3

Sexual Harassment in Academic Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine

While much of the research on sexual harassment has focused on workplaces outside academia, the research reviewed in this chapter suggests that academia should not be considered an exception and that it faces similar rates of sexual harassment.1 The goal of this chapter is to analyze the extent to which all three forms of sexual harassment2 occur in academia, specifically in the fields of science, engineering, and medicine; consider the overall culture and subcultures in which it takes place; and identify conditions that increase the probability that sexual harassment behaviors will occur. This analysis aims to shed light on the extent to which women experience sexual harassment in science, engineering, and medicine; compare experiences across different environments; and understand how the organizational makeup of these fields contributes to the risk for sexual harassment. This chapter reviews how academia and academic science, engineering, and medicine specifically are unique environments in terms of sexual harassment.

___________________

1 Wherever possible, the report cites the most recent scientific studies of a topic. That said, the empirical research into sexual harassment, using rigorous scientific methods, dates back to the 1980s. This report cites conclusions from the earlier work when those results reveal historical trends or patterns over time. It also cites results from earlier studies when there is no theoretical reason to expect findings to have changed with the passage time. For example, the inverse relationship between sexual harassment and job satisfaction is a robust one: the more an individual is harassed on the job, the less she or he likes that job. That basic finding has not changed over the course of 30 years, and there is no reason to expect that it will.

2 The three types of sexual harassment are gender harassment, unwanted sexual attention, and sexual coercion. See Chapter 2 for further descriptions.

THE ACADEMIC ENVIRONMENT IN SCIENCE, ENGINEERING, AND MEDICINE

The main conditions that increase the risk of sexual harassment being perpetrated against women—organizational tolerance for sexual harassment and male-dominated environments3—are ones that appear in academia generally, and specifically within the fields of science, engineering, and medicine.

Higher education environments are perceived as permissive environments in part because when targets report, they are either retaliated against4 or nothing happens to the perpetrator. In a recent paper, one respondent who reported her experience of psychological and physical harassment from her advisor described the response to her reporting the experience in this way:

So when I did talk to the faculty director or the chair of the department, I’d say that they gave us no choice but to leave the department. . . . After leaving the institution, the next year this advisor got three more students. There was no sort of repercussion. . . . I felt like I had this type of plague or something . . . it’s forcing the person who was victimized to keep confronting and keep pushing. (Nelson et al. 2017, 6)

Higher education is also replete with cases where offenders are an “open secret” but are not sanctioned (Cantalupo and Kidder 2017). Interviews, conducted by RTI International with female faculty in science, engineering, and medicine who experienced sexually harassing behavior, reveal some of the issues that explain this general climate of accepting sexual harassment (RTI 2018).5 The interview responses demonstrate that the behavior of male colleagues, whom higher-ranking faculty or administrators perceived as “superstars” in their particular substantive area, was often minimized or ignored. Even men who did not have the superstar label were often described as receiving preferential treatment and excused for gender-biased and sexually harassing behavior.

I think also sometimes people are blinded by good signs and shiny personalities. Because those things tend to go hand in hand. You don’t want to think that this person who’s doing incredible work in getting all of these grants, is also someone who has created a negative environment for others. I’ve seen this over and over again. (Nontenure-track faculty member in psychology)

A theme that emerged in the interview data was that respondents and other colleagues often clearly knew which individuals had a history of sexually harassing behavior. The warnings were provided by both male and female colleagues, and were often accompanied by advice that trying to take actions against these

___________________

3 See the discussion in Chapter 2 for more details on this research.

4 See the discussion in Chapter 4 about retaliation and the limits of the law to protect against it.

5 This research was commissioned by the committee, and the full report on this research is available in Appendix C.

perpetrators was fruitless and that the best options for dealing with the behavior were to avoid or ignore it. Many respondents described the dialogue among women faculty to warn about or disclose sexually harassing behaviors as an unfortunate shared bond that was far too often the norm.

Similarly, expectations around behavior were often noted as an “excuse” for older generations of faculty, primarily men, to perpetrate sexually harassing behavior. Many respondents noted that the “old guard,” in perpetrating this type of behavior, was doing what they have always done and was not likely to change, because of a general acceptance within academic settings.

