Appendix A

Commissioned Paper: The Core Roles of Transparency and Accountability in the Governance of Global Health PPPs

By Michael R. Reich

Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health

(Email: michael_reich@harvard.edu)

Prepared for the Forum on Public–Private Partnerships

for Global Health and Safety

Exploring Partnership Governance in Global Health: A Workshop

October 26, 2017

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine

Washington, DC

Over the past two decades, the field of public–private partnerships (PPPs) in health has expanded enormously, both in the number of such organizations and in the study of this phenomenon. This growth reflects rising societal expectations about what partnerships can and should do to contribute to social welfare. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s Forum on Public–Private Partnerships for Global Health and Safety (PPP Forum) reflects this growth in interest in PPPs and has contributed to better understanding what these organizations do and how they contribute to society. Within this sphere, the question of “governance” of PPPs remains an important topic for additional analysis and discussion.

This paper was prepared as background for the National Academies workshop to examine “the evolution and trends in the governance of global health PPPs,” and provide “reflections on significant issues and current challenges with these governance structures, processes, and practices.”1 The PPP Forum staff suggested that I draw on my own work in considering the trends and challenges for PPP governance. Over the past two decades, I have had multiple engagements with PPPs in public

health. I have studied various partnerships2–5 and helped establish and oversee (as a board member) a new PPP. In April 2000, I organized a conference in Boston to examine PPPs and subsequently published a book based on that meeting with several case studies and analytical chapters.6 Many of the issues raised in 2000 persist today. In some ways it is comforting that the book could identify core challenges for global health PPPs 17 years ago. In other ways it is discouraging that certain major problems persist, especially related to governance, perhaps reflecting fundamental challenges in getting public and private organizations to work together effectively.

Diverse engagements with PPPs in global health over many years have highlighted for me the importance of transparency and accountability in partnership governance. In this paper, I first briefly review the literature on PPP governance. I then propose a simplified model of governance, with a focus on transparency and accountability, and discuss the implications of this model for assessing the governance of PPPs in global health and for designing the governance of a new PPP.

