7

Current Systems for Worker Responses to Unsafe Conditions, Worker Interventions, and Reporting

The concept of worker empowerment implies that employees will have multiple and effective ways of reporting safety concerns and generating responses to those concerns. Three presenters at the workshop looked specifically at such systems.

A SYSTEM FOR GATHERING INDUSTRY-WIDE SAFETY DATA

Tom Knode, health, safety, and environment (HSE) director of Athlon Solutions LLC, described an initiative focused on the gathering of industry-wide safety data. He reported that in 2014, the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE) approached the Society of Petroleum Engineers (SPE) regarding a potential collaboration on the development of a framework to enhance the industry’s ability to capture and share key lessons from significant near-miss events, with the objective of identifying and mitigating potential high-consequence events. A workgroup was formed that included representatives from SPE, BSEE, the Bureau of Transportation Statistics, the Center for Offshore Safety, the Ocean Energy Safety Institute, the International Association of Oil and Gas Producers, and the American Bureau of Shipping, as well as operators and service companies, to explore the benefits of and mechanisms for collaboration. The initiative involved approximately 2 years of meetings with about 18 industry representatives who reviewed options and benchmarked conditions both within and outside the industry. According to Knode, “we looked at what the aviation industry was doing, we looked at what the maritime industry was doing, we looked at what the rail industry was doing, we looked at what the nuclear industry was doing, and we looked around the globe for what the oil and gas industry was doing.”

The result, Knode continued, was a framework for a summit that would address the opportunities and gaps identified and leverage strategic processes, both new and existing, with respect to the collection, analysis, and dissemination of data. He described as an overarching goal to encourage and facilitate continuous feedback and learning in support of ongoing safety management systems without being duplicative or creating additional burdens. “We were very sensitive to the fact that we did not want to create one more requirement to report things,” he stressed.

Knode stated that one of the biggest concerns identified in this process was the need for data privacy. Data must be collected in such a way as to protect companies that submit the data, he explained, while ensuring that the data have adequate learning value for mitigating risks and enhancing safety. For example, he elaborated, concerns had been expressed that people could access data from the government through the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) or that regulators would have direct access to the data. He cited as a way to address these concerns the Confidential Information Protection and Statistical Efficiency Act of 2002 (CIPSEA), which protects data gathered by federal statistical agencies from lawsuits and government agencies as well as FOIA requests.

Knode stressed that the intent was for the collected data to help in establishing pathways for addressing the opportunities and challenges of

industry-wide safety data management. “The industry does not need another slips, trips, and falls database,” he said. “The industry needs data that may be unique to one company [and] may be viewed as a one-off event—but wait a second. That same event has happened 10 times to 10 different companies, and nobody is connecting the dots.” He argued that such data would make it possible to identify hidden trends and would result in findings that would be immediately actionable, so that positive changes could result quickly.

In response to a question, Knode said he appreciated the tension between the regulator and the regulated. But he pointed out that BSEE approached SPE to facilitate a dialogue on this topic, which is indicative of the agency’s “willingness to get input from people who know what is going on.” He clarified that BSEE wants to oversee the industry without going through the rulemaking process.

Knode explained that the April 2016 summit led to a technical report containing recommendations to the industry, which in turn has led to a trial program (enhancing the capabilities of SafeOCS)1 to explore mechanisms for gathering and analyzing the data and disseminating findings. He added that the data will be gathered voluntarily from companies that see the advantage of using their experiences to improve safety, and industry experts subject to the above privacy requirements will work with government statistical analysts to identify what data are important and what they mean. “If we do this right,” he asserted, “we can be a model for the rest of the world.” He added that regulators around the world are interested in the report and want to see the initiative succeed “because if it does, we can collect this information not only for the Gulf of Mexico but around the world and, as an industry, get on top of trends.”

