Proceedings of a Workshop

WORKSHOP OVERVIEW1

Graduate medical education (GME) is critical to the career development of individual physicians, to the functioning of many teaching institutions, and to the production of our physician workforce. However, recent reports have called for substantial reform of GME (IOM, 2014; Weinstein, 2011). The 2014 Institute of Medicine (IOM) consensus report Graduate Medical Education That Meets the Nation’s Health Needs offered recommendations intended to strengthen GME, but also highlighted concerns about the paucity of GME outcomes data (IOM, 2014), noting that concerns about GME are difficult to address without reliable, systematic data. The current lack of established GME outcome measures limits our ability to assess the impact of individual graduates, the performance of residency programs and teaching institutions, and the collective contribution of GME graduates to the physician workforce.

Much of GME is based on tradition, regulatory requirements, and hospitals’ care delivery needs rather than on evidence of effective education (IOM, 2014). Systematic data collection and analysis could help to improve the quality and efficiency of physician training, which is a key element in

___________________

1 The planning committee’s role was limited to planning the workshop, and the Proceedings of a Workshop was prepared by the workshop rapporteurs as a factual summary of what occurred at the workshop. Statements, recommendations, and opinions expressed are those of individual presenters and participants, and are not necessarily endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, and they should not be construed as reflecting any group consensus.

improving the health of our nation. If national outcome data were available, large-scale observational studies could generate hypotheses for further research and innovation.

However, Debra Weinstein from the Partners HealthCare System and chair of the workshop planning committee stressed that defining and implementing GME outcome measures necessitate careful consideration about which GME outcomes are relevant, as well as clarification about what is actually measurable (now or in the foreseeable future). In addition, she said that the methods for data collection and analysis need to be considered, along with who should be responsible for tracking GME outcomes and with whom the data should be shared. The expanding use of health information technology (IT) and availability of big data could also facilitate large-scale tracking of GME outcome measures.

To examine these opportunities and challenges in measuring and assessing GME outcomes, the Board on Health Care Services of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine held a workshop, Graduate Medical Education Outcomes and Metrics, on October 10–11, 2017, in Washington, DC.

Workshop participants discussed

- meaningful and measurable outcomes of GME;

- possible metrics that could be used to track these GME outcomes;

- possible mechanisms for collecting, collating, analyzing, and reporting these data; and

- further work to accomplish this ambitious goal.

These proceedings chronicle the presentations and discussions at the workshop. A broad range of views and ideas were presented. Box 1 highlights a number of suggestions from individual worshop participants to define and implement GME outcome measures. The workshop Statement of Task can be found in Appendix A, and the workshop agenda can be found in Appendix B. Speakers’ presentations (as PDF and video files) have been archived online.2

OPENING REMARKS: OPTIMIZING GME BY MEASURING OUTCOMES

Weinstein opened the workshop by articulating the overarching purpose of improving health by optimizing caregiver education. She noted that

___________________

2 See http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Activities/Workforce/GMEoutcomesandmetrics/2017-OCT-10.aspx (accessed December 13, 2017).

this goal applies across the health professions and across the continuum of professional development, though the current (initial) focus is on GME.

Weinstein acknowledged that important improvements in GME have been made in recent decades, including an evolution from an immersive, unplanned “learn-by-doing” approach to curriculum-based education; graduation by default to a more careful assessment based on defined competencies; and informal oversight to an expectation of more explicit supervision. Yet, much has not changed, she continued: GME is still tethered to inpatient care, and resident activities are still heavily influenced by the service needs of teaching institutions. Concerns have been raised that today’s GME graduates are not prepared adequately for independent practice, and that the mix of graduates is not fulfilling national physician workforce needs, Weinstein explained. In addition, questions about funding persist—both about whether it is sufficient and whether it is justified, she said. These concerns were front and center when the IOM convened a committee in 2012 to examine the governance and financing of GME, resulting in the consensus report Graduate Medical Education That Meets the Nation’s Health Needs (IOM, 2014).

Insights from the 2014 Consensus Report: Graduate Medical Education That Meets the Nation’s Health Needs

Weinstein described three important realizations stemming from that committee’s deliberations:

- There is no shared understanding of what GME should accomplish. Historically, the sole expectation has been that GME programs produce competent physicians. However, additional goals need to be considered, including fulfilling national physician workforce needs and producing graduates who will advance biomedical science and health care delivery. There may also be expectations related to training programs’ contributions to the community, not just by producing local practitioners, but through impact of the GME programs themselves on care delivery.

- GME has not functioned as a system. Ten thousand GME residency programs and hundreds of institutions that sponsor them function within a common set of rules, are governed by the same group of oversight organizations, are funded largely by the same mechanism, and share a fundamental purpose. However, residency programs and teaching institutions are largely independent actors without coordination.

- No mechanism exists for comprehensive, ongoing, and consistent assessment of whether GME is meeting its goals. Believing that

GME is successful is not good enough: We need evidence that indicates what is succeeding, where improvements are needed, and how to make those improvements.

Why Measure GME Outcomes, and What Is Needed?

Measuring GME outcomes is essential for research aimed at enhancing GME and is needed to guide public policy, Weinstein asserted. Data related to the 130,000 residents who are in training at any time should be harnessed to continuously improve that training, she continued. Measuring GME outcomes with common metrics is needed to determine best educational practices and to measure the success of innovative pilots, she concluded.

Weinstein described a path to achieving this vision by (1) defining the relevant outcomes of GME, (2) identifying a system for ongoing tracking of common metrics, and (3) sharing data to facilitate large-scale research that could enable evidence-based education. Large-scale research is needed (versus single-program or single-institution studies) to provide evidence that is convincing enough to overcome entrenched processes, in which hospitals depend on residents continuing to do what they do now, she said. Large-scale research will also be more effective at influencing GME policy and regulations, and hopefully in demonstrating a significant return on the public investment in GME. She emphasized the importance of engaging all relevant stakeholders in the health care sector, including hospitals and other health care providers, regulatory groups, funders, and policy makers.

Weinstein described how, initially, observational data can be used to explore the relationship between educational processes and outcomes for graduates. For example, does the amount of ambulatory time during training correlate with the type or location of practice that graduates choose? Do physicians who have a deep experience with simulation during residency have different clinical outcomes than those that do not? Prospective interventional studies could then be used to compare different approaches to GME as long as common metrics are in place to assess the outcomes.

Measuring GME outcomes presents a number of challenges, Weinstein noted. Administrative burden is a major concern, so data collection would need to be efficient and streamlined. Some worry that common metrics would lead to a loss of autonomy, where all teaching institutions would be expected to demonstrate similar outcomes for graduates. Rather, Weinstein suggested that national goals should be met collectively, without each residency program and teaching institution being expected to contribute to every goal of GME. Privacy issues relating to data regarding individual physicians, residency programs, and teaching institutions would need careful consideration; these issues are the focus of a workshop session. Funding

is a challenge because the data collection and analysis would require some investment. Moreover, many stakeholders are reluctant to tinker with the status quo based on concerns about potential loss of current GME funding if a residency program or teaching institution demonstrates suboptimal outcomes. She acknowledged the risk of misinterpretation or overinterpretation of data, and noted the importance of meaningful, high-quality data within a responsible GME outcome measurement system.

Why Now?

Despite the obstacles and challenges, the time to develop metrics to measure GME outcomes is now for several reasons, Weinstein asserted, including the following:

- GME could capitalize on rapid advances in health information technology, big data, and data science.

- With a surging interest among medical school and academic health center faculty in education research, there are people who are willing and able to undertake this work.

- A number of the oversight organizations are shifting their focus from process to outcomes, with a corresponding willingness to relax rules and requirements for purposes of research. (Recent multi-institution studies of resident duty hours and the Education Across the Continuum project in pediatrics are examples.)

- Perpetual threats to federal funding for GME (along with greater constraints on institutional funds available for education) increase the urgency to demonstrate return on investment for taxpayers and to identify ways to use educational funds most effectively.

GME OUTCOMES: WHAT MATTERS?

