5

Adopting Health Literacy in an Organization

The workshop’s fourth panel featured three speakers and focused on how different organizations can adopt health literacy effectively. Audrey Riffenburgh, president of Health Literacy Connections, continued the discussion on the research base regarding adoption of health literacy. Chris Carlson, senior vice president for consumer and customer experience at UnitedHealthcare Shared Service Operations, then spoke about his organization’s experience with developing and adopting a health literacy plan. Jennifer Dillaha, medical director for immunizations and medical advisor for health literacy and communication at the Arkansas Department of Health, described how her organization adopted health literacy as part of the department’s strategic plan. An open discussion followed the three presentations.

WHAT RESEARCH SHOWS ABOUT ADOPTING AND IMPLEMENTING HEALTH LITERACY IN A HEALTH ORGANIZATION1

To start her presentation, Riffenburgh noted that she would be sharing the findings of her dissertation research, which she completed in 2017. Her research focused on the early phases of adoption and implementation of health literacy initiatives. In particular, she looked for factors

___________________

1 This section is based on the presentation by Audrey Riffenburgh, president, Health Literacy Connections, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

that advance or impede implementation of health literacy initiatives. Her research involved in-depth qualitative interviews with individuals in charge of advancing health literacy in health care organizations around the country. In some cases, these individuals were employed as full-time health literacy change leaders, while others spent half or less of their time on health literacy after somewhat grudgingly being given permission to do so. The organizations varied in size, how long they had been working on and had a person in charge of health literacy, and the populations they served. She cautioned that while her research identified some important themes, the findings are not generalizable to the entire U.S. health care system.

As with any study, Riffenburgh’s first step was to review the literature. She reviewed three different areas of research: organizational theory, organizational change theory, and what she characterized as an interesting and rich field called dissemination and implementation. (This last field is the source of the often-repeated finding that it takes 17 years for 14 percent of medical research to lead to care that benefits patients.) Riffenburgh’s study found many of the facilitators and barriers to implementation of new initiatives previously identified in the literature, such as the importance of leadership support; making the initiative a strategic priority; having executive sponsors, champions, and a task force; dedicating full-time employees, a budget, and an office; and having policies that support or mandate the initiative. “When these were present, they were facilitative, and when they were not present, it created all kinds of barriers,” said Riffenburgh. “It all centered on leadership support. If the leadership support was not there, then the things that flowed out from the leadership support were not there, and progress was going to be tough.”

In addition to the findings related to factors previously identified in the literature, there were findings and themes specifically related to health literacy initiatives. First, two distinct types of organizations emerged in the findings. In one type, advancing health literacy was so slow and difficult that one of the interviewees described it as “digging a tunnel with a tablespoon.” In the other type of organization, advancing health literacy was much faster and easier. In contrast to “digging with a tablespoon,” the second type of organization could be described as “creating a path with a backhoe.” In a “tablespoon” organization, people lack tools and resources, and they labor away largely hidden from the view of the rest of the organization. In a “backhoe” organization, people have enough resources to metaphorically “buy a backhoe instead of going to the thrift store to buy a tablespoon,” Riffenburgh explained. “They’re out there making a path, and it’s noisy, and everybody sees it. It’s clearly important to the organization because they’re blasting away, and things are happening.” One interesting finding, she said, was that the participating organizations were split almost equally into the two types, with only one or two somewhere between these

two types. She noted, however, that Brach conducted a similar study and found more of a continuum between these two types (Brach, 2017).

Riffenburgh then presented a composite case study involving Carol, a fictional health literacy leader. Carol has a “backhoe” at her disposal because the leaders of her organization have made health literacy a priority: they named an executive sponsor and champion, created a taskforce, ensured she has access to senior leaders, developed supportive policies and mandates, allocated resources, and created a health literacy office with organization-wide reach. As a result, Carol has been able to make widespread progress in spreading and embedding health literacy through the organization. When Riffenburgh asked one of the interviewees in this type of organization what it was like being the change leader, the person replied, “I’ve loved it. It’s significantly easier if leadership is on board. Without that, change is not likely.” In Riffenburgh’s opinion, that was an understatement because change is definitely not likely.

Jamie, another fictional health literacy leader, works in a “tablespoon” organization, where she has little or no leadership support, no sponsor, no resources, no mandates, and little access to leaders at any level. Health literacy is not a priority at her organization, and she is only allowed to work on it part time. She has managed to find some allies in her organization, but they are working mostly under the radar on small projects. Despite having little in the way of resources or help, she and her team of volunteers keep “digging with their tablespoons.” When Riffenburgh asked one of the interviewees in this type of organization what it was like being the health literacy change leader, the person replied, “We feel like our hands are tied. We don’t have a voice or the attention of leadership.” The contrast between the frustration this person expressed and the joy of the person working in the “backhoe” organization was profound in Riffenburgh’s opinion.

