4

Transition Planning from Old to New Ground-Control Systems

For this workshop session, the steering committee had asked the panelists to consider the following question and issues regarding Unmanned Aerial Systems (UASs) and the National Airspace System (NAS):

Transition—the path “from here to there”—is often far more difficult to define than the desired end state. This is partly due to the great challenge we often face with respect to finding the right balance between off-the-shelf technology and technology under development—the latter with greater potential but also greater uncertainty. Transition planning is also challenging because of uncertainty with respect to market evolution, and therefore the requirements for the supporting systems, and the uncertainty with respect to the operating environment. In this session, we will explore the requirements for UAS ground-control systems with an eye to articulating the essential requirements, that is, the requirements that are robust to both requirements and operational uncertainty.

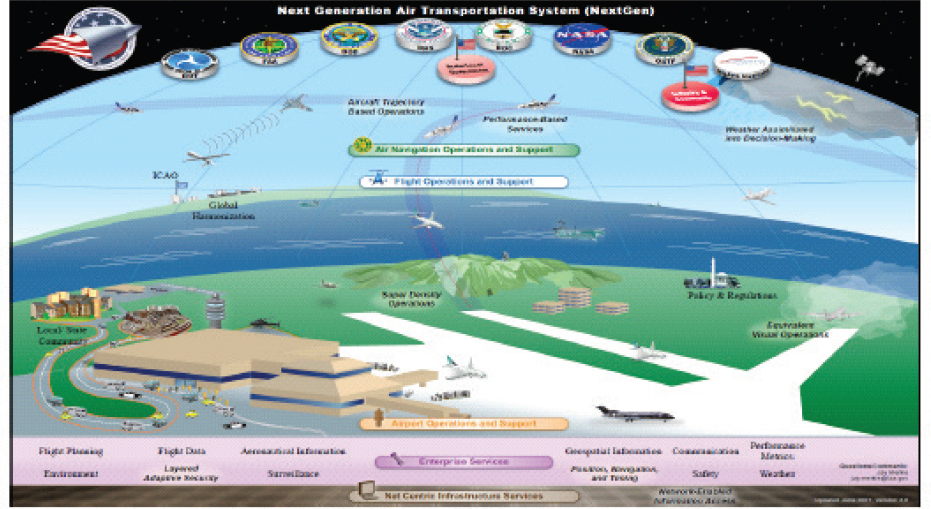

John-Paul Clarke (steering committee member) opened with the comment that “It’s the transition that always gets you in getting from here to there.” He then described the current situation, which involves airliners and a large ground-control network with one person working one airliner, which may also include a single large UAS controlled by several people, as well as a small UAS with a single ground person, and eventually perhaps a single person controlling multiple UASs. The future vision, of course, would be a much more elaborate system somewhat like that depicted in Figure 4-1: it would include many UASs (though not shown in the figure) and involve multiple agencies and numerous communication links.

However, Clarke said, the transition from current to future must be, in some respects, like rebuilding an airplane when it is in flight. “We have a great opportunity now, in truth, as we are on a verge of an industry, to think about how we build a system that can be changed in flight because we don’t know where it is going to end up.” He then emphasized the need for a modular system approach that can be changed over time as innovations become available. Also, given a future with large numbers of UASs and much information flowing throughout the system—to and from ground-control stations and UASs and involving air traffic control (ATC) as well—he stressed that communications are essential.

In concluding his presentation, Clarke turned to the issue of autonomy. “There is a lot of discussion about autonomy, way more than I ever envisioned 20 years ago, and much of the discussion is around autonomous operations.” He contrasted the term “autonomous decision making” with the term “autonomous operations”: “[Assume] I design the control system for a vehicle. You tell me the exact state the vehicle is in and the exact environment.

SOURCE: Clarke, J.P. (2018). GCS Transition Planning. Presentation for the Workshop on Human-Automation Interaction Considerations for Unmanned Aerial System Integration (slide #3). Reprinted with permission.

I can tell you what the vehicle is going to do. That is not autonomous decision making. That is autonomous operations, which is what we consider as being automation, if you want a clearer term.”