David Asch from Penn Medicine Center for Health Care Innovation asked what GME should do better and for which areas GME should be accountable. Panelists responded by discussing the need to focus on clinical outcomes, community outcomes, and improving value in health care. Panelists and workshop participants also discussed perceived and real barriers imposed by the number of available GME positions, GME accreditation, and funding streams.

Good clinical training is important and necessary for the delivery of high-quality medical care, but it is not sufficient, said Gail Wilensky from Project HOPE. She added that GME has achieved excellence in the technical training provided to clinicians, and maintaining the excellence for which the U.S. training programs are known is essential. Humayun Chaudhry

from the Federation of State Medical Boards agreed, saying that one constant from his travels through South America, Europe, Africa, and Asia is an admiration for the way in which the United States educates and trains doctors. However, he said that in the 21st century GME also needs to focus on clinical outcomes and improved patient health. To achieve good clinical outcomes, Wilensky stressed, graduates should understand and be responsive to the needs of an ethnically diverse population.

An overarching challenge to GME progress is an overemphasis on inputs and insufficient focus on the outcomes for graduates, Wilensky continued. Despite discourse about value-based care focused on quality and efficiency, she said little progress has been made on this front; thus, GME activities should focus more on patient outcomes. Measuring outcomes is complicated, but GME needs to rise to the challenge and figure out what can be traced back to the clinical community, she said.

Several participants acknowledged that a fundamental challenge of focusing on clinical outcomes is identifying the most meaningful outcome metrics. For example, Donald Brady from the Vanderbilt University Medical Center noted that patient outcomes can be measured at different time points, but the longer the time frame, the less likely the outcome is to be directly associated with a particular clinician or program. Wilensky said that both the outcome of the individual being trained and the outcome for the patient should be measured to improve GME. Asch added that a set of outcomes for GME is a necessary requirement for a system of accountability for GME, and together those outcomes should more broadly reflect GME’s role in health care.

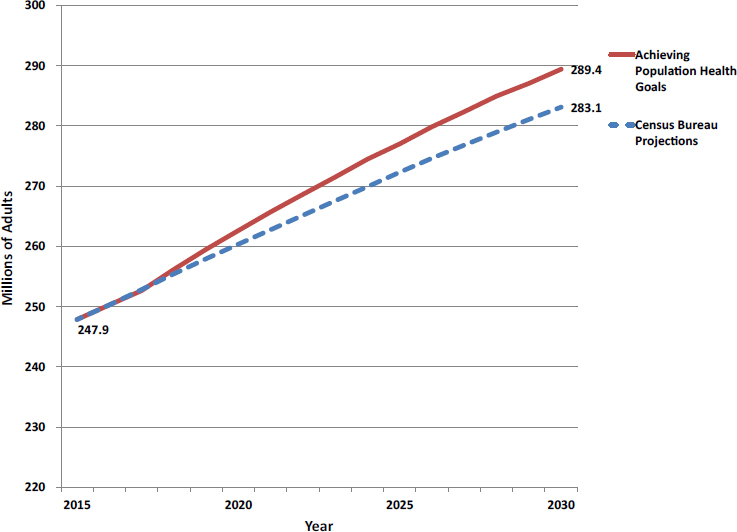

Fitzhugh Mullan from The George Washington University emphasized the need to focus on community outcomes in addition to individual clinical outcomes through more physician engagement in the community and programs to bridge the gaps in rural areas and in primary care. He said GME should consider its social mission beyond competencies and capabilities; the goal is not simply making GME better but also more equitable in the distribution of services that the graduates provide around the country. Advances in public health and medicine have contributed to dramatic increases in the average American life span in the past 100 years, from age 40 to age 70, but not without health disparities (CDC, 1999). The goal now should be to reduce the gaps in racial health disparities, and GME should be seen in that context, Mullan continued (Williams and Purdie-Vaughns, 2016).

Mullan stressed that physicians should play an important role in an “all hands on deck” effort to lift society as a whole. This means addressing social determinants of health and training mission-driven physicians, not just in family medicine, but also in other specialties, said Mullan. Currently, many health care training institutions are located in areas with significant poverty, but they often have little involvement in the community beyond

clinical care. GME could include an expectation of community engagement, defined in a variety of ways, with metrics measuring GME’s ultimate effect in the community, he said. One informative example is the concept of “communities of commitment” in undergraduate medical education, in which a medical school has a designated area in the community for which it takes some responsibility for making a measurable impact.

Although about 20 percent of the U.S. population lives in rural areas, less than 10 percent of physicians are in rural settings, said Mullan (IHS Markit, 2017). Residency is the staging ground for the workforce, where location, type, and style allegiances and values are formed. In some innovative GME approaches, teaching health centers address these workforce shortages by taking GME training to locations with physician deficits, but getting these programs off the ground is challenging. The current medical specialty mix does not represent U.S. health care needs, with 8,400 declared primary care shortages, Mullan added (IHS Markit, 2017). GME residency programs influence the specialty mix, but they are more focused on current hospital staffing needs than the national workforce needs. Addressing the social mission of GME would require metrics, data, and subsequent policy changes (CDC, 1999) for GME that are more accountable, responsible, and effective, Mullan stressed. Trying to separate GME from the entire remainder of what needs to be accomplished in health care would be a mistake, he concluded.

Mullan addressed the commonly raised issue of an upcoming GME shortfall—an insufficient number of GME positions for the number of medical school graduates. But Mullan said this notion is not supported by data. Each year, for the past two decades, more than 6,000 international medical graduates have undertaken GME training in the United States, meaning there have been about 6,000 excess GME slots (Mullan et al., 2015). However, the gap is closing; for the past 13 or 14 years, the number of U.S. medical school graduates entering residency programs has increased by about 2.4 percent annually (Mullan et al., 2015). Closing the gap could have a positive global impact, Mullan added, because currently the U.S. demand for international medical graduates is contributing to the brain drain in low- and middle-income countries, which is a destabilizing factor for those countries.

Marschall Runge from the University of Michigan introduced the concept of value-based outcomes, including a definition of value, as an important concept for GME programs. This has not been standardized across residency programs because of the challenge in measuring value. His comments focused on how to define and measure value in a meaningful way. What we want from GME is to optimize value in health care, said Runge. The term “value in health care” is broadly defined as a ratio of quality to cost. Our GME programs can and should embrace the goal that their

trainees graduate with the skill set and competency to practice and teach high-value health care at an appropriate cost, said Runge. To achieve this goal, residency programs should make value training a part of their common goals and learn from their collective experience, which has been the case for addressing so many different challenges over the past 20 years, Runge continued. At present, though, a focus on producing physicians who practice high-value health care across institutions is not commonly on the agenda for GME meetings.

Residency programs vary significantly, from academically oriented programs that include a goal of training practitioners across a broad spectrum of specialties, to physician scientists and others with unique expertise, to community-based programs that focus on training primary care physicians to serve the community. These are, and should be, very different programs with different training goals, but finding commonalities across these many programs in value-based health care could improve all residency programs, said Runge. As a simple example, physicians should have some familiarity with the kind of care that can be delivered in different settings as this can impact both the quality of care and the cost of care. He also proposed the concept of “precision education” to recognize that trainees start at different points and develop competency at different rates.

Emphasizing the importance of team-based care for improving value, Runge highlighted an example at the University of Michigan. He said the average cost to perform a joint replacement was $25,000, but Medicare reimbursement was $23,000. After bringing together a physician-led team that included experts in physical therapy, pharmacy, and home health, not only did they reduce the average cost to $19,000, but the length of inpatient stay and the use of opioids were both reduced significantly.3 Such pilots are important, said Runge, and they are likely scalable across institutions, but doing so involves collaboration, and a common denominator would be the orthopedic residents at each institution. Unfortunately, developing analogous processes for other specific causes of hospitalization often involves quite different factors. Ultimately, changing financial incentives can be leveraged to improve value, Runge also noted. In the past, many more physicians had loans repaid as an incentive to working in underserved areas. As a result of such loan repayment programs, about one quarter of these physicians remained in underserved areas.