ADAPTING A SAFETY PROGRAM FROM THE AVIATION INDUSTRY

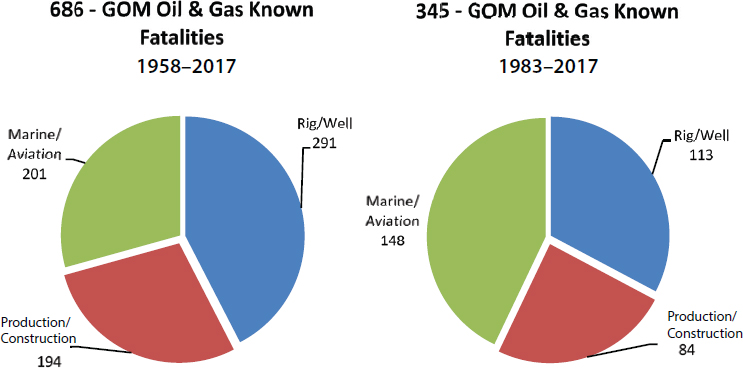

Joseph Leimkuhler, vice president, drilling, for LLOG Exploration LLC, reported that between 1958 and 2017, 686 known fatalities occurred in the oil and gas industry in the Gulf of Mexico (see Figure 7-1), 345 of which had occurred since 1983. He added that a Centers for Disease Control and

___________________

1 SafeOCS was developed in 2013 through an Interagency Agreement between BSEE and the Bureau of Transportation Statistics (BTS) to provide employees or companies a mechanism for voluntary submission of information on safety-related incidents to BTS. The scope was expanded following promulgation of the Well Control Rule in 2016 to capture regulatory-required equipment failure data. As a result of the summit, the next focus of SafeOCS was to explore a voluntary industry-wide safety data management framework. For more information about the SafeOCS Program, see https://www.safeocs.gov [May 2018].

SOURCES: Created and presented by Joseph Leimkuhler at the workshop. Adapted from data obtained from the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement Website, the Helicopter Safety Advisory Conference Website, and the National Transportation Safety Board.

Prevention study2 examining offshore worker fatality rates concluded that the rate was seven times higher than the U.S. average for all occupations. However, he noted, transport to the jobsite and non-work-related fatalities were not taken into account for other occupations, and the highest-risk exposure faced by the offshore workforce, on the basis of time exposed, is flying to the offshore facility. When those fatalities and non-work-related deaths are removed from the data for 2003 to 2010, he explained, the number of fatalities is 45 out of a total of 128, which is 2.5 times the average fatality rate for all occupations. Furthermore, he added, the number of fatalities from helicopter accidents has been declining, and there were none from 2015 to 2017.

If the Macondo fatalities are removed from the 45, Leimkuhler continued, the fatality rate drops to 1.8 times the national average. He stated that calibrating fatality rates by activity yields further insights. He noted that the numbers of people onboard per rig and man-hours per rig have risen significantly as activity has moved to deep water. But, he added, most

___________________

2 Gunter, M.M., Hill, R., O’Connor, M.B., Retzer, K.D., and Lincoln, J.M. (2013). Fatal injuries in offshore oil and gas operations—United States, 2003–2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 62(16), 301–304.

if not all of the new positions are not in high-risk areas on the rig floor and decks, and the number of those exposed positions per rig has been roughly constant. By that measure, he argued, the incident rate per number of working rigs is the best indicator of trends.

According to Leimkuhler, during the “git ’er done” era of the 1960s and 1970s, this rate was very high and was increasing over time. “I came into the industry in 1980 as a mud engineer,” he said, “and I was shocked at [what] was going on and the risks that people were taking.” But he explained that the years 1980–1981 saw a step change in offshore fatalities as a result of safety becoming part of the job. Since then, he reported, on a fatality-per-rig basis, fatalities have been flat at 1.5 deaths per 50 working rigs. With 25 to 50 rigs operating in the Gulf of Mexico over the past 5 years, he elaborated, the statistics say that one to two people will die on the rigs each year.

Leimkuhler characterized that rate as still unacceptably high, and pointed to the aviation industry as the source of the evidence for that statement. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) faces the same challenges as BSEE, he observed, in that it regulates a high-risk industry with a very high level of consequences from incidents. Thus, he argued, the FAA’s challenge to regulate, manage, investigate, and analyze incident data and promote safety is just as daunting as that of BSEE. However, he observed, the FAA and the airlines have been able to achieve zero fatalities, noting that the last U.S. commercial airline to crash with passenger fatalities was in 2009. Yet there are 8.7 million flights per year and 2.2 million passenger-miles flown per day in the United States.3

