3

Community Resilience

SETTING THE STAGE

The moderator, Arrietta Chakos of Urban Resilience Strategies, opened the community workshop with a conversation among Roy Wright, deputy associate administrator for mitigation at the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA); Andrew R. Brenner, senior manager for global communications at the 100 Resilient Cities program pioneered by the Rockefeller Foundation; and Lauren Alexander Augustine, director of the Program on Risk, Resilience, and Extreme Events at the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies) about how resilience efforts are making a difference in communities and ways to scale efforts regionally and nationally.

Chakos asked Wright to discuss how FEMA works with local governments and what local and regional governments can learn from federal policies. Wright emphasized that the federal government can help communities through national programs but will not be able to change the profile of a community related to its risks. Instead, FEMA provides building blocks of resilience to support local officials in making choices for their community, exemplified through the National Flood Insurance Program and various grants and other programs. He acknowledged that building resilience can be fundamentally different, depending on the community, and that prioritizing and paying for resilience can be very difficult. For example, many communities that experience a disaster may lose part of the population of

their community; this can lead to a reduction in their tax base, which can affect a community’s ability to fully bounce back. Another challenge is that local elected officials have many conflicting issues to address with resilience being just one business-line of many in a mayor’s budget.

Chakos asked Brenner to talk about common themes that have emerged from the 100 Resilient Cities work and discuss how the cities are planning to pivot from developing resilient strategies to implementation. Brenner stated that each city develops a city resilience strategy and that these strategies have helped the cities identify new ways to assess risk, think differently about implementation, and identify new partners to bring to the table from the private, public, and other sectors. So far, 12 Rockefeller cities have released a resilience strategy. Brenner stated that many cities identify similar needs for addressing shocks and stresses. Not surprisingly, more than 80 percent of cities in the 100 Resilient Cities program identified a water issue—either too much or too little—as their top shock or stress. The program is leveraging the expertise of cities wherever possible, bringing them together to problem solve specific issues and common challenges.

Chakos asked Augustine to talk about the role of science and engineering in the work of resilience action. Augustine stated that disasters and resilience are not single sector issues but involve everybody. The National Academies exercises its convening power to bring diverse decision makers and stakeholders to the table. She emphasized the role of science and data, and the need for its interpretation and translation to provide accessible and meaningful information to underpin community decision making.

The three panelists discussed the trajectory of resilience over the next 5 to 10 years. Brenner sees cities learning from one another’s efforts, for instance by appointing a chief resilience officer in the government. This person constitutes a focal point for resilience, helps to bring together many business-lines in the budget, and identifies outside resources from the community and private sector to integrate into the process. Brenner sees new approaches being brought forth simply by virtue of the chief resilience officer being at the table. Wright noted the momentum of the resilience movement, but also commented that resilience stills needs more direct integration into local decision making and investments by the private and public sectors. Success means moving resilience beyond a niche environment to something that is pervasive across multiple sectors, organizations, and disciplines. Augustine referred to a question posed the previous day about how to take credit for something when, if done right, nobody notices. She noted the importance of the 100 Resilient Cities program in promoting and support-

ing a larger conversation on resilience; the question now is how to take these big programs and pilot efforts and operationalize them so that they are part of everyday thinking.

Finally, an audience member asked how to replicate and transfer resilience lessons. Brenner replied that it is hard for cities to grapple with the complex challenges of the 21st century on their own. Outside expertise helps cities to think through their challenges and potentially replicate ways that other communities are approaching risk and working toward solutions. Brenner concluded that open and honest conversations about risk are important and sometimes it takes a shock to have happened for resilient thinking to become fully embedded in a community.

ENGAGING WITH DIVERSE POPULATIONS

Lori Peek, professor, Department of Sociology and director, Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder, explained that the planning committee’s choice to use the term diversity rather than vulnerability during this discussion was deliberate. It was meant to avoid a common consequence of discussion around vulnerability, which often results in developing lists of the types of people who are most disadvantaged—those with the least power, least resources, and least voice within communities. The planning committee favored the lack of directionality inherent in “diversity” and the broader range of what it can include in terms of people, places, or perspectives. Peek also acknowledged, however, that the lack of directionality in “diversity” has the potential for participants to lose sight of the inequalities that exist in people’s differential opportunities and that are embedded in histories, structures, and political systems of communities and the nation as a whole.

Peek introduced the panelists and asked them to briefly describe some of their core projects. June Kailes, disability policy consultant and the associate director and adjunct associate professor at Harris Family Center for Disability and Health Policy at Western University of Health Science, began the discussion. The primary focus of Kailes’s work is to ensure delivery of services in an equal and effective way to people with disabilities and with access and functional needs. She works on building disability competencies, practice competencies, and actionable competencies in health care and emergency management; developing courses for FEMA; and assisting states, cities, and counties in developing inclusive emergency plans. Kailes explained that the people for whom she advocates constitute 50 percent of

the U.S. population and include those with vision and hearing loss; physical disabilities; mental health disabilities; developmental, intellectual, and other cognitive disabilities; behavior health issues; learning, understanding, remembering, reading, and speaking limitations; mobility limitations; serious allergies and chemical sensitivities; limited English language abilities; and those who are transportation dependent.

Nick Kushner, project manager in the Office of the Deputy Mayor for Health and Human Services in the District of Columbia government, introduced his work with the Age-Friendly DC program,1 which is part of the AARP Network of Age-Friendly Communities through the World Health Organization Global Network of Age-Friendly Cities and Communities. This program brings an inter-generational focus to city planning by putting the views of older residents at the forefront. In addition, as part of its mission to build an inclusive city, the District of Columbia is revising its comprehensive plan to include resilience and incorporating a range of issues from the age-friendly approach such as access to transportation, housing, community health services, long-term care, social participation, respect, and inclusion.

Robin Pfohman, program manager for the Community Resilience + Equity program in the Department of Public Health in Seattle and King County, Washington, discussed her work with a King County community resilience framework focused on health, equity, and climate change. She acknowledged that an invisible line exists in the Seattle region in which people struggling with certain disparities—in terms of life expectancy, tobacco use, mental distress, negative childhood experiences, diabetes, and preventable hospitalizations—have to live farther and farther from the city of Seattle. This pattern necessitates a countywide perspective to ensure conversations are not Seattle-centric and that communities that need assistance remain part of the discussions.

