4

Why Health Literacy?

The third session of the workshop featured two presentations on why health literacy is important to the health care enterprise’s stakeholders. Cathryn Gunther, vice president for global population health at Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. (Merck), spoke about the importance of health literacy from the perspective of a pharmaceutical company, and Bernard Rosof, chief executive officer of the Quality HealthCare Advisory Group, discussed the role of health literacy in achieving the Quadruple Aim. An open discussion with the panelists followed the two presentations.

A PHARMACEUTICAL COMPANY PERSPECTIVE ON WHY HEALTH LITERACY MATTERS1

One piece of good news about health literacy, said Gunther, is it is getting increasing attention around the globe. Several European countries, for example, found they were not getting the degree of comprehension about health topics that they had anticipated and are now starting to address this problem. Asian countries are also starting to address health literacy for the first time. “There is enormous opportunity around the globe to improve comprehension, and I would suggest all of us as key stakeholders in the health industry have a responsibility to address it,” said Gunther.

___________________

1 This section is based on the presentation by Cathryn Gunther, vice president for global population health, Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

Why is health literacy so important to Merck? The reason, said Gunther, is that the number one goal of a pharmaceutical company is to get the right medication to the right individual in a way that is comprehensible, that fits into the total care plan, and that helps the patient feel empowered regarding his or her health care. Reflecting on the health literacy experiences she has had during her career, both within the pharmaceutical industry and outside of it as a consultant, she said they all come back to appreciating the context of a patient’s life—where they are, where they are coming from, and the environment in which they live—and meeting them where they are.

The late George Merck, son of the company founder and company president, embedded the patient experience into the center of the company’s philosophy when he said, “We try never to forget that medicine is for the people; it’s not for the profits. The profits follow, and if we’ve remembered that, they have never failed to appear,” explained Gunther before listing some of the ways in which the pharmaceutical industry has contributed to society—the development of medications that turned HIV/AIDS from a death sentence to a treatable chronic illness; vaccinations for measles, mumps, rubella, diphtheria, polio, and other childhood diseases; and more recently, immunotherapies that are changing the prognosis for many cancers. Gunther said it is important to appreciate that Merck is a research-intensive biopharmaceutical company, one that understands that a new drug has no real value unless the person taking that drug understands what that medication is going to do for them so they can take ownership of their own care and adhere to the appropriate medication schedule. Health literacy, she added, is a big part of realizing that value, and the current objective at Merck is to focus a collaborative effort across the organization—research, manufacturing, and sales and marketing—to ensure that health literacy is an embedded theme throughout the company.

From that perspective, patients must be treated as partners in efforts to help them gain the knowledge they need to take their medications properly. Better yet, everyone, not just those who have a health issue, need to be partners in the effort to expand health literacy to make it part of learning to live a healthy life. As a sponsor for global population health efforts, Gunther says she is interested in health creation, health promotion, and prevention; to achieve those, health literacy should start at home. Often, she said, health literacy starts with the women who are health providers for the family, and sometimes the community and schools as well.

She then asked the workshop participants to imagine a person who, along with 70 percent of the American population, is either overweight or obese, and who is among the close to 6 percent of the population that has diabetes and three or more other medical conditions, such as hypertension, high cholesterol, sleep apnea, joint issues, and depression. That person, she said, may be taking as many as 12 different medications, and it is nearly

impossible to achieve what used to be called “compliance” and has now been softened to “adherence.” “It is difficult for any individual to comprehend that and take all those medications as prescribed, assuming the prescription and diagnoses are accurate,” said Gunther.

Many opportunities exist for communicating with patients and maximizing their comprehension about a medication, Gunther said. These opportunities arise as early as the start of a clinical trial when patients are given consent to join the trial, as well as when the company creates materials about dosing that are provided to individuals enrolled in trials, conducts targeted messaging to underrepresented populations as a means of recruiting trial participants from those populations, and posts lay summaries of each trial on a public website.2 One emerging area of contact occurs when the company solicits patient input into trial design and outcomes.