A second theme the research identified was the significance of who was bringing health literacy into an organization and where in the organizational structure they worked. If awareness of health literacy came from a senior leader who had heard about health literacy at a conference or from a colleague, for example, that person was in a position to start moving things, Riffenburgh said. In contrast, health literacy initiatives that started from the bottom up had a much harder time gaining traction. In many cases, they not only did not have adequate access to organizational leaders, but they could not even get the leadership’s attention. “Without awareness and access, it was difficult to build support, but with both of those in place, it was much easier,” said Riffenburgh.

Riffenburgh’s research showed that the location of health literacy initiatives within an organization was a third theme that seemed to influence the level of success. Health literacy initiatives placed where they would have organization-wide reach and authority, such as part of quality improve-

ment, patient experience, population health, or care coordination, were more successful than initiatives situated in one area or service line, such as in nursing education, the medical library, patient education, or marketing. “If the initiatives were under the chief quality officer or chief experience officer, things were going to be much easier,” said Riffenburgh. She added that being placed in a silo, such as under the chief nursing officer, made it easy for people in other parts of the organization to ignore health literacy. It was often seen as irrelevant to their work unless it was led by a leader with authority over their area or department.

The fourth theme identified in the study was the health literacy change leader’s level of experience within their organization. The research suggested that longevity in the position was a factor for success, as was the health literacy leader’s passion and commitment to keep going despite setbacks. “I would hear stories of incredible frustration, yet they were persistent. That was remarkable,” said Riffenburgh. She noted, however, that there was a “vast gap” between the background and training these individuals had and the demands of their job. It was not surprising that almost none of the health literacy leaders she spoke with had training in health literacy. However, it was surprising how little training they had in areas such as making persuasive presentations to senior leadership, catalyzing organizational change, and creating easy-to-read text-based information for their organizations.

The fifth theme that emerged related to how health literacy change leaders made the case for health literacy to their organization’s leadership. The majority of participants were unsure how to begin making the case. They described somewhat randomly choosing a strategy and trying it out. The strategies they most commonly tried included linking health literacy to other initiatives, focusing on cost savings and return on investment, presenting statistics on health literacy, and relaying stories of patient experiences to engage both the hearts and heads of organizational leaders. Of note, only one interviewee mentioned using important legal, regulatory, and compliance issues to justify addressing health literacy to leaders.

Based on her findings, Riffenburgh offered two sets of recommendations: one for the health literacy field and perhaps funders, and the other for health literacy change leaders. For the field, her first recommendation was to develop and implement strategies to increase health system leaders’ awareness of health literacy, perhaps by targeting the conferences they attend or the publications they read. The challenge is to learn how to make the case to health system leaders so they take the lead in starting health literacy initiatives. Her second recommendation to the field was to identify the most effective locations in an organization to establish health literacy initiatives and then develop best practice guidelines for health care organizations on locating their initiatives. Her third recommendation was for the field to produce one or two current films with patient stories highlighting

their experiences in health care, because the films used now are quite old. For health literacy change leaders, she recommended building their skills for leading organizational change by learning their organization’s change process. This might include talking to others who have had success at creating change both within and outside of the organization. She also recommended that they learn how to better make the case for health literacy, be persistent and patient, and, just as importantly, honor the struggle. Making organizational change takes time, she said, but it is the best struggle to be engaged in because it is so important.

A CASE STUDY: ADOPTING HEALTH LITERACY IN A HEALTH PLAN2

“Ultimately, getting any initiative adopted by an organization is about trust, and trust is a function of credibility, reliability, and intimacy,” said Carlson. “Do you believe the source? Is it credible? Consistent?” he asked. “When you have a conversation, when you interact, do you feel like they are actually engaging with you, or are they saying something they have been told to say or that is generic?” Earning and establishing trust unlocks the potential of technology to enable a more human experience. In short, said Carlson, trust begets engagement, and in the same way, health literacy equals engagement when it is done right. The unique thing about health care, he added, is that no matter what part of the health care system someone interacts with, the experience of health care is emotional, which makes establishing trust even more important.

