2

Global Health and Governance of Public–Private Partnerships in the Current Context

The workshop opened with a presentation by Michael R. Reich from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health on the core roles of transparency and accountability in the governance of global health PPPs and was followed by a panel discussion on the challenges in PPP governance in global health. The four panelists—Steve Davis from PATH, Mark Dybul from the Georgetown University Center for Global Health and Quality, Muhammad Pate from Big Win Philanthropy, and Tachi Yamada from Frazier Healthcare Partners—discussed transparency and accountability as well as additional dimensions of PPP governance, board structure, terminology, power dynamics and equity, and the management of real and perceived conflicts of interest.

THE CORE ROLES OF TRANSPARENCY AND ACCOUNTABILITY IN THE GOVERNANCE OF GLOBAL HEALTH PUBLIC–PRIVATE PARTNERSHIPS

This section summarizes Michael R. Reich’s presentation based on the commissioned paper “The Core Roles of Transparency and Accountability in the Governance of Global Health PPPs” (see Appendix A) and the discussion that followed.

To begin, Reich provided the definition of a PPP for global health that has been used by the PPP Forum: PPPs are formal collaborative arrangements through which public and private parties share risks, responsibilities, and decision-making processes with the goal of collectively address-

SOURCE: As presented by Michael R. Reich on October 26, 2017.

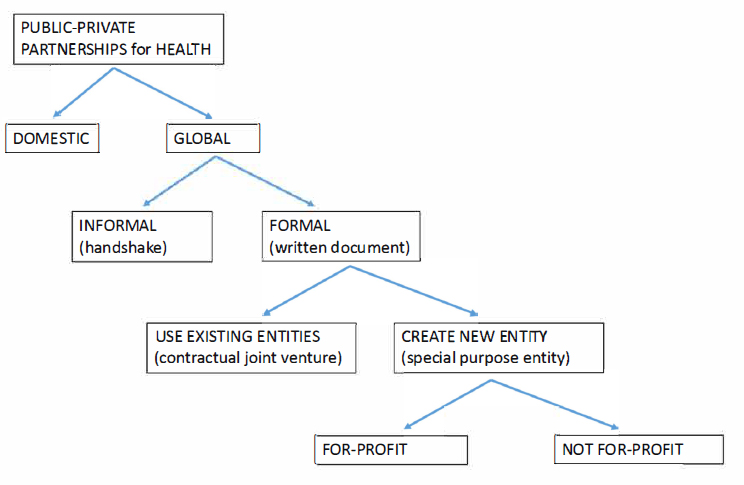

ing a shared objective within the global health field. A key point here, he said, is that PPPs involve a wide range of actors, stakeholders, and types of partnerships, and that different types of partnerships may require different governance structures, processes, and practices. Partnerships, said Reich, can be domestic or global, be informal and sealed with a handshake or formal and finalized with a signed document, use existing structures in a contractual joint venture or create a new special purpose entity, and be for profit or nonprofit (see Figure 2-1). He also noted that a single PPP can evolve from one type to another and engage different actors and stakeholders over its lifetime.

Governance is a relatively new term, said Reich, and as such it does not yet have a stable definition. To frame the workshop’s discussion, the PPP Forum borrowed the definition of governance as “the art of steering societies and organizations” from the Canadian Institute on Governance, which admits that the complexity of governance is difficult to capture in a simple definition.1 This is particularly true, Reich acknowledged, when dealing with global health PPPs given the multiple partners, languages, cultures, and expectations involved in these partnerships. He suggested

___________________

1 See https://iog.ca/what-is-governance (accessed January 19, 2018).

that governance of global health PPPs is less about steering a process and more akin to herding cats.

In preparation for the workshop, the National Academies Research Center provided Reich with a review of the literature on PPP governance. His initial impression after reading through 519 titles and abstracts and identifying 42 that were directly relevant was that the large volume of publications contained many recommendations, but there was little application of proposed models to real-life partnerships. He did, however, find within the literature two commonly discussed terms—transparency and accountability—and decided to focus on those concepts as separate and orthogonal dimensions of designing and evaluating PPPs.

Transparency and accountability are not simple concepts, acknowledged Reich. For example, a partnership might have low transparency to the public but high accountability to a specific group or entity, he explained. His proposed two-dimensional model does not specify how much transparency or accountability is good or desirable. Furthermore, these two dimensions represent only two of several possible aspects of governance. Some might claim, for instance, that participation should be considered as a third variable of governance, although Reich said that he preferred to view participation as a means to achieving transparency and accountability. Reich therefore decided to propose a simple two-dimensional model in order to help improve conceptual clarity about PPP governance and to provide a model that could lead to concrete options for planning, assessing, and changing PPP governance.