Opportunities for engagement continue after a product is approved. For example, when the company drafts the product label—the information that accompanies every medication when a patient picks it up from the pharmacy—it works with focus groups comprising individuals from the lay community who help refine the label’s language. The company also tests comprehension with panels of lay individuals, at least 25 percent of whom are on the lower end of the health literacy scale. “We consistently achieve about 90 percent comprehension across all levels of health literacy,” said Gunther, who described this approach as a new paradigm for designing patient inserts. She noted, too, that Merck has engaged in its own internal health literacy activities to make sure its 65,000 employees can understand the health-related benefits the company provides.

Antibiotic resistance is an important public threat that results, in part, from patients failing to understand the importance of adhering to the prescribed medication regimen. Gunther said that some patients believe they become resistant to the antibiotics, not that the bacteria do, because of inappropriate use of the drug. Patient comprehension, she said, plays a critical role in managing antimicrobial resistance and improving stewardship. Zika is another area in which the company recently engaged in a health literacy effort. In this case, Gunther and her colleagues worked with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Foundation to ensure that women of childbearing age in Puerto Rico had the necessary information to make an educated decision about the types of birth control they would choose to delay having a child during the Zika outbreak there.

Lastly, Gunther said:

From a global policy perspective, working with countries and policy makers around the world, we have made significant contributions to the

___________________

2 The website is anticipated to be operational in Europe in early 2019.

research that’s being done in Europe as well as in the United States, because we feel that health literacy is an incredibly important issue and one worth investing in.

ACHIEVING THE QUADRUPLE AIM: HEALTH LITERACY INTERVENTIONS AS AN ESSENTIAL COMPONENT3

In delivering health care, communication is a key ingredient, said Rosof, and achieving the Quadruple Aim of better care, improving the health of the community and population, affordable care, and patient and health care team satisfaction is not possible without a health literate population. As the delivery of health care continues to evolve in the United States, he said, health literacy can serve as an innovative and disruptive force that creates a new value equation for health care that includes the Quadruple Aim. “Let us think about health literacy that way, as a really disruptive technology to achieve our goal,” said Rosof, “one supported by science and patient experience and one designed to disrupt the old habits and existing ways of thinking that get in the way of making progress.”

The current design of today’s health care system requires patients and families to possess and demonstrate multiple skills, including understanding and giving consent, interacting with health professionals, and applying health information to different situations in a variety of life events. In that context, health literacy is the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand the health information needed to make appropriate health decisions. Health literacy, said Rosof, can only occur when system demands and complexities align with individual skills and abilities.

Two Institute of Medicine reports—To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System (IOM, 2000) and Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century (IOM, 2001)—detailed why health literacy is important, said Rosof. He noted that the only population-level study of health literacy skills conducted to date, the U.S. Department of Education’s National Assessment of Adult Literacy,4 found that only 12 percent of U.S. adults are health literate enough to understand and use health information effectively. “They may fail to understand critically important warnings on the label of over-the-counter medications or find it difficult to define a medical term, let alone negotiate the payer system and try to understand insurance,” said Rosof. In addition, some 24 million Americans, or nearly 9 percent of the U.S. population, are not proficient in English.

___________________

3 This section is based on the presentation by Bernard Rosof, professor of medicine, Zucker School of Medicine, Hofstra/Northwell, and chief executive officer, Quality HealthCare Advisory Group, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