The difference, Leimkuhler asserted, is a program called the Aviation Safety Action Program (ASAP). Under this program, data collection methods and program details are agreed upon by the FAA and the airlines through a memorandum of understanding. Staff are trained in how best to use the system to ensure privacy and confidentiality. In the event of an incident, an Event Review Committee (ERC) is formed, with one member from each party (the carrier and the FAA plus an employee representative, usually a union representative), and an ASAP manager not on the ERC reviews reports, enters the data to be analyzed, and sends appropriate reports to the ERC to be either accepted or rejected. Once a report has been accepted, Leimkuhler explained, both the individual reporting the incident and the company are protected by law from FAA- or company-imposed punitive actions, including FOIA requests. Thus, he said, employees can be confident that the problem will be fixed with no concern for what happens to them. Indeed, he observed, they are likely to be more concerned about what happens to them if they do not report the incident. He added that

___________________

3 Calculated from data available at https://www.transtats.bts.gov/TRAFFIC [May 2018].

companies need not fear regulatory consequences such as civil penalties as a result of employee reporting. He noted that ASAP reports will not be accepted by the ERC if someone was drinking alcohol or taking drugs, if there was criminal activity, if there was intentional disregard for safety, if someone lied on a report, if there was delayed reporting, or if the incident was a recurrence of a similar incident with the same individual(s). If one of these six conditions applies, he said, the conventional punitive investigation approach is taken.

Leimkuhler reported that he attended an ERC meeting with a representative from the airline, a representative from the transportation safety workers union, and a representative from the FAA. “You couldn’t tell who was who” he said. “I saw unbelievable cooperation between all three, and it’s that framework, both operational and legal, that allows for quick analysis and corrective action to happen.”

Leimkuhler went on to report that BSEE is evaluating the applicability of ASAP to offshore operations. The problem to date, he said, is that BSEE does not believe it has the legal authority to grant the exceptions that exist in the airline industry. He explained that the offshore oil industry has more players relative to aviation, including rig contractors, operators, service companies, and BSEE. But he suggested that ERCs could include representatives from all these players, and a petroleum safety action plan (PSAP) could be added as a requirement to operators’ Safety and Environmental Management Systems (SEMS) through element 164 (employee participation) and element 11 (incident investigations). Moreover, he observed, the HSE bridging document between the operator and rig contractor could be adjusted, and the commercial agreements already require all service companies to comply with operators’ SEMS. Thus, he argued, BSEE could make a PSAP Program part of the SEMS performance standard.

Leimkuhler concluded with a set of specific recommendations. First, he suggested, Gulf of Mexico helicopter operators could be encouraged to work with BSEE and the FAA on an ASAP under existing laws that govern the FAA and airlines, and recent excellent performance in offshore helicopter operations need to continue. He added that a pilot program could be implemented in the Gulf of Mexico with minor if any changes to the protocols established between the FAA and the airlines. In addition, he said, separate ERCs could be formed for production/platform operations and rig/well operations. He stressed the opportunity to save three to four lives per year in U.S. outer continental shelf oil and gas operations.

During the discussion period following his presentation, Leimkuhler argued that such a program should not be voluntary. He observed that the

___________________

4 See additional SEMS Program elements at https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CFR-2013-title30-vol2/xml/CFR-2013-title30-vol2-part250-subpartS.xml [April 2018].

people who should be submitting the reports are the workers unloading the boats and handling the pipe and drill tools on the drilling floor, and they should not be worried that if they file a report they will be fired or face other punitive actions. “These people need to feel confident that they are protected if they act and report in good faith,” he insisted. “Unless you take those barriers out, we are just nibbling at the edges.”

Also arising in the discussion session was the point that all large carriers and an increasing number of small carriers participate in ASAP. It is more difficult for small carriers with just a few pilots to be part of the program, but the difficulties can be overcome. Also, all airlines accrue benefits from participating in the program because then they can access the data to discover weaknesses. Furthermore, the data are used to train pilots, enabling them to remain up to date on the latest issues uncovered by the system.