Within the dimension of transparency, Reich presented three relevant questions: who gets the information; what is the information (i.e., inputs, processes, outputs, and outcomes); and how does information dissemination occur. Transparency is important because it allows for learning, contributes to democracy, shapes organizational performance, and contributes to a positive public perception of the PPP. It also contributes to accountability: it is difficult to be held accountable if information on PPP performance is not available.

For accountability, Reich noted that the literature identifies two core elements: answerability and sanctions. His favored definition of accountability, from Edward Rubin (2005), is that accountability is “the ability of one actor to demand an explanation or justification of another actor for its actions and to reward or punish that second actor on the basis of its performance or its explanation.” As with transparency, Reich presented three relevant questions: to whom is the partnership accountable; what is the partnership accountable for in terms of metrics, processes, outputs, and outcomes; and in what way is the partnership held accountable? Accountability is important because it assures that a PPP is achieving its public interest objective; changes and improves organizational performance; con-

tributes to democracy; and contributes to a positive public perception of the PPP.

Using these two dimensions of transparency and accountability, Reich created a PPP governance matrix (see Table 2-1) that can serve both analytical and planning purposes. As an analytical tool, the matrix can help assess the characteristics and levels of transparency and accountability for an organization. As a planning tool, the matrix can help design transparency and accountability relationships and mechanisms for new PPPs.

The relationships described in this matrix led Reich to ask the ethical question of how much transparency and accountability should be

TABLE 2-1 PPP Governance Matrix: Assessing Transparency and Accountability for a Hypothetical PPP

| Relationship: Party B | Contents | Mechanisms | Level (High/Low) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information to? | Information on? | How informed? | ||

| Transparency: Party A (PPP) | General public | Limited number of outputs | Annual report available on PPP webpage | Low |

| Beneficiaries | Information on a few outputs | Written report and public meeting | Low | |

| Board of directors | Detailed reports on key inputs, processes, outputs | Board meetings, financial and operating reports | High | |

| Accountable to? | Accountable for? | How accountable? | ||

| Accountability: Party A (PPP) | General public | Limited number of metrics | PPP webpage, public hearings | Low |

| Beneficiaries | A few metrics on outputs | Ombudsman and complaints, using public pressure and reputation | Low | |

| Core partners | Detailed metrics on inputs, processes, outputs | Annual reviews of key staff, with firing or bonus, and of key partners | High |

NOTES: Contents include inputs, processes, and outputs. PPP = public–private partnership.

SOURCE: As presented by Michael R. Reich on October 26, 2017.

required. One reviewer of the matrix suggested that minimum standards could be set, while another raised the idea of creating bronze, silver, and gold levels to rank PPP governance. The more complicated questions, said Reich, are who decides on those standards and how. There are national laws, for example, that govern requirements for nonprofit organizations’ tax reporting and corporations’ regulatory filings. An international standards organization could set standards, or a self-regulatory PPP association could establish good partnership best practices. He observed that, in the current environment, PPPs are left to set up their own standards.

Reich noted that, within a partnership, different stakeholders or partners may demand different levels of transparency and accountability, which raises the question of how to align those different interests and how to deal with the “multiple accountability disorder” that such disagreements can create (Ebrahim et al., 2014) while seeking to achieve the goals of the PPP. One of the tangible questions for PPP governance is what happens when partners disagree. Reich’s impression is that partnerships work best when there are relationships of trust between the core partners. “It is those relationships of trust that are underappreciated in the field of public health and their role both in policy making and in making organizations work well,” said Reich.

In closing, Reich said he hoped that his paper helps clarify what governance means for partnerships and that the matrix of transparency and accountability as two core dimensions would prove useful in helping partnerships organize their governance structures and strategies.

Responding to a question from Jo Ivey Boufford from New York University about why he chose not to include inclusiveness and engagement as part of his matrix, given issues with power relationships in PPPs, Reich noted the decision-making problem with whom and how many to include in the governance structure. He suggested that too many representatives on a board can make it difficult for the board to serve its strategic functions, and in a sense, the board becomes more of a representation assembly rather than the supervisor of transparency and accountability. In addition, he added, total transparency to all stakeholders is a difficult goal to achieve given that the board will need to make certain decisions based on sensitive information to which not everyone should have access. “This gets down to questions of what kind of information should be available and to which groups,” said Reich. “If you want serious discussions of sensitive information, it is difficult to do it with representatives from all the groups sitting at the table.”