THE LITERATURE ON PPP GOVERNANCE

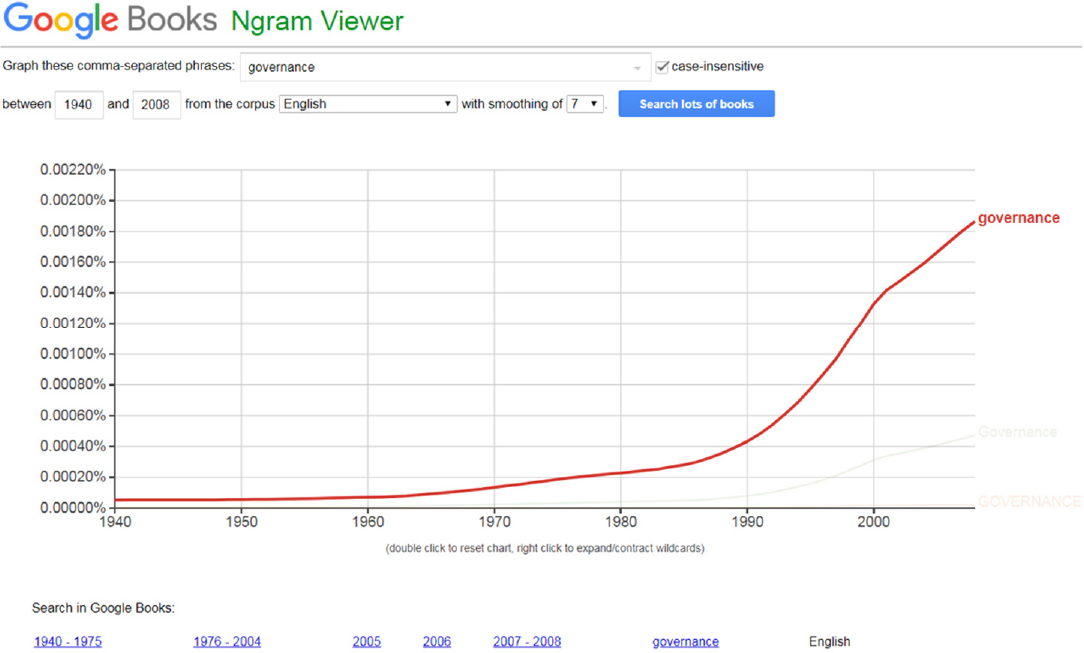

The first question is: “What do we mean by governance?” The National Academies invitation to the workshop gave a brief answer, defining governance as “the art of steering societies and organizations.” The source of this definition is the Institute on Governance, a not-for-profit public interest institution based in Canada (an interesting choice for the U.S.-based National Academies).7 This definition is useful in its emphasis on governance as an “art” form—something that involves both creativity and execution—and its goal of seeking to “steer” both societies and organizations, which implies knowing the course that the organization is expected to follow. The term governance is a relatively recent word, as shown by a Google graph of usage that demonstrates an impressive surge in the past two decades (see Figure A-1).

But as the workshop invitation also noted, definitions of governance are “varied”—an understatement. Even the Institute on Governance recognizes the limitations of the steering metaphor7:

Some observers criticize this definition as being too simple. Steering suggests that governance is a straightforward process, akin to a steersman in a boat. These critics assert that governance is neither simple nor neat—by nature it may be messy, tentative, unpredictable, and fluid. Governance is complicated by the fact that it involves multiple actors, not a single helmsman.

The ambiguity in definition and understanding of governance is heightened when applied to PPPs, precisely because these organizations are partnerships and do not fit neatly into the accepted categories of “public” or “private” organizations, businesses, or agencies. In addition, partnerships often involve multiple partners with no single “owner” or governor. The nature of partnerships creates both strengths and weaknesses for PPPs. As I wrote previously, “both public and private actors are being driven towards each other, with some amount of uneasiness, in order to accomplish common or overlapping objectives” in situations where “neither public nor private organizations are capable of resolving such problems on their own.”8

These endeavors thus bring together organizations with strikingly different cultures—“different values, interests, and worldviews”—to a space where “the rules of the game for public–private partnerships are fluid and ambiguous.”8 These cross-sector collaborations between public entities and private entities are complicated and time consuming because societies lack adequate standards or norms about how these new organizations should work (compared to collaborations between only private or only public entities). As a result, each PPP typically needs to invent de novo how it will operate and be governed.

In planning for this meeting, the National Academies staff conducted an initial literature review of PPP governance. The annotated bibliography on “partnership governance in global health”9 listed 27 documents published since 2000, including peer-reviewed articles, conference reports, consultancy reports, and books, with analyses of single organizations and comparisons of multiple partnerships. Many of the documents adopt a tone commonly found in the business management literature (sold in airports) on how to make your partnership work better. One report10 provides “five characteristics of successful PPPs.”a Another publication—based on a review of the “governance structures” of 100 global health partnerships—identifies the “seven habits of highly effective global public–private health partnerships,”11 specifying seven contributions and seven unhealthy habits, followed by seven actions to improve their habits.b Another article concludes that the governance structure of a partnership is a key determinant of success, according to an analysis of the voting rights of different parties in organizational boards.12

My initial impression of the literature on PPP governance, based on this review, was of a field characterized by a plethora of recommendations and an ambiguity of actions. The number of publications about PPP governance has undoubtedly grown, but it was difficult for me to identify any evolution or trends in the literature. I was impressed by the increased volume, but did not see increased clarity. One review of the “governance of new global partnerships” identified a series of interesting challenges, weaknesses, and

lessons from 11 partnership assessments, but did not specify a model for PPP governance and focused exclusively on the role of boards.13 (One conclusion of this study was that many PPP boards were designed to allow the participation of multiple constituencies, which reduced the ability to function as accountability mechanisms; to assure representation of many stakeholders, board meetings included 40 to 50 people, making it difficult to have in-depth discussions and resolve complex problems.) These reflections on PPP governance led me to think about an alternative approach focused on the concepts of transparency and accountability.

