Proceedings of a Workshop

| IN BRIEF | |

|

February 2018 |

Exploring Early Childhood Care and Education Levers to Improve Population Health

Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief

Experts from the health and the early childhood care and education (ECE) fields gathered on September 14, 2017, in New York City at a workshop hosted by the Roundtable on Population Health Improvement. The workshop presentations and discussion focused on the evidence base at the intersection of the two fields; on exploring current effective collaborative strategies, ways to expand current efforts, and ways to work together in the future; and on the policy levers available to improve early childhood development, health, and learning.

After a welcome from roundtable co-chair George Isham of HealthPartners, Debbie Chang of Nemours gave an overview of the day. She began by reminding the audience of the Abecedarian preschool program in North Carolina, whose combination of early education and early health screening was studied by Nobel laureate James Heckman and found to be associated with improved health outcomes at age 35. Chang offered two reasons for looking at the intersection of health and early care and education: (1) “about 60 percent of [U.S.] children birth to age 5, not including those who are in kindergarten, spend at least part of every day in nonparental care,” and (2) families see their child care providers far more frequently than their health care provider. Thus, ECE programs, Chang added, offer the health system an opportunity to support families in other settings besides typical health care settings, and to do so on a large scale. As an example, Chang described how Nemours-operated hospitals have worked to change child care licensing policy to require healthy eating and physical activity standards.

Chang gave an overview of the day’s three main sessions on the topics of:

- Evidence—exploring why ECE and the early years are important, and what appears to work in supporting better outcomes at the interface of health and ECE;

- Cross-sector collaboration—sharing of lessons learned; and

- Policy challenges and opportunities at the intersection of ECE and health.

Following each panel presentation, there was time for questions and answers, which were followed by a “gallery walk,” an interactive session during which participants could write and review each other’s responses to three to four questions posted on the wall. Moderators presented their summary of participant comments and opened the floor to additional questions and answers. This format was followed for each of the three sessions. The workshop concluded with closing remarks and a round of personal reflections from audience members.

The organization of the workshop described above has been used to structure this Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief.

PANEL 1: THE EVIDENCE

Danielle Ewen from EducationCounsel introduced Judith Carta from the University of Kansas and Laurie Brotman from the New York University (NYU) Langone Health. Carta added that she is also the director of the Bridging the Word Gap Research Network, a program funded by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). Carta remarked on the significance of a health agency being interested in early language and the 30 million word gap by age 4 (between children growing up in poverty and those who are not). The word gap sets the stage for a gradient in vocabulary development (e.g., 500 words versus 1,100 by age 3 in low- versus high-income households), which is associated with third-grade reading, itself a predictor of high school graduation, added Carta. She noted that language learning is linked with a disparity in health, education, and life outcomes. The good news, she said, is that researchers have demonstrated that the word gap can be bridged when adults provide an environment that is rich in language; unfortunately, not all of those interacting daily with children recognize this. The research network aims to synthesize all research on prevention and intervention pertaining to the word gap, and scale it to ensure that all children receive the support they need. The network also identifies research gaps and hotspots of innovation. Carta listed a sampling of national, state, and local efforts to support brain and language development through cross-sector collaboration and communication to engage the community and/or raise awareness. These include: Too Small to Fail, New York City’s First Readers multisector collaboration, the Video Interaction Project at NYU Langone Health, The University of Chicago’s Thirty Million Words, Georgia’s Talk With Me Baby, and the Reach Out and Read program that has been implemented in all 50 states.