“It feels like we just keep nibbling at the edges” in the offshore oil industry, Leimkuhler said, adding, “I’m tired of nibbling at the edges.” He reiterated that the airline industry provides a template that could be used offshore. “If we had that kind of program where every rig was forced by law to operate under the same system,” he argued, “I wouldn’t have to worry about reporting protocol and to a large degree about safety culture as my operations pick up and release drilling rigs. I wouldn’t have to worry about investigation protocol and how that varies from rig to rig; it would all be fixed—it would be consistent across the Gulf and across the industry. And if we were to do that, I honestly feel every employee would see and feel the same thing…if I report the incident/situation it will be addressed…and I do not have to worry about what happens to me.” He ended by saying, “That’s what I think we really need to see for empowerment—a framework that we all operate within that’s mandated by law.”

ENHANCING WORKER EMPOWERMENT IN REFINERIES IN CALIFORNIA

Contra Costa County, which is across the bay from San Francisco and is home to about 1.4 million people, houses four oil refineries and a number of chemical facilities, noted Randy Sawyer, the county’s chief environmental health and hazardous materials officer. In the 1980s and 1990s, he observed, these facilities experienced accidents on an annual basis, some of which caused loss of life, serious injuries, and chemical exposures to large populations. In response, he explained, the county instituted an industrial safety program that expanded on the federal risk management program. It also arranged for audits of the facilities to ensure their compliance with regulations.

Yet, Sawyer continued, accidents continued to occur, including a chemical release that resulted in more than 15,000 people seeking medical atten-

tion. The governor then convened a working group to investigate how to prevent such accidents. Sawyer explained that the group issued a number of recommendations, one of which was to examine best practices in industrial safety occurring at the county level and incorporate them at the state level. The result was the California Accidental Release Prevention (CalARP) Program.5 According to Sawyer, the program created requirements at the state level, but they are implemented by local jurisdictions by what are called unified program agencies. Depending on definitions, he added, California has about 15 refineries that are covered under the program.

Sawyer identified employee participation as an important aspect of the program. He explained that the regulations state that “in consultation with employees and employee representatives, the owner or operator shall develop, implement and maintain a written plan to effectively provide for employee participation in Accidental Release Prevention elements.” He reported that these plans include provisions that provide for the following:

- Effective participation by affected operating and maintenance employees and employee representatives, throughout all phases, in performing process hazard analyses, damage mechanism reviews, hierarchy of control analyses, management of change, management of organizational changes, process safety culture assessments, incident investigations, safeguard protection analyses, and pre-startup safety reviews.

- Effective participation by affected operating and maintenance employees and employee representatives, throughout all phases of the development, training, implementation, and maintenance of the Accidental Release Prevention elements required by this Article.

- Access by employees and employee representatives to all documents or information developed or collected by the owner or operator pursuant to this Article, including information that might be subject to protection as a trade secret.

Sawyer added that the program specifies that an authorized collective bargaining agent can select employees to participate in the development and implementation planning of the program. Where employees are not represented by an authorized collective bargaining agent, the owner or operator needs to establish effective procedures, in consultation with employees, for the selection of employee representatives.

According to Sawyer, the program also requires that effective pro-

___________________

5 More information about the California Accidental Release Prevention Program is available at http://www.caloes.ca.gov/cal-oes-divisions/fire-rescue/hazardous-materials/california-accidental-release-prevention [May 2018].

cedures be instituted to ensure the right of all employees, including the employees of contractors, to report hazards anonymously. Owners or operators need to respond in writing within 30 calendar days to written hazard reports submitted by employees, employee representatives, contractors, employees of contractors, and contractor employee representatives.

An emphasis within the program, Sawyer continued, is the existence of effective stop-work procedures. All employees, he elaborated, need to be able to refuse to perform a task that could reasonably result in death or serious physical harm, and to recommend to the operator in charge of a unit that an operation or process be partially or completely shut down based on a process safety hazard. He added that a qualified operator in charge of a unit needs to have the authority to shut down an operation or process partially or completely based on such a hazard. Shutting down a process is a “big thing,” he acknowledged, but the program “gives employees more ability to take action.”

Finally, the moderator of the session, Christiane Spitzmueller, briefly mentioned the work done by the Interstate Natural Gas Association of America to collect safety culture data using the same questions and same survey instruments across the industry. She explained that the association has developed a framework for sharing the data with careful privacy protections so that all companies can compare themselves with the industry averages and industry best practices.

This page intentionally left blank.