2

Linking Culture, Language, Behavior, and Data

Panel moderator Susan Weller, University of Texas Medical Branch, introduced the first workshop panel by explaining that three different approaches to studying culture, language, and behavior emerge from social psychology, anthropology, and digital research and network analysis:

- using a series of related questions about attitudes, beliefs, perceptions, etc., to identify individual differences and create typologies of people within a culture;

- using a series of related questions to estimate a group’s best response to each question, which allows for the examination of shared beliefs and behaviors as a way of identifying what is normative in a culture, a model that has proven adaptable to multiple forms of data and statistical approaches; and

- using naturally occurring or observed language, responses, and images to identify patterns and clusters of behavior at both the individual and group levels.

Presentations in this session illustrated how each of these approaches provides a unique way of understanding culture.

MEASURING INDIVIDUALS: HOW CULTURAL VALUES SHAPE PUBLIC PERCEPTIONS OF RISK

Dan Kahan, Yale University, presented his work on how beliefs and values can influence perceptions of science communication and the way

people process information about risk. Under a simple Bayesian model, he observed, individuals would revise an existing belief in proportion to how much more or less consistent it was with new evidence relative to some alternative belief. However, he explained, people do not think this way. Instead, he said, people are subject to confirmation bias, a phenomenon in which they assign weight to new evidence based on its consistency with what they already believe. He noted that this tendency limits the likelihood or speed with which people will revise mistaken beliefs.

Kahan and his colleagues have tested a model that helps explain how this bias may occur in the first place. According to this cultural cognition model, Kahan explained, people use their cultural worldviews—preferences about how society should be organized—to motivate their search for and processing of information. He added that people search for new information that is consistent with the positions of their affinity groups; in addition, “no matter where the information comes from, they are going to selectively credit it and discredit it in patterns that reflect and reinforce the position on some disputed policy fact within their group, and usually contrary to some competing group.” Because people repeatedly apply this strategy, he continued, they develop a set of prior beliefs about an issue, and confirmation bias comes into play because those prior beliefs are highly correlated with the way they select and process new information. However, he said, a third variable—cultural worldview—determines both prior beliefs and information seeking and processing.

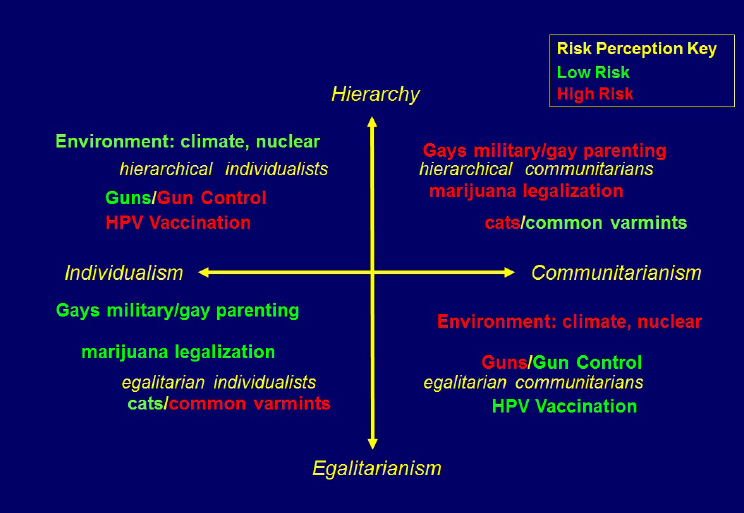

Kahan presented evidence that supports this model. He cited one study that examined the views about nanotechnology of a nationally representative sample of 1,850 people.1 He and his colleagues gathered survey data on participants’ worldviews to determine where they fell on a spectrum from individualism to communitarianism (the survey questions assessed the degree to which participants felt that individuals should be responsible for their own well-being, without the assistance or interference of the collective). The researchers also measured hierarchical and egalitarian views. Referring to Figure 2-1, Kahan explained that the interaction or combinations of people’s views on these dimensions tend to fall in patterns, which can be categorized in four groups that provide a powerful way to predict people’s risk perceptions. For example, he said, people who hold more communitarian hierarchical views (i.e., the upper right quadrant of the figure) tend to believe that the collective, represented by officials with rank and authority, should be securing the well-being of all individuals within the collective and overriding individual choices to do so. On the other hand, he noted, people with more egalitarian views believe authorities should not

