2

Status, Power, and Reputation

Presentations in the first workshop session addressed the international security implications of status, power, and reputation among both state and nonstate actors. Suzanne Fry of the National Intelligence Council (NIC) then offered reflections on the presentations and suggested topics for research that would benefit the Intelligence Community (IC). The panel closed with an open discussion between the presenters and audience members.

STATUS IN INTERNATIONAL SECURITY

Observing that “status” is commonly defined as an actor’s position in a social hierarchy, Steven Ward, Cornell University, provided an overview of how this phenomenon applies to states in the context of international politics. He reviewed the way the term is used by researchers, presented some key findings from emerging research in this area, and offered his ideas about future research directions.

For a state, Ward explained, status could mean membership in an elite club of states, such as the great powers or the West, or rank in an ordered list. Status cannot be achieved unilaterally, he added: a state’s position in the hierarchy must be granted by others through active accommodation. Furthermore, for status to be meaningful, it must be recognized by other relevant actors.

Status, Ward continued, overlaps with the concepts of power and reputation, but there are important differences. A state with power, he elaborated, has influence over outcomes because of its material capabilities; power is not dependent on the recognition of others. Thus, he said, a

state can satisfy its ambition for more power without having to convince others that the ambition is legitimate. Ward acknowledged that some scholars view the boundary between status and power as less distinct because status produces influence, which in turn is a kind of power. In any case, he added, status hierarchies are shaped by the distribution of power in the international system.

Like status, reputation also depends on the assessment of other actors regarding the value of a state’s attributes, Ward explained. But because status refers to a state’s position in a social hierarchy, he continued, one state’s gain generally corresponds to a loss for others—a phenomenon that does not apply to reputation. Moreover, whereas reputation is valued primarily as a tool that can be used for leverage in the international system, the acquisition of status is often regarded as a foreign policy objective.

“What justifies the growing focus on status among analysts of international politics?” Ward asked rhetorically. He observed that recognition of status as an important driver in international politics can be traced back at least to the 5th-century historian Thucydides. The current interest in status, he suggested, reflects insights from such fields as behavioral economics and social psychology, which have amassed a significant amount of empirical evidence showing that human beings care about their standing and the standing of the groups to which they belong.

According to Ward, researchers have established both that states care about their own status and that concerns about status have their own influence on foreign policy apart from issues of security and power. This point might seem trivial, he acknowledged, but researchers have demonstrated that this intangible phenomenon can make a difference in international politics. Rising powers are especially sensitive to status concerns, he added. He explained that, although scholars do not necessarily agree on the reason for this sensitivity, it has long been understood that unsatisfied status ambitions and disruptive foreign policies are strongly linked. Researchers have also explored ways in which states seek status through both violent and peaceful means. As an example of the latter, Ward pointed to the positive association between Olympic medal performance and the accumulation of diplomatic ties (such ties are used as a quantitative measure of status).

Ward then turned to important questions about status that remain unanswered. First, he said, although rising powers are known to prize international status, little is known about how status concerns affect other types of states, such as small states. Such research, he asserted, would be useful in understanding how status concerns may be implicated in disputes, such as that between Qatar and other Gulf states. Another unanswered question, he continued, is whether status has any instrumental value. While it is assumed that high status induces deference in other states, he elaborated, there is no evidence to prove this assumption is true. He views this as an

important question for policy makers who may be wondering about the extent to which they should be concerned about status abroad. Next, he pointed out that, although it is well known that states care about status, scholars do not yet understand why. This is another area, he argued, that has been characterized by assumptions rather than evidence. Perhaps the most important policy implication from recent work on status, he suggested, is that “a great deal of conflict could be avoided if established powers were willing to accommodate the status ambitions of rising powers.” However, he added, researchers have not systematically established what accommodation is and how it works, so it is impossible to say, for instance, “what American accommodation of Chinese status ambitions should look like, or what its costs might be.”

Ward closed by offering his expectations for future research in this area. He anticipates that new experimental work will test theories of status related to individual attitudes and behaviors, and also develop improved quantitative measures of status. He also expects to see more research on the role of status anxiety among regional or middle powers and states facing relative decline, and on the links between international status and domestic politics. Research on status, he cautioned, is vital because “status concerns might be . . . wrapped up in questions about regime vulnerability and nuclear proliferation in places like North Korea and Iran.”