Speaking to the challenges of measurement in GME, specifically measurement of value, Runge said the metrics currently required by regulatory agencies—payers and funders for GME—mostly fall into the category of being measurable, but not important. Despite this challenge, Runge offered some insights on strategies to measure value in GME. In terms of the most

___________________

3 See http://marcqi.org/about-marcqi/marcqi-goals (accessed January 9, 2018).

appropriate metrics available today at a very simplistic level, one possibility is to think about a way to measure how frequently trainees use evidence-based care guidelines, he said, noting that there are many good guidelines, but they are underused. He added that use of guidelines should consider the whole patient and allow for adjustments in care. A balanced approach to measuring use of physician guidelines could be a target metric of value. He also noted the recent rapid advances in artificial intelligence, and how that might change clinical practice and medical training in the future. The ability to analyze massive data sets would create new knowledge and may provide much more meaningful (albeit complex) metrics.

Another possibility might be to assess some aspects of training through feedback, said Runge, as he offered an example of investigators from Michigan using social media inputs from more than 40,000 residents across the United States to study depression and suicide in that population (Mata et al., 2016; Sen et al., 2010). The future is bright if we all are willing to innovate, take chances, and measure the success (or lack of it) for new interventions, said Runge.

Discussion of Challenges to Identifying, Measuring, and Achieving Optimal Outcomes

Several challenges to identifying, measuring, and achieving optimal GME outcomes were raised and discussed by the workshop participants. The panel had a robust discussion about whether the current requirements of residency programs are impeding progress in GME. Susan Skochelak from the American Medical Association (AMA) asked the panel whether requirements at the residency review committee level, including service obligations and location of training, which she said is often still limited to inpatient care, stifles innovation in GME. Mullan said that medical centers place a high priority on meeting accreditation standards and performing well in reviews by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME). Thus, they are hesitant to try new strategies or to highlight novel things they are doing, but instead focus on “checking all the boxes,” he said.

Thomas Nasca from ACGME responded, saying that the barriers discussed are perceived but not real. ACGME is not only willing to innovate by waiving standards, but has funded research on important questions, Nasca continued. There has been a dramatic change in perspective on GME accreditation over the past 15 years, not only with the introduction of the competencies and measurable clinical outcomes of education that could be linked to patient outcomes, but also in the standards, he said. Regarding the distribution of inpatient versus outpatient training, he said that two-thirds

of the training in internal medicine could be undertaken in the ambulatory care setting if desired, according to ACGME standards. He added that ACGME’s goal in accreditation is no longer satisfaction of minimum standards, but rather to help residency programs achieve excellence. ACGME cannot do it alone, however, and cannot be the only entity to set standards, said Nasca. Reflecting on Nasca’s comments, Runge added that the risk of innovation versus crossing the t’s and dotting the i’s has held back many institutions that are concerned about the balance between innovation and documentation of standards ACGME has historically followed. Thus, there is less innovation in education than is optimal. Dan Burke from the Morgan County Rural Training Track agreed with Nasca, saying that based on his experience in Colorado, ACGME standards have not been a barrier to innovation.

Burke also raised a funding issue. A real challenge is that funding goes directly to the hospitals even when the innovators are educators and scientists, he said. Changing who receives the money was a recommendation of the 2014 report, responded Wilensky, although little progress has been made in that regard. Many other participants, such as teaching health centers, are important and should also be able to receive the funding, Wilensky said. Another funding stream challenge discussed is where the funding is received within an institution. At many teaching hospitals, Medicare GME dollars flow to the hospital and are under the purview of the hospital chief financial officer, who has many financial needs and may not prioritize support for education, Runge said. At the very least, this important funding stream has been conflated and complicated based on individual institutions’ approaches to GME, Runge continued. Michigan Medicine recently developed a single unified budget that encompasses the medical school and health system specifically to be able to make funding sources and expenditures transparent and rational. Other institutions, such as the University of Pennsylvania, have made similar budgetary changes for the same reasons, having a common view of GME funds. This does provide additional funding that positions these institutions to be innovators in GME, he said.

CURRENT METRICS: WHAT IS MEASURED NOW?

National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME) Measurements

Peter Katsufrakis from NBME discussed four types of data that NBME collects to assess medical school students, including U.S. Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) performance data, NBME subject examinations, NBME clinical assessments, and data from exams that NBME also

administers for 15 health professional organizations.4 He concluded with lessons learned and a glimpse into future NBME data collection plans.

USMLE5 is made up of four elements, or four examinations in three steps, said Katsufrakis. Three of the four examinations include single best answer multiple-choice questions. Step 2 is divided into clinical knowledge (CK) and clinical skills (CS), with Step 2 CS consisting of 12 standardized patient stations, each of which lasts 15 minutes, followed by 10 minutes for the examinees to complete their postencounter note. Finally, Step 3 also includes clinical case simulations of managing a patient. To develop these examinations during any given year, more than 300 faculty members in various disciplines from medical schools across the country create items for the examinations, review the performance of items that have been created previously, and participate in the management and governance of the USMLE program.6 Although the USMLE’s primary purpose is as a licensing examination, most students consider it a residency placement examination because of the critical role USMLE scores play in the selection of candidates by residency programs. A significant number of medical students take USMLE exams, with approximately 40,000 examinees completing Step 1 and Step 2 CK, 35,000 students taking Step 2 CS, and nearly 30,000 students taking Step 3.7

Upon completion, examinees receive a detailed report of their scores, including performance gaps for which more focused training may be needed. Robert Phillips from the American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM) noted that at ABFM, residency training programs receive these competency reports and translate them into a personalized curriculum and education plan, an exercise that has been associated with significantly improved pass rates on the initial certification exam. In the coming year, Katsufrakis said the score reports would be presented in a new way to more clearly communicate examinees’ strengths and weaknesses in each subject area and relative to other examinees.

NBME also administers basic science and clinical science subject examination programs for students in medical schools, said Katsufrakis. In 2016, examinees took approximately 40,000 basic science subject exams.8 These numbers have declined in recent years as schools have opted for customized assessments. Five of the eight clinical subject exams, including medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics, psychiatry, and surgery are taken by nearly 25,000 examinees.9

___________________

4 See http://www.nbme.org/about/index.html (accessed December 18, 2017).

5 See http://www.usmle.org (accessed December 19, 2017).

6 See http://www.usmle.org (accessed January 9, 2018).

7 See http://www.usmle.org/performance-data/default.aspx (accessed January 9, 2018).

8 Unpublished data.

9 Unpublished data.

Nasca pointed out that one clinical subject, ambulatory care, had fewer than 1,000 examinees, well below other subjects. Katsufrakis said some of the challenges faced in graduate medical education are similar to those faced in undergraduate medical education. For example, it is easier to organize medical education around an inpatient facility in a hospital, and more challenging to manage an educational program in which students are placed in different locations across the city or perhaps across the state or region. The result, Katsufrakis continued, is more uptake for traditional internal medicine examinations that are focused primarily on content from an inpatient setting, compared with outpatient specialties, such as ambulatory medicine.

Katsufrakis described several challenges and barriers to using each of these data sets for research, including varied organizational policies and ownership rights, and data isolation. Different data policies govern release of USMLE data and NBME data because of shared ownership with the Federation of State Medical Boards, said Katsufrakis. Health professional organization exam data are potentially even more restricted due to differences in ownership rights and data management. These access challenges within NBME are an example of what to expect as methods to pull data from different sources are developed.

Because the exam systems were all developed separately, collating data for an individual’s performance on the different steps of the USMLE examination and the subject examinations is not simple, Katsufrakis said. However, NBME is reinventing its system to allow researchers to combine data from multiple examination sets by 2022. However, even then, NBME would face the challenge of matching data without universal identifiers, he said.

Katsufrakis used the example of the Data Commons10 to illustrate the challenge of creating and sustaining tools for research using these data. The Data Commons was formed by NBME and several other organizations to create a simplified way of combining data that were held by these different organizations for the purposes of research, said Katsufrakis. However, after expending hundreds of thousands of dollars to create the Data Commons, there was not much demand to use the system. He said the cautionary lesson from the Data Commons example is the need to consider regulatory and market forces as both carrots and sticks to promote use of future systems.