___________________

1 Kahan, D.M., Braman, D., Slovic, P., Gastil, J., and Cohen, G. (2009). Cultural cognition of the risks and benefits of nanotechnology. Nature Nanotechnology, 4(2), 87–90.

SOURCE: Presentation by Dan Kahan at the workshop.

dictate individual choices. With regard to specific risks, he continued, the hierarchical individualist tends to be skeptical about environmental risk, whereas egalitarians and communitarians tend to be very concerned about those same risks.

To explore the impact of people’s worldview on their perception of risk, Kahan explained how the four different groups depicted in Figure 2-1 view gun control laws and regulations. Kahan and his colleagues found that those with hierarchical worldviews tend to view a gun as a piece of equipment that both provides its owner with status as a protector or hunter and reduces the risk of violent predation. In contrast, they found that egalitarians and communitarians perceive more risk to owning a gun and associate guns with patriarchy or assassinations of egalitarian leaders.

Kahan reported that the research showed similar patterns in the study participants’ views of environmental risk, but the researchers were also interested in participants’ reactions to a topic about which they were learning for the first time. To gather this information, participants were surveyed on the subject of nanotechnology. Kahan reported that although about 80 percent of participants had not heard of the technology or did not know how it is used, about 90 percent had an opinion on whether it

was safe. Kahan and his colleagues measured participants’ perceptions of the risks and benefits of nanotechnology, then assigned the participants to one of two experimental groups: one group received no information about nanotechnology beyond a minimal definition; the other received a single paragraph describing the benefits of nanotechnology and another describing some of its potential risks.

According to Kahan, the results of this experiment showed that about 61 percent of the group that received no information about nanotechnology perceived it as safe. Hierarchical individualists and egalitarian communitarians, who tended to disagree about environmental risk, did not differ significantly in their views about the risks of nanotechnology. However, Kahan reported, participants in the group that received information splintered in ways consistent with the patterns already noted in the views of hierarchical individualists and egalitarian communitarians regarding environmental risk.

In their study, Kahan and his colleagues also investigated the finding from other surveys that the more people know about nanotechnology, as determined by their self-reported familiarity with the technology, the more they like it. Participants in their study showed a similar pattern, Kahan reported: those who were more familiar with nanotechnology indicated more strongly that its benefits would outweigh its risks, whereas the positions of those in the group receiving information diverged, correlating with their cultural outlooks. He added that those who professed to be unafraid of nanotechnology were also less concerned about other potential risks, such as those posed by the Internet, mad cow disease, or private gun ownership. “It is not the case that learning about nanotechnology makes you not worry about other things,” he said, “There must be some third variable that is both making people familiar with nanotechnology and not concerned about those things.” He concluded that his team’s experiment supports the cultural cognition model, which suggests that people’s worldviews, rather than their prior beliefs, explain how they process new information about risk.

Kahan’s subsequent research has focused on identifying the particular mechanisms that bias the search for and processing of information, including the individual characteristics that accentuate or suppress this processing. Contrary to expectations, he explained, people who displayed the greatest proficiency in understanding scientific evidence (i.e., higher scores on measures of critical thinking, science literacy, or interpretation of quantitative information) were the most polarized on issues. He added that subsequent experiments showed that people use these skills to find and rationalize or dismiss information consistent with the views of their worldview group. When people indicate a high level of curiosity about science or interest in consuming scientific information, he observed, they tend

to be less polarized. Some evidence suggests, he noted, that professional judgment can limit the effects of worldview on information processing, but he suggested that this is an area requiring more study.