4 See https://nces.ed.gov/naal (accessed December 25, 2017).

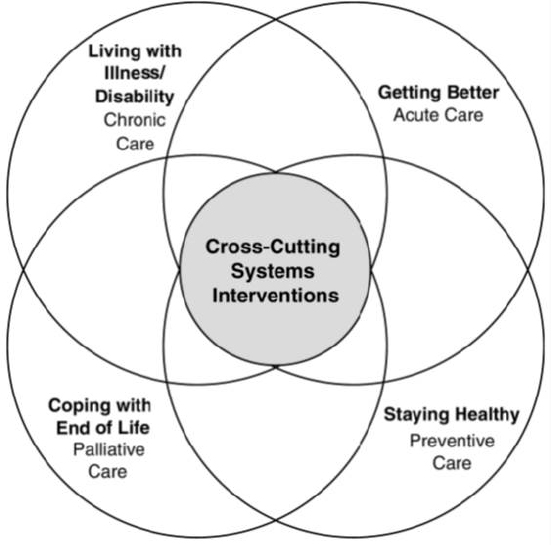

Regarding the priority areas for national action identified in Crossing the Quality Chasm to transform health care quality in the United States (see Figure 4-1), Rosof said quality is clearly a systems property. He noted that the priority areas did not focus on improving treatments through biomedical research or technological innovation, but instead focused on ways to improve the delivery of treatments and align system demands and priorities with individual skills and capabilities, the true definition of health literacy. He noted that the priority areas include acute care, preventive care, palliative care, and chronic care, all areas that should be familiar to the health literacy community, as well as cross-cutting systems interventions such as care coordination, self-management, and patient and family engagement that all require the presence of a health literate population.

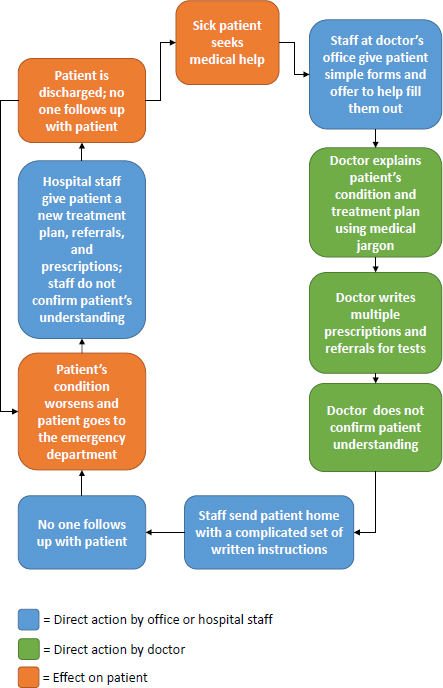

The cycle of crisis that characterizes health care delivery today (see Figure 4-2) is all too familiar, said Rosof. One of the drivers of this cycle is health illiteracy, which leads to patients taking their medications incorrectly or not understanding the importance of follow-up appointments. In a

SOURCE: As presented by Bernard Rosof at Building the Case for Health Literacy: A Workshop on November 15, 2017.

SOURCE: Adapted from a presentation by Bernard Rosof at Building the Case for Health Literacy: A Workshop on November 15, 2017.