The Pediatric Milestone Assessment Collaborative

An encouraging example of successfully measuring a resident’s progress, said Katsufrakis, is the Pediatric Milestone Assessment Collaborative

___________________

10 See https://www.nbme.org/PDF/Publications/Examiner-2013-SpringSummer.pdf (accessed July 31, 2019). This link was revised after release.

(PMAC), a collaboration among NBME, the American Board of Pediatrics, and the Association of Pediatric Program Directors. PMAC’s mission is to “uphold the public trust by creating a unified, longitudinal approach to assessment of Pediatricians” that verifies continued competence beyond medical knowledge, drives continuous performance improvement, facilitates lifelong learning, and recognizes and guides both personal and professional growth. PMAC’s current focus is on developing assessments that can measure a pediatric resident’s progress through the milestones. Presenting results from PMAC, Katsufrakis noted that historically, achieving a generalizability coefficient (a statistical measure of the reliability of the assessments) in the range of 0.7 to 0.8 requires drawing data from 12 to 15 different observers (Donnon et al., 2014). Furthermore, by reducing the number of instruments from 12 to 6, the PMAC’s pilot studies were able to dramatically reduce the administrative burden of collecting data and improve information collection.11 All three PMAC modules will be completed within 24 months, he noted.

ACGME Milestone Data Measurements

Eric Holmboe from ACGME provided background on the learning curves and professional development of residents before presenting findings from ACGME’s Milestones12 project and next steps. GME’s goal is proficiency as defined by the Dreyfus model of professional development, as most graduates would not yet be experts, said Holmboe. Medical student graduates enter residency with only 12 to 20 weeks of experience in their discipline, climb the steep curve into proficiency within 3 to 7 years during residency, and then (hopefully) continue developing their expertise after residency and throughout practice (Pusic et al., 2014). Based on the current U.S. GME training model, Holmboe described how the five Dreyfus levels (Dreyfus and Dreyfus, 1980) of the ACGME milestones translate for residency programs, including (1) expectations for a beginning resident; (2) milestones for a resident who has advanced beyond entry but is performing at a lower level than what is expected at midresidency; (3) key developmental milestones midresidency and well into a specialty; (4) knowledge, skills, and attitudes for a graduating resident; and (5) exceeding expectations. Holmboe emphasized that the ultimate goal of residency programs is to achieve level four—ensuring that all residency graduates are prepared for unsupervised practice. Readiness for unsupervised practice in each subcompetency is not a requirement, Holmboe added, but a goal.

___________________

11 Unpublished data.

12 See http://www.acgme.org/What-We-Do/Accreditation/Milestones/Overview (accessed December 20, 2017).

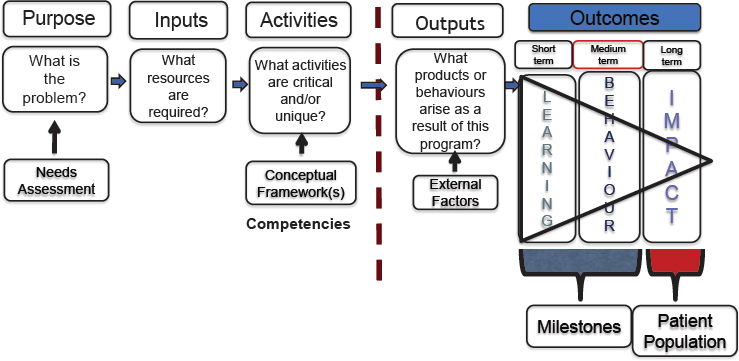

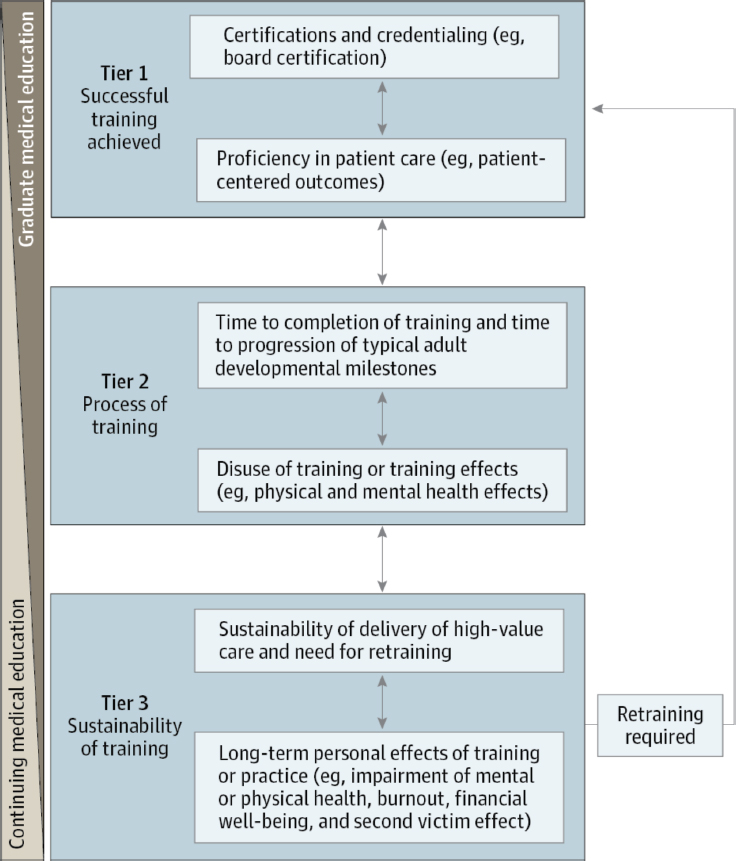

Holmboe also displayed a logic model to provide a conceptual framework that can be used to specify the goals of GME and to analyze how GME contributes to each goal (see Figure 1). The logic model provides the scaffolding that allows for the development of criteria for generating, selecting, and evaluating potential measures (see also Van Melle, 2016). It can be used to evaluate the purpose, resources needed (inputs), critical activities, and outcomes of a training program, he said.

ACGME’s Milestone project collects measurable outcome data for trainees in 144 specialties and subspecialties, said Holmboe (Hamstra et al., 2017). In June 2017, 133,335 residents and fellows entered the Milestone system, which generates 3.4 million data points every 6 months that can be used to analyze the performance of residents and programs (Hamstra et al., 2017). ACGME has generated evidence to demonstrate validity of the system, with national multi-institutional studies for internal medicine, emergency medicine, pediatrics, family medicine, and neurosurgery. Lawrence Smith from the Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell raised a question about the reliability of measurements, asking if an assessment from one program is comparable to another program, and recognizing that the evaluator’s frame of reference may also differ. Holmboe responded that the assessment framework between residency programs is a challenge and that researchers are trying to identify ways to improve Milestone assessments. He also added that some evaluators may not be fully trained on the competency elements they are assessing. Currently, it is “messy,” said Holmboe, but residency programs can use ACGME feedback

SOURCES: Holmboe Presentation, October 10, 2017; concept adapted from Van Melle, 2016.

data to help their faculty learn and adapt as a continuous quality improvement process.

Holmboe presented study results demonstrating how Milestone data are identifying gaps in the curriculum and providing evidence on the training trajectory that can help predict the likelihood of meeting level four proficiency targets. He said it can also help to identify workforce challenges, and longitudinal data would be used to assess how Milestones correlate with practice. For example, Holmboe said that in family medicine, residents are struggling with community medicine across the country, demonstrating that there is a likely deficit in the curriculum. These types of data can inform continuous quality improvement in training programs. Neurosurgery data analysis helped determine that a significant subset of residents were not meeting level four proficiency standards in Pain and Peripheral Nerve Surgery, and Surgical Treatment of Epilepsy and Movement Disorders. Reflecting on these data, the neurosurgery community realized these residents were likely not seeing enough patients to gain proficiency in their program for a number of reasons. These data helped to catalyze the neurosurgery community to revise their Milestones.

With multiple time points of assessment, Milestone data also allow ACGME to provide predictive feedback to residency training programs and to help identify residents with additional training needs. For example, Holmboe said ACGME recognized that progress slows for a subset of residents—a phenomenon called a plateau effect. Supplying this feedback metric to programs creates a potential opportunity for program leaders to provide an intervention for those residents.