Peek asked the panelists to share examples of how to integrate the needs of diverse populations into a formal plan, process, or vulnerability reduction initiative. Kushner pointed to the development of Age-Friendly DC. At the start, they engaged hundreds of George Washington University students to spend time with District of Columbia residents and listen to their concerns. Across the city, students walked with long-time residents—people using wheelchairs or canes and young families using strollers—as they told stories about the neighborhood, discussed their access to places such as pharmacies

___________________

and sources of healthy foods, and talked about problems that needed attention such as roads in disrepair, unsafe sidewalks, and unsafe traffic intersections. The data were used to advocate for funding to address those needs.

Pfohman described an effort in Seattle to test and disseminate emergency messages to the region’s Somali community; ultimately, it resulted in the formation of the Somali Health Board. The city’s primary connection with the community revolved around health issues. Because a past communication effort around H1N1 had left impaired relationships when it did not take into account cultural sensitivities, for this next effort the city partnered with a Somali organization and worked with a local Somali health professional to conduct focus groups around vaccines and other health issues important to the community. This helped build relationships and resulted in the project evolving from a focus on emergency messaging to health and ultimately the establishment of the Somali Health Board. The city had considered the Somali population as vulnerable. However, by better understanding the assets in the community and helping to build capacity, the Somali community started its own nonprofit organization, successfully applied for grants, and took the lead on the health and well-being of their community.

Kailes discussed two success stories involving the American Red Cross that demonstrate recent progress in the integration of communities with disabilities into emergency planning and response. In one instance, several shelters need to be opened very quickly following a large emergency. When Red Cross staffers inspected the designated facilities, they found the locations were not accessible and refused to open the shelters. The conflict rose to the state attorney general’s office, which recognized that the designated facilities were not suitable and supported the Red Cross in opening appropriate shelters. In a second example, Kailes described advocacy efforts focused on the need to accommodate people with disabilities in shelters designed for the general population, by providing a few specific alterations. Kailes described how disability advocates asked the Red Cross to observe the Americans with Disabilities Act, to update their policies and procedures to engage in community partnerships with the disability community, and to provide a management position for a disability inclusion coordinator. She reported that in 2015 the process had begun, with the development of stronger partnerships and problem solving for more inclusive sheltering and response services.

Each panelist provided thoughts on how communities, states, or the federal government could approach and integrate diverse populations

across the disaster lifecycle. Pfohman noted that resilience could be a hard sell because the focus is on an acute distinct event, while the reality is that many residents have disasters every day and preparing for emergencies is a luxury for many people. She believes that opportunities around resilience are broader and urged approaching resilience not with the assumption of deficit but as an opportunity to address existing inequities, linking disaster preparedness to daily life.

Kailes advised leaders to “embrace the fact that an emergency dogma is perishable and should have a short expiration date.” She advocated infusing practices based on new, evolving information, economics, laws, technology, values, products, and services. The goal is not lessons heard about, observed, or even documented, but lessons repeatedly applied until we can eventually claim them as learned. Kailes urged decision makers not to consider people with disabilities a small population to address in the future, reiterating that this group constitutes 50 percent of the population. Jurisdictions must plan for known needs by providing inclusive transportation, addressing health and safety issues, and contributing to the maintenance of residents’ health and independence.

Kushner discussed the importance of connecting with diverse organizations and recognized the natural fit between health policies and resilience policies. He described the need to meet people where they are and address the increasing isolation of residents, for example, his organization works with home-delivered meal services as a way to get messages to residents. He cited a program in Utah through which a person can sign up for a buddy system, allowing the person delivering meals to contact a client’s friend or neighbor if the client is unreachable.

Peek asked each panelist how they convince decision makers to integrate the needs of diverse groups into planning and practice, and what quantitative or qualitative metrics would be most effective in measuring success. Kailes advised against registries or lists of people who need to be moved in the event of a crisis or extreme event as a model intervention, pointing out that there is little evidence that registries are successful. For example, where a person lives does not say anything about where they are at the time of a crisis; this can result in wasted time for first responders. Regarding metrics, she suggested an evolving checklist for integrating people with disabilities, access, and functional needs into preparedness, response, and recovery plans, and noted the need to include these procedures in funding requirements.

Regarding emergency services, Kailes recommended the use of the U.S.

Department of Justice compliance accessibility checklist and emphasized the need to make sure that community data are available and consulted before emergency response sites are opened. Emergency communication with residents should be available in usable, understandable formats and accessible to a wide range of people. Lastly, she urged the use of just-in-time training and checklists, given high levels of staff turnover and the simple fact that there is too much information to be stored in memory, especially during the stress of an emergency.

Kushner asserted, “We’re not resilient if we’re not inclusive, if we’re not looking at equity in how we’re planning and doing outreach, and in who is at the table.” He described community organizations called “villages”—networks of neighbors that arise organically and provide services like transportation or plumbing help—that function as a long-term support system for people to continue to age in their community. He noted that while these organizations are now primarily in upper-income neighborhoods, the District of Columbia is trying to foster connections in other neighborhoods through faith-based and community-based organizations. Regarding metrics, Kushner said that often the government has only partial data on different communities and suggested a need to work with other community organizations to tap into existing efforts to collect additional information, through annual health surveys, for example. He revisited his work with the World Health Organization on the age-friendly program, which collected data on multiple age-related mobility factors such as sidewalk connectivity, rates of elder abuse, and the number of certified trainers in the public. Pfohman described her efforts to shift the paradigm in King County by working across different communities to bring together initiatives around health, climate change, and emergency preparedness. Metrics can be helpful in defining this shift.

HEALTHY COMMUNITIES

Natalie Grant, program analyst, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, moderated a discussion about what it means to be a “healthy community.” She opened the conversation by noting that the phrase “healthy communities” runs a broad gambit from public health to health care services and beyond, and asked the presenters to discuss not just the components of a healthy community, but also the challenges and how to overcome them. Grant called attention to a 2015 report Healthy, Resilient, and Sustainable

Communities After Disasters,2 which includes case studies and best practices, addresses communication with different audiences, and discusses the incorporation of health into the pre- and post-disaster environment.

