– 2 –

“Traditional” and “New” Crime: Structuring a Modern Crime Statistics Enterprise

IN THIS CHAPTER, WE RESUME where we left off at the end of Report 1 (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016), with a detailed recommended classification of crime (offenses) for statistical purposes (Appendix D of that volume). After considering the extent to which the proposed classification is in concordance with current nationally compiled crime statistics, we outline some of the fundamental challenges to assembling indicators of crime for the United States as a whole but in a way that meets user and stakeholder needs for disaggregation and comparison. We then build from the recommendations in Report 1 to suggest general contours of an improved national crime statistics program.

2.1 MATCHING NEW CLASSIFICATION TO CURRENT PRACTICE

The table and commentary in Appendix C illustrates our basic assessment of the match between categories in our proposed crime classification with the Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Program’s Summary Reporting System (SRS) and, particularly, the National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS) that is now poised to replace the SRS as the primary source of information on crimes reported or otherwise known to the police. Through

this matching, we offer a rough assessment of how consistent our proposed definitions or concepts for a particular offense are with the UCR’s concepts (roughly, whether they are generally closely consistent, partially consistent, or inconsistent/uncovered in the current data), and so whether the data (again, principally NIBRS) are capable of generating estimated counts or measures of specific offenses that may be disaggregated by geographic or demographic characteristics.

For completeness’s sake, the “full match” in Appendix C also includes a column indicating the extent of consistency and coverage of the offense in the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS). We return to this point in other parts of this chapter and this report, but the basic features of the match to the NCVS warrants a comment up front. An unavoidable impression that one might draw from the table in the appendix is that the NCVS and our classification make for an exceptionally poor fit—but that is a very misleading impression. Most crime is a relatively rare event in the statistical sense, so the vast majority of the respondents to a household survey like the NCVS will not have victimization experiences to report for any particular offense. The sample size of the survey would have to be impractically large to achieve fine-grained detailed estimates, and so tabulations from the NCVS—by necessity—tend to stick to offenses that occur most frequently and to groupings of offenses (e.g., violent crime relative to property crime). The comment that is in order upfront is simply that the seeming mismatch between our classification and the NCVS should not be interpreted as criticism of the value of the NCVS. Indeed, as we will discuss later in this chapter, survey-based measures of crime are an integral part of the system of data collection systems we envision.

The information from the full match in Appendix C is conveyed in a more condensed, approachable form in Table 2.1; it focuses on the rough correspondence between our classification’s major subcategories and concepts in UCR/NIBRS.

The most striking result of the match can be gleaned by glancing down the columns of Table 2.1: The coverage of our classification’s categories in NIBRS is, overall, very sparse. This is not surprising, given that the express intent in Report 1 was to cast a very wide net in defining “crime” offenses through our classification, the intent of a statistical classification to be a partitioning of the entire range of the phenomenon in question. As in Report 1, we do not intend for this result to raise concerns that assembling modern crime statistics is a futile task—it is not—but rather to be candid about gaps in knowledge and to be aspirational in seeking a fuller picture of crime.

However, the match is also markedly differential in nature. It is worth reminding, at this point, that there is no gradation of importance or seriousness (or anything else) implied by the numbering of categories in our classification. Nonetheless, the numbering scheme is such that top-level categories 1–5 correspond to what might be considered “traditional” crime: the well-known,

| Category in Panel’s Classification | Coverage in UCR/NIBRS | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Covered | Partially Covered, or Different Concept | Not Covered | |

|

Murder and intentional homicide Nonintentional homicide |

— |

Assisting or instigating suicide Unlawful euthanasia Unlawful feticide Unlawful killing associated with armed conflict |

|

Coercion |

Assault Threat Acts against liberty Trafficking in persons Dangerous acts |

Slavery and exploitation Negligent acts Acts intended to induce fear or emotional distress Defamation Discrimination Acts that trespass against the person |

|

Rape |

Sexual assault Sexual exploitation of adults |

Sexual violations of a nonphysical nature Sexual exploitation of children |

|

Robbery | — |

Terroristic or disruptive threats to buildings or critical infrastructure |

|

Burglary Theft |

Property damage Acts against computer systems (unlawful access to a computer system) |

Acts against computer systems (all other) Intellectual property offenses |

|

— | Unlawful acts involving drug equipment or paraphernalia |

Unlawful possession or use of controlled drugs for personal consumption Unlawful cultivation or production of controlled drugs Unlawful trafficking or distribution of controlled drugs |

|

Forgery or counterfeiting |

Fraud (identity theft; false pretenses; mode-specific types such as wire fraud) Corruption Acts involving proceeds of crime |

Fraud (generally, including fraud against businesses or establishments or government agencies) |

|

— | Acts against public order sexual standards |

Acts against public order behavioral standards Acts related to freedom/control of expression Acts contrary to public revenue or regulatory provisions Acts related to migration Acts against the justice system Acts related to democratic election Acts contrary to labor law Acts contrary to juvenile justice regulations or involving juveniles/minors |

|

— | — | Acts involving weapons, explosives, and other destructive materials Acts against national security Acts related to organized criminal groups Terrorism |

|

— | Acts against animals |

Acts that cause environmental pollution or degradation Acts involving the movement or dumping of waste Trade or possession of protected or prohibited species of fauna and flora Acts that result in the depletion or degradation of natural resources |

|

— | — | Violations of military law Violations of tribal law Torture Piracy Genocide War crimes |

NOTES: —, not applicable. Full version of match is presented in Appendix C.

