4

Social Well-Being and Health in the Older Population: Moving beyond Social Relationships

INTRODUCTION

In 1947, the World Health Organization (WHO) defined health as “. . . a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (Glenn and Weaver, 1979). In 1977, psychiatrist George Engel built on this definition, calling for a new, biopsychosocial model (Engel, 1977). It integrated traditional medicine with psychosocial factors, which stimulated the field of psychosomatic medicine. Since then others have called for conceptualizations of health expanded to include positive health (Ryff and Singer, 1988) or successful aging (Rowe and Kahn, 1997), although these more inclusive definitions have rarely been applied to understanding the health of individuals or populations.

This chapter addresses the theoretical and conceptual underpinnings of various definitions of “social health.” It presents commonly used measures of social well-being, rarely referred to as social health, and briefly reviews the relationship between these measures and other dimensions of health. It suggests ways that assessments of the health of individuals, groups, or populations could be expanded to include social health, and it discusses future directions for research on the demography of social well-being at older ages. Although the WHO definition of health, promulgated over half a century ago, includes social health as equal in importance to physical and psychological health, and some researchers have incorporated the social in

___________________

1 University of Chicago and NORC.

their conceptual frameworks (e.g., Rowe and Kahn, 1997; Ryff and Singer, 1988), it has rarely been incorporated analytically in describing population health or in causal models of population health. Addressing this lack is an important future direction for the demography of aging, but it means that reviews of recent research have little to say on social well-being as a component of health and much more to say on social factors as causes of other dimensions of health. That lack shapes the discussion below on our understanding of the links between social well-being and health.

When WHO added “social well-being” to its definition of health, what did it have in mind? No generally accepted definition of social wellbeing exists. Obviously, it should include adequate and well-functioning social relationships, adequate social support, little or no social strain, some social participation, social inclusion in one’s society, strong and well-functioning social networks, and, perhaps, sexuality as one desires. Some definitions might include more dimensions or types of social behaviors or activities, but we can start here. We begin with theoretical and conceptual approaches to social well-being as a component of health.

THEORETICAL AND CONCEPTUAL APPROACHES TO SOCIAL WELL-BEING AS A COMPONENT OF HEALTH

The standard Medical Model of Health, sometimes called the biomedical model, had its origins in the 1910 Flexner Report (Flexner, 1910), which codified medical education through a focus on diseases, specifically their pathology, biochemistry, and physiology (Stevens, 1971; Starr, 1982; Beck, 2004; Annandale, 2014). In this model, health is the absence of disease, dysfunction, or injury. Engel’s (1977) biopsychosocial model integrated traditional medicine with psychosocial factors, which stimulated the field of psychosomatic medicine.

A focus on physical health and the avoidance of disease defined “successful aging” as conceptualized by Jack Rowe, a physician, and Robert Kahn, a psychologist. Successful aging was distinguished from normal aging, which might include health declines and chronic disease (Rowe and Kahn, 1997). Rowe (1990) defined “staying healthy” as not diseased, not disabled, with a hallmark of successful aging being a low risk of developing chronic disease. Later, Rowe and Kahn (1997) expanded the definition of success to include a low probability of disease and disease-related disability, high cognitive and physical functional capacity, and active engagement with life; one ages successfully if one achieves all three of these goals. No mention is made of good mental health. Subsequent research showed that very few people are able to maintain the high levels of functioning required to be classified as “successful” (Martin et al., 2015). Note that this definition of health includes one measure that may reflect social well-being: active

engagement with life, defined as maintenance of personal relationships and engagement in paid or unpaid activities that produce goods or services of economic value (Rowe and Kahn, 1997).

The related ideas of “positive health” and “successful aging” incorporate the presence or absence of disease, cognitive and functional capacity (Ryff and Singer, 1998), and active engagement with life (Rowe and Kahn, 1997, 1998). Ryff and Singer (1998) pointed to the importance of both mind and body in positive health and focused on the effect of each on the other, but they ignored the social. Rowe and Kahn (1997) privileged cognitive function and ignored psychological well-being. Recent work has moved little beyond this point. Lowsky et al. (2014) defined “healthy aging,” using self-reported health, as getting no help with activities of daily living or instrumental activities of daily living, having no work limitations due to health, not having been diagnosed with any major chronic disease, and having a perfect score on the health-related quality-of-life scale.

Recent research has focused on markers of physiological aging in young adults (Belsky et al., 2015), including physical functioning, cognitive function, and appearance. Social functioning is not included. And a sizable body of research has focused on the effect of social relationships on longevity (Yang et al., 2013, 2016), and the biological mechanisms through which these occur (Yang et al., 2013). These models are based on the assumption that social relationships affect health. But WHO includes social well-being as a component of health.

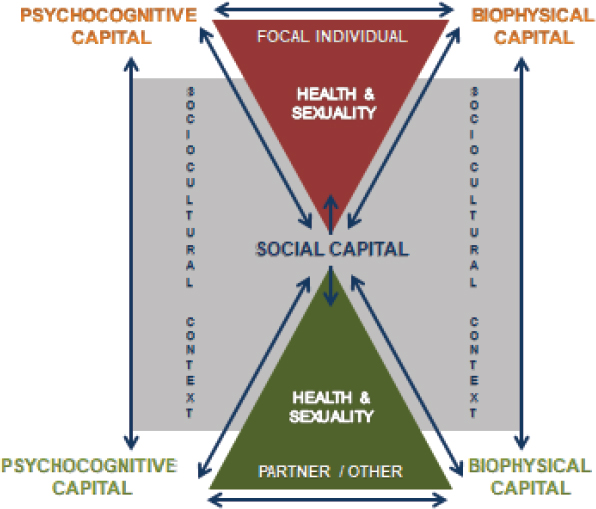

Lindau et al. (2003) proposed an “interactive biopsychosocial model” in which three components, the psychocognitive, biophysical, and social health of each social partner, affect and are affected by each other within a social environment (see Figure 4-1).

Theories Linking Social Well-being to Health

It is generally accepted that the social world “gets under the skin” to affect physical, functional, psychological, and cognitive health and that each of these other dimensions of health affects social well-being. The mechanisms by which this takes place are the focus of various theories linking social well-being to other domains of health. We outline here some of the most well known, beginning with Stress Process Theory (Thoits, 2011; Pearlin et al., 2005). This theory focuses on the body’s physiological responses to stress, which is defined as demands on an organism that it may not have the resources to meet. For humans, this means demands that the person feels that she or he may not have the resources to meet. Stress leads to the stress response—activation of the hippocampal-pituitary-adrenal axis, with resultant increases in blood pressure and heart rate, dumping of cortisol into the blood stream, and increased vigilance. Robert Sapolsky

SOURCE: Lindau et al. (2003). Reprinted with permission of the Johns Hopkins University Press. From Lindau, S.T., Laumann, E.O., Levinson, W., and Waite, L.J. (2003). Synthesis of scientific disciplines in pursuit of health: The Interactive Biopyschosocial Model. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 46(3 Suppl), S74-S86. Permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

(2004) has detailed the various and manifold consequences of stress and the stress response in such works as Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers.

For modern humans, stress is more often social or psychological than physical, given the nature of our lives, but social stress causes the same physiological responses, which can cause wear and tear on the body over time, leading to hypertension, cardiovascular disease, impaired immune function, and even stress-related eating and weight gain. Social relationships, if supportive, can reduce exposure to stress, mute the response to stress, and speed recovery from stress (Thoits, 2011), thereby improving health. Of course, social relationships can also be a source of stress if they are negative, demanding, difficult, or draining (Offer and Fischer, 2017).

Loneliness and Social Isolation

Loneliness and social isolation, important indicators of social health, are related, often confused with each other, but not the same thing. They are siblings rather than identical twins. Loneliness is the subjective assessment that one’s social relationships are lacking, perhaps profoundly so. Lonely people feel that they lack companionship, don’t have a circle of friends, and often feel left out. Socially isolated people may not have many close connections but may feel just fine about it. Theories of the effects of loneliness and social isolation point to different mechanisms through which each operates to put other dimensions of health at risk. Recent research suggests that loneliness is a factor in evolutionary fitness across the life span (Hawkley and Capitanio, 2015). Lonely people feel left out and isolated, that no one has their back. Thus they tend to surveil their social surrounding for risk and to perceive social threats in ambiguous situations. The constant checking for threats uses up cognitive capacity that could be put to other uses, which may contribute to the increased likelihood of developing Alzheimer’s disease faced by lonely people (Wilson et al., 2007). Loneliness is a major source of stress, which puts chronically lonely people at risk of chronic inflammation, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and stroke. Lonely people sleep more poorly, less often wake up rested, and have more trouble staying asleep. They are at risk for depression, poor executive function, accelerated cognitive decline, and impaired immune function (Hawkley and Capitanio, 2015). Loneliness is a candidate for an indicator of poor social health.

