7

A Vision for Financing Early Care and Education

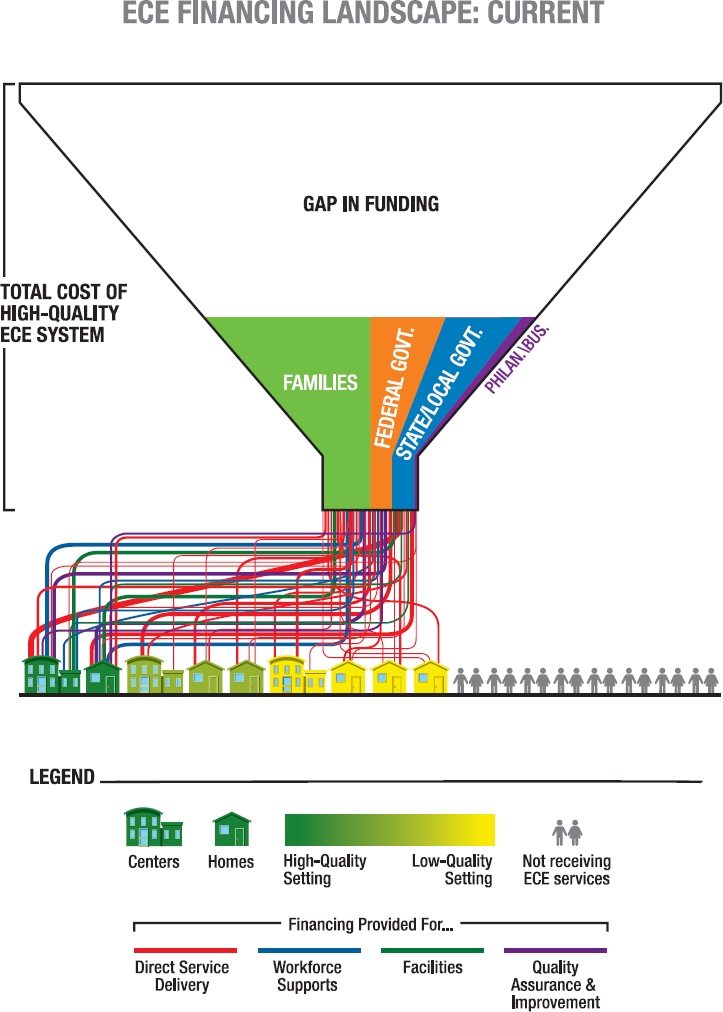

Investments in high-quality early care and education for children from birth to kindergarten entry are critical to positive child development and early learning. These investments benefit not only children and their families but also society at large. Unfortunately, only a small share of children currently have access to such high-quality programs because the cost of providing access to affordable, high-quality early care and education for all children far exceeds current funding amounts. The majority of children in families choosing to use early care and education (ECE) services are in low- or mediocre-quality programs that do not have the resources necessary to support the emergence of the developmental and economic benefits that are possible (Bassok et al., 2016; Burchinal et al., 2010; Valentino, 2017). There are also a substantial number of children whose families wish to participate in early care and education but are unable to use any early care and education because of a lack of either available ECE services or family resources to pay for placement in the available settings. (Figure 7-1 represents these realities of the current system.) Given what science shows regarding the benefits of quality early learning experiences for positive childhood development and a lack of systemic progress to improve the quality of early care and education offered in the United States,1 an effective financing structure is needed to address these persistent problems. This chapter offers a number of recommendations to develop an effective financing structure for a high-quality ECE system in the United States for all children from birth to kindergarten entry. Several central concepts

___________________

1Institute of Medicine and National Research Council (2015).

underlying these recommendations have the potential to transform the current state and provide affordable access to high-quality ECE options for all children and families.

The committee envisions a transformed, effective ECE financing structure that builds on the six principles we presented in Chapter 1 (see Box 1-4):

- High-quality early care and education requires a diverse, competent, effective, well-compensated, and professionally supported workforce across the various roles of ECE professionals.

- High-quality early care and education requires that all children and families have equitable access to affordable services across all ethnic, racial, socioeconomic, and ability statuses as well as across geographic regions.

- High-quality early care and education requires financing that is adequate, equitable, and sustainable, with incentives for quality. Moreover, it requires financing that is efficient, easy to navigate, easy to administer, and transparent.

- High-quality early care and education requires a variety of high-quality service delivery options that are financially sustainable.

- High-quality early care and education requires adequate financing for high-quality facilities.

- High-quality early care and education requires systems for ongoing accountability, including learning from feedback, evaluation, and continuous improvement.

In the envisioned transformed and effective financing structure, an integrated system of laws and policies will ensure that each of the following goals is attained:

- Financial support for early care and education will be based on covering the total cost of high-quality early care and education (i.e., the costs of service delivery with a highly qualified and adequately compensated workforce and system-level supports, including mechanisms for accountability and improvement) and will hinge on a consistent set of quality standards applied across a mixed delivery system.

- All ECE providers meeting high quality-standards will have access to a core amount of institutional support based on the cost of recruiting, retaining, and professionally supporting a well-qualified workforce and meeting the developmental needs of all children.

- Families from all socioeconomic, racial, ethnic, and geographic backgrounds who choose ECE programs will pay either no fee or

-

an amount they can reasonably afford, with a systemwide harmonized combination of assistance mechanisms that do not leave gaps for any income groups and that are easy to navigate.

- Ongoing investments are made in an infrastructure for support and accountability in attaining quality goals, ensuring access, and spending funds effectively.

- Public funding is substantially increased, phased in over a transition period, to enable transformation and the building of an adequate, equitable, and sustainable system.