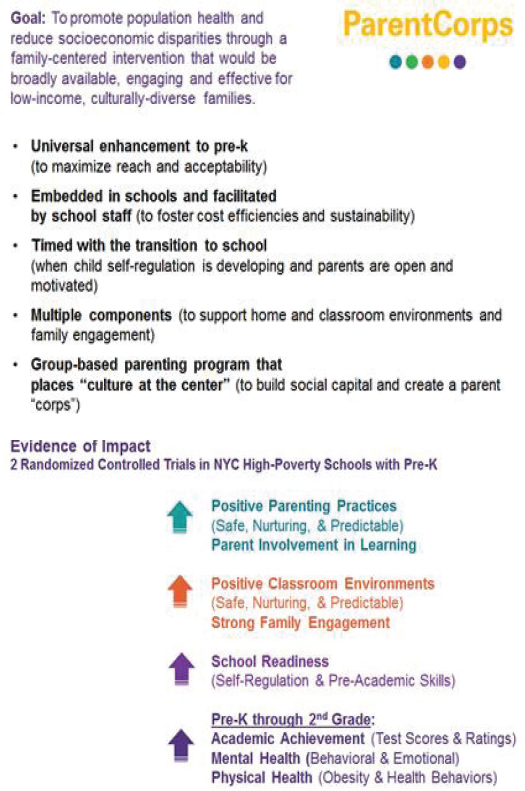

SOURCE: Brotman presentation, September 14, 2017.

Brotman described the family-centered early childhood education program at NYU Langone Health. The program, ParentCorps, is premised on evidence that poverty and adversity influence all child development and health outcomes, and a key mechanism for this influence is self-regulation. ParentCorps was created in response to a need for a universal and family-centered enhancement to prekindergarten (pre-K), and is supported by NYU Langone Health as well as city, state, federal, and foundation funding. Brotman added that the program’s simple theory of change is about bringing together professional learning, the parenting program, and the pre-K program “to create safe, nurturing, and predictable environments at school, in the classroom, and at home, and also, to create effective family engagement outreach and strong parent–teacher relationships” (see Figure 1).

Brotman shared that the program has demonstrated (and replicated through randomized controlled trials) positive outcomes in academic achievement, healthful behaviors (e.g., physical activity), and teacher ratings of child progress. ParentCorps is being implemented through a three-tiered approach in all of NYC’s 1,870 pre-K programs, serving 70,000 children per year, with a subset of programs receiving professional training, and a subset of schools receiving the full ParentCorps intervention.

Allison Gertel-Rosenberg, also of Nemours, spoke about the work of the organization and its partners at the interface of health and ECE through the national Early Care and Education Learning Collaborative (ECELC),1 which is being implemented in 10 states. The ECELC, which has received Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, state, and foundation support, has two parts: (1) informing practice through training and technical assistance, and (2) effecting systems change that includes a focus on policy and sustainability. The collaborative has enhanced integration between ECE and health in both institutional and family child care settings, as documented in a set of cases.2 Gertel-Rosenberg provided two examples of ECELC effects. In Orange County, Florida, healthy eating and physical activity were integrated in the early care and education Quality Rating Improvement System pilot. In Jefferson County, Kentucky, George Unseld Early Childhood Center reported that introducing family-style dining at snack time had several positive effects including greater independence and greater frequency of “self-care activities without adult prompts.”

Sarah LeMoine of Zero to Three described the urgency created by the speed of brain development in young children and described key challenges facing the ECE workforce and field, with a quote from the 2015 Institute of Medicine (IOM) and National Research Council (NRC) report on the birth-through-8 workforce. The report found that the workforce “had the weakest, least explicit and coherent, and least resourced infrastructure for professional learning and workforce supports” (IOM and NRC, 2015, p. 504).3 Jodi Whiteman, also from Zero to Three, described two resources developed by her organization: (1) the Knowledge and Know-How: Nurturing Child Well-Being series of eight online lessons paired with communities of practice,4 and (2) the prenatal-to-5-years-old cross-sector core competencies supported by First Five LA—eight competencies intended to enhance cross-sector collaboration. LeMoine described Zero to Three’s approach to outlining critical competencies for infant–toddler educators, building provider capacity, and supporting educator self-reflection and practice change.

Ewen facilitated discussion following the first panel, starting with a question about the language gap and hearing impairment. Carta noted that Dana Suskind at The University of Chicago (and principal investigator in the Thirty Million Words early language intervention) is a cochlear implant surgeon who began her research after realizing that children from higher-income areas caught up in language development after their implants, while their counterparts from lower-income areas lagged behind. Phillip Alberti of the Association of American Medical Colleges asked speakers how they address the issue of health inequity and education inequity and if specific measures are used, and also asked if the programs described use an implementation science approach to ensure that all communities, regardless of size and other characteristics, can derive equal benefits from the programs. LeMoine responded that Zero to Three uses the Harris Foundation’s Diversity-Informed Infant Mental Health Tenets along with metrics that include a diversity, fairness, and equity lens. She added that implementation includes training the trainers to build capacity as needed in each setting.