This is kind of a new thing that—and the mindset is so ingrained, like the people that say these things, they don’t even realize that they are—so their intent is not to sexually harass people, but they do it automatically, and they don’t even think about it. (Professor in geosciences)

The normalization of sexual harassment and gender bias was also noted as fueling this behavior in new cohorts of sciences, engineering, and medicine faculty. Respondents discussed the disheartening experiences of colleagues who entered training settings with nonbiased views and respectful behavior, but who concluded those experiences endorsing or dismissing sexually harassing and gender-biased behavior among themselves and others.

I still don’t think that the prospect of being sexually assaulted was as bad as watching the next generation of sexual harassers being formed. I think that was the worst part for me. (Nontenure-track faculty member in medicine)

Sometimes it takes many reports across multiple institutions for a perpetrator’s actions to even be acknowledged (Cantalupo and Kidder 2017). This reality, as well as the perception widely held across higher education, means that few targets believe their complaints will be taken seriously.

Because many American colleges and universities were formed for the express purpose to educate men, higher education environments are also often historically male dominated, and science, engineering, and medicine in higher education are still numerically and culturally male dominated. While women have earned more than half of all science and engineering bachelor’s degrees since 2000 (NCSES 2004, 2017), academic science and engineering as a whole continues to be very male dominated due to the high concentration of women in only a handful of specific scientific fields. As the National Science Foundation’s 2016 Science and Engineering Indicators points out, men and women tend to fall into different fields of study, and these tendencies are consistent at all levels of higher education degree attainment. In 2013 alone, men earned 80.7 percent of bachelor’s degrees awarded in engineering, 82 percent in computer sciences, and 80.9 percent in physics. Women, on the other hand, earned half or more of the bachelor’s degrees in psychology, biological sciences, agricultural sciences,

and all the broad fields within social sciences except for economics (NSF 2016). Even in biology-related fields where women make up more than one-half of all doctorate recipients, they are vastly underrepresented at the faculty level. A study by Jason Sheltzer and Joan Smith (2014) published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that of 2,062 life sciences faculty members at top-ranked programs in the United States, only 21 percent of full professors and 29 percent of assistant professors were women.

In medicine, although women have been earning medical degrees in numbers at least equal to men for several decades, female medical school faculty neither advance as rapidly nor are compensated as well as their male colleagues (Ash et al. 2004; Cochran et al. 2013). A survey conducted by the Association of American Medical Colleges further reveal the disparities in career advancement between men and women: 1 in 6 department chairs or deans were women in 2013–2014, up from 1 in 10 in 2003–2004; 38 percent, only a little more than a third, of full-time academic medicine faculty are women; and only 21 percent of full professors are women, as are 34 percent of full-time associate professors (AAMC 2014).

The culture of higher education workplaces, where boundaries between work and personal life are blurred and one is always “working,” are particularly difficult on people with child care or elder care responsibilities, as well as for people who do not conform to gendered expectations for behavior or appearance (Caplan 1993). These people are most often women and sexual- and gender-minority people. Historically, the life of the mind was believed to be men’s work, and while our society may have more enlightened views today on the contributions of women to higher education generally and science specifically, the structure of the academic workplace is still one best suited to men who have a wife at home serving as domestic caretaker full time (Valian 1999; Xie and Shauman 1998; NAS 2007). That is, the “ideal worker norm” is pervasive in academia. As Leskinen and Cortina (2014, 110) explain in their work on a broader conceptualization of gender harassment (a type of sexual harassment):

The ‘‘ideal worker’’ is someone who works full time and consistently over his or her lifetime and who takes no leaves for pregnancy, child care, or other care-giving responsibilities [Williams, 2000]. Employers value and reward the ideal worker, despite the inherent stereotypical sex-based expectations (i.e., workplaces are structured around male bodies) that this ideal endorses [Williams, 2008]. Conversely, some employers punish personnel who fail to meet the ideal worker norm; this notion of ‘‘family responsibilities discrimination’’ is gaining attention among lawyers and social scientists as a significant barrier to women’s employment and advancement [see Williams, 2008; Williams and Bornstein, 2008].

Furthermore, academic science, engineering, and medicine are hierarchical. At the graduate level, students have to rely on principal investigators who control

funding, research direction, and recruitment decisions. In academic medicine, there are clear hierarchical roles and the training encourages a respect and trust of those at the top of the hierarchy: starting with attending physicians, followed by fellows, residents, and interns, and then medical students at the bottom. When hierarchy operates out of habit rather than as something that is constantly reflected on and justified due to experience or expertise, misuses of power can increase.