Jeanne Herb, director of the Environmental Analysis and Communications Group at the Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy at Rutgers University and co-facilitator of the public–private partnership New Jersey Climate Adaptation Alliance, talked about health impact assessments (HIA), a tool designed to determine the health impacts for a given disaster and identify ways to integrate health into non-health decision making. Herb referred attendees to the 2011 report Improving Health in the United States: The Role of Health Impact Assessment.3 She described how HIAs bring together data from the public health literature and local knowledge of residents to make predictions about the health impacts of a given decision point.

After Superstorm Sandy, the New Jersey Climate Adaptation Alliance

___________________

2 Institute of Medicine. 2015. Healthy, Resilient, and Sustainable Communities After Disasters: Strategies, Opportunities, and Planning for Recovery. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/18996.

3 National Research Council. 2011. Improving Health in the United States: The Role of Health Impact Assessment. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/13229.

performed two place-based HIAs and formulated a set of general recommendations on the value of integrating HIAs into resilience planning.4 The two locations chosen were Little Egg Harbor and Hoboken, New Jersey, both of which suffered damage from Superstorm Sandy and experience regular flooding. Neither included health analysis in their post-disaster planning process. The question posed in the HIA for Little Egg Harbor was, “What if 500 properties were bought out and returned to a natural state for purposes of flood mitigation?” Hoboken asked, “What would be the impact to the city if it were to adopt a comprehensive green infrastructure plan to address inundation (not event-related) flooding?” For Little Egg Harbor, the health factors studied included mental health impacts, likelihood of injury, and impacts resulting from evacuations, power outages, and disruptions in infrastructure. Community concerns included the impacts of flooding on household finances, municipal finances, social cohesion, and open spaces. For Hoboken, the community’s concerns included sewer overflow events, open spaces, air quality and the urban heat island effect, changes in economic conditions, exposure to hazardous substances, and noise pollution.

Herb discussed the HIA’s success in bringing people to the table to discuss the topic of health; combining science, data, and evidence with the local knowledge of residents; and contributing to a more democratic, community-based process. She also described some of the limitations with the process and made two recommendations for future practitioners. First, it is important to be aware of inherent disaster-related decision points faced by communities and try to seize on opportunities, both before and after disaster. For example, in the wake of a flood, a city has a unique opportunity to buy up damaged properties in flood-prone areas, especially before homeowners initiate repairs, after which they are far less likely to want to sell. Second, HIAs typically answer a single decision point rather than provide options for alternative analysis; it could be beneficial to modify HIAs so that they can inform alternatives.

Nick Macchione, agency director of health and human services for San Diego County, California, discussed the county’s 10-year initiative known as Live Well San Diego,5 which sought to improve the health and wellness of the city. Live Well San Diego addresses both emotional and physical

___________________

4 Carnegie, Jon, and Ryan A.G. Whytlaw. 2016. “City of Hoboken, New Jersey Proposed Stormwater Management Plan Health Impact Assessment (HIA): Final Report.” http://phci.rutgers.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Hoboken-Stormwater-HIA_FinalReport_v9-19-16.pdf.

wellness as well as disaster preparedness, life expectancy, quality of life, safe neighborhoods, housing, jobs, food security, and bringing the natural and built environment together. Macchione indicated that life expectancy was a key metric of the program, which started with the study of neighborhoods where residents had lower life expectancy. Studies of trauma found that adverse childhood experiences lead to a loss of 5 to 10 years of life expectancy and identified the roughly 5,000 children in foster care as those least likely to recover from trauma. As a result, keeping kids out of foster care became a chief goal. Live Well San Diego posed the question, “How do we build the resilience of families in crisis, particularly those families that are disproportionally in crisis?”

Considering parents as partners not patients, they took a strength-based approach to look at the assets of nuclear families and extended families and asked if their system was culturally appropriate and truly enabling families to build resilience. Services were targeted toward keeping families together. Macchione highlighted the success they experienced by engaging grandparents, which he referred to as a “natural resource” and “turbo-boosts of resilience.” Rather than sending families through the court system, which would ultimately require the county to provide certain services, the county opted to provide those services upfront. The program took an unprecedented approach working with nontraditional partners that included, for example, businesses, employers, and transportation and housing organizations. They supported minority-owned businesses, and brought jobs into communities allowing residents to live and work near home; this helped to keep their social networks intact and built up their family’s resilience. Macchione shared several lessons learned from the program:

- Wellness is not just a checklist, rather an organic process.

- Meet families where they are already.

- Build the capacity of people.

- Combine health and safety, such as in creating safe corridors for walking to school.

- Government cannot do it alone.

- Work across disciplines and agencies (“harmonize to humanize”).

- Use the power of stories.

The moderator asked how the panelists responded to city or county collaborators who felt adding health considerations was overloading already full plates. Herb responded that using HIAs to guide resilience work makes

health “not one more thing, but the thing.” Macchione said the approach taken by Live Well San Diego, which took place over the course of 6 years, made clear the interconnectedness of a range of critical issues, not just health. He indicated that building resilience in communities was not a quick fix—it has a long time horizon—and that patience and sustainability of efforts are both necessary for success.

An audience member noted that a community could not be resilient unless individuals see themselves as resilient and asked how the speakers worked with individuals. Macchione pointed out that many families in the lower socioeconomic spectrum who have large social support networks are thriving. Live Well San Diego developed its Resident Leader Academy to encourage neighbors to talk to each other rather than with the government and generally be active citizens. Herb agreed that some vulnerable communities are the most resilient. However, she noted that the community can often be blind to its own weaknesses, and can require tools and assessments to help identify specific needs. Her group is developing tools for communicating social determinants of resilience to address this gap.

In conclusion, the moderator noted that both speakers focused on the intersection of health and the environment, and stressed the importance of working across disciplines and looking for dual-use functions. Both speakers agreed that the strength of the individual was important and that some data, such as demographics, might not be representative of resilience; for example, a family with minimal financial resources might be extremely resilient because they are socially connected. As Macchione phrased it, “Vulnerable does not necessarily equal not resilient.” Lastly, Grant reminded everyone that building healthy communities takes time and there are critical decision points along the way.

BUILDING PARTNERSHIPS AND COALITIONS

Jane Cage of Joplin, Missouri, a volunteer with the Citizen Listening Effort and Long-Term Recovery Plan after the city’s tornado disaster in 2011, cited the African proverb, “If you want to go fast, go alone, but if you want to go far, go together,” to introduce the discussion on how communities can build stronger partnerships and networks to address their resilience challenges. Cage asked the speakers to discuss how partnerships and coalitions can build resilience in a better and more productive way.