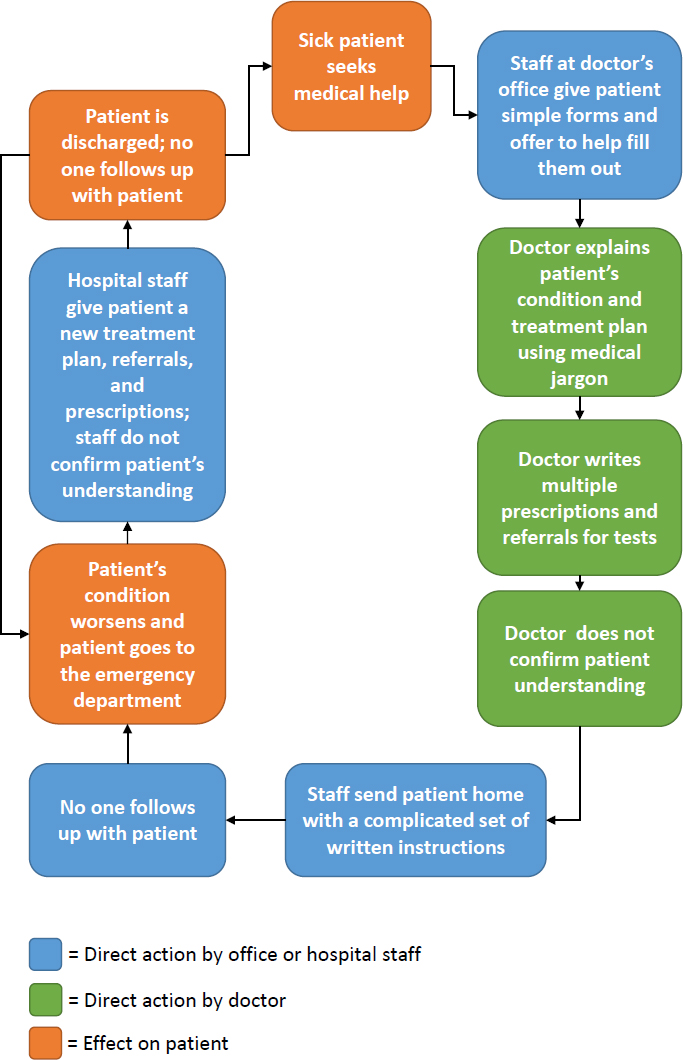

health literate patient experience (see Figure 4-3), the scheduler reminds the patient about coming back to the office, the physician and other members of the medical team explain things in a way that leads to comprehension, discharge information and medication instructions are easy to understand; and the result is a well-managed patient who does not need to return to the emergency department and is not readmitted to the hospital. Rosof noted that the way a team functions in the medical office is important in delivering health literate care.

Health literacy arrived at a tipping point, said Rosof, with the development of several new federal policies, including the ACA, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS’s) National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy, and the Plain Writing Act of 2010. It was then that health literacy was ready to move from the margins to the mainstream of health care, and become a national priority for the U.S. population to become health literate as a means of improving health care and health for all, Rosof said. The National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy (ODPHP, 2010) is based on two principles: that everyone has the right to health information that helps them make informed decisions, and that health services should be delivered in ways that are understandable and lead to health, longevity, and good quality of life. The Plain Writing Act of 2010 requires federal agencies to write documents clearly so the public can understand and use them. “I’ll leave that to your judgement as to whether that has actually occurred,” said Rosof.

One component of the ACA is that it required the Secretary of HHS to establish a national quality strategy that would achieve what was then called the Triple Aim, before the provision to improve patient and health care team satisfaction was added. The National Quality Strategy is an iterative, transparent, consultative, and consensus-building process that continues to be updated on a regular basis. The six priorities of the National Quality Strategy include health and well-being; prevention and treatment of the leading causes of mortality; providing person- and family-centered care; improving patient safety; engaging in effective communication and care coordination; and making care affordable. “If I had known enough about health literacy when we wrote the National Quality Strategy, I would have changed effective communication to health literacy,” said Rosof, who at the time chaired the committee that drafted the National Quality Strategy.

As far as who is at risk for low health literacy, Rosof said that men are at greater risk than women and that African Americans and Native Americans are at greater risk than whites and Asian Americans. Hispanics have the lowest skills among minority populations, and people 65 years and older have the lowest level of health literacy overall. As was discussed earlier in the workshop, patients with limited health literacy experience

SOURCE: As presented by Bernard Rosof at Building the Case for Health Literacy: A Workshop on November 15, 2017.

lower-quality communication, increased confusion regarding medical terminology, and insufficient time to express concerns. They fail to receive clear explanation and are less likely than others to use preventive services, all of which, Rosof explained, translates to poor outcomes. “When you begin to discuss social determinants of health associated with health literacy, you see that there are some areas of the United States where mortality and expectation for life may be 20 years less,” said Rosof.