Following this initial review, the National Academies research center conducted a more detailed literature scan on partnership governance of three databases (OVID, Scopus, and Web of Science) for materials published since 2000.14 The search included the terms partnerships and global health and transparency, accountability, and governance in various combinations. The search also examined the publications of 14 global health organizations. The search produced a total of 519 titles and abstracts. A review of these 519 summaries found 42 that were directly relevant, 268 that were of some relevance, and 209 that were not appropriate. (The full search document of 166 pages is available from the author.)c

It is worth noting that the broader literature on “governance of health systems” has also grown significantly in recent years. A systematic review of “frameworks to assess health systems governance” between 1994 and 2016 found 16 different frameworks in the literature.15 The frameworks were based on various theoretical approaches in new institutional economics, political science, public management, and development. But this review also found that only 5 of the 16 frameworks have been applied. The authors concluded that the existing frameworks need to be tested and validated in order to understand “which frameworks work well in which settings.” They also emphasized that “health system governance is complex and difficult to assess” and that “[t]here is no single, agreed framework that can serve all purposes.”15

Based on this situation, it seemed to me that it would be more useful to focus on a higher-level model for PPP governance in hopes that it could be applied. I have adopted that approach in this paper. My goal was to create a model of governance that could simplify the complex challenges of PPP governance, and that could be applied by implementers and analysts involved in the design, assessment, and revision of how actual partnerships work in practice.

A SIMPLIFIED MODEL OF PPP GOVERNANCE

My approach envisions PPP governance as consisting of two key dimensions: transparency and accountability. These dimensions are oper-

ationalized through various measures and mechanisms, which I discuss below. I begin with a focus on clarifying these two dimensions, which are among the most widely discussed concepts in writing about governance. As Jonathan Fox notes, “a wide range of actors agree that transparency and accountability are key to all manner of ‘good governance.’”16 These two concepts also appeared as common themes in the NASEM literature scan on PPP governance.9,14

Many analyses of organizational governance consider transparency and accountability as part of the same category.16,17 For example, the authors of an analysis of the Medicines Transparency Alliance wrote, “Transparency is a necessary but not sufficient condition of accountability.”18 In this paper, I take a different approach. Instead of seeing one concept as a condition of the other, one inside the other, or one leading to the other, I consider transparency and accountability as orthogonal (and independent) dimensions of organizational governance (see Figure A-2). This approach takes one step beyond what Fox does when he considers transparency and accountability as parallel concepts and examines their overlaps and “uncertain relationship.”16

TABLE A-1 Two-by-Two Table of Low and High Levels of Transparency and Accountability

| Low Accountability | High Accountability | |

|---|---|---|

| High Transparency | High T, Low A | High T, High A |

| Low Transparency | Low T, Low A | Low T, High A |

By viewing transparency and accountability as separate orthogonal dimensions of governance, one can then think about organizations with high and low transparency and high and low accountability, leading to a two-by-two table of governance (see Table A-1).

Let me underline two caveats about this simplified model. First, I am not asserting that these two dimensions represent all possible aspects of governance for PPPs. The proposal is not intended as a grand theory of governance; instead, it is a “simplified” model. I argue that transparency and accountability are two core components of governance, and that these two dimensions can be used for planning new partnerships and for assessing and improving the operations of existing partnerships. Other dimensions no doubt could be included—for example, participation (or civil society engagement) is sometimes proposed as a separate aspect of governance.19 I prefer, instead, to see participation as a mechanism for expanding transparency and/or assuring accountability.d For the purposes of thinking about PPP governance, however, I suggest that these two dimensions provide improved conceptual clarity and operational implications. In addition, and most importantly, improved transparency and improved accountability may lead to improved performance by the partnership in achieving its organizational and societal goals. We should care about these two dimensions of governance because they can influence the partnership’s impacts on society, as I discuss below.