SHIFTING POWER AND THE LEGITIMACY OF THE INTERNATIONAL PECKING ORDER

Social identity theory is a tool for understanding reputation, power, and legitimacy in the international system, observed Deborah Larson, University of California, Los Angeles. This theory, she explained, accounts for people’s behavior through a focus on their social identity, that part of their self-concept that is derived from being a member of a social group. When people’s self-image is closely tied to a group, she continued, they want that group to be viewed as superior and distinctive relative to other groups. Individuals experience their group’s triumphs and defeats as if they were their own, and they evaluate their group’s status by comparing it with that of a reference group that is similar but slightly higher in rank. For example, it is likely that Russia and China compare themselves with the United States, India compares itself with China, and France compares itself with Germany.

Larson continued by observing that groups (such as states) that regard themselves as having lower relative status may use identity management strategies to improve their ranking. One such strategy, she said, is to pursue social mobility. Thus a state may hope to gain membership in an elite group by following recognized rules and improving its standing on valued attributes. For example, Larson noted, at the end of the Cold War, central

and eastern European states withdrew from the Warsaw Pact and adopted democracy and liberal capitalism to gain entry into the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the European Union (EU), which were considered to have higher status.

A second strategy for improving relative status, Larson continued, is social competition, used when a group strives to equal or surpass a dominant group. This strategy may be used, she explained, when a group believes that the boundaries of the dominant group are impermeable and that the status hierarchy is illegitimate or unstable. For example, she said, a status hierarchy would be considered illegitimate if high-ranking members were perceived as having double standards or bullying other states. And an indicator that a status hierarchy was unstable would be if lower-status powers were consistently demanding greater influence over the rules and norms of the international system.

Larson explained that, in this geopolitical version of social competition, a challenger state will compete with elite groups over allies, client states, and weaponry. This situation can lead to conflict, she asserted, if other states see the challenger state as a threat. She added that, if the challenger state is not powerful enough to surpass the dominant state, it will act as a spoiler by trying to humiliate the higher-status state or prevent it from attaining its goals. She cited Russia as a current example, suggesting that it is acting as a spoiler because it lacks the military or economic power to overcome the United States, although its leader, Vladimir Putin, perceives the status hierarchy as illegitimate because Russia is not included as a leading power.

A third strategy for elevating the status of a state, according to Larson, is social creativity, which can take two forms. First, a state may seek to change the perception of a trait traditionally seen as negative. Larson cited the example of Xi Jinping, the leader of China, who promotes Confucianism, a philosophy once criticized by the communist leader Mao Zedong. She added that China has also demonstrated the social creativity strategy through its policy of pursuing increased power without posing a threat to other countries. Alternatively, she continued, a state may attempt to excel in a new dimension, as did former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev. Gorbachev “used social creativity in his attempt to achieve preeminence for the Soviet Union as leader of a New World Order based on . . . new thinking [about] . . . mutual security, nonuse of force, and nonoffensive defense,” she explained. This approach to social creativity is used, she elaborated, when the dominant group is impermeable, while the existing status hierarchy is believed to be stable (change in the hierarchy is unlikely) and legitimate (its norms are considered fair). However, she noted, if the dominant state refuses to recognize the new dimension as valuable or the aspiring state as superior on that dimension, social creativity is not effective.

Larson emphasized that a state using social creativity must have a minimum level of “hard power,” or military capability. As with social competition, she observed, a state’s attempt at social creativity can result in conflict. She asserted that examination of the above strategies for challenging international hierarchies demonstrates how international stability depends on two factors. First, if aspiring powers are to continue to believe in the stability of the current status hierarchy, she explained, the United States must maintain its overall superiority. However, she added, aspiring powers must also perceive that is it possible for them to be admitted into an elite group if the status hierarchy is to maintain its legitimacy.

Larson closed by sharing her thoughts on future research. She noted that a number of researchers are studying status among rising powers, such as India, Brazil, and Turkey, and reiterated Ward’s assertion that more research is needed on the uses and limitations of status incentives. She added that research is also needed to understand how the status ambitions of smaller states, such as the Balkans, Serbia, and Montenegro, can be accommodated within the current system. Finally, she called attention to the increasing interest in trust and trusting relationships. For example, she noted, mistrust is often an obstacle to resolving disagreements between states. Accordingly, she suggested, it is important to understand the modalities of building trust and what kind of institutional arrangements might substitute for trust.

MEASURING REPUTATION, POWER, AND STATUS IN NONSTATE ACTORS

Observing that reputation, power, and trust are also important for nonstate actors, Amanda Murdie, University of Georgia, explored how these phenomena can be measured in the context of such groups. The term “nonstate actors,” she explained, encompasses “good guys,” such as nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), including, for example, Amnesty International and Greenpeace, and traditional “bad guys,” such as terrorist groups, drug cartels, and rebel groups. She added that individuals, such as Angelina Jolie and Leonardo DiCaprio, who play a role in international affairs are also considered nonstate actors. She clarified, however, that the term does not encompass states or organizations established by states, such as government-organized nongovernmental organizations (GONGOs); intergovernmental organizations (IGOs); or organizations and individuals representing political parties.