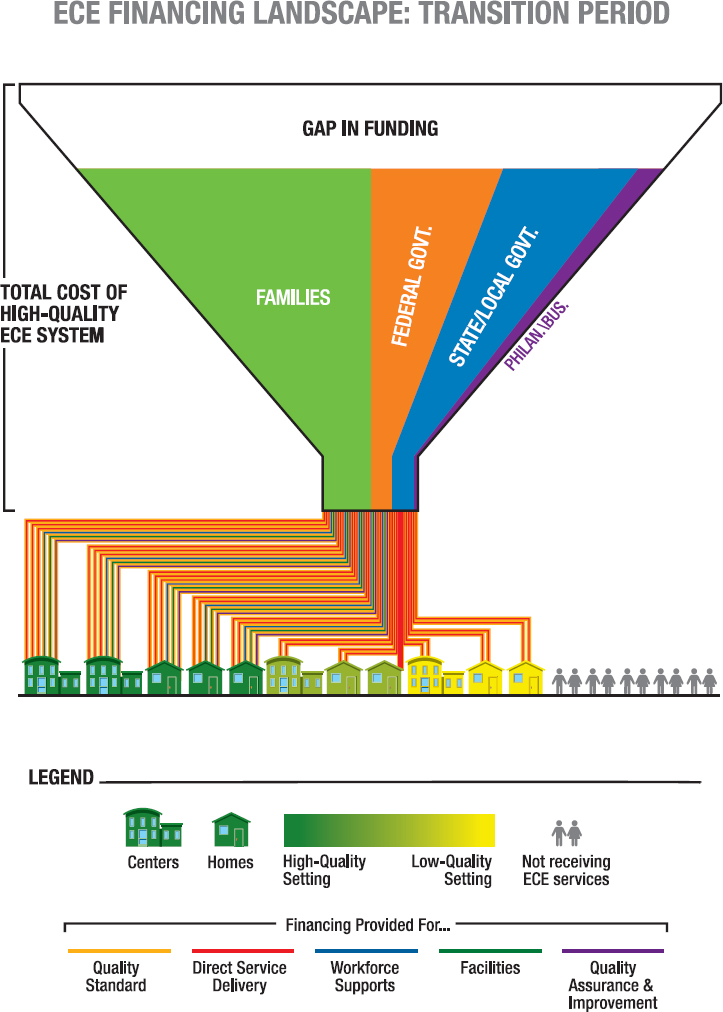

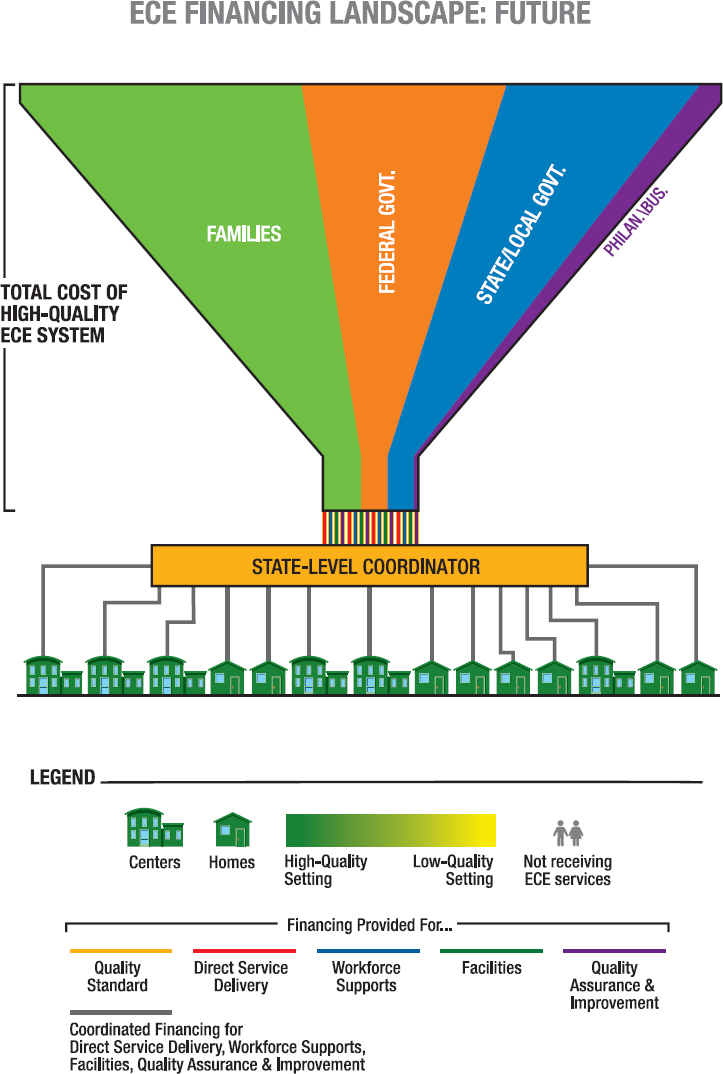

Full implementation will require a transition period; Figure 7-2 represents the ECE landscape during this transition period. Full implementation also will require ample political will and political leadership to shepherd necessary changes at the federal, state, and local levels.2 At the same time, there is great urgency to begin to work on realizing this vision immediately. (Figure 7-3 shows the high-quality ECE system envisioned in this report.) Many components of the ECE structure in the United States are currently inadequate—for parents, for children, and for the ECE workforce. While all children and families stand to benefit from a coordinated, high-quality ECE system that is accessible and affordable, the consequences of the current approach to financing have left many families without access to affordable, high-quality early care and education, a situation that perpetuates and drives inequality.

AN EFFECTIVE FINANCING STRUCTURE

The previous chapters make clear that the current structure for ECE financing is fragmented and inconsistent. Current financing mechanisms tend to treat each part of early care and education—service delivery, system supports, and workforce supports—as a separate area, rather than as parts of an integrated system with interdependent components. These financing

___________________

2 In this chapter, when the committee recommends that federal, state, or local governments take action, we are recommending that all relevant agencies at each level of government participate in such actions. At the federal level, relevant agencies include those with programs that have an explicit ECE purpose (Department of Defense, Department of Education, Department of Health and Human Services, Department of the Interior), those that have programs that permit use of funds for ECE purposes (Department of Agriculture, Department of Education, Department of Health and Human Services, Department of the Interior, Department of Justice, Department of Labor, and the General Services Administration), and those that manage tax expenditures that support early care and education (Department of the Treasury) (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2017). In order to realize the committee’s coordinated vision of a cohesive ECE system, changes will need to occur across agencies and the existing silos between agencies, which are rooted in historical supports for either child development or work/welfare goals of early care and education, will need to be dismantled.

mechanisms often do not adequately promote or incentivize high-quality ECE options. Moreover, public programs to assist families in finding and affording high-quality early care and education are either disconnected from one another, leaving families to navigate between complex and disparate systems, or not adequately funded, leaving eligible children without access to ECE services. The disjointed structure also places a heavy administrative burden on providers and is inadequate to reward and professionally support the nearly 2 million ECE professionals entrusted with the care and education of young children. The lack of a cohesive system of high-quality, affordable early care and education therefore represents significant missed opportunities: for children’s positive development and school readiness, for families’ workforce readiness, for creating viable employment for more than 2 million people in the ECE workforce, and for developing the nation’s future workforce.

To realize the considerable potential benefits of early education, an integrated framework of laws and policies is needed, in which financing is used to bring about an accessible, affordable, and high-quality system for all children from birth to kindergarten entry. Such a financing structure should include adequate and coordinated funding for service delivery that allows for not only a professionally supported workforce but also system-level supports for workforce development and quality assurance, including mechanisms for accountability and improvement. This structure should facilitate the integration of funds from federal ECE programs (including but not limited to the Child Care and Development Fund [CCDF] and Head Start) and state and local ECE programs (including but not limited to state-funded prekindergarten programs). The financing structure should provide flexibility to reduce silos and facilitate nimble and efficient coordination of revenue streams, standards, and requirements from disparate sources. This section discusses the key aspects of the financing structure: consistent, high quality-standards and cost-based payments; elimination of parental employment contingencies; harmonization of financing mechanisms to ensure access; and state-level coordination.

Consistent High Quality-Standards and Cost-Based Payments

Recommendation 1: Federal and state governments should establish consistent standards for high quality across all ECE programs. Receipt of funding should be linked to attaining and maintaining these quality standards. State and federal financing mechanisms should ensure that providers receive payments that are sufficient to cover the total cost of high-quality early care and education.

For the transformed financing structure to support the full cost of high-quality early care and education, all financing mechanisms need to use consistent, high quality-standards as the basis for receipt of funds through cost-based payments. Quality standards—where they even exist—currently vary across states and programs (Burchinal et al., 2010; see also Chapter 3). Providers find the complexity and cost of compliance obligations to multiple funders burdensome because they currently must meet the requirements of many authorities to generate enough revenue to support the costs of even the most basic services. In addition, because each financing mechanism has its own set of regulatory standards or monitoring requirements, standards are not coordinated and sometimes even conflict, resulting in confusion and inefficiencies.

To ensure equitable access to high-quality early care and education for all children, the federal government and the states should use consistent, high quality-standards across all public financing; that is, all financing mechanisms (provider-oriented and family-oriented) should be directly linked to standards consistent with the Transforming report (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2015). Such standards would include requirements for services delivered to children, staff qualifications and compensation, professional development, coaching and mentoring, and quality monitoring and assurance. In addition, federal and state standards should allow for a mixed delivery system that can include a variety of developmental and pedagogical approaches. Box 7-1 describes Washington state’s implementation of consistent base standards across its ECE programs.

The federal government should specify consistent, high quality-standards for all its financing mechanisms in consultation with the states, and any funding it provides should be linked to meeting those standards. Any state or local funding supporting those federal programs should also be linked to the same standards. In this way, the federal funding would act as a policy lever to induce high-quality early care and education with a highly qualified workforce at the state level. Individual states should also set consistent, high quality-standards across any financing mechanisms for which they are the primary funders, including any ECE mechanisms that the state is funding out of consolidated funding streams, which may include funds from the federal government. States should use the same standards across all financing mechanisms within the state and should not set different standards for state and federally funded mechanisms. In this way, states may exceed federal standards, but all programs in a state should be required to meet the same high quality-standards regardless of funding source.