The nature of mentoring in science, engineering, and medicine creates unique risks for trainees. The mentor-mentee relationship can involve much time spent alone together, in the lab, in the field, or in the hospital, and sometimes in isolated environments. It also involves significant dependence on one mentor or a small committee because research projects, education and career mentoring, and funding are often all tied to the advisor and not in the control of the student.

In the medical field, training specifically takes place in hospital settings, over 24-hour “call” periods. Interns and residents (even the nomenclature attests to the trainees having a special relationship to the hospital training space) provide much of the patient care under the direction of faculty attending physicians who may or may not be physically present in the hospital for the educational benefits. Caring for sick patients, especially in the emergency room, the operating rooms, and the intensive care units is obviously very intense, tiring, and stressful, and because of the requirement for extended duty hours, call rooms with single or multiple beds are close by for when sleep is possible. The risk they pose for sexual harassment and sexual assault should be obvious (Komaromy et al. 1993). Additionally, research on the medical environment reveals that overall “mistreatment” is commonplace in all levels of the medical hierarchy, especially among medical school students, interns, and residents in all specialties. Combined, these environmental and mentoring factors mean that there are increased opportunities for sexual harassment perpetration, in environments with little structure or accountability for the faculty member, and a decreased ability for students to leave without professional repercussions (Sekreta 2006).

Within academic science, engineering, and medicine, substantial gender disparities exist. These range from the frequency with which men invite women to speak at conferences (Isbell, Young, and Harcourt 2012), how competent (Grunspan, Wiggins, and Goodreau 2014) and employable (Moss-Racusin et al. 2012) female students are perceived, the degree to which women and men self-cite (Symonds et al. 2006), how supported and inclusive a department feels (Fox, Deaney, and Wilson 2010), and the extent to which women feel they can make use of family-friendly policies even when they exist. Women are also more likely to hold teaching-intensive faculty positions over research-intensive ones, and so even when the national numbers appear to be increasing for the number of women in science, they are clustered in institutions where graduate students are not being trained, federal funding is less frequent, and in general are places where faculty receive less support to conduct independent work and contribute to the process of science (Hermanowicz 2012). And, even while the number of

women appears in recent years to be increasing in the sciences, the reality is that only white women are increasing in numbers, and women of color are on the decline (Armstrong and Jovanovic 2015).

While this is not the mission of this report, we note that gender discrimination itself harms women and the broader meritocracy of science. And thus we conclude that together, gender discrimination and male domination are features of the academic science, engineering, and medicine climate that create a permissive environment for sexual harassment.

SEXUAL HARASSMENT OF FACULTY AND STAFF

In the best meta-analysis to date on sexual harassment prevalence, Ilies and colleagues (2003) reveal that 58 percent of female academic faculty and staff experienced sexual harassment. In addition to the academic setting, the meta-analysis examines sexual harassment in private-sector, government, and military samples. When comparing the academic workplace with the other workplaces, the survey found that the academic workplace had the second highest rate, behind the military (69%). The government and private-sector samples were on par with each other with 43 percent and 46 percent, respectively. The top two workplaces (the military and academia) are both more male dominated than the private sector and the government, demonstrating the significance this has on rates of harassment, and also suggesting that in areas of academia that are more male dominated (such as engineering and specific science disciplines and specialties of medicine), the rates of sexually harassing behavior may be higher.