ADDRESSING MAJOR CHALLENGES IN THE GOVERNANCE OF GLOBAL HEALTH PUBLIC–PRIVATE PARTNERSHIPS

In her introduction of the four panelists, session moderator Regina Rabinovich shared that in conversations with them before the workshop, she discovered that each was “looking at different parts of the elephant based on their various experiences.” Given the diversity of their experiences, she asked the four panelists to talk about the major challenges they encountered in governing global health PPPs based on the partnerships in which they have engaged and examples of how they worked to manage them.

Steve Davis remarked that many global health partnerships today are developing as one-off activities that bring together public-, private-, and social-sector partners for a specific project. These partnerships are not intended to have sustained continuous life cycles that characterize some of the largest partnerships for global health; however, they still require effective governance structures. Based on his observations and experience engaging in these partnerships from the social-sector side,2 Davis made an appeal for the global health field to stop using the term public–private partnership. “First of all, it is old and outdated,” he said, “and second, most of these [collaborations] need to be thought of as multisector, and PPP leaves out the whole idea of where the social sector fits in.” In addition, he said, it has been shown that most industry–government partnerships do not function to their greatest potential unless they include a social-sector partner. For Davis, the term multisector partnerships reframes the conversation and brings different sectors to the table from the beginning.

Going forward, Davis predicted there will be an increase in the types of mechanisms used to create partnerships; however, literature demonstrating the effectiveness of emerging forms of partnership is lacking. “We have some real work to do in the next few years to make sure that as these grow, their effectiveness grows,” said Davis.

On transparency and accountability, Davis agreed with Reich’s position that both are key dimensions in the success of multisector partnerships. He emphasized that more details are needed about who should be accountable for what and transparent about what. In addition to transparency and accountability, Davis proposed three more dimensions that are important for governance. First is altitude, as in at what altitude is the steering committee or advisory board being asked to operate compared to the partnership’s management. The second is alignment around the objective. Successful partnerships, said Davis, have a clear objective and

___________________

2 Davis defined the social sector to include philanthropic, nongovernmental, and academic actors.

are usually well resourced to achieve that objective. The third added dimension is adaptability.

Mark Dybul began his remarks by agreeing with Davis that the term PPP is outdated in the current global context. From a philosophical perspective, he said, it is important to examine the 2002 Monterrey Consensus,3 which set the path for the two largest partnerships in global health—the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (Global Fund), and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance (Gavi). The Monterrey Consensus focused on several principles: country ownership, results-based financing, accountability and transparency, and multisector involvement. Dybul noted that the negotiations to produce the Monterrey Consensus almost broke down over the inclusion of the private sector.

Turning to the governance of the Global Fund and Gavi, Dybul explained that the structures established to govern them are not boards but rather parliamentary or congressional structures. These governing bodies exist for a number of reasons, and a primary one is to raise money. One of the reasons that these two partnerships have succeeded is the strong support they have received from civil society as well as from the public and private sectors, and that support has come, at least in part, because the parliamentary structure allows all sectors to be involved. Yet, one downside of this structure has been around accountability and transparency, Dybul shared. Another has been the challenges associated with deciding on membership and voting privileges.

The Global Fund’s parliamentary body includes 10 voting seats for implementers; 10 for external funders, including industry; and 20 alternates plus nonvoting members. The number of seats for external funders is based on the amount of money an entity provides, with industry holding one of the seats. When the governance structure was established, the expected role of the governing body’s members was unclear. “Constituencies for a long time have come strictly to represent their constituency and vote according to their constituency and their constituencies’ desires, rather than saying this is what our constituency thinks, but when you vote you have to vote in the context of what is best for the organization or structure,” said Dybul. Dybul advises newly forming PPPs to be careful and clear about membership requirements and expectations.

The Global Fund’s voting structure has proven to be problematic because it created two voting blocs—the funder bloc and implementer bloc—as if they were in competition, said Dybul. He continued, “this immediately tells people you are not trying to get to a common goal.” An additional challenge is the provision in the governance agreement that

___________________

3 See https://www.un.org/esa/ffd/monterrey/MonterreyConsensus.pdf (accessed January 24, 2018).

any four members of the funder or implementer blocs can vote no to bar a decision. The problem, he said, is that once this voting provision was established, it cannot be changed because the blocking minority votes against it. Dybul explained that one consequence is that the Global Fund is stuck with an antiquated voting structure that prevents the inclusion of new partners. “The world has changed in 15 years,” said Dybul. “There are big countries creating big development structures, and we cannot bring them onto the board. If you cannot be on the board and you cannot vote, why would you give money or engage with an institution?”