These consistent, high quality-standards should be paired with accompanying financing mechanisms at levels adequate to attain and maintain quality (see discussion below on federal funding levels). Current federal

guidelines for ECE subsidies, for example, require consideration of market prices when setting state reimbursement levels. Market prices, however, do not reflect the costs of providing high-quality ECE, and states mostly do not set rates at a high enough percentile of market prices to cover the cost of quality, including recruiting and retaining a highly qualified workforce. A quality-oriented approach requires changing the basis on which reimbursement rates are determined so that rates reflect the total cost in each state or locality of high-quality early care and education, including the costs of service delivery with a highly qualified and adequately compensated workforce and system-level supports, including mechanisms for accountability and improvement.3 Such costs should also reflect the differential costs of serving children with different physical, emotional, and linguistic needs, especially the different staff qualifications, training, and structure required to meet those needs.4 Pegging reimbursement rates to the cost of delivering high-quality ECE services will increase stability and viability of providers and allow investments in quality improvements and the ECE workforce.

Ensuring Access to High-Quality Early Care and Education for All Children

The previous chapters identified four major limitations of the current financing mechanisms: they fail to serve many low-income families eligible for assistance, they fail to make high-quality early care and education affordable for other low- and middle- income families; the major family-oriented mechanisms (ECE assistance programs and tax preferences) are contingent on parental employment rather than the needs of children; and the shares of income that families across income groups pay in fees are regressive. This section addresses the need to eliminate parental employment requirements and the need for a harmonized set of mechanisms to

___________________

3 Compensation of qualified ECE staff is the main driver of high quality. Because staff costs and wages vary considerably across states and even by geographic region within a state, the dollar value of reimbursement rates would continue to vary across states and possibly by geographic regions within a state.

4 In some cases, creating supports for a child with a disability only requires staff knowledge and receptivity. Other instances may entail costs such as specialized equipment and facility improvements. Personnel supports may range from a specialized master’s-level professional to a one-on-one aide. A joint statement of the Division for Early Childhood and the National Association for the Education of Young Children on early childhood inclusion notes, “Specialized services and therapies must be implemented in a coordinated fashion and integrated with general early care and education services. Blended early childhood education/early childhood special education programs offer one example of how this might be achieved. Funding policies should promote the pooling of resources and the use of incentives to increase access to high quality inclusive opportunities” (Division for Early Childhood and National Association for the Education of Young Children, 2009, pp. 2-3).

avoid ECE utilization and affordability gaps; the need for greater public investments to ensure all eligible children can participate in early care and education is discussed in a subsequent section. Though the committee believes its recommendations will improve access and affordability of early care and education for all families, we note that greater access to mediocre- or low-quality care will not result in the desired developmental outcomes for children. While there may be a tension between improving access and improving quality if funding is insufficient or distributed through poorly designed financing mechanisms, the committee stresses that quality and access go hand-in-hand. In order to realize the potential for positive child development and early learning outcomes possible with early care and education, improved and equitable access to high-quality early care and education is needed.

Recommendation 2: All children and families should have access to affordable, high-quality early care and education. ECE access should not be contingent on the characteristics of their parents, such as family income or work status.

The committee expands on this recommendation with three corollaries that we view as essential to fulfilling the intent of the general recommendation:

2a. ECE programs and financing mechanisms (with the exception of employer-based programs) should not set eligibility standards that require parental employment, job training, education, or other activities.

2b. Federal and state governments should set uniform family payment standards that increase progressively across income groups and are applied if the ECE program requires a family contribution (payment).

2c. The share of total ECE system costs that are not covered by family payments should be covered by a combination of institutional support to providers who meet quality standards and assistance directly to families that is based on uniform income eligibility standards.

Eliminating Parental Employment Contingencies

While federal Head Start and state and local school-based prekindergarten programs either consider all children who meet age and family income

standards eligible for their services or are universally offered (though they do not serve all who are eligible), federal ECE assistance programs and tax preferences are only available to children with parents who are either employed or participating in approved education and training activities. Thus, the current financing structure positions a child’s early learning and development as dependent upon a parent’s employment status, rather than basing it on the child’s developmental and learning needs. This structure reduces access to needed financial support for some families, increases instability in ECE arrangements, and weakens the potential of early care and education to spur positive childhood development and enhance adult-life outcomes for all children. Family circumstances other than employment can make participation in ECE services desirable for children and their families, including enabling children to engage socially with their peers, improving school readiness through structured early learning, or supporting parents who care for other family members, among others (see Chapter 4). Affluent parents who are not employed are purchasing center-based early care and education for their children because they understand these advantages (see Chapter 4). Denying early care and education to children whose lower-income parents are not employed thus increases developmental gaps and inequities at the earliest ages. Given the need to ensure that every child has access to high-quality early care and education regardless of that child’s families’ circumstances, family-oriented financing should not be tied to requirements for parental employment or other activities (with the exception of employer-based programs).5

Eliminating the employment requirement for family-oriented assistance does not eliminate the promotion and encouragement of employment, rather it eliminates an unnecessary requirement that restricts access to ECE financial support only to children whose parents meet certain eligibility requirements including employment. Being able to access ECE services allows parents with young children to be employed, as research clearly demonstrates that reducing the cost of early care and education increases parental employment (see, e.g., Blau and Kahn, 2013) and that ECE access can be coordinated with access to services for training, education, and job placement, as exemplified in many two-generation approaches such as Head Start.6

___________________

5 However, divorcing family-oriented financing from an employment requirement does not prevent states from having the flexibility to provide assistance to families to purchase regulation-exempt ECE services under some circumstances. This flexibility may be required for states to meet the needs of families who require additional care related to their work, such as overnight care for shift workers. In this way, assistance could still be given to families with unique needs.

6 “Two-generation approaches focus on creating opportunities for and addressing needs of both children and the adults in their lives together.” See http://ascend.aspeninstitute.org/two-generation/what-is-2gen/ [December 2017].

A Harmonized Set of Financing Mechanisms

A harmonized combination of provider-oriented and family-oriented financing mechanisms should be available to all families and to all center- and home-based providers that meet quality standards. That is, financing mechanisms should be designed to jointly cover the full costs of high-quality early care and education and eliminate gaps in family eligibility for assistance, which discourage and prevent participation. A harmonized set of financing mechanisms would benefit all ECE providers by creating financial stability and enabling investment in the ECE workforce; it would benefit all families by allowing them to select among providers that meet their needs and preferences without having to lose the opportunity for a high-quality experience for their children.

Institutional support for providers through provider-oriented mechanisms would give qualifying centers and home-based providers the financial stability and ensured resources they need to invest in high-quality ECE offerings. Such support should be set at a proportion of total costs for planned enrollment but also at a high enough level to provide an ample base for investment in the workforce. Institutional support would be conditional on the provider agreeing to meet or exceed the quality standards set for the provider’s state or region, including standards for staffing qualifications and compensation, as appropriate, where staff encompasses leaders, educators, mentors/coaches, and specialists. In addition, centers would have to agree to accept children of specified ages, up to capacity, without discrimination with regard to income, special needs (except those requiring specialized programs), race/ethnicity, or religious background.

