3

Improving Health and the Bottom Line: The Case for Health Literacy

The workshop’s second session featured presentations by two of the four authors of the paper commissioned for the workshop: Stanton Hudson, associate director of the Center for Health Policy at the University of Missouri, and R. V. Rikard, senior research associate in the Department of Media and Information at Michigan State University. An open discussion followed their presentation.

PRESENTATION OF THE COMMISSIONED PAPER1

Before discussing the commissioned paper, Hudson told the workshop attendees that he and his colleagues also created a series of fact sheets that can be used to present information on the impact of health literacy. He also noted that his team’s plain language specialist revised the paper’s executive summary so it could be understood by people outside of the field, and he thanked the more than 50 people he and his colleagues spoke with to find out what new evidence was available and identify best and promising practices that have not been published in the peer-reviewed literature. He

___________________

1 This section draws on a paper commissioned by the Roundtable on Health Literacy, Improving Health and the Bottom Line: The Case for Health Literacy, by Stanton Hudson, R. V. Rikard, Ioana Staiculescu, and Karen Edison (see Appendix C) and is based on the presentation by Stanton Hudson, associate director of the Center for Health Policy at the University of Missouri, and R. V. Rikard, senior research associate in the Department of Media and Information at Michigan State University, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

explained that there is a great deal of quality improvement work underway in hospitals that has not yet appeared in the peer-reviewed literature.

At the start of their work on the commissioned paper, Hudson and his colleagues realized that there are several challenges to making the case for health literacy, and even with a compelling case, there are aspects of the U.S. health care system that hinder the argument. Volume-based reimbursement incentives, for example, are an impediment, although the ongoing transition to value-based reimbursement should ease that barrier.

A second challenge is the overall lack of transparency in the U.S. health care system. “We want people to be active, engaged health consumers, health customers, but if you cannot shop around for price, or you cannot tell the quality of the products you are buying, then it makes it virtually impossible,” said Hudson. Quoting James Duesenberry, Hudson said, “Economics is all about how people make choices. Sociology is all about why they don’t have any choices to make.” The goal may be to empower patients to make choices, he said, but they are trying to work within systems and against policies and structures that limit patient choice at almost every level. He stated that until the health care system and policies that govern it change, it will be challenging for well-intentioned patients to make well-informed choices even when presented with health literate information.

A third challenge to making the case for health literacy is that the legal profession has not yet embraced the literacy movement and can function as a barrier. As an example, Hudson recounted how frequently he and his colleagues have reworked documents, often with the help of patients, for Missouri’s Medicaid program only to have lawyers reject the changes. He did note that some of the younger lawyers are starting to get that plain language can reduce, not increase, liability, but until the legal profession is convinced about the importance of plain language, the legal profession will continue to be a challenge.

Rikard then discussed the fourth challenge, which is the need for research to support the efficacy of health literacy interventions. Most of the research that has been done, he said, has looked at short-term outcomes. There have been no longitudinal studies involving health literacy that examine long-term outcomes related to cost, quality, satisfaction, and effects of broad-based health literacy initiatives and interventions, which makes it difficult to identify causal relationships between health literacy and improved outcomes. Rikard conceded that there could be useful evidence in the literature that does not turn up in a search using the term “health literacy.” He also noted that Hudson heard in informal conversations with researchers that when an intervention does not work, it is difficult to get funding to try a different approach.

To prepare the case for health literacy, Hudson and his colleagues first looked at what they called the business case, which he explained speaks

SOURCE: As presented by Stanton Hudson and R. V. Rikard at Building the Case for Health Literacy: A Workshop on November 15, 2017.

to the factors that go into the Quadruple Aim and is aimed primarily at hospitals. They then looked at the ethical case. There are areas of overlap between the two, he said, given that health literacy can affect behavior change and patient experience as well as cost, quality, and access.