Carlson noted that the technological aspects of how people interact with the health care system are getting more complex. Today, there is virtual care delivery and virtual service processes. Chatbots may be replying to questions online, but chatbots are not appropriate for all questions. When a man calls in and says in a flat tone that he just got out of the hospital and his wife just died and does not know what to do, responding to him with a chatbot is not the way to go. “We want somebody to listen to him, understand how unique his situation is, and then do whatever it takes to offer assistance,” said Carlson. Technology alone, he added, does not help when it comes to dealing with the complexity of health care. It can be a tremendous burden or tremendously enabling.

Turning to the value of a health literacy intervention from UnitedHealthcare’s perspective, Carlson explained that his organization

___________________

2 This section is based on the presentation by Chris Carlson, senior vice president for consumer and customer experience, UnitedHealthcare Shared Service Operations, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

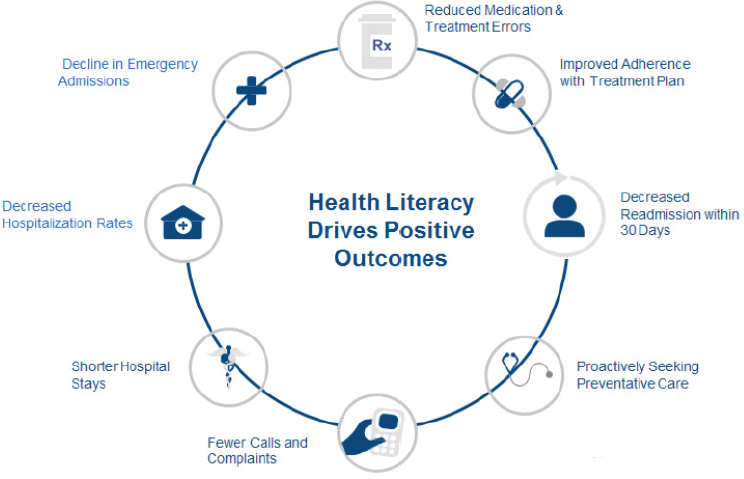

insures some 14 percent of the U.S. population. If the cost to the nation resulting from poor health literacy is $240 billion annually, UnitedHealthcare has the potential to save 14 percent of that total, or approximately $34 billion per year, if it could eliminate the waste resulting from inadequate health literacy (see Figure 5-1). That is money, said Carlson, that the company could use more effectively to improve the health system. The company’s internal research estimates that transforming a low health literacy community to a higher literacy level would affect medical costs, including an estimated 10 percent drop in emergency department visits and 18 percent decrease in hospitalizations.

As an example of the type of educational work his team does internally, he explained how UnitedHealthcare trains its pharmacy advisors who work with a Medicare population by putting them in real-life situations. “We give them big, thick cotton gloves and ask them to open a pill bottle, or we take glasses and scratch them, so you cannot really see through them and have them try to read the label on the pill bottle,” said Carlson. “That is the reality of the individuals they will talk to on the phone.” This type of approach puts people in the shoes of those they will be serving.

One of the first big transformations at UnitedHealthcare was its Advocate4Me initiative, which transformed how the company deliv-

SOURCE: As presented by Chris Carlson at Building the Case for Health Literacy: A Workshop on November 15, 2017.

ered health care services across roughly 30 million members in less than 18 months. The first steps in that initiative involved teaching everyone in the organization who answered the phone to listen. He and his team then built technology and analytic tools so that the person answering the phone listens actively and positively, thereby placing the conversation in context and engaging the caller. “If you do that, you can help keep people out of the emergency department and you may keep people out of the hospital,” said Carlson. Another component of that initiative improved adherence to treatment plans by offering clear directions in simple language both in direct conversation on the phone or in the service environment or via digital tools such as a mobile app or patient portal. These tools helped the company’s advocates talk to members using plain language, not the benefit structure language that exists in some health industry documents.

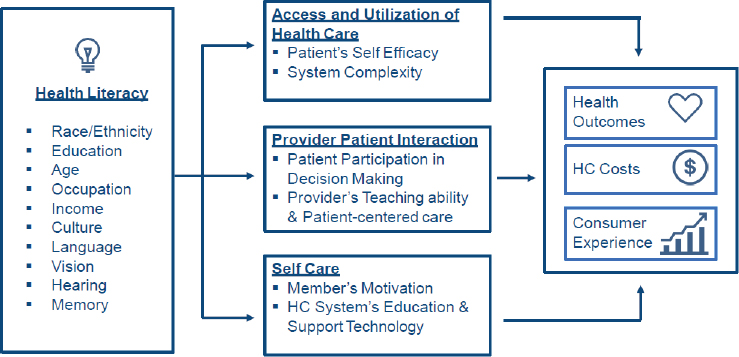

There are many things going on in a person’s world when calling in to a member advocate, logging onto the patient website, or using a mobile app (see Figure 5-2). Many individuals with chronic illness, for example, have comorbidities, depression, and other behavioral issues that affect their ability to comprehend information. In a health literate world, every individual gets to participate in the decision-making process and will feel empowered

NOTE: HC = health care.