Brotman noted that her team’s research includes looking at outcomes by gender and race and ethnicity. Terry Allan of the Cuyahoga County Board of Health asked about durability of effects in ParentCorps. Brotman replied that the findings have been replicated, studies included follow-up through early adolescence or through second grade, and some follow-up is ongoing.

FIRST GALLERY WALK (INTERACTIVE SESSION) AND REPORT BACK

Following the first panel, participants had the opportunity to share their responses and comments in a gallery walk activity. The three questions were:

- How can the field better apply what is known at the interface of ECE and health (e.g., screening for developmental milestones)?

- What are the gaps and white spaces that need to be prioritized?

- What are new insights (e.g., what you need to know about parents, teachers, and caregivers)?

Valora Washington from the Council for Professional Recognition provided a high-level summary of gallery walk input, organized by four principles: (1) respect for parents and families, (2) competence in terms of infrastructure and a vocabulary for collaboration, (3) strengths to build on and leverage, and (4) equity. In the subsequent open discussion, Alan Mendelsohn from the NYU School of Medicine remarked that health care can play a key role in preventing disparities in early childhood development and school readiness, describing the strengths of the pediatric platform in engaging

__________________

1 See https://healthykidshealthyfuture.org (accessed November 7, 2017).

2 The cases may be found at https://healthykidshealthyfuture.org/links/case-studies-childhood-obesity (accessed November 7, 2017).

3 IOM and NRC. 2015. Transforming the workforce for children birth through age 8: A unifying foundation. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

4 See https://www.zerotothree.org/resources/1217-knowledge-and-know-how-lesson-demo (accessed November 7, 2017).

with families in the early months of life when pediatric visits are frequent. Mendelsohn added that evidence-based programs such as Reach Out and Read need to be scaled up.5 Whiteman replied that the Zero to Three Healthy Steps model integrates behavioral health specialists in pediatric settings. Whiteman added that reimbursement by both public (i.e., Medicaid) and private insurance is an evolving challenge, requiring advocacy both at the federal and state level.

Isham asked about the incentives for pediatric groups of outcomes that could be incorporated into value-based payment models, a question that resonated with other commenters, one of whom noted that her organization advocates for changes to reimbursement. A participant stated that New York State is in transition from fee-for-service reimbursement to value-based payment models, and this work will include attention to developing metrics that can be shared between ECE and pediatricians.

PANEL 2: CROSS-SECTOR COLLABORATION

The second panel, focusing on the mechanics of cross-sector collaboration, was moderated by Chang, who first introduced George Askew from the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, Division of Family and Child Health. Askew briefly summarized New York City’s key statistical figures for early childhood, and described his bureau’s nascent Early Childhood Health and Development Unit. The bureau also collaborates with the Division of Mental Hygiene and other agencies and activities (including THRIVE, the NYC first lady’s mental health initiative) to ensure provision of mental health consultation services to support social-emotional learning (SEL) activities in ECE settings across NYC.6 Askew added that policy change was needed to support such cross-sector and integrated work in NYC, including changing the health code to permit early intervention therapists to enter ECE settings to provide services. At the state level, Askew added, New York State has launched the First 1,000 Days on Medicaid initiative to leverage Medicaid resources to support some services needed in early childhood.

Kimberly Shinn-Brown from the Ozarks Area Community Action Corporation (OACAC) Head Start provided a brief introduction to the Springfield, Missouri, Head Start program and the comprehensive array of federal requirements that structure services at this and all Head Start centers. Shinn-Brown said that it is fundamental to recognize that children whose health and well-being are suboptimal, from experiencing trauma to untreated dental caries, are unable to thrive in some ECE settings. Head Start programs, Shinn-Brown’s included, leverage Medicaid and private insurance funds to offset the cost of providing an array of services. The program also provides health literacy training (inspired by the work of Ariella Herman7) and the services of a family advocate who supports families in choosing and pursuing goals important to them.