When the authors of the commissioned paper looked at the business case (see Figure 3-1) they started by looking for recent studies on cost that had not been included in a systematic review published in 2011 (Berkman et al., 2011a,b) and identified quite a few ways in which health literacy can improve the bottom line. For example, one health literacy intervention found that some 18 percent of individuals who received an automated phone call to remind them to have a cancer screening did, in fact, get screened, generating nearly $700,000 in additional income for the health system in 2 months. When Massachusetts General Hospital hired a community resource specialist, emergency department visits fell by 13 percent and realized a net annual savings of 7 percent, generating a return on investment of $2.65 for each $1.00 spent on the community resource specialist.2 Even something simple, such as giving parents the book What to Do When Your Child Gets Sick, produced savings of $1.50 for every $1.00 spent by giving parents easy-to-understand information on how to deal with their child’s

___________________

2 Information available at http://www.partners.org/Innovation-And-Leadership/Population-Health-Management/Current-Activities/Integrated-Care-Management-Program.aspx (accessed December 24, 2017) and https://www.advisory.com/research/market-innovation-center/the-growth-channel/2017/04/health-disparities (accessed December 24, 2017).

health care at home. Another study found that using the teach-back method at the appointment desk reduced no-shows by 15 percent. In short, said Hudson, while health literacy is not a magic bullet for controlling health care costs in the United States, there are many health literacy interventions that can produce significant cost savings.

Behavior change is also part of the business case, and Rikard discussed several examples that were not in the peer-reviewed literature. One study found that when new mothers-to-be received What to Do When Your Child Gets Sick, they used the emergency department less frequently because they had an understandable resource at hand that they could use when their children were sick. In another study, heart failure patients received phone calls asking patients to call in and report their weight. Over the first 2 weeks, the percentage of patients who reported their weight daily increased from 28 percent to 36 percent, and more importantly, these patients who called in lost weight. A third study found that when an adult education class added health literacy into the curriculum, the adult learners increased their knowledge about health and what they needed to do regarding prevention. “These are one-off studies, but we see that there are these behavioral changes that happen as a result of maintaining a health literacy practice,” said Rikard.

When Hudson and his colleagues looked at health outcomes, one of the promising new developments they found was the increased use of multimedia programs and associated YouTube videos as mechanisms to provide information to people in forms they can understand. One study, for example, found that individuals who used a video education program were more likely to have controlled blood pressure, regardless of their blood pressure control status, than were those who relied on written information. Similarly, video education programs benefitted individuals with other chronic conditions, such as producing improvements in glycemic control in patients with diabetes. Combining online interactive media with automated phone calls produced a 15-day delay in readmission for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and a 69 percent reduction in length of stay when patients did have to be readmitted to the hospital. Another study found that a patient navigator program for individuals with heart failure produced a 15.8 percent decrease in unplanned readmissions. Hudson noted that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is now penalizing health systems for readmissions and that private insurers are likely to follow suit, so hospitals are desperate for approaches to reduce readmissions, such as Project RED (Re-Engineered Discharge), which increases support for people upon discharge from the hospital.

In some cases, said Hudson, realizing improvement can require some unexpected interventions. His hospital, for example, has been struggling with getting its congestive heart failure patients to report their daily weights.

The first issue, it turns out, was that many of these patients did not have a scale at home or know how to use it. Even after providing a scale and testing their knowledge about how to use it, the hospital staff was still having trouble getting them to report their daily weight, which turned out to be because they were being asked to report daily weight change, which required them to do math. When the patients were asked to report daily weight instead, compliance improved by 18 percent. Understanding these little challenges and being able to put supports in place, said Hudson, can help patients overcome these challenges.

Hudson said he was surprised how little literature there was that tries to understand the causal relationship between health literacy and medical errors. Perhaps the one exception is there have been quite a few studies showing that health literacy improves medication adherence and reduces medication errors (NASEM, 2017). There are clear guidelines, for example, to use milliliters instead of teaspoons and tablespoons to stop people from using kitchen cutlery to measure liquid medication, and these guidelines have made a difference as far as reducing dosing errors. Hudson noted that the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) developed and adopted a patient-centered medication label format to improve the quality of care for veterans.

One of the statistics that Hudson quotes whenever talking about health literacy is that patients forget between 40 and 80 percent of what the doctor tells them as soon as they leave the doctor’s office. More worrisome, though, is the fact that half of what patients do remember, they remember incorrectly (Kessels, 2003). “That is where those mistakes are going to be made that are really going to impact not only the health system and cost, but the lives and quality of life of those patients,” said Hudson. He also commented that the United States has a mixture of health care systems. “We have socialized medicine in the VA and the Indian Health Service. We have employer-sponsored health plans. We have a national health insurance, Medicare, like they have in Canada, and trying to make these all work can be very challenging,” he said.