My second caveat is that this simplified model does not tell us how much transparency or accountability is good or desirable. This normative question about the level of governance (along these two dimensions) has to be provided through other social processes. Partners and stakeholders may disagree about how much transparency they want for a particular partnership, and they may also disagree about how much accountability, and to whom, is desirable. Our ethical intuition would probably tell us that the lower-left quadrant, with low transparency and low accountability, is not desirable for a PPP, since this would probably contribute to lower social benefits from the partnership. Our intuition would probably point to somewhere in the upper-right quadrant as desirable, although how far along each axis (and for which stakeholders) would be debatable

and contested. Indeed, it is this intuition, I would suggest, that brought both practitioners and researchers to the National Academies workshop on PPP governance. Understanding how to move an organization along these dimensions of governance, then, is critical.

This simplified model of a two-by-two table does not, by any means, solve the complex problems of governance of PPPs (or any other organizations) or address the many factors that contribute to the success or failure of a partnership. The format does, however, allow one to think systematically about the definitions (and purposes) of transparency and accountability, the ways to measure high and low levels for both concepts, different institutional mechanisms that can change the levels of transparency or accountability, and, eventually, how these two dimensions influence the performance of a partnership. In short, this simplified model is intended to create conceptual clarity about the purposes of PPP governance and also lead to concrete options for action to promote ethical and effective governance of PPPs in global health. Let us, therefore, consider these two dimensions of governance in more detail.

TRANSPARENCY

Transparency fundamentally involves questions of contents and relationships: What information is available to whom? In addition, transparency involves questions about the quality of the information and the mechanisms for making the information available.

Let’s start with the relationship aspect of transparency. This addresses the question of who has access to information from the partnership. The receivers of information can include the core founding partners, nonfounding and noncore partners, stakeholders who are not partners (such as beneficiaries), government agencies (including contracting agencies and regulatory agencies), relevant actors in the public health field, donor agencies, academics, and the general public. Depending on national law, partnerships can be required to make certain information available to specific government agencies and to the general public. For example, in the United States, partnerships that register as nonprofit and tax-exempt charitable organizations (as a 501(c)(3) organization) are required to file a financial report (Form 990) with the Internal Revenue Service each year, thereby providing information to the U.S. government. In addition, these organizations are required to make the annual Form 990 available for inspection to the general public during business hours (and many place the forms on their website for free download). National law and government policy (including memoranda of understanding with a PPP) can thus specify which information is to be made available to whom.

Most informational relationships are decided at the discretion of the

partnership (or at the direction of a partner in a written agreement to initiate the collaboration).e For instance, detailed information about salaries of executives and managers at a partnership may be available to the core partners on the board of directors but may not be available to the broader public or the beneficiaries of a PPP. Similarly, contracts with suppliers may be reviewed by the core partners but not by noncore partners. Indeed, the funders of partnerships can exert high degrees of influence over what is made transparent to whom, sometimes restricting access to information and sometimes expanding it. This pattern illustrates that not all partners are equal.

Next, let’s consider kinds of information. One way to think about kinds of information for a PPP is around inputs, processes, outputs, and outcomes. This typology is proposed by Reynaers and Grimmelikhuijsen (2015) in their article on transparency in PPPs,20 although I have slightly altered the definitions to fit with standard terms used in evaluation and management literature. Inputs could include the contributions from each partner, such as finances and sources of funding, materials purchased and received by the organization, and people who work at the PPP (human resources), as well as any intellectual property and information used by the partnership. Processes could include ways of making decisions (including plans and budgets) and related documentation such as agreements signed by the partnership, policy memos and analyses, minutes from internal meetings, expenditures by the PPP (financial reporting), and operational and strategic decisions for the PPP. Outputs could include who receives products managed by the PPP, and data sets that measure performance of the organization (in terms of relevant metrics or targets, or related to the partnership’s mission), such as numbers of beneficiaries, services delivered, or medications received, as well as lessons learned that others can apply. Outcomes would specify the ultimate performance objectives in terms of improved health status, client satisfaction, or financial risk protection.21 In their analysis of four partnerships in the Netherlands, Reynaers and Grimmelikhuijsen found that there was limited attention given to inputs and processes, and that most of the attention focused on outputs, but that the output targets were not always clearly specified and thereby created problems.20

