7

Intergenerational Transfers and the Older Population

INTRODUCTION

Economic behavior varies in fundamental and important ways over the life cycle. Early, and again late in life, people consume more than they produce through their labor. In between these two phases of the life cycle, people produce more through their labor than they consume. The life cycle gives rise to institutions and economic systems that facilitate the reallocation of resources from one age to another. Intergenerational transfers constitute an essential part of the reallocation system, with governments and families playing distinctive roles. Families play a central role in child rearing with large intergenerational transfers of money and time from parents, and to some extent grandparents, to children. In some societies, intergenerational family transfers are also an important part of the old-age support system. Governments also are heavily involved in intergenerational transfers through public programs for education, health care, and pensions. Assets, in their varied forms including debt, provide another mechanism by which resources can be shifted from one age group to another. Young people can consume more than they produce by relying on credit—student loans or credit card debt, for example. Seniors can rely on wealth acquired

___________________

1 Corresponding author.

2 The authors’ research for this paper was funded by the National Institutes of Health, NIA R24 AG045055. We are grateful to Michael Abrigo, Gretchen Donehower, and other members of the NTA network whose estimates we used. The researchers are identified and more detailed information is provided on the NTA Website: www.ntaccounts.org. See also Lee and Mason (2011) and United Nations Population Division (2013).

when younger, through bequests or life-cycle saving, to support themselves in old age.

People are deeply altruistic. They care about the well-being of others, particularly family members but even strangers. Intergenerational transfers are an important manifestation of altruism that serves multiple, essential functions in all contemporary economies. Achieving distributional objectives—for example, that children and the elderly do not live in poverty—depends on intergenerational transfers. Achieving economic growth and ensuring the welfare of future generations depend on parents and taxpayers investing heavily in the upbringing of children.

Systems of intergenerational transfers will experience considerable stress due to the unprecedented changes in population age structure discussed briefly in the next section. These effects will depend in part on why intergenerational transfers occur. So in the next sections we discuss the determinants and then economic consequences of intergenerational transfers from a theoretical perspective. Then we consider empirical patterns and projections of public and private intergenerational transfers around the world, drawing on National Transfer Accounts (NTA) estimates (Lee and Mason, 2011; United Nations Population Division, 2013). We conclude with a discussion of policy responses.

THE CHANGING DEMOGRAPHIC AND ECONOMIC SETTING

Demographic forces are important for any system of intergenerational transfers because they determine the numbers of those giving transfers and those receiving them. Transfers given must always equal transfers received; hence, changing population age distributions require adjustments in the per capita donations or receipts. Economic forces are important because they influence the resources of those giving transfers and the needs of those receiving them. The future of intergenerational transfer systems will ultimately depend on the interplay between demographic and economic forces. If they are mutually reinforcing, many countries will experience population aging and slowing economic growth with profound implications.

Although population growth and age distributions are affected by fluctuations in fertility and mortality, such as the U.S. Baby Boom, the big story is the demographic transition: the shift in mortality and fertility from high to low values. The demographic transition has been under way at the global level for about two centuries, but with very different timing and extent at the level of regions and nations. The transition leads first to rapid population growth and young populations. Next comes an era with rapid growth in the working-age population, often referred to as the demographic dividend. Population aging is the last stage of this process. Before the transition, roughly 4 percent of the total global population was age 65 or older (Lee,

2003, p. 168). In 2015 the share in Japan, the country with the oldest population, was 26 percent and is projected to rise to 37 percent in 2055 (United Nations Population Division, 2017, henceforth UN 2017). For the high-income countries as a group, the share will still be rising in 2100 (from 17.0% in 2015 to 31% in 2100; UN 2017). The rapid population growth that occurs during the transition has been replaced by decline in some high-income countries. Japan is already experiencing population decline, as are Eastern and Southern regions of Europe, and many other countries are expected to follow, with Eastern Asia projected to begin to decline in 2030–2035 and the more developed regions as a whole in 2045–2049 (UN 2017). The United States is somewhat exceptional among high-income countries, with slow population growth expected to persist for many decades.

Standard measures of population aging, including those used above, are based on chronological age. With improving health and vitality at older ages, alternative measures of aging are being explored. Measures based on mortality, disability, self-assessed health, or time until death (Sanderson and Scherbov, 2010; Coile et al., 2017) suggest that functional population aging is barely occurring at all. After an extended period of decline, the observed age at retirement has also been rising in most OECD countries since the mid-1990s. However, a countervailing trend in many countries is an increase in consumption at old age that often exceeds the additional resources produced by the elderly.

Responding to any increase in the number or needs of the elderly will prove to be much easier if economic growth is robust. Nondemographic factors will play a critical role here, but population change is also likely to prove important. Labor supply, saving, and asset-holding vary by age, so the number of people at each age influences the aggregate supply of labor and capital—and over time, the growth rates and levels of aggregate output, wages, and interest rates (rates of return on assets). Because the working-age population is growing more slowly or declining in many countries, in the absence of higher rates of labor force participation labor supply will grow more slowly or decline and total output growth will slow. Because assets are disproportionately held by older adults, capital is likely to rise relative to the number of workers. As capital increases relative to labor, wages will likely rise and interest rates decline (or remain at currently low levels). The increase in physical capital per worker may be reinforced by growth in human capital because lower fertility facilitates greatly increased human capital investments per child (Becker and Barro, 1988; Mason et al., 2016). Thus, demographic change likely will lead to slower growth in total output but more rapid growth in output per worker.

The effect of population on output per worker is not the entire story, however. First, the number of workers relative to the number of people (the support ratio) varies over the demographic transition. During the aging

phase the support ratio is declining and, hence, output per capita grows more slowly than output per worker.

Second, the division of output between consumption (meeting current needs) and saving and investment (meeting future needs) varies. Higher saving rates are often proposed in preparation for population aging because they would spur more rapid economic growth and allow the elderly to depend less on old-age transfers. However, as Cutler et al. (1990) pointed out, if saving rates are high enough, saving more sacrifices current living standards with little or no benefit in the future. Moreover, the saving rate that maximizes per capita consumption is lower when the labor force grows more slowly. For this reason, aging societies can devote more of their resources to current standards of living and less to future needs. One possibility, then, is that lower saving would benefit the economy, whereas higher saving is needed to meet retirement needs. Under these conditions, expanding public transfer programs could eliminate the conflict by reducing the saving needed for retirement needs. Another possibility, and one that is quite likely, is that current saving rates are less than needed by the economy. Under these circumstances, policies that encourage higher saving by workers would both ease pressures on transfer systems and move economies closer to a desirable level of capital intensity.

A comprehensive analysis by Elmendorf and Sheiner (2017) concludes that changing demography will lead to slower growth in per capita consumption. Except for countries with very low fertility, higher birth rates do not offer a way out. Lee et al. (2014) show that moderately low fertility, a total fertility rate of 1.7 or so, and current mortality rates support the highest levels of sustainable per capita consumption.

THEORETICAL FOUNDATIONS FOR INTERGENERATIONAL TRANSFERS

The elderly depend heavily on intergenerational transfers and, in their absence, many would face lives of insecurity and impoverishment. The elderly are also an important source of intergenerational transfers, supporting their own descendants and, through their taxes, non–family members of younger generations. What explains the large flows of economic resources across generations? Do intergenerational transfers realize their goals? Do they have unintended consequences for better or for worse?