SOURCES: Adapted from Paasche-Orlow and Wolf (2007), as presented by Chris Carlson at Building the Case for Health Literacy: A Workshop on November 15, 2017. Reprinted with permission from PNG Publications, publisher of American Journal of Health Behavior. Adaptation provided to Chris Carlson via personal communication with K. Ellingworth, K. Froeber, D. Goldstein, S. Kibler, and S. Tai, Optum Health, 2017.

to do so. They will have access to their own medical information, and they will come into their appointments having done some research and being prepared with questions. “That future state, I believe, is going to be accelerated by our ability to incorporate literacy and engagement tools into every interaction we have,” said Carlson.

Ultimately, though, patient motivation is critical for successfully engaging with the health care system, because if a person is not motivated to care for himself or herself, health literacy is irrelevant. However, Carlson noted, “If someone has been frustrated by a system that they do not understand, that is going to affect their motivation. That is a literacy issue, not a motivation issue.” In fact, when individuals feel there are barriers and complications that they cannot understand, they become demotivated.

For Carlson, there are two ways to look at the function of health literacy and engagement (see Figure 5-3). One way is through the interaction points an individual has on the journey through the health care system. When patients are “prospecting,” for example, they may be looking at the options covered by various health plans to fit their current life situation. “Onboarding” is when a new member registers for a plan or states their preferences, and Carlson said there are too few tools available to help members use their plans better. The other way to look at health literacy and engagement is through the patient’s entire ecosystem at home.

SOURCE: As presented by Chris Carlson at Building the Case for Health Literacy: A Workshop on November 15, 2017.

UnitedHealthcare’s approach of advancing health literacy has been to work on simplicity, accessibility, and developing understandable and relevant content that is actionable. “Consumers do not want to engage unless there is an action,” said Carlson. “Sometimes that action is to do nothing but stop worrying.” One area of focus has been on readability and relevance, and Carlson’s team developed a writer’s guide of internal language that he called the Blue Book, which lists 10 big ideas for creating clearer documents. They also developed an English-Spanish-Portuguese glossary and the Just Plain Clear scorecard. Other areas of focus included ensuring clarity on actions, using appropriate tone and personalization, employing simplicity in messaging, changing burdensome processes, working to minimize member anxiety during conversations, and listening when conversations do occur. This initiative, said Carlson, created a foundational set of change actions that got people in the organization galvanized to embrace health literacy as a necessity for driving the organization forward.

Carlson then listed a set of purposeful actions the company had taken since 2012 to build health literacy best practices and standards into every touchpoint and program across all business lines and functional areas. These included establishing a top-down approach to communication directed by a chief consumer officer. This effort includes rewriting every one of the company’s 3,700 templates, affecting more than 100 million touchpoints and eliminating those that were unnecessary. In 2017, for example, 690 templates were reworked and 44 were eliminated, producing a savings of $217,000. Carlson’s team created health literacy trainings that more than 200,000 UnitedHealthcare employees have taken, and the company established a center of excellence with professionally trained writers to support the company’s functional team. The Just Plain Clear tools were made publicly accessible and more than 150,000 people have accessed them in just the past year. Usage of the Just Plain Clear glossary, which currently has more than 12,000 terms, has tripled every year since the company published it, said Carlson, and people from 68 countries accessed this tool within 2017. The company, he added, tracks the top subjects, clinical, and nonclinical words that users search.

Service agents have been trained in spoken word health literacy and changing the way they listen to and talk with consumers to provide positive, clear, personal, and compassionate messages. Introduction of financial literacy practices are helping consumers understand cost and benefit options, including proactive alerts and personalized videos, and the company now solicits communication preferences to help address personal situations, such as the need for documents in large print or in alternate languages. “We took very deliberate and actionable steps to incorporate change, not just in what we did, but what we sent our consumers and our members,” said Carlson.