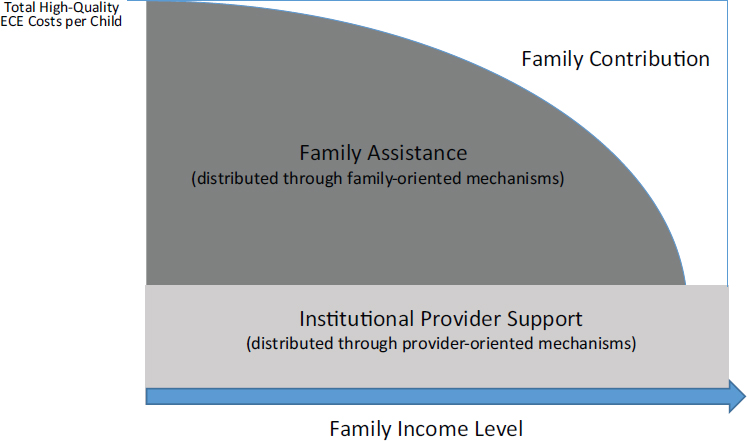

Family assistance, including ECE assistance programs and tax preferences, should ensure that families of all income groups can access high-quality early care and education. The levels of assistance and family payment amounts in ECE programs that charge a fee would be determined on a progressive scale, with the share of household income used for affordable payments increasing as income rises. This progressive scale would reverse the current pattern, in which lower-income families not eligible for no-fee ECE options pay a larger share of household income than do higher-income families. Figure 7-4 illustrates such a financing structure, showing how the total cost of a high-quality ECE system would be covered using institutional support, family assistance, and if applicable, family contributions.

Combining institutional support and family assistance has the potential to reduce economic segregation. Programs currently receiving institutional support but serving only low-income children could also serve children from other socioeconomic backgrounds, using family assistance to ensure that the costs of high-quality early care and education are met. Of course, geographic and socioeconomic segregation in housing may impede providers’ ability to attract socioeconomically diverse families.

NOTES: The total cost of providing high-quality early care and education per child is fixed, regardless of financing mechanism or revenue stream. Family-oriented mechanisms include tax preferences and ECE assistance programs; provider-oriented mechanisms include grants, contracts, or direct operating funds. At the lowest level of family income, no family contribution (from household income) is needed. The family contribution increases steadily as family income rises until the “top-out” income is reached, above which the family contribution covers all of the per-child cost not covered by institutional provider support. If a program chose to offer services on a no-fee basis, the family contribution would be zero and family assistance would cover that portion of costs.

A major challenge to implementing such a harmonized system of support is balancing federal standards with reasonable state flexibility. Currently, for the CCDF portion of family assistance, states are granted the flexibility to determine a family’s eligibility for assistance. As described in Chapter 3, this discretion has resulted in great variation among the states, with 17 states setting eligibility standards so that families with an income above 150 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) do not qualify for assistance, even though a family generally needs an income equal to at least 200 percent of the FPL to meet housing, food, childcare, transportation, health care, and other needs (Schulman and Blank, 2016).7

___________________

7 Families with incomes just above 100 percent of the FPL ($20,160 a year for a family of three in 2016) could qualify for ECE assistance in all states in 2016. However, families with incomes above 150 percent of the FPL ($30,240 a year for a family of three in 2016) did not qualify for assistance in 17 states, and families with incomes above 200 percent of the FPL ($40,320 a year for a family of three in 2016) did not qualify for assistance in 39 states (Schulman and Blank, 2016, p. 6).

Because the large majority of tax preferences that assist families come from the federal tax code, elimination of state flexibility regarding eligibility for ECE assistance programs is required to avoid gaps that arise for many middle-income families. These families are currently unable to access funding from ECE assistance programs because they exceed the income eligibility threshold set by their state, yet they do not benefit from federal and state tax preferences because their incomes are not high enough to incur a tax liability. Harmonizing the eligibility standards for ECE assistance programs and implementing tax preferences that are equitably progressive across income groups would increase ECE access for children from low-income families and eliminate the middle-income gap, provided that the states and the federal government adequately fund their ECE assistance programs so that all eligible families are served. States could choose to assist middle-income families through either tax preferences or through ECE assistance programs.

Although harmonizing provider-oriented and family-oriented mechanisms has the potential to allow providers to invest in raising staff salaries and supports, recruiting qualified personnel, and expanding or improving facilities, the current ECE financing structure lacks the stability and ensured funding that would allow providers to invest in these quality improvements. Other public programs have addressed these problems through advanced, multiyear funding. For example, federal elementary-secondary education grants are advance-funded. That is, federal contributions to elementary-secondary operating funds are appropriated annually, but on an advanced basis, with each year’s appropriation supporting expenditures in the following year. With the following year’s funding known and ensured, states and districts can initiate staffing and curriculum development activities in advance of the year in which they are needed. A similar approach for early care and education would provide similar value for ECE providers, families, and the ECE workforce.

Multiyear funding will also be critical during the transition period, and funds could be appropriated and allocated on a multiyear basis according to each phase of transition. For example, the committee’s illustrative cost estimate provides for transition to a high-quality ECE system over four phases (see Chapter 6). Under such conditions, funds could be appropriated and allocated for each of the four phases, enabling providers to recoup the cost of investments necessary to meet or exceed high quality-standards and investments in quality assurance to measure progress toward quality and make adjustments to the system as needed.

State-Level Coordination

Recommendation 3: In states that have demonstrated a readiness to implement a financing structure that advances principles for a high-quality ECE system and includes adequate funding, state governments or other state-level entities should act as coordinators for the various federal and state financing mechanisms that support early care and education, with the exception of federal and state tax preferences that flow directly to families.

The current structure of multiple ECE financing mechanisms places a heavy burden on providers, who must manage the various sources of funds. This complex structure also contributes to the fragmentation of the ECE landscape. To maintain multiple revenue streams and financing mechanisms supporting early care and education, while also eliminating this administrative burden placed on providers, state governments should act as coordinators of most of the revenue streams and financing mechanisms supporting early care and education. Allowing states to coordinate multiple revenue streams and financing mechanisms should only occur after a state has demonstrated a readiness to implement a financing structure that advances the principles for high-quality early care and education, including adequate and integrated funding for service delivery with appropriate qualifications and compensation for the workforce, workforce supports, and systems supports such as mechanisms for accountability and improvement and the adoption of consistent high quality-standards. The exceptions to this coordinator role for states are the federal and state tax preferences that flow directly to families.8

To foster efficiency and reduce administrative redundancy, states, as coordinators, should distribute federal and state funds to providers and families and have ample flexibility to create an administrative structure to fit their needs. States may choose to manage the process themselves or create a quasi-governmental entity or public/private intermediary organization at the state level to act as the coordinator. For example, in its implementation of its EarlyLearn initiative, New York City illustrates how such a “state-level coordinator” could act, as explained in Box 7-2. If state-level coordination is adopted, then additional legislative authorization may be required.

The committee emphasizes that coordination should not come at the expense of high-quality services, and high quality-standards should not be subjugated to administrative flexibility. Coordination of revenue streams and financing mechanisms should only occur after the federal government

___________________

8 As noted above, tax preferences would be harmonized with other family-oriented mechanisms to increase access for children from low-income families and eliminate the middle-income gap.

and the states have established and implemented consistent, high quality-standards and cost-based payments in accordance with Recommendation 1. As the committee recognizes, achieving a high-quality system will not occur overnight, and the committee’s proposal for phased-in implementation recognizes that there will need to be a transition period. Recommendation 3 will necessarily occur after such a transition period and only once a state has demonstrated a readiness to act as a coordinator. One way, for example, a state may demonstrate a readiness to implement Recommendation 3 is by showing that it is meeting or exceeding Head Start standards in its prekindergarten programs and investing adequate funds to meet the cost of delivering high-quality early care and education to infants and toddlers. Another way in which states may demonstrate readiness would be by serving as a successful Early Head Start (EHS) grantee (which they are currently permitted to do), meaning the state, as the lead, shows a willingness to adhere to and implement EHS standards and its comprehensive program approach. In addition, that state’s incorporation of the EHS standards and approaches into other state-based programs beyond EHS could be considered.