No single, unified theory explains what leads to intergenerational transfers (Arrondel and Masson, 2006). Altruism may motivate both public and private transfers to children (Becker, 1960, 1991; Willis, 1973) and to the elderly (Altonji et al., 1992, 2000; Lindert, 2004). Alternatively, economic flows that appear to be pure transfers may actually be a form of nonmarket exchange. Parents may view children as an investment (Leibenstein, 1972;

Caldwell, 1982) or as a form of insurance (Kotlikoff and Spivak, 1981), with flows from parents to children at one stage of the life cycle balanced by flows from adult children to parents later in life. In his seminal paper on the exchange motive, Cox (1987) hypothesized that transfers from parents to adult children were compensation for care-giving or attention. Adults also may leave bequests out of altruism or in exchange for attention and care-giving from adult children. And because of uncertainty about the age of death, incomplete annuitization, and precautionary saving, a substantial portion of bequests may be accidental.

Research often treats public transfers as exogenous or as a consequence of an essentially mechanical interaction between exogenous policy and changes in age structure. This approach is particularly favored in research on how public policy should respond to population aging (Feldstein and Liebman, 2002; Diamond, 2004; Feldstein, 2006; Elmendorf and Sheiner, 2017). But why public transfers vary across countries and over time is an important and interesting question. Public transfers may be a consequence of altruism, an entirely selfish outcome of self-serving political behavior (Lindert, 2004), or a mechanism for responding to incomplete markets or market failure. Public transfers arise through social insurance schemes that respond to health and long-term care needs, disability, and unexpected longevity, for example.

Influential research by Becker and Murphy (1988) combines altruism, investment motives, and market failure in a theory of intergenerational transfers. Parents care about the present and future well-being of their children, and they allocate their resources accordingly, providing for their children’s current consumption and investing in their human capital to raise their future income. But parents also care about their own current and future consumption. Given their limited resources, many parents may invest less in their children’s human capital than would be optimal, given the interest rate or rate of return to regular capital. In this case, the child might wish to borrow to fund further investment but be thwarted by credit market imperfections. Parents might then step in to loan their children the funds to invest further in their human capital, with the understanding that the children are expected to repay the loan when the parents are old. Then children’s education would be funded partly by altruistic transfers from the parents and partly by a family credit market, or exchange. If adult children assist their parents, this could either reflect altruistic feelings toward them or it could be a repayment of an earlier loan.

If cultural values or institutional mechanisms are not in place to enforce repayment of this kind of parental loan, then children—and society—may be stuck with a lower level of education than would otherwise be desirable and efficient. This situation provides a rationale for introducing a public transfer system in which children receive public education, funded by tax-

ing their parents’ generations, while the adults who were compelled to pay for this education through taxes are themselves repaid through a public pension program, funded by taxing the children’s generation. This is an elegant story about how private and public systems might interact to provide a better outcome, when public transfers improve on what is possible through the family alone.

Samuelson (1958) provided a different theoretical perspective on why public transfer programs may enhance welfare by responding to incomplete markets. He showed that in an economy with no capital or other durable goods, a credit market (intertemporal exchange) could not achieve an efficient pattern of life-cycle consumption. Achieving a desirable consumption trajectory requires saving during the working years to accumulate assets that can then be used to pay for consumption in old-age retirement. But in this model of society, every generation is a creditor, with larger or smaller stocks of assets, and no one is a debtor. In a credit market, however, one person’s credit must be matched by another person’s debt. Credit markets cannot be relied on to meet life-cycle needs. Samuelson showed that the life-cycle problem can be addressed through a social contract under which current elderly receive support from current workers, who receive support when old from the next generation of workers—and so on, forever.

Samuelson’s approach is much like a Pay As You Go public pension system such as the U.S. Social Security system. For such a system, Samuelson showed that the rate of return earned by the contributions of workers, compared to their eventual benefits, would be equal to the rate of growth of aggregate income. This same insight applies equally to a familial system of support for the elderly. This feature of intergenerational transfer systems makes them highly vulnerable to slowing labor force growth and population aging. In a rapidly growing population there are many workers to support each elder, so contributions can be small relative to eventual benefits and the rate of return high. But in a declining population the opposite is true. Enter population aging: with slowing population growth rates and increasing numbers of elderly per worker, transfer programs for the elderly appear to be in trouble.

An alternative to relying on intergenerational transfers is to invest in productive capital, yielding a rate of return determined by markets and the underlying health of the economy. However, the desire to hold assets at each age, aggregated across the population, might be so large—particularly in an aging population—that the rate of return on capital could be driven below the rate of return on transfers (the population growth rate plus the productivity growth rate). In this case it would be efficient to satisfy some of the asset demand through transfer systems to the elderly, reducing asset holdings until their rate of return rises to equal that on transfers. This possibility, that population aging could raise the demand for assets to a point

where interest rates drop toward zero, is one aspect of “secular stagnation” (Summers, 2014), and indeed proposed policies for ameliorating secular stagnation include increasing public transfers to the elderly and raising the retirement age (Teuligs and Baldwin, 2014). Government debt is another form of transfer to the elderly, and raising it has also been proposed.

There are many other ways in which public and private transfers interact with one another and with other aspects of economic behavior. Any transfer system alters economic incentives, influencing labor supply, saving, investment in human capital, and health care usage. In this way, public transfers may reduce economic growth further. Private transfers may be less subject to this side effect than public ones because of altruistic linkages and family monitoring of behavior. Public transfers also alter the private incentives for childbearing. Public pensions may reduce a parental motive to have children to provide old-age support, and the future contributions of children to public pension systems are now a societal benefit that does not accrue to their parents, resulting in lower fertility. In other settings, public provision of education and health care for children may encourage higher fertility.

Yet another possibility is that the government tries to raise the welfare of the elderly by giving them a larger pension, financed by taxing their children’s generations. If the balance between their own consumption and their children’s was already what the parents wanted, then they might offset increased public transfers by making private transfers to their children, as suggested by Barro (1974). This would undermine the public policy and would also effectively raise the cost to parents per child, further distorting the parental fertility incentives (Becker, 1993). This kind of private response would depend on the extent to which the motivation for private transfer behavior is altruistic and keyed to the well-being of each generation. If instead, the observed private flows of funds and care across generations are motivated by exchange, then these flows would not change in response to public policy.

ANATOMY OF THE U.S. GENERATIONAL ECONOMY

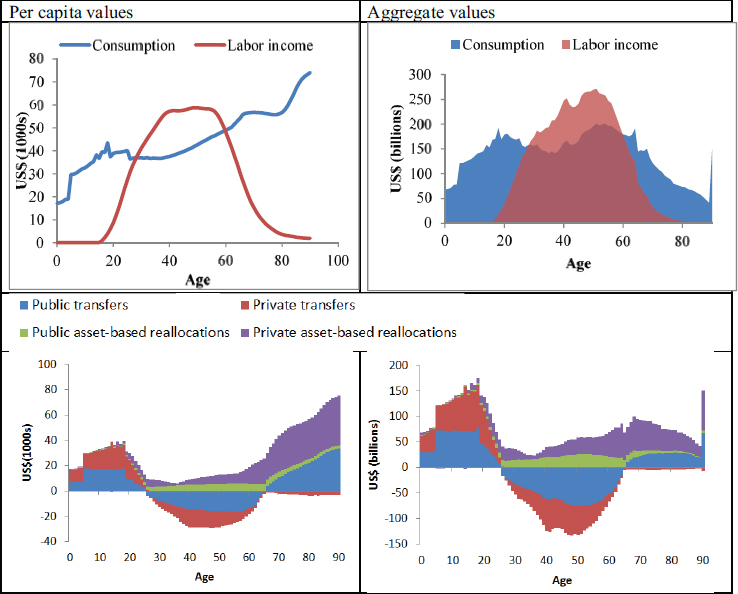

In 2011, Americans produced more through their labor than they consumed for a relatively short age span: from ages 28 to 59 inclusive. Those who were 28 and younger or 60 and older consumed more than they produced through their labor. Labor income was important for older Americans, funding 57 percent of consumption at age 65 and 27 percent at age 70. However, the gap between consumption and labor income was large at older ages. The per capita deficit was $50,000 at age 77 and exceeded $70,000 for those 88 and older. This compares with a peak deficit for children, realized at age 18, of just under $40,000. Spending on health care

was the main reason that the very old in the United States have such a large life-cycle deficit (see Figure 7-1).