Miriam Chion, planning and research director for the Association of Bay Area Governments (ABAG) in San Francisco, California, described her

work on Plan B, a California state requirement to reduce greenhouse gases by linking land use and transportation.6 The plan’s focus areas are (1) priority conservation areas, formed to retain natural resources, agricultural land, or open spaces, and (2) priority development areas, new development aimed at “complete communities,” where residents have access to transit, schools, jobs, and services. She emphasized that both must be locally defined since they can vary dramatically in scale.

The Bay Area faces a variety of natural hazards, from drought and sea level rise to seismic activity and socioeconomic challenges. ABAG convenes activities around relevant issues in the region, for example, strategic water use and conservation and earthquake risk. Chion described an area of focus on the East Bay corridor, a span of industrial land that provides a transportation corridor for the movement of goods, but also sits on a major seismic fault line. The area’s residents compose disadvantaged and homeless populations alongside an influx of upper middle class residents seeking relief from the high price of housing in San Francisco. Through work in this area and other key locations, ABAG has put forth three main recommendations

___________________

6 California Climate Change Adaptation (http://www.climatechange.ca.gov/adaptation).

for local policy makers: (1) grounding the regional process in the diversity of the local communities, (2) identifying the specific knowledge required to integrate resilience, equity, and sustainability into one vision, and (3) aligning resources and decision making.

Dan Burger, chair of the Charleston Resilience Network and director of the Coastal Services Division for the South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control (DHEC), described DHEC’s efforts to understand coastal hazards and vulnerabilities—hurricanes, sea level rise, storm surge—and the impact on socioeconomic continuity, natural resources, and the built environment. By making coastal data more accessible and digestible, DHEC provides a path for local communities to integrate information into their plans. Burger’s team aims to provide opportunities for municipalities and counties to understand their vulnerabilities, identify opportunities to enhance resilience, and create financial benefits for residents.

In 2014, Charleston participated in a tabletop exercise sponsored by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) Office of Infrastructure Protection. DHS convened a range of stakeholders in Charleston including resource managers, emergency managers, and academics with the goal of exploring: (1) participants’ understanding of climate-related hazards and the community’s vulnerability to these hazards, on both socioeconomic and infrastructure levels, and (2) whether organizational plans encompassed chronic disruption or were mainly a response to major episodic disasters. DHS found that while individual personal relationships were strong, participants’ understanding of the interdependencies between infrastructure and organizations was lacking. They also found that hazard and vulnerability data and analysis were outdated and varied greatly by organization. While the participants were concerned about similar issues, there was a need to align visions and resources to more effectively tackle challenges. In response to this identified need, a team of volunteers formed the Charleston Resilience Network (CRN)7 to continue the conversation and expand on the insights learned from the tabletop exercise. The CRN represents a regional collaboration of the Charleston area’s public, private, and nonprofit organizations; the group seeks to enhance the overall resilience of the community through their partnership.

Cage asked the speakers to consider some of the benefits and challenges of balancing between an informal network and a formal structure. Drawing from experience with the CRN, Burger acknowledged a tension between

___________________

keeping the organization open and egalitarian while maintaining a formal enough structure to allow for effective decision-making and strategic direction. He noted that grant funding could prompt the clarification of the highest-priority needs and the identification of organizations in the best position to collaborate in addressing those needs. Chion expressed challenges of sustained and meaningful engagement with elected officials and instability in funding, but also pointed to informal structures and networks as providing opportunities to bring in organizations that are not yet part of the resilience conversation.

Cage acknowledged that it could be difficult to balance a full-time position with voluntary partnership building, often the foundation of informal networks. Burger noted that while participation in the CRN is not a formal item of his job description, his activities in the group align well with his organization’s mission. In other words, Burger’s role in the CRN actually strengthens and supports his full-time position at DHEC. These types of voluntary networks are an ideal way for communities to capitalize on scarce resources.

Cage asked the group to consider how to lead with only influence and social capital. Both Chion and Burger noted the importance of social or political recognition for their respective groups. Specifically, ABAG has benefited from recognition through the 100 Resilient Cities program and the CRN was identified as a key organization in the city of Charleston’s Sea Level Rise Strategy. Several participants noted the importance of consensus building in the community, particularly among voters who may be pivotal in passing an ordinance or securing funding. Given the time commitment and complexities associated with consensus building, it is tempting to find shortcuts, but participants emphasized the deep value in the process itself. The process actually starts with education and awareness building; the value lies in connecting with people where they are and communicating scientific concepts and information in a way that is meaningful to them.

Participants noted that a disaster, while potentially devastating, could create an opportunity to build consensus and political support. However, Chion pointed out that it is also possible to generate interest and support even without a specific disaster event. For California, the threat of an earthquake is ever-present and well integrated into daily life. Chion noted that ABAG has been successful by focusing on past disasters and commemoration events as tools to build awareness and engagement, framing their work around broader themes such as equity and sustainability, and by building on current efforts with existing momentum.

MEASURING RESILIENCE

The moderator, Joshua Barnes, director of preparedness policy at the National Security Council of the White House, opened the session with a question, “How do we know when we’re resilient?” Barnes suggested that current approaches of determining a community’s resilience using indices and scores often contain flaws; for example, using demographic or U.S. Census data to measure resilience can be difficult to link to specific outcomes. Experts also tend to weight the measures according to their judgment. However, weighting one variable higher than another may not take into account the importance of the different variables to that community.

Barnes stated that measuring resilience must be locally driven, but there also must be some degree of consistency across communities. How do you determine the best ways to measure resilience and identify whether or not you have achieved resilience? He indicated that one way is to think about co-benefits. In other words, how can a community use existing resources (e.g., state or federal funds) to increase resilience in other areas? Moreover, how can a community measure resilience to meet the needs of different “customers”?

Barnes noted three federal initiatives focused on resilience metrics: the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Climate Resilience Toolkit;8 the recently released inter-agency concept paper, Draft Interagency Concept for Community Resilience Indicators and National-Level Measure;9 and FEMA’s preparedness grants, which require that grantees demonstrate how their investments are building or sustaining a core capability. In introducing the goals for this panel, he asked, “How can we find metrics that describe efforts in a very relevant way, so that we can show that communities have become resilient in the ways that matter to them?”