Holmboe also provided an example of how ACGME is connecting with and using other longitudinal data, such as post-GME practice survey data. He said the Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors (AFMRD) implemented a survey of family medicine physicians, collected data on scope of practice, practice organization, preparation, and location, and had an excellent response rate. The AFMRD and ACGME team is hoping to conduct a longitudinal analysis connecting this survey data with Milestone data to potentially predict what happens when people enter practice. Thus, the Milestones data set is now reaching a level of maturity where it can begin to follow people out into practice, enabling correlation with Milestone data. These longitudinal studies are now possible because ACGME has longitudinal assessment data across all competencies, Holmboe concluded.

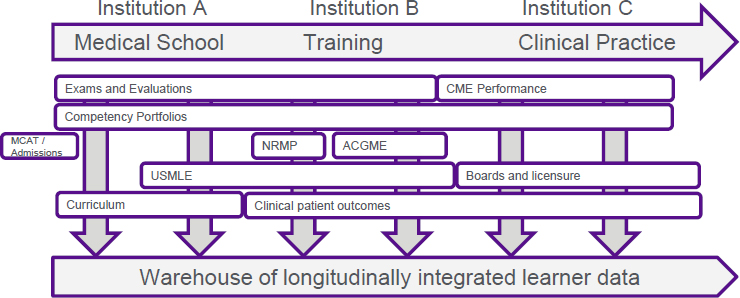

Edward Salsberg from The George Washington University Health Workforce Institute asked about the ability to share information in a national longitudinal database. The Milestones are co-branded, owned by both ACGME and the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS), Nasca responded, noting that they are working with LCME to provide Milestone data to medical schools for their graduates. Although data usage is limited

by the approvals, ACGME is currently engaged in discussions with the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education and ABMS about the opportunity for creating a blinded national database for individual data and perhaps also institutional data. The next big challenge is to integrate those data with clinical information, he said.

GME Program Metrics of the Health Resources & Services Administration

Nasca said the innovative programs of the Health Resources & Services Administration (HRSA) provide clues on how to decentralize GME and move into community settings, as he introduced Candice Chen of HRSA. Chen provided an overview of HRSA’s Bureau of Health Workforce Vision & Mission. She described GME payment and grant programs, including the metrics that HRSA uses to measure residency training program components and outcomes, as required by law.

HRSA is the agency within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) that focuses on ensuring high-quality health care for all communities, and particularly for underserved communities, said Chen. The HRSA Bureau of Health Workforce is key to achieving that mission. The Bureau supports stipends and other payment costs associated with GME through two types of programs: GME grants for preventive medicine residency programs, and GME payment programs, including the Children’s Hospital GME (CHGME) and Teaching Health Center GME (THCGME).

The statutory reporting requirements provide a sense of congressional interest in GME outcomes and metrics, said Chen (see Box 2). The Preventive Medicine Residency Program, which grants awards every 5 years and supported the training of 115 residents in academic year (AY) 2015–2016, was established after passage of the Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA) enacted in 1993.13 GPRA required all agencies to engage in strategic planning, performance planning, and reporting. The GPRA Modernization Act of 2010, more specifically, required program goals to be objective, quantifiable, and measurable.14 Under Title VII of the Public Health Service Act, HRSA’s National Center for Health Workforce Analysis is tasked with annually evaluating, developing, and publishing the performance measures for the Title VII programs, including the GME grants program, said Chen.15 Finally, HRSA’s Council on Graduate Medical Education is also tasked explicitly with developing, publishing, and

___________________

13 Public Law 103-162.

14 Public Law 111-352.

15 Section 761(b)(2) of the Public Health Service Act.

implementing performance measures for the Title VII programs, as well as developing longitudinal evaluations.16

Reporting requirements are operationalized through performance measures, said Chen. In AY 2015–2016, CHGME and THCGME programs

___________________

16 Section 762(a)(3)(4) of the Public Health Service Act.

provided annual reports on training program characteristics, including types of partners/consortia and total number of accredited and filled positions.17 They reported on individual-level characteristics of the residents they are training, including demographics, whether they are from a rural or disadvantaged background, training hours and encounters in primary care, underserved and/or rural settings, employment outcomes after 1 year, and intention at graduation. CHGME programs also report hospital information, including the hospital discharges by payer type, zip code, and patient safety initiatives within the hospital.

Chen discussed outcomes of the HRSA GME payment programs and discussed future program goals. One in two pediatric specialists were trained under the CHGME program, said Chen.18 In AY 2015–2016, children’s hospitals across the country trained more than 6,800 full-time equivalent residents, of which 4,600 were supported by the CHGME Payment Program. Furthermore, the CHGME program is currently supporting the training of about 48 percent of general pediatric residents and 53 percent of all pediatric subspecialty residents.19 Highlighting program successes, Chen noted that more than 60 percent of THCGME graduates are practicing in medically underserved communities and in rural settings.20

Looking forward, HRSA is focused on reducing the administrative burden of reporting for the grantees, improving accuracy of the training data, increasing visibility, connecting programs to other databases to longitudinally track graduates, and tying payments to metrics, said Chen. HRSA hopes to improve the quality of the data by developing a data collection portal that would allow trainees to self-report on metrics such as demographics, and to increase visibility of the program by connecting directly with trainees who may not know they are funded by HRSA. In the past year, THCGME and CHGME programs began using National Provider Identifiers21 (NPIs) in data reporting. Ultimately, connecting NPI numbers with Medicare and Medicaid claims would allow longitudinal tracking and insight into whether individuals trained in these GME programs continue to provide care for these critical populations, Chen said.

Finally, there is currently no mechanism to link funding to GME metrics, she said. However, in 2013, Congress authorized a Children’s Hospital

___________________

17 See https://bhw.hrsa.gov/grants/reportonyourgrant (accessed January 9, 2018).

18 See https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bhw/nchwa/childrens-hospital-highlights.pdf (accessed January 9, 2018).

19 See https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bhw/nchwa/childrens-hospital-highlights.pdf (accessed January 9, 2018).

20 See https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bhw/nchwa/teaching-health-center-graduate-highlights.pdf (accessed January 9, 2018).

21 See https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Administrative-Simplification/NationalProvIdentStand (accessed November 14, 2017).

Quality Bonus System, which HRSA will begin to implement in 2019.22 With this program, HRSA plans to address issues such as access, quality, and cost of care, as well as provider wellness.

Metrics of the American Board of Medical Specialties

Lois Margaret Nora from ABMS defined board certification, explained the process of certification and associated metrics, and discussed lessons learned and future trends in board certification assessments. ABMS23 is the umbrella organization for 24 independent member boards that oversee the standards through their assessment mechanisms in 39 specialties and 86 subspecialties, said Nora. The ABMS boards certify both allopathic and osteopathic physicians, and the American Osteopathic Association also certifies osteopathic physicians in the osteopathic medical specialties. ABMS board certification is distinct from medical licensure, which is a requirement for practicing medicine. Board certification credentials are grounded in the standards that define the specialty and are a statement that the physician meets the professionalism, knowledge, skills, and standards of the specialty board.

Initial board certification (which was the primary focus of this presentation) entails an ongoing assessment of knowledge, skills, and professionalism across an extended period of time, generally through completion of training in an ACGME-accredited residency or fellowship program, said Nora. Board certification requires a statement from the ACGME program director regarding the professionalism, ethical behavior, and readiness for independent practice of the trainees, in addition to successful performance on board-based assessment. Other requirements vary by board and may include oral examinations, practice requirements, professional recommendations from peers and hospital leadership, procedural case log books, hospital privileges, and elements of certification(s) examination administered during residency.

Providing evidence that board certification makes a difference, Nora cited research showing that patient outcomes across a wide variety of clinical conditions are better when care is provided by an ABMS board-certified physician (Hawkins et al., 2013; Sharp et al., 2002). There are also fewer disciplinary actions for board-certified physicians (Lipner et al., 2013). Board certification is an important distinguishing factor in clinical privilege and has been identified as important to patients and their families, Nora added.