Such a coordinated financing structure would retain multiple financing mechanisms, such as provider-oriented financing for Head Start programs and family-oriented financing for subsidies for ECE services through the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF). Retaining multiple revenue streams and financing mechanisms allows flexibility to address the differing needs of providers and the needs of families of different socioeconomic means. In an analysis of federal ECE financing, the Government Accountability Office suggested that there were positives to retention of multiple financing mechanisms (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2017). For example, some families may receive Head Start services but also may need ECE services during nonstandard work hours. Conversely, if the family received only a subsidy for ECE services through CCDF, the child would not receive the comprehensive services provided by Head Start that are needed for healthy development and learning.

The committee stresses that we are not recommending that federal revenue streams be consolidated and distributed to states in the form of block grants. While proponents of block grants argue that they increase government efficiency and program effectiveness, critics of block grants argue that they are used to reduce government spending and that they decrease accountability (Dilger and Boyd, 2014). Though declines in funding are not intrinsic in the structure of block grants, the recent history has been that the creation of federal block grant programs to replace funding streams through federal programs has led to decreased federal funding. Several analyses of federal block grant programs have demonstrated that “even if a new block grant’s funding in its initial year is similar to the existing

funding for the programs merged into that block grant, the initial level likely won’t be sustained” (Reich et al., 2017, p. 1). Conversely, funding for CCDF has actually grown since its inception in 1997—although funding has declined from its peak in 2000, down by 3 percent, adjusted for inflation and population growth (Reich et al., 2017, p. 4; see also Dilger and Boyd, 2014; Finegold, Wherry, and Schardin, 2004). As discussed later in Recommendation 4, the committee strongly supports a significant ongoing federal role with corresponding investment of funds to build a system of high-quality early care and education that includes an infrastructure for support and accountability. Therefore, Recommendation 3 should be read in light of the other recommendations in this chapter, particularly Recommendations 1 and 4.

SHARING THE COST FOR HIGH-QUALITY EARLY CARE AND EDUCATION

The cost of providing high-quality early care and education far exceeds the amount of funding currently in the system. The committee has no magic revenue source to propose. The reality is that substantial increases in funding are needed to realize the envisioned transformation of the ECE system. To build adequate, equitable, and sustainable financing with effective incentives for quality, additional resources will need to come from a combination of public and private resources, with the largest portion of the necessary increase coming from public investments. These multiple sources of revenue may come from families, employers and the private sector, the public sector, or various combinations of these sources, but revenue should be raised in ways that ensure that the burden of neither family payments nor tax revenue collection falls disproportionately on those families with the fewest resources.

Public Share of Costs

Recommendation 4: To provide adequate, equitable, and sustainable funding for a unified, high-quality system of early care and education for all children from birth to kindergarten entry, federal and state governments should increase funding levels and revise tax preferences to ensure adequate funding.

Existing financing mechanisms fail to serve many low-income families eligible for assistance and families ineligible for assistance but priced-out of accessing high-quality ECE services, indicating a need for greater public investments to ensure that all eligible children can participate in early care and education. Moreover, as ECE costs increase over the phased transition

period, the public’s share of cost will necessarily increase because higher quality-standards and costs will make ECE services less affordable for additional families unless they receive public or private assistance.

The committee is cognizant that consideration must be given to the total amount of funding required. The committee’s illustrative estimate is that by the final phase of implementation, our recommendations would require at least $140 billion of annual funding, equivalent to about three-quarters of 1 percent (0.75%) of U.S. gross domestic product (GDP), or slightly less than the current average of 0.8 percent of GDP allocated to early care and education for the nations in the OECD.9 The committee’s illustrative estimate of an affordable family contribution would yield about a $58 billion share of this total ECE system cost, leaving a requirement of at least $82 billion in public funding, which is an increase of about $53 billion over the current level. If a structure with no family contributions were enacted, it would require an annual increase of at least $111 billion to reach the total cost of at least $140 billion. If the costs of the recommended financing structure exceed that which policy makers are willing to allocate, then the potential results are either a failure to act or an allocation of funding inadequate, according to our analysis and assumptions, to achieve the committee’s primary objectives of high-quality ECE services with a well-compensated workforce that are affordable for all families.

How the burden can best be distributed among levels of government and among revenue sources must be determined through political processes in which decision makers weigh different options for transitioning to and implementing a high-quality ECE system and weigh the benefits of such a system against the potential political and economic costs of reducing other public expenditures or raising taxes. But the dual function of the nation’s ECE structure as providing early care and education for a critical period in child development and as economic security for families with parents in the workforce argues for continued public responsibility for ensuring ECE access for all children. The committee supports an ongoing significant federal role but also supports important roles for state and local governments.10

___________________

9 The current OECD average spending on early care and education is 0.8 percent of GDP (Penn, 2017). The 2016 U.S. GDP was $18.6 trillion (World Bank, 2017).

10 Although the federal government does not have an explicit constitutional role in education, a number of judicial decisions have shaped the development of a federal role, including jurisprudence surrounding the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause. According to Harris and colleagues (2016, p. 9), “The quantity and quality of education children receive are significant determinants of life outcomes. Therefore, the protection of civil rights within this context, as well as support for education among the disadvantaged, is crucial to ensuring equal opportunity in society.” This reasoning underpins the requirement for federal investment in education.

Regardless of the division of ECE funding responsibilities between the federal and subnational governments, additional funds will need to come from natural economic growth in existing revenue sources, from redirecting current expenditures, from entirely new revenue sources, or a combination of these options. If new revenue sources are sought, policy makers will have to consider tradeoffs among revenue sources based not only on current tax structures but also on issues that entail value choices. Among the issues to consider is whether to rely on a dedicated revenue source or on general tax revenue. An advantage of a dedicated revenue source such as, for example, a gas tax to finance highway maintenance, is that once enacted it is not subject to the vagaries of annual appropriations. The downside in this context, though not inherent in the mechanism itself, is the possibility that revenue from the dedicated tax may not be sufficient to cover the full costs of a high-quality ECE system and is unlikely to be responsive to changes in the costs of providing high-quality early care and education.

In the following discussion, the committee presents some of the principles—including fairness, stability of the tax base over the economic cycle, revenue-raising potential, and minimizing tax-induced distortions—that should guide decision makers in their quest to identify the necessary revenues. In addition, the committee stresses that increased ECE costs should not be covered by reducing other essential services to children and families, as child and family well-being is multidimensional and requires a wide range of supports. Furthermore, any offsetting cost reductions should be achieved by actual efficiency gains, not by simply shifting the costs from the public to families or from one level of government to another.

One of the main criteria for a good revenue source is fairness. The committee accepts the view of many tax experts that a fair tax—especially for a service such as early care and education—is one in which the tax burden is distributed in line with a taxpayer’s ability to pay and, further, that the taxpaying unit’s income serves as a reasonable measure of its ability to pay. A tax would be deemed to be fair, for example, if it imposes the same burden on taxpayers with similar abilities to pay (often referred to as horizontal equity) and if it imposes higher taxes on those with more ability to pay than on those with less ability to pay (often referred to as vertical equity). With respect to vertical equity, reasonable people may disagree about the relative fairness of a progressive versus a proportional tax. Under a progressive tax, high-income taxpayers pay a higher percentage of their income for that tax than those with lower income. Under a proportional tax, all taxpayers pay the same percentage of income for that tax. In any case, the committee believes that most people would accept the view that regressive taxes—those that take a higher share of income from lower-income taxpayers than the share they take from higher-income taxpayers—would be unfair. For ECE financing, this fairness criterion would argue against financing based on,

for example, lottery revenues (defined as net revenue to the government after administrative expenses and payouts to the winners) both because the burden differs across families with similar income depending on how much they play the lottery and because the burden across all families would be regressive.