In his opinion, the VA is leading the way when it comes to improving the quality of care, and while the VA has its own challenges and issues, one big advantage is that its EHR can communicate across the entire VA system. As an aside, Hudson noted his hospital uses one vendor’s system and the other hospital in town uses a second system, and the result is that the two hospitals must fax patient information between them. Referring to the VA’s patient-centered medication label, he said the label is currently being tested and he is curious about whether it will make a difference in reducing medication errors. He also noted that the one study he found that looked at the relationship between health literacy and costs was conducted at the VA (Haun et al., 2015). That study found that in a population of

more than 93,000 veterans, the ones with marginal to low health literacy spent $143 million more over a 3-year period compared to those who had adequate health literacy.

For the care experience, the authors of the commissioned paper found an unpublished study showing that 100 percent of the hospitals employing commercially developed and implemented video programs scored higher on the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS), the patient experience survey CMS requires from all U.S. hospitals. This survey may serve as a proxy for patient satisfaction. That satisfaction is enhanced, said Rikard, by coupling video programming with telephone-based education and support services. He also explained that health literacy solutions do not have to be extensive or expensive. As examples, he cited rewording imaging and other diagnostic test reports, standardizing emergency department instructions, employing audio-recorded messages, and encouraging patients to bring a family member or friend to an appointment, all of which have been found to improve the patient’s experience and satisfaction. The crucial step, said Rikard, is to meet people where they are in terms of their health literacy.

Turning to the ethical case for health literacy (see Figure 3-2), Hudson said that health literacy is the right thing to do. He referred to Martin Ratermann’s challenge in the workshop’s first session to not be an industry that does not take care of its customers and does not communicate well with its consumers. “We need to get past that and become more customer-oriented and customer-focused,” said Hudson.

SOURCE: As presented by Stanton Hudson and R. V. Rikard at Building the Case for Health Literacy: A Workshop on November 15, 2017.

Regulations play a significant role in making the ethical case, as well as the business case, Hudson explained. CMS regulations for home health agencies and long-term care facilities, for example, require that information be provided in ways the patient can understand and in culturally appropriate forms. A bigger factor, however, will be the requirement in the Medicare Access and CHIP (Children’s Health Insurance Program) Reauthorization Act that states that half of all reimbursement for those two programs will be through value-based payment arrangements, either through the merit-based incentive payment system or one of several alternative payment models. One aspect of these new reimbursement models is that they will pay for health literacy activities, which Hudson called a promising development. For Hudson, one of more interesting demonstration projects enabled by the ACA bases physician bonuses on HCAHPS scores, which means the consumer has a voice in how much the doctor and the health system get paid. Another promising development is that most state Medicaid programs—42 by his count—are using an alternative payment model, such as medical homes, to reimburse physicians and incentivize effective quality care. One effect of these policy changes, said Hudson, is that they will force hospitals to switch from a model that tries to keep beds filled to one that has to keep people out of the hospital, which helps create a true health care system rather than the current sick care system.

Health equity is another aspect of the ethical case, explained Rikard, and from a health literacy perspective, health equity means that everyone has equal access to health information on which they can act. In many cases, he said, people who do not have health information also lack access to health care services, and even if they have access, the information might be understandable by some, but not all. In addition, he added, the 2016 CMS Quality Strategy includes two goals related to health literacy and health equity.3 Goal 1 calls for improving safety and reducing unnecessary and inappropriate care by teaching health care professionals how to better communicate with people who have low health literacy and by more effectively linking health care decisions to person-centered goals. Goal 3 calls for enabling effective health care system navigation by empowering individuals and families through educational and outreach strategies that are culturally, linguistically, and health literacy appropriate

In Hudson’s opinion, the implications of health literacy for health policy and practice are best laid out in the 2012 Institute of Medicine discussion paper Ten Attributes of Health Literate Health Care Organizations (Brach et al., 2012). Once the case for health literacy is made, he said, this

___________________

3 See https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/QualityInitiativesGenInfo/Downloads/CMS-Quality-Strategy.pdf (accessed December 24, 2017).

paper, “lays out the road map for what facilities can do to really address that case and make a difference.” It is his hope, he said, that someday everything measured in health care around health literacy will be based on these 10 attributes, and that the health care enterprise will come to realize that these 10 attributes speak to the provider experience as much as the patient experience. As an example, he recalled hearing a presentation several years ago by Laura Noonan from the Carolinas HealthCare System showing that physicians who integrate the teach-back method into their practice had to spend less time with patients because they were using less jargon that needed to be reexplained.