Andrea Larson, business process and data analyst for the city of Minneapolis, Minnesota, described the city’s Community Indicator Project (CIP),10 a program designed to hear from residents about whether or not they think the city is reaching its five broad goals: (1) living well, (2) one Minneapolis (elimination of disparities so all residents can participate and prosper), (3) a hub of economic activity and innovation, (4) great places, and (5) a city that works. This program originated in a data tracking and transparency program that assessed the activity and outputs of individual

___________________

8 See https://toolkit.climate.gov.

9 See https://www.fema.gov/media-library/assets/documents/117607.

departments in the city. While the tracking took place at the individual department level, strategic planning and goal setting took place at an enterprise level; thus, the city did not know if it was making progress as a city on its priorities. Following a leadership change in 2014, the program evolved into the CIP with the goal of measuring the impact of the city’s work on the community. The CIP now reports on 30 community indicators and Larson’s unit combines these into groups of one to three indicators to create analytical and insight-driven reports; this culminates in a roundtable discussion that brings together city staff and elected officials, other government agency representatives, and subject-matter experts from the community.

Larson talked about how to gain traction within an organization, how to use indicators in a meaningful way to establish a baseline, and how to assess progress on priorities. In developing the CIP, it was important that the city knew what success looked like from the community’s perspective; therefore, they reached out to various groups and asked people to describe success for each of the city’s five broad goals. The city gathered input using a crowdsourcing tool and distilled the input from 1,500 people into 200 themes. From this input, the city put together a list of all possible indicators (i.e., “universe of indicators”). They honed this universe into a “world of indicators” of about 100 and asked city leadership and staff, “Of the indicators prioritized by the community, which ones best reflect our work and our goals and best lets us know whether we’re making progress?” The result was the adoption of 30 indicators, about six per goal.

These indicators provide the basis of the city’s report, City Goal Results Minneapolis,11 which discusses the city’s role and identifies community work around each theme/indicator. The indicators cover a range of topics (e.g., number of residents below the poverty level, third-grade reading proficiencies, and water body impairments in the land of 10,000 lakes). Positive outcomes from this work include implementation of ideas that emerged from the roundtable discussions, silos being broken down as different city departments were required to work together, and incorporation of data in the city’s climate change vulnerability assessment and comprehensive planning. Challenges included limiting the number of community indicators and gaining buy-in from city departments concerned that their work would be reflected in only one or two indicators or that they would be held accountable for negative changes beyond their control. Finally, it was a cultural shift for the organization to think analytically about measures and

___________________

11 See http://www.minneapolismn.gov/coordinator/strategicplanning/citygoalresults.

data. Making observations had to give way to interpreting what the data point meant and what the city could do about it. Larson’s goal is to make the data available online and communicate the results visually to empower community members to use the data to draw their own conclusions. A key lesson learned is that organizations should first decide on the purpose of the indicators before they decide on which ones to use.

Molly O’Donnell is a resiliency planner and project manager for the Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR) infrastructure program for the Boulder County Collaborative (the Collaborative). The Collaborative is a group of cities and towns within Boulder County that came together to prioritize projects regionally for CDBG-DR funding. The Department of Housing and Urban Development required that all CDBG-DR infrastructure projects be measured against a resilience performance standard.

O’Donnell described the Collaborative’s process of creating the resilience performance standard. A major component was to establish time-to-recovery goals using the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Community Resilience Planning Guide for Buildings and Infrastructure Systems.12 One challenge was transitioning from a flood hazard mindset (the city had recently had a flood) to an all hazards mindset, which was accomplished by pivoting from flood-specific capacity and numerical measures to thinking in terms of the phases of recovery—minimal, functional, and operational. Mini workshops identified community specific time-to-recovery goals.

To arrive at resilience criteria for resilience design standards that would not conflict with existing criteria used by other organizations and governments, the group borrowed from the Colorado Resiliency Framework,13 from resilience characteristics that had emerged out of BoCo Strong,14 and from criteria coming out of research at NIST and elsewhere. Their resilience design standard uses a one-tier threshold to measure success: either the threshold is met or not. O’Donnell explained that if an infrastructure project meets the threshold, it contributes toward long-term time-to-recovery goals. The more projects that incorporate these aspects, the more resilient Boulder County will become in the face of the next disaster.

___________________

12 See https://www.nist.gov/topics/community-resilience/community-resilience-planning-guide.

13 See https://docs.google.com/a/state.co.us/viewer?a=v&pid=sites&srcid=c3RhdGUuY28udXN8Y29sb3JhZG91bml0ZWR8Z3g6MmRmMjlmMjMwOTBlMjNkYw.

In response to a question from Barnes about how to keep the process “fresh” for community members, Larson referred to the election cycle, as new leaders arrive with new priorities. In addition, she noted that the process itself is revealing what indicators the community is most interested in and which are most valuable. The city of Minneapolis is learning which indicators need to be reported and which show up naturally in many different conversations. O’Donnell stated that Boulder County communities would be able to choose whether to apply the process to additional new and current efforts.

Larson was asked if the city of Minneapolis’ indicators project helps with regional integration or building resilience in the broader region. She replied that Minneapolis is the center of a seven county metro region. Because the metrics themselves are at a high level, it is forcing the city to have a regional conversation, to think about how the city impacts the region and how the region impacts the city. They are currently talking to St. Paul about developing a similar project.

An audience member asked how the work is communicated more broadly. Larson replied that her team creates in-depth reports that tell a story about each indicator, not just simply report the numbers. They focus on communicating what factors determine outcomes on that indicator, how the city’s work contributes to the indicator, and the outcomes of those contributions. In addition, each department uses the reports for its own decision-making. The goal is to provide all the data online, use visuals to represent the results, and allow users to decide what they want to look at and do their own analysis.

Barnes closed with several themes that arose from this session. Resilience metrics should be community-driven and executed at a rate that allows the community to see progress. He also noted that it is beneficial for metrics to provide a common objective and accountability for multiple organizations, offices, or communities and that it is important to recognize that the people who produce the data are not necessarily the ones who influence the data. Lastly, he concluded, the indicators need to tell a story that is meaningful for the community.