If policy makers are seeking revenue sources that distribute the burden progressively across taxpayers, income taxes are a viable option because income taxes at the federal level are specifically designed to be progressive. Although most states also use income taxes, those taxes are more likely to be proportional because states have incentives to avoid highly progressive taxes that may have adverse effects on their local economies. Nonetheless, even proportional state income taxes are likely to be fairer than state sales taxes, which are likely to be regressive.

Payroll taxes are generally deemed to be regressive both because there is a cap on the level of earnings that is subject to the tax and because such taxes, even the portions that are nominally levied on the employer, are ultimately borne by employees in the form of lower wages. Raising the cap would make the tax more proportional with respect to wage income, but it still would not make it proportional with respect to total income because wage income accounts for a declining share of total household income, which includes both wages and unearned income (such as interest and rents), as household income rises.

A good tax source for funding a transformed ECE financing structure would also generate substantial revenue that is relatively stable over economic cycles, is sustainable, and increases with the growth of population and average wages. Stability of the tax base over the economic cycle is a desirable characteristic for a revenue source used to finance a service, such as early care and education, that must be delivered consistently over time. A tax at a specified rate on luxury items, for example, would fail the stability criterion because consumers are likely to spend more on such items when the economy is growing and to cut back when the economy is declining, thereby generating an uneven revenue flow. Further, the revenue source should be sustainable over time given the need for ongoing public revenue for ECE services. Based on this consideration (along with the fairness criterion), taxes on items such as tobacco or soft drinks are problematic for financing early care and education since, if the taxes have the intended effects, spending on such items will decline over time. In addition, the committee concludes that it would be desirable, to the extent possible, to rely on tax bases that grow along with population and general wages. Population growth is likely to increase the demand for quality ECE services, and overall wage growth is likely to increase the personnel costs of providing high-quality early care and education. By minimizing the need for frequent politically contentious debates about the level of the tax rate, reliance on

tax bases that grow with increases in these ECE cost drivers will help ensure that revenue will be available to cover the rising costs of high-quality early care and education.11

Finally, any tax raises legitimate concerns that it may distort people’s behavior in undesirable ways, distortions that economists refer to as inefficiencies. A high marginal tax rate on earned income, for example, may induce some people to work fewer hours; a high sales tax on consumer goods may induce consumers to shift their consumption away from taxed goods in favor of untaxed goods. Such distortions are largest and most problematic when tax rates are high. One way to lessen such distortions is to rely on broad-based taxes that can generate substantial revenue with relatively low tax rates.12 This line of reasoning would render broad-based taxes such as those on income or sales superior to taxes on narrower bases such as corporate profits or selected consumption goods. Moreover, such considerations would argue for relying on several revenue sources, each taxed at relatively lower rates, rather than a single revenue source taxed at a relatively high rate.

Although it might be tempting to view public sector borrowing as an additional revenue source, that approach is problematic. As discussed in Chapter 3, paying for ECE facilities by issuing bonds is a sensible financing strategy for high upfront costs, given the lumpiness of expenditures on facilities. Ultimately, however, that strategy does not obviate the need to increase taxes to pay the debt service (which includes both interest and principal payments) on the bond. Bond financing simply changes the timing of the tax increase by spreading the burden out over time.

Families’ Share of Costs

Recommendation 5: Family payments for families at the lowest income level should be reduced to zero, and if a family contribution is required by a program, that contribution, as a share of family income, should progressively increase as income rises.

___________________

11 The committee acknowledges, however, that some observers may object to relying on revenue sources that grow with population and wages on the ground that the automatic revenue growth generated by such sources may keep policy makers from fulfilling their responsibility to closely monitor and evaluate funding levels.

12 There is no controversy in the economics literature about the observation that distortions rise more than proportionately with the tax rate. More controversial is how this observation is best used by policy makers. On one side are economists such as Richard Musgrave who believe in the positive role of government and would support broad-based taxes, given the desirability of raising revenue in ways that minimize distortions, other considerations held constant. That is the perspective taken by this committee. On the other side are economists such as James Buchanan who believe that tax policies should be designed specifically to keep government from expanding (Buchanan and Musgrave, 1999; see also Brennan and Buchanan, 1977).

In the United States, families pay the majority of ECE expenditures for children under age 5 years. By comparison, public K–12 education is delivered with no fees charged to families.13 The financial burden on non-affluent parents affects their decisions about using ECE services, including the amount, type, and quality of service they use. In the current system, some families are priced out of participating in paid ECE services due to unaffordable fees. Moreover, the fees paid by low- and middle-income families in the current system account for a much greater share of household income than the fees paid by more affluent families, resulting in a regressive financing structure that does not allocate limited funds to those most in need. While parents may contribute some portion to the costs of an improved ECE system, relying solely on parents to shoulder the burden for increased costs of higher-quality early care and education would likely lead to reductions in the use of high-quality ECE options and increased economic insecurity, resulting in less support for children’s early learning, development, and well-being.

While current levels of family payments clearly make early care and education unaffordable for many low- and middle-income families, determining what share of total ECE system costs families should pay is challenging, and the evolving policy and practice landscape in early care and education does not provide an unequivocal path forward. There are several approaches to determining a reasonable share for families to pay, where “reasonable share” means finding a balance between ensuring that significant economic barriers do not prevent families from using high-quality ECE services; increasing progressivity through family payments, tax revenue collection, or some combination of both; and ensuring that public revenues are expended reasonably (see discussion in Appendix C). A number of states and localities have implemented universal ECE programs, specifically prekindergarten programs, on a free, no-fee basis to all children, similar to public provision of kindergarten and elementary and secondary education. For example, Oklahoma and Georgia have established universal prekindergarten programs, some of which are offered with no out-of-pocket costs to parents. Other localities, such as Washington, D.C., and New York City, have also implemented universal prekindergarten programs that do not require parental payments. In other states, courts have included early education, for children of certain ages, as part of the right to education protected by state constitutions, while in some countries, for instance Germany and Nordic countries, access to ECE services is defined as a legal right, where demand must be met and relevant resources provided (Penn,

___________________

13 Some kindergarten programs are provided on a no-fee basis, but some states allow school districts to charge a fee for full-day kindergarten programs (Parker, Diffey, and Atchison, 2016).

2017). However, the average ECE fees paid by families in the OECD member countries, for the programs to which they apply, represent 15 percent of household income, so the poorest and largest families pay less (Penn, 2017).14,15 The committee discusses below the advantages and disadvantages of both no-fee approaches and approaches that require families to contribute an affordable share of costs.

As noted above, in K–12 public education fees are not charged to families; instead, the costs of delivering K–12 education are shared across the citizenry, and no family pays to ensure a place for its children.16 This practice is part of the longstanding tradition in the United States that education is a public good, but this tradition has applied only to older children, namely those in grade 1 and older. Systemwide no-fee approaches for early care and education can help to reduce economic insecurity and boost the disposable income of families with young children, particularly where poverty is highly concentrated but also for many low- and middle-income families that may not be in poverty but may be economically insecure. A systemwide no-fee approach may also promote integration in ECE settings of children from across socioeconomic classes, if programs are designed and located to serve diverse groups of children without regard to family income. Such integration has been shown to benefit all children. A no-fee approach reduces or eliminates the financial barriers to ECE participation. However, not charging fees to any family transfers resources from the public to the affluent, in effect subsidizing high-income families, as is true in K–12 education but not true in other publicly supported goods such as housing and health care (see, e.g., Cascio, 2015). Such a financing structure lacks target efficiency for resources, but target efficiency could be improved if the tax revenues for the public share of ECE costs are generated progressively.

Asking families to contribute some of the cost of early care and education mirrors the financing structure of the higher education, housing, and health-care systems, in which families are expected to contribute to the cost of services used. An affordable family contribution can result in a progressive financing structure that targets resources to those most in need, reduces public costs, and retains an additional revenue stream. Requiring an

___________________

14 See the OECD database at https://www.oecd.org/els/family/database.htm [December 2017].

15 Expenditure profiles on early care and education in OECD and EU countries differ a great deal and vary according to the availability of wider social benefits such as maternal and parental leave, income support, and health coverage (Penn, 2017).