As an example, Carlson described what happened in 2012 when the DC Department of Health mandated that all health plans send every member who was a DC resident a letter about a preferred service to use when fulfilling HIV/AIDS-related prescriptions, regardless if there was an HIV diagnosis in the household. The letter had to (1) use wording provided by the federal regulators; (2) be on company letterhead; and (3) be signed by the chief executive officer or medical director. Of the more than 36,430 members who received the letter, about 15,300 telephoned the company’s service center wanting to know why they got this letter. Nearly 40 percent of the people who called had never called the service center before, while 54 percent called at least twice, and nearly 30 percent called three or more times. As evidenced by the content of the calls and the repeated phone calls from people who had never called before, the wording in the letters made them nervous that they were infected with HIV. “That costs money,” said Carlson. “Every time somebody calls us, it costs us $15 and it takes time out of the caller’s day.” Because of this incident, UnitedHealthcare has now instituted a health literacy control point and includes a plain language explanation via a cover letter, as well as a Web link to more information, that can help reduce member anxiety and increase understanding. The company also started an effort to help state partners and regulators become aware of how difficult content can be to understand and how it can affect its members adversely.

Another case study Carlson presented involved a survey of the company’s Medicare Part D and Medicare Advantage group members. This survey asked members how they felt about their understanding of the materials they received and their medications. Part D members who rated their understanding of their benefits from 0 to 4 called the service center three times more frequently than did those who rated their understanding between 9 and 10. That ratio was even higher among Medicare Advantage members. At $15 per call, there was a clear incentive for the company to rewrite its plan materials to reduce complexity and increase understandability. Carlson placed the estimated cost savings at $4 million or more annually for its Part D and Medicare Advantage populations.

In closing, Carlson said he wanted to underscore the importance of engagement and trust developed through a series of positive experiences that result from the simplicity, relevance, and actionable nature of the conversations between members and the company. Those conversations, he said, can be verbal, digital, and written. He referred to the people who received the HIV letter and noted how it was irrelevant to most of them, but sending it created relevance, which led to frustration, fear, confusion, and a struggle to understand; this produced anxiety and problems those individuals did not need. “At the end of the day, simple, clear, relevant, and focused conversations, digital or otherwise, is what it is all about,”

said Carlson. “Ultimately, engagement and trust are based on literacy and simplicity in the experiences we have with our consumers every day.”

A CASE STUDY: ADOPTING HEALTH LITERACY IN A PUBLIC HEALTH SYSTEM3

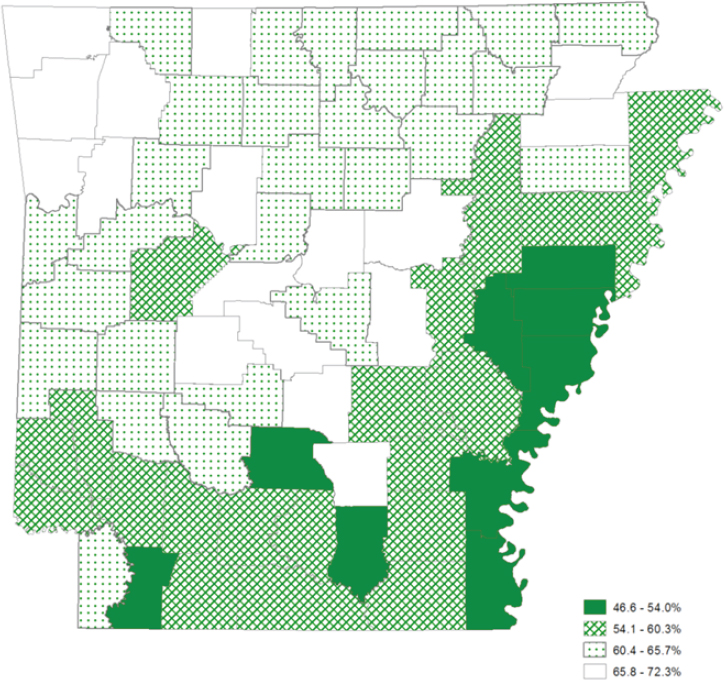

Arkansas, explained Dillaha, has a unified health department, which means the state agency she works for operates all 94 local health units in the state’s 75 counties. Almost 3 million people live in Arkansas, with 19 percent of the population living in poverty and 17 percent living with a disability. Only 14 percent of the state’s residents older than age 25 graduated college, and only 64 percent of the state’s households have a broadband Internet subscription, which is the second lowest in the nation. In addition, the state was 48 out of 50 states in the 2016 America’s Health ranking, and 37 percent of the state’s population—about 820,000 people—have low health literacy (see Figure 5-4). Dillaha noted that the counties with the lowest health literacy tend to have the lowest life expectancy in the state. She also explained that at least one-quarter of the population struggles with low health literacy even in counties with the highest level of health literacy.