Advocates also help families maintain health insurance coverage because Missouri has a 6-month waiting period when people do not re-enroll in Medicaid. Missouri rural areas experience significant challenges with access, especially for behavioral health services. Some Head Start programs, like OACAC’s, have a health services advisory committee that is interdisciplinary, includes parents, and provides guidance with decision making about a center’s policies and procedures, as well as services, referrals, and supports. Effectiveness of coordination with other early childhood programs (e.g., WIC [the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children]) and federally mandated services (e.g., those described in the IDEA [Individuals with Disabilities Education Act]) may vary, Shinn-Brown noted.

Krista Scott of Child Care Aware began by orienting the audience to the federal Child Care Development Block Grant that authorizes the Child Care Development Fund, administered by states, territories, and tribes, and that provides subsidies accompanied by quality and other regulations. Scott then gave a brief overview of the work of her national membership organization for resource and referral agencies that provides consumer education and conducts training and professional development for ECE providers. Scott described two reports that have led to establishing benchmarks for child care health and safety, and other activities to integrate health into ECE quality standards and measures (see Box 1 for a brief overview provided by Scott on the state of child care health standards). In the area of equity, the work of Child Care Aware around the country involves supporting 68 cross-sector partnerships that help to address locally identified needs, such as food access and safe spaces to play. Scott added that to support healthy communities, quality child care should be accessible and affordable and be integrated with efforts to address the social determinants of health, from physical environments to financial status.

Michelle Suarez from Prosper Lincoln described her organization’s work of mapping, measurement, and cross-sector partnerships, supported in part by the Community Health Endowment created when a public hospital was privatized. The organization mapped well-being and health outcomes across the community and identified life span

__________________

5 See http://www.reachoutandread.org (accessed November 7, 2017).

6 SEL is defined by the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning at http://www.casel.org/what-is-sel (accessed November 7, 2017).

7 See, for example, https://nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Building-Health-Literacy-and-Family-Engagement-in-Head-StartCommunities.pdf (accessed February 9, 2017).

differences based on geography. Lincoln stakeholders’ community-based process prioritized three areas of focus for Prosper Lincoln: (1) early childhood as a key pathway to an equitable future, (2) nurturing employment skills, and (3) creating opportunities for innovation. The community mapping work included outlining an Early Childhood System of Care, which led to forming three workgroups (ECE quality, comprehensive health, and communication and messaging). The communication and messaging work has included attention to linguistic and cultural accessibility and competence, as well as engaging parents around the topics of brain development and executive function.

Discussion at the end of the session began with a question about what brings people from the different sectors to the table. Answers included when elected officials prioritize early childhood outcomes, when there is community interest, and when funding and technical assistance are available. Other remarks by individual workshop participants highlighted the need for cross-sector focus on children with disabilities; the importance of enforcing ECE-related changes in health code (e.g., to integrate oral health requirements or healthy eating and active living supports); and the importance of public health interactions with not only the education sector, but also housing, parks, and others.

SECOND GALLERY WALK (INTERACTIVE SESSION) AND REPORT BACK

The second set of questions presented to participants as part of a gallery walk were:

- How can we accelerate cross-sectoral collaboration in ECE and health? What do you need to help you and your organization collaborate effectively?

- What are the main barriers to collaboration and the solutions to them?

- What have we learned from other cross-sector collaborations that could help to inform ECE/health interactions?

- What new insights can be shared?

Larry Pasti of the Forum for Youth Investment summarized some of the overarching themes he identified while reviewing gallery walk responses. Workshop participants listed such issues as the need for collaboration along the cradle-to-career pipeline; the importance of connecting the dots and efforts (and sustaining linkages) on brain development, social and emotional learning, and self-regulation; trust versus turf issues at the interface between sectors and organizations; attention to the history of collaboration in the community; the importance of engaging families in devising and implementing solutions; and finally, the fact that sustainability is not just about money, but that it also applies to the workforce and collaboration.