The elderly can fund their life-cycle deficit in only two ways. First, they can rely on assets, either the income generated by their assets or by spending down their wealth (borrowing is just another way of spending down their wealth). Second, they can rely on intergenerational transfers from family

NOTES: Per capita values in the left-hand panels are in US$ thousands; aggregate values in the right-hand panels are in US$ billions. Life-cycle variables are in the upper panels; age reallocations are in the lower panels. Consumption includes all private and public consumption classified by the age of individuals, not the age of the household head or some other household marker. Labor income includes all compensation, including benefits, of employees and estimates of the value of labor by the self-employed and unpaid family workers. Both consumption and labor income are adjusted to match aggregate totals based on the U.S. National Income and Product Accounts. All transfers are net values defined as transfers received less transfers given. Asset-based reallocations are equal to asset income less saving.

SOURCE: Data from U.N. Population Division (2013), updated from Lee et al. (2011).

members or other private sources and through public programs such as Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, disability insurance, and so forth.

Young seniors in the United States rely heavily on assets. The asset income they devoted to consumption, and not saving, was about $20,000 per year at age 60. By age 87, asset income devoted to consumption reached $40,000 per year, but it funded a much smaller share of the old-age deficit. Older Americans on average continued to save until their late 80s. They funded old-age consumption by relying on income from assets, but not by dis-saving.

Net transfers (public plus private) to young elderly, those between the ages of 60 and 65, were negative even though they were consuming more than they earned. Only after age 65 did they begin to look to intergenerational transfers as a resource. By age 75, net transfers to the elderly amounted to about $14,000 per year, increasing steadily to reach $30,000 for those 90 and older. At no age in the United States are net transfers to the elderly as large as asset-based reallocations.

However, net private transfers to the elderly are negative at every age. Even those 90 and older are giving about $3,000 more per year—not including bequests—to their children than they are receiving. Thus, the elderly are relying on net public transfers, which rise to $33,400 for those 90 and older.

How do public transfers to seniors compare to transfers to children? Per capita transfers depend on age. Public transfers to preschool children in the United States were between $7,000 and $8,000, and such transfers were between $17,000 and $18,000 for school-age children (ages 5–18). Net public transfers to the elderly were $16,900 at age 75 and $29,300 by age 85. On a per capita basis, then, net public transfers to older seniors exceeded net public transfers to school-age children—more for health than for education.

The aggregate features of the generational economy depend on population age structure in addition to the per capita values. The 0–24-year-old population was about two and half times the 65 and older population in 2011: 101 million versus 41 million. The total U.S. life-cycle deficit for children and the elderly combined was almost $5 trillion in 2011, more than 53 percent of total labor income (see Table 7-1). The child/youth deficit was about 60 percent of the total, while the deficit for older adults was 40 percent of the total. The life-cycle surplus of those between the ages of 25 and 64 was insufficient to fund the deficits of the young and the old. The shortfall was $3.4 trillion, equal to 37 percent of total U.S. labor income (Table 7-1). That portion of the deficit was funded by asset-based reallocations—asset income less saving.

TABLE 7-1 Summary National Transfer Account, United States, 2011

| Life-Cycle Components | Reallocations | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consumption | Labor Income | Life-Cycle Deficit | Net Transfers | Asset-based Reallocations | Total | |||

| Public | Private | Public | Private | |||||

| Per Capita Flows (US$ 1000s) | ||||||||

| 0–24 | 34.1 | 4.0 | 30.1 | 13.4 | 14.1 | 0.7 | 1.9 | 30.1 |

| 25–64 | 40.7 | 49.8 | –9.1 | –12.2 | –8.4 | 4.7 | 6.7 | –9.1 |

| 65+ | 58.7 | 12.0 | 46.7 | 15.9 | –2.6 | 3.8 | 29.6 | 46.7 |

| All ages | 40.8 | 29.7 | 11.0 | –0.2 | –0.3 | 3.3 | 8.2 | 11.0 |

| Aggregate Flows (US$ billions) | ||||||||

| 0–24 | 3433 | 403 | 3030 | 1346 | 1417 | 74 | 193 | 3030 |

| 25–64 | 6842 | 8373 | –1531 | –2055 | –1406 | 797 | 1133 | –1531 |

| 65+ | 2429 | 497 | 1933 | 658 | –108 | 159 | 1224 | 1933 |

| All ages | 12705 | 9273 | 3432 | –52 | –97 | 1030 | 2550 | 3432 |

| Aggregate Flows (percentage of total labor income) | ||||||||

| 0–24 | 37.0 | 4.3 | 32.7 | 14.5 | 15.3 | 0.8 | 2.1 | 32.7 |

| 25–64 | 73.8 | 90.3 | –16.5 | –22.2 | –15.2 | 8.6 | 12.2 | –16.5 |

| 65+ | 26.2 | 5.4 | 20.8 | 7.1 | –1.2 | 1.7 | 13.2 | 20.8 |

| All ages | 137.0 | 100.0 | 37.0 | –0.6 | –1.0 | 11.1 | 27.5 | 37.0 |

NOTES: See Figure 7-1. Aggregate net transfers to the young deficit ages were much larger than aggregate net transfers to old deficit ages. Net transfers to those 0 to 24 years of age totaled $2.8 trillion (30% of total labor income), as compared with net transfers to the old deficit ages totaling only $0.6 trillion (5.9% of total labor income). Net public transfers to these young totaled $1.3 trillion (14.5% of total labor income) as compared with $0.7 trillion (7.1% of total labor income) to the 65 and older group.

COMPARATIVE FINDINGS

Aging is a global phenomenon, with every country in the world except Niger and Equatorial Guinea expected to have an older population in 2020 than in 2015 (UN 2017). However, the extent and pace of aging vary enormously by country, particularly when account is taken of variation across countries in the economic roles of older adults. In countries where the gaps between per capita labor income and per capita consumption are low among seniors, aging will be much less disruptive than in countries where the gaps are large. Moreover, countries vary greatly in the extent to which they rely on intergenerational transfers to fill those gaps. For those that rely heavily on intergenerational transfers, aging will be much more disruptive than in countries where seniors are relying on assets to fund their old-age needs.

Aging from an Economic Perspective: The Old-Age Gap

Many measures of aging, such as the old-age dependency ratio (OADR), rely on a stylized representation of the life cycle that ignores labor income of older adults and ignores the substantial variation in consumption with age. In the analysis presented here, the old-age deficit relative to labor income, denoted “GAP ratio,” is used to capture the resource needs of the elderly, those 65 and older, relative to the resources available from all who work irrespective of their age. The GAP ratio is not a measure of dependency because old-age needs are met by relying on age reallocations: intergenerational transfers and asset-based reallocations. In the simple consumption loan economy of Samuelson, the life-cycle deficit would equal the net transfers required to support older adults. In the simple life-cycle saving economy of Modigliani and colleagues, the life-cycle deficit would equal the flows required to fund old-age needs relying exclusively on assets (asset income and dis-saving; see, for example, Modigliani and Brumberg, 1954).

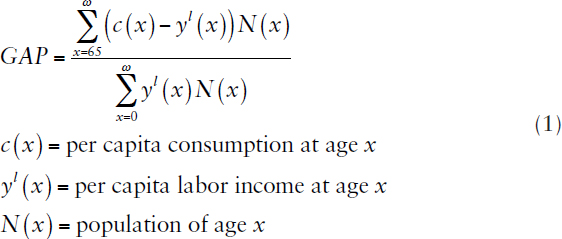

The GAP ratio is calculated as follows:

GAP is constructed using population by age (UN 2017) and per capita consumption and labor income profiles based on NTA estimates available for 119 countries (Mason et al., 2016).

