or higher, while 19 percent of educators working in unlisted home-based settings had a bachelor’s degree or higher.

5 The Transforming report defines “lead educators” as “those who bear primary responsibility for the instructional and other activities for children in formal care and education environments” (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2015, p. 513).

with near-equal potential consequence for outcomes for children. The committee therefore chose to recommend a transition to a minimum expectation of a bachelor’s degree with specialized knowledge and competencies on several grounds (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2015, pp. 513–521).

First, while a college education alone was not found to guarantee better instruction and improved child outcomes, according to the Transforming report, the quality of educators’ prior learning experiences in higher education and the extent of specialization in child development and early learning, including instructional practices did play an important role in enabling effective teaching and learning. Second, the differential that existed at that time (and continues now) in education requirements among early educators was inconsistent with the science of child development and early learning, which indicated clearly to the authoring committee that educating young children of all ages requires the same level of sophisticated knowledge and competencies. Finally, the Transforming report emphasized that holding lower educational expectations for ECE practitioners in general than for elementary school educators perpetuates the perception that educating children before kindergarten requires less expertise than educating early elementary students. Different degree requirements also affect the job market, both between elementary schools and early care and education and within early care and education, as a result of requirements for lead educators in Head Start and publicly funded prekindergarten programs to have a bachelor’s degree while lead educators working in center- or home-based settings generally do not have to meet the same requirements. The Transforming report committee saw this disparity in requirements perpetuating a cycle of disparity in the quality of learning experiences for young children (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2015, pp. 434–439). Moreover, public school educators from kindergarten to grade 12 are required to have, at a minimum, a bachelor’s degree, as well as certification, before they begin teaching (Whitebook, 2014).

For the reasons described above, the authoring committee of the Transforming report chose to recommend a transition to a minimum expectation of a bachelor’s degree with specialized knowledge and competencies. However, these requirements for higher levels of education and competencies, according to the Transforming Report, must be combined with fair compensation to recognize the professionalization of the workforce and to ensure workforce retention. Compensation of ECE professionals varies not only by program site but also by the age of children served. According to data from the National Survey of Early Care and Education, the median hourly wage for center-based practitioners working with children ages 0 to 3 was $9.30, while the median hourly wages of center-based practitioners working with children ages 3 to 5 was $11.90 (National Survey of Early

Care and Education Project Team, 2013, p. 12). At these low wages, nearly one-half of these professionals participate in public support programs, which is twice the fraction for the labor force at large (Whitebook, 2014). Without linking qualification requirements to compensation, more highly qualified ECE educators will seek higher paying jobs in other settings or with older children, making recruiting and retention of highly qualified professionals for younger children difficult (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2015, pp. 469, 471, 521).

The Transforming report also emphasized the need to combine fair compensation with other improved supports for ECE professionals in their practice environments, such as instructional supports (e.g., curricula, tools, and materials; mentoring and coaching; supervision); noncontact time for planning and assessments, supportive leadership, and opportunities for collegial sharing that foster ongoing professional learning; facilities and a physical environment conducive to learning; and linkages to interprofessional support to promote the ECE workforce’s professional development and mental and emotional well-being.

Higher Education and Ongoing Professional Learning

The Transforming report found a need for greater consistency in professional learning supports, both in higher education and during ongoing practice. It emphasized that simply instituting policies requiring a bachelor’s degree is not sufficient. The report recommended changes to improve the content and quality of higher-education programs that prepare educators to work with young children, as well as considerations to enable access to and affordability of those programs for both the future and incumbent workforce.

With respect to learning as a part of ongoing practice, the Transforming report concluded that there is great variability in the availability of and access to high-quality learning activities across professional roles and practice settings (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2015, p. 410). Therefore, it recommended strengthening incentives and systems to promote adoption and implementation of best practices for high-quality professional learning; it also offered guidance on sequencing. To affect practice, high-quality programs need to be widely available, accessible, and affordable as well as implemented in a practice environment that supports improvements and professional development. Such practice environments need to be structured to allow ECE professionals to proactively engage in quality improvement activities and should include time for reflection and planning and for sharing with colleagues (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2015, p. 533).