Elizabeth Groginsky from the District of Columbia Office of the State Superintendent of Education told participants about the District’s initiative Our Children, Our Community, Our Change,8 and the local implementation of the Early Development Instrument,9 which will be used by the city periodically to map child well-being from pre-K through grade 4. The District of Columbia, added Groginsky, has integrated the data into its child care and development fund plan and its collaboration with other local government agencies.

PANEL 3: POLICY CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES AT THE INTERSECTION OF ECE AND HEALTH

The day’s third and final panel on the policy context that shapes workforce, financing, and other aspects of ECE was moderated by Jacqueline Jones from the Foundation for Child Development. Jones noted that the child care workforce represents multiple workforces given the wide range of training and settings, but there is wide agreement across stakeholders that ECE workforces need to be supported in many ways, including training, competency development, and compensation, to “move children farther along.” Jones added that the field has only two certifications: the Child Development Associate (CDA) credential for entry-level teachers and the National Board for Professional Teaching Standards for accomplished teachers, with nothing else in between—there is no national certification to define expectations beyond entry level. Jones introduced speaker Marcy Whitebook of the University of California, Berkeley, and speakers Rolf Grafwallner from the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO), Aly Richards of the Permanent Fund for Vermont’s Children, and Gloria Higgins of Executives Partnering to Invest in Children.

Whitebook began her remarks by showing that unlike in the case of K–12 education, the United States does not regard ECE as a public good, but rather as a family responsibility. As a result, she noted, the federal government intervenes in the ECE market on behalf of low-income families, but the limited (as a proportion of the nation’s gross domestic product) resources allocated do not meet the need. Similarly, state-funded preschool services do not cover most 3- to 4-year-olds, and Head Start does not even cover half of the number of children who qualify. Whitebook referred to the 2015 IOM and NRC report Transforming the Workforce for Children Birth Through Age 8: A Unifying Foundation that underscored the complexity of ECE (which is comparable to K–12 teaching) and also highlighted that the well-being of adults interacting with children is a key dimension of successful child development. To the lack of recognition of and appropriate compensation for ECE workers, Whitebook listed additional challenges to progress at the interface of ECE and health (see Box 2).

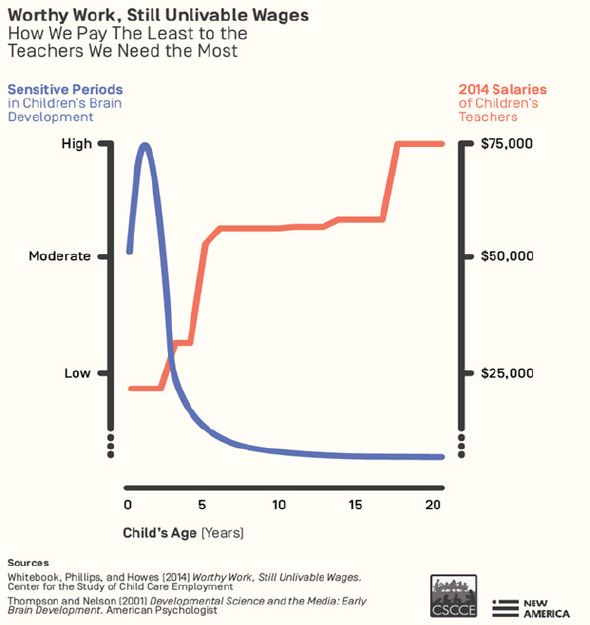

Whitebook shared research indicating that economic insecurity of ECE workers (see Figure 2) and a common lack of employee benefits are causes of significant stress further exacerbated by work demands. Effective ECE teachers are dynamic and have high executive function—capabilities that research (e.g., IOM and NRC, 2015) indicates are vulnerable to the stress and poor health status that affect this workforce. In her closing, Whitebook remarked that adults “who care for and educate young children have a great responsibility. We, in turn, I think have a great responsibility to these early childhood teachers, of whom we have been expecting so much, but to whom we still provide so little.”