Not long after Dillaha had read the 2004 Institute of Medicine report Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion (IOM, 2004)—which was her “Aha!” experience—she was appointed director of the Arkansas Department of Health’s (ADH’s) Center for Health Advancement and became aware that people in Arkansas struggled with grasping the information made available to them and using it to make decisions about their health. She and a local pediatrician who had gone through the American Medical Association’s health literacy training gave a joint presentation to the weekly grand rounds at the health department on health literacy. “You would have thought we had set off a bomb,” said Dillaha. “It resonated, and the ripple effects have continued even to this day.”

Dillaha and her colleagues at the health department spent the next couple of years talking about health literacy to everyone they knew, and on July 24, 2009, the ADH, Arkansas Literacy Councils, University of Arkansas Cooperative Extension, and Arkansas Children’s Hospital held a joint meeting to which they invited everyone they could find who was working on health literacy. Out of that meeting came the Partnership for Health Literacy in Arkansas, which became the health literacy section of the

___________________

3 This section is based on the presentation by Jennifer Dillaha, medical director for immunizations and medical advisory for health literacy and communication, Arkansas Department of Health, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

SOURCE: As presented by Jennifer Dillaha at Building the Case for Health Literacy: A Workshop on November 15, 2017.

Arkansas Public Health Association, a broad-based coalition of individuals, agencies, and organizations committed to improving health literacy among all Arkansans. The coalition has had its ups and downs over the years, said Dillaha, and it became somewhat dormant over the past few years, although it is now taking off again.

What the coalition discovered over time was that low health literacy is more than a literacy problem and that it cannot be solved with more health information. They also learned that individual patients are not the only ones with low health literacy—the health care system, including the public health system, has a health literacy problem, too. By 2011, when the ADH had developed a strategic plan there was a broad consensus within the agency to add strengthening and integrating health literacy strategies into

its overall plan for addressing high-burden health issues and strengthening and expanding the clinical services that it offered through its 94 local health units. Today, the health department’s 2016–2019 strategic plan infuses health literacy into every one of its goals on childhood obesity, teen pregnancy, mental and community wellness, hypertension, immunizations, and tobacco use. Every objective related to each of these goals now includes a health literacy component, Dillaha explained.

“This was made possible because we had support from the highest levels at the health department to make health literacy an important part of what we do,” said Dillaha, echoing what Riffenburgh and Carlson said about the importance of having support from the highest levels of an organization. In Arkansas’s case, the director of the Office of Health Communications (who has since retired) was an early participant in the partnership and an avid supporter of the health literacy strategy. At the time of the initial strategic plan, that office provided the staff support needed to address health literacy in the agency, although there were no staff dedicated to this effort. “All of the health literacy goals and interventions have been added on to what people have already been trying to do,” she said. “That adds to their workload, and sometimes we have competing priorities that caused health literacy and our capacity building to be put on the back burner.”

To build capacity, Dillaha and her colleagues started a plain language learning community. All four of the department’s centers, as well as the state laboratory and department administration, sent representatives, some of whom Dillaha refers to as the “voluntolds,” because they were volunteered by others to participate. “It is one of those things in an agency or an organization where you have some people who have a vision and understand it and others who are not quite there yet, and they struggle with why it is important,” she said. “That became the voluntold component.” However, all of the voluntolds had their “Aha!” moments, came to understand why health literacy was important, and were able to take that perspective and what they learned back to their part of the organization and encourage others to have that perspective.

This was such an important experience that even after the project ended in the spring of 2012, this group met with agency leadership and came up with some plans to implement more plain language. “That was what we really needed to take steps to integrate this with all that we were doing in the health department and that we needed ongoing training opportunities,” said Dillaha. The vision they developed was that people would rotate into the plain language learning community for 6 months, but making this happen proved challenging because of the struggle to get a funded position to oversee the learning community. However, reported Dillaha, the current director of the Office of Health Communication is supportive and now has funding to recruit and hire such a person.

The ADH did receive a grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Public Health Improvement Initiative to improve the communications that the department issues, including the state health assessment and health improvement plan the department published in 2013. This document, which identified Arkansas’s big health problems and how the department planned to solve them, was written using plain language principles and has been extremely popular, according to Dillaha. She noted that Nathaniel Smith, the department director and state health officer, has called this the most important document the health department produced over the past 5 years because it represents a paradigm shift in terms of serving as a model for what the state needs to do going forward. She added that in the past producing documents in plain language was challenging because many of the contributors were epidemiologists who did not have plain language skills. “We relied on our partner, the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences,” she explained. “They have helped with training, but we would like to develop in-house capacity to provide that training to our staff.”