Rikard and Hudson concluded their summary of the commissioned paper by listing recommended areas for future research. These included

- Assess the savings from long-term outcomes and behavior change, conduct longitudinal studies of broad-based health literacy activities.

- Change health behaviors and health outcomes, study whether public health literacy provides an upstream payoff.

- Ensure that information and communication technologies translate into better health outcomes, examine the effect of eHealth literacy interventions on health outcomes.

- Understand the direct relationship between health literacy and medical errors, examine the causal link between health literacy and adverse events.

- Examine the link between health literate organizations and provider–patient communication, develop evidence on the direct relationship between health literacy and provider satisfaction.

- Achieve health equity, focus on the effect of the health care power dynamic on health equity and opportunities for people to achieve a healthy life.

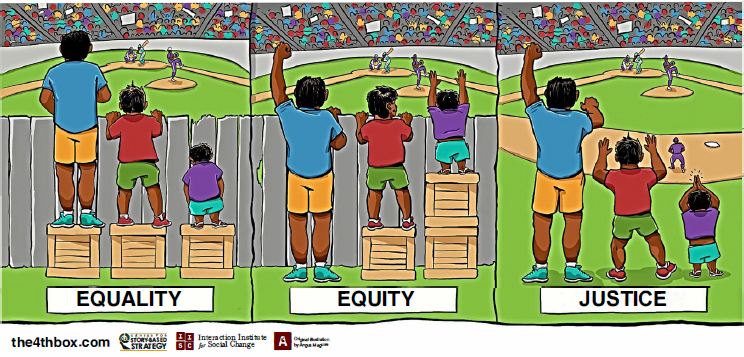

In thinking about health equity, which is where Hudson said his interests lie, he referred to the illustration showing the difference between equality and equity (see Figure 3-3). “Equality is where we give everyone the same box to see over the fence, and equity is where we provide different supports to patients,” he explained. “That is where we are now, identifying our patients that struggle and trying to give them a little extra support.” Where he would like to see the health care system move to is a place that recognizes the structures and policies that create inequity, Hudson said:

It is the fact that we do not have EHR interoperability, so we have to rely on patients for their information. It is the fact that we have siloed and disjointed health care, which is something that stares patients in the face. It is the fact that we do not have transparency of information. We need to

SOURCES: Image presented by Stan Hudson and R. V. Rikard at the Building the Case for Health Literacy workshop, adapted from Angus Maguire, Interaction Institute for Social Change, and from Craig Froehle.

tear down those systems and recreate them so that people can see through that fence. Then we do not have to worry about providing special support, and we create an equitable system for everybody to be able to navigate and get in the game, so to speak.

DISCUSSION

Terry Davis from the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center in Shreveport opened the discussion by commenting on the use of automated call prompting. In her recent experience, automated text messages are producing better responses from patients because so many people have stopped answering their phones when they do not recognize the phone number that is calling them. She also remarked that while research has largely focused on what the system must do and some on what the patient must do, there is little in the literature about family caregivers; but as society ages, family caregivers are going to play an increasingly vital role in health literacy.

Lawrence Smith from Northwell Health stated that the health care system needs to teach patients two things: enough information about their illnesses so they can be legitimate partners with the health care system in the appropriate management of their illness, and equally important, how the health care system works. “In fact, if the patients don’t under-

stand how the health system works,” said Smith, they will be “endlessly surprised” by the “traps” they will encounter. He expressed concern about the suggestion that the language of imaging reports and the like should be changed so patients can understand them, when in fact, the precision of medical terminology in a report intended to go from one expert to another should not be diluted to the level of a lay person. “I would strongly object to someone changing the way a neuroradiologist reports findings on an MRI [magnetic resonance imaging] scan to a physician who ordered it looking for specific things,” said Smith. Perhaps what is needed, he suggested, is a summary that provides the take-home message for the patient who is going to look at the medical record. He noted that this would require “a tremendous culture change, and I do not know whether medicine is ready or not.”