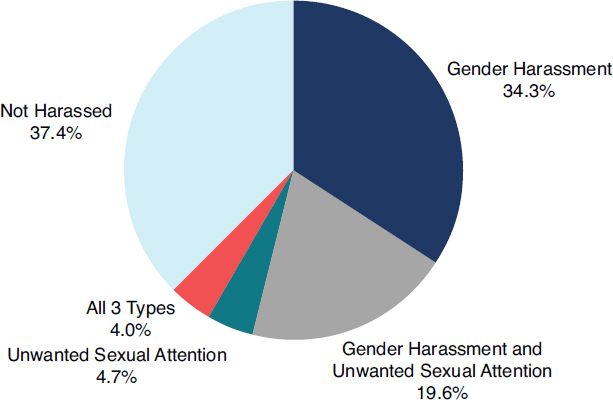

In a more recent study of analyzing the experiences of women and men working in academia, the court system, and the military, the connection to male-dominated workplaces was confirmed for academia. It demonstrated that even at a unit level when the underrepresentation of women increased one unit, the odds that women would face gender harassment (a type of sexual harassment) increased 1.2 times (Kabat-Farr and Cortina 2014). For female faculty and staff in academia, research has also confirmed the general finding from other workplaces that the majority of the sexual harassment experienced was gender harassment and that the other two types of sexual harassment were rarely experienced without gender harassment also occurring (see Figure 3-1) (Schneider, Swan, and Fitzgerald 1997). Rosenthal, Smidt, and Freyd (2016) documented that this pattern—gender harassment being far more prevalent that other types of sexual harassment—persists today. Their focus was the experiences of graduate students, who in many ways function as university employees. Their research found that “the majority of harassment experiences involved sexist or sexually offensive language, gestures, or pictures (59.1%), with 6.4% involving unwanted sexual attention, 4.7% involving unwanted touching, and 3.5% involving subtle or explicit bribes or threats” (370).

Also note that sexual harassment can be bottom-up, coming from those who

SOURCE: Adapted from Schneider, Swan, and Fitzgerald 1997.

have less formal power in the organization; researchers often refer to this as “contrapower harassment.” For instance, O’Connell and Korabik (2000) reported that 42 percent of their sample of women working in academia (as faculty, staff, or administrators) had encountered sexually harassing conduct from men at lower levels in the organizational hierarchy. Echoing many other studies, the majority of this subordinate-perpetrated harassment was gender harassment (e.g., insulting remarks about women, vulgar gestures, lewd jokes). Likewise, Grauerholz (1989) reported that 48 percent of women faculty at a large research university had encountered sexually harassing conduct from students; most commonly, this behavior entailed sexist comments (defined as “jokes or remarks that are stereotypical or derogatory to members of your sex”). Virtually all instances (99 percent) involved men as perpetrators. In one case, the student-on-faculty sexual harassment escalated to rape. To explain the dynamics underlying contrapower harassment, Grauerholz (1989) noted that “even in situations in which a woman has clearly defined authority, gender continues to be one of the most salient and powerful variables governing work relations.” This echoes Gutek and Morasch’s (1982) concept of “sex-role spillover,” which argues that gender-based norms (i.e., woman as maid, woman as nagging mother) seep into the workplace. In this way, contrapower sexual harassment reflects the lower status of women (especially women of color) in society relative to men, and it replicates that hierarchy in organizations (Rospenda, Richman, and Nawyn 1998). Moreover, in the academic context, students have a certain degree of power over faculty when

student evaluations influence promotion or reward decisions (e.g., Grauerholz 1989; Rospenda, Richman, and Nawyn 1998).

To gather a clearer picture of what the sexually harassing experiences were of women faculty in science, engineering, and medicine, our committee contracted RTI International to conduct a series of interviews with women who had experienced at least one sexually harassing behavior in the past 5 years (RTI 2018). When these women were asked to describe the most impactful experience, their responses varied, and included sexual advances, lewd jokes or comments, disparaging or critical comments related to competency, unwanted sexual touching, stalking, and sexual assault by a colleague. One respondent observed that most persons understood sexual harassment primarily in terms of unwanted sexual advances, but that gender-based harassment in academic settings was both widespread and impactful:

Most of them are demeaning the woman, shutting her up in the workplace, demeaning her in front of other colleagues, telling her that she’s not as capable as others are, or telling others that she’s not [as] sincere as you people are . . . I think more stress should be on that. It’s not just, you know, touching or making sexual advances, but it’s more of at the intellectual level. They try to mentally play those mind games, basically so that you wouldn’t be able to perform physically. (Assistant professor of engineering)

At the time of their interviews, most respondents characterized their experiences as sexual harassment. However, some respondents noted that they had not immediately recognized those experiences as such. Delayed awareness of sexual harassment was heavily influenced by the pervasive acceptance of gender-discriminatory behavior within the academic context. Many respondents reported that they were the only woman or one of a few women within their departments. Gender discrimination was often normalized in the male-dominated settings in which they worked, which interviewees believed had fueled sexually harassing behavior, fostered tolerance of it, and made differentiating it as such difficult.