Evaluation and Assessment of Professional Practice

In addition, the Transforming report recommended developing new approaches for assessing the quality of professional practice for ECE professionals. According to that report, continuous quality improvement systems should align with the science of child development and learning, be comprehensive in scope, reflect day-to-day practice, be tied to access to professional learning, and account for setting- and community-level factors that affect the capacity of educators to practice effectively, such as insufficient non-childcare time for planning and assessment, overcrowded classrooms, and poorly resourced settings. The Transforming report also acknowledged the critical role of a supportive infrastructure for enacting good practice, and it recommended specific actions to bolster the supports that will make these changes to workforce development feasible, such as a well-informed and capable leadership; coherent policies, guidance, and standards; quality practice environments that support professional well-being; and a connection to the evolving knowledge base (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2015, pp. 534–536).

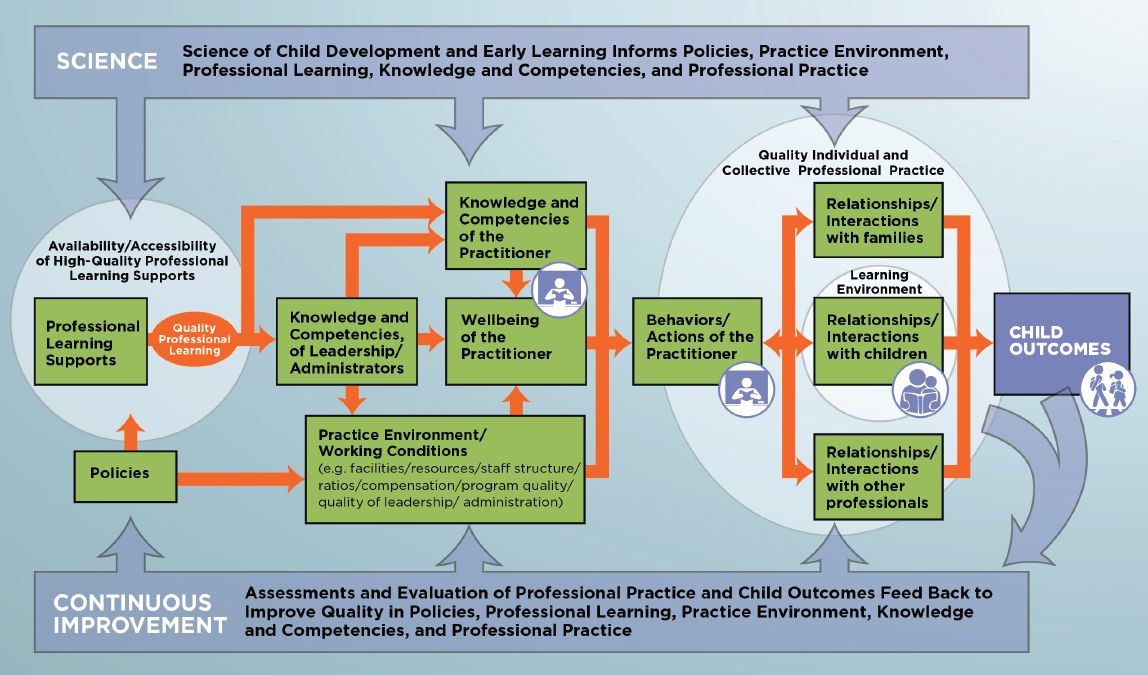

In summary, transforming the ECE workforce requires attention to various elements that contribute to quality professional practice, as illustrated in Figure 1-2. These elements of quality professional practice include the systems and processes that contribute directly to the development of knowledge and competencies for the ECE workforce, but they also extend beyond to encompass elements such as the practice environment, policies and regulations affecting professional requirements, staffing structures and career advancement pathways, evaluation systems, and the status and well-being of these professionals. As the Transforming report made clear, ensuring that the ECE workforce is highly qualified and well supported is integral to supporting the positive childhood development of all children.

Implementing Transformative Change

The Transforming report emphasized the challenges of the complex, long-term systems change required to implement its recommendations, and it acknowledged the uncertainties within each of the areas for which recommendations were made and around how best to design, prioritize, and phase in the interdependent changes. Acting on that report’s blueprint (see Chapter 12 of the Transforming report) requires context-specific policy and political decisions. Full implementation in some cases could take years or even decades. At the same time, the report emphasized the urgency of the need to improve the quality, continuity, and consistency of professional practice for children from birth through age 8 (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2015, p. 5).

SOURCE: Institute of Medicine and National Research Council (2015, p. 359).