Kahan closed by suggesting several research questions that might be worthy of future study. With respect to the question of whether professional judgment provides a level of immunity from bias in processing information, he observed, it would be interesting to study professionals who evaluate and make policy related to national security risks. He also pointed to the potential utility of research on how institutional cultures create affinity groups that affect how people process information. “The affinity groups could be anything,” he elaborated. “They are ones that are important to people’s status because people will judge you based on holding beliefs that are characteristic of the group, and they become almost badges of identity and loyalty.” He suggested further that future research could perhaps examine the effects of group identity among people drawn to terrorism. He remarked that such questions could be explored through collaborations between researchers and professionals who work in national security settings.

EXAMINING SHARED BELIEFS AND BEHAVIORS: LIVING UP TO CULTURAL IDEALS

William Dressler, University of Alabama, described advances made in studying “cultural consonance,” which involves modeling the degree to which individuals’ own beliefs and behaviors are similar to the prototypes for belief and behavior encoded in the shared ideas and practices of a culture. He explained that the concept of cultural consonance is embedded in a larger body of theory about what culture is and how it affects groups and individuals. While an examination of this complex body of work was beyond the scope of the workshop, he noted that cultural knowledge is a property of a social group but is also possessed by each of the individuals in that group. Viewing cultural knowledge this way, he added, allows researchers to describe intracultural diversity; the differences between culture and individual beliefs and attitudes; and the relationships among human culture, behavior, and biology.

The cultural consensus model2 played a key role in advancing the study of culture, Dressler continued, because it provided a model for observing and measuring the knowledge that is shared and how it is distributed among individuals. He explained that research based on this model involved first testing the overall consensus among individuals regarding their knowledge of a cultural domain (e.g., family life), and then calculating an

___________________

2 Romney, A.K., Weller, S.C., and Batchelder, W.H. (1986). Culture as consensus: A theory of culture and informant accuracy. American Anthropologist, 88(2), 313–338.

individual’s degree of cultural knowledge based on this “cultural answer key” (i.e., consensus). He added that this model can also be useful for identifying culturally contested models or subcultures.

Dressler said he employs a two-stage process to study how people incorporate cultural knowledge into their own beliefs and behaviors. He first explores the cultural domains of interest to identify the content and structure of cultural models and to determine the degree to which these are shared among individuals. Second, he collects extensive survey data on the extent to which individuals hold this cultural knowledge (cultural consonance) and its association with health outcomes. Dressler described research he has conducted in Brazil to illustrate this approach.3

Dressler and his colleagues began by identifying cultural domains that were significant for people’s everyday lives in the Brazilian city of Ribeirão Preto: lifestyle, social support, family life, national identity, and occupational and educational aspirations. These domains, he explained, either arose in spontaneous conversations with people or were of specific theoretical interest in the study of health and disease. Dressler asked study participants to list words they associated with each cultural domain. For family life, for example, participants generated a list of terms they associated with a prototypically “good” Brazilian family (e.g., “love” and “religious”). To assess lifestyle, the researchers asked participants to describe valued material goods and leisure time activities (e.g., a house of one’s own or going to the movies) and to rank the terms that were generated by importance. The terms were also sorted by additional characteristics, such as whether they were positive or negative with respect to family life.

Dressler explained that the next step was to conduct a cultural consensus analysis, which involved asking respondents to rate the importance of each term associated with family life and lifestyle and then analyzing the correlations among the responses. These data were then used to create measures against which individual responses were compared. In the case of the lifestyle domain, Dressler and his colleagues developed a checklist of the terms identified as most important and used it to create a survey of family life that measured the respondents’ perceptions of their own families relative to each of those terms.

According to Dressler, “With this measurement model, we can draw a straight line connecting the spontaneous speech of Brazilians to a measure that orders individuals along a continuum derived from the way they themselves talk about the domain.” He explained that this measurement approach provides a high level of validity from the perspective of those

___________________

3 Dressler, W.W., Balieiro, M.C., and dos Santos, J.E. (2017). Cultural consonance in life goals and depressive symptoms in urban Brazil. Journal of Anthropological Research, 73(1), 43–65.

within the culture being studied and can be adapted to virtually any domain of interest.