In 2015 the estimated GAP ratio for all countries combined was 11.5 percent of total labor income.3

The GAP ratio is closely related to the OADR. For the sake of illustration, suppose that (a) only those 20 to 64 had labor income and (b) the average consumption of those 65 and older was equal to the average labor income of those 20 to 64. In this instance, the GAP ratio would equal the OADR. In general, neither of these conditions hold because seniors contribute to labor income and seniors consume less than the average labor income of those 20 to 64. Thus, the OADR for 2015 of 16.3 percent was substantially overstated as compared with the GAP ratio of 11.5 percent. From an economic perspective, aging was a less disruptive force in 2015 than implied by the OADR.

The GAP ratio is very small in low-income countries because seniors have relatively high labor income and relatively low consumption. In 2015, the GAP ratio for these countries was only about one-third of the OADR: 3.0 percent as a compared with 8.7 percent. For middle-income countries, the GAP ratio was a little more than half of the OADR. For high-income countries, the GAP ratio was about three-quarters of the OADR: 19.7 percent versus 25.6 percent. From an economic perspective, rather than a purely demographic perspective, aging is an even more severe effect in high-income countries than it is in low-income countries.

Recently, labor income has increased at older ages in many high-income countries. But old-age consumption in the United States has increased even more than labor income, and hence the GAP ratio has continued to rise relative to the OADR.

The life-cycle patterns in high-income countries are reinforcing the effects of aging.

The GAP ratio varies considerably among the high-income countries. In 2 countries, Japan and Greece, the GAP ratio was more than one-third of total labor income; in 16 countries it was less than 20 percent of total labor income (see Figure 7-2). Except for Japan, the highest ratios are found in Europe. Lower GAP ratios are found in the Americas, Australia and New Zealand, and East Asia.

___________________

3 Simple average based on 119 countries.

NOTES: A few small countries have not been included.

Intergenerational Transfers

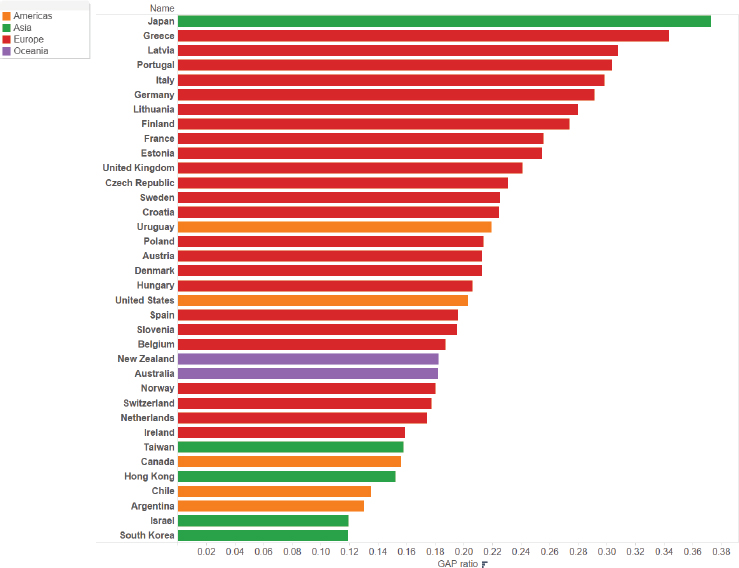

A large GAP ratio represents a high potential demand for intergenerational transfers to seniors. However, as explained above, the old-age deficit may be funded by relying on assets. Moreover, countries may differ considerably in the extent to which they rely on public transfers rather than private, familial-based transfers. Using the most recently available data for 29 countries, we see extraordinary diversity in how countries are currently meeting the needs of their older populations.

Figure 7-3 shows the shares of the life-cycle deficit funded by public transfers, private transfers, and asset-based reallocations, based on the most recent estimate for each country. Before turning to the results, however, a word about interpreting the triangle graph might be helpful. A country located at any of the three vertices is relying exclusively on that source of funding. The Philippines (PH) and India (IN), for example, are relying almost entirely on asset-based reallocations while Hungary (HU) is relying almost exclusively on public transfers. No country in our dataset

NOTES: Country codes and values for the three sources of funding are shown in Table 7-2. Values for Indonesia (not shown): asset-based reallocations are 146 percent of the life-cycle deficit, net public transfers are 2 percent, and net private transfers are 48 percent.

is relying exclusively on private transfers. Countries located along any of the triangle’s sides are relying exclusively on two sources of funding and not a third. For example, net private transfers to the elderly are zero in the United Kingdom (GB); they rely on a combination of public transfers and asset-based reallocations. At the intersection of the “1/3 gridlines” at the center of the triangle, the life-cycle deficit is funded equally from the three potential sources. Only South Korea (KR) and Taiwan (TW) have support systems that are relatively balanced in this way. There are many countries where net private transfers to older adults are negative, in other words the elderly are giving more to their children than they are receiving. Values can be read by extending gridlines beyond the triangle. In Mexico (MX), for example, public transfers are about one-third of the life-cycle

deficit of the elderly. Values and country codes are shown in Table 7-2, which provides estimates of the age reallocations that funded the life-cycle deficit of those 60 and older and 65 and older. The latter estimates were used for Figure 7-3.

The importance of public transfers in the old-age support system varies greatly around the world. The key tradeoff is between asset-based reallocations and net public transfers. In countries where the elderly are relying more on net public transfers to fund their life-cycle deficit, they are relying less on asset-based reallocations. An increase in the public transfer share by one percentage point is associated with a 0.9 percentage point decline in the share funded by asset-based reallocations.

Three groups can be distinguished along the public transfer–asset-based reallocation axis in Figure 7-3. Public transfers dominate in most continental European and Latin American countries. Except for Spain and El Salvador, net public transfers fund at least two-thirds of the life-cycle deficit in this group. In four of these countries—Brazil, Ecuador, Hungary, and Sweden—net public transfers to the elderly exceed the life-cycle deficit.

Public transfers play a significant but more moderate role in East Asia (China, South Korea, Taiwan, and Japan), in Anglo-American countries (Australia, the United States, and the United Kingdom), and in Spain and Mexico. For elderly in these countries, asset-based reallocations also play an important role, funding between one-third and two-thirds of the lifecycle deficit. Mexico, with much heavier reliance on assets and less on the family, and China, with much less reliance on assets and more on family, are exceptions to this generalization.

In a third group, consisting mostly of middle- or low-income countries, the elderly depend heavily on asset-based reallocations and lightly on net public transfers. In most of these countries, the elderly are paying as much in taxes as they are receiving in benefits. Net public transfers are close to zero in Cambodia, India, Indonesia, the Philippines, South Africa, and Thailand.

Net public transfers to the elderly fund 65 percent or more of their life-cycle deficit in 8 of 10 European countries and 6 of 8 countries in Latin America.

Net public transfers fund between one-third and two-thirds of the life-cycle deficit in Anglo-American and East-Asian countries.

Net public transfers to the elderly are very low in lower-income countries—less than one-third of the life-cycle deficit and often close to zero.

TABLE 7-2 Reallocations as a Share of the Life-Cycle Deficit, Ages 60 and Older and 65 and Older

| Country | Code | Year | 60 and Older | 65 and Older | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public Transfers | Private Transfers | Asset-Based Reallocations | Public Transfers | Private Transfers | Asset-Based Reallocations | |||

| Low Transfer Group | 0.01 | –0.24 | 1.23 | 0.05 | –0.07 | 1.02 | ||

| Cambodia | KH | 2009 | 0.06 | 0.22 | 0.71 | 0.06 | 0.22 | 0.72 |

| El Salvador | SV | 2010 | 0.16 | 0.04 | 0.79 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.67 |

| India | IN | 2004 | 0.02 | –0.14 | 1.11 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.95 |

| Indonesia | ID | 2005 | 0.00 | –0.79 | 1.79 | 0.02 | –0.48 | 1.46 |

| Philippines | PH | 1999 | –0.09 | –0.27 | 1.36 | –0.01 | 0.05 | 0.96 |

| South Africa | ZA | 2005 | –0.13 | –0.40 | 1.53 | 0.00 | –0.26 | 1.27 |

| Thailand | TH | 2011 | 0.03 | –0.34 | 1.31 | 0.08 | –0.22 | 1.13 |

| Balanced Group | 0.43 | 0.13 | 0.44 | 0.46 | 0.17 | 0.37 | ||

| China | CN | 2007 | 0.57 | 0.17 | 0.26 | 0.56 | 0.20 | 0.25 |

| Japan | JP | 2004 | 0.52 | –0.03 | 0.51 | 0.57 | 0.01 | 0.42 |

| South Korea | KR | 2000 | 0.36 | 0.08 | 0.56 | 0.36 | 0.21 | 0.43 |

| Taiwan | TW | 2010 | 0.27 | 0.29 | 0.44 | 0.35 | 0.28 | 0.38 |

| Partially Balanced Group | 0.40 | –0.12 | 0.72 | 0.46 | –0.08 | 0.62 | ||

| Australia | AU | 2010 | 0.40 | –0.01 | 0.61 | 0.47 | 0.02 | 0.51 |

| Mexico | MX | 2004 | 0.33 | –0.41 | 1.08 | 0.37 | –0.25 | 0.89 |

| Spain | ES | 2000 | 0.59 | –0.10 | 0.51 | 0.63 | –0.13 | 0.50 |

| United Kingdom | GB | 2007 | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.61 | 0.46 | 0.00 | 0.55 |

| United States | US | 2011 | 0.28 | –0.07 | 0.80 | 0.37 | –0.05 | 0.68 |

| High Public Transfer Group | 0.84 | –0.13 | 0.28 | 0.86 | –0.08 | 0.22 | ||

| Austria | AT | 2010 | 0.85 | 0.00 | 0.15 | 0.89 | –0.01 | 0.12 |

| Brazil | BR | 1996 | 1.06 | –0.52 | 0.46 | 1.08 | –0.38 | 0.30 |

| Costa Rica | CR | 2004 | 0.66 | –0.12 | 0.46 | 0.66 | –0.02 | 0.36 |

| Ecuador | EC | 2011 | 1.18 | –0.16 | –0.02 | 1.14 | 0.00 | –0.13 |

| Finland | FI | 2006 | 0.77 | 0.02 | 0.21 | 0.83 | 0.02 | 0.15 |

| France | FR | 2011 | 0.70 | –0.09 | 0.39 | 0.73 | –0.07 | 0.34 |

| Germany | DE | 2003 | 0.66 | –0.07 | 0.42 | 0.71 | –0.07 | 0.36 |

| Hungary | HU | 2005 | 1.04 | 0.07 | –0.11 | 0.99 | 0.05 | –0.05 |

| Italy | IT | 2008 | 0.75 | –0.06 | 0.30 | 0.81 | –0.05 | 0.24 |

| Peru | PE | 2007 | 0.83 | –0.37 | 0.54 | 0.82 | –0.24 | 0.42 |

| Slovenia | SI | 2010 | 0.70 | 0.04 | 0.26 | 0.72 | 0.04 | 0.24 |

| Sweden | SE | 2006 | 1.08 | –0.20 | 0.11 | 1.08 | –0.13 | 0.06 |

| Uruguay | UY | 2006 | 0.62 | –0.30 | 0.51 | 0.66 | –0.21 | 0.49 |

NOTE: Group values are simple averages of group members.

SOURCES: Data from National Transfer Accounts; see www.ntaccounts.org. Also see Lee and Mason (2011), United Nations Population Division (2013).

Private/familial transfers play a secondary role in the old-age support system. In no case are net private transfers to those 65 and older more than one-third of their life-cycle deficit. To the extent that the elderly do rely on private transfers, region rather than country income appears to play a significant role. The countries with net private transfers to the elderly are found in East and Southeast Asia (Cambodia, China, South Korea, and Taiwan). The exception to this generalization is El Salvador.

In a number of Latin American countries, those 65 and older have net negative private transfers. They are contributing more to their children than they are receiving. In three of the countries, net public transfers to the elderly are very substantial: more than two-thirds of the life-cycle deficit in Uruguay and Peru, and more than the life-cycle deficit in Brazil. So this Latin American pattern may reflect an altruistic response of the elderly to the large public transfers they receive. This behavior is in line with the idea that heads of dynastic families formulate an idea of appropriate income sharing across the generations, and use private transfers to offset government taxes and transfers that distort that distribution (this is one interpretation of “Ricardian equivalence”; see Barro, 1974).

In four other countries, the elderly make relatively large downward transfers to younger generations in the absence of substantial net public transfers: Indonesia, Mexico, South Africa, and Thailand. The situation in Thailand is a very recent phenomenon. In the early 2000s, net public transfers to the elderly were very modest, while net private transfers to the elderly were equal to about one-third of the life-cycle deficit.

For many countries, net private transfers to the elderly are small. This includes Western countries (Australia, Europe, and the United States), some Latin American countries (Costa Rica and Ecuador), and several Asian countries (India, Japan, and Philippines). In Japan and many other countries, net private transfers do vary with age, turning positive for the oldest old.

Only in Asia, with minor exception, do the elderly rely on net private transfers to meet their old-age needs. Even there, net private transfers are less than one-third of the old-age deficit.

In three of the six Latin American countries where net public transfers to the elderly are very large, downward familial transfers are substantial.

The evidence for a tradeoff between public and private transfers is limited. In three Latin America countries (Brazil, Peru, and Uruguay), very substantial net public transfers to the elderly are offset by substantial downward transfers. Likewise, in four Asian countries (Cambodia, China, South Korea, and Taiwan), lower public transfers are accompanied by higher

private transfers, suggesting the possibility of a tradeoff between the two. However, in many countries at varying levels of economic development and in different regions of the world, familial transfers are small, with no apparent connection to public transfers.

FUTURE TRENDS AND POLICY RESPONSES

We cannot be sure how the NTA age profiles will change in the future. In many OECD countries, the age at retirement has been rising over the last two decades, and public pension systems are being reformed in various ways. Meanwhile, cultural values and expectations related to familial support of the elderly are also changing. However, if current age patterns of consumption and labor income were to remain unchanged, population aging over the next 50 years would lead to a very substantial increase in the old-age deficit—particularly, but by no means exclusively, in high-income countries. The first round of effects of higher deficits would be on the old-age support systems comprised of public and private transfers and asset-based reallocations. Given the prevailing nature of old-age support systems, public transfer programs would experience the greatest pressures. This would particularly be true in continental Europe and Latin America, where net public transfers to the elderly as a share of total labor income are projected to double from already high levels. In another important group of aging societies, Anglo-American countries and East Asian countries, net public transfers would increase substantially but would not approach the levels found in Europe and Latin America.

In principle, private transfer systems could come under the same kind of pressure as public transfer systems. But only in East Asia do we see a substantial increase in net private transfers to the elderly. Even there, net public transfers are projected to be more than twice as important as net private transfers over the coming decades. However, it should be kept in mind that the public transfer burden is shared across all taxpayers, whereas the private transfer burden is not and may be quite substantial for those who have surviving, needy aging parents.