Grafwallner described his role at CCSSO as that of an advisor to the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning. He began by explaining that the latest iteration of the elementary and secondary education legislation, which was called the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), called for integration of social and emotional learning into school curricula and accountability plans. The five competencies of SEL are self-awareness, self-management, responsible decision making, relationship building, and social awareness. Although these are identified in reference

__________________

8 See http://www.raisedc.org/ourchildren (accessed November 7, 2017).

9 See http://www.raisedc.org/ourchildren/edicommunitytool (accessed November 7, 2017).

to K–12 education, ECE research on these skills is rich and shows the links between ECE and later education, particularly in terms of early childhood mental health consultation and multi-tiered support systems in K–12. Grafwallner highlighted one example from the state of Iowa, which is establishing data systems to follow SEL indicators from kindergarten through grade 12 through their Safe and Supportive Schools Condition for Learning Index. Gloria Higgins talked about the role of business advocacy in supporting ECE, with Colorado as an example. Employers, she asserted, recognize that it is crucial to consider the full breadth of workforce needs, particularly if they seek to attract younger workers who have or are planning to have children. Colorado offers tax-advantaged opportunities for businesses, which in turn provide an opportunity for employers to provide child care options for their employees. Higgins spoke of two options to provide a child care benefit: either (1) offer it as a part of a cafeteria plan for using pretax dollars for specific expenses, or (2) offer it as a tax-free dependent care assistance contribution of up to $5,000, a cap put in place in 1982 and which Higgins suggests ought to be updated for inflation. Colorado has a child care contribution tax credit that is 50 percent of the amount a company contributes to a child care provider that serves a high proportion of that company’s employees.

SOURCES: Whitebook presentation, September 14, 2017; Whitebook, M., D. Phillips, C. Howes. 2014. Worthy Work, Still Unlivable Wages. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, http://cscce.berkeley.edu/files/2014/ReportFINAL.pdf (accessed December 18, 2017); Thompson, R. A. and C. A. Nelson. 2001. Developmental Science and the Media: Early Brain Development. American Psychologist 56(1):5–15.

Aly Richards talked about Vermont’s concerted effort to ensure that all of the 6,000 children born in the state each year thrive. Health care, business, public, and philanthropy sectors are working in concert since the Permanent Fund’s founding in 2000 to support ECE efforts, with the goal of ensuring “high-quality, affordable early care and learning for all who need it in Vermont.” Richards stated that the fund sees home visiting, early care and learning, and pediatrics as three legs of a stool, and given the return on investment, it makes complete sense to support a system of quality, affordable, and accessible ECE. Richards explained that 70 percent of Vermont children under 6 have working parents, but 47 percent of those children lack access to regulated child care and 79 percent lack access to high-quality child care. Given this reality, the fund views ECE as “an innovative platform for community health,” and its partners in the state are working to integrate child and family health services with ECE in community settings. Richards shared specific examples of the alignment of health and ECE, such as the Vermont health care system, itself highly integrated, having trained all child care providers on developmental screening and referrals.

In her summary remarks, Ewen shared some principles that she identified in the days’ discussions. First, the circle of partners needs to be drawn very wide, because “everybody is doing early childhood,” not just ECE providers, but also health care providers, social service providers, workforce educators, those who work to prevent bullying and gun violence, and others. Second, there are roles for all partners to play. Third, “as we talk about equity,” she added, “we need

to remember that all voices are important.” The fourth and last principle Ewen described is “asking hard questions about what outcomes matter.” The achievement gap, she explained,

. . . comes from a lack of [playground] slides. It comes from children who don’t have access to parks. It comes from children who don’t get exposed to science. So, let’s think about what outcomes matter in a very different way when we are creating that intersection of [ECE] and health.

Ewen also acknowledged that progress at the interface of health and ECE involves both being intentional (i.e., creating new programs, practices, and policies), and opportunistic, by “jumping on the train that is leaving the station.”

THIRD GALLERY WALK (INTERACTIVE SESSION) AND REPORT BACK

Participants in the third gallery walk of the day were asked to answer the following questions:

- What are the priority interventions and policies related to early childhood care and education that should be spread and scaled?

- What policy actions can be taken to address some of the challenges in spreading and scaling effective early childhood care and education interventions and programs?