___________________

22 See https://bhw.hrsa.gov/fundingopportunities/default.aspx?id=fa87b0b7-3538-43f4-af1d-55e3ba2f464b (accessed January 9, 2018).

23 See http://www.abms.org (accessed December, 19, 2017).

Nora highlighted current trends and lessons learned. First, ABMS is working to address the limited understanding of board certification among medical students. One lesson learned from a board that dropped oral examinations for a period of time is that they provide unique information regarding skills such as clinical reasoning and ethical analysis (personal communication from Robert H. Miller, American Board of Otolaryngology, 2017). Use of technology and simulation-style assessment is increasing, and all boards are looking at how to use the Milestones and better understand what information the Milestone system can provide. Looking forward, Nora noted three fundamental questions to address regarding board metrics: (1) What measures give us the most important information? (2) What measures give us unique information? and (3) What do measures say about length and style of training?

Several participants discussed the importance of applying board certification and other assessments of GME in practice. Several strategies to assess metrics throughout the career of a physician are being evaluated by some boards, such as registries and long-term Milestones, that could potentially provide important information back to GME educators, said Nora. However, GME is a relatively short time period compared to the career of a physician, so it is important to also consider how lessons learned from GME apply across the career of a physician. Nora provided an example of how the American Board of Urology (ABU) used data to reduce unnecessary patient testing and improve patient care (Pearle, 2013). ABU evaluates practice based on longitudinal Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code data and noted, a number of years ago, that there were certain practices that were duplicative and redundant (e.g., urinalyses and urine creatinine tests). Through questions, discussion, and education from ABU, that trend changed and patient care was improved by reducing unnecessary testing, said Nora.

Certifying boards can play a helpful role in residency training and then look at different time points in practice to see how training is reflected in care quality and patient outcomes, added Phillips from ABFM. ABFM worked with the AFMRD to develop a survey of their graduates who are 3 years out of training. This survey provides feedback to residency programs about how prepared their graduates thought they were for practice, and what they are doing in practice. The Family Medicine Review Committee requires surveys of graduates, but Phillips said that this has not been done rigorously in the past; the ABFM–AFMRD partnership provides greater standardization through their survey, which had a 67 percent response rate in its first year. Katsufrakis said that perhaps the greatest value of this survey approach might be to provide feedback to individuals in clinical practice about how they could improve. Nora added that one of the most remarkable things happening within the board community, relative

to continuing certification, is the uptake of longitudinal assessments. The results of these assessments feed into a system that could provide summative conclusions, and thus allow for substantial modifications to improve the high-stakes decadal exam for maintenance of certification (MOC).

BLUE SKY: DATA IN THE FUTURE

A panel of data scientists and health services researchers presented data they have collected and analyzed in their fields, and discussed potential implications for future GME research.

Lessons from Measuring Provider Performance in Clinical Practice

Rachel Werner from the University of Pennsylvania spoke about measuring provider performance in clinical practice, and the implications for GME. Werner first described the qualities of good performance metrics, which she said should be correlated with something important. In the patient care setting, that often means clinical outcomes. The reason to focus on measurement is to improve quality of care; thus, quality metrics are only useful to the extent that providers can control what is being measured and thus have the opportunity to improve that quality. Furthermore, quality metrics should not unintentionally harm clinical care. A big challenge of measuring quality in any setting is ensuring that the data are current, and that the measures are relevant and important, Werner added.

Process measures, which assess whether the right care is delivered and whether care is concordant with clinical guidelines when they are available, have been very widely adopted across clinical quality measurement activities for a number of reasons, said Werner. Process measures are directly under the control of the providers and are less sensitive to the clinical and sociodemographic characteristics of patients. Process metrics are also measured in the short term, giving providers immediate feedback about the quality of care they are delivering and thus providing clinicians with the opportunity to change practice to improve quality of care. However, there is a need to validate these measures, which are surrogate outcomes, to ensure that they are related to patient outcomes.

Too often, process measures are not well correlated, at least at a provider level, with patient outcomes, said Werner. For example, when Medicare began rating hospitals on the quality of care they delivered, they did so using a series of process measures (Werner and Bradlow, 2006). For heart attack patients, Medicare used five measures (aspirin on admission, beta-blocker on admission, aspirin on discharge, beta-blocker on discharge, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor for left ventricular dysfunction) (Werner and Bradlow, 2006). However, although process-based

performance improved, the mortality trend did not change significantly (Ryan et al., 2012). Similarly, in a Medicare demonstration project, reimbursement for a small group of hospitals was partly determined by process metrics for heart attacks, but data showed that although process-based quality improved in participating hospitals, patient mortality at 30 days remained unchanged (Werner et al., 2011).

Measuring clinical outcomes directly is appealing both to policy makers and to patients because outcomes are clinically meaningful end points and have strong face validity, said Werner. However, she emphasized the importance of ensuring that provider-level outcomes are (1) valid measures by ensuring they truly reflect provider quality, as many factors influence patient outcomes and are not simply a measure of patient risk; and (2) under the provider’s control. Werner provided several examples of research results in which improved patient outcomes were linked to provider quality rather than patient characteristics. In one study, researchers investigated whether hip fracture mortality at a hospital was predictive of that hospital’s future outcome. Results indicated that hospitals with lower mortality for hip fracture patients in the past did much better with current hip fracture patients, indicating that the outcome was a result of hospital quality (Neuman et al., 2016). Another study demonstrated how researchers can use comparisons among the same set of patients to control for patient risk. Analyzing data from patients who were admitted to multiple hospitals within a relatively short period of time, researchers found that readmission rates at the historically higher-performing hospitals (hospitals with low readmission rates) were 2 percent lower than readmission rates at historically lower-performing hospitals (hospitals with higher readmission rates). Thus, this research provides evidence that providers’ past outcomes predict future outcomes, even after controlling for patient risk (Krumholz et al., 2017). In a third study, researchers used Medicare data to examine readmission rates for a group of conditions across all hospitals in the United States and found a significant reduction in readmission rates across hospitals with a focus on those conditions, said Werner (Zuckerman et al., 2016). This study demonstrated that outcomes are under provider control; in other words, hospitals can improve their outcomes.

Werner also emphasized the importance of monitoring for unintended effects of assessing quality metrics. Although quality metrics are always well meaning, the ways in which providers react to them or the ways in which care delivery changes in response to metrics can be surprising, said Werner. One risk to patients could result from “cream-skimming,” in which risk adjustment of patient outcomes is imperfect because providers treat patients who appear healthier, intending to maintain a high-quality rating on these outcome metrics, Werner continued. Because the patients receiving treatment are healthier to begin with, there is an appearance of improved

patient outcomes without true improvements in the quality of care provided (Konetzka et al., 2013; Werner et al., 2005). Thus, it is essential to construct metrics in a way that minimizes this bias.

In closing, Werner articulated lessons that could translate from clinical quality measurement to GME. First, data and methods for using patient outcomes to evaluate GME training programs are available; thus, using metrics based on patient outcomes is possible, although monitoring unintended consequences is a challenge. However, questions remain about whether patient outcomes occur over a time period that is short enough to make outcome-based metrics a feasible strategy to measure and improve GME. Finally, she said that leveraging policy and funding opportunities to identify ways to improve clinical quality measurement and influence provider behavior could benefit GME as well.

Linking Data Sources to Inform GME

Anupam Jena from Harvard Medical School provided several examples of research demonstrating how claims data, which includes physician NPIs, can be linked with other databases to better understand the characteristics of physicians who deliver high-quality care. The key is to take patient data that are already routinely collected, include information on the various providers that interact with each patient in the hospital, and then link that to information about those providers, said Jena. Data sources include claims data for Medicare or other major insurers, state inpatient data, Optum Labs,24 and Doximity,25 a medical professional network with detailed physician information.