Moving from the institutional governance of the Global Fund, Dybul emphasized that in many respects, the in-country mechanisms of a partnership are more important than its global structure. The country coordinating mechanisms that were developed as part of the Global Fund have not worked well in many countries because of government dominance and difficulty engaging civil society at the country level, he suggested. “We are still not good at the country ownership principle,” said Dybul in his concluding remarks. “We need to focus on what is happening in the countries as much as on what is happening in the central structures.”

Muhammad Pate joined with Dybul and Davis in suggesting that the term PPP be retired given the preponderance of multisector partnerships today. Also problematic, he said, is the perception of governance in global health as hierarchical sets of institutions. “What we have in reality is networks of institutions and individuals with formal relationships and informal relationships,” said Pate. Governing in the context of networks operating in global health requires different structures than those that govern top-down partnerships.

Complicating this operating environment are the differences in worldviews of some members of the external funding community, Pate noted. China, for example, may have a different worldview than the United States or Europe about country ownership. In the same way, he explained, agendas and values can differ, making it challenging to align interests of the global PPPs and the countries where they are operating. “That divergence between supranational partnerships and the way they are governed, and the national governance arrangement . . . is a very fundamental issue that may explain some of the disconnect that you see,” said Pate.

He emphasized that asymmetries exist in the way some governance arrangements are configured, particularly regarding legitimacy. State and federal governments are the legitimate authorities in their own respective spaces; however, there may be other entities linked to global partnerships that do not have the same legitimacy and may not be accountable at the local level. In addition, there are asymmetries in information, finance, and influence that should be acknowledged when structuring governance arrangements for partnerships in global health, said Pate.

Reflecting on Reich’s matrix, Pate observed that the ethical dimension is missing. Public health has ethical principles derived from medicine, but Pate worries that the diverse group of actors in global health may not share those ethical principles. One effective multisector partnership that he feels does share these principles is the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI). The GPEI partners have been able to come together and steer the world toward nearly eradicating polio. Pate noted that within GPEI, each partner’s role and the role of the monitoring board were well defined.

On the other hand, the global response to the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa was “a miss,” said Pate. Across the many partners in this effort, none were held accountable for the failed response to the outbreak and the resulting loss of lives. “There were many local nongovernmental entities and national and regional governmental entities that played a role, but where is the accountability?” asked Pate. “We need more work in terms of accountability to the local entities.”

The final panelist Tachi Yamada focused his remarks on experiences and observations regarding board structures for PPPs. When he joined the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, he encountered partnerships and other entities with boards composed primarily of largely self-interested individuals with no sense of accountability for the overall welfare of the organization. In addition, many boards were too big to make substantial and wise decisions on behalf of the entities they represented. He also observed the tendency of boards to usurp the role of management in deciding what programs to support or decline. One of his biggest surprises was that the Gates Foundation did not have a board seat within many of these partnerships despite often being the largest funder.

Yamada said the term PPP describes a clash of two cultures with different expectations. Understanding these differences can help create better governance structures. Boards in the private sector have three straightforward responsibilities: fiduciary, strategy, and selecting the chief executive officer (CEO). Boards do not interfere with management; instead, management is delegated to the authority that runs the organization and makes day-to-day decisions. In the public sector, there is an additional responsibility to ensure that a program is meeting public needs, and Yamada emphasized that this responsibility is different from the role of a private-sector governing board. The board of a private-sector company recognizes that the company cannot survive if it fails to meet the needs of its customers; however, he explained, shareholders, not customers, drive the board’s decisions. A PPP board, on the other hand, is accountable to its customers, who are defined as the public. “Ultimately, we have to think of governance as not being controllers but people who are invested in the best interests of the entity that they are working with,” said Yamada.

He concluded his remarks with an example of a governance structure that he helped create 6 years earlier for the Global Health Innovative Technology (GHIT) Fund (the GHIT Fund is described in greater detail in Chapter 4). The tiered governance structure of the GHIT Fund has different components, each with specific roles and responsibilities. A council, whose only job is to select the board chair, is made up of funders. The board consists of independent experts, none of whom are funders or funder representatives. There is an advisory board of individuals appointed because of their expertise on relevant subjects and who have some representational connections, and a selection committee of domain experts who select the grant applications to approve and fund. “It is possible to create a structure in which different pieces have different functions, and maybe that is how best to bridge this gap in culture between the public and private sector,” said Yamada.