Dressler continued by observing that even if there is a high degree of agreement about ideals within important domains in a culture, not everyone achieves these ideals. He and his colleagues developed an additional survey to examine the relationship of this “cultural consonance” to health outcomes, such as blood pressure and depression, at multiple points in time. They found that survey respondents who showed the lowest consonance with cultural ideals related to social support tended to have higher systolic blood pressure, a finding replicated after a period of 10 years.

Dressler added that consonance with family life ideals was also associated with a lower incidence of depression, a relationship even more pronounced for people from low-income neighborhoods. According to Dressler, this research shows that cultural consonance with ideals of family life plays a role in how the genetic predisposition for depression and its interaction with childhood adversity manifest in symptoms of depression. He added that in a 2-year longitudinal study he and his colleagues found that changes in cultural consonance were associated with changes in depressive symptoms. More recently, he and his team have found that cultural consonance in life goals mediates depressive symptoms relative to both socioeconomic status and a sense of one’s own personal agency.4,5 Moreover, he reported, other researchers have linked cultural consonance with other health outcomes, such as body composition, stress in pregnancy, and Internet gaming addiction.6 Research of this kind has pointed to the significant role of cultural domains in many cultures around the globe, he noted.

Dressler concluded by suggesting how this methodology could be used with more extensive forms of data collection. In his view, data for the second phase of his approach—measuring individual beliefs and behaviors—could be gathered in a variety of ways and organized in terms of cultural domains and elements derived in the first phase of the process, the cultural modeling phase. “It is through the cultural modeling phase,” he elaborated, “that we can locate groups and individuals in a cultural space of their own construction.”

___________________

4 Dressler, W.W., Balleiro, M.C., Ribeiro, R., and dos Santos, J.E. (2007). A prospective study of cultural consonance and depressive symptoms in urban Brazil. Social Science & Medicine, 65(10), 2058–2069.

5 Dressler, W.W. (2016). Cultural Consonance, Personal Agency, and Depressive Symptoms in Urban Brazil. Abstracts of the 2016 Annual Meeting of the Society for Applied Anthropology, March 29–April 3, Vancouver, BC, Canada.

6 Dressler, W.W. (2018). Culture and the Individual: Theory and Method of Cultural Consonance. New York: Routledge.

IDENTIFYING PATTERNS: UNDERSTANDING CULTURE THROUGH SOCIAL MEDIA

Dhiraj Murthy, University of Texas at Austin, described research in which he and his colleagues have measured aspects of culture using large sets of visual data (big data), as well as explored how information spreads through networks of people. He explained that they have combined this research with what they describe as in-depth contextualized analysis of social media content across a variety of social media platforms, such as Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, and WhatsApp.

Murthy began his description of this research by noting several challenges unique to studying culture through social media. First, he observed, the information available about users is incomplete. But perhaps more significant, he said, is that the data are often visual: textual data are far easier to gather and to code into categories relative to visual data, particularly when researchers are using very large datasets. Murthy explained that he has developed a method for coding large sets of images and videos so they can be grouped in categories, archetypes, or models for analysis, and that this method can be automated so it can be used at the big data level.

Another challenge, Murthy continued, is that algorithms used by such providers as YouTube and Facebook to determine what content people see are proprietary and inaccessible to researchers and others. He characterized this as a particular challenge to studying how media content influences people and spreads through networks. He noted that Twitter has been studied more frequently than other social media platforms in part because its interface facilitates gathering and working with its textual data. While some Twitter research has focused on sentiment analysis,7 Murthy has pursued ways to code social media information along other dimensions using an open coding model. He explained that closed coding systems (e.g., sorting into predefined categories) are easier to work with than open coding systems (e.g., sorting into categories created based on the information gathered). However, he said, although open coding models are “messy” and difficult, they allow researchers to develop explanations of phenomena that emerge from collected visual data and are not dictated by prior conceptions.