In articulating some of the considerations to balance the reality of the challenges with the urgency of need, the report called for strategic prioritization of immediate actions as well as long-term goals with clearly articulated intermediate steps. Further, the report made recommendations to support that process with coherent policies, guidance, and standards, to support and learn from models of comprehensive planning and implementation, and to improve the knowledge base through monitoring, evaluation, and research as changes are made to transform the ECE workforce (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2015, p. 492).

The steps needed will depend on factors that are specific to the context of different state and local environments, which will have different strengths and gaps at the outset, in addition to different population characteristics, infrastructure for professional learning, and labor markets, all of which affect both the current workforce and the pipeline for the potential future workforce. The specific approach and pace of progress will thus depend on the baseline status, existing infrastructure, and political will in different localities (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2015, p. 492).

The Transforming report also recognized that significant mobilization of resources will be required, that the amount and sources of financial and other resources vary in different contexts, and that information about costs are a key input to policy and political decisions. However, the committee authoring the Transforming report was charged, in approaching its task, to set aside questions of cost and financing to avoid foregone conclusions about the availability of resources in interpreting the evidence and the current state of the field (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2015, p. 492). It is now the charge of this committee to pick up this critical piece of the puzzle.

FINANCING HIGH-QUALITY EARLY CARE AND EDUCATION

A wide range of resources contribute to supporting the health, well-being, development, and learning of children from birth to kindergarten entry. Federal funds, as well as state and local funds, support child development and early learning. In addition, funds invested in children come from nongovernmental sources including philanthropy and the business sector. However, families’ share of ECE costs contributes the largest portion of the total cost for early care and education. Funds supporting early care and education from other sources are distributed to service delivery providers, families, and the ECE workforce through a number of financing mechanisms, such as tax preferences, vouchers, and contracts or grants.

This patchwork of financing with different funding sources and financing mechanisms leads to inequities in access, quality, affordability, and accountability. Each funding source and financing mechanism is subject to the policies of the agency or institution from which it derives, and “each has its own requirements as to scope of services allowed, quality standards (or lack thereof), eligibility criteria (including ages served), and reporting and accountability” (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2015, p. 51). This fragmentation, coupled with underfunding of services, results in uneven quality and access to services and places the burden for financing early care and education on parents through the family’s share of costs and on the ECE workforce in the form of low wages. In addition, the current piecemeal approach to financing results in inefficiencies in administration; difficulty in collecting, across various programs, the data needed for system improvement; and an inability to attract and retain a highly qualified workforce (see Chapters 2 and 3 of this report.) The resulting inequities in access to affordable high-quality early care and education drive and perpetuate socioeconomic and racial/ethnic inequalities in the United States.

Drawing from the Transforming report and the science of child development and early learning, this committee has extracted six principles for high-quality early care and education and from these principles developed a set of criteria by which to judge the current financing structure. These six principles, presented in Box 1-4, and the criteria developed from them (see Chapter 3) guided the committee’s assessment of financing strategies for promoting implementation of and access to affordable, high-quality early care and education for children from birth to kindergarten entry. The rationale for each principle is presented below.

First, high-quality early care and education requires a diverse, competent, effective, well-compensated, and professionally supported workforce across the various roles of ECE professionals. High-quality care for children rests upon the knowledge, skills, well-being, and stability of the ECE workforce. According to the Transforming report, “Adults who are under-informed, underprepared, or subject to chronic stress themselves may contribute to children’s experiences of adversity and stress and undermine their development and learning” (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2015, p. 4). That is, this workforce needs the competencies and compensation commensurate with the responsibility of caring for and guiding the development of young children. It also requires adequate supports to ensure that all ECE professionals are able to perform their duties at a high level, to foster the positive development of children in their care. However, across and within states, the current qualification requirements for regulated home-based and center-based ECE programs and public prekindergarten educators vary. For example, only 11 states set consistent entry-level requirements across licensed settings, and qualifications set by the

federal government for federally funded programs add further complexity to the array of requirements in a given community (Whitebook, McLean, and Austin, 2016). As a result, the qualification requirements for an ECE professional depend upon the funding source for the program in which he or she is employed, rather than the developmental needs of the children under care (Gould, Austin, and Whitebook, 2017; Whitebook, McLean, and Austin, 2016).