16 Some kindergarten programs are provided on a no-fee basis, but some states allow school districts to charge a fee for full-day kindergarten programs (Parker, Diffey, and Atchison, 2016). Kindergarten was incorporated into most public school systems in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s, lowering the age of formal, public education to 5 years of age (see Chapter 2).

affordable family contribution, according to some economic literature, may also encourage parents to be more-informed consumers and may encourage ECE providers to be “cost-conscious” (see, e.g., Johnstone, 2003).

On a programmatic level, U.S. experiences in Head Start/Early Head Start and some state and local universal prekindergarten programs, as well as kindergarten programs, demonstrate that no-fee approaches for certain programs eliminate financial barriers to utilization and could ensure that participation in early care and education does not depend on family circumstances, greatly improving access. Like systemwide no-fee approaches, requiring no family contributions for these programs helps to promote equity, reduce poverty, and limit the administrative burden on providers. However, if the higher public cost of no-fee programs causes policy makers to limit eligibility to only low-income children, one consequence may be the promotion of harmful economic segregation.

Decision makers at the state and local level will need to balance the advantages and disadvantages of offering systemwide no-fee approaches, no-fee approaches for some programs, or requiring families to make an affordable contribution. If programs require a family contribution, a restructured family payment schedule that requires less from low- and middle-income families and progressively more from higher-income families will be needed to eliminate barriers to utilization and achieve an equitable distribution of family contributions.17

Other Private Sector Stakeholders

The nonparental private sector (including businesses/employers, corporate foundations, and philanthropic organizations) currently plays an important role in championing early care and education. While employers’ and philanthropies’ financial contributions to early care and education are small relative to the scale of the contributions of parents and the public sector, this sector’s leadership and active participation in asserting the importance of and setting the vision for systemic transformation are essential. The private sector has the potential to play a critical role advocating for policies and leveraging available dollars to support high-quality ECE services and systems, particularly during the transition phases for moving from the current fragmented and failing system to an effective, high-quality ECE system (see discussion of the nonparental private sector’s role in facilitating the transition to high-quality early care and education in the next section).

___________________

17Chapter 6 provides an illustration of one possible way to structure progressive family contributions.

PLANNING FOR THE TRANSITION TO HIGH QUALITY

Recommendation 6: A coalition of public and private funders, in coordination with other key stakeholders, should support the development and implementation of a first round of local-, state-, and national-level strategic business plans to guide transitions toward a reformed financing structure for high-quality early care and education.

The committee’s vision outlines a child-centered financing strategy whereby access does not depend on families’ circumstances, financing is conditional on ECE programs and services meeting high quality-standards, and funding is set to levels to meet the total cost of high-quality early care and education. However, because early care and education is currently fragmented, implementation of the committee’s vision will require a transition period for incrementally building toward integration of currently distinct parts of the ECE landscape (service delivery, system-level workforce supports, and quality assurance and improvement systems). The process of transitioning from the current structure to the committee’s vision of an integrated system will take time, resources, and intentional coordination and planning.

While the committee is unaware of a systematic review of the impact of the nonparental private sector in transforming systems, as noted above, key entities in the nonparental private sector have played an essential role in supporting transformation in the ECE field. Currently, they support high-quality early care and education in a number of ways, including offering family-friendly policies to their employees; providing benefits or incentives for employees, including onsite or discounted child care (though most employer benefits are nonfinancial); championing change in their communities as public policy and budgeting advocates and intermediaries; and directly supporting quality ECE services through direct corporate contribution, pay-for-success strategies, shared services alliances (SSAs), business technical assistance centers, and experimental model programs.

During the transition period, the nonparental private sector will continue to be an important stakeholder and may build coalitions to support initiatives to bring about systematic change, leverage investments to drive implementation of a new financing structure, and hold the public sector accountable for improving quality in early care and education for children and for the ECE workforce. Engaging and developing public and private partnerships will also be important in planning for the transition to high quality, in order to leverage resources and build constituencies and commitment to moving toward high quality. For example, the Virginia Early Childhood Foundation is a public-private partnership that, in its work to support the development of a well-qualified ECE workforce in Virginia, has shown how the nonparental private sector can be a crucial partner during the transition period, as explained in Box-7-3.

In summary, the nonparental private sector, specifically private funders engaged in supporting high-quality early care and education, should work with public funders and other key stakeholders, including State Advisory Councils on Early Childhood Education and Care18 and similar statewide and national coordinating bodies, as well as interested parent, provider (center-based and home-based), and ECE workforce representatives, to develop and implement local-, state-, and national-level strategic business plans to guide transitions toward a reformed financing structure for high-quality early care and education, with a specific emphasis on business, financial, and systems strategies.

At the national level, a strategic business plan would outline national goals and inform and coordinate state plans. This planning would include identifying strategies for increasing resources, assessing and monitoring progress against these goals, ensuring accountability throughout the financing system, and articulating and developing a coordinated research agenda. Such a planning process would facilitate coordination at the federal level among federal agencies and other national stakeholders to streamline the financing for monitoring and technical assistance structures, coordinate federal supports for the professional development of the ECE workforce—including supports to ensure diversity across professional roles—and harmonize federal data collection and research efforts, among others.

State-level and community-level plans could outline specific strategies for addressing quality components in their specific contexts, including

___________________

18 Funded through the Administration for Children and Families and state resources, State Advisory Councils on Early Childhood Education and Care are “charged with developing a high-quality, comprehensive system of early childhood development and care” and “ensure statewide coordination and collaboration among the wide range of early childhood programs and services in the state, including childcare, Head Start, IDEA preschool [prekindergarten] and infants and families programs, and prekindergarten programs and services” (available: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ecd/early-learning/state-advisory-councils [December 2017]). These state councils are required to undertake the following activities: “conducting periodic statewide needs assessments on the quality and availability of early childhood education and development programs and services from birth to school entry; identifying opportunities for, and barriers to, collaboration and coordination; developing recommendations on increasing participation in child care and early education programs, including outreach to underrepresented and special populations; developing recommendations on the development of a unified data collection system for public early childhood and development programs and services; developing recommendations on statewide professional development and career advancement plans for early childhood educators; assessing the capacity and effectiveness of institutes of higher education supporting the development of early childhood educators; making recommendations for improvements in state early learning standards and undertake [sic] efforts to develop high-quality comprehensive early learning standards, as appropriated; and facilitating the development or enhancement of high-quality systems for early childhood education and care designed to improve school readiness” (available: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ecd/early-learning/state-advisory-councils [December 2017]).

strategies for increasing staff compensation and setting workplace standards, building the supply of high-quality ECE providers, and engaging public and private partners in support of additional resources. In addition, the planning process undertaken by states and communities may bring together stakeholders to identify resources for support of initiatives for improving the career and education pathways available to the ECE workforce, to sequence transition efforts to improve access to high-quality ECE for children across age groups, or to identify resources for facilities improvements in their communities.

Local-, state-, and national-level planning efforts, taken together, are critical to facilitating the implementation of an integrated financing system as envisioned in this report by identifying key stakeholders charged with moving the plans forward, building constituencies to support systemic transformation, and leveraging resources to bring about high-quality early care and education that is affordable and accessible for all children.

FINANCING WORKFORCE TRANSFORMATION

The transitional period necessary to build a more coherently financed ECE system with a highly qualified workforce will likely require specific types of supports and significant funding in the short term to ensure that each quality component is adequately addressed. This section discusses special considerations, related to improved staff compensation, higher education, and professional development, that will be required during the transition to high-quality early care and education with a highly qualified workforce.