Murthy described his analytic techniques as both abductive and retroductive. He explained that abductive reasoning has been defined as “finding the best explanations among a set of possible ones,8 whereas retroductive

___________________

7 For more on Twitter research, see Zimmer, M., and Proferes, N.J. (2014). A topology of Twitter research: Disciplines, methods, and ethics. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 66(3), 250–261.

8 Abduction is used to determine a logical assumption, explanation, inference, conclusion, hypothesis, or best guess via observation. For more information, see Paul, G. (1993). Approaches to abductive reasoning: An overview. Artificial Intelligence Review, 7(2), 109–152.

methods are abductive approaches used to identify reasons and causes for possible explanations.9

As described by Murthy, the process for coding visual data is an iterative one that involves coding and repeatedly reexamining new data to test and refine categories and concepts suggested by the data. “What is happening in terms of this YouTube video or in terms of an Instagram image? . . . We cannot understand all the motivations for why someone is posting this type of content because we do not know a lot about them. We are dealing with very sparse data,” he noted. To determine how to classify visual information and to understand how information circulates among a network of people, he and his team conduct network analysis, using the hashtags associated with images or videos to understand how information diffuses across a network of people. Although identifying meaningful visual attributes currently requires human coding, he and his team are seeking ways to apply the codes they develop to big data methods or other uses. In addition to examining online content, they examine data associated with the specific social media application.

Murthy described an example of how this methodology has been applied. He explained that he uses YouTube because it is one of the few social media application programming interfaces (APIs) that is very open and allows for active access for weeks at a time, enabling researchers to accumulate large volumes of video data. Social media platforms play an important role in radicalization, he noted, and journalists have reported that the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) uses social media as a key part of its recruiting strategy. Therefore, Murthy and his colleagues sought to better understand the role of videos in radicalization. He added that although Islamic State content is regularly deleted from social media platforms, it is also quickly reposted. He and his team looked specifically at which types of videos include recommendations for additional radical videos, what linguistic or other markers could identify this radical content, and what methods could be used effectively to classify such videos.

Murthy and his team identified 15 video titles mentioned in news articles as officially attributed to ISIS. Of these, they were able to locate and verify 11 as Al Hayat videos (officially produced by ISIS), and they used these 11 videos as “seeds.” One example of a seed video was a “Mujatweet.” According to Murthy, such often-used videos were designed to be tweet-sized for YouTube and reposted by ISIS YouTube bots whenever they were removed. Other seed videos had a more documentary style, he noted.

Murthy explained that each of these seeds recommended additional videos, which in turn recommended still others, so he and his colleagues

___________________

9 For more on retroductive methods, see Olsen, W.K. (2012). Data Collection: Key Debates and Methods in Social Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

ultimately identified millions of videos, although this larger pool included both official ISIS videos and completely unrelated content (e.g., videos related to gaming). He and his team selected a sample of these videos, coded them according to their attributes, and developed a framework to explain patterns observed in the videos by coders. Murthy noted that this method is a way to reverse engineer the information being sought. He described the selection of content to be displayed to users in search results or as “recommended” content as a “black box.” Because researchers lack access to the proprietary search data used by YouTube and other platforms, he said, “We do not know what percentage of users explicitly search for ISIS content versus [experiencing] ‘accidental’ exposure.”

Murthy added that examining the YouTube API allows him and his colleagues to determine whether a video is recommending additional radical videos, and that this information can be used to create a map of connected videos. In addition, the researchers are able to capture information about whether a user has watched a particular video, although the interface does not provide access to user search terms. The video content recommended to users when they view radical videos is what Murthy uses as an outcome measure: “Even though I cannot see the keywords that people are searching, at least I can approximate in some ways or try to measure some of their experience and also see how the algorithm is behaving in terms of recommendation,” he said. The recommended video feature of YouTube, combined with its autoplay of the next recommended video, tends to lead people to watch many videos in a row, a finding confirmed by research on this tendency, he explained.