The quality and scope of information is also often decided by the partnership. For instance, monitoring information on outputs produced by the PPP is often published in an annual report and made available to the general public. But these documents rarely contain any negative information and usually do not compare performance to targets or expectations. The full data set is not usually publicly available, or the data may be aggregated in ways that mask key results that could be viewed negatively, such as distributional issues (across regions or across income groups).

Another possibility is that raw data are provided, but in ways that are either not easily understood by people who are not technical analysts or not able to be readily analyzed. The presentation of data thus can shape whether the information is intelligible to different audiences.

The final consideration is mechanisms for assuring transparency. Four general types of mechanisms to promote access to information (and transparency) exist18: (1) access through public dissemination, where information is provided by the organization in publications or on websites, or made available in public reading rooms; (2) access by request, either as required by law (or lawsuit) or by discretionary decision of the organization; (3) access through meetings, including public hearings or advisory meetings or closed meetings; and (4) access through informal means, such as whistleblowers or leaks when confidential documents are provided to individuals, government agencies, other groups, or the press, generally in order to focus attention on mismanagement, corruption, or other purposes.

Other mechanisms for access to information also exist. For example, the funders of an organization (or the founding partners of a PPP) can require the reporting of certain information to the funders and the founders and of other information to the public as a condition of receiving financial support. Members of the board of directors may have exceptional access to internal information through regular meetings; these members can include the core partners, noncore partners, and others, depending on how broadly board representation is decided by the partnership. Finally, peer-reviewed publications and evaluations can result in public access to information, including full and original data sets for analysis.

It is worth noting several reasons why we care about transparency for PPPs. First, transparency contributes to learning. Transparency allows others the opportunity to avoid making the same mistakes and advances knowledge about how to improve the role of PPPs in global health. Through access to information about inputs, processes, outputs, and outcomes, others can learn about what works, how efficient different approaches are, the comparative strengths and weaknesses of different strategies and structures, and many other aspects of partnership performance. Access to information is a necessary but not sufficient condition for learning.

Second, transparency contributes to democracy. Because PPPs are intended to fulfill public interests, one can argue that the public has a right to know (in a democratic society) about what these organizations are doing and how they are operating. Laws on the right to know, however, usually apply to government agencies and public records. When PPPs take on public-sector functions, the contracts can include confidentiality clauses that limit access to information within the partnership organiza-

tion.22 These restrictions can limit public information and public deliberation about the specific PPP and its activities.

Third, access to information can contribute to accountability, as discussed below in more detail. But transparency (and access to information) does not necessarily result in action to hold a partnership accountable. An organization can provide partial or altered information to shape perceptions of what it is doing, or it can provide an overwhelming amount of information in ways that obstruct accountability. In addition, action does not always follow access to information.

Fourth, transparency can shape organizational performance. If a partnership is required to report on certain metrics (such as number of patients treated), then the PPP could tend to seek to produce to that metric. There may be financial incentives and reputational benefits to report (and to act) in ways that show positive trends in information disclosed.

Finally, transparency can contribute to public perceptions of a partnership. Decisions about transparency shape the positive and negative information and images that exist in the public sphere about a partnership. PPPs may decide not to disclose information that could be viewed as harmful or negative, as part of their public relations strategies, or they may use positive information to boost the partnership’s public image and reputation. In addition, PPPs may use their transparency policies to highlight the organization’s adherence to ethical standards for partnerships.