Smith then commented that patients who are mad at the health care system need to realize that the physicians working in that system are also unhappy. Each year, he said, Northwell Health surveys its 18,000 physicians and asks if they think about leaving the practice of medicine, and if so, why. Every year, the top reason why physicians think about giving up their practices is frustration with the EHR. In fact, said Smith, the level of patient dissatisfaction with the health care system pales in comparison to the dissatisfaction physicians express about the EHR. He reminded the audience that the EHR was designed for chief financial officers, not physicians, and relayed the cynical message he got from the vice president of one of the major EHR vendors, which was his company did not care about doctors or patients, because if the finance department was happy, they would keep buying this vendor’s products for their hospitals. “We are talking about an entire system that was designed to make everyone miserable except a very select few people,” said Smith.

As a final comment, Smith said that in his opinion, efforts to conduct randomized trials on interventions that involve partnering with patients and caregivers to reconstruct the health care system are perhaps misplaced. His suggestion was to find the natural experiments that have already take place and to identify the physicians who are already great communicators and health literacy teachers and find out how their patients have done.

Hudson responded to those observations with one of his own, which is that the system largely blames the patient for being health illiterate. “We expect individuals to have these skills, but we do not teach them,” he said. “If we truly wanted to teach health literacy, we would teach it in elementary and secondary school along with reading, writing, and math as a life skill everyone needs.” In fact, when someone asked him the night before the workshop for the most innovative study he found, he singled out a study in which the researchers were “democratizing medical education” by taking what medical students would learn and including it in elementary and sec-

ondary education. Until that happens on a large scale, however, patients are not going to have the necessary health literacy skills. “When you are learning on the fly, when you are sick, in pain, or worried about a family member, that is not the most conducive learning environment,” said Hudson.

Regarding Smith’s concern about rewording imaging reports, Hudson clarified that the idea is not to reword those reports but to provide a translation into a more understandable form for patients. The challenge will be to develop the necessary translation tools that will take the report designed to convey information from one expert to another into language suitable for the patient who is going to look at their medical record or use OpenNotes. The crucial step in developing such tools will be to involve patients in end-user testing. “The golden rule of health literacy is to know your audience and to test and develop with your audience,” said Hudson. “That is something the health system does not do like other industries.”

Kim Parson from Humana reiterated Hudson’s message that the health care system must stop blaming patients for what they do not know and take responsibility for conveying information in a way that is suitable for patients. “In my organization, we like to say, ‘It is not my fault, but it is my problem,’ and I think that is how we have to approach things.” She also agreed with Smith that it is right for two experts to use language that conveys information precisely when communicating between themselves and that it is just as right to recognize that not everyone is going to understand that language. “Therefore, it is incumbent upon the system to design and co-create with the people who are going to be the receivers of this information, and for those that are going to be navigating the system,” said Parson. “End-user testing is great, but I think we should start with the user at the beginning.”

Terri Ann Parnell from Health Literacy Partners asked Hudson if the videos used in the video-based interventions all came from the same company, which they did. Hudson noted that one thing this company does better than others is that they partner with researchers to make sure they get good evaluation data. This company also provides fact sheets and reports that document the effectiveness of its products, and it also reports when the videos have no effect and need further work. Parnell added that the videos that she has used from this company are also noteworthy in that they use language that is culturally appropriate.

In response to Parnell’s subsequent comment that medical schools are now doing better at teaching health literacy skills to medical students, Hudson said the problem is that similar efforts are not being made with attending staff and preceptors. “Students come out all gung-ho to use the teach-back method and they immediately get shut down by a doctor not understanding what they are doing, saying they do not have time for it,” said Hudson.

Laurie Francis from the Partnership Health Center remarked that the United States does not have a true health system because every organization and every state is different, which creates challenges. She also noted that the discussion about health literacy does not include team-based care as often as it should. Today, with patient-driven, patient-centered, team-based care, the doctor does not have to do everything, and since most doctors are not great communicators, perhaps more effort should be spent identifying those team members who are good communicators and training them in health literacy techniques. She then noted that teaching physicians motivational interviewing, health literacy, and power-sharing skills is an effective way of retaining physicians. “Physicians really enjoy it once they learn how to ask questions,” said Francis. She then asked if the VA studies that Hudson and Rikard found look at whether the cost savings were associated with health literacy alone or if the culture of the VA had an effect as well. Hudson replied that the VA study he cited was a 3-year retrospective study in which patients took a test to quantify their health literacy level and then the patients’ records were examined retrospectively to look at direct medical costs. “They did not extrapolate as much on other factors that could be playing out, and they were just trying to tie it to health literacy,” said Hudson.