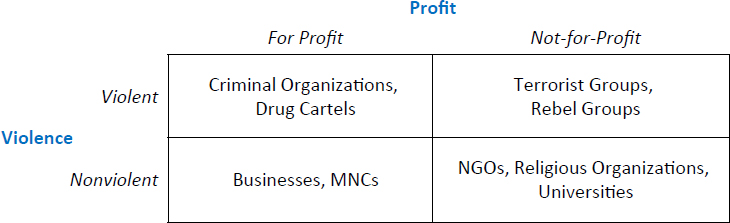

Murdie explained further that nonstate actors can also be distinguished by whether they are (1) typically violent or nonviolent, or (2) for-profit or not-for-profit. She illustrated this point with a two-by-two table, which demonstrates these divisions for such nonstate actors as drug cartels (typi-

NOTE: MNCs = multinational corporations, NGOs = nongovernmental organizations.

SOURCE: Created by Amanda Murdie for the workshop.

cally violent and for-profit) and NGOs (typically nonviolent and not-for-profit) (see Figure 2-1). According to Murdie, it is generally accepted that nonstate actors have a central toolkit they leverage to affect foreign policy and international security. However, she said, the distinctions displayed in Figure 2-1 can be blurred when organizations change tactics to effect change. For example, she elaborated, an actor that is nonviolent and not-for-profit in one situation may use a different tool in another.

Murdie analyzed data derived from the Teaching and Research on International Policy (TRIP) survey to develop an overview of the research on nonstate actors. This survey, initiated in 2003, is examining connections among teaching, research, and policy in international relations.1 Murdie explained that the developers of the survey also maintain a database of coded publications in leading international relations and political science journals from 1980 to 2015. She found that 10 percent of all articles included in the survey are focused on nonstate actors. Although this is a small percentage, she emphasized that interest in nonstate actors has grown significantly since 1980. There has also been an increase in quantitative research methods and systematic measurement since 2008, she observed. However, she added, despite recent work on terrorist groups, NGOs, and religious organizations, the influence of violent for-profit organizations and individual nonstate actors on international security has been largely ignored.

One method of measuring nonstate actors, Murdie noted, is to count the number of organizations. While this may appear to be a straightforward method, she said, organizations working in repressive regimes frequently change their names to stay under the radar. Another research approach is

___________________

1 For more information on the TRIP survey, see https://trip.wm.edu/home/index.php/about-us/what-we-do [January 2018].

to measure the outputs of such groups, although the nature of their outputs varies. For example, Murdie explained, the output for a nonviolent, not-for-profit organization might be the dissemination of a product, such as a press release or report, whereas the output for a terrorist organization might be the number of terrorist events or the lethality of those events. She added that the level of media attention these outputs receive is an indicator of status, power, and reputation.

Murdie has also explored how the status, power, and reputation of nonstate actors are perceived by others in their community, as well as by outside actors, such as states and IGOs. Some large, prominent NGOs, she noted, have sufficient status that they can act as gatekeepers on the international stage and help determine which issues receive international attention.2 Other groups may claim connections to higher-status organizations as a way of increasing their own stature.

Murdie closed with a look at possible trends in future research. She suggested that big data and advanced machine learning techniques, which are increasingly accessible to researchers, should be used to evaluate well-known, but untested, theories. In her view, more research is needed on the international significance of violent, for-profit criminal organizations, as well as on individual nonstate actors, such as celebrity activists and religious leaders. She also hopes that researchers will focus on nonstate actors that transition from violent to nonviolent methods. She added that a new dataset, NAVCO 2.0,3 which tracks violent and nonviolent campaigns and changes in their tactics over time, would be a valuable resource for such work.

Nonstate actors have a growing role in complex emergencies and counterinsurgencies, Murdie noted, and it is not uncommon for military actors, NGOs, and rebel groups to be in contact during conflicts. She suggested that research is needed to understand how status, power, and reputation are affected by these complex relationships.

Finally, Murdie pointed out that, since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, there has been a steady decline in civil society, by which she meant the influence of NGOs and similar social organizations. States may intend to prevent funding from reaching terrorists through nonstate actor networks, she noted, but some countries are taking the opportunity to restrict even groups that operate on a strictly neutral humanitarian level. She

___________________

2 Carpenter, R. (2010). Governing the global agenda: “Gatekeepers” and “issue adoption” in transnational advocacy networks. In D. Avant, M. Finnemore, and S. Sell (Eds.), Who Governs the Globe? (Cambridge Studies in International Relations, pp. 202–237). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511845369.009.