Because of traditionally low-qualification requirements, the ECE field has generally been perceived as low-skilled work, which contributes to low wages for this workforce. ECE professionals are among the country’s lowest-paid workers and typically do not receive benefits such as health insurance.6 In the current system, the median hourly wage for center-based ECE practitioners is $10.60. If employed full time, that amounts to about $22,000 per year, which is just slightly above the federal poverty level for a family of three. Even center-based practitioners who have a bachelor’s degree or higher are paid at significantly lower levels than other professionals with a similar level of education, garnering a median hourly wage of

___________________

6 See Bureau of Labor Statistics, Occupational Employment Statistics, Occupational Employment and Wages, May 2016 data on “child care worker” and “preschool teacher.” Available: https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes399011.htm; https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes252011.htm [December 2017].

only $14.70 (National Survey of Early Care and Education Project Team, 2013, p. 12).

Moreover, compensation varies among ECE practitioners working in different types of settings, with different age groups of children, and with different funding sources. Across ECE centers, for example, the median wage for practitioners with a high school degree or less ranges from a low of $8 per hour to a high of $11.80 per hour, depending on whether the center received any public financing and of what type. Across all educational attainment levels, median wages are highest—from one-third to almost 50 percent higher than other settings—in public school–sponsored ECE programs (Dastur et al., 2017).

These low wages are largely the result of an inadequately financed system where the cost burden falls on families and the ECE workforce. Together, low wages and wage variation within the ECE workforce contribute to stress among staff, relatively high job turnover rates, and instability in the workforce, all of which can decrease the quality and increase the cost of programs. For example, high staff turnover affects continuity of care for children, inhibits quality improvement, disrupts attachment between children and practitioners, and increases program costs (Whitebook, Phillips, and Howes, 2014). Therefore, adequate compensation results in a more stable, economically secure workforce, which benefits all children (Bueno, Darling-Hammond, and Gonzales, 2010; Whitebook, Phillips, and Howes, 2014).

Moreover, though the increasing diversity of the child population requires educators to be knowledgeable and skilled in meeting the needs of children from a range of cultural and linguistic backgrounds, the current ECE workforce tends to be stratified racially and ethnically by role and educational attainment (Whitebook, 2014; Whitebook, McLean, and Austin, 2016, p. 31). This stratification is partially the result of a financing structure that is inadequate to support the incumbent workforce’s professional development and attainment of the higher qualifications necessary to take on leadership roles.

Our second principle is that high-quality early care and education requires that all children and families have equitable access to affordable services, across all ethnic, racial, socioeconomic, and ability statuses as well as across geographic regions. Disparate access to high-quality early care and education contributes to achievement gaps between children from low- and high-income families. Disparities by income in terms of cognitive skills, health, and behavior have been found as early as 9 months of age, and children from low-income families are, on average, 12 to 14 months behind their higher-income peers in pre-literacy and language skills when they start kindergarten (Fernald, Marchman, and Weisleder, 2013; Halle et al., 2009; National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2000; Yoshikawa et al., 2013).

The inability of families to access high-quality early care and education stems from a financing structure that places a large burden to pay for early care and education directly on families in the form of fees and tuition, making high-quality early care and education prohibitively expensive for many families with low income. Average weekly expenditures for all children, ages 0 to 5 years, among households that pay for early care and education is slightly more than $130 per week, but one-quarter of families using either paid home-based care or center-based care paid more than $180 per week (Latham, 2017; see also Loewenberg, 2017).7 In 30 states and the District of Columbia, the average yearly cost for an infant in full-time center-based care exceeds the cost of a year’s tuition and fees at a 4-year public university (Child Care Aware of America, 2016). As a whole, families pay 52 percent of the cost of early care and education in the United States, making it the only part of this country’s education pathway in which parents shoulder the majority of the financial burden (BUILD Initiative, 2017). Even for those families that qualify for subsidized programs, many are not receiving assistance because the ECE system is underfunded. Only about one-sixth of children eligible for subsidized early care and education receive it (Burgess et al., 2017).

The current financing structure positions a child’s early learning and development as dependent upon that family’s socioeconomic status and geography, rather than basing it on the child’s developmental and learning needs. This structure weakens the potential of early care and education to spur positive childhood development and enhance adult-life outcomes.