Staff Compensation

As described in the Transforming report, linking qualifications to compensation is an essential element of quality and higher compensation levels foster the recruitment and retention of a highly qualified workforce (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2015, pp. 461–478). However, in the currently underfunded system, qualification requirements have not driven compensation to adequate levels, suggesting a need for intervention in the market, at least during the transition period (see Chapter 3). That is, increased funding to the system and programs is a necessary but not sufficient condition for better pay.

Ensuring that increased per-child funding translates into better compensation for the ECE workforce is complex. While various workforce-oriented financing mechanisms have been used to supplement ECE professionals’ compensation, these mechanisms in the current system have been insufficient to raise compensation to an adequate level at scale. The temporary

nature of the supplements also does not create the predictable and steady salaries necessary for recruiting and retaining a highly qualified workforce. Increasing income to the program is also not guaranteed to lead to higher salaries for ECE educators employed in centers, homes, or schools.19 For example, historically in voucher programs, because income to the provider fluctuates when a child’s participation in that ECE setting changes, administrators tend to be wary of increasing salaries, given that the ongoing resources are not reasonably reliable. Further, if only some children are subsidized, increased resources from these subsidies may not be sufficient to bolster salaries for all educator staff.20 On the other hand, some state prekindergarten programs have recently made strides on increasing base pay for ECE educators through contracts between funders and providers that set requirements on compensation levels that directly guarantee adequate compensation for ECE professionals (see Chapter 3).

While the transition to a highly qualified and adequately compensated workforce is taking place, ensuring that the workforce is receiving improved compensation will require testing the market’s response and accountability with some experimentation around sufficiently robust and dependable mechanisms. Because QRISs communicate important messages about what areas are deemed most important for focusing resources and attention, engaging the state’s QRIS in wage guidelines might be important. However, it is unclear what role QRISs could play in setting wage guidelines. To date, only some QRISs identify whether a program has a salary schedule, but even these systems do not provide direction as to the schedule’s parameters.

Onsite Professional Development

As discussed in the Transforming report, educational qualifications and compensation are instrumental to high-quality early care and education but cannot in themselves guarantee high quality. It is essential that educators and leaders engage in consistent professional learning and professional development experiences during ongoing practice. Such experiences include pedagogical leadership training, coaching and mentoring, business

___________________

19 For home-based providers that operate as small businesses with one owner/educator, institutional support and per-child reimbursements apply more directly to educator earnings. Additional mechanisms to link per-child funding to compensation will likely not be necessary, though stipends and tax credits could benefit home-based providers directly, as well as other providers. As with center employees, some wage guidance for additional individuals employed in home-based settings will likely be required to ensure that increased rates to home-based providers support improved wages for their non-owner employees.

20 This may also occur if higher reimbursements are targeted only to certain children, as in the case of prekindergarten classrooms in community-based programs, where educators in one room may earn less than their equivalently qualified colleague in the next classroom.

training and technical assistance, paid time for attending onsite professional development activities, paid time for planning and assessment and for professional sharing and reflection, and training to support the needs of children with disabilities and other special needs. These support components would add to onsite costs because they require additional staffing: hiring of coaches and mentors, substitutes to allow for release time to attend offsite courses and training, and staff support to give educators non-child-contact time for planning and assessment. Other supports will need to be financed at the system level (see discussion below).

System-level Workforce Development

Recommendation 7: Because compensation for the ECE workforce is not currently commensurate with desired qualifications, the ECE workforce should be provided with financial assistance to increase practitioners’ knowledge and competencies and to achieve required qualifications through higher-education programs, credentialing programs, and other forms of professional learning. The incumbent ECE workforce should bear no cost for increasing practitioners’ knowledge base, competencies, and qualifications, and the entering workforce should be assisted to limit costs to a reasonable proportion of postgraduate earnings, with a goal of maintaining and further promoting diversity in the pipeline of ECE professionals.

The committee views the following points to be essential aspects of fulfilling this general recommendation:

7a. Existing grant-based resources should be leveraged, and states and localities, along with colleges and universities, should work together to provide additional resources and supports to the incumbent workforce, as practitioners further their qualifications as professionals in the ECE field.

7b. States and the federal government should provide financial and other appropriate supports to limit to a reasonable proportion of expected postgraduate earnings any tuition and fee expenses that are incurred by prospective ECE professionals and are not covered by existing financial aid programs.

Recommendation 8: States and the federal government should provide grants to institutions and systems of postsecondary education to develop faculty and ECE programs and to align ECE curricula with the science of child development and early learning and with principles of high-quality professional practice. Federal funding should be leveraged through grants

that provide incentives to states, colleges, and universities to ensure higher-education programs are of high quality and aligned with workforce needs, including evaluating and monitoring student outcomes, curricula, and processes.

Resources for system-level workforce development, including higher education and professional development, will be needed to transition the current workforce to the highly qualified workforce envisioned in the Transforming report.

Currently in early care and education, and generally in other sectors, the cost for professional training is either borne directly by prospective employees or shared between the employee and the employer. However, because compensation for the ECE workforce is not currently commensurate with desired qualifications, the ECE workforce should be provided with financial assistance to increase practitioners’ knowledge and competencies and to achieve required qualifications through higher education programs, credentialing programs, and other forms of professional learning. The incumbent ECE workforce should bear no cost for increasing practitioners’ knowledge base, competencies, and qualifications, and those entering the ECE workforce should have financial assistance to limit their education costs to a reasonable proportion of postgraduate earnings, with a goal of maintaining and further promoting diversity in the pipeline of ECE professionals.

Due to the ECE workforce’s low levels of compensation, asking individuals to contribute out of pocket to their educational expenses or to cover them using loans that must be repaid with future wages is not feasible. Similarly, asking center- or home-based providers to cover educational costs in the current system could pose significant difficulties for many employers, especially for small-business ECE providers that operate with relatively limited budgetary discretion. For these reasons, additional federal and state funding will be necessary to avoid disrupting service provision.

A number of grant-based resources for higher education are currently available from the federal government, states, private entities, and individual colleges and universities (see Chapter 3). These resources should be leveraged to offset the costs of tuition and fees for ECE professionals pursuing higher education. Additional funding may also be necessary to ensure that ECE professionals are able to pursue higher education and other forms of credentialing at an affordable rate. States and localities, along with colleges and universities, should work together to provide these additional resources to the incumbent workforce as practitioners further their qualifications as professionals in the ECE field. They should have the flexibility to determine certain requirements for supports, such as number of years in service required to qualify for assistance and length of commitment required after completing training.

These recommendations assume improved compensation for the ECE workforce at the conclusion of the phased transition period because adequate compensation will be necessary to retain these highly qualified professionals in ECE positions (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2015, pp. 461–478). Once compensation reaches adequate levels, it may be appropriate to ask ECE professionals to contribute to their costs of attaining additional qualifications as ECE professionals, either through their own savings or through the use of student loans. However, the amount that these professionals should be expected to contribute should be a small percentage of their expected earnings upon completion of their degree.21 States should use their public colleges and universities to promote high-quality, affordable higher education and training for ECE professionals, and they should create options for private institutions within the state to develop high-quality, affordable opportunities. This needed support includes providing financial and other appropriate supports to prospective ECE professionals to limit any tuition and fee expenses not covered by existing financial aid programs to a reasonable proportion of postgraduate earnings. Targeted financing mechanisms to support professionals with culturally, linguistically, and professionally diverse backgrounds who are pursuing opportunities for higher education will also be needed, to reduce the racial and ethnic stratification present across job roles in the current ECE workforce.

States should also promote greater alignment of higher-education programs with the core competencies needed by ECE professionals, including pedagogical leadership, to ensure positive outcomes for children. Since state budgets often face many other pressures and funding for higher education has been declining in many states, federal funding may be necessary to further incentivize high-quality higher education by providing grants to state systems and to colleges and universities, to align curricula with the science of child development and early learning and with the principles of high-quality professional practice, to ensure affordability for the ECE workforce and to support faculty and program development.