A learning health system to better inform health literate practices and achieve the Quadruple Aim could improve this situation. A learning health system is one in which progress in science, informatics, and care culture align to generate new knowledge as an ongoing, natural byproduct of the care experience, and seamlessly refines and delivers best practices for continuous improvement in health and health care (IOM, 2007). “Building a learning health system around the concept of health literacy will enable an environment that has rapid-cycle learning and knowledge dissemination in which health literate research is continuously translated into practice and the care experience,” said Rosof. In simpler language, he explained, the health care system must take advantage of going digital and use the data available to compare outcomes, learn, and improve those outcomes. The key, he said, is to figure out how to do this routinely to create a learning health system. “Building a learning health system around the concept of health literacy will enable us to do this more efficiently,” he added.

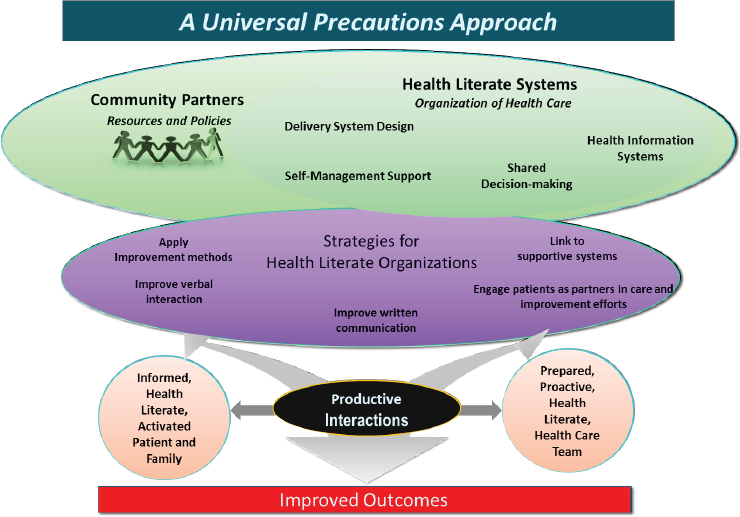

Among the principles of health literacy that need to be articulated and emphasized is that of universal precautions (see Figure 4-4). Just as hand-washing has become a universal precaution in infection control based on the assumption that every person in a health care setting is carrying a potentially dangerous microorganism with them, so too should it be assumed that every patient may have limited health literacy. “Health literacy is a state, not a trait, and everyone benefits from clear communication,” said Rosof. He explained that if there is a prepared, proactive, health literate health care team and an informed, health literate, activated patient and family, the result is a productive interaction and improved outcome.

AHRQ has developed a universal precautions toolkit.5 The 20-tool toolkit, said Rosof, includes a quick start guide, a path to improvement, sample forms, PowerPoint presentations, and worksheets. It also includes tips for communicating clearly, lessons on the teach-back method, and the brown bag medication review, which encourages patients to bring all of their medications, including over-the-counter medications, to the doctor’s office. None of this happens, however, in the absence of putting the patient

___________________

5 See https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/literacy-toolkit/index.html (accessed December 25, 2017).

SOURCE: As presented by Bernard Rosof at Building the Case for Health Literacy: A Workshop on November 15, 2017.

first and remembering that patient feedback is important to make the process work. The Joint Commission has weighed in, Rosof added, by stating the safety of patients cannot be assured without mitigating the negative effects of low health literacy and ineffective communication on patient care.

The 10 attributes of a health literate health care organization (Brach et al., 2012) are critical to creating a health literate health care organization, which makes it easier for people to navigate, understand, and use information to take care of their health, but it requires a charter for organizational professionalism (Egener et al., 2017) in order to develop, said Rosof. The charter for professional organizations includes four domains: patient partnership, organization of culture, community partnership, and operations and business practices. These domains, said Rosof, require communication in a health literate manner.

Rosof then noted 2 of the 10 attributes. Attribute 1 states that a health literate organization has leadership that makes health literacy integral to its mission, structure, and operations by not only making clear and effective communication a priority, but assigns responsibility for health literacy

oversight, sets goals for health literacy improvement, and allocates fiscal and human resources to that effort.