DISCUSSION

Rabinovich asked the panelists to address a governance issue that the PPP Forum members often encounter: managing conflict of interest when it involves industry partners. Yamada responded that in general, conflicts are acceptable as long as they are declared. Dybul added that most other individuals on boards have far more significant conflicts than the industry representatives. Grantees, whether from civil society, implementing governments, or funders, are all conflicted. He agreed with Yamada that disclosure and transparency are critical. Davis agreed with Dybul, and noted that in the private sector, board members often have conflicts and they sit on the board because they bring expertise that benefits the company. The solution, he suggested, is to disclose and recuse on conflicted matters.

Kevin Etter from the United Parcel Service (UPS) Foundation commented that in addition to retiring the phrase PPP, there is a need to change perceptions about private-sector engagement. He has found that there is an expectation for the private sector to change the way it engages with the public sector and civil society but an unwillingness for the public sector and civil society to change the way they interact with the private companies. “Change the conversation entirely and quit talking about private-sector engagement and start talking about public-sector engagement and civil society engagement and what it is that has to change in all sectors,” said Etter.

Sonal Mehta from Avahan and the India HIV/AIDS Alliance commented that while NGOs are expected to be transparent and accountable in a partnership, there is often little discussion about government accountability. Yamada replied that government accountability is very important, and one issue he has encountered is government being a pas-

sive partner rather than an active participant that contributes resources and commits to the success of a PPP.

“The lack of government engagement is often a two-sided problem,” said Yamada. “The first is that the PPP does not think about how the government could engage and take over a project. Second, they do not think enough about how to provide the funding to initiate that effort. On the government’s side, these programs are fine as long as they are funded, but there is no sense that the programs are important enough to put its own money behind it.” In his opinion, PPPs need to have a strategy to engage governments in their projects. Dinesh Arora from the National Institution for Transforming India commented that government agencies may not be equipped legally or financially to engage with the private sector.

Yamada noted the importance of legitimacy as a partner. He joined the Gates Foundation about 4 years after it started, and he discovered that, “like the nouveau riche investment banker that moved into the neighborhood and built this huge home, everybody hated us because we had no legitimacy.” His approach was to form partnerships with seven leading global organizations, including the World Health Organization (WHO), UNICEF, U.S. Agency for International Development, and the Global Fund, which had their own legitimacy, and the Gates Foundation could provide legitimacy through funding. In the end, WHO became the Gates Foundation’s largest grantee and the funds it provided gave WHO the flexibility it needed to implement a number of its programs. This arrangement situated the foundation as a partner rather than just a funder. In Pate’s opinion, the best multisectoral partnerships are those that have a diversity of values that individuals bring to the table, and that acknowledging the various sources of legitimacy, whether through providing financing, technical expertise, or political legitimacy, will level the playing field. He noted, too, the importance of developing a common language among partners from various sectors.

Davis said there is a need to work on multidimensional engagement models that help get rid of the presumptions about how each sector behaves, such as assumptions that the NGO sector can be inefficient, the public sector can be lazy, and the private sector can be greedy. He suggested building a cohort of individuals with experience in all three sectors who could bridge the various sectors and help reduce, although not eliminate, asymmetry and help structure governance to deal with inherent power imbalances. Davis also emphasized the need to stop treating the partners who provide funding to a partnership as customers who need to be pleased. The real customers, he said, are national governments, health ministers, health systems, and the people on the ground who are trying to improve quality of life. This change in attitude, he said, would

also help reduce asymmetries, as would building trust among partners and recognizing and understanding the important role each partner plays.

Sir George Alleyne from the Pan American Health Organization wondered if accountability could be viewed through a principal–agent relationship in which there is a relationship between the person who has the account and the person who renders the account, and in which transparency is not just another method of ensuring that information asymmetry is reduced to a minimum.

Reich concluded the discussion period with several comments. Addressing the issue of changing the terms used to describe public–private partnerships in global health, Reich said that PPP has become a brand name covering a wide range of organizations. He recommended against renaming these organizations as “multisectoral partnerships.” A more useful term might be “hybrid partnerships,” because there is literature on hybrid organizations that addresses social enterprise.

Reich appreciated Dybul’s point on the difficulty of changing a system of rules once it is in place, noting that institutional arrangements are “sticky.” According to the concept of path dependency, positive feedback loops frequently develop, which makes changing an institution or a policy once it is established difficult. “The lesson here is be careful what you set up at the beginning, when you have limited information on the effects of particular decisions, because it can have longstanding unanticipated consequences,” said Reich. He also agreed with Pate’s point about networks of institutions; Reich noted that many partnerships are a collection of organizational entities, each with their own set of rules and cultures that can clash.