violent interpersonal “street” crime and property offenses that dominate the nation’s current crime statistics. Within these broad sectors, agreement between our classification’s traditional crimes and NIBRS is reasonably good. That said, the middle “partial match” column for the traditional crimes significantly downplays the magnitude of differences in concept between our definitions and NIBRS’s definitions—perhaps most importantly the radically different conceptualization of assault and threat that we postulated in our classification (dissolving the UCR concept of aggravated assault). By comparison, our categories 6–11 correspond roughly to “new” types of crime—new, in most cases, in the sense of being new in statistical tallies, having received little to no standardized national collection to date even though they have been serious problems for decades. In this range, there are very few entries in the pure “covered” column but a few hopeful signs in the “partially covered” column of Table 2.1. Category 6, acts involving controlled substances, is interesting middle ground—certainly, a group of offenses that the public might think are well documented by the nation’s crime statistics. But, in current practice, the UCR’s categorization of “drug/narcotic offenses” is sufficiently vague and the UCR measure (arrests only) is sufficiently detached from the full behavior of interest that we deem the match between NIBRS and our classification to be poor. Hence, it makes sense to include controlled substance offenses as “new” crime.

2.2 CONTOURS OF A MODERN NATIONAL CRIME STATISTICS INFRASTRUCTURE

Against this backdrop—lessons learned from decades of data collection under current structures and a conceptual framework for understanding what a complete picture of crime should look like—we now articulate our vision for a modern national crime statistics infrastructure. In doing so, we also render three formal conclusions, main messages that we hope to convey through this report. These three conclusions, and the balance of this chapter, can most succinctly be described as arguing that modernizing U.S. “crime statistics” demands attention to both parts of that phrase. Our Report 1 and recommended classification collectively argue that improved crime statistics require a broader concept of crime, and we return to this point with our third conclusion. But we begin with arguments that emphasize that there is a need for more statistics in modern crime statistics, too.

2.2.1 Measuring Crime, Not “Enumerating” It

Appendix B provides fuller historical background behind the following statements, but two damaging trends took hold during the decades in which the

UCR Summary system was effectively the sole source of nationally compiled crime statistics:

- Undue sense of completeness and accuracy: Having achieved high (and genuinely impressive) levels of voluntary contribution of data by local law enforcement agencies, the tenor of communications about the crime data changed. Near complete participation was tacitly characterized as universal participation—with hints about lapses in reporting by individual agencies (in whole or for some months in the year) being expressed not at all or at best in footnotes or auxiliary documents. Frank acknowledgments of limitations in the data gave way to broad, declarative summary statements and authoritative-appearing tables. Fundamentally, notions of uncertainty and error—for instance, the extent of imputation required due to agency nonresponse or the extent of measurement and conceptual error—dropped out of view. At the same time, the report Crime in the United States was largely taken to define “crime in the United States”—presented and commonly interpreted as an exhaustive enumeration of crime in the nation when in fact it never was and (limited to selected offense types and to offenses reported to law enforcement) it never could be.

- Reduction to coarse, short-term changes in a few broad categories of crime rates: When counts of offenses are all that are available, absent detail and context, attention naturally focuses where it can—on the year-to-year upticks or downticks of national level counts. While information on year-to-year changes has utility, it is not sufficient to more fully inform understanding of any changes in the nature of crime. It also diminishes the key potential value of nationally compiled crime statistics to the wide array of data users and stakeholders, for whom the overriding potential utility of the UCR data is comparison of a jurisdiction’s crime conditions with those in other jurisdictions. The counts (absent context and understanding of possible errors within them) render such comparisons inapt and potentially misleading.

As also recounted in Appendix B, more recent years have seen new concepts or offense types emerging in national interest—arson, hate crime, human trafficking, cargo theft—forced into the count-intensive, bookkeeping-type UCR Summary mold by default.

Accordingly, a first principle for modern crime statistics is that coarse tallies are not enough to meet the needs of the full range of users and stakeholders. For any given offense type, the starting point of the discussion should always be the basic question: What does the nation need to know about crime, and how may it best be measured? A major part of the answer has to be acceptance that measurement of crime will necessarily involve uncertainty, which should be documented and scrutinized. This report is an argument for recasting the

crime statistics problem—for “traditional” and “new” crimes alike—as one of measuring and estimating levels of and trends in crime and not simply (or only) counting it.

Conclusion 2.1: The aim of modern crime statistics is the effective measurement and estimation of crime. Accurate counting of offenses and incidents is important, but the nation’s crime statistics will remain inadequate unless they expand to include more than just simple tallies with no associated measure of uncertainty or capacity for disaggregation. Through the collection of associated attribute data, the crime statistics we suggest should—at minimum—enable the analysis of data in proper geographic, demographic, sociological, and economic context, and provide the raw material for important measures related to an offense (such as the harm it causes) in addition to its count.

There are numerous major issues packed into this call for a return to estimation in crime statistics; we discuss a few in the balance of this section, and more detailed treatments of others are developed in Appendix D.

Nondenumerable Crime

The last sentence of Conclusion 2.1 has application for some traditional crime offense types. As described in Appendix B, one of the earliest appeals for information beyond a total, aggregate incident count was for the monetary value of estimated property loss, particularly for the pure property crime of larceny-theft. That shortcoming led to the development of UCR Summary’s Supplement to Return A. The exact manner by which that information is currently collected was heavily criticized in our panel’s workshop-style sessions with crime data stakeholders. They found dubious the totaling of property values by offense type and crude (and somewhat dated) property type categories. By comparison, collection of detailed incident-level property loss data would be more useful—and arguably essential for understanding the dynamics of larceny—because of their capacity for aggregation and recombination.