Murthy and his team compared a sample of videos that directly recommended official ISIS videos with a random sample of those that did not recommend any radical content and a random sample of YouTube videos. Videos in all three samples were coded for 11 attributes. For example, Murthy explained, all videos were coded as to whether they mentioned social inequalities in the Middle East or whether they were in Arabic. He and his colleagues used an algorithm10 to identify the relative power of different attributes in identifying the videos that recommended radical content. They found that the attribute that most accurately identified such videos was the use of an explicitly radical keyword (such as ISIS) in the title. This factor, Murthy reported, predicted 35 percent of recommendations. He noted that combinations of attributes offered additional identifications: For example, videos that included content from a newscast, were recent, were in English, and came from an organization rather than an individual were also likely to make radical recommendations. This analysis, he said, showed that YouTube’s algorithms for suggesting content to users give high priority to

___________________

10 Ragin, C.C., and Davey, S. (2009). fs/QCA. Irvine: University of California.

content that is very recent, which may help explain why ISIS bots and individuals continually repost videos. Murthy described his results as somewhat surprising because “it should be really easy for YouTube to figure this out and have filtered this years ago.”

DISCUSSION

Following the presentations summarized above, panelists participated in a discussion and responded to audience questions. The discussion revolved around several topics: (1) understanding variability within and across cultures, (2) the impacts of new technology on culture and its role in measurement, and (3) the challenges of measuring cultural phenomena.

Understanding Variability Within and Across Cultures

The importance of investigating culture as a way to understand varying behaviors and actions in context was highlighted in the open discussion. As Dressler pointed out, “the concept of culture has become more important to more people because there is a gap in explanation” for changes in society.

One participant highlighted the need to capture variability within cultures, noting that even individuals can hold conflicting beliefs at the same time. Kahan observed that many people hold simultaneously conflicting beliefs, including scientists whose religious beliefs conflict with their scientific practices. A belief, he explained, is part of a larger cluster of desires, values, and goals that enable people to function in a particular context. In Kahan’s view, new research methods are needed to study these conflicts in values.

Murthy explained that he sees culture as socially constructed, created from the collective views that are developed and maintained within a society or social group and from the interaction of different views and ideas within the group. Different social media platforms engender a variety of social media cultures, he asserted, which affect how people behave and express themselves. He gave the example of platforms where people can post anonymously, which often lead to more negative and vitriolic posting. He explained that his work to understand how these online cultures intersect with radicalization focuses on the attributes of anonymous videos that may speak to particular cultural practices. Several cultures interact in these videos, he added, including gaming culture and conservative Islamic culture. He noted further that YouTube cultures are always evolving.

Researchers may have their own views as they seek to interpret the meaning of others’ culture, suggested one participant. Dressler said his work focuses intentionally on understanding culture from the perspectives of its members. He explained that even in the face of a high degree of con-

sensus about a domain of culture, his methods enable the identification of contested features and subcultures within a culture. To illustrate this point he cited Brazilian culture, in which working-class families tend to place greater emphasis on the importance of structure, organization, and rules in family life, whereas middle-class families emphasize affective and emotional climate. He added that some of his work on cultural models was conducted and repeated over time, demonstrating the stability of the models. This stability was surprising to him because the transition from a military dictatorship to democracy and the stabilization of the nation’s currency occurred within the same 10-year period. However, he noted, his methodology also showed change over time in the lifestyle domain of Brazilian culture; by 2011, information technology (e.g., having a cell phone or Internet access) was emphasized as important for a good life, and traditional face-to-face socializing had decreased in importance.

Kahan argued that while cross-cultural studies are very valuable, researchers need to ensure that the same constructs (e.g., ideas about what is risky) are being measured across the cultures. He explained that he examines the relationships among variables, looking for similarities in patterns across cultures, instead of seeking survey items that might be translated directly from one culture to another. Indicators of a particular attitude vary across cultures, he noted.