Our third principle states that high-quality early care and education requires financing that is adequate, equitable, and sustainable, with incentives for quality. Moreover, it requires financing that is efficient, easy to navigate, easy to administer, and transparent. As described above, the current financing structure is underfunded, placing a heavy cost burden on families and the ECE workforce. In addition, the cost burden on families is not equitable in the sense that the lowest-earning households contribute a higher percentage of their income to ECE costs than do higher-income families. (Chapter 2 addresses this issue in detail, see Table 2-4 in particular.) While most families in poverty do not make payments for early care and education, some families in poverty spend more than one-third of their income on it, and those with incomes at one to two times the federal poverty line spend about one-fifth of their income on early care and education (Latham, 2017). Even middle-income families may be priced out of the center-based ECE market at current costs, as the data suggest that middle-income families use relatively less center-based, and more home-based, early care and education

___________________

7 The average price for full-time care in child care centers for children, ages 0 to 4 years, is $9,589 a year (Loewenberg, 2017).

than do either low-income families (who are likely to receive assistance) or upper-income families (who have greater discretionary income) (Latham, 2017). Again, the current financing structure forces many families to choose an ECE option based upon their budget, rather than their children’s developmental needs. The ECE financing structure also affects quality; as documented in detail in Chapter 3, the current financing mechanisms are insufficient to promote high-quality early care and education.

Moreover, public programs meant to assist families in finding and affording high-quality early care and education are often disconnected from one another. Families are left navigating among these complex and often confusing systems. For example, the various financing mechanisms supporting early care and education have eligibility requirements that vary between programs, which can result in ECE instability when a family’s circumstances change. This scattershot approach to ECE financing makes it enormously difficult for families to negotiate the complex eligibility criteria, find and access ECE programs, and afford their share of the cost. Furthermore, most providers receive funding through multiple financing mechanisms, each with its own standards and requirements. As a result of this piecemeal approach to ECE financing, providers bear the administrative burden of combining and coordinating across funding sources.

Our fourth principle is that high-quality early care and education requires a variety of high-quality service delivery options that are financially sustainable. Families have diverse needs: some need care for their children during standard business hours, others need care during the evening or weekend hours, while still other families may prefer to enroll their children in home-based care settings or center-based care. A financing structure that allows and supports access to a diversity of service delivery options for all families is required to meet these diverse needs.

Our fifth principle states that high-quality early care and education requires adequate financing of high-quality facilities. The Transforming report outlined the relationship between high-quality ECE facilities and the intellectual and psychosocial development of young children. A well-designed learning environment can promote exploratory learning and physical activity, facilitate positive interactions, and keep children safe and healthy. For example, well-designed facilities with semiprivate reading areas encourage one-on-one interactions between educators and young children that are necessary for building healthy relationships with adults (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2015). Children further benefit from both indoor and outdoor spaces with age-appropriate materials that are engaging and promote social and intellectual development (Workman and Ullrich, 2017). Other scholars have suggested that appropriately designed spaces facilitate creative play and minimize conflicts among children, and

outdoor play is associated with reduced stress and obesity levels in young children, as well as stronger immune systems (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016; Fjortoft, 2004; Gillman, Raynor, and Young, 2011; Mead, 2016; Pardee, 2011). These studies demonstrate the importance of facilities in creating high-quality environments and promoting children’s health, safety, and development.

The committee’s sixth and final principle states that high-quality early care and education requires systems for ongoing accountability, including learning from feedback, evaluation, and continuous improvement. As discussed in the Transforming report, accountability systems employing several data sources can be used to improve instructional practices, the delivery of services, ECE programs, and ongoing professional learning, as well as to inform the efficient allocation of financial resources (Kauerz and Coffman, 2013; Tout et al., 2013). If properly aligned, accountability systems can thus influence child development by enhancing the ability of ECE professionals to foster greater consistency and continuity for children and families throughout the continuum from birth to kindergarten entry. However, there is currently no comprehensive data system that collects data from the wide variety of ECE programs and providers, nor is there any comprehensive accountability system for tracking and incentivizing quality. Decision makers who design accountability systems must make a complex set of decisions about which programs will be held accountable, how quality will be measured, how improvement will be incentivized and supported, and how to share information with parents in a way that will help them find high-quality learning opportunities for their children. Often these critical design issues are decided on “best guesses,” and because of the current financing structure, they are commonly constrained by limited financial resources.

Applied together, these six principles constitute the committee’s understanding of what high quality means in early care and education; they have informed our development of a new vision for a financing structure that can provide reliable, accessible, and affordable high-quality early care and education, provided by a well-qualified workforce, for all of the nation’s young children from birth to kindergarten entry.