Yet it is the “new” types of crime in categories 6–11 of our classification, especially, that lead us to state that last clause of Conclusion 2.1 as we do. This is because many of the new offenses defy the application of consistent counting rules—and, moreover, are effectively nondenumerable because raw counts may actually be misleading or meaningless absent availability of other information. Some examples may be useful to consider:

- Deployment of ransomware, malicious software that denies users access to their own data and computer systems until a ransom is paid electronically: Counts of ransomware deployments do relatively little to improve

-

understanding of the severity of the problem. The deployment of a single ransomware script may be aimed at a small set of users or be propagated worldwide, touching vastly different numbers of downstream victims. Likewise, there are certainly material differences in the amount of damage caused by a single ransomware deployment that locks up an individual user’s machine and one that hobbles use of the automated information systems of an entire hospital or medical group.

- Environmental violations: Technically, the same offense count (1) would apply to the improper disposal of a laptop computer battery as to a deliberate spill of large amounts of toxic materials into the water or air. For such offenses, noncount measures of interest may be crucial to consider, such as the amount of pollutant discharged into the environment, the percentage by which emissions exceed values permitted by regulation, or the size of the population that may be affected by the discharge. Even when the size of two offenses are similar, the consequences may not be. Spilling the same number of barrels of oil into a water supply may not be equivalent to spilling the same number of barrels of oil in a nature reserve or an industrial site.

Ultimately, the core component of crime statistics is the assessment of the level and characteristics of crime and trends in its occurrence, and so it stands to reason that some manner of count is essential. Again, Conclusion 2.1 underscores that which has already been said about crime statistics focused overly (or exclusively) on aggregate tallies, as in the UCR System—those coarse counts, incapable of disaggregation by factors of interest or isolated from other pertinent information that are more descriptive of a particular offense better than an incident tally, are simply insufficient in a modern information environment. Counts capable of disaggregation and detailed contextual analysis may be ideal for traditional offense types, but the new crimes in particular require supplemental information because counts alone are acutely insufficient for understanding and use.

Challenge of Timely Crime Data

Another aspect of measurement that presents challenges for national-level statistics of all kinds is timeliness. This can be difficult for the broad range of offense types in our classification, but especially for the crimes in categories 6–11. The important questions to consider for each offense in the classification is what does the nation need to know, and how best might it be measured, which invites the follow-up question of how the best measure is determined. The common adage that things can be done cheaper, faster, or better—but not all three simultaneously—rings true and is a constant tension. As we will argue in more detail later, our global preference is for better in the sense of accuracy and

data quality, but timeliness can become a paramount issue for certain types of crime, such as homicide and violence. Timeliness regarding national-level crime statistics refers not only to the availability of crime data for analysis and policy decision-making, but also to conceptual decisions about when some crimes can be determined to have occurred.

The panel’s Report 1 discussed some of the problems that are associated with the fact that national crime statistics typically are released by the FBI in its annual publication Crime in the United States approximately 10 months after the collection year ends. (For example, crime statistics for 2016 were released in October 2017.) Report 1 notes that in 2006, and again in 2015, national and local concerns about apparent homicide and crime increases were growing. Although police departments had information about their own local crime problems, the lack of timely UCR data for comparison purposes made it difficult for law enforcement to determine whether increases were unique to their own cities or part of a broader national pattern. In an effort to obtain data to evaluate these problems, police organizations could not turn to recent UCR data, so they surveyed their membership about local crime problems. News media, advocacy groups, and other organizations also began creating their own databases derived from available local police departments’ website information. This nonsystematic data-gathering can be very problematic and can result in unproductive debates about the causes of the apparent increases and resource needs. Homicide increases are of great concern, and for this type of offense, more timely data release is critical.

Yet, for other types of offenses, the issue of timeliness involves different conceptual dimensions. For example, in conspiracy crimes, it may take time for the crime to manifest and be detected by law enforcement. In consumer fraud or credit card fraud, it may take time for even the victim of an offense to know that it has occurred. In these types of instances, there can be considerable time between the occurrence of an incident and the point at which it can be detected by survey or other methodologies. However, for these offense types, the issue of quick and timely data availability for comparison purposes is arguably less important than it is for crimes involving homicide and serious violence. The speed at which data can be made available is expected to vary across offense types, but when there is evidence that data are urgently needed for important decision-making, as in the case of homicide and serious violence, that information should be released more quickly.

Today, there is an ever-increasing desire for data that are available quickly, and technology itself has enabled construction of data resources with speed unthinkable in past years. Web-scraping methods that scour Internet pages, media accounts, or social media postings in search of information about a topic of interest have found some application in the analysis of crime. Media organizations and individual academic researchers are now maintaining their own repositories of data on homicides, shootings, or terrorism-related

incidents. Another prominent, and relatively long-standing, example growing out of academic research is the Global Terrorism Database that mines media stories on terrorism-related events as its first-step input, and which has been characterized by the investigators as tapping into a “fire hose” of news media articles (Miller, 2014:6). The development of terrorism event databases and challenges encountered in the experience of the Global Terrorism Database are described by LaFree et al. (2015) and LaFree (forthcoming), but one lesson is that thoughtful conceptualization of the problem at hand and an infrastructure of data quality controls (e.g., verification) are critical to the reliability of these data. In other words, it is good to have an aspirational vision of data resources—on crime, or anything else—that are truly “real-time” in nature—but even real-time may involve reconciling occurrence time lags between when an offense occurred and when it became detectable. Moreover, they should involve some lag in order to satisfy basic data quality requirements.

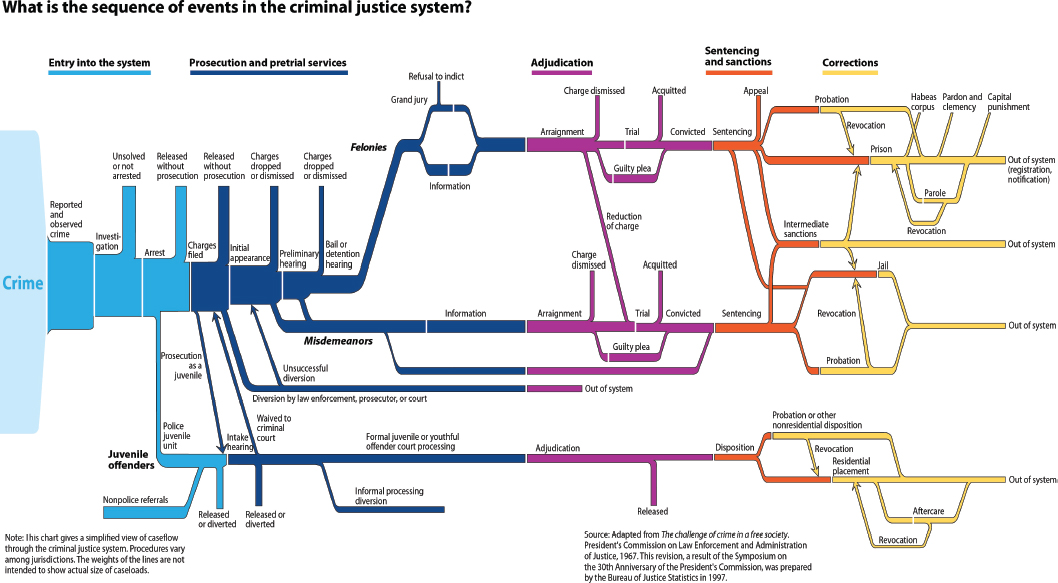

It is instructive, at this point, to recall the familiar funnel model of operations in the criminal justice system (see Figure 2.1). The occurrence of crime is the wide, open end at left of the funnel and the later phases (investigation through adjudication and on through corrections) are the increasingly thinner segments progressing to the right. Given multiple possible measures of the same offense, the understandable general preference is for the one closest in time to the actual occurrence, and so the one that falls leftmost in the crime system funnel—the earliest point at which an occurrence is reported by a victim or observed by actors in the justice system. But this is not always possible, and may necessitate glimpses further to the right in the justice system funnel than may be desired, simply to make measurement possible. Suspicious fires typically require lengthy investigation before it can be determined whether the measurable behavior constitutes the offense of arson; in white collar offenses such as embezzlement and some types of fraud, it may be impossible to pinpoint exactly when the offending behavior occurred, and the earliest point at which the “crime” might be ruled to constitute an offense is either at the point of arrest or the filing of legal charges. In still others, such as corruption, bribery, and some intellectual property offenses, the best or only time for determination and measurement is later still, upon resolution through settlement, plea arrangement, or conviction.

Reconciling the time of occurrence of a crime can be very messy—all the more reason, as suggested by Conclusion 2.1, to take care to position crime statistics as estimates and not as authoritative point-in-time enumerations.

2.2.2 Putting Crime in Context, Alternative Metrics for Crime, and the Harms Imposed by Crime

A recurrent theme throughout our panel’s work is that modern crime statistics would be more useful if they can provide more information and more

SOURCES: Adapted from President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice (1967:8–9) in 1997; posted at http://www.bjs.gov/content/justsys.cfm.

flexibility for detailed analysis than simple counts and summaries alone. In the next section, we turn to the specific data collection systems that we expect to populate national crime statistics going forward, Two important points should be made about information that it is supplementary to traditional measures of crime. The first is that users can only draw meaningful conclusions from comparisons of crime data across jurisdictions or across time if they have the information necessary to put crime in appropriate geographic, demographic, and other context. This is one reason for the attributes that we include as a part of our proposed classification, but the argument extends beyond that. Part of national crime statistics going forward should be ready provision of applicable noncrime data that can be used, side-by-side and in concert with levels of crime (however offenses might be measured), to draw effective conclusions. This issue, including the work of a Crime Indicators Working Group commissioned by the Bureau of Justice Statistics, is discussed in more depth in Section D.3.

The second essential point is that entirely different measurements—not just trying to quantify the occurrence of crime—may be most useful or salient to understanding crime. These alternative metrics may include estimating the harm done by or the cost of crime. In defining “crime” in Section 1.2 of Report 1, we noted that “there are other measures related to offense behaviors (such as estimates of damage or financial loss inflicted, or even the perception of victimizations or occurrences) that may have greater salience” than counts for some offense types. We broadened that concept in the last sentence of Conclusion 2.1 in this volume, arguing that new and detailed crime statistics should “provide the raw material for more useful measures related to an offense (such as the harm it causes) in addition to its count.”

Harm is inextricably linked to crime. In Report 1, we took as a basic behavioral definition of crime that it is “a class of socially unacceptable behavior that harms or threatens harm to others,” and this behavioral definition was the basis for all the ensuing specific definitions of offenses in our classification. To make that definitional task tractable, we had to treat harm as a binary, yes- or-no concept—as, for example, in drawing a sharp and observable difference between “assault” and “threat” being the actual infliction of bodily injury, or by resorting to “unlawful” as the criterion by which to indicate whether a toxic substance is sufficiently harmful as to be branded an “environmental offense.” There are a few exceptions to this treatment of harm as a binary indicator for definitional purposes. For example, our revised assault category also includes a definition for serious bodily injury to facilitate a distinction between minor and serious assault, and our breakdown of category 6, controlled substance offenses, is premised in part on the quantity of drug involved (and so the amount of harm that could be wrought).

The point of this current section is to emphasize that harm is not binary, and that the measurement of harm associated with crime is an important consideration in its own right. Yet it is also true that measuring the harm

associated with crime is both difficult and contentious—a major research effort in its own right, and one that might not be a cleanly resolvable problem. As this report was in final development, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (2017) issued a report summarizing its findings from a survey of 16 experts on estimating the cost associated with crime, summarizing several approaches and corroborating the lack of agreement on a best approach to the problem.

Although efforts to measure the costs of crime are known to be challenging, there are critical reasons for encouraging these efforts. Crime and societal responses to crime result in substantial costs to the nation. Adequate measures of the harms from crime and victimization are necessary for evaluations of some crime control policies (Greenfield and Paoli, 2013; Paoli and Greenfield, 2015). These types of measures are critical for establishing policy priorities across a wide range of offense types. They would also allow for evaluations of policy effectiveness for specific offenses, as well as better accountability from agencies charged with responding to crime. To achieve these important goals, research and development of estimates of the harms and costs of crime are essential.

In this report, we are very sparing in formally designating conclusions and recommendations. We offer many suggestions along the way but have preferred to keep the formal-language focus on a small number of main conclusions. Alternate metrics of crime should be an important part of a modern crime statistics system that is not limited solely to offense counts, but full exploration of the alternatives is simply not possible in this study with its already expansive mandate. This concept is sufficiently different from the other guidance in the report that we think it appropriate to designate it as a formal conclusion, as follows:

Conclusion 2.2: There is a problematic lack of solid information about the relative magnitude of the costs, harms, or importance across crime offense types or specific incidents. Further research could be sponsored on estimating the magnitude of societal harm associated with the major categories in the proposed classification—ideally, in a way that facilitates comparison over time and offense types.

Offense counts alone are almost certainly not the correct measure of crime and, as we have already noted, the new types of crime in our classification in particular (but also some of the traditional offenses) will require further, dedicated thought regarding the most appropriate and accurate measure of level or trend—whether report to law enforcement, report to a survey interviewer, arrest, conviction/ruling/imposition of sanctions, or the like. It will necessarily take some trial and error to develop the right mix of such indicators. It will also take time to determine the kinds of alternate, auxiliary measures that may add much to national understanding of crime.

2.2.3 New Systems for New and Traditional Crimes

The second main message of this report builds directly from Conclusion 3.1 in Report 1, in which we concluded that:

No single data collection can completely fulfill the needs of every user and stakeholder, providing data with sufficient detail, timeliness, and quality to address every interest of importance. Any structure devised to measure “crime in the United States” should necessarily be conceptualized as a system of data collection efforts, and informative details about the collection and quality of the distinct components in this data system should be included to help ensure proper interpretation and use of the data.

Specifically, it reinforces the system-of-systems concept for a modern crime measurement infrastructure, stipulating a continued role for the current core methodologies but vitally extending them as well. Thus, we reach the following conclusion:

Conclusion 2.3: Improvement in the nation’s crime statistics will require enhancements to and expansions of the current data collections, as well as new data collection systems for the historically neglected crime types highlighted by the proposed crime classification.

In practice, this means that the set of output crime statistics expected from a new crime data infrastructure should strive for uniformity in concept and underlying definition—so as to permit detailed analysis and comparison (in appropriate context) across jurisdictions and over time. But the statistics need not be completely uniform in mode of measurement for all offense types, depending on what is deemed to be the most effective means to measure the requisite information about specific offense categories. The dual statement to the argument that “no single data collection can completely fulfill all needs” is that no single data collection should fulfill (or be made to fulfill) those needs, either. Specifically, the three component data systems that we envision are:

- an incident-based recording system covering offenses known to law enforcement agencies;

- a survey data component, principally the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) and its topic supplements, but also including other surveys as appropriate, including an emerging BJS survey intended to improve the measurement of the specific offenses of rape and sexual assault (see National Research Council, 2014); and

- a variety of primarily administrative-record-type data sources, primarily for coverage of new crime types that are outside the scope of either police-report or household survey methods.

In Report 1, we also argued (Conclusion 5.4) that:

Full-scale adoption of incident-based crime reporting by all respondents or sources, that is sufficiently detailed to permit accurate classification and extensive disaggregation1 and analysis, is essential to achieving the kind of flexibility in crime statistics afforded by a modern crime classification.

The phrase “all respondents or sources” is included precisely because multiple component systems are necessary within a broader, new crime statistics infrastructure. As we note below, this language can fairly and accurately be read as strong support for the National Crime Statistics Exchange (NCS-X) initiative and progress toward full-scale implementation of NIBRS, as well as the basic structure of NCVS interviews (eliciting incident-specific detail from its respondents). In both the survey and administrative-records setting, the precise application of the attributes or contextual tags specified as part of our classification will depend on the specific crime because not every attribute is necessarily meaningful or appropriate for every possible offense. But the spirit of the conclusion remains the same: The key point is to avoid the sole collection of monolithic counts, as in the UCR Summary system, and collect detailed incident-specific data to the extent practicable.

New System for Police-Report Data: NIBRS as First But Intermediate Step, and Switching from Reporting to Recording

The first major component of the modern crime statistics infrastructure we recommend is an incident-based recording system covering offenses reported to or otherwise known by law enforcement agencies. The basic nature of crime is such that police-report data will continue to be an essential resource. Indeed, it will be the principal source of statistical series on the traditional crimes identified in our classification, as well as a good percentage of the new crimes. This data system could also be characterized, as we did in Report 1, as being “attribute-driven,” referring to the set of attributes or contextual tags that we posited as constituting an essential part of our recommended classification and a minimum level of detail desired for eventual disaggregation and data analysis.

We strongly support the BJS’s National Crime Statistics Exchange (NCS-X) initiative, NCS-X’s cultivation of a nationally representative sample of NIBRS-reporting jurisdictions, and the sunset of the UCR Summary Program in favor of a fully operational and full-compliance NIBRS. But there are two principal reasons why we did not simply designate NIBRS as the first piece of our envisioned modern data infrastructure.

___________________

1 By “disaggregation,” we refer to having more than aggregate summary counts for individual categories, but also making use of the attribute/contextual information included in our classification to permit use-driven breakdowns of offenses and incidents into more meaningful analytical subsets.

The first is that even a fully realized NIBRS is not enough to provide necessary information on crime and to reconcile key conceptual mismatches. In closing Report 1, we described NIBRS as an “intermediate step” in getting to the kind of data collection that we desire, intermediate because the nation’s comprehensive picture of crime would be incomplete even if full NIBRS participation were achieved today. However, the conclusion that the picture is incomplete because of the sheer scope of covered offenses between our proposed classification and NIBRS would be mistaken. We intend for police-report data to be the principal source for those offenses for which those data and that methodology are the most apt—not the entire classification. Moreover, as described in Report 1, we deliberately limited the attributes (contextual information) that are part of the data collection to things that are relatively easy to determine objectively and quickly—and, pointedly, to keep attribute data collection at roughly the same level of effort required to assemble NIBRS’s data elements. Hence, in reconceptualizing police-report crime data collection, we have tried to keep the request realistic—some expansion of covered offenses relative to NIBRS, to be sure, and some revision of attributes/contextual elements. But, going forward, the principal substantive limitation with NIBRS relative to our suggestions is the major difference in general concept and definition for some major offense types—the things that led us to conclude only a “partial match” between our classification and NIBRS coverage. In developing our classification, we reached the firm conclusion that the UCR/NIBRS concept of aggravated assault is fundamentally flawed and that better information would be generated by retooling the concepts of assault and threat; likewise, the basic differences in concept concerning other crime types, such as sexual assault, harassment and stalking, and fraud, among others, are such that a complete NIBRS only provides part of the information that the nation needs.

The second reason for not stopping with NIBRS is that—mindful of the voluntary nature of police-report data—the timing is right to fundamentally change the focus of police-report data from reporting to recording, from preparation of specialized products to direct transfer of data as a seamless by-product of normal operations. The goal of mounting a voluntary data contribution system that is effectively an invisible by-product of day-to-day local police agency operations, requiring minimal if any direct effort, was simply not attainable in the era of the UCR Summary System. Under the guise of providing simple summary counts, the process of completing and submitting the monthly Return A and Supplement to Return A required a very intricate bookkeeping system—effectively maintaining ledgers of offense tallies, arrests, clearances of arrests, property of stolen goods and so forth, not to mention the filing of supplemental returns (e.g., a −1 and a +1 to account for a serious assault converted to a homicide by the death of the victim). Meanwhile, the cognitive and processing burden of ensuring compliance with UCR definitions and concepts

was placed squarely on the local law enforcement responders themselves, making completion of even the “simple” Return A by a smaller agency (without a robust automated information system) a potentially overwhelming task.2

We are mindful (from Appendix B’s historical review) that, from the outset in 1930, planners of national crime statistics have frequently severely underestimated the extent, quality, and ease of conversion to requested data formats of local law enforcement agency records, and we do not make such an assumption casually now. Also, there is certainly variation across agencies in the expected rigor and format of officers’ reports (and the extent to which officers are actively trained, or not, in report writing), including the possible role of those reports in downstream local and national crime statistics. Finally, sensitivity also exists because a “finished” officers’ incident report may actually still be a “live” investigative record—all factors that may affect the quality of reports entered into a local agency’s records. Yet at the same time, that first responder’s report may be the first or best chance at ascertaining such factors as bias or “hate crime” motivation in an incident, or accurately capturing other attributes of a particular offense.

We will return to these critically important issues in Section D.1 (Appendix D), in which we delve into them in depth that would otherwise disrupt the flow of argument here. All that said, our interactions with a wide variety of crime data stakeholders and local law enforcement officials strongly suggest that the days of local police records being hard-copy paper reports stored in file cabinets are numbered, if not over. The pervasiveness of automated information systems in usage by law enforcement agencies, for support of all functions from officer dispatch through the investigative process, was something that was underestimated by NIBRS planners in the 1980s and 1990s. In 2017, as we understand from our discussions with agency practitioners, it has become the norm for all but a very few local law enforcement agencies. Technological advances enable the long-hoped-for vision of a data system premised on direct transfer of records to state and then to national repositories, shifting much of the burden of editing, standardization of concept, and ensuring data quality to the state and national levels.

Survey Data as Essential, Complementary Measures

Self-report, survey information on criminal victimization—including but not limited to an adequately resourced NCVS—should also remain a pillar of U.S. national crime statistics. Survey data on crime are necessarily limited in the degree to which the resulting data can be disaggregated along useful analytical

___________________

2 Our workshop-style meetings turned up multiple NIBRS-reporting jurisdictions that had encountered an unexpected handicap: Their records management systems turned out to be incapable of directly computing UCR Summary Return A files. Instead, they had to rely on their state UCR coordinators to translate their incident-based files into Summary format.

lines. This is because crime is still, relatively speaking, a rare event in the population at large, so the survey’s sample size would have to be unworkably large to support fine-grained estimates. But survey data should remain part of the crime statistics infrastructure because of their unique, conceptual strength—the ability to estimate the level of victimization that is not reported to law enforcement authorities. Survey-based measures can never, without prohibitive cost, achieve fine detail in both offense coverage and geographic/demographic group; their province will continue to be relatively high-frequency offenses and for relatively coarse population subgroups and at relatively low frequency (e.g., annually). But the value of an independent source of victimizations not reported to the police—as a check on estimates derived from either police-report data or administrative/external files—makes survey measures a vital part of the statistical infrastructure.

Accordingly, survey data are poised to serve most often as secondary measures of offense categories or groups of offense categories. However, it is entirely possible that, as individual offenses are reviewed for the most appropriate mode of measurement, the most salient and meaningful national statistics on some offense types may turn out to be NCVS-based measures (at the expense of geographic disaggregation). An iteration of the Identity Theft Supplement to the NCVS yielded estimates suggesting on the order of 16.6 million adult U.S. residents experiencing one or more incidents of identity theft in 2012—incurring estimated monetary losses on the order of $25 billion (Harrell and Langton, 2013). Tellingly, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) partnered with BJS on the supplement (along with the Office for Victims of Crime)—in part, undoubtedly, with interest in calibrating the results with experiences reported to the FTC’s fraud hotlines and in its own data collections. Other offenses for which survey methods might turn out to be most salient include other forms of consumer fraud (such as credit card theft) and experience with public nuisance–type crimes; perception-based measures via the NCVS or supplements might be preferable, on balance, to counts known to be poorly reported to law enforcement.

For several years, BJS has been pursuing several different tracks for overcoming the NCVS’s limited capacity for subnational disaggregation. The first is a direct approach: deriving estimates for selected subnational populations consistent with the sample design (the largest of states or metropolitan areas) where there is sufficient sample (pooling multiple years of data as needed), and trying to selectively boost sample size to make more such direct estimates possible. A second approach is indirect: combining existing victimization survey data, existing UCR police-report information, and a variety of community and household statistical information to develop statistical models for victimization of particular types. And a third combines some elements of the other two: effectively defining subnational strata to combine NCVS sample data (and thus

develop direct estimates) for groups of places that are similar to each other along particular geographic/demographic lines.

Going forward, to strengthen the survey-based component of the crime data infrastructure, methodological and development work should continue along the lines just described: continuing work on NCVS supplements (or additions to the main survey) on offense types for which survey measures of perceived victimization might have particular weight (including fraud, identity theft, and stalking/harassment) and the refinement of subnational estimation techniques in the NCVS. It is also important that BJS’s work on a parallel survey on rape and sexual assault (as recommended by National Research Council, 2014) continue, recognizing the special difficulties of accurate measurement of those sensitive crimes. Another area for ongoing NCVS improvement is to make fuller use of NCVS interviews, including those with households that do not have victimization incidents, to generate data on the community context of crime; this will be discussed further in Section D.3 (Appendix D). The NCVS has to be properly resourced in order to fulfill its core mandate to measure levels and change in crime victimization over time with acceptable levels of precision, much less meet additional demands. The survey approach is too essential a complement to (and a check on) police-report and other crime data to let languish.

New System (Primarily) for “New” Crime: Administrative and External Data

For the “new” offenses in particular, reference to either police report or victimization survey data is likely not the best or most accurate approach to get a sense of levels (both counts and characteristics) and trends in specific offenses. Hence, new systems will be necessary to begin to develop estimates in top-level categories 6–11 in our classification: a crime statistics clearinghouse function to obtain and compile data from external resources including other federal or state agencies. In many cases, this information will be administrative record-type data extracted from the information files of agencies or organizations outside of the police and law enforcement structure. These may include regulatory agencies at the state or federal levels, the courts and other judicial entities, and other public health or welfare agencies. As noted in introducing Section 2.2.3, and consistent with our guidance both here and in Report 1, the objective in marshaling this variety of data is to achieve as much uniformity (across reporting entities) in underlying concept/definition as possible—and as much capacity for disaggregation and reanalysis by attribute/contextual information as is practicable.

This suggestion is more demanding than an ambitious recommendation made by our predecessor National Academies panel to review the full suite of BJS programs. That panel urged BJS to “document and organize the

available statistics on forms of crime not covered by” current national crime data series, and to “strive to function as a clearinghouse of justice-related statistical information, including reference to data not directly collected by BJS” (National Research Council, 2009:Rec. 2.1). Our suggestion is not simply to link or refer to external data but to actively assimilate them within national crime statistics. We recognize the task to be difficult and intricate to implement, but necessary to proper understanding of national and subnational crime problems.

Use of alternative data resources is necessary because there are many crime offense types for which neither police-report data nor survey data are apt or workable as a source of offense counts and characteristics. One obvious example would be crimes against government and business that are not specifically spatial in a way that is linked directly to a local police jurisdiction. If a particular convenience store is robbed, the local police will likely be contacted; if a corporation’s intellectual property is stolen by hackers attacking from overseas, the local police will not be involved. Indeed, the corporation may not notify any policing agency (local, state, or federal) to avoid reputational damage done by public acknowledgment of its victimization. There are many other reasons that police report and victimization survey data are inherently limited in what they can provide. For example, local law enforcement—traditional police—may not have true jurisdiction relative to other regulatory agencies, such as environmental offenses that would be reportable to state or federal environmental quality authorities. Relevant information on offenses may also be collected by law enforcement agencies that have not typically been thought of as integral to crime reporting (e.g., welfare fraud or other fraud against government agencies, which may be known or reported to state or federal offices of inspector general). For still other offense types, law enforcement officials may not be seen as a relevant or natural point of contact—the quintessential example being fraudulent credit card transactions, in which customers’ first and likely only point of contact might be their credit providers.

Conceptually, the challenges of brokering access to alternative, external data resources and processing them loom large—much less marshaling them into a description and assessment of crime offenses from multiple, disparate data sources and providers. Establishing data-sharing arrangements and memoranda of understanding to facilitate them is frequently a difficult chore, even between units of the same federal executive branch agency. Here, the problem is complicated further by seeking information to populate crime statistics from agencies that may view their role as strictly and exclusively civil or regulatory in nature. Entities such as the Securities and Exchange Commission, Federal Trade Commission, Federal Communications Commission, Environmental Protection Agency, U.S. Postal Inspection Service, and numerous inspectors general may—perfectly validly, for their operations—think of their work as cases, complaints, investigations, violations, infractions, or the like, and not

really as offenses in the sense of crime. So, to the extent that they see their work relevant to crime statistics, it might be at a very late (resolution) stage—the proffering of criminal charges or formal referral to law enforcement/criminal justice processing. Thus, there may be resistance to sharing or documenting data that strike them as fundamentally preliminary, if related at all, to crime occurrences.