SEXUAL HARASSMENT OF TRAINEES

In a recent effort to develop a campus climate survey for undergraduate students that could be used across institutions, researchers at RTI International (Krebs et al. 2016) conducted a nine-school pilot campus climate survey. The researchers focused on sexual assault primarily, and the survey questions on harassment were limited to crude sexual behavior and some forms of unwanted sexual attention (incidents of sexual assault were assessed separately from incidents of sexual harassment, and the sexist hostility component of sexual harassment was not assessed at all). The survey determined that the prevalence of female undergraduates who experienced crude behavior and nonassault forms of unwanted sexual attention in the 2014–2015 academic year ranged from 14 percent to as

high as 46 percent in some universities.6 The survey module did not include questions that would allow researchers to identify who the perpetrators were, and thus it is not clear whether the perpetrators were students, university staff, or faculty (Krebs et al. 2016).

In a second effort, starting in October 2014, Georgia State University convened a forum on campus sexual assault and harassment, which led to the development of the Administrator-Researcher Campus Climate Collaborative, referred to as ARC3, and which is led by Sarah L. Cook and Kevin Swartout from Georgia State University. Under the auspices of ARC3, a comprehensive survey instrument of sexual misconduct was developed with guidance from leading sexual violence researchers, student affairs and Title IX professionals, campus law enforcement, target/victim advocates, and counselors. The survey was developed for undergraduate and graduate students and included questions about the status of the perpetrator (faculty, staff, student, etc.). The ARC3 used state-of-the-art instruments based on the Sexual Experiences Questionnaire (SEQ) to ask behavior-based questions measuring sexual harassment, including all of its subtypes: gender harassment (broken down into sexist hostility and crude behavior), unwanted sexual attention, and sexual coercion (Swartout 2018).

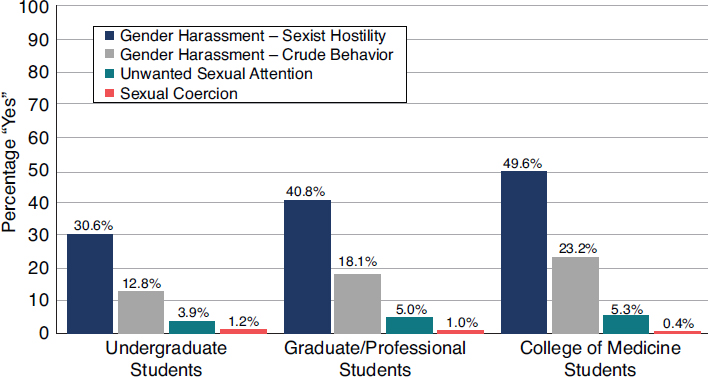

To date, 150 institutions of higher education have used the ARC3 survey to measure their campus climate.7 Two of those institutions, Penn State University and the University of Texas System, evaluated multiple campuses across their institution/in their system and thus included a large sample across multiple fields. The results show yet again that gender harassment is the most common form of sexual harassment and that women are sexually harassed more often than men. The overall rates of sexual harassment for students at these two institutions ranged between 20 and 50 percent depending on what level of education (undergraduate or graduate) they were in (Figure 3-3) and what the student’s major was (see Figure 3-2).

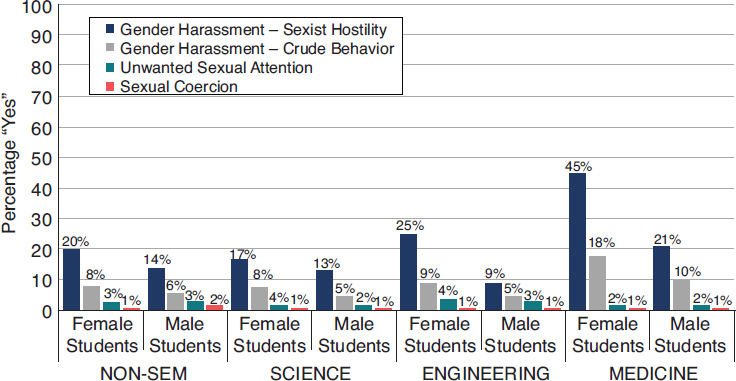

The findings from the ARC3 surveys are among the first to compare the sexual harassment experiences of women students in science, engineering, and medical fields to those of women in other fields (non-SEM). The surveys revealed that women in engineering and medicine faced more sexual harassment in the course of their studies than women in non-SEM majors or women in science majors.