In conclusion, PPPs shape the transparency they provide by deciding how to use different access-to-information mechanisms to channel certain kinds and quality of information to different audiences. Partnerships tend to have large latitude in deciding what information is provided to whom, the quality of that information, and how it is provided, depending on the nation where the partnership is registered and the legal requirements for such organizations in that country (which sets the minimal rules for transparency). The legal requirements will also vary, however, depending on whether the PPP is registered as a formal organization, the kind of organization, and the national laws related to that organizational form.f It should also be noted, however, that transparency for a PPP has costs (in terms of preparing and releasing information to different actors and audience) and also can have risks (since releasing information can result in consequences that may negatively affect the partnership). The complexity of transparency in practice (as described above) also complicates the challenges of measuring the degree of transparency for a particular organization. It may therefore be more appropriate to think about transparency with regard to a particular actor, rather than trying to create an aggregate measure across diverse audiences.

ACCOUNTABILITY

Accountability, as with transparency, is a contested concept with multiple definitions. I find the definition provided by Edward Rubin to be useful, as it captures many common elements of the concept23:

[t]he ability of one actor to demand an explanation or justification of another actor for its actions and to punish the second actor on the basis of its performance or of its explanation.

These two elements are often called “answerability” and “sanctions.” Accountability (in democratic societies) is typically considered for elected officials (both legislators and the chief executive), and that form of accountability is exercised (in the traditional view) through elections. Many problems exist with the notion of elections as a mechanism for assuring accountability;23 and these problems are well known. As Rubin wrote in 2005, elections as accountability depends on the idea that

an elected official must answer to his constituents for his actions. A realistic, contemporary consideration of elections suggests that this relationship to accountability, although not entirely absent, is a relatively minor aspect of the electoral process.

(One need only glance at the current state of public affairs in Washington, DC, to understand the limitations of elections as accountability mechanisms.)

Rubin also argues that accountability can only be exercised in a hierarchical relationship between superior and subordinate (which I do not agree with, especially for partnerships), and according to concrete standards (which I do agree with).23 Rubin concludes by saying that his goal is not to solve the problem of administrative accountability but “simply to indicate that holding someone accountable is a complex, technical task.”23 This process of “holding accountable” is further complicated in PPPs by the challenges of trying to hold a partner accountable—a problem that may not have been anticipated when the partnership began. In addition, holding someone or a partner accountable is more than a technical task, since it involves questions of values (e.g., which targets are selected for assessing performance) and power (e.g., how actors are pressured to comply). In short, accountability involves ethics and politics as well as technical challenges. For example, accountability may be exercised through specific sanctions for nonperformance related to an agreed-upon metric, but it may also occur through public criticism and conflict that damage a PPP’s reputation and thereby negatively affect the partnership’s ability to operate.

What does this mean for PPPs in global health? Let’s consider

accountability for PPPs, first according to relationships and then according to metrics.

As with transparency, accountability needs to be addressed through bilateral relationships: Who is holding the PPP accountable? PPPs have a variety of stakeholders who could seek to hold the organization and its officers accountable. Perhaps most directly involved are the founding or core partners, which typically provide funding to initiate the PPP and have agreements and contractual obligations to uphold. These core partners are often represented on the partnership’s board of directors or its executive committee, where key strategic decisions are made and supervised. Other nonfounding partners (who may or may not be on the board) also have strong interest in asserting accountability for a PPP, including the intended beneficiaries, related civil society organizations, and relevant governmental or international agencies. National regulatory bodies in the countries where the PPP operates also have a relationship with the PPP that can be expressed through accountability. National legislative and executive authorities may have an accountability relationship with a PPP, depending on the field of action for the PPP and the national political context. Whether a PPP is registered as an independent entity (and the kind of organization) in a particular political jurisdiction will have important implications (including legal obligations) for who holds the partnership accountable (and for what and how), as noted above for transparency.