Clarke then raised and answered a question about autonomy and the design of future systems. He asked: “Can we truly develop a UAS at a commercial level with all these commercial activities that people have been talking about, with purely autonomous operation, or do we really need to have autonomous decision making, and how much should we trust the system?” He answered: “As we are thinking about designing on the side of the ATC system, we have to think about a structure that is changeable over time as we gain more and more trust in the autonomous decision making that will be essential. So that is something that, as we think about transition planning, we need to be thinking about air traffic control structures and arrangements and operating concepts that actually can morph over time as you gain more and more trust in decision making. Because, ultimately, the level of decision making that we are going to be allowed, autonomous decision making, is going to be a measure of how much we trust autonomous decision makers. So the system must be able to grow and change with that.”

Nadine Sarter (University of Michigan) emphasized that a shift from the situation of one operator to one UAS to a future of one operator to multiple UASs is not slight. Rather, such a shift leads to significant changes in cognitive demands on the operator—attention, working memory, decision making—which in turn means fundamental changes in the role and interaction of technology and operators. She separately addressed such changes and their effects on automation design approaches in terms of loss of natural multimodal cues (e.g., peripheral vision, sound), controls (e.g., their location, control-loop latency), attention (e.g., data overload and delays with multiple vehicles) and attention aids (e.g., tactile cueing), autonomy and trust (e.g., going to many means trust), and rapid switching between UASs. She repeated that, in her view, a future move to one operator for multiple UASs is not slight.

On the loss of natural multimodal cues, Sarter indicated that one can lose peripheral visual cues to an extent: that is, flow fields may be gone, and depth cues may be gone to an extent, as might the orienting function of peripheral vision. One also may lose sound, like engine noise or flow of air over the fuselage. One may lose haptic cues, such as kinesthetic cues, so “seat of the pants” flying is gone. One may lose vibrotactile cues, such as engine vibrations and turbulence.

On controls, Sarter noted that many people are concerned about how the controls have changed, or need to change, for an operator to be able to operate a particular vehicle. The number one concern is where the controls are, which may be completely different from what pilots are used to, along with mouse, keyboard, etc. She pointed out that control of latency has been discussed in many papers, especially under problematic and highly dynamic conditions, and that people are developing new forms of feedback for some of these problems, such as gravitation-force feedback, which can pull one toward a desired flight path or push one away from a potential collision. But Sarter cautioned that answers are needed about what happens when gravitational force feedback is part of a system that may make an error.

On attention, Sarter said it is a critical aspect as one moves from controlling one to many UASs: more attention guidance is needed, call it directed attention. It is not about vigilance; it is about directing attention to the vehicle requiring attention. In her view, she said, it is not the approach of merely having a light pop up and taking a look: that is not direct attention. The pop-up-light approach is a crutch, not design. Instead, one needs something that is able to provide informative feedback, which can guide and direct attention, maybe in a graded fashion, so one can balance different tasks. She offered the concept of attention guidance, perhaps through a multimodal information presentation.

On trust, Sarter agreed with what others have said, that trust is more than reliability, and she suggested digging much deeper into what trust really means and what leads to trusting the system versus not trusting the system. In terms of going from one to one to one to many, everyone seems to agree that it requires more automation. At the extreme level of automation, full autonomy, there will be a need for trust. On this point she referenced the work by John Lee, who developed the ideas of trust resolution and trust specificity.

On rapid switching between UASs, Sarter said she thinks more work is needed on how one can be given a quick snapshot to enable one’s mind to rapidly move back and forth between vehicles if necessary. In summing up this part of her presentation, Sarter reemphasized that new demands will likely call for more than “slight” modifications, and she provided a list of design process thoughts for consideration: see Box 4-1.

Sarter then elaborated on the design process by beginning with a suggestion to rethink the strategy of starting with the easy case, one to one, and then moving on to the harder case, one to many. She said she thinks that perhaps people should have started with the harder case because it is easier to go back to easier ones, rather than what is now being done. She urged treading very carefully because, in a way, everything she has heard in the workshop so far suggests that a system works because of human adaptability. The system is operating at its boundaries already with one to one, but if everyone is already pushing for one operator to many vehicles, then maybe the system is at the boundaries of a flight safety envelope. She asked: “How far can we push, and how fast?”

In closing, Sarter reemphasized heeding the lessons learned and making sure they have really been learned. She discussed the virtues of bringing together the various stakeholders and identifying what are called cognitive pressure points. She urged maintaining a systems perspective, by which she meant cognitive systems, noting that she had not spoken much about technology.