CLIMATE ADAPTATION AND RESILIENCE

Eduardo Martinez, president of the UPS Foundation and co-chair of the Resilient America Roundtable, introduced the afternoon sessions by emphasizing the community aspect of resilience. UPS believes that support-

ing stronger, safer, and more resilient communities gives rise to an inspired workforce and a more prosperous business. He pointed to the recent United Nations World Humanitarian Summit, which emphasized preparedness and inclusivity and brought together the private sector, government, and civil society to solve problems. Martinez stated that resilient communities cannot be built by continuing to work in siloes, noting that this has also been a theme of the Resilient America program. “Not only do we want science, not only do we want to bring a tried and true approach to building resilience, but we want to create a community hub.” Martinez concluded by saying that resilience does not result in an end point but requires an ongoing, sustained approach. Everybody needs to work together toward that common goal.

The moderator, William Solecki, professor of geography at Hunter College of the City University of New York, stated that decision makers and practitioners increasingly recognize that they cannot look solely to the past climate record as they formulate policies and plans for the future. He raised the question of how to develop a public policy context that responds to the shifting environmental baseline caused by climate change. The challenge is for engineering and the construction of large infrastructure, but also pertains to how communities are constructed and how individuals connect. Looking longer-term, the need is to better understand what climate change might look like in 2050 or 2100 and how things like sea level rise or increased frequency of extreme heat waves will impact how we build cities and live our lives.

Turning to the panelists, Solecki asked them to discuss a key challenge in their work. Jennifer Molloy, of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Water Permits Division, administers many aspects of the Clean Water Act and the Safe Drinking Water Act and described her work on water quality and water quantity. Her particular focus is the National Discharge Elimination System Program, where she works with communities on wastewater and storm water programs. The biggest challenges are competing priorities for time and money. Communities are dealing with the crisis of the moment and think of water issues as something they can leave on the back burner.

Kathy McLeod, managing director of climate risk and investment at The Nature Conservancy, described her organization’s work exploring and advocating for the role that natural systems play in reducing risk to communities. A major challenge she sees is the difficulty of balancing the short term and the long term. She noted that it is critical that communities shift from

response to investment for the bigger payoff. However, McLeod admits that defining and measuring that bigger payoff is difficult. Another challenge is that communities may lack awareness of the risk they face and the role that nature can play in reducing that risk. While New York has made big investments in natural systems (e.g., to reduce wave height and energy and improve erosion control) many communities are not taking those steps.

Erika Lindsey, senior policy advisor in the New York City Mayor’s Office of Recovery and Resiliency, described PlaNYC,15 the city’s first recognition of climate risk and initial policies for climate adaptation. Lindsey works on neighborhood resilience supporting community organizations that are already doing much of the resilience work. A major challenge is that available funding tends to focus on recovery and is restricted to communities damaged in a disaster, for example, by Superstorm Sandy.

Solecki asked whether a process exists to evaluate the long-term implications of climate change, as decisions tend to be made in the short term. Lindsey discussed the multilayered approach taken by New York’s Office of Recovery and Resiliency to tackle coastal protection, strengthen infrastructure, fortify building stock, and strengthen the community’s ability to address both short-term and long-term priorities. An example of a short-term priority is investing in business resiliency; longer-term, the city is looking at projections to 2050 of impacts from sea level rise and heat waves to help guide decision making. To evaluate the long-term implications of decisions made in the short-term, New York City uses a Panel for Climate Change, a group created in 2008 made up of scientists who advise the mayor on long-term impacts.

Molloy responded that it would be nice to lay out a map of long-term, medium-term, and short-term impacts that makes sense chronologically. However, the reality is that communities have to be opportunistic about what is on their immediate horizon and turn them into opportunities. She provided an example of how most cities have a storm water permit, a wastewater permit, or consent for combining overflows—these could be opportunities to initiate forward-thinking efforts. For example, instead of building big tunnels to contain sewage, the city could build green infrastructure that provides multiple benefits.

Solecki asked the panelists to describe who should be at the table and what the starting point is of not only thinking about the everyday climate

___________________

15 See http://www.nyc.gov/html/planyc/downloads/pdf/publications/full_report_2007.pdf.

risk but also the longer-term challenges. Lindsey highlighted the importance of capitalizing on the current work of communities, some of which has been taking place for decades. For example, many neighborhoods, smaller community-based organizations, and faith-based community groups have organized around environmental justice for years. She described a grassroots climate adaptation effort in northern Manhattan with a very high level of community participation. Her role was not to go in as a city representative and tell them how to do climate adaptation, but rather to sit in the meetings, discuss resources, and connect them with other entities that could help them move forward. The city also takes a top-down approach, engaging religious and nonprofit leaders on a taskforce to develop recommendations on incorporating community groups in disaster recovery. Molloy suggested that it can sometimes be more productive to constitute groups not by requiring a representative from specific organizations, since a good number of those people may attend meetings only reluctantly, but to instead seek out those people with a desire to make a difference and contribute.

Solecki noted that, moving forward, climate change is going to touch the private sector more and more. He asked the panelists to talk about ways to engage the private sector in public and nongovernmental discussions on climate change. Lindsey mentioned the benefit for smaller towns to have platform partners that help fund projects and resiliency work such as with the 100 Resilient Cities partnership. McLeod said that The Nature Conservancy makes a business case for the ecosystem services that nature provides, highlighting nature-based solutions as one of the business strategies that achieve community resilience goals. A challenge is the lack of specific data on how natural systems perform; there is a need to create a record of performance of natural assets. The Nature Conservancy is in conversation with the insurance and financial sectors around creating value that builds resilience and meets some of society’s goals. Regarding metrics, they are working in collaboration with engineering companies and insurance companies to identify effective methodologies for measuring the value of natural systems. Molloy commented that the private sector has standard ways of doing things and companies are often skeptical about trying new things. She emphasized the importance of building a business case to demonstrate that an alternative can be an equal cost, less expensive, or just as profitable as standard business practices.

In response to Solecki’s question about opportunities or leverage points for regional action, Lindsey stated that Superstorm Sandy changed the conversation in New York and New Jersey. Because everyone could converge

around the issue of climate change and resiliency, collaboration became easier. In addition, the geography between the two states is similar and it was easy to bring people together around impacts since they have the same coastal risk, flood risk, and heat impacts. Molloy added that communities are starting to realize the possibility of doing projects less expensively on larger scales, and the value in implementing similar policies; for example, it would be more affordable if developers use the same measures in multiple locales.