Ambiguous roles and responsibilities in a partnership complicate the process of holding a PPP accountable. Kamya et al. contrast the partnership model of relationships with the contractual model. They state that24

[u]nlike contractual relationships where roles and responsibilities are demarcated and enforceable and where goals are often set by one party and communicated vertically to another, partnerships are defined by flexible and dynamic allocation of roles and responsibilities and mutual decision making and goal setting.

In their paper, Kamya et al. evaluate the Gavi partnership for human papillomavirus (HPV) applications in Uganda and find that the lack of clear guidelines about roles, responsibilities, and terms of references probably reduced efficiency in operations. They conclude, “[t]he existence of many capable partners does not ensure clear expectations and management of activities and processes.”24 In short, in this case, it was not clear who was accountable to whom, and this ambiguity created confusion.

The next question is: Accountable for what? Here it is useful to refer back to the four categories of information discussed above for transparency: inputs (resources that go into a program or organization), processes (activities undertaken by the program or organization, including how

decisions and plans are made), outputs (what is produced by the activities), and outcomes (the ultimate performance goals or benefits produced by the program or organization). These categories relate to the concepts typically used in logic models for evaluation.25 As part of assuring accountability, a partnership could have specific metrics or procedures specified as performance targets for these four categories. Different stakeholders could have different interests and capacities for different kinds of targets, and they may seek to hold the partnership accountable for different kinds of performance metrics. Outsiders, for example, may be keenly concerned with processes used in partnerships, since it can allow them to participate and have voice in decision making, and thereby influence decisions and performance on results. Insiders may focus on staff performance metrics for deciding on both sanctions and incentives, and thereby influence partnership production of both outputs and outcomes. Insiders, for example, could use “management by objectives” and “key performance indicators” to hold executives or groups or projects responsible for specific targets, with sanctions and rewards depending on performance.

Holding a partnership accountable for final outcomes (such as changes in health status, client satisfaction, or financial risk protection)21 often involves complex questions of assessing causation. To what extent can partnership actions be causally associated with a specific outcome, and how can you know?26 A rigorous study to evaluate how a partnership’s actions affect outcomes often entails high costs and can still have high uncertainty, due to multiple factors that affect outcomes (beyond the specific intervention) and that are not under the partnership’s control. An evaluation of 120 pharmaceutical industry-led access-to-medicine initiatives (all listed on the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers & Associations [IFPMA] Health Partnerships Directory) found, despite frequent claims of positive impacts, only 47 evaluation studies, and all except three were of low or very low quality.26 Uncertainty in causal attribution requires careful study design and interpretation of analytical results. Whether to hold a partnership accountable for specific outcomes, and if so, which ones, therefore, represent complex questions.

The third aspect for accountability is: How? What mechanisms can be used to implement PPP accountability for different stakeholders? Many accountability mechanisms exist that can be (and are) applied to partnerships. Boards of directors (representing different perspectives) review performance assessments of partnership executives and decide on both incentives (such as financial bonuses) and sanctions (such as firing and demotions). Core partners may decide to increase their financial commitments to a PPP, reduce their funding, or even exit a partnership, based on changes in key performance indicators. National regulatory authorities may require partnerships to submit annual financial reports to allow the

PPP to continue operations within a country. Civil society organizations may use both procedural and substantive measures to assess PPP performance and then using various strategies (public information campaigns, lobbying politicians, public interest lawsuits) compel the partnership to change its activities or reward the PPP. Open meetings or hearings, attended by key stakeholders, may provide a mechanism for assessing procedural or substantive metrics and for allowing public review and criticism, thereby advancing accountability through impacts on public reputation for the PPP. But such public meetings can also be designed to avoid serious questions and consequences, thereby avoiding accountability. In some cases, a partnership may sign contracts with key stakeholders (core partners or beneficiaries) as a way of setting specific performance metrics and specifying consequences if those metrics are not achieved within certain time periods. The judiciary can also serve as an important force for holding partnerships accountable when other mechanisms are not effective.