In one study assessing the impact of resident duty hour reform on patients, researchers used Florida state inpatient data to compare patient mortality rates between newly practicing physicians who trained before versus after duty hour reform, using physicians who were 10 years out in practice as a control group. Results indicated that reductions in mortality were unrelated to duty hour reform, but rather to secular changes in hospital care (Jena et al., 2014). In another study evaluating how patient outcomes change with years of physician experience after residency, researchers linked Medicare claims data with Doximity data and found that hospital mortality increased with each year after internal medicine residency completion (Tsugawa et al., 2017). The opposite was true, however, in a similar unpublished study of surgeons, implying that a surgeon’s years of experience correlated with improved patient outcomes.26 To control for

___________________

24 See https://www.optumlabs.com (accessed December 20, 2017).

25 See https://www.doximity.com (accessed December 20, 2017).

26 Unpublished data.

selection bias in each of these studies, researchers studied hospitalist physicians and emergency weekend surgeries, both situations in which patients do not choose their physicians, and vice versa.

Jena emphasized the potential implications for using this type of research in accreditation and recertification. Assessing residency programs and medical schools on the basis of patient outcomes rather than processes is a useful avenue to consider, but there are challenges, he said. One challenge is determining whether the patient outcomes are due to residency training or to the types of doctors who choose particular residency programs. Werner had previously raised this concern, stating that a challenge for GME metrics includes separating selection effects from training effects, as high-performing physicians may cluster at particular programs. To address this question, Jena suggested using residency match data to study individuals at the cutoff between two residency programs, at which point the program they were admitted to was close to randomization, said Jena. Similarly, pairwise comparisons could be used together with linked residency match data and patient outcomes data to get a causal estimate of the impact of a particular training program on the long-term outcomes of patients who are treated by that program’s graduates, Jena continued.

A participant from Massachusetts General Hospital asked about strategies to account for the fact that multiple people provide care for patients. Jena answered that at the end of the day, even in team-based medicine, the attending physician always has primary responsibility. It is possible to see which other physicians are involved through claims data. Even with the involvement of students and nurses, whose data are not captured in claims data, one physician is responsible for the patient’s care, and that physician is billing Medicare (or other insurers) for the care.

Jena also provided examples of quality assessment using prescription data instead of mortality data. Researchers have demonstrated that within the same emergency department, the likelihood of a patient being prescribed an opioid by an emergency physician varies by nearly threefold across physicians (Barnett et al., 2017). Following these patients for 1 year after the original emergency department visit showed that patients who happened by chance to see a high-intensity opioid prescriber were 20 to 30 percent more likely to become a long-term user of prescription opioids, compared with patients treated by a low-intensity opioid prescriber (Barnett et al., 2017). Data on opioid prescribing can also be linked to Doximity data to see whether physicians training in specific residency programs or medical schools are more likely to prescribe opioids. The implication for GME is that specific programs could be identified with the goal of targeted educational interventions, which could subsequently be evaluated using similar data.

The keys, Jena emphasized, are obtaining support from organizations that hold necessary data to study questions related to GME outcomes,

linking multiple data sources, conducting robust empirical assessments that rely on quasi-experimental research strategies, and obtaining funding to conduct this research. He also stressed the need to train future researchers in these methods, and the importance of funding data acquisition and research methods.

Using Clinical Data for GME

Alvin Rajkomar from Google Brain and the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), presented a series of studies he conducted at UCSF using both administrative and clinical data to guide how residents practice. He shared his thoughts on the kind of data to expect in the future. In his first study, Rajkomar created a program to analyze clinical notes in electronic health records (EHRs) to ascertain which diagnoses residents commonly see or rarely encounter (Rajkomar et al., 2017). In another study, Rajkomar wrote a program to provide interns with a list of patients for whom they had written notes while on rotation at UCSF to enable residents to follow their patients’ progress. This exercise showed that interns greatly valued the data, and he found that even when the interns had the wrong diagnosis, they learned from that, said Rajkomar. Some interns also noted moments of vindication where they had made the correct assessment. Finally, upon reading their own discharge summaries, interns realized how confusing some of their summaries were and subsequently improved on them (Narayana et al., 2017).

In a third study, Rajkomar emphasized that providing data feedback is not a trivial or simple exercise, and utility matters. He created a program that gave residents daily feedback on their identified quality improvement (QI) performance. In a randomized controlled trial, Rajkomar found this daily feedback on QI performance did increase resident performance; however, the residents disliked the feedback because they found it redundant (Patel et al., 2016). Rajkomar noted two other important lessons learned from these experiments. One is that attribution matters. Interns write notes, so finding their data is easier than it is for residents, whose contributions may not be reflected in the EHR. The second important lesson learned is that accuracy matters. If data are inaccurate for even a single patient, it is hard to win back the trust of the clinicians.

Future data will not come from clinicians entering data, said Rajkomar, but technology is going to capture the data that are generated in the course of clinical practice. For example, some hospitals are trying to collect data via Amazon’s Alexa27 or other kinds of voice dictation or assistants to document the clinical encounter (Singer, 2017). Other studies of “click

___________________

27 See https://developer.amazon.com/alexa (accessed December 20, 2017).

logs” that track what users are clicking on in the EHR could also provide valuable data (Arndt et al., 2017). Rajkomar also described a study using police body camera footage to understand how police officers are communicating with citizens, and noted that it just takes a small leap of logic to think about using this technology to assess communication between residents and patients, although it could become invasive (Voigt et al., 2017). In conclusion, Rajkomar stressed that it is imperative to use the data responsibly and reiterated the importance of having trainees access and analyze their own data in the future. Despite variations in resources in training programs, technologies to help trainees become better physicians should be democratized for all trainees, he added.

GME METRICS

Workshop participants divided into four breakout groups to discuss metrics that could be used to advance GME at four levels: (1) GME graduate level, (2) GME residency program level, (3) teaching institution level, and (4) regional and national levels (see Box 3).

GME Graduate-Level Metrics

Kelly Caverzagie from the University of Nebraska and Bridget McIlwee from ProPath and ACGME presented the top three metrics identified by the graduate-level metrics breakout group, with a focus on measuring outcomes expected of GME graduates. The first is competence, said Caverzagie, which could include individual performance, especially for procedural specialties, as well as team-based care and population management. A strength of this metric would be its orientation toward meeting public and professional expectations, but the metric is limited by the availability of valid assessment tools and the variability of standards across specialty boards, he noted.

Caverzagie said the second metric focuses on value of care (patient outcomes per cost of care) from the perspectives of both the public and the profession. The strength of value metrics is their focus on patient care. Value metrics would measure the actual care provided by graduates after they leave the residency or the fellowship program. A limitation is the difficulty in standardizing the assessment of a value-based outcome, said Caverzagie. Choosing Wisely28 could be used as a starting point for value metrics, Caverzagie added.

The third metric is professional engagement, said Caverzagie. A residency program fostering professional engagement puts the learner in an environment in which he or she can continue to evolve, grow, and engage

___________________

28 See http://www.choosingwisely.org (accessed November 14, 2017).

with the profession. Validated survey instruments exist to measure professional engagement and burnout, which are two sides of the same coin, he said. Taking into account the pressures of residency with an emphasis on clinician well-being is an important step to prevent and mitigate burnout, said McIlwee. When residents are burned out and choose in the end not to

practice, that reflects on the GME program’s value. The group discussed the possibility of creating a composite score of engagement and burnout to take both components into account. Several participants noted that challenges with measuring professional engagement include understanding what it means over the long term, parsing out all of the confounders of professional engagement, and tracing this metric back to the residency program.

GME Residency Program-Level Metrics

Furman McDonald from the American Board of Internal Medicine and Christina Al Malouf from Pennsylvania Hospital presented the top four metrics discussed during the GME residency program-level breakout discussion. The first category was workforce metrics that could be assessed at the institutional, regional, and national levels, said McDonald. Workforce measures connect to the societal need of training doctors. However, workforce metrics are challenging because residency program directors have limited ability to change GME to address workforce needs. Other challenges include a lack of clarity on how to define workforce needs, and the time lag between initial training and meeting workforce needs, he said.

The second focus was the quality of care delivered by the graduates of the residency program, said McDonald. Al Malouf added that this should include resident confidence and autonomy, as well as an aggregation of individual quality measures associated with a physician. Quality of care metrics have strong face validity and would be useful for public accountability but are limited by a lack of agreement on the definition of this metric. Furthermore, given the heterogeneity of quality metrics and patient populations, such assessments would require risk adjustment methodology, McDonald added.