Social isolation works to affect other domains of health through mechanisms other than stress. The socially isolated are more likely than others to live alone, to be unmarried, to have small social networks, to participate in few groups, to have few friends, and to socialize infrequently (York Cornwell and Waite, 2009a). Social isolation may mean few sources of emotional or instrumental support. With fewer resources at their disposal, the socially isolated may face more sources of stress than others and have fewer means to alleviate that stress. Those with relatively little contact with others have fewer sources of information and influence to aid in decision making, potentially affecting health behaviors, health care usage, and socially contagious behaviors such as alcohol use, smoking, diet, exercise, and obesity (Smith and Christakis, 2008; Yang et al., 2013). Steptoe et al. (2013) suggested that social isolation may increase the risk of adverse events during acute illness episodes by reducing the availability of help and care. These authors found that social isolation increases risk of mortality, even when loneliness is taken into account, making both candidates as indicators of poor social health.

Social Capital Theory

Social capital is often thought of as the resources that reside within social relationships, especially networks of relationships, and as the information, influence, and even goods and services that flow through these networks. Theoretical development of this concept began with seminal work by Pierre Bourdieu (1986) and James Coleman (1988), who worked separately and developed different approaches, both highly influential. This work was built upon by Robert Putnam (2000), who tended toward a narrow definition of social capital as the nature and extent of networks and the norms of reciprocity they embody. Social capital, in this formulation, allows people to have expectations of access to resources from others in the network. These resources include instrumental and emotional help, advice, information, connection to those outside the network, surveillance of behavior within the network, and other products of relationships. Social capital resides strictly within relationships between individuals within the group of which they are members. Some network scholars argue, in contrast, that social capital consists of the flows of resources through networks, not the networks themselves (Lin, 2001).

Social capital theories all point to features of the social networks of individuals as sources of resources and by this means as indicators of social well-being. Social networks can have many different characteristics, ranging from their size to their configuration and their composition (Cornwell et al., 2009). We discuss these below in the section on dimensions of social well-being.

KEY DIMENSIONS OF SOCIAL WELL-BEING

The next section looks to theoretical perspectives and the research literature to determine the most important and most commonly assessed dimensions of social well-being. These are described briefly. We then discuss ways to measure each of these dimensions.

Presence and Quality of Social Relationships Including Social Dyads

By social relationships we mean any ongoing connection between two or more people. The most fundamental of these are the parent-child relationship and the intimate partner relationship. Together they comprise the family, the foundational social institution in human society (Coontz, 2008; Waite, 2005). The consequences of strong and positive bonds between parents and children have widely recognized consequences for the physical, psychological, cognitive, and financial well-being of both generations across the life course (Maccoby, 1980). Finding and keeping a mate in an

intimate partnership is one of the key developmental tasks of adulthood (Kaufman, 2018), and a successful partnership, some argue, leads to better health of both members of the dyad across all dimensions of health (Waite and Gallagher, 2000). So we list happy childhood as a candidate measure of social health, along with being married or partnered. We might want to specify that a marriage or partnership must be of at least decent quality to count as an indicator of good social health. A poor-quality marriage or partnership, or none at all, would go in the negative social-health column of our measure.

Other social relationships we should consider include family, friends, colleagues, and other types of connections. These relationships serve different roles at various stages of the life course, and one need not have some of each to have good social health. Although there are few older adults who claim to have no friends or who claim to have no family, many have social networks that contain no or few family members and many have networks that contain no or few friends (Litwin and Shiovitz-Ezra, 2010).

Social Networks

People are connected to others in a variety of ways, from kin relationships to socializing to exchanges. Social networks are created by webs of connections among groups of people, so the social network of an individual includes that person’s connections to others and the connections of those other people to each other (Cornwell et al., 2009). Berkman et al. (2000) developed an elegant conceptual model of the links between macro-level social forces, social networks, psychosocial factors, and pathways to health.

There are many ways to define social networks and many ways to measure them. The National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP) pioneered collection of social network data in older adults by focusing on their discussion networks: the people with whom they talk about things that are important to them.2 The respondent names these people, called “alters,” and then the relationship of each of them to the respondent (called “ego” in network research) is ascertained. Are they related and how? How old are they? Do they live with ego? And does ego talk to them about health? Then the respondent is asked in detail about the connection, if any, between each of the pairs of alters named. Did they know each other? Were they related? How often were they in contact? How close was their relationship? This innovation allows researchers to look closely at the links between all those in the network, including flows of information and affection (Cornwell et al., 2009).

___________________

2Table 4-1 in this chapter lists the measures derived from Waves 1 and 2 of NSHAP, together with the mean value of each measure.

TABLE 4-1 Measures Estimated from Waves 1 and 2 of NSHAP

| NSHAP Measure | Mean (Wave #) |

|---|---|

| 1. PRESENCE/QUALITY OF SOCIAL RELATIONSHIPS | |

| Happy childhood (1-disagree → 6-agree) | 4.49 (W2) |

| (a) Relationship quality | |

| Quality of marriage/relationship (1-unhappy → 7-very happy) | 6.33f/6.35g (W2) |

| Thinking that relationship is going well (1-never → 6-all the time) | 5.01f (W2) |

| Quality of relationship, in general (1-not very close→ 4-extremely close) | 3.59f (W2) |

| Spend time together/separately (1-separate; 2-some together, some separate; 3-together) | 2.34f (W2) |

| Frequency of sleeping in same bed (1-never → 6-all the time) | 4.09f (W2) |

| Number of friends (0-none → 5-twenty or more friends) | 3.41 (W2) |

| Number of children (range: 0–18 children) | 2.77 (W2) |

| Number of grandchildren (range: 0–30 grandchildren) | 4.60 (W2) |

| 2. SOCIAL NETWORKS | |

| Network size (0–5 people) | 3.80c (W2) |

| Proportion living in respondent’s household/coresident (0–1) | 0.20c (W2) |

| Proportion kin (0–1) | 0.66c (W2) |

| Relationship between alters/network density (0–1) | 0.77c (W2) |

| Frequency of contact with alters (1-less than once a year → 8-every day) | 6.76c (W2) |

| Emotional closeness to alters (1- not very close → 4-very close) | 3.09c (W2) |

| Likelihood of discussing health with alters (1-not likely → 3-very likely) | 2.56c (W2) |

| Frequency of contact among alters (0-have never spoken to each other → 9-every day) | 4.13c (W2) |

| Closeness to alters (1-not very close → 4-extremely close) | 3.16a (W1) |

| 3. SOCIAL PARTICIPATION | |

| Attend religious services (0-never → 6-several times/week) | 3.27b (W1) |

| Attend organized groups (1-never → 7-several times a week) | 2.66b (W1) |

| Get together with friends, family (1-never → 7-several times a week) | 4.39b (W1) |

| Socialize with neighbors (1-hardly ever → 5-daily or almost every day) | 1.35b (W1) |

| Volunteer (1-never → 7-several times a week) | 2.20b (W1) |

| NSHAP Measure | Mean (Wave #) |

|---|---|

| 4. SOCIAL ISOLATION/LONELINESS | |

| Felt left out (1-often→ 3-hardly ever/never) | 1.32b (W1) |

| Felt isolated (1-often→ 3-hardly ever/never) | 1.26b (W1) |

| Lacked companionship (1-often→ 3-hardly ever/never) | 1.419b (W1) |

| Social disconnectedness (-0.1.30 → 2.34; low→ high disconnectedness) | -0.02h (W1) |

| Perceived isolation (-0.98 → 3.63; low→ high isolation) | -0.01h (W1) |

| 5. SEXUALITY | |

| (a) Sexual Interest | |

| How often respondent thinks about sex (0-never → 5-several times a day) | 2.06 (W2) |