In conclusion, holding a PPP and partners accountable seeks to assure that a partnership is achieving its public interest objectives, and if not, helps to identify what can be done to improve that performance.g Analysis of accountability therefore must be connected to practical action.

IMPLICATIONS FOR ANALYSIS AND ACTION

The above discussions of transparency and accountability, while seemingly abstract and theoretical, have practical implications for both analysis and action. To illustrate some of these implications, I have combined the concepts of transparency and accountability into a “governance matrix for PPPs” (see Table A-2). This descriptive tool allows one to analyze the characteristics and levels of transparency and accountability for a particular organization, and it can also be used as a planning tool to design transparency and accountability relationships for a new PPP. Table A-2 applies the governance matrix to a hypothetical partnership, to illustrate how the matrix can be used to describe and assess transparency and accountability for a specific PPP. (Note: this hypothetical example is not intended to be either an ideal or a typical partnership, but rather to illustrate how the matrix might be used.)

One important caveat needs to be noted before we explore this matrix. Our intuition tells us that improved governance should lead to improved performance by helping partnerships learn, by correcting nonproductive practices, and by removing or punishing individuals or partners that do not contribute to social goals and PPP objectives. But few systematic studies have been conducted to assess the connections between either transparency or accountability and the performance of partnerships, mak-

| Relationship: Party B | Contents | Mechanisms | Level (High/Low) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information to? | Information on? | How informed? | ||

| Transparency: Party A (PPP) | General public | Limited number of outputs | Annual report available on PPP webpage | Low |

| Beneficiaries | Information on a few outputs | Written report and public meeting | Low | |

| Board of directors | Detailed reports on key inputs, processes, outputs | Board meetings, financial and operating reports | High | |

| Accountable to? | Accountable for? | How accountable? | ||

| Accountability: Party A (PPP) | General public | Limited number of metrics | PPP webpage, public hearings | Low |

| Beneficiaries | A few metrics on outputs | Ombudsman and complaints, using public pressure and reputation | Low | |

| Core partners | Detailed metrics on inputs, processes, outputs | Annual reviews of key staff, with firing or bonus, and of key partners | High |

NOTES: Contents for Transparency includes inputs, processes, and outputs; Contents for Accountability includes inputs, processes, and outputs; for Mechanisms for Transparency and Accountability, see discussion above.

ing it difficult to draw firm causal conclusions. According to one systematic review, case studies for some partnerships suggest various kinds of positive impacts, “at least in certain settings.”27 We need to know more, however, if recommendations are to be based on expected consequences.

First, for transparency, the analyst selects a relationship between the PPP and some party B (such as the general public, beneficiaries, or board of directors). The contents of transparency are then described according to the kind and quality of information made available in the transparency relationships (key outputs, a few outputs, or detailed information

on inputs, processes, and outputs), and the mechanisms for making this information available are then entered (annual reports on a website, simple written reports physically distributed, or distribution of detailed operational and financial reports at a closed board meeting). These descriptions then allow a judgment about the level of transparency provided for each relationship (high or low).

The analyst then conducts a similar assessment for accountability. The analyst selects a relationship between the PPP and some party B (such as the general public, beneficiaries, or core partners). The contents of accountability are then described according to (1) the kind of standards used in the accountability relationships (few or many procedural or substantive standards) and (2) the mechanisms for assuring that the performance standards are met by the organization (accountability through public information on a webpage, accountability through reports provided to beneficiaries, or accountability through performance reviews of key PPP staff, followed by sanctions or rewards depending on performance). These descriptions then allow a judgment about the level of accountability provided for each relationship (high or low).

This governance matrix leaves many questions unanswered. The metrics by which each dimension is measured need to be defined. There are operational questions about how to collect the information for the matrix, on both transparency and accountability, and judgment questions about how to assess levels as high or low. Some of these questