9

Important Messages and Potential Next Steps

In two of the workshop sessions, presenters and panelists discussed the important messages that had emerged over the course of the workshop and potential next steps. Those two sessions are summarized in this final chapter to revisit earlier ideas, extend those ideas, and point to possible future directions for discussion and action.

The first session was a “fishbowl” panel discussion, introduced and moderated by Philip Grossweiler, principal consultant for risk management, LNG Projects, M&H Energy Services, on barriers to effective systems for taking action and reporting when hazards are observed and on how safety systems for taking action and reporting hazards can be improved. The panel members were

- Chris Beckett, former chief executive officer (CEO) of Pacific Drilling;

- Jody Broussard, president, Prime Resources Management Group, LLC;

- W.R. (Rick) Farmer, managing member, Double R Engineering, LLC;

- Lautrice (Mac) McLendon, general manager, safety and environmental Gulf of Mexico, Shell Oil Company;

- Hung Nguyen, chief operating officer, Meridian Global Consulting LLC; and

- Ajay Shah, team lead, Gulf of Mexico Business Unit, Chevron, and lead, Human Performance Working Group, American Petroleum Institute RP 75.

The other session, which was introduced and moderated by Richard Sears, professor in the Department of Energy Resources Engineering, Stanford University, was on lessons learned from the workshop and featured the following panelists:

- Najmedin (Najm) Meshkati, professor, University of Southern California;

- Rhona Flin, professor of industrial psychology, Aberdeen Business School, Robert Gordon University;

- Joseph Leimkuhler, vice president, drilling, LLOG Exploration LLC;

- Michael Fry, president and CEO, Deepwater Subsea LLC; and

- Lautrice (Mac) McLendon, general manager, safety and environmental Gulf of Mexico, Shell Oil Company.

PROBLEMS AND POTENTIAL LESSONS LEARNED FROM THE WORKSHOP

The offshore oil industry is complex in complex ways, said Sears: “These are very complex engineered systems that we manage with even more complex human systems. And all of that is embedded in a natural system that is far more complex and that we know very little about. That is the fundamental challenge of what we’re trying to do.” The purpose of the Gulf Research Program (GRP) is to study these complex systems by sponsoring research that is not being done by others, he continued. He added that the industry is conducting billions of dollars worth of research every year, and the GRP is not going to reproduce that, nor is it going to do research that the regulators of the industry ought to be funding. Rather, he elaborated, the GRP is interested in what is already happening, what is not happening, and how the gaps can be filled.

Sears observed that many organizations, including the Offshore Energy Safety Advisory Committee, the Oil Spill Commission, and committees of the National Academies, have made recommendations that involve safety in the offshore oil industry. For a time, he added, the entities responsible for offshore safety, including the industry and regulators, were “inundated with recommendations,” and as a result, implementation of the recommendations has been slow. He noted that the National Oil Spill Commission created a website (http://oscaction.org) to track and help implement the commission’s recommendations and that the legislative branches of governments typically got Fs and Ds in implementation, whereas the industry, regulators, and executive branches typically got Cs and high Ds. “There’s been a lot of disappointment,” he said.

On the other hand, Broussard said he was impressed and encouraged by what he had heard during the workshop. “We talk about the bad stuff,

and we should honor the guys that have fallen—it’s important that we don’t forget them. But we are doing some things right,” he said. He cited as an example the expanded use of stop-work authority, which works well as long as people are able to use it.

Shah agreed, pointing out that the workshop was not designed to focus on things that have been getting better. “This is a human condition,” he said. “We remember what is more visible when things go wrong. . . . But we don’t do a good job as people or as an industry learning from what went right.” Many workers are empowered today, he stressed, even if they are not empowered in all the ways they need to be.

Shah also pointed out that stories about workers who lost their jobs when they exercised stop-work authority tend to be passed around, but “you never hear about the people who don’t” lose their jobs. While the industry is obviously not perfect, he observed, people do exercise stop-work authority and are not punished for it. Then again, he acknowledged, if people believe they will lose their jobs, they may be less likely to act.

Finally, Peres noted that the offshore oil industry is used to doing difficult things, so it has the capability to improve safety.

CULTURE AND LEADERSHIP

Beckett pointed to two pillars that need to be established to enhance safety in the offshore oil industry: first, the industry needs to have a culture that encourages and empowers the workforce, and second, the culture needs to embody the discipline to follow procedures but be sufficiently open to feedback so that procedures can be improved. The task is complicated, he added, by the fact that cultures differ from place to place—say, between America and West Africa. It is also complicated, he argued, by old-school attitudes that workers are hired to do as they are told.

Meshkati elaborated on the role national cultures can play on drill rigs. He asserted that the importance of culture requires examining the interactions of national cultures with the culture of companies and the cultures of individual rigs. In particular, he argued, these cultures can have a major effect on worker empowerment.

Broussard reminded the group that in a workforce consisting largely of contract workers, it is the responsibility of contractors to ensure that they know their customers well enough to put the right people on the right jobs. For that reason, he stressed, it is the responsibility of contractors to make sure their employees are competent in their jobs and the operator’s responsibility to verify their competency. In Broussard’s opinion, job competency is a major factor in employee empowerment and employee safety.

One way to change the culture is by changing the leadership team, Beckett observed. For example, he advocated for a broadly representative

leadership team in which everyone has clearly defined responsibilities plus a collective responsibility for the entire operation. The idea, he said, “is to change the culture to be collaborative, to be open to new ideas, the recognition that you don’t know everything.”

Shah concurred that worker empowerment needs to be embraced by leadership and become part of the value proposition of a company. “People who want benefits don’t always understand the cost and then say, ‘Well, cost is not an object. This is safety,’” he observed. “But our industry does not make money on safety. We make money on safe operations, so you have to understand the value proposition of anything you do.” That value proposition also needs to be conveyed to regulators, Leimkuhler added.

Change is not necessarily difficult when a person wants to change, noted Sears. The important questions, he argued, are what motivates people and what their values are. Leaders then need to convey the personal value proposition to create change, he asserted. He added that change also needs to be an inclusive process among stakeholders in all sectors and locations, emphasizing that a few people cannot impose change on the industry and expect good results.

In response to a question about the economic pressures on the industry, Beckett identified the greatest challenge for leadership in the industry as the pressure from shareholders and Wall Street. A strong board can balance that pressure and help the leadership make decisions that look beyond the next fiscal quarter, he stated, adding that good regulations also can have that effect: “If there is a legal regulation in place that requires you to do something that is explicitly for the benefit of the long term and has a short-term cost, you are going to get some protection from that.”

The offshore oil industry has done things the same way for a long time, noted Fry. Changing the long-standing culture of an industry can be difficult, he acknowledged, but mindsets can be changed.

LESSONS FROM ELSEWHERE

Sears expressed the view that the offshore oil industry can learn a great deal from other industries, including the airline industry, health care, the nuclear power industry, and the railroad industry. He pointed to the airline industry as being very similar to the oil industry: it is a commodity-driven business; a number of different airframe manufacturers, large and small, must integrate with a number of engine manufacturers, large and small, as well as with electronics manufacturers, large and small; and it is a cyclic industry with a federal regulatory authority. “This notion that somehow our industry is harder than that, I just don’t get it,” he said.

Grossweiler observed that the aviation industry has been rigorous in developing and following good procedures, which requires good resource

management and organizational development. He stressed that the aviation industry also has engaged in continuous improvement by making itself into a learning organization, which requires gathering and acting on information from across the industry.

Peres cited an example of the oil and gas industry learning from other industries: the organization called Pumps and Pipes, which brings together people from the oil and gas industry, medicine, and NASA to talk about problems they face in common. The perspective today is largely that of mechanical engineering, she noted, but it could be extended to human factors. She suggested further that the academic discipline that specifically examines the consequences of human factors for safety in complex sociotechnical systems has much to contribute. This area of research “is going to be as complex as the systems themselves,” she said, “and we will need to be ready to break things down to build them back up.”

Finally, Nguyen pointed out that other offshore incidents involving cruise ships, cargo ships, and other vessels have many parallels with incidents occurring on offshore oil platforms.

PROCEDURES AND EMPOWERMENT

A major topic of discussion was how to balance the need to follow procedures with the autonomy that is part of empowerment. McLendon expressed the challenge thus: “We have come so far in order to get approved procedures in our industry that I would hate to see us go back and say, ‘A person doesn’t have to follow procedures. They should be empowered to slow down, shut down, stabilize, and get the right procedure before advancing.”

Shah raised the point that most accidents are not malicious in nature; they occur because people do not have the knowledge, skill, or ability to make the right decision. He added that people make the best decisions they can with the resources available to them. The question, he said, is, “How do you help everybody make better decisions?” He noted that the distinction between personal safety and process safety factors into this issue. According to Shah, stop-work authority is much easier to exercise for personal safety. For example, he said, failure to wear personal protective equipment is easy to see and subject to black-and-white rules, yet even in this case, many infractions, such as walking down a stairway without using the handrail, go uncorrected. Process safety is more difficult to see and enforce, he continued. A worker may have a gut feeling that something is wrong, he observed, yet that may not be enough for the worker to take action.

Broussard emphasized that workers need to be empowered enough to know how to do a job and do it safely: “We have to empower our people enough to be comfortable with personal safety so they are also comfort-

able making decisions about process issues.” McLendon added that one thing Shell did to emphasize the importance of stop-work authority was to create a recognition program that rewards workers for exercising their stop-work authority.

Farmer identified training as a major issue. He pointed out that pilots have many hours of training, but asked, “How much training are we providing our people?” One way to gauge these issues, suggested Meshkati, would be through “leading safety indicators,” which are common in other industries.

Beckett pointed out that part of the challenge is to empower people not to have to do certain things. He stressed that decisions need to be made in the right place. With the Macondo incident, for example, decisions were made on the rig that would have been made differently onshore, he argued. According to Beckett, ensuring that decisions are made where they need to be made could provide protections for offshore leadership, who would no longer have to make decisions that should have been made elsewhere.

Beckett also asked whether the human-systems interface is in the proper location. “There are some things that people are very good at,” he pointed out, “and some things that some people are not very good at.” Not much is automated on drill rigs today, he added, but there are some things that could be automated to improve both personal and process safety.

Middle management is often seen as a bottleneck for change, noted Sears. Senior managers say, “We have these great ideas, but we have a hard time getting them through the middlemen,” he observed. Front-line workers say, “We have all these great ideas, but we have a hard time getting them up through middle management.” But in a sense, he said, virtually everyone in the offshore oil industry is a middle manager. “Middle management is where the reality of what happens in the field has to interface with the vision of what happens in an office somewhere,” he said. “Whatever our job title is, we all have to interface between some vision above, whether it’s the board or the shareholders or somebody else, and the reality below.”

In response to a question from Flin, Broussard acknowledged that managers, not just front-line workers, also need to be empowered. “That’s definitely a gap in our organizational structure in most of our service companies, and in most of our operating companies,” he said. Part of the issue, he noted, as pointed out earlier in the workshop, is the tradition of promoting people on the basis of craft rather than leadership. Also, he argued, managers need more training in soft skills. “We need to change some of the ways we are training and advising our managers,” he said. “That’s how you empower them and give them the information to do a good job.”

GENERATING AND DISSEMINATING DATA

The role of data in improving safety and enhancing worker empowerment was another prominent topic of discussion. The aviation industry has demonstrated what can be done with data gathered from on-the-job experience, said Flin. She suggested that increased amounts of data could be gathered from the offshore oil industry and combined with existing behavioral science data to improve training and leadership programs throughout the industry. She added that new approaches and new kinds of data also could produce major advances. As an example, she cited the possibility of gathering data on the extent to which workers feel they have stop-work authority from interviews or confidential surveys. She noted that outside funding could be leveraged with matching funds from the industry, perhaps through a collaboration among companies, to produce information of widespread value.

Beckett pointed out that a considerable amount of data already exists if they could be accessed. “We get hundreds of report cards off every rig every month,” he said, “and they are studied throughout the drilling contractors individually. But fear of legal ramifications or exposing the company to some sort of litigation is the reason they don’t get shared beyond the company bounds.” He noted that processes for placing this information in some kind of database are being discussed, but added that protections will be needed to make that happen.

Farmer made a similar point, noting that offshore operators already meet to exchange information among themselves about what is and is not working. “They meet in rooms just like this, no reporters, no BSEE,” he said. The problem, he suggested, is that if information was brought to regulators, they would want to write new regulations.

Nguyen asked whether the right information has been gathered even post-Macondo. He suggested that, as noted by other speakers, the industry continues to focus too much on personal rather than process safety. He added that different vessels (ships or marine facilities) also have different requirements. “You have to look at the data, and you have to look at the system,” he asserted. “The system is not there yet in terms of reporting requirements.”