| How often respondent masturbates (0-never → 9-more than once/day) | 1.47 (W2) |

| Frequency of sex with spouse/partner (1-none → 6-once a day or more) | 2.29f (W2) |

| (b) Sexual Attitudes | |

| Importance of sex in own lives (1-not at all important → 5-extremely important) | 2.44 (W2) |

| Sex necessary for relationship (1-strongly disagree → 4-strongly agree) | 2.98 (W1) |

| Feeling sex life as lacking in quality (1-strongly disagree → 4-strongly agree) | 1.2e (W2) |

| Ability to have sex decreases with age (1-strongly disagree → 4-strongly agree) | 2.92 (W1) |

| Love necessary for sex (1-strongly disagree → 4-strongly agree) | 3.20 (W1) |

| Religious beliefs guided sexual behavior (1-strongly disagree → 4-strongly agree) | 3.00 (W1) |

| Attitude toward marital infidelity (1-aways wrong → 4-not wrong at all) | 1.25 (W1) |

| Attitude toward marital infidelity in case of dementia (1-always wrong → 4-not wrong at all) | 1.60 (W1) |

| Attitude toward marital infidelity in case of long-term illness (1-always wrong → 4-not wrong at all) | 1.61 (W1) |

| Find someone they don’t know attractive (0-never → 5-more than once a day) | 1.7e (W2) |

| Amount of effort put in to make themselves attractive to partner (0-no effort → 4-a great deal of effort) | 2.2e (W2) |

| Amount of effort put in to make themselves attractive to someone they found attractive (0-no effort → 4-a great deal of effort) | 1.3e (W2) |

| How often agree to sex when partner asks (0-never→ 4-always) | 3.35 (W2) |

| NSHAP Measure | Mean (Wave #) |

|---|---|

| How often they had sex in past year compared to how often they preferred to have sex (1-much less often → 5-much more often) | 2.05 (W1) |

| Extent to which they feel their sex life is lacking in quality (0-never → 5 always) | 3.4e (W2) |

| How physically pleasurable they find sex with partner (0-not at all → 4-extremely) | 2.97 (W2) |

| How emotionally satisfying they find sex with partner (0-not at all → 4-extremely) | 3.00 (W2) |

| (c) Sexual/Intimate Activity | |

| Frequency of nonsexual acts before sex (1-much less often than prefer → 5-much more often than prefer) | 2.4e (W2) |

| Frequency of kissing, hugging, touching before vaginal intercourse (1-much less often than prefer → 5-much more often than prefer) | 2.7e (W2) |

| Appeal of being touched lightly (1-not at all appealing→ 4-very appealing) | 3.2e (W2) |

| Appeal of hugging (1-not at all appealing→ 4-very appealing) | 3.4e (W2) |

| Appeal of cuddling (1-not at all appealing→ 4-very appealing) | 3.0e (W2) |

| Appeal of sexual touching (1-not at all appealing→ 4-very appealing) | 2.7e (W2) |

| Frequency of caring touch (hug, cuddle, neck rub, holding hands) from partner (0-never → 6-many times/day) | 3.6e (W2) |

| Frequency of caring touch (hug, cuddle, neck rub, holding hands) from non-partner (0-never → 6-many times/day) | 2.6e (W2) |

| Frequency of touch with pet (0-never → 6-many times/day) | 2.4e (W2) |

| (d) Sexual Functioning & Health (0-no, 1-yes) | |

| Pain during sex | 0.06 (W2) |

| Lack of interest | 0.48 (W2) |

| Lack of pleasure | 0.14 (W2) |

| Anxiety about performance | 0.17 (W2) |

| Early climax | 0.12 (W2) |

| Failure to climax | 0.33 (W2) |

| Erectile dysfunction | 0.43 (W2) |

| Failure to lubricate | 0.26 (W2) |

| Extent to which problems bothered respondent (0-not at all → 4-extremely) | 1.00 (W2) |

| NSHAP Measure | Mean (Wave #) |

|---|---|

| 6. SOCIAL SUPPORT | |

| Opened up to family members (1=often → 3=hardly ever/never) | 1.68b (W1) |

| Relied on family members (1=often → 3=hardly ever/never) | 1.41b (W1) |

| Opened up to friends (1=often → 3=hardly ever/never) | 1.97b (W1) |

| Relied on friends (1=often → 3=hardly ever/never) | 1.68b (W1) |

| Opened up to spouse/partner (1=often → 3=hardly ever/never) | 1.27b (W1) |

| Relied on spouse/partner (1=often → 3=hardly ever/never) | 1.16b (W1) |

| Partner understands the way respondent feels about things (0-never → 3-often) | 2.46 (W3) |

| Partner opens up to respondent if [he/she] needs to talk about [his/her] worries (0-never → 3-often) | 2.40 (W3) |

| Partner relies on respondent for help if [she/he] has a problem (0-never → 3-often) | 2.63 (W3) |

| 7. SOCIAL STRAIN (0-never → 3-often) | |

| Partner makes too many demands | 1.15f (W2) |

| Partner criticizes respondent | 1.25f (W2) |

| Partner gets on respondent’s nerves | 1.42f (W2) |

| Partner lets respondent down when respondent is counting on [him/her]? | 0.75 (W3) |

| Family makes too many demands | 0.883 (W2) |

| Family criticizes respondent | 0.802 (W2) |

| Friends make too many demands | 0.532 (W2) |

| Friends criticize respondent | 0.528 (W2) |

| 8. ELDER MISTREATMENT (0-no, 1-yes) | |

| Anyone too controlling | 0.11 (W1) |

| Anyone insults or puts respondent down | 0.15 (W1) |

| Anyone who takes money or belongings | 0.05 (W1) |

| Anyone who hits, kicks, or throws things at respondent | 0.00 (W1) |

| Family conflict at home since respondent turned 60 | 0.21 (W3) |

| Respondent felt uncomfortable with anyone in family since respondent turned 60 | 0.21 (W3) |

| Respondent felt that nobody wanted them around since respondent turned 60 | 0.08 (W3) |

| Respondent told they gave others too much trouble since respondent turned 60 | 0.05 (W3) |

| NSHAP Measure | Mean (Wave #) |

|---|---|

| Respondent has been afraid of anyone in family since respondent turned 60 | 0.02 (W3) |

| Anyone close to respondent has tried to hurt or harm respondent since respondent turned 60 | 0.02 (W3) |

| Respondent has been made to stay in bed or go to bed by family since respondent turned 60 | 0.02 (W3) |

| Respondent has been called names or put down by someone close since respondent turned 60 | 0.13 (W3) |

| Respondent has been forced to do things respondent didn’t want to do since respondent turned 60 | 0.04 (W3) |

| Respondent has had things taken without their OK since respondent turned 60 | 0.10 (W3) |

| Respondent has had money borrowed without it being paid back since respondent turned 60 | 0.21 (W3) |

| 9. SOCIAL ENVIRONMENT (FI ratings) | |

| (a) Neighborhood Condition | |

| Density (1-buildings far apart → 5-buildings close together) | 3.222d (W2) |

| Neighborhood problems | |

| Litter (1 clean → 5 littered) | 1.587d (W2) |

| Noise (1 quiet → 5 noisy) | 1.655d (W2) |

| Traffic (1 no traffic → 5 heavy traffic) | 1.985d (W2) |

| Odor/polution (1 no smell → 5 strong smell) | 1.319d (W2) |

| Respondent’s building (1 well-kept → 5 needs repairs) | 1.567d (W2) |

| Other buildings (1 well-kept → 5 very poorly kept) | 1.652d (W2) |

| Neighborhood social cohesion (1-strongly agree → 5-strongly disagree) | |

| Area is close-knit | 3.16 (W2) |

| People around here willing to help their neighbors | 3.78 (W2) |

| People in area generally don’t get along with each other | 2.34 (W2) |

| People in area don’t share the same values | 2.79 (W2) |

| People in area can be trusted | 3.70 (W2) |

| Neighborhood social ties (0-never → 4-often) | |

| Frequency of people in area visit each other’s homes | 1.74 (W2) |

| Frequency of people doing favors for each other | 1.93 (W2) |

| Frequency of people ask each other for advice about personal things | 0.92 (W2) |

| NSHAP Measure | Mean (Wave #) |

|---|---|

| Perceived neighborhood danger (1-strongly disagree → 5-strongly agree) | |

| People in area afraid to go out at night | 2.44 (W2) |

| There are places in area where everyone knows “trouble” is expected | 2.33 (W2) |

| Taking a big chance if walk alone in area after dark | 2.35 (W2) |

| (b) Household Conditions | |

| Room temperature (1-cold → 5 hot) | 3.05 (W2) |

| Room lighting (1-dark → 5 light) | 3.57 (W2) |

| Room cleanliness (1-clean→ 5 dirty) | 1.74 (W2) |

| Room tidiness (1-neat → 5 messy) | 1.86 (W2) |

| Room noise (1-quiet → 5 noisy) | 1.38 (W2) |

| Room odor (1-no smell → 5-strong smell) | 1.49 (W2) |

NOTES: The footnotes to the reported mean for a measure give the source for the measure and its mean, calculated from the indicated NSHAP wave (W1 = Wave 1, W2 = Wave 2). Means that are not footnoted are the means for responses to items in the NSHAP questionnaire for the wave indicated (i.e., the “measure” is an item in the questionnaire).