For harassment perpetrated by faculty and staff, female medical students were 220 percent more likely than non-SEM majors to experience sexual harassment, while female engineering students were 34 percent more likely than non-SEM majors to experience it (see Figure 3-2). Interestingly, there was a significant difference in one type of sexual harassment the students experienced:

___________________

6 It is important to note that this rate is not a nationally representative estimate and should not be considered as one. The low rate is due to the selective definition of sexual harassment that does not include all three types of sexual harassment.

7 ARC3 leaders Sarah L. Cook and Kevin Swartout manage the survey and provide it to institutions looking to set it up for their campuses. See http://campusclimate.gsu.edu/contact-us/.

NOTE: The survey was given to 11,023 undergraduate students (2,945 responses), 4,000 graduate/professional (law) students (1,637 responses) at the University Park campus, and to 889 medical and graduate school students in the College of Medicine at the Hershey campus (411 responses).

crude harassment. Female medical students were 149 percent more likely than not in science, engineering, and medicine (non-SEM) majors to experience crude harassment by faculty or staff, while female engineering students experienced it at the same level as non-SEM and science students experienced it (8-9 percent, compared to 18 percent for female medical students) (see Figure 3-2). Almost half of women in medical school or enrolled as a graduate student in a college of medicine reported having experienced some form of sexual harassment (see Figures 3-2 and 3-3).

Using the ARC3 survey, Rosenthal, Smidt, and Freyd (2016) surveyed 525 graduate students regarding their exposure to sexual harassment and found that more than one-third (38 percent) of female graduate students experienced sexual harassment from faculty or staff, compared with only 23.4 percent of male graduate students. The study confirms that sexual harassment is common in higher education institutions and that female graduate students face higher rates of sexual harassment from faculty and staff compared with their male counterparts.

Sexual harassment can also be perpetrated by students on students. The Association of American University Women 2005 online survey, which used a non-SEQ set of behavior-based questions that left out sexist comments and focused on sexual behavior, found that 62 percent of all undergraduates had experienced sexual harassment. The research includes questions about the perpetrator, and the results showed that at college-related events and activities,8 peer harassment9 was significantly more common than harassment by faculty—80 percent of students who were harassed reported it was from peers or former peers and only 18 percent reported it was from faculty or staff (AAUW 2005).

While the ARC3 survey does measure peer harassment, we note that the ARC3 survey does not focus on any particular location when measuring experiences of sexual harassment. Respondents can report on student conduct occurring in any number of environments, both educational (e.g., classrooms, lectures, laboratories, libraries, patient rooms, surgical suites) and social (parties, bars, gyms, cafes, concerts, apartments, etc.). A major caveat of this measure is that it is not sensitive enough to distinguish harassing conduct (i.e., that which derogates, demeans, humiliates, etc.) from nonharassing, social-sexual behaviors from other students (e.g., sexual joking, flirting among friends). For example, if a female student reports that a fellow student distributed sexually suggestive materials or repeatedly asked her out on dates, there is no way to know whether this was upsetting versus humorous versus innocuous to her. Because of this blending of potentially offensive and inoffensive conduct, the result may be inflated prevalence estimates of student-on-student sexual harassment. For these reasons, the report

___________________

8 This was defined as when students are in classes, when they are in campus buildings (including student housing, libraries, athletic facilities, administrative buildings, etc.), when they are walking around campus, and when they are at school-sponsored events (including sporting events, campus organizations or clubs, campus fraternity or sorority events).

9 “Peers” refers to others at the same rank or level in the formal institutional hierarchy.

does not rely on the ARC3 student-on-student data, but we note that this is a form of sexual harassment that does occur in the education/learning/training settings.

SEXUAL HARASSMENT WITHIN THE SCIENCES

The following section describes studies that have examined sexual harassment experiences of women specifically in the sciences. A study conducted in 2015 (Clancy et al. 2017) of 474 astronomers and planetary scientists found that women who experienced sexist comments were much more likely to be trainees (students) at the time and slightly more likely to experience it from peers or others at the same rank or level in the formal institutional hierarchy than from superiors. Supporting other findings, the women in this study were more likely than the men to report experiencing sexual harassment.