Shah pointed out that managers on offshore rigs already spend a great deal of time on paperwork, some required by their companies, some required by regulators. Thus, he suggested, one problem with an increased reporting requirement is that less data will be available because people will not have enough time to generate the data. For data to be usable by the people who need the data offshore, he argued, a balance needs to be struck to produce a system that is simple, quick, and limited. “Yes, you would give up a lot of analytical capabilities,” he acknowledged, “but in turn you

might get more data.” Farmer added that even when people can gather data, reporting is an issue because as soon as they get off a rig, they head for home after being away so long.

Shah expressed the view that analysis and simplification are also necessary to get information quickly and cogently to the people who need it to make decisions. The same thing occurs with a fighter pilot who needs critical information to carry out a mission, he observed. “The speed of communication has increased, but the speed of thought has not,” he said. He argued that getting the right information to the right people at the right time is how the industry will get better.

Referring to his proposal to create a program for the offshore oil industry based on the Aviation Safety Action Program (ASAP), Leimkuhler emphasized that limits on the availability of the data are an essential part of current reporting and follow-up systems. He also pointed out that the system used by the airlines as part of the ASAP he has proposed would replace the current approach and current systems. The ASAP reporting process and platform are online and efficient, he noted, and quickly gather critical data and information directly from the individuals involved in incidents and unsafe conditions. If such a program was used offshore, he suggested, it should be a replacement for current systems, not an add-on, so it would not create more work.

A MULTIFACETED APPROACH

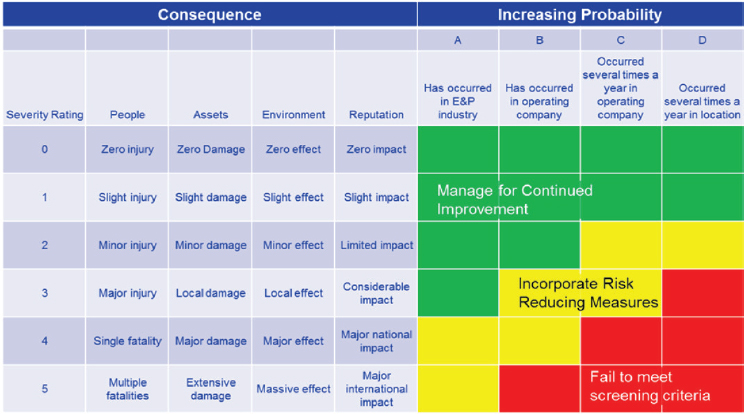

Grossweiler offered some opening comments to set the stage for a free-flowing discussing during the “fishbowl” session. He began by observing that a jet can fly 7,000 miles nonstop carrying 300 passengers. “It is amazing that there is enough energy stored in those tanks to fly 7,000 miles,” he said. “That is our industry. We create that fuel. But that is hazardous fuel. Loss of containment, an ignition, and something else bad can happen. We work in a high-risk environment. We need high-reliability organizations.” Grossweiler also emphasized the need to complement work in the areas of occupational safety and process safety with strong contributions from expertise in areas related to organizational development. He suggested considering organizational development paradigms from such thinkers as Peter Drucker and Edward Deming. He also encouraged participants to think from the perspective of the “risk matrix” shown in Figure 9-1, with attention to occupational safety generally in the “green” region, to process safety generally addressing hazards in the “yellow” region, and to the barriers to major industry incidents in the “red” region. Grossweiler also suggested that consensus on a single definition of leadership or safety culture is unlikely; rather, those companies working to continuously improve risk management frameworks and safety programs will probably have differing

SOURCE: Reese Hopkins and Karl Van Scyoc. Prepared for and presented at the Process Safety Symposium (Texas A&M) organized by the Mary Kay O’Connor Process Safety Center (unpublished). Presented by Philip Grossweiler at the workshop.

approaches. He quoted Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart’s statement, “I know it when I see it” as a paradigm for deciding whether any specific company, or organization, or industry has effective leadership and programs for managing risk.

The offshore oil industry has multiple stakeholders, McLendon pointed out in closing. As a result, all of the workshop attendees, regardless of the sectors they represent, can help improve safety in the offshore oil industry. “What will you do when you leave here today?” he asked.

This page intentionally left blank.