a Cornwell et al. (2009, Tbl. 3).

b York Cornwell and Waite (2009b, Tbl. 1).

c Cornwell et al. (2014, Tbl. 1).

d York Cornwell and Cagney (2014, Tbl. 1).

e Galinsky et al. (2014, Tbl. 2).

f Kim and Waite (2014, Tbl. 1).

g Kim and Waite (2014, Tbl. 2).

h York Cornwell and Waite (2009b, Tbl. 3).

The University of California Social Network Study (Offer and Fischer, 2017) took a different approach, asking each respondent about the people whom she or he was involved with in six spheres of activity, including socializing, confiding in, advice, practical help, emergency help, and providing support. The characteristics of the alter and relationship to ego were also obtained. This is a different type of social network than that based on discussion of important matters and does not obtain information about links between the alters.

Social networks are not cast in stone; they change as the situations of the people in them change. The second wave of NSHAP obtains the social network as described 5 years after the first time the social network was measured for respondents. The Wave 2 social network module asks specifically about losses and additions to the network and reasons for them (Cornwell et al., 2014). Social network characteristics have been linked, for example, to health and the management of chronic illness (York Cornwell

and Waite, 2012), to erectile dysfunction (Cornwell and Laumann, 2011), and to medication use (Goldman and Cornwell, 2015). Network loss over 5 years has been found to be greater for older blacks and those of low socioeconomic status (Cornwell et al., 2014).

The study of social networks is poised to benefit from recent leaps in social connectivity and the technology that supports it and from the availability of data from these platforms. The ubiquity of smartphones also provides opportunities for passive collection of data on contacts and thus on networks.

Social Participation

The social participation dimension of social well-being is generally defined as attending organized groups or gatherings. These gatherings might include religious services or meetings of clubs, exercise groups or bowling leagues, playing on a sports team, singing in a choir, being a member of a book club, or being active in a local political or community organization. All involve participating in an organized group with others. One could participate in social events by getting together with family, going out with friends, or attending a neighborhood potluck. And volunteering in a soup kitchen, as a docent in a museum, or at the information desk in a hospital all involve organized groups of people doing things together. Social participation creates weak links between people, may link participants to sources of support—or provide support to others. It offers opportunities to display and act on shared values and beliefs with others and to spend time with others in useful and/or pleasant activities. Social participation is linked to better sleep among older adults (Chen et al., 2016), to better cognitive function (Bowling et al., 2016; Kotwal et al., 2016), to lower or higher levels of depression, depending on the type of organization in which one participates (Croezen et al., 2015), to health behaviors (Lindström et al., 2001), and to preservation of general competence. Social participation is almost always measured by asking respondents whether they participate in various social activities and if so, how often they participate. This could change with the application of tracking technology such as GPS on smartphone, tracking of movements of individuals using cell phone records, use of social media to track searches, and use of data from cameras or tracking devices in public places. Future research in the demography of aging will almost certainly take advantage of these tracking opportunities.

Social Isolation

The theories on social isolation described above point to the mechanisms linking both perceived social isolation, which psychologists call

loneliness, and objective social isolation to other domains of health. And these links appear to be strong. To summarize briefly, the socially isolated face higher risks than the well-connected of poor sleep, unhealthy behaviors such as alcohol use and smoking, obesity, early cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease, poor mental health including depression, poor self-rated health, and early mortality (Hawkley and Capitanio, 2015; York Cornwell and Waite, 2009a). Being lonely or objectively socially isolated is a source of stress, increases exposure to other stressors, and exacerbates their effects. The socially isolated are cut off from sources of instrumental, emotional, advisory, financial, or other support. They use up attention and executive function worrying about social threats and so have less of these resources for the rest of life. If they get sick, they are less likely than others to have people who will help them. This is a powerful case for the inclusion of assessments of loneliness and objective social isolation in any composite or global measure of social well-being.

Measuring Loneliness

Since loneliness is a feeling—the perception that one’s social relationships are lacking or inadequate—one can measure loneliness by asking people how they feel. Measures range from a single question, included as part of the CES-D scale: “I felt lonely,” asked about the last 2 weeks or the last month (Payne et al., 2014), with responses ranging from “never” to “often.” A short scale, included in the Health and Retirement Study and in NSHAP, asks respondents how often over the past 2 weeks they have experienced feelings such as “I lacked companionship,” “I felt left out,” or “I felt isolated from others” (Hughes et al., 2004). And the longest version of the scale, the UCLA Loneliness Scale, contains 20 items (Russell et al., 1980). About one person in five is lonely at any given time, with about half of current feelings of loneliness due to situational factors such as a recent move, and about half being hereditary (Hawkley and Capitanio, 2015).

Measuring Objective Social Isolation

Since being objectively isolated means having relatively few people around one, a fairly vague concept, there are many ways to measure it. York Cornwell and Waite (2009a) created a factor score from number of friends, characteristics of one’s social network, frequency of getting together with friends, family, neighbors, attending meetings of organized groups, and volunteering. Social isolation has also been measured as living alone, being unmarried/unpartnered, or having infrequent contact with others, small social networks, or perceptions of low social support (Berkman et al., 2000; House et al., 1988; Ertel et al., 2008). McPherson and colleagues

(2006) operationalized social isolation as not having a confidant: someone to talk to about matters that are important to one.

Sexuality

Sexuality is an important component of health and well-being throughout the life course. A 2001 report of the U.S. Surgeon General pointed to sexuality as essential to well-being, with calls to attend to sexual health (Office of the Surgeon General, 2001). But serious research consideration of sexual behavior and attitudes, especially among older adults, is relatively recent. Sexuality can be conceptualized as a component of well-being, as a social indicator, and as a predictor or consequence of other dimensions of health (Galinsky and Waite 2014; Liu et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2016; Waite et al., 2009; Galinsky et al., 2014). Because of the increasing recognition by researchers in the demography of aging of the importance of understanding sexuality, detailed measures of sexual behavior, attitudes, beliefs, functioning, and well-being have been included recently in important national surveys of health, including the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA) and NSHAP, and new measures are appearing in other health surveys, including the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. The inclusion of both partners in some longitudinal surveys of older adults, together with questions on sexuality asked of each individually, have allowed researchers to study the contribution of each partner to the sexuality of the dyad (Waite et al., 2017; Galinsky and Waite, 2014; Kim and Waite, 2014). However, the development of theories of sexuality at older ages has lagged behind descriptions of this dimension of social well-being. We point to this as a fruitful potential future direction in the demography of aging. Sexuality has been linked to self-rated health, especially of the male partner (Lindau et al., 2007), to marital quality in the face of health decline (Galinsky and Waite, 2014), and to perceived subjective well-being (Lee et al., 2016). Sexual problems have been shown to be more likely among those with poor mental health (Laumann et al., 2008).