Solecki’s last question asked the speakers to provide examples of good indicators or metrics of resilience. McLeod suggested metrics of injury, death, and business interruption. For example, a resilient community would only suffer a short interruption in its economic activities. For an individual, a valuable metric is days of work missed; for example, it is important that transportation corridors remain accessible to allow people to get to work. McLeod mentioned the use of mangroves to protect a main coastal road that frequently washes out. In Lindsey’s work on neighborhood resilience, she uses metrics related to social cohesion such as volunteer rates. She cited research showing that higher levels of civic group activity lead to more trust among members of a community; engaged residents are more likely to help a neighbor during an emergency. New York City also uses longer term metrics, such as those that track reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. Molloy noted that while the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency does have established metrics around water quality, she would like to get to the point where a carbon footprint calculator is used in decision making.

An audience member asked what tools or metrics of success are used when choosing projects to fund. Lindsey stated that recovery funding guides much of their work, and hence funds go to communities recovering from disaster, but they do try to couple it with research and resilience. McLeod mentioned that The Nature Conservancy uses a matrix of criteria; for instance, asking is the project a priority for the community, what is the landscape of participation and engagement in the community, and are there data to support that the solution can work?

An audience member spoke to the importance of cooperative research among the climate and weather science community, the engineering community, and the social sciences community to properly characterize what climate weather extremes will be in the future and understand the effects on the public. Systems need to be designed to a reasonable estimate of future climate weather extremes, so that they are adaptable to more severe conditions. Molloy agreed that there is a need for better climate projections going out 50 or 100 years and believes that projections are improving, but

added that in some ways it does not matter because communities have to keep adapting their systems anyway. In this sense, Molloy believes that green infrastructure has an advantage stating, “You put in some gray infrastructure and you’re stuck with it, and it’s really expensive to change. Whereas the benefit with the natural systems is that it’s easy to add more trees or whatever element it is.”

INCENTIVIZING RESILIENCE

Kevin Long, emergency management specialist with the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s Federal Insurance and Mitigation Administration, introduced the final session as an exploration of how we can continue to foster and grow resilience in communities, including incentivizing resilience in ways that resonate with different parts of a community, its residents, leaders, and businesses. Long introduced three panelists: Alex Kaplan, senior vice president of global partnerships at the reinsurance company Swiss Re; Sarene Marshall, executive director of the Center for Sustainability at the Urban Land Institute; and Sandy Fowler, assistant city manager of Cedar Rapids, Iowa, and asked them to describe some of their work related to incentivizing resilience.

Kaplan explained that Swiss Re, a global aggregator of economic and financial risk, has had a keen interest in risk and resilience since the early

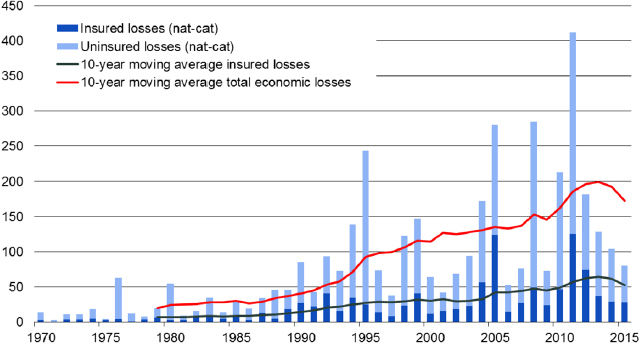

1980s when it created the position of a chief climate change officer. The cost of disasters is rising and uninsured losses are rising even faster, meaning that society, rather than the insurance industry, is picking up more and more of the price tag. As shown in the figure below, the growing burden of uninsured natural catastrophe losses from 1970 to 2015 (billions of dollars in 2015). He gave the example of the Japanese earthquake in 2011. Of the $403 billion in economic value destroyed in that calendar year, $126 billion was insured. He acknowledged that while changes in the intensity and frequency of storms were responsible for rising costs, the loss driver was the massive accumulation of assets in the most disaster-prone areas of the world.

Kaplan outlined the increasingly heavy costs falling on U.S. taxpayers. Since 2005, taxpayers have spent more than $300 billion in direct costs from extreme weather or wildfires. In 1991, 13 percent of the total U.S. Forest Service budget was for wildfire suppression; in 2013, it had increased to more than 50 percent of the budget. In 2012, the year Superstorm Sandy struck the East Coast, the U.S. government spent $96 billion on climate-related disaster losses, the single largest non-defense and non-discretionary spending line item in the federal budget. According to Kaplan, the U.S. government spent more on climate risk than on education or transportation.

Swiss Re and the Economics of Climate Adaptation (ECA) Working

Group16 are working to put a price tag on the risk cities face from climate hazards and examine how it evolves over time. Their aim is to equip decision makers with tools to identify the kinds of losses that can be expected over a specific period of time and determine how many of those losses can be averted, allowing decision makers to determine the optimal investments in adaptation measures. Swiss Re has implemented this methodology across the globe, including in New York City post-Hurricane Sandy when Mayor Bloomberg asked them to look at climate exposure in the present, in some future scenario, and how that changes over time. Through this work, Swiss Re found that “the annual expected weather-related loss for the five boroughs of New York City is estimated at USD 1.7 billion, increasing to USD 4.4 billion by 2055. The modeling suggests that the increase in losses is split evenly between losses driven by sea level rise and those driven by more severe hurricanes.”17 Kaplan stated that this is not indexing for inflation or economic growth but rather it is pure climate figures. With these data, the city has the tools to have a real conversation with the community because there is a money value associated with future loss and potential solutions to address those losses.

Kaplan described an initiative designed to help governments transfer risk from taxpayers—that is, the public balance sheet—to the private insurance market. The Caribbean Catastrophic Risk Insurance Facility18 serves the governments of Caribbean islands that suffer from frequent excessive rainfall, hurricanes, and earthquakes. These governments are unable to absorb the impact of those costs on their gross domestic product (GDP). With help from the World Bank, Caribbean countries pooled their resources and collectively bought insurance in the private market. The program uses parametric insurance, in which policy payouts are based on an environmental trigger such as wind speed or seismic tremors. In 2010, the Haiti earthquake triggered the policy. The payment was made within 14 days and had a dramatic impact on the government’s ability to respond. The payment constituted 50 percent of the funds the government received

___________________

16 The Economics of Climate Adaptation Working Group (http://www.swissre.com/eca) is a partnership among the Global Environment Facility, McKinsey & Company, Swiss Re, the Rockefeller Foundation, ClimateWorks Foundation, the European Commission, and Standard Chartered Bank.