Aging has very little projected effect on asset-based reallocations in European and Latin American countries because they currently depend so little on assets to fund their retirement. In other countries—Anglo-American countries and East Asian countries—aging would lead to a substantial increase in asset-based reallocations.

Old-Age Deficit

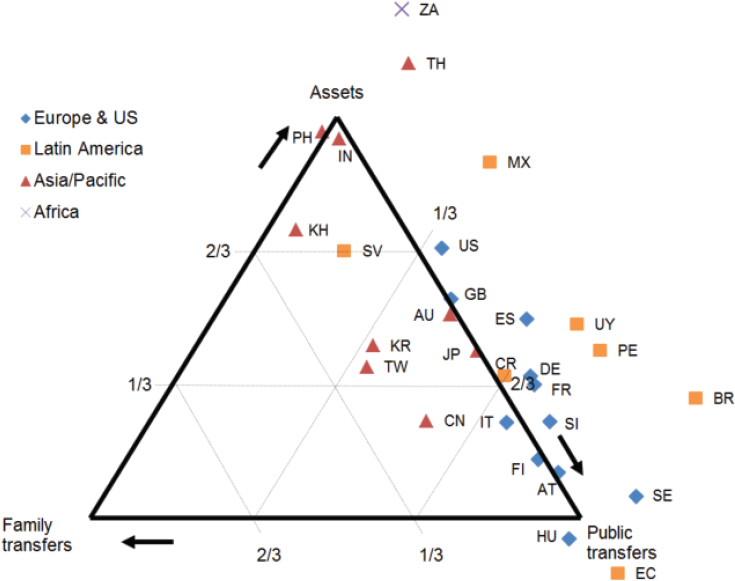

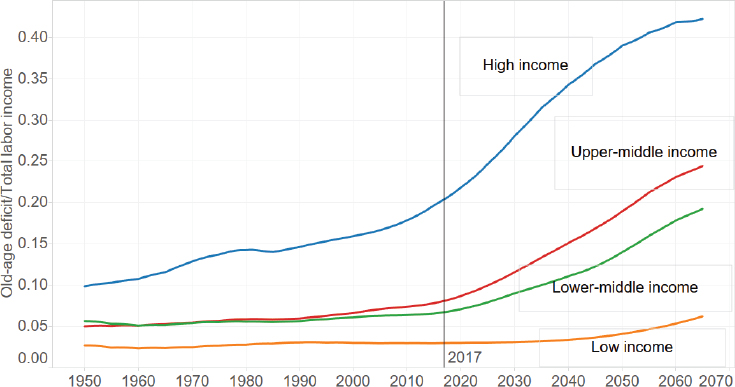

Aging will be quite substantial, as measured by the projected GAP ratio, over the next 50 years in both high- and medium-income countries

(see Figure 7-4). The GAP ratio is projected to rise in high-income countries from about 20 percent of total labor income in 2017 to 42 percent in 2065. The pace of aging is particularly rapid during the next two decades. The average GAP ratio is lower in upper-middle-income countries, but the increase is very substantial, rising from 8 percent of total labor income in 2017 to 24 percent in 2065. The change is similar in the lower-middle-income countries, but we see no increase for several decades in the low-income country group. The GAP ratio there is under 4 percent until 2049 and then rises slowly to reach 6 percent of total labor income in 2065.

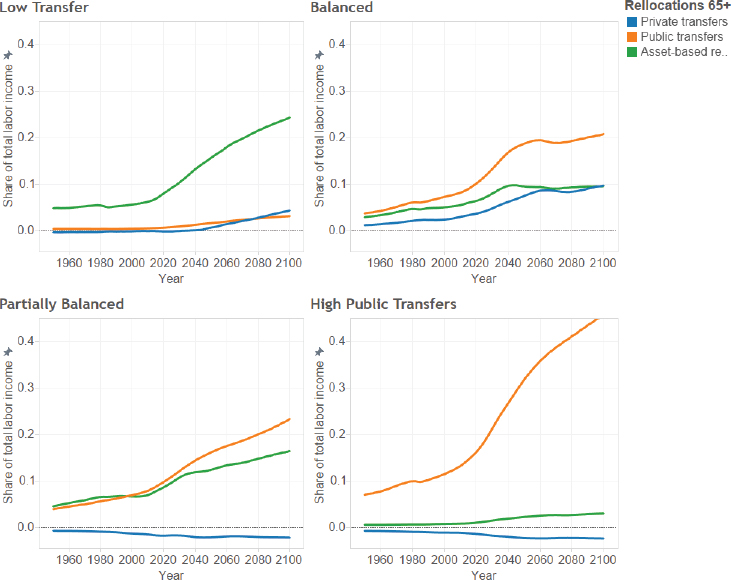

Aging and the Old-Age Support System

The projected trend in public and private transfers to the elderly, along with asset-based reallocations, depends on the extent of aging as captured by the GAP ratio and the support system that prevails in each country. As shown in Figure 7-3, above, the most important variation across countries is in the extent to which they rely on public transfers versus asset-based reallocations. The projections distinguish four groups: (1) countries, mostly low-income countries, that rely lightly on intergenerational transfers and heavily on asset-based reallocations; (2) countries, mostly East Asian, relying on a full complement of mechanisms: public transfers, asset-based

NOTES: Countries are classified based on income group in 2016, using the World Bank classification scheme.

SOURCE: Based on medium variant population projection from UN 2017 and fixed NTA age profiles of consumption and labor income for 188 countries.

reallocations, and family transfers; (3) countries, mostly Anglo-American, with a more balanced reliance on public transfers and asset-based reallocations but little reliance on private transfers; and (4) countries, mostly in the Caribbean, Europe, and Latin America, that rely heavily on public transfers (see Figure 7-5).

For the low-transfer countries, aging has had little impact in the past and only asset-based reallocations are projected to increase in the future, rising from roughly 5 percent of total labor income currently to 20 percent

NOTES: Low-transfer group consists of Cambodia, El Salvador, India, Indonesia, Philippines, South Africa, and Thailand. Balanced group consists of China, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. Partially balanced group consists of Australia, Mexico, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States. High-public-transfers group consists of Austria, Brazil, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Peru, Slovenia, Sweden, and Uruguay.

SOURCE: Calculations (by the authors) use the medium variant of the population projections from UN 2017 and NTA age profiles of public transfers, private transfers, and asset-based reallocations.

of total labor income in 2065. The share of asset-based reallocations is substantially higher than in other country groups, even though the extent of aging is much less in the low-transfer countries.

The balanced country group is projected to experience a substantial increase in net public transfers to those 65 and older, with public transfers as a share of total labor income increasing from about 5 percent in 1950 to over 20 percent in 2065. A distinctive feature of the balanced group is that private transfers rise substantially between now, at 1.6 percent of total labor income, and 2065, at 9.1 percent of total labor income. This occurs because the oldest old are much more dependent on familial transfers than the youngest old. Asset-based reallocations also increase in their importance in the balanced countries but do not quite reach 10 percent of total labor income in 2065.

The projected trends in public transfers and asset-based reallocations in the partially balanced group are similar to the trends for the balanced group, although by 2065 public transfers are lower by about 3 percentage points and asset-based reallocations higher by about 5 percentage points in the partially balanced group. Private transfers to the elderly remain negative throughout the projection period but trend slightly downward.

For the high-public-transfer countries, net public transfers to the elderly are projected to increase sharply, doubling from 19 percent of total labor income in 2017 to 39 percent of total labor income in 2065. For this country group, the projected increase in asset-based reallocations is small, rising from 1.8 to 3.0 percent of total income between 2017 and 2065. Net private transfers are projected to remain negative, trending downward in a fashion very similar to that found in the partially balanced group.