3 For more information on the University of Denver’s Nonviolent and Violent Campaigns and Outcomes (NAVCO) Data Project, see https://www.du.edu/korbel/sie/research/chenow_navco_data.html [January 2018].

suggested that research is needed to understand the factors that have led to such crackdowns and how they are affecting nonstate actors.

REMARKS FROM SUZANNE FRY

Fry began her reflections on the three presentations of this panel by introducing the audience to the NIC’s quadrennial Global Trends4 series, an unclassified publication aimed at assessing the implications of global trends and uncertainties. She reported that this publication has documented an increase in the number and diversity of actors benefiting from the diffusion of power. States, she observed, used to be the primary holders of power, but analysts are now seeing power diffuse to nonstate actors, such as organizations and individuals.

To address the implications of this change, Fry argued, scholars should consider developing theories that take into account multiple types of actors, including IGOs and political parties. She seconded Murdie’s suggestion that theories are needed to examine the disruptive effects of understudied violent, for-profit groups, such as drug trafficking organizations. She also agreed with Larson that social identity theory can help researchers understand the strategic choices such actors make. However, she cautioned that researchers should not limit the application of their theories to a single scenario. Unlike analysts, she noted, researchers do not have the benefit of having access to all-source information, a limitation that could cause them to be guided by inaccurate assumptions. Thus, she urged researchers to apply their theories across a range of scenarios. Moreover, she suggested that in considering such issues as status, researchers should look across cultures.

In Fry’s view, theories that “seek to explain how these various actors affect outcomes that matter for national security” should also be a high priority for researchers. She observed that many in the IC speculate that nonviolent nonstate actors, such as faith-based charities and Human Rights Watch, play a significant role in the international system, but that evidence demonstrating specific outcomes, such as a reduction or increase in violence, is needed to validate this hypothesis. Similarly, she suggested that, rather than thinking about power in relation to capability, researchers should think about power in relation to outcomes. While such attributes as military size or population size are important, she said, it is also critical that researchers explain what outcomes are associated with these attributes. She noted that in real-world applications of theory, analysts will often combine multiple theories to understand changes in the geopolitical landscape. Thus, she concluded, using case study research to review significant moments of

___________________

4 For more information on the NIC’s Global Trends, see https://www.dni.gov/index.php/global-trends-home [January 2018].

political change and test the explanatory power of various theories in those moments could be helpful to analysts.

DISCUSSION

Workshop participants raised several questions related to status. One question was how status-seeking behavior within nonstate actor organizations compares with that of states. Murdie responded that some public administration research has looked at status within NGOs. However, she noted, less research has examined the internal relationships in terrorist and rebel groups. In particular, she suggested, more research is needed to understand where terrorist and rebel leaders get their power.

Another participant questioned how much researchers know about variations in status concerns across states. Ward and Larson suggested that status concerns are often a mix of historical status and identity. For example, Larson noted, for thousands of years there was no rival to China’s power. Ward agreed, and added that, although this is no longer the case, China is still very sensitive to status because there was a time when it was the leader in terms of status and power. Furthermore, Larson observed, countries that are in proximity to one another, such as China, Japan, and India or Brazil and Argentina, will often develop rivalries as a result of culture and history. Murdie added that terrorist organizations are also sensitive to status. After an attack, she noted, leaders will scour media sources to see how many times their group is mentioned in relation to the attack. Ward followed up on Murdie’s point by suggesting that more research is needed to understand variations in status among individual actors.

One participant asked how to distinguish between status and prestige. Ward and Larson responded that they have differing views on this topic. Ward defines prestige as reputation for power, whereas status is culturally contextual and can be based on things other than power. Larson, on the other hand, sees prestige as “any sort of quality that the international community values,” while status is hierarchical. “You don’t talk about somebody having first-class prestige or second-class prestige,” she said, “but you do talk about first-class and second-class powers.”

A participant asked whether the panelists could identify examples in which only status could explain an outcome. Ward responded that German battleship building before World War I and the 1933 departure of Japan from the League of Nations both evolved from status-seeking behavior.

A final question concerned how status is disputed or conferred among states. A participant wondered whether the status hierarchy could become permeable if a dominant state were to guide a lesser state on relevant issues, and what might be learned about this from the transition of power from Britain to the United States over the course of the 19th and 20th cen-

turies. Larson responded that accommodation depends largely on whether the dominant state is powerful enough to impose its views on a state with lesser status. However, she added, more research is needed to answer this question. With regard to British accommodation of the United States, she suggested that the transition of power from Britain to the United States was not necessarily a smooth one. Britain did not accept that its status had been reduced, she argued, until the 1956 crisis over the Suez Canal.