17 Swiss Re. 2013. “Swiss Re provides expert input for New York City Study.” Accessed February 14, 2017. http://www.swissre.com/rethinking/climate_and_natural_disaster_risk/Swiss_Re_provides_expert_input_for_New_York_City_study.html.

18 See http://www.ccrif.org.

within the first 10 weeks after the earthquake. In Uruguay, where 80 percent of electricity production is from hydropower, parametric insurance safeguards the country’s energy supply against drought. The insurance structure effectively ties rainfall to the price of oil; if rainfall falls by X and oil prices are Y, the policy triggers $450 million dollars that can be used to make investments in alternative energy sources so that additional energy costs are not passed on to consumers. In Florida, parametric insurance connects wind speed exposure to a portfolio of assets, rewarding the insured for making better risk decisions by moving away from the coastline; conversely, the more assets are placed on the coastline, the higher the insurance costs.

Marshall introduced the Urban Land Institute (ULI) as a membership organization that works with real estate professionals to help the industry understand how to use land responsibly. Membership is diverse, including real estate developers, architects, investors, urban planners, landscape architects, engineers, property managers, and others. In addition to playing a convening role, ULI has a research and publication arm that aims to help its members do better in their communities—through their direct action and what they build—and be advocates and leaders. The Center for Sustainability is focused on both adaptation (managing the unavoidable risks in order to reduce vulnerability) and mitigation (trying to avoid the unmanageable), and is concerned with the integrated “three-legged stool of resilience,” which includes environmental, economic, and social risks. ULI and allied organizations representing 750,000 professionals have signed onto one definition of resilience: the ability to absorb and recover from adverse events. Resilience can be defined within the context of an extreme event or shock but also addresses long-term stressors and aims to enhance the “healthy immune system” of an entire community.

Marshall pointed to a recent project to create a business case for resilience, Returns on Resilience,19 in which ULI members contributed information about the climate risks they face in locations where they are engaged in building projects and ways to address the risk. The resulting case studies represent a diversity of real estate types and geographies; demonstrate how developers and others made resilient-relevant decisions, and how those decisions resulted in a better bottom line. The case studies are available as a written report and a Web platform. Marshall noted that developers still face challenges in obtaining good data and ways to articulate the value they extracted. However, she sees changes in how institutional

___________________

19 Returns on Resilience: http://returnsonresilience.uli.org.

investors think about risk in their real estate investments, which can affect the private sector’s ability to access capital, and thus constitute a significant incentive. Lastly, Marshall noted a program through which ULI members volunteer their time to help communities dealing with land-use and real estate challenges.

Fowler described the city of Cedar Rapids’ actions following a devastating flood in 2008 and destructive flash flooding in 2014. The 2008 flood covered 14 percent of the community including the downtown; 18,000 residents were displaced and 6,000 residences were significantly damaged; and 310 city facilities and other public institutions were flooded. All told, the community incurred $5.4 billion in damage. As part of the recovery, the city has taken steps to mitigate and prepare for future events, including acquisition of 1,300 residential and commercial properties, most of which were demolished; creation of 110 acres of greenway; and development of a flood-control system to protect the downtown, funded by state and sales tax increases over the next 20 years. The city also initiated an effort to increase the number of households with flood insurance; to make flood insurance more affordable, Cedar Rapids participates in FEMA’s Community Rating System.20 In addition, the city participates in a cross-jurisdiction watershed management project called the Middle Cedar Partnership Project,21 with partners that include The Nature Conservancy. The project engages farmers far north of the city in managing water on their land and incentivizing farmers to take land out of production and decrease run-off. The project benefits the city in terms of water quality as well as quantity.

In 2014, flash flooding highlighted the need to improve the city’s storm water management and update its undersized infrastructure, which was more than 100 years old. As a result, Cedar Rapids incentivized infiltration projects on private property by increasing storm water fees and then letting homes and businesses buy down their fees through actions taken on the property (such as installing permeable pavement). These incentives were also applied to city facilities, resulting in a platinum Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) library that retains 90 percent of the water on site in cisterns that feed a green roof, and the first platinum LEED central fire station in the country.

Long asked Kaplan about using incentives to show people where the

___________________

20 See https://www.fema.gov/community-rating-system.

21 See http://www.cedar-rapids.org/residents/utilities/middle_cedar_partnership_project.php.

less risky areas are, and if he had done that anywhere outside of New York. Kaplan mentioned that Swiss Re had looked at the economics of climate adaptation in all 77 counties and parishes along the Gulf Coast (Florida/Alabama border) down to Mexico, and found that they lose an average of 3 percent of GDP every year to infrastructure damages along the coast.

Long asked the panelists what challenges they encountered with their initiatives or incentive programs and whether there were common themes. According to Kaplan, one challenge is risk perception and how individuals, communities, corporations, and governments dramatically underestimate their exposure to risks and therefore choose not to take certain actions. Another challenge has to do with risk ownership; people assume that somebody else will deal with the problem. Marshall cited the need for a business case for resilience, to demonstrate not only the downside of not doing anything but the upside of doing something. This would allow people to create value for their project, for example, through being able to ask for higher rent or lower insurance rates. Marshall added that the ability to access capital is a big incentive for the private sector. For example, Miami developers that put in hurricane-resistant glass and were LEED gold certified, actions above and beyond the code, were able to lease building space twice as fast as competitor buildings, and saved $1 million on electrical costs annually.

An audience member asked the panelists to comment on how they communicate risk to their target audiences and in what ways they link that communication to actions that people can take to reduce that risk. Kaplan said that the insurance and reinsurance industries should change their language and adopt terminology that is understood outside of the industry. For example, the “100-year flood zone” terminology is misleading. People do not understand that living in the 100-year floodplain means they have a 33 percent chance of flooding in their home during the term of their mortgage. It is important to make it personal by putting the risk in dollar terms and make clear the ramifications of not taking action.

Fowler noted that a discussion about storm water fees got Cedar Rapids residents’ attention, and prompted robust discussions about ways they can decrease run-off and increase water infiltration on their properties. Marshall emphasized the importance of time scale—“the abstractions to a century from now are nearly impossible” for most people to understand—and highlighted the importance of putting risk in financial terms for the private sector. Long concluded with the importance of building trust and partnerships between federal agencies and local communities.