Fiscal Effects and Public Policy

If current age-specific benefit levels were to continue, public spending on old-age needs would grow quite rapidly, particularly over the next few decades, in both high- and middle-income countries. The share of national income devoted to old-age transfers in many European and Latin American countries would reach especially high levels. These undeniable realities have led to a broad consensus that current programs are not sustainable and that public-sector reform is critical (De Nardi et al., 1999; Feldstein, 2006). Adding further to the difficulties is the precarious state of public finances in many countries owing, in part, to the 2008 financial crisis (Holzmann, 2014).

The severity of a coming fiscal crisis will depend in large part on the overall health of the economy under the influence of aging, slowing labor force growth, and other factors that are not heavily influenced by demographic change (National Research Council, 2012). The specter of secular

stagnation represents a pessimistic perspective on long-term prospects, but there is considerable disagreement on key issues (Keynes, 1937; Hansen, 1939; Gordon, 2015; Summers, 2015; Ito, 2016). The impact of age structure on job growth could be offset to some extent by expansive macroeconomic policy leading to higher job growth, higher female participation, and greater participation among young and old workers. Productivity gains, including those attributable to greater human capital investment, could offset the decline in the number of workers. These factors could boost revenue growth and support a larger public-sector role in the old-age support system. Trends in interest rates will have a more mixed impact. Low interest rates, if they continue, will benefit governments with high public debt but will hurt seniors expected to fund a larger share of their old-age needs relying on pensions and other private assets (National Research Council, 2012).

The economic hallmarks of aging at the individual level are the sharp decline in labor income and the rise in health care spending. These features of the life cycle figure prominently in policy formulations directed at curtailing the growth of public transfers to the elderly. A source of optimism is that improvements in health will alter the life cycle by reducing growth in health care spending and facilitating a longer work life (Milligan and Wise, 2012; Coile et al., 2017). This gives rise to two important issues. The first is that improvements in health status are far from certain. In the United States, for example, gains in health status appear to have stalled in recent years and the obesity epidemic raises alarms about the future (Martin et al., 2010; Freedman et al., 2013; see also the chapter by V. Freedman in this volume).

Second, history suggests that improvements in health status cannot be counted on to produce marked changes in the life cycle in the absence of effective policy. Recently, age at retirement in the United States and many other OECD countries has trended upward (see the article by C. Coile in this volume). Before this recent reversal, however, the retirement age was trending downward for a long period (Costa, 1998; De Nardi et al., 1999) and health care spending trended upward (European Policy Committee and European Commission, 2006; Feldstein, 2006; Ogawa et al., 2007), despite steady declines in mortality rates and improvements in health.

The way forward is clearest on the labor side. Improvements in health mean that people can work longer. If older workers remain in the labor force, evidence strongly suggests that young workers will not be adversely affected. Relatively straightforward policies, raising or eliminating the retirement age and reducing the incentives for early retirement created by high effective tax on labor income for older workers, will be effective (Gruber and Wise, 1999).

Health reform is exceedingly complex and contentious and cannot be addressed in any detail here.

Four important considerations are critical in efforts to moderate the growth of public transfers to the elderly. First, public transfers have profound distributional effects. They have helped to reduce poverty among the elderly, overall and relative to other age groups. However, public pension programs in the United States and possibly other countries are regressive because low-income individuals have much shorter life spans (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2015). Second, public programs play an essential role in mediating the high risks faced by the elderly. Market-based alternatives such as lifetime annuities and long-term care insurance have not been adequate alternatives to public programs. Third, many individuals are not prepared to shoulder greater responsibility for the complex challenges of providing for old-age needs (Mitchell and Moore, 1998; Scholz et al., 2006). Finally, political uncertainty in some countries damages efforts by individuals and firms to play an essential role in meeting old-age needs.

Future Needs

In the past, analysis of the linkages between demographic changes and the macroeconomy has been constrained by a gap in national statistical systems. Demographic data are organized around the individual, whereas national accounts are organized around firms, households, and governments. This mismatch between demographic and economic data undermines efforts to analyze the economic effects of the most important demographic changes occurring in countries at all levels of development and at different stages of the demographic transition. Some of the most basic economic data about the elderly are not available.

National Transfer Accounts, used extensively in this paper, were developed to improve the linkages between demographic and macroeconomic data. The value of this approach is demonstrated by the widespread interest in constructing NTA. Currently, NTA are being constructed for more than 90 countries.

The construction of NTA is being carried out by country teams based in universities, think tanks, or government agencies, with coordination provided by an informal network supported through competitive research grants. However, the construction and dissemination of national statistical information is properly the responsibility of national and regional statistical agencies. Some national statistical agencies are exploring the possibility of incorporating NTA into their national statistical systems. Several U.N. agencies, notably the U.N. Population Fund, the U.N. Population Division, and the U.N. Development Program, have been actively involved in the development and dissemination of NTA. However, it is essential that the construction of NTA be incorporated into official statistical systems

at the national, regional, or global level to ensure that this important source of information is broadly available on an ongoing basis.

CONCLUSIONS

Intergenerational transfer systems are critical to the functioning of all societies. They channel resources to children, providing for their material needs and, with a lag, influencing their productivity as adults. And they channel resources to the elderly, with profound implications for their health, their economic security, and other essential features of their lives.

As population aging occurs, old-age intergenerational transfer systems will become both more important and more difficult to sustain. Aging, however, is not a one-size-fits-all problem. Many countries in East and Southeast Asia and Southern and Eastern Europe can expect very rapid aging due to their low rates of fertility. Many countries in Europe and Latin America will face much greater imbalances in their old-age support systems because those public systems are so large. Elsewhere in the world, the United States included, aging is expected to be more moderate with more slowly shifting intergenerational transfer systems.

Public transfers are much more important to the elderly than familial transfers except in a few countries, mostly in East Asia. Consequently it is usually the public transfer systems that are particularly vulnerable to population aging. Even outside Europe and Latin America, the share of national resources needed to support old-age systems would grow substantially in the absence of significant reform.

A critical issue is whether aging will lead to economic stagnation. There is widespread agreement that demographic change will represent a significant headwind for high-income economies for some time. Slower growth of the working-age population will almost surely translate into slower growth in gross domestic product (GDP). It is possible, of course, that other factors could outweigh demographic ones. The impact of aging on per capita income and per capita consumption, in particular, is less certain because of the effects of population aging on human and physical capital accumulation.

The policy responses are likely to prove critical. Labor market and pension reforms are particularly appealing. If people have longer, healthier lives, they can surely work longer. And if people delay retirement, tax revenues can rise and spending on public pensions can be curtailed. Policy with regard to health care is also critical, particularly in the United States where health spending is such a high share of GDP and health policy is in such disarray.

It seems unlikely that private transfers will play a much greater role in the future, given their limited role today. Moving to a sustainable old-age

support system will unquestionably require great reliance on other sources of support besides public or private transfers, notably increased labor at older ages and increased reliance by the elderly on asset income. Funded pensions and other forms of assets are likely to become increasingly important. Such a shift could have favorable growth effects by increasing capital accumulation and reducing tax rates, but it could also lead to other serious challenges, including declining rates of return, increased exposure to new sets of risks, and ignorance and vulnerability on the part of many elderly.

REFERENCES

Altonji, J.G., Hayashi, F., and Kotlikoff, L. (1992). Is the extended family altruistically linked? Direct evidence using micro data. American Economic Review, 82(5), 1177–1198.