Attribute 2 characterizes a health literate organization as one that integrates health literacy into planning, evaluation measures, patient safety, and quality improvement. “Health literacy and communication have to be measured to be certain that it is happening in the organization,” said Rosof. “It has to be integral to your quality improvement program, to your performance improvement program, and to the efforts on patient safety.”

The commissioned paper presented at the workshop, said Rosof, included published outcomes, all of which demonstrate clear improvements in a health literate organization. These included

- A congestive heart failure self-management program, which reduced hospitalization rates and mortality by 35 percent (Berkman et al., 2011a);

- A diabetes self-management program using health literacy strategies in patients with limited literacy achieved success of 42 percent versus 15 percent without such strategies (Rothman et al., 2004);

- A randomized controlled trial of the “reengineered discharge” reduced rehospitalization by 30 percent (Jack et al., 2009);

- Plain language, pictogram-based medication counseling produced fewer medication errors (5.4 percent versus 47.8 percent) and greater adherence (38 percent versus 9.3 percent) (Yin et al., 2008); and

- Improving providers’ communication skills resulted in patients having higher colon cancer screening rates than a control group (55.7 percent versus 30 percent) (Ferreira et al., 2005).

Rosof noted that many members of the American Hospital Insurance Plan have undertaken explicit health literacy initiatives to improve patient outcomes. One such study, for example, estimated the effect of health literacy on selected health outcomes, controlling for education, income, race, and language, and found significant improvements in patient outcomes (see Table 4-1), all of which should translate into greater income for a health care institution. Rosof ended his presentation by drawing the following conclusions:

- Best care and improved population health requires adherence to health literate principles.

- Cross-cutting interventions to achieve the quality goals of the National Academy of Medicine and the National Quality Strategy require bilateral health literate communication and an alignment of system demands and complexities with individual skills and capabilities.

| Outcome | Population | Population Average (County Level) | Impact of Moving from Low-to High-Literacy Community |

|---|---|---|---|

| Avoidable ED visit rate | Commercial UHC | 44.1 per 1,000 | Reduction of 4.3 per 1,000 (−10.1%) |

| Avoidable hospitalization rate | Commercial UHC | 5.4 per 1,000 | Reduction of 1.0 per 1,000 (−18%) |

| Medication adherence rate | Commercial DM | 81.4% adherent* | Increase of 2.4 percentage points in adherence (+3.1%) |

| Readmission rate | FFS Medicare | 17.7% | Decrease of 1.2 percentage points (−7%) |

| ED visit rate | FFS Medicare | 645.8 per 1,000 | Reduction of 100.5 visits per 1,000 (−15%) |

NOTES: * = adherence rate is lower than 81.4 percent in a general population; DM = diabetes medication; ED = emergency department; FFS = fee-for-service; UHC = UnitedHealthcare.

SOURCE: Adapted from a presentation by Bernard Rosof at Building the Case for Health Literacy: A Workshop on November 15, 2017.

- Efficiency in the delivery of health care, particularly in the treatment of chronic disease, requires health literate skills.

- Enhancing patient and health care team satisfaction and mutual trust, improving adherence, and diminishing burnout requires optimum communication skills.

DISCUSSION

Jay Duhig from AbbVie Inc. began the discussion by asking if it is possible to make the process of creating health literate materials open source, that is, could the process of creating those materials be transparent and available for others to use to create their own materials? He noted that his efforts, for example, benefitted from Laurie Myers at Merck sharing best practices with him. In his mind, a mechanism like ClinicalTrials.gov, where organizations would publish their materials, the goals of and processes for developing those materials, and any outcomes data associated with the use of the materials, would accelerate progress and address systemwide needs.