Many group participants suggested specialty board certification rates as a third metric, which are already used in practice as a metric across most residency programs, said McDonald. Strengths of this metric include public accountability, easy measurability, availability, and connection to many other metrics of good care. The limitations of using board certification rate as a metric include variability across boards, lack of board certification for some specialties, and that board certification is a floor measurement, measuring basic competence, rather than a ceiling measurement of a program’s aspirational competence, he explained.

The fourth category of suggested residency program metrics was internal process measures, said McDonald, including the clinical learning environment, graduate data, professionalism measures, and patient outcome data. The strength of internal process measures is their ability to serve as a foundation for all the other metrics. McDonald emphasized the need for ACGME to benchmark internal process measures, moving toward

community standards. Al Malouf added that from a trainee perspective, such metrics should also include resident well-being. Limitations, however, include the subjectivity of some measures as well as the lack of standardization across institutions, he concluded.

Teaching Institution Metrics

Monica Lypson from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and McKinley Glover from Massachusetts General Hospital presented five categories of teaching institution metrics discussed by the teaching institution–level breakout group, including graduate outcomes, communities of commitment, clinical learning environments, value, and evaluations for program accreditation. Marschall Runge of the University of Michigan previously explained that communities of commitment indicate an institution’s explicit declaration of commitment and responsibility for a specific area.

Regarding graduate outcome metrics at teaching institutions, Glover echoed previous comments, emphasizing a focus on graduate distribution metrics to meet workforce needs, including practicing in areas with a shortage of health professionals, and proportionately adjusting the distribution of trainees among needed specialties and subspecialties. He said another key metric is output of graduates, including their contribution to discovery science, community service, patient care, and so forth. Other key metrics include the quality and success of the training environment measured by the number of trainees who transfer across specialties, those who take additional years to complete their training, and drop-out rates, he continued. Additional important metrics include board certification rates and MOC. The strength of reporting these metrics, said Glover, includes implications for the public, especially because the residency programs are publicly funded. Graduate distribution and workforce metrics would necessitate reporting mechanisms that explicitly address needs in research, social health equity, and primary care. Glover and Lypson also discussed the potential unintended uses of such data as a challenge. Glover also emphasized the importance of process and outcome measures relating to the clinical learning environment, including evaluation of curriculum, knowledge of patient safety, and trainee outcomes in practice. However, creating a platform for these metrics could be a challenge, he said.

Finally, Lypson discussed the possibility of using currently available data, including the health care index (data sets covering changes in medical costs, employment, and education),29 and data on the last 6 months of life

___________________

29 See https://www.usnews.com/news/health-care-index/articles/2015/05/07/the-methodology-behind-the-us-news-health-care-index (accessed February, 8, 2018).

to measure value. The strengths of this approach are that data are available, and the metric is not specialty specific and reflects meaningful patient outcomes and cost. However, hospital culture may limit use of such value metrics, she said. Lypson also discussed the potential use of data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Merit-Based Incentive Payment System30 to drill down to the provider level. However, a challenge is linking to resident outcomes, Lypson noted.

National-, Regional-, or State-Level Metrics

John Norcini from the Foundation for Advancement of International Medical Education and Research and Jordan Warchol from The George Washington University addressed the topic of national-, regional-, and state-level metrics by presenting metrics that their breakout group suggested for four primary stakeholders, including self-regulators, such as boards and specialty societies, state and federal policy makers, patients, and trainees.

For self-regulators, Norcini and Warchol described five metrics, including board certification, patient outcomes, physician joy in practice, physician sociobehavioral skills, and professionalism and disciplinary action. Board certification shows breadth and depth of specialty and is a known standard, but it is limited in that it is knowledge heavy. They also noted that questions have been raised about the relevance and validity of MOC. Patient outcome metrics, as noted previously, are important to improve patient care and physician practice but are limited in GME assessment because of uncertainties concerning the appropriate timing and specific measurements. Metrics that assess joy in practice could lead to improved clinician well-being and thus improved patient outcomes, but it may be hard to modify and, because of its multifactorial nature, a challenge to measure. Most important to patients, Warchol argued, is physician sociobehavioral skills, which include team-based care, coordination of care, communication skills, partnering with patients, and understanding social determinants of health. However, challenges to such metrics include questions about validity, subjectivity, and expense. Finally, measuring professionalism and disciplinary actions could be important to protect patients. However, using these metrics appropriately is a challenge due to variability of sanctions across states, said Warchol.

For state and federal policy makers, the breakout group focused on metrics that could assess return on investment, including geographic distribution, specialty distribution, and provision of care to underserved populations after training, Warchol explained. Data are available to assess both geographic and specialty distribution metrics, but there are questions about

___________________

30 See https://qpp.cms.gov (accessed February 8, 2018).

whether the necessary clinical infrastructure is available where physicians are needed, or whether funding could incentivize physicians to move. Warchol added that requirements to provide care for underserved populations or to report related data are currently lacking.

Warchol discussed three metrics for patients: clinical outcomes, patient experience, and access to providers. Clinical outcome metrics may be challenging for patients to use if the personal relevance of the data is unclear. Patient experience metrics, on the other hand, which she said could be collected through programs such as Truth Point,31 may have limited utility if there is a lag time, or if all representative patient voices are not heard. Finally, Warchol identified access to providers as a key metric but noted the challenge of using the data to address gaps in a timely manner.

For trainees entering residency, understanding program characteristics, such as where graduates go and what they do (e.g., academics, community practice, caring for underserved populations) after training, is important. Warchol noted that assigning each trainee an NPI number could be beneficial in tracking this metric. Furthermore, she said that resident assessment of training is a critical metric for trainees, including whether the residents feel both confident and competent upon graduation, and whether they would choose their program again. Such data would provide a good assessment of the residency programs on a national level, but are limited by their inherent subjectivity, Warchol said.

CAN OUTCOME MEASUREMENT PROVIDE A PATH TOWARD EVIDENCE-BASED EDUCATION?

In discussing how outcome measurements could guide evidence-based education going forward, panelists provided examples of how they are using or could use data to modify their curricula, create innovative educational programs, and guide and assess how residency programs are meeting society’s medical workforce needs.

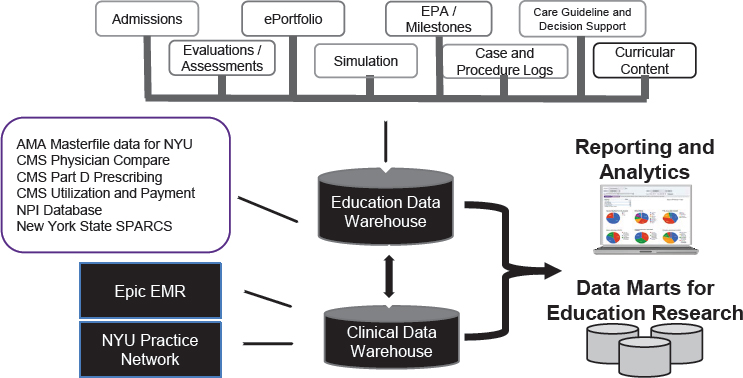

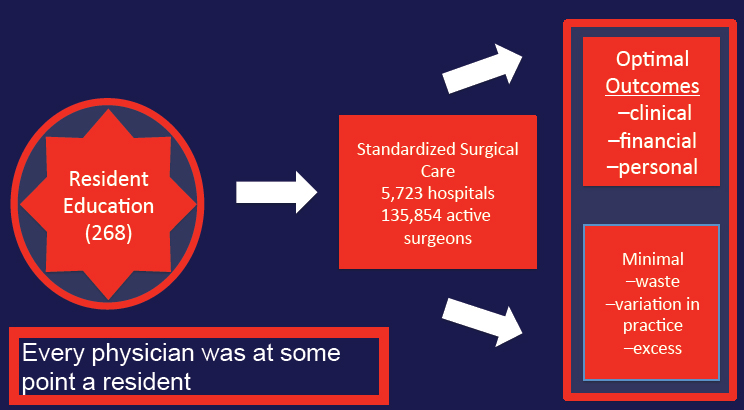

Answering GME Questions Using “Big Data” at New York University