The ADH has also received funding for several other projects, including one focused on maternal, infant, and early childhood home visiting that at its core is a health literacy intervention. Currently, the program serves 53 counties using one of five models implemented through the department’s local health units and partners. The idea behind these programs, said Dillaha, is to provide individually tailored, evidence-based education and information as well as resources and support to expectant parents and families. In a 2001 report, The Pew Charitable Trusts found that well-designed and implemented home visiting programs show a $5.70 return on investment for every taxpayer dollar that is used for these programs (PHVC, 2001).

One of the models, Baby Back Home, works on improving adherence to medical appointments and immunizations, facilitates coordination of health care, monitors a child’s growth and development, identifies local resources to meet the needs of the family and infants, and promotes parent education. “Does that sound like a health literacy intervention to you?” asked Dillaha. “It does to me.” For babies in this program who weighed less than 2,500 grams when they were born, the infant mortality rate has been 8 per 1,000 compared to the infant mortality rate of 52 per 1,000 for similar babies in the state who are not part of that program. In addition, for children from 0 to 18 months in this program, the immunization series completion rate is 94 percent, compared to approximately 50 percent for the state overall. Sisters United, a program developed by the ADH’s Office of Minority Health and Health Disparities and supported by the Region VI Southwest Regional Health Equity Council, is another successful infant mortality reduction program. Sisters United trains members of African American sororities to go into the communities and use health literacy

principles to talk to African American women about taking folic acid before they are pregnant, getting flu shots when they are pregnant, breastfeeding, and following safe sleep practices as a means of reducing infant mortality.

Dillaha said she did not have time in the presentation to do justice to the many activities the ADH has undertaken through its local health units. For example, the local health units have learned to use the teach-back method in the state’s HIV program, and the state’s Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program provides children’s books so parents can read to their children about some of the health lessons they are learning through the WIC program.

Dillaha concluded her presentation with some lessons learned. One lesson is that in terms of organizational capacity, increased awareness of low health literacy is not sufficient to improve health literacy. Awareness must be accompanied by increased capacity for addressing low health literacy. Another lesson is that efforts to change health behaviors that do not address health literacy will be confounded. Dillaha said she recognizes the ADH is not likely to get many additional resources to conduct health literacy activities, so efforts to improve health literacy must be implemented by using current resources differently. Perhaps the biggest challenge she has faced has been acquiring funding for staff with time dedicated to working on increasing health literacy capacity throughout the health department.

DISCUSSION

To begin the discussion, Brach commented that given the importance of leadership and remembering that leadership can change, it is critical to institutional health literacy practices to establish a health literacy infrastructure even in a “backhoe” organization because subsequent leadership may be less supportive. She also noted that just as there can be physician burnout, health literacy champion burnout is a concern in “tunnel and teaspoon” organizations. To help prevent champion burnout, Brach suggested that the International Health Literacy Association should consider developing a mentoring program to support those individuals. Riffenburgh noted that three of the champions she interviewed have left their positions in the past year because of burnout.

Brach then asked Carlson if there is a case for UnitedHealthcare to invest in full-time staff to engage in health literacy activities to reap the potential billions of dollars that the company could save. Carlson replied by clarifying that the $34 billion figure he cited represents potential value to members, which is different from savings. Having said that, he noted that Steven Rush, the director of the health literacy innovations program at the company, has full access to and is a consultant for his entire team, much of which focuses on simplicity, relevance, and engagement. He explained

that where he sits in the organization allows him to build and implement programs across the entire enterprise, whereas Rush sits in a policy-oriented part of the company. At UnitedHealthcare, it is his team’s job to provide Rush with enough capacity to create, administer, and direct policy and then leverage his group to build systems that make that policy real for consumers and for people in the organization.

Smith commented that he has seen many initiatives start in his health system and eventually fade away because they are not solving a problem that keeps company executives awake at night. Making that case, he said, requires metrics that correlate with something that concerns those executives. In that context, he asked Riffenburgh if any of the organizations she interacted with spent much energy producing robust, reliable metrics that answer questions important to organizational leadership. “Very few,” said Riffenburgh, even though there are multiple instruments that those organizations could be using. One issue for many “tunnel and teaspoon” organizations, she said, is that it is hard to know what the issues are that most concern leadership if there is no access to leadership. Carlson suggested focusing on loyalty measures, which are a concern for every health system today. His organization, for example, has spent the past 2 years focusing on net promoter score, a management tool that can be used to gauge the loyalty of a firm’s customer relationships. In his opinion, measuring health literacy itself is missing the mark because that is not the direct issue that concerns most health system leaders.