Crime is sufficiently complex that it will require the use of nontraditional data sources and methods in addition to the sources and methods currently in use. The underlying issue is to identify the best way to combine, merge, extract, and analyze administrative-type data from a multitude of agencies and providers, preserving the necessary amount of analytic detail while preserving the privacy of individual persons or other entities represented in those data. Full consideration of these issues is beyond the scope of this panel; indeed, it is the province of the Commission on Evidence-Based Policymaking (2017) mandated by Congress via P.L. 114-140, which issued its final report on September 7, 2017, as well as another National Academies panel tasked to review the use of multiple data sources in federal statistics (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2017a,b).3

What is clear is that it is necessary to turn to sources other than police report or victimization survey data to get a more appropriate picture of all crime, and that overcoming the procedural/implementation difficulties will require great effort. To achieve this, the “national” role in “U.S. national crime statistics” will have to be more than a relatively passive aggregator/compiler of data in order to be worthwhile and successful. We return to this point throughout Chapter 3.

2.2.4 Using the Crime Classification as Blueprint

With a next formal conclusion, we return to the issue of crime in crime statistics, the scope of anticipated collection, by emphasizing the importance of maintaining a classification of crime as the foundation for national crime statistics collection.

Conclusion 2.4: The classification of crime for statistical purposes recommended in Report 1 should be used as a blueprint for the nation’s crime statistics. It should be used to guide revised measures of crimes currently included in existing data as well as pilot/initial data collection of as-yet-unmeasured crime types—even though it is impossible today for data collection to include every crime in the classification. While it is imperative that the classification undergo

___________________

3 James Lynch, of this panel, was a member of this separate National Academies Panel on Improving Federal Statistics for Policy and Social Science Research Using Multiple Data Sources and State-of-the-Art Estimation Methods, also organized by the Committee on National Statistics.

regular update and revision, initial data collection should begin with this as a base, rather than continue to refine the classification in the absence of data.

Our crime classification attempts to be comprehensive of all crime that occurs, not just that which has traditionally been counted, and it is understood that not every element may be measurable either at the outset or in the near future. It is critically important that the resulting sparseness of the match between our proposed classification, NIBRS, and NCVS be taken as an opportunity for improvement rather than as proof of the impossibility of the task. We considered but ultimately decided against attempting a delineation of highest-priority offenses to measure or, conversely, the ones that will remain aspirational for years. Even if such a comprehensive ranking were possible, we concluded that such a ranking would be inconsistent with one of the basic principles of the classification itself. All of the categories and subcategories have some baseline level of importance. Hence, artificially casting a handful of offense types as most important would seem akin to reprising the UCR SRS’s fundamental flaw, putting disproportionate weight on a few select “Part I” crimes and rendering everything else comparatively invisible.

A central observation that follows from interpreting the classification as a framework for understanding the scope of all crime is simply stated but fairly revolutionary for U.S. crime statistics: Any tabulation that wishes to claim to present a comprehensive view of crime in the United States must pay serious attention to categories 6–11 in our classification, commensurate to that given to categories 1–5.

The success of modernizing the crime data infrastructure depends on the extent to which the participating stakeholders accept and endorse the model. Acceptance of the crime classification and the resulting statistics can only occur if the classification is used to generate those statistics. That use must begin somewhere, with trials of prototype measures and phased-in implementation. What is most urgently needed in areas like the various major types of fraud, environmental offenses, or more routinized measures of interference with computer networks is a start—the derivation of measures to at least get these crimes and their measures into the same national conversation about crime in the United States as robbery or assault.

The recommended classification of crime should be considered organic and evolving, and should be revised over time to keep up with stakeholder needs and the changing nature of crime itself. There is ample precedent for a structured assessment process, such as those that inform periodic revisions of the International Classification of Diseases or U.S. statistical classifications of industry and occupations. Similarly, we understand that the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, whose expert working group developed the International Classification of Crime for Statistical Purposes (ICCS) upon

which our proposed classification is patterned, is establishing a standing technical advisory group to assist with implementation and update the ICCS. This is another example that might be considered in formalizing an update process for a U.S. crime classification. But the point we make in the last clause of Conclusion 2.4 is that the classification—like any new structure—needs to be examined and evaluated in practice, through the collection of real data.

The need for reassessment and revision, based on collected data and experience in their analysis, applies to the categories of the classification, its associated attributes, and the specific statistical measures that result from the classification. It is not difficult to find points on which categories or attributes in the proposed classification might be constructed differently. Should hazing be considered separately from other acts that endanger the life of another human (as in category 2.8.1)? Is shoplifting sufficiently different in nature or volume that it should be distinguished from other thefts from businesses or organizations? In the example of ransomware mentioned earlier, is there good reason to carve out a separate category for that particular offense of computer-enabled extortion? In the electronic age, should poor or negligent data stewardship—as in the 2017 data breach involving the credit agency Equifax—be considered a crime of negligence, even though such offenses have typically been limited to negligent acts involving the threat of bodily physical harm? Going beyond individual fine-grained categories, different groups and different stakeholders might reasonably develop completely different classification structures for major offense categories—see, for instance, the extensive taxonomy of fraud developed by Beals et al. (2015) and outlined in Box 5.1 in Report 1. Likewise, in considering the meaning of statistics on things like cybercrime, stolen credit card information, and environmental offenses, analytical paralysis could settle in trying to converge on the ideal measures that should accompany and give meaning to offense counts—whether amount of pollutant released, number of downstream users affected by a computer virus, number of attempts to open credit lines with stolen identity information, or the like. The classification can and should change, and measures associated with it can and should change correspondingly, but that cannot happen productively until initial, prototype numbers are produced and scrutinized.