Gunther replied that she and her colleagues are starting to publish some of their results. “My preference is always to elevate all the boats in the ocean and share those because this is not a problem that just resides with the one drug’s manufacturer, but it is a systemic opportunity,” she said. She noted that the Food and Drug Administration has expressed interest in

Merck’s work and believes it is a result of the agency recognizing the importance of health literate labeling. “Perhaps we can provide insights such that they will start to create some best practices that they would encourage all device manufacturers, as well as diagnostics and pharmaceutical companies, to abide by,” said Gunther. In her mind, that would be just one example of the opportunities all stakeholders have to create a learning health care system. Rosof agreed that total transparency would drive performance improvement because there would be more shared data and more metrics to demonstrate what improvement looks like.

Linda Harris from the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion at HHS noted that the commissioned paper and many of the comments at the workshop have assumed that health literacy will thrive in a value-based system of care, but given the current political climate, she wondered about the prospects of getting to such a system in the absence of federal leadership. Rosof said that he does not believe this transformation depends on a federal initiative, but rather on local initiatives. In his experience and from what he sees happening, he believes that most health systems are prepared to move from a fee-for-service environment to a value-based environment. He believes, in fact, that it is already embedded in daily activities and discussed at the level of health system boards, medical staff meetings, and even in medical schools.

Harris then asked if anyone has built a case for health literacy to be a driver of value-based organizations, rather than being dependent on the existence of a value-based care. Rosof replied that if the assumption is that consumer-based care needs to be health literate, then the evidence makes that argument clearly because health literate care produces better outcomes, reduces mortality, and saves money. “I do not see how we can ask for anything more,” said Rosof. Christopher Dezii from Bristol-Myers Squibb, commenting on Rosof’s remark that health literacy is essential for meeting the four aims, added that without health literacy, patient engagement will not happen, and neither will shared decision making or informed consent. After reading the commissioned paper and hearing the authors’ presentation at the workshop, Dezii said he is convinced the case for health literacy has been built. He suggested that the patient engagement literature would be another place to look for research on the effectiveness of health literacy interventions and future research should take the form of quality improvement work as a means of generating the measures that matter. Rosof noted that a newly published book on health literacy by Robert Logan (Logan and Siegel, 2017) will help spread the word.

Katherine Atchison from the University of California, Los Angeles, remarked that effective communication among the entire health care team, not just the physicians and nurses, is imperative for achieving a health literate health care organization. Rosof agreed completely, noting that the

health care team is not restricted to the team that sits within the hospital or within the ambulatory care setting; it can also include community resources and social services. Wilma Alvarado-Little from the New York State Department of Health said she would include someone from the spiritual community and mental health community as part of the health care team when appropriate, as well as interpreters for those who are visually or physically challenged. Gunther added that there are other individuals on the payer side who are also part of the care team, including case navigators and case managers who work with insurance companies to help patients navigate their care. In her opinion, there are opportunities for working with employers to enhance wellness and health literacy. “I think there are many strange bedfellows we could tap to increase communication and education needed to improve health literacy,” she said.

Sochan Laltoo, a public health instructor from Trinidad and Tobago, asked Gunther to comment on how health literacy plays into the growing acceptance of so-called natural remedies as replacements for pharmaceuticals when there is little or no evidence for the efficacy of those natural remedies. He also asked how increasing health literacy might reduce the inappropriate use of antibiotics. On the antibiotic issue, Gunther said the pharmaceutical industry is doing a great deal of work to (1) educate both the public and the medical profession, including dentists, veterinarians, and others, and (2) establish better guidelines on antimicrobial stewardship. Regarding natural remedies, Gunther said her company’s responsibility is to invent medications that prove effective in the clinic and provide as much information as possible to regulators, so they can decide whether those medications are safe and effective. It then becomes her company’s responsibility to provide balanced marketing information about that new drug. In her opinion, it is important for patients to take responsibility when they are given a prescription to ask what the medication is, why they are taking it, and if there are alternatives. “We have to appreciate, though, that not every human being is equipped to ask those questions in that moment, and that is where health literacy and improved communication skills from physicians comes in,” said Gunther. “I think there are benefits to both of those types of holistic, herbal, and medicinal drugs, but the risks and benefits should be carefully weighed for each individual and it needs to fit their cultural predisposition as well.”