Commenting on the idea of bringing a family member to medical appointments, Wilma Alvarado-Little from the New York State Department of Health pointed out that family members should not serve as interpreters because that robs the family member of their primary purpose, which is to provide support. She also reminded the workshop that doctors and nurses are not the only providers who see patients. Physical therapists, speech therapists, and other health care professionals who enter a patient’s room can be a provider who can be tapped to provide health literate information. She then asked the two speakers if any of the studies looking at performance measures did so through the lens of community-based organizations that do not provide specific direct services but do affect patients and the partners of those organizations. Hudson replied that the commissioned paper does include studies that looked at public health literacy interventions. He also noted that the Canyon Ranch Institute is using quality-adjusted life-years and similar measures to measure the effectiveness of interventions on cost and can identify extensive cost savings in that manner. One challenge, said Hudson, is that most of the research is focused on direct costs. “What we need is a longitudinal study that not only looks at multiple interventions at once, because we usually do not do health literacy one thing at a time, but also looks at indirect cost savings,” he said. “We do not talk about the lost years of productivity that result from medical errors and the people who die from them, and that is a huge cost to society.”

Stacey Rosen from Northwell Health asked the speakers if they found any pilot studies or reports on bringing health literacy education to elemen-

tary, middle, and high schools. Hudson replied that he and his colleagues only found one study, but they were not looking for them either since their focus was on the business case. Rikard mentioned there are studies of that type underway in Europe. Health Literacy Europe, he said, is implementing health literacy curricula in Europe’s primary and secondary schools and studying what happens to those children over time.4

Audrey Riffenburgh from Health Literacy Connections noted that she recently met a professor at the Colorado State University College of Veterinary Medicine and Biological Sciences who told her that the veterinary students all receive 50 hours of health communication skills as part of the standard curriculum. This faculty member told Riffenburgh that she and her colleagues have made two observations regarding this training. The first was that the clients of the veterinarians who had received this training were more likely to be repeat clients because they felt good about the communications they had with the veterinarian (Shaw et al., 2012). The second observation was that the clients were more likely to be compliant with treatment recommendations for their animals (Kanji et al., 2012).

Jay Duhig from AbbVie Inc. asked the speakers to discuss the barriers to conducting the future research they suggested. Rikard replied that the main barrier is there are no incentives for people, particularly from different fields, to work together on long-term projects. The National Institutes of Health, for example, does not have grant mechanisms to fund cross-discipline, long-term projects. Pleasant then asked what funders could do to address this barrier. Hudson replied that one challenge specific to health literacy studies is that many are funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), and the legislation authorizing PCORI does not allow it to fund cost-effectiveness research. While that may be a special case because that funder was created by Congress, Hudson said that giving more latitude to researchers to explore the breadth of the issue would be a key first step. Rikard added that he would start approaching large nonprofit institutions and foundations to interest them in the importance of health literacy in improving the health of the nation.

Casey Quinlan from ThinkProgress asked how much of a barrier is created by the status quo in a $3.5 trillion industry with little incentive to change and if it would be possible to make faster progress by involving patient communities in reform efforts. Hudson replied that he would like to see more funding for projects that bring in community investigators as equal members of the team and that involve the community in the planning process for these projects. In his opinion, doing so would save time and money by skipping the need for a redesign phase when a poststudy end-user group finds a problem with an intervention. He noted that the field is

___________________

4 See https://www.healthliteracyeurope.net/hl-and-eu-policy (accessed February 15, 2018).

getting better at engaging with the community and valuing the knowledge that community members bring to studies when they are involved at the beginning rather than the end of a project. Rikard added that a study he is working on regarding the water crisis in Flint, Michigan, is using paid community investigators who have made important contributions to the study design.

With the last comment of the discussion period, Cindy Brach from AHRQ commended the speakers for including the ethical case for health literacy in their paper because even if an intervention does not save money, patients have a right to communicate with and understand their health care providers. One part of the business case that was not mentioned, she said, concerns market share and patient loyalty. She suggested that these should be included in the business case because patients are more likely to return to a health care organization that communicates clearly. She also noted that changes in payment policies are providing new incentives that reward outcomes and positive patient experiences; these changes should become important pieces of the business case.