STUDY METHODS

To understand the current landscape of financing for early care and education in the United States, the committee reviewed multiple sources of information. Our assessment focused primarily on the existing research literature in disciplines, such as early care and education, financing and fiscal management, economics and labor economics, and public policy. The

committee reviewed public documents, such as federal appropriations legislation and state and local governments’ budgets, as well as recent reports and articles on the state of early care and education in the United States. As outlined in its charge, the committee also reviewed and analyzed ECE financing structures in other countries. Our review included an analysis of each country’s funding structure, including financing mechanisms, funding levels, and cost distributions, as well as regulations and local labor market variations that may influence costs. Of course, early care and education in every country is deeply contextual and reflects the local, political, and cultural/religious traditions of that society, as it does here in the United States. Some countries have well-established, high-quality systems, while others have only recently initiated efforts to transform their systems to achieve high quality. Some countries, like the United States, have market-based systems, but other countries use a publicly financed system; countries organize these systems in different ways with regard to the age range of children covered by the system and the concept of early care and education that informs the system. These context-specific characteristics were vital for drawing valid lessons from these international examples, as the committee grappled with the feasibility of adopting various approaches in the United States.

The committee held four in-person meetings and conducted additional deliberations by teleconference and electronic communications during the course of the study. The first and third in-person meetings were information-gathering meetings during which the committee heard presentations from a variety of stakeholders, including the study’s sponsors, representatives from federal and state governments, employers supporting high-quality early care and education, researchers, and policy advocates. The committee also heard from experts in the housing, higher education, and health care fields regarding affordability and distributions of costs in other sectors, as well as an expert on international early care and education. The second and final meetings were closed to the public in order for the committee to deliberate on our report and finalize our conclusions and recommendations.

Consistent with the complexity and uncertainty inherent in making significant policy and systems changes, and especially given the large amount of resources under consideration, various committee members held a range of views on which changes within the blueprint provided by the Transforming report have the strongest case for prioritizing investment, on the needed sequencing and pace of the recommended changes, and on the best ways to approach the financing of those changes. Given that revisiting the Transforming report’s recommendations were outside this committee’s charge (see the section above on the “Charge to the Committee”), the committee discussed how to finance the changes recommended in the Transforming report and the relative potential benefits and negative consequences

of assuming different priorities in financing high-quality early care and education, especially for changes that are large cost drivers, such as implementing degree requirements for lead educators, the level of appropriate compensation for ECE professionals, and whether early care and education with no fees should be available to families. All of these alternatives have both independent and interdependent implications for costs of the end-state system and costs of the interim stages toward achieving it.

These discussions highlighted the importance of acknowledging that as local communities and states experiment and diligently work on improving early care and education, the vision that informed the recommendations from the Transforming report and provided a starting point for this report will need to be adjusted to find how, in a given context, to move most rapidly and efficiently to a system that meets the needs of children, families, and the ECE workforce. Our final report represents the consensus of the committee, and its framework of options and tradeoffs that need to be considered captures the richness of the range of views and discourse that emerged through the committee process.

ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT

The committee’s report on financing early care and education has been organized into seven chapters. Following this introduction, Chapter 2 describes the landscape of the current financing system and estimates the total funds currently invested in early care and education in the United States. Chapters 3, 4, and 5 analyze the current financing of early care and education using the principles described above. Chapter 3 focuses on financing a highly qualified workforce, Chapter 4 focuses on financing for early care and education that is accessible and affordable for all families, and Chapter 5 assesses financing for incentivizing quality. Chapter 6 reviews the cost drivers of high-quality early care and education and uses a hypothetical estimate of the costs of a high-quality ECE system to illustrate the factors that inform options and the choices that are likely to require decision. That chapter also summarizes the relevant considerations necessary to produce such a cost estimation for a real-world option. Chapter 7 builds upon lessons learned from states and localities, from international early care and education, and from sectors other than early care and education, in order to make recommendations for a new future in financing early care and education in the United States.

In addition to the main chapters, the first three of four appendixes supply background information important for this study. Appendix A provides an explanation of the policy choices and assumptions, necessary to estimate onsite cost, that form the basis for the committee’s illustrative estimate of

the total cost of a high-quality ECE system. Different policy choices and assumptions would, of course, lead to changes in the estimate, so this appendix is important for moving beyond the example to real-world options and decisions. Appendix B presents key attributes and considerations for desirable outputs of cost models, in addition to a description of various cost models that are currently available. Appendix C discusses methods to determine a reasonable share of costs for families to pay for high-quality early care and education. Appendix D provides biographical sketches of the committee’s members and staff.