- What needs to be done to support and increase investments for new ideas and innovation in early childhood care and education?

- What policy actions can be taken to increase collaboration and synergies between those working in the health sector and the early childhood care and education sector?

To start her reporting about the gallery walk responses, Paula Lantz of the University of Michigan remarked that the lack of public support for ECE “reinforces and exacerbates inequalities for kids and [. . .] it creates a lot of stress for most families and caregivers.” The stressors are both psychosocial and financial and play out across the whole life course.

“How do we motivate greater investment in children?” Lantz asked. Demographics could be a powerful argument, she asserted, given the national trajectory toward a higher dependency ratio (working population versus dependent population of children and older people). In other words, she added, the lack of public investment in supporting ECE (along with family leave, etc.) may serve as a disincentive to have children.

CLOSING REFLECTIONS

Phyllis Meadows of The Kresge Foundation offered closing remarks, highlighting the themes of shared outcomes, a need for sustainable funding, the importance of collaboration and leadership to support it, and the need for community-driven solutions to the challenges of early childhood. Meadows concluded with a provocative framing:

What if we had a society where all children, whether they are suburban, rural, frontier, regardless of race, and social economic status, have available, affordable, relevant access to the services they need to be healthy, to thrive, to learn in prosperous society. What would that look like?

Isham opened the floor to final remarks from the audience. Alberti commented on what he viewed as a gap in the day’s discussions, namely, the need for engagement of a wide range of community partners in advocating for prioritizing early childhood. If the moral argument is insufficient, what argument will be effective, he asked, noting that racism, classism, and xenophobia are among the factors that shape people’s attitudes toward early childhood. Higgins commented that it could be helpful to persuade health care partners to endorse (e.g., through advocacy) the importance of ECE to improving population health outcomes.

Mary Pittman of the Public Health Institute commented that since the ECE sector is largely a private market, “what if you could braid funds from WIC, from Medicaid, from food stamps, from all of the tax incentives, and have a pool of funds that is set aside to make sure that all of the lowest income families have free access to the best supports in early childhood?” Chang remarked that sustainability has to do with finances as well as with embedding innovative interventions and services into existing programs. Isham thanked the participants and adjourned the workshop.♦♦♦

DISCLAIMER: This Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief was prepared by Alina B. Baciu as a factual summary of what occurred at the workshop. The statements made are those of the rapporteur or individual workshop participants and do not necessarily represent the views of all workshop participants; the planning committee; or the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

PLANNING COMMITTEE FOR EXPLORING EARLY EDUCATION LEVERS TO IMPROVE POPULATION HEALTH: A WORKSHOP*

Debbie Chang, Nemours; Marquita Davis, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; Jennifer Frey, The George Washington University; Jacqueline Jones, Foundation for Child Development; Paula Lantz, University of Michigan; Phyllis Meadows, The Kresge Foundation; Larry Pasti, Forum for Youth Investment; and Valora Washington, Council for Professional Recognition.

*The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s planning committees are solely responsible for organizing the workshop, identifying topics, and choosing speakers. The responsibility for the published Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief rests with the rapporteur and the institution.

REVIEWERS: To ensure that it meets institutional standards for quality and objectivity, this Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief was reviewed by Marquita Davis, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; Nancy Lim, National League of Cities; and Bridget Walsh, Schuyler Center for Analysis and Advocacy. Lauren Shern, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, served as the review coordinator.

SPONSOR: This workshop was partially supported by Aetna Foundation, The California Endowment, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Fannie Rippel Foundation, Health Resources and Service Administration, Kaiser Permanente East Bay Community Foundation, Kresge Foundation, Nemours, NY State Health Foundation, NYU Langone Medical Center, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Samueli Institute, and Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center.

For additional information regarding the workshop, visit http://nationalacademies.org/hmd/activities/publichealth/populationhealthimprovementrt/2017-sep-13.aspx.

Suggested citation: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2018. Exploring early childhood care and education levers to improve population health: Proceedings of a workshop—in brief. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: https://doi.org/10.17226/25030.

Health and Medicine Division

Copyright 2018 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.