The study of sexuality at older ages encompasses multiple dimensions. In the section below we concentrate on measures of sexuality primarily because much more work has been done on measurement than on conceptualization. This is an area ripe for attention. These measures include sexual desire or interest, sexual activity or behavior, sexual functioning, and sexual health (Lee et al., 2016). Sexual desire consists of both proceptive and receptive behaviors and feelings; proceptive sexuality leads a person to seek out a sexual partner, whereas receptive sexuality increases willingness to have sex when asked (Galinsky et al., 2014). Sexual interest has been measured by asking a person any or all of the following questions: how often he or she thinks about sex, whether in the recent past he/she has lacked interest in sex

(Schafer et al., 2017), how often he or she masturbates, the importance of sex, sexual activity, and failing to have sex because of lack of interest (Iveniuk and Waite, forthcoming).

Sexual attitudes predict partnered sex and sexual interest; those who think about sex more often and those who rate sex as important or very important in their lives have sex more often (Waite et al., 2017). Respondents in the first wave of NSHAP were asked about their attitudes toward sex and sexuality in general and their attitudes about sex in their current or most recent partnership. They were asked about the importance of sex in their own lives and for maintaining a relationship. They were also asked a series of questions about the circumstances under which they would consider sex between a married person and someone other than their marriage partner. In addition, they were asked about their values toward sex, through the extent of their agreement or disagreement with the following statements: “I would not have sex with someone unless I was in love with them,” “My religious beliefs have shaped and guided my sexual behavior,” and “Satisfactory sexual relations are essential to the maintenance of a relationship.” The ability to have sex decreases as a person grows older (Waite et al., 2009).

Respondents in surveys of older adults have been asked if in the recent past they have found someone they don’t know attractive; for those with partners, the amount of effort they put into making themselves attractive to their spouse or partner (spoiler alert: men say “not much” and women say “quite a bit”); or, for those unmarried or unpartnered, how much effort they put into making themselves attractive to someone they find attractive (men say “quite a bit” and women say “not much”) (Galinsky et al., 2014). These questions were included in Wave 2 of NSHAP. A new set of questions asked people to evaluate the quality of their sex life and their social behavior with their partner. These include questions about how often they agree to have sex when their partner asks them; how often they have had sex in the past year, compared to how often they would have preferred to have sex; the extent to which they feel that their sex life is lacking in quality; and how physically pleasurable and, separately, how emotionally satisfying do they find their (sexual) relationship with their spouse/partner to be?

Sexual activity includes sex with a partner and masturbation. Especially at older ages it is important to define sexual activity with a partner quite broadly, as the activities that couples engage in shift away from vaginal intercourse toward touching, cuddling, and kissing (Waite et al., 2009), and sexual inactivity among those with a partner increases with age (Lindau et al., 2007). Assessment of sexual activity might include the specific activities that the person engaged in the last time he or she had sex, such as sexual touching or oral sex (Waite et al., 2009).

Sexual functioning is generally assessed through a series of questions about whether the person experienced each of a set of symptoms for 3 months or more over the past year. These include pain during sex, lack of interest, lack of pleasure, anxiety about performance, early climax, failure to climax, erectile dysfunction (men), and failure to lubricate (women). Some studies ask the extent to which the problems bothered the person (Waite et al., 2009; Laumann et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2016).

Sexual health at older ages is defined by Lee et al. (2016) based on data from ELSA as continued sexual desire, activity, and functioning and is linked to positive subjective well-being with different patterns of these measures for men and women. Older men who have problems with sexual functioning were more likely to have low subjective well-being, whereas for women sexual desire and the frequency of partnered sexual activities predicted positive subjective well-being.

Social Support

The theoretical perspectives outlined above all include mention of social support as a mechanism or pathway through which social capital, social relationships, or social isolation affect health (Berkman et al., 2000). Social support is, quite broadly, any resource that flows between people. These resources can be exchanged within social dyads, such as between spouses or partners, and within social networks or larger social groups such as communities or neighborhoods. Anything that people can exchange can act as a social support resource, but we think most often of instrumental support (such as help with a home repair or picking something up at the store), emotional support, advice or information, financial support, provision of care (such as when one is sick), moral support in a crisis, and social connections to others (such as when a friend calls her sister, the doctor, to ask if she can be seen today for that odd symptom, as a favor to her). The research evidence to date suggests strongly that it is the perception that one has good social support that reduces stress, rather than the actual receipt of support (Thoits, 2011). This makes sense if we think of stress as the perception that one has inadequate resources for the challenges one faces. Knowing one has support is a resource, like money in the bank. It acts as a resource, even if one doesn’t need to spend it now. Berkman et al. (2000) pointed to health behaviors, such as smoking and exercise; psychological pathways, such as depression and self-efficacy; and physiological pathways, such as allostatic load and immune function, as examples of pathways through which social support affects health and mortality.

Social Strain

We know quite a bit about the presence or absence of social ties but less about their quality. More research has been done, for example, on the impact of being married than on the quality of the marital relationship. This is especially true of the social “bad” or negatives in social well-being, but recent research points to their existence and effects. Strains in social dyads are a source of chronic stress and appear more often in relationships that are obligatory, as in the parent-child or sibling relationships. As people have more ability to shed or avoid relationships with a negative component, such as conflict, criticism, or demands, they do so; as a result, their negative relationships become rarer. Divorce or relationship dissolution can rid people of a poor-quality marriage or romantic partnership (Kalmijn and Monden, 2006), one can avoid a sibling or in-law with whom one doesn’t get along, and friends are generally retained only if they provide greater benefits than costs (Offer and Fischer, 2017). Recent research suggests that mild strain, such as nagging or criticizing, may be a benefit in some close relationships. Warner and Adams (2016) found that for disabled married men, increases in negative marital quality, as indexed by criticism, making too many demands, and getting on one’s nerves, reduced loneliness. These relatively mild negatives in the marriage seem to encourage men to persist in social activities that they might give up without the wife’s pushing. In a study that asks directly about difficult people in social networks, Offer and Fischer (2017) found that these people tend to be in close and obligatory social roles with the alter, particularly women relatives and aging parents. One could measure good social health by the lack of negative relationships or poor social health by their presence.

Caregiver Burden

As people age, they face increasing risks of chronic disease, disability (see the chapter by V. Freedman in this volume), cognitive decline, and death. They also often face these challenges in their spouse or partner. Differences by race in the risk of these outcomes and in the age at which they occur have been documented (Umberson, 2017; also see the chapter by Hummer and Gutin in this volume). Poor health, disability, cognitive decline, and other changes with age increase the chances that an older adult will require help with activities of daily living or that his or her spouse or partner will. Having a life partner is generally the first line of defense against declines in functioning for older adults, with adult children, especially daughters, next in line as caregivers (Oldenkamp et al., 2016). Some caregivers experience stress, strain, and physical and emotional exhaustion as a result of the demands of care-giving for an older adult. This is espe-

cially the case when the caregiver is also old, perhaps with chronic disease or mobility limitations (Oldenkamp et al., 2016). Caregiving may lead to depression, physical stress, and mortality, although results are inconsistent (Fredman et al., 2015). The costs of care-giving for the caregiver may differ by the caregiver’s gender, race, ethnicity, and relationship to the care recipient (Jessup et al., 2015), and so these costs are spread unequally across the population (Umberson, 2017). Changes in family relationships across cohorts now entering older ages may result in changes in risks of needing to provide care for others, widening gaps in the burden of care-giving.

Elder Mistreatment or Abuse

As people advance in age, they may become vulnerable to abuse, mistreatment, or neglect in a way that they were not earlier in life. Poor physical functioning, cognitive decline, social isolation, and the need for assistance that can follow frailty or functional limitations make older adults more dependent, and can strain close relationships, increasing the risk of physical and financial abuse and neglect (Dong et al., 2011a, 2011b). Financial abuse becomes more likely because cognitive declines may result in older adults having difficulty recognizing deception in others (Wong and Waite, 2017). Mistreatment puts older adults at risk of poor emotional health (Luo and Waite, 2011), injuries, and mortality (Dong et al., 2011b). This makes a report of abuse by an older adult a candidate for measuring poor social health.