Michael Villaire from the Institute for Healthcare Advancement asked Riffenburgh how the health literacy leaders in “tunnel and teaspoon” organizations evaluated themselves and their activities to even maintain the little support they received from their health systems. Riffenburgh said that she did not delve into that issue in the limited time she had with the people she interviewed. She did observe that in low-support organizations, the expectations of the champions were unclear. “When the people above you do not really know what health literacy is, and you do not have a way to tell them, it is hard to figure out how your progress should be measured, or even what you or they are doing, or if the people above you even know or care what you should be doing,” she said. In those organizations, there was a great deal of “stabbing in the dark and just starting,” she explained, with no strategic plan. Rather, it was grabbing the low-hanging fruit of finding a document that could be revised to be easier to read. In fact, she added, one of her findings was that in “tunnel and teaspoon” organizations, the health literacy champions did not even know if there was an organizational change model in place, making it difficult to know what would be possible to accomplish in those organizations.

Linda Harris from the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion asked Carlson if UnitedHealthcare believes that the health literacy

work at the company, which includes the larger issue of improving customer experience, is something the company can use to increase market share and to promote and differentiate UnitedHealthcare from its competition. “Yes,” replied Carlson. “We feel strongly that our ability to engage will absolutely be a differentiator and create a distinctive relationship between our organization, our brand, and the members and the providers with whom we work. There is no doubt that we are spending time and resources to build foundational capabilities and a strategy around that specific focal point. It is our intention to differentiate on patient experience.”

Earnestine Willis from the Medical College of Wisconsin asked Riffenburgh if she had any insights into why placing health literacy in the nursing department resulted in it being siloed compared to putting it under quality improvement, which led to wider dissemination in an organization. Riffenburgh replied that those she interviewed said that it had to do with perception—when put under the director of nursing, the attitude at those organizations was that health literacy was only important to nurses, for example. In contrast, when placed in an area that everyone in the organization was supposed to pay attention to, such as quality improvement or patient experience, that sent a loud signal that health literacy was an organization-wide priority. That attitude might be different, she said, in a nurse-run organization, such as a magnet hospital. In fact, her professional experience before starting her doctoral program was that she worked in an organization dominated by nurses, and since her health literacy initiative was in a different area, the nurses were not interested, and she could not get any traction for her program.

Jennifer Pearce asked Carlson if UnitedHealthcare had plans to use health literacy interventions to bridge the divide between insurer and provider. Carlson replied that the plan is to extend their work outside of the company. “Our focus on experience and relationships inside the company is on its way outside with the consumer as well as with the provider,” he explained, saying:

We are starting to work with the provider systems across the country, globally actually, around experiential attributes, ease of information exchange between systems, elimination of processes that are required based on data we might already have, and simplifying everything we can do to automate and accelerate the access to care when it is required and certainly not create hassles and barriers based on complexity and challenges with literacy.

Helen Osborne from Health Literacy Consulting commented that the hospital she worked for 20 years ago did not even have a teaspoon, but more of a medicine dropper. In fact, the hospital president had no understanding or tolerance for any health literacy activities. The lesson she

learned was the importance of having an entrepreneurial spirit and seeking alternative paths to make a difference, often going outside an organization. Riffenburgh agreed that it is sometimes more effective to come from outside an organization because leaders often listen more carefully to outside voices. She then recounted that three of the people she interviewed from “tunnel and teaspoon” organizations said their organizational leaders had each called health literacy “fluff.” With leadership like that, it is not hard to see why people experience burnout, she added.

Ruth Parker from the Emory University School of Medicine commented that using health literacy to drive retention as an outcome makes good sense, and she asked Carlson how the company sees health literacy relating to consumer health activation and engagement, which could also be used to build the case for health literacy. Carlson said patient engagement is critically important to UnitedHealthcare and the organization uses a tool—the activation index—to measure it. In his view, if members do not understand, they will not adhere, and if they do not adhere, they will not engage and be activated. “Activation is a critical output and a function of interacting in a way that enables simplicity, relevance, action, and literacy,” he said. “I see a deliberate linkage between activation and literacy at the individual level.”

At the organizational level, he continued, the ability to engage and activate communities differently or provider delivery systems differently is critical to the overall health and well-being of the population, the family, and the individual. Many of his organization’s interventions are now focusing on activating the family unit as a means of providing more effective care for a family member. Carlson added that in his opinion, effective activation will strengthen and accelerate the case for democratizing the health care system, to which Parker added that democratization will not happen without health literacy.