The study also asked respondents about other forms of harassment including racial harassment and asked whether they felt unsafe in their position because of either their gender or race. The study found that women were more likely than men to report feeling unsafe because of their gender (30 percent of women respondents versus 2 percent of men respondents) and that respondents of color were more likely to report feeling unsafe because of their race (24 percent versus 1 percent of white respondents). Women of color were the most likely to experience verbal racial harassment (compared with men of color and white men and women), and that they were equally likely as white women to experience verbal sexual harassment. Additionally, women of color were most likely to report feeling unsafe compared with men of color, white women, or white men, and almost 1 in 2 women of color reported feeling unsafe because of their gender (40 percent based on gender and 28 percent based on race).

This study supports other research on women of color that shows women of color experience more harassment (as a combination of sexual and racial harassment) and thus are likely to be having more negative experiences than other groups (Clancy et al. 2017). Overall, this research adds to the growing evidence that white women and women of color in the astronomy and planetary science fields are experiencing sexual harassment at a level similar to other workplaces with similar environmental variables.

Field research is an important part of scientific scholarship, but it is also an environment that can present increased risks for sexual harassment. A survey of academic field experiences (the SAFE study) identified systemic and problematic behaviors in scientific field sites that may lead to a hostile environment (Clancy et al. 2014). The study identified several characteristics of field-site environments and the sexual harassment that occurs: (1) there was a lack of awareness regarding codes of conduct and sexual harassment policies, with few respondents being aware of available reporting mechanisms; (2) the targets of sexually harassing behavior in field sites were primarily women trainees; and (3) perpetrators varied between men and women—when women were harassed, perpetrators were pri-

marily senior to the trainees; however, when men were harassed, it was typically by a peer.

Clancy and colleagues (2014) used a snowball sampling technique to reach this diverse population of field scientists, and of those that responded, 64 percent (both men and women) had personally experienced sexual harassment in field sites in the form of inappropriate sexual remarks, comments about physical appearances or cognitive sex differences, or sexist or demeaning jokes, and more than 20 percent of respondents reported having personally experienced sexual assault. The research also found that harassment and assault at field sites were primarily targeted at trainees (students and postdocs), and specifically that 90 percent of the women who were harassed were trainees or employees when they were targeted at the field site. Significantly, the research found that in the field sites, women primarily experienced sexual harassment that came from someone superior to them in the field-site hierarchy.

This higher likelihood of the harassment being perpetrated by superiors is perhaps a unique characteristic that distinguishes research field sites from other workplace settings where it is more common for the harassment to come from peers. This characteristic of field sites is important in understanding the severity of the sexual harassment experienced because as the next chapter will show, the outcomes from sexual harassment can be worse if it comes from a superior who has power over the target.

In a 2017 follow-up, the SAFE team performed a thematic analysis of 26 interviews of women and men field scientists (Nelson et al. 2017). The first finding of this paper was that respondents had very different experiences of field sites where rules were absent, where they were present, and where they were present and enforced. That is, those field sites with high organizational tolerance for sexual harassment—field sites without rules, or those with rules but the rules were not enforced—were ones where respondents described sexual harassment and assault experiences. The second finding, that the scientists who were sexually harassed or experienced other incivilities had worse career experiences, also matches the broader workplace aggression literature. Finally, the authors found that egalitarian field sites were ones that set a positive example for scientists, had fewer incivilities, sexual harassment experiences, and sexual assault, and created positive experiences for respondents that reaffirmed their commitment to science. These data point a way forward, in the sense that organizational antecedents for sexual harassment in science work and education settings are similar to those of other workplaces, and that therefore the literature provides strong, evidence-based recommendations for reducing sexual harassment in science.

SEXUAL HARASSMENT WITHIN MEDICINE

The interviews conducted by RTI International revealed that unique settings such as medical residencies were described as breeding grounds for abusive be-

havior by superiors. Respondents expressed that this was largely because at this stage of the medical career, expectation of this behavior was widely accepted. The expectations of abusive, grueling conditions in training settings caused several respondents to view sexual harassment as a part of the continuum of what they were expected to endure. As one respondent noted, “But, the thing is about residency training is everyone is having human rights violations. So, it’s just like tolerable sexual harassment” (Nontenure-track faculty member in medicine) (RTI 2018).