Impacts of New Technology

One participant asked the panelists to consider whether technological changes have changed the role of culture. Perhaps the role of culture is shifting from helping people fill gaps in information to helping people filter “noise,” he suggested. He speculated that this may be because culture is increasingly self-reinforcing within groups given that so much information is readily available. Kahan explained that in a pluralistic society that is increasingly successful in producing advances in science, a challenging communication environment involving communications among multiple groups who are in conflict with each other becomes more likely. “You add to that the conflict entrepreneur who understands these dynamics too and wants to promote the problem,” he said, “. . . therefore, we need even more effective ways of certifying knowledge across these groups.” He observed, however, that culture does more than help make people aware of what is known collectively and orient their views around that knowledge; it also fills a basic human need to understand what a good life with others looks like.

Another participant asked the panelists to consider the broader role of the rapidly changing information environment in culture, including whether it is causing an increase in attraction to radical ideologies. Murthy replied that many algorithms operating in online environments, such as

those of Amazon and Netflix, are designed to lead to echo chambers—to identify new content that users are likely to be drawn to based on their past choices. In the case of YouTube, he noted, people can begin with innocuous searches and be led to radical content. “Algorithms are value neutral,” he said. “If we are making an argument that increasingly our sociocultural dynamics are governed by information communication technologies, which are algorithmically shaped…then we have echo chamber dynamics that we have to largely take into account.” He added that these technologies are highly effective from a technical point of view, but they affect polarization and sociocultural dynamics. Weller pointed out that relative to cultural values, attitudes and opinions are more flexible and likely more subject to change and polarization. The information people consume may reinforce attitudes or opinions, she asserted, but not necessarily shift their cultural values.

Murthy also noted that online platforms have some unique features that appear to affect culture. First, he said, the design of the platforms shapes how people engage in the form of likes and comments. He added that these parameters also foster a certain global uniformity: “There is also a certain homogeneity, which I am seeing in my research increasing. That is also partially why ISIS just has to add subtitles on videos. They do not actually have to create new videos for particular cultural contexts, which means that they can be efficacious all around the world.” According to Murthy, algorithms in closed platforms are creating some homogeneity in culture, and he added that “from a measurement point of view, it may be a boon because we could then generalize [findings] from a particular cultural context [to other contexts].”

Challenges of Measuring Cultural Phenomena

Dressler observed that the cognitive sciences have made important advances in the ability to conceptualize and measure cultural phenomena by breaking down concepts into manageable components, yet approaches to this research continue to evolve. The amount and types of data sources are changing, noted panel moderator Susan Weller. For example, a participant suggested, changes in the approaches to studying culture may be necessary as people’s willingness to participate in survey research declines. Such changes may also necessitate greater reliance on new sources of data, she added. Weller noted further that the availability of large quantities of data enables the use of different approaches, moving away from methods that rely on agreement among individual subjects in their responses to survey questions. Dressler expressed the view that ethnographic approaches that involve working to understand meaning in a culture from the perspective of local individuals will continue to be needed to construct cultural models.

Even with small sample sizes, he asserted, it is possible to identify areas of cultural consensus that are generalizable to the population. He suggested as an interesting area for future research exploring how models uncovered by ethnographic methods could be connected with patterns that can be identified by analyzing large data sources.

Kahan observed that researchers are also seeking the most cost-effective ways to gather data, whether, for example, through such online sources as Mechanical Turk (MTurk),11 samples recruited through public opinion firms, or random digit dial surveys. However, he emphasized that future research methods should include continually seeking to confirm the validity of different sampling approaches to ensure that studies are accurately reflecting the “real world.” He argued that convergent validity based on multiple methods is best, but at the same time, he “would not trust any of our studies if they were not rooted ultimately in the ethnographic methods.”

___________________

11 See https://www.mturk.com/mturk/welcome [January 2018].