Altonji, J.G., Hayashi F., and Kotlikoff, L. (2000). The effects of income and wealth on time and money transfers between parents and children. In A. Mason and G.Tapinos (Eds.), Sharing the Wealth: Demographic Change and Economic Transfers between Generations (pp. 306–357). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Arrondel, L., and Masson, A. (2006). Altruism, exchange or indirect reciprocity: What do the data on family transfers show? In S.-C. Kolm and J. M. Ythier (Eds.), Handbook of the Economics of Giving, Altruism, and Reciprocity (vol. 2, pp. 971–1053). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Barro, R.J. (1974). Are government bonds net worth? Journal of Political Economy, 82(6), 1095–1117.

Becker, G. (1960). An economic analysis of fertility. In National Bureau of Economic Research, Demographic and Economic Change in Developed Countries (pp. 209–240). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Becker, G. (1991). A Treatise on the Family (enlarged edition). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Becker, G. (1993). Nobel lecture: The economic way of looking at behavior. Journal of Political Economy, 101(3), 385–403.

Becker, G.S., and Barro, R.J. (1988). A reformulation of the economic theory of fertility. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 103(1), 1–25.

Becker, G.S., and Murphy, K.M. (1988). The family and the state. Journal of Law & Economics, 31(April), 1–18.

Caldwell, J. (1982). The wealth flows theory of fertility decline. In C. Hohn and R. Mackensen (Eds.), Determinants of Fertility Trends: Theories Re-examined (pp. 169–188). Liege, Belgium: Ordina Editions.

Coile, C.C., Milligan, K.S., and Wise, D.A. (2017). Introduction. In D.A. Wise (Ed.), The Capacity to Work at Older Ages (pp. 1–33). Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

Costa, D.L. (1998). The Evolution of Retirement: An American Economic History, 1880–1990. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Cox, D. (1987). Motives for private income transfers. Journal of Political Economy, 95, 508–546.

Cutler, D.M., Poterba, J.M., Sheiner, L.M., and Summers, L.H. (1990). An aging society: Opportunity or challenge? Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1990(1), 1–56.

De Nardi, M., Imrohoroglu, S., and Sargent, T.J. (1999). Projected U.S. demographics and Social Security. Review of Economic Dynamics, 2(3), 575–615.

Diamond, P. (2004). Social Security. American Economic Review, 94(1), 1–24.

Elmendorf, D.W., and Sheiner, L.M. (2017). Federal budget policy with an aging population and persistently low interest rates. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(3), 175–194.

European Policy Committee and European Commission. (2006). The Impact of Ageing on Public Expenditure: Projections for the EU25 Member States on Pensions, Health Care, Long-Term Care, Education and Unemployment Transfers (2004-2050). Brussels: European Commission Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs.

Feldstein, M. (2006). The Effects of the Ageing European Population on Economic Growth and Budgets: Implications for Immigration and other Policies (NBER Working Paper 12736). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Feldstein, M., and Liebman, J.B. (2002). Social Security reform. In A. Auerbach and M. Feldstein (Eds.), Handbook of Public Economics (pp. 2245–2324). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Freedman, V.A., Spillman, B.C., Andreski, P.M., Cornman, J.C., Crimmins, E.M., Kramarow, E., Lubitz, J., Martin, L.G., Merkin, S.S., Schoeni, R.F., et al. (2013). Trends in late-life activity limitations in the United States: An update from five national surveys. Demography, 50(2), 661–671.

Gordon, R.J. (2015). Secular stagnation: A supply-side view. American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings, 105(5), 54–59.

Gruber, J., and Wise, D.A. (1999). Social Security and Retirement around the World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hansen, A.H. (1939). Economic progress and declining population growth. American Economic Review, 29(1), 1–15.

Holzmann, R. (2014). Global pension systems. In S. Harper and K. Hamblin (Eds.), International Handbook on Ageing and Public Policy (pp. 87–107). Cheltenham, UK, and Narthampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

Ito, T. (2016). Japanization: Is it Endemic or Epidemic? (NBER Working Paper 21954). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Keynes, J.M. (1937). Some economic consequences of a declining population. Eugenics Review, 29(1), 13–17.

Kotlikoff, L.J., and Spivak, A. (1981). The family as an incomplete annuities market. Journal of Political Economy, 89(2), 372–391.

Lee, R. (2003). Demographic change, welfare, and intergenerational transfers: A global perspective. Genus, 59(3–4), 43–70.

Lee, R., and Mason, A. (Eds. and principal authors). (2011). Population Aging and the Generational Economy: A Global Perspective. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Lee, R., Donehower, G., and Miller, T. (2011). The changing shape of the economic lifecycle in the United States, 1960 to 2003. In R. Lee and A. Mason (Eds.), Population Aging and the Generational Economy: A Global Perspective (pp. 313–326). Cheltenham, UK, and Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

Lee, R., Mason, A., and Members of the NTA Network. (2014). Is low fertility really a problem? Population aging, dependency, and consumption. Science 346(6206): 229–234.

Leibenstein, H. (1972). An interpretation of the economic theory of fertility: Promising path or blind alley? Journal of Economic Literature, 12(2), 457–479.

Lindert, P. (2004). Growing Public: Social Spending and Economic Growth Since the Eighteenth Century. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Martin, L.G., Schoeni, R.F., and Andreski, P.M. (2010). Trends in health of older adults in the United States: Past, present, future. Demography, 47(Supplement), S17–S40.

Mason, A., Lee, R., and Jiang, J.X. (2016). Demographic dividend, human capital, and saving: Take it now or enjoy it later? Journal of the Economics of Ageing, 7, 106–122.

Milligan, K.S., and Wise, D.A. (2012). Introduction and summary. In D.A. Wise (Ed.), Social Security Programs and Retirement Around the World: Historical Trends in Mortality and Health, Emloyment, and Disability Insurance Participation and Reforms (pp. 1–39). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Mitchell, O.S., and Moore, J.F. (1998). Can Americans afford to retire? New evidence on retirement saving adequacy. Journal of Risk and Insurance, 65(3), 371–400.

Modigliani, F., and Brumberg, R. (1954). Utility analysis and the consumption function: An interpretation of cross-section data. In K.K. Kurihara (Ed.), Post-Keynesian Economics. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2015). The Growing Gap in Life Expectancy by Income: Implications for Federal Programs and Policy Responses: Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/19015.

National Research Council. (2012). Aging and the Macroeconomy: Longer-term Implications of an Older Population. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Ogawa, N., Mason, A., Maliki, Matsakura, R., and Nemoto K. (2007). Population aging and health care spending in Japan: Public and private sector responses. In R. Clark, A. Mason, and N. Ogawa (Eds.), Population Aging, Intergenerational Transfers and the Macroeconomy (pp. 192–223). Cheltenham, UK: Elgar Press.

Samuelson, P. (1958). An exact consumption loan model of interest with or without the social contrivance of money. Journal of Political Economy, 66, 467–482.

Sanderson, W., and Scherbov, S. (2010). Remeasuring aging. Science, 329, 1287–1288.

Scholz, J.K., Seshadri, A., and Khitatrakun, S. (2006). Are Americans Saving “optimally” for retirement? Journal of Political Economy, 144(4), 607–643.

Summers, L.H. (2014). Reflections on the “new secular stagnation hypothesis.” In C. Teuligs and R. Baldwin (Eds.), Secular Stagnation: Facts, Causes and Cures (pp. 60–65). London: Centre for Economic Policy Research.

Summers, L.H. (2015). Demand side secular stagnation. American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings, 105(5), 60–65.

Teuligs, C., and Baldwin, R. (Eds.). (2014). Secular Stagnation: Facts, Causes and Cure. London: Centre for Economic Policy Research.

United Nations Population Division. (2013). National Transfer Accounts Manual: Measuring and Analysing the Generational Economy. New York: United Nations.

United Nations Population Division. (2017). World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision. New York: United Nations.

Willis, R.J. (1973). A new approcah to the economic theory of fertility behavior. Journal of Political Economy, 81(2 Part 2), S14–S64.