With the exception of the ARC3 data from campuses with medical schools, unfortunately, much of the survey research conducted on the medical fields has not followed good practices for surveys on sexual harassment. As a result the prevalence numbers from these surveys on the medical field are not comparable and may be underreporting the rate of sexual harassment in these fields. One significant problem with comparing much of the data on the medical fields with other workplaces is the consistency of definitions used. In some, verbal harassment is separated out from the results of sexual harassment, and while they include verbal harassment in the form of sexist jokes as sexual harassment, they omit verbal harassment such as being called a derogatory name (Fnais et al. 2014; Fried et al. 2012). In other instances, the survey item that asks whether sexual harassment is occurring omits the crude behavior part of gender harassment (Jagsi et al. 2016), while some items combine and mix measures of sexual harassment with gender discrimination, resulting in the measurement of a much broader set of experiences (Baldwin, Daugherty, and Rowley 1996; Nora 2002; Frank et al. 2006).

Even so, the research can identify some characteristics of how sexual harassment occurs in medicine. In research that has examined different specialties in medicine, female surgeons and physicians in specialties that are historically male dominated are more likely to be harassed than those in other specialties, but only when they are in training. Once they are out of their residency and in practice they experience harassment at the same rates as other specialties (Frank, Brogan, and Schiffman 1998). These researchers suggested that for women in surgery and emergency medicine the higher rates of sexual harassment might be due to those fields having and valuing a hierarchical and authoritative workplace (1998). The preponderance of men in surgery and emergency medicine, and especially among leaders, is also likely a large factor in explaining the high harassment in these fields (Kabat-Farr and Cortina 2014). In two other studies, students perceived the experiences to be more common in the general surgery specialty than in others (Nora et al. 2002; Nora 1996), and other research reveals that respondents reported their perceptions of these harassing environments influenced their choice in specialty (Stratton et al. 2005). Other research suggests that sexual harassment may be worse depending on the medical setting; for instance, women perceived sexual harassment and gender discrimination to be more common in academic medical centers than in community hospitals and outpatient office settings (Nora et al. 2002).

One important finding from the research on the environment of academic medical centers is that in addition to students, trainees, and faculty being harassed by colleagues and those in leadership, they are also reporting harassment perpetrated by patients and patients’ families. The studies showing this also suggest that harassment from patients and patients’ families is very common and one of the top sources of the harassment they experience (Fnais et al. 2014; Phillips and Schneider 1993; Baldwin 1996; McNamara et al. 1995). This inappropriate behavior by patients and patients’ families needs to be recognized by leaders in academic medical centers, and specific statements and admonitions against sexual harassment should be included in the “Rights and Responsibilities” that are routinely presented to patients and families as they enter into both hospital and outpatient care in academic medical centers.

FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS

-

Academic science, engineering, and medicine exhibit at least four characteristics that create higher levels of risk for sexual harassment to occur:

- Male-dominated environment, with men in positions of power and authority.

- Organizational tolerance for sexually harassing behavior (e.g., failing to take complaints seriously, failing to sanction perpetrators, or failing to protect complainants from retaliation).

- Hierarchical and dependent relationships between faculty and their trainees (e.g., students, postdoctoral fellows, residents).

- Isolating environments (e.g., labs, field sites, and hospitals) in which faculty and trainees spend considerable time.

-

Sexual harassment is common in academic science, engineering, and medicine. Each type of sexual harassment occurs within academic science, engineering, and medicine at similar rates to other workplaces.

- Greater than 50 percent of women faculty and staff and 20–50 percent of women students encounter or experience sexually harassing conduct in academia.

- Women students in academic medicine experience more frequent gender harassment perpetrated by faculty/staff than women students in science and engineering.

- Women students/trainees encounter or experience sexual harassment perpetrated by faculty/staff and also by other students/trainees.

- Women faculty encounter or experience sexual harassment perpetrated by other faculty/staff and also by students/trainees.

- Women students, trainees, and faculty in academic medical centers experience sexual harassment by patients and patients’ families in addition to the harassment they experience from colleagues and those in leadership positions.

This page intentionally left blank.