Social Environment

In the same way that the physical environment affects health, through pollution or safe and pretty places to walk, the social environment can reflect and affect health. As one example, recent research (Cagney et al., 2014) found that older adults who lived in neighborhoods in which the rate of foreclosure was high during the Great Recession were more likely to experience incident depression than those in more stable neighborhoods, regardless of their own financial situation. A relatively new literature has focused on the conditions of the household itself, including the presence of dirt, clutter, smell, poor repair, and noise, which together suggest household disorder (York Cornwell, 2013). This research shows links in both directions between household disorder and health. For example, low-income and African American older adults live in more disordered conditions, as do those with poorer physical and mental health. Risk of living in a messy, dirty, noisy household in poor repair is lower for older adults who have a coresident partner, more nonresidential network ties, and more sources of instrumental support (York Cornwell, 2013). At the same time that house-

hold disorder reflects a lack of social support, over time it leads to more kin-centered networks and more strain within family relationships (York Cornwell, 2016).

Neighborhoods act as part of the local social context in which households and individuals are nested. A healthy neighborhood can be distinguished from one that is less salubrious, with measures of neighborhood characteristics obtained through the perceptions of respondents, observations by field interviewers, and linking to administrative and government data (York Cornwell and Cagney, 2014). Using measures included in Wave 2 of NSHAP, researchers have constructed scales of neighborhood problems, neighborhood social cohesion, neighborhood social ties, and perceived neighborhood danger and assessed their reliability and validity (York Cornwell and Cagney, 2014). This research shows that older women report greater neighborhood cohesion and more neighborhood ties than older men, but women also perceive more neighborhood danger. Black and Hispanic older adults reside in neighborhoods with more problems, lower cohesion, fewer social ties, and greater perceived danger. Neighborhood characteristics also vary across residential densities. Neighborhood problems and perceived danger increase with block-level density, but neighborhood social cohesion and social ties were lowest among residents of moderate-density blocks. Neighborhood characteristics have been linked to health conditions including asthma (Cagney and Browning, 2004), health behaviors such as walking (Mendes de Leon et al., 2009), emotional wellbeing (Cagney et al., 2014), and mortality (Browning et al., 2006).

It has become well established by recent literature that health and mortality vary dramatically across cities and regions and that the link between social and economic characteristics of individuals and households varies as well. Chetty et al. (2016) found, as others have, that life expectancy differs substantially across local areas, with especially dramatic variations for the poorest individuals. These differences were associated with health behaviors such as smoking and with characteristics of local areas such as expenditures. Although it is clear that where one lives has enormous consequences for health and is a candidate for inclusion in a global measure of social health, the most important characteristics of areas and the mechanisms through which they operate are not well understood.

DIFFERENTIALS IN SOCIAL WELL-BEING: GENDER, RACE, ETHNICITY, AND SOCIOECONOMIC STATUS

Describing and understanding differences in various dimensions of social well-being across groups is a key future direction in the demography of aging. How do social networks differ by race and ethnicity, for example? How do various measures of social well-being for men and women diverge

with age? We know that at older ages men are much more likely to be married and thus much more likely to be sexually active than are women the same age (Lindau et al., 2007). Recent work by Umberson (2017) points to shockingly higher rates of death of close family members for blacks than for whites in the United States. Umberson points to the impact on social networks, social support, and successful social relationships that may follow from these losses, but little research addresses this and related issues. Gaps in social well-being may be widening. Raley et al. (2015) pointed to a growing racial and ethnic divide in U.S. marriage patterns, for example. And there is no reason to expect that these gaps are similar by gender, race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. This is an important area for future research in the demography of aging and key to understanding health disparities.

It is more important still to describe and understand differences in the links between various dimensions of social well-being and other components of health, for example by race and gender. Liu and Waite (2014) found that marital quality affected cardiovascular risk for older women but not for older men. And recent work by Uchino et al. (2016) found no link between social support and levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), a measure of systemic inflammation. However, social support moderated the effect of CRP in that Blacks (but not Whites), with higher levels of social support showed lower levels of CRP. And we know virtually nothing about variations in social well-being by socioeconomic status, or about differences in the effects of social well-being on health by education or income. Since it could well be the case that race, gender, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status interact in their effects on the link between social well-being and health, this intersectionality deserves attention in future research in the demography of aging.

HOW DO WE MEASURE SOCIAL WELL-BEING?

Social well-being is an essential component of health, according to WHO, so evaluating it is important. People can be healthy on some dimensions of social health if they perceive them to be good. We could put loneliness in this category; if one feels left out, excluded, or alone, then one is lonely. Relationship quality is similar in this respect; one’s marriage is good if one feels that it is. For these dimensions of social well-being, we can just ask each person for her or his evaluation. For other dimensions of social well-being, researchers ask people to describe their social lives and then create measures from those descriptions. Social participation is evaluated by asking people how often they attend religious services; go to meetings of community groups; participate in organized groups like bowling leagues; and get together with family, friends, or neighbors. Various measures of

social participation can be created from the answers to these questions, depending on the research question being asked. Social isolation is measured, generally, by asking people if they are married or have a romantic partner, who lives in their household, how often they participate in activities with other people, how often they are in contact with family members, and what their social networks are like. If they see lots of people often, they are socially connected. If they see few people infrequently, live alone, and so on, they are socially isolated. Social networks can be measured by asking people about those to whom they are connected. But they could also be measured by counting contacts of some type—for example, social media contacts, cell phone call records, or overlaps in activity space (Browning et al., 2017; Cagney and York Cornwell, 2017).

New technology has introduced “objective” measurement of some social activities, such as sleep and exercise. Fitness trackers fitted to research subjects can measure various components of sleep, including latency, the time it takes to fall asleep, sleep efficiency measured as the amount of time in bed spent in sleep, sleep duration, and sleep disturbances (Lauderdale et al., 2014). These same activity-tracking devices can measure day-time activity, from sedentary to vigorous (Huisingh-Scheetz et al., 2014). Activity trackers in homes can map location of and contact between residents.

Social well-being has long been assessed through vital records, administrative data, and business activity. These sources include Social Security earnings and disability income, employment records, mortality records, Medicare claims data, licenses, and legal proceedings such as those for marriage, adoption, and divorce. Mapping programs allow measurement of features of local areas such as parks and night clubs (Browning et al., 2006). The ability to measure dimensions of social health vastly exceeds existing theoretical perspectives from which to understand their actions and importance.

HOW IS SOCIAL WELL-BEING CONNECTED TO OTHER DIMENSIONS OF HEALTH?

Berkman et al. (2000, p. 843) developed a comprehensive conceptual model of the mechanisms through which social integration affects health in “. . . cascading causal process beginning with the macro-social to psychobiological processes that are dynamically linked together . . . .” Throughout, the authors used “social integration” and “social networks” interchangeably, although I would argue that they are quite distinct dimensions of social well-being.

In this model, the macro-structural forces that affect social integration through social networks include culture, socioeconomic factors, politics, and social change, each with subcomponents. These forces condition the

extent, shape, and nature of social networks, which comprise the mezzo level. Berkman et al. focused on social network structure, such as size, density, and range and on characteristics of network ties, such as frequency of contact and intimacy. Here the authors sneak in a measure that many would consider social participation and not a characteristic of a social network. In fact, this measure is described as “frequency of organization participation (attendance)” (Berkman et al., 2000, Fig. 1, p. 847). Simply expanding the mezzo level to encompass “social capital” makes the model more general and more in line with current thinking.

Berkman and colleagues called the next level of their model “psychosocial mechanisms at the micro level.” These mechanisms include social support, social influence, social engagement, person-to-person contact, and access to resources and material goods, all of which affect health through health behaviors and through psychological and physiological pathways.

To summarize this elegant model briefly, and to extend and expand it, social well-being affects and is affected by other dimensions of health through access to resources, such as time, advice, care-giving, housing, expertise, and money (York Cornwell and Waite, 2012); through emotional support (Warner and Kelley-Moore, 2012; Warner and Adams, 2016); through stress reduction and management (Thoits, 2011); through shared social environments such as shared social networks (Cornwell, 2012), households (Schafer et al., 2017), and neighborhoods; through physiological processes (Sbarra, 2009) that lead to chronic disease (Liu and Waite, 2014; Liu et al., 2016; Das, 2013); through physiological processes that lead to social outcomes (Das, 2017); through gender display, power, and status (Cornwell and Laumann, 2011; Liu et al., 2016); through mistreatment and discrimination (Wong and Waite, 2017; Das, 2013); and through gene expression (Cole et al., 2015).

FUTURE DIRECTIONS IN SOCIAL WELL-BEING AT OLDER AGES

The most exciting opportunities to understand social well-being over the next decade or so build on new sources of data, new research questions, new analytic techniques, and new theoretical and conceptual models. Here are some examples.

Genes and the Social

Recent research has shown the extraordinary complexity of links between the social world and our genes. One example comes from the body of work by Steven Cole, John Cacioppo, and their colleagues on the relationship between genes, gene expression, and loneliness (Cole et al., 2015). The mechanisms linking them are being unraveled with the help of

new technology; the availability to the research community of banks of genotyped data; genotyping of respondents in large, longitudinal surveys like the Health and Retirement Study; new theoretical perspectives (Cacioppo et al., 2014); and interdisciplinary research teams.

Environments and the Social

Theoretical perspectives on activity space (Browning et al., 2017), combined with GPS and other mapping and tracking technologies, provide opportunities to understand the environments in which people spend their time and their interactions with others in the various spaces in which they conduct their lives (Cagney and York Cornwell, 2010). Linking of data from environmental sensors, for example, allows researchers to characterize particulate matter in the local environment and its association with various dimensions of health (Adams et al., 2016).

Physiological variation both affects and responds to social factors. For example, Das (2017) used data on salivary testosterone obtained from respondents in NSHAP to test hypotheses about social modulation of hormones and hormonal regulation of women’s sociality and finds evidence for both. Social support and social strain predict inflammation later, with social support modestly protecting against inflammation and social strain substantially increasing the risks (Yang et al., 2014).

Direct observation gets personal. The popularity and ubiquity of fitness and health tracking devices has begun to change the way data on health and functioning are collected in survey research and will ultimately change clinical practice, too. These devices can now measure heart rate, blood pressure, sleep, exercise, and activity (now mostly in steps taken) over the day. They can identify location of the wearer. Nearness to other device wearers could track social contacts.

Creation of Global Measures of Social Well-being

Following on the example of measures of labor force participation, it should be possible to create measures of social well-being. These could be included, for example, in the Current Population Survey done by the U.S. Census Bureau or in the American Community Survey. Doing so would enable characterization of the social well-being of the population by subgroups and the use of these measures as social indicators. One approach is illustrated by an effort by the OECD, which has produced a conceptual framework for well-being indicators and is compiling these across countries (OECD, 2011). This global indicator of well-being includes “social contact with others” and “social network support” to compare measures of social connections across countries. Each indicator of well-being is char-

acterized for each country as falling either in the top two deciles of OECD countries, in the bottom two deciles, or in the six intermediate deciles. These two social measures are based on the Gallup World Survey, which asks respondents about their frequency of getting together with others and whether a respondent agrees that during times of need he or she can count on someone to help.

Various dimensions of social well-being have strong links, generally reciprocal, with physical, physiological, functional, psychological, and cognitive dimensions of health. Understanding these connections and how they operate constitutes future directions in the demography of aging.

REFERENCES

Adams, D., Ajmani, G.S., Pun, V.C., Wroblewski, K.E., Kern, D.W., Schumm, L.P., McClintock, M.K., Suh, H.H., and Pinto, J.M. (2016). Nitrogen dioxide pollution exposure is associated with olfactory dysfunction in older U.S. adults. International Forum of Allergy & Rhinology, 6(12), 1245–1252. doi: 10.1002/alr.21829.

Annandale, E. (2014). The Sociology of Health and Medicine: A Critical Introduction (2nd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Beck, A.H. (2004). The Flexner report and the standardization of American medical education. Journal of the American Medical Association, 291(17), 2139–2140.

Belsky, D.W., Caspi, A., Houts, R., Cohen, H.J., Corcoran, D.L., Danese, A., Harrington, H., Israel S., Levine, M.E., Schaefer, J.D., et al. (2015). Quantification of biological aging in young adults. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(30), E4104–E4110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1506264112.

Berkman, L.F., Glass, T., Brissette, I., and Seeman, T.E. (2000). From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Social Science & Medicine, 51, 843–857.

Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In: J. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education (pp. 241–258). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Bowling, A., Pikhartova, J., and Dodgeon, B. (2016). Is mid-life social participation associated with cognitive function at age 50? Results from the British National Child Development Study (NCDS). BMC Psychology, 4, 58. doi: 10.1186/s40359-016-0164-x.

Browning, C.R., Wallace, D., Feinberg, S.L., and Cagney, K.A. (2006). Neighborhood social processes, physical conditions, and disaster-related mortality: The case of the 1995 Chicago heat wave. American Sociological Review, 71(4), 661–678.

Browning, C.R., Calder, C.A., Krivo, L.J., Smith, A.L., and Boettner, B. (2017). Socioeconomic segregation of activity spaces in urban neighborhoods: Does shared residence mean shared routines? Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 3(2), 210–231. doi: 10.7758/RSF.2017.3.2.09.

Cacioppo, J.T., Cacioppo, S., and Boomsma, D.I. (2014). Evolutionary mechanisms for loneliness. Cognition & Emotion, 28(1), 3–21. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2013.837379.

Cagney, K.A., and Browning, C.R. (2004). Exploring neighborhood-level variation in asthma and other respiratory diseases: The contribution of neighborhood social context. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 19(3), 229–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30359.x.

Cagney, K.A., and York Cornwell, E. (2010). Neighborhoods and health in later life: The intersection of biology and community. Annual Review of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 30(1), 323–348. doi: 10.1891/0198-8794.30.323.

Cagney, K.A., and York Cornwell, E. (2017). Aging in activity space: Results of smart-phone based GPS tracking of urban seniors. Journal of Gerontology Series B: Psychological and Social Sciences, 72(5), 864–875.

Cagney, K.A., Browning, C.R., Iveniuk, J., and English, N. (2014). The onset of depression during the great recession: Foreclosure and older adult mental health. American Journal of Public Health, 104(3), 498–505. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301566.

Chen, J., Lauderdale, D.S., and Waite, L.J. (2016). Social participation and older adults’ sleep. Social Science & Medicine, 149, 164–173. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.045.

Chetty, R., Stepner, M., Abraham, S., Lin, S., Scuderi, B., Turner, N., Bergeron, A., and Cutler, D. (2016). The association between income and life expectancy in the United States, 2001–2014. Journal of the American Medical Association, 315(16), 1750–1766. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.4226.

Cole, S.W., Capitanio, J.P., Chun, K., Arevalo, J.M.G., Ma, J., and Cacioppo, J.T. (2015). Myeloid differentiation architecture of leukocyte transcriptome dynamics in perceived social isolation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(49), 15142–15147. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1514249112.

Coleman, J. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94, S95–S120.

Coontz, S. (2008). The Future of Marriage (Cato Unbound, January 14, 2008). Washington, DC: Cato Institute. Available: www.cato-unbound.org/2008/01/14/stephanie-coontz/future-marriage [March 2018].

Cornwell, B. (2012). Spousal network overlap as a basis for spousal support. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74(2), 229–238.

Cornwell, B., and Laumann, E.O. (2011). Network position and sexual dysfunction: Implications of partner betweenness for men. American Journal of Sociology, 117(1), 172–208.

Cornwell, B., Schumm, L.P., Laumann, E.O., and Graber, J. (2009). Social networks in the NSHAP Study: Rationale, measurement, and preliminary findings. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 64B(S1), i47–i55.

Cornwell, B., Schumm, L.P., Laumann, E.O., Kim, J., and Kim, Y. (2014). Assessment of social network change in a national longitudinal survey. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69(Suppl 2), S75–S82. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu037.

Croezen, S., Avendano, M., Burdorf, A., and van Lenthe, F.J. (2015). Social participation and depression in old age: A fixed-effects analysis in 10 European countries. American Journal of Epidemiology, 182(2), 168–176. doi:10.1093/aje/kwv015.

Das, A. (2013). How does race get “under the skin”?: Inflammation, weathering, and metabolic problems in late life. Social Science & Medicine, 77, 75–83.

Das, A. (2017). Network connections and salivary testosterone among older U.S. women: Social modulation or hormonal causation? Journals of Gerontology: Series B, gbx111. Epub prior to printing. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbx111.

Dong, X.Q., Simon, M.A., Rajan, K., and Evans, D.A. (2011a). Association of cognitive function and risk for elder abuse in a community-dwelling population. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 32(3), 209–215. doi: 10.1159/000334047.

Dong, X.Q., Simon, M.A., Beck, T.T., Farran, C., McCann, J.J., Mendes de Leon, C.F., Laumann, E.O., and Evans, D.A. (2011b). Elder abuse and mortality: The role of psychological and social wellbeing. Gerontology, 57(6), 549–558. doi: 10.1159/000321881.

Engel, G.L. (1977). The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science, 196(4286), 129–136.

Ertel, K.A., Glymour, M.M., and Berkman, L.F. (2008). Effects of social integration on preserving memory function in a nationally representative U.S. elderly population. American Journal of Public Health, 98(7), 1215–1220.

Flexner, A. (1910). Medical Education in the United States and Canada. Washington, DC: Science and Health Publications.

Fredman, L., Lyons, J.G., Cauley, J.A., Hochberg, M., and Applebaum, K.M. (2015). The relationship between caregiving and mortality after accounting for time-varying caregiver status and addressing the healthy caregiver hypothesis. Journals of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 70(9), 1163–1168. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glv009.

Galinksy, A, and Waite, L. (2014). Sexual activity and psychological health as mediators of the relationship between physical health and marital quality. Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69(3), 482–492. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbt165.

Galinsky, A., McClintock, M.K., and Waite, L.J.. (2014). Sexuality and physical contact in National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project Wave 2. Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 69(Suppl 2), S83–S98. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu072.

Glenn, N.D., and Weaver, C.N. (1979). A note on family situation and global happiness. Social Forces, 57, 960–967.

Goldman, A.W., and Cornwell, B. (2015). Social network bridging potential and the use of complementary and alternative medicine in later life. Social Science & Medicine, 140, 69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.07.003.

Hawkley, L.C., and Capitanio, J.P. (2015). Perceived social isolation, evolutionary fitness and health outcomes: A lifespan approach. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 370(1669). doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2014.0114.

House, J.S., Landis, K.R., and Umberson, D. (1988). Social relationships and health. Science, 241(4865), 540–545.

Hughes, M.E., Waite, L.J., Hawkley, L.C., and Cacioppo, J.T. (2004). A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: Results from two population-based studies. Research on Aging, 26(6), 655–672.

Huisingh-Scheetz, M., Kocherginsky, M., Schumm, L.P., Engelman, M., McClintock, M., Dale, W., Magett, E., Rush, P. and Waite, L. (2014). Measuring functional status in the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP): Rationale, measurement, and preliminary findings. Journals of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 69(Suppl 2), S177–S190. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu091.

Iveniuk, J., and Waite, L. (forthcoming). The psychosocial sources of sexual interest in older couples. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships.

Jessup, N.M., Bakas, T., McLennon, S.M., and Weaver, M.T. (2015). Are there gender, racial, or relationship differences in caregiver task difficulty, depressive symptoms, and life changes among stroke family caregivers? Brain Injury, 29(1), 17–24. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2014.947631.

Kalmijn, M., and Monden, C.W.S. (2006). Are the negative effects of divorce on psychological well-being dependent on marital quality? Journal of Marriage and Family, 68(6), 1197–1213.

Kaufman, M. (2018). Redefining Success in America: A New Theory of Happiness and Human Development. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kim, J., and Waite, L.J. (2014). Relationship quality and shared activity in marital and cohabiting dyads in the National Social Life, Health and Aging Project, Wave 2. Journals of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 69(Suppl 2), S64–S74. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu038.

Kotwal, A.A., Kim, J., Waite, L., and Dale, W. (2016). Social function and cognitive status: Results from a U.S. nationally representative survey of older adults. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 31(8), 854–862. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3696-0.

Lauderdale, D.S., Schumm, L.P., Kurina, L.M., McClintock, M.K., Thisted, R.A., Chen, J., and Waite, L. (2014). Assessment of sleep in the National Social Life, Health and Aging Project. Journals of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 69(Suppl 2), S125–S133. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu092.

Laumann, E.O., Waite, L.J., and Das, A. (2008). Sexual dysfunction among older adults: Prevalence and risk factors from a nationally representative U.S. probability sample of men and women 57 to 85 years of age. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 5(10), 2300–2312.

Lee, D.M., Vanhoutte, B., Nazroo, J., and Pendleton, N. (2016). Sexual health and positive subjective well-being in partnered older men and women. Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 71(4), 698–710. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbw018.

Lin, N. (2001). Social Capital: A Theory of Social Structure and Action. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lindau, S.T., Laumann, E.O., Levinson, W., and Waite, L.J. (2003). Synthesis of scientific disciplines in pursuit of health: The Interactive Biopyschosocial Model. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 46(3), S74–S86.

Lindau, S.T., Schumm, P., Laumann, E.O., Levinson, W., O’Muircheartaigh, C.A., and Waite, L.J. (2007). A national study of sexuality and health among older adults in the U.S. New England Journal of Medicine, 357(8), 762–774. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067423.

Lindström, M., Hanson, B.S., and Östergren, P.O. (2001). Socioeconomic differences in leisure-time physical activity: The role of social participation and social capital in shaping health related behaviour. Social Science & Medicine, 52(3), 441–451.

Litwin, H., and Shiovitz-Ezra, S. (2010). Social network type and subjective well-being in a national sample of older Americans. Gerontologist, 51(3), 379–388.

Liu, H., and Waite, L.J. (2014). Bad marriage, broken heart? Age and gender differences in the link between marital quality and cardiovascular risks among older adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 55(4), 403–423.

Liu, H., Waite, L.J., and Shen, S. (2016). Diabetes risk and disease management in later life: A national longitudinal study of the role of marital quality. Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Social Science, 71(6), 1070–1080. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbw061.

Lowsky, D.J., Olshansky, S.J., Bhattacharya, J., and Goldman, D.P. (2014). Heterogeneity in healthy aging. Journals of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 69(6), 640–649. doi: 10.1093/Gerona/glt162.

Luo, Y., and Waite, L.J. (2011). Mistreatment and psychological well-being among the elderly: Exploring the role of psychosocial resources and deficits. Journals of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 66B(2), 217–229.

Maccoby, E.E. (1980). Social Development: Psychological Growth and the Parent-Child Relationship. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Martin, P., Kelly, N., Kahana, B., Kahana, E., Willcox, B.J., Willcox, D.C., and Poon, L.W. (2015). Defining successful aging: A tangible or elusive concept? Gerontologist, 55(1), 14–25.

McPherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L., and Brashears, M.E. (2006). Social isolation in America: Changes in core discussion networks over two decades. American Sociological Review, 71(3), 353–375.

Mendes de Leon, C.F., Cagney, K.A., Bienias, J.L., Barnes, L.L., Skarupski, K.A., Scherr, P.A., and Evans, D.A. (2009). Neighborhood social cohesion and disorder in relation to walking in community-dwelling older adults: A multi-level analysis. Journal of Aging and Health, 21(1), 155–171. doi: 10.1177/0898264308328650.

OECD. (2011). Compendium of OECD Well-being Indicators. OECD Better Life Initiative. Available: http://www.oecd.org/std/47917288.pdf [April 2018].

Oldenkamp, M., Hagedoorn, M., Slaets, J., Stolk, R., Wittek, R., and Smidt, N. (2016). Subjective burden among spousal and adult-child informal caregivers of older adults: Results from a longitudinal cohort study. BMC Geriatrics, 16, 208. doi: 10.1186/s12877-016-0387-y.

Offer, S., and Fischer, C.S. (2017). Difficult people: Who is perceived to be demanding in personal networks and why are they there? American Sociological Review. doi: 10.1177/0003122317737951.

Office of the Surgeon General. (2001). The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Promote Sexual Health and Responsible Sexual Behavior. Rockville, MD: Office of the Surgeon General.

Payne, C., Hedberg, E.C., Kozloski, M., Dale, W., and McClintock, M.K. (2014). Using and interpreting mental health measures in the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project. Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 69(Suppl 2), 99–116. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu100.

Pearlin, L.I., Schieman, S., Fazio, E.M., and Meersman, S.C. (2005). Stress, health, and the life course: Some conceptual perspectives. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 46(2), 205–219.

Putnam, R. (2000). Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Raley, R.K., Sweeney, M.M., and Wondra, D. (2015). The growing racial and ethnic divide in U.S. marriage patterns. The Future of Children/Center for the Future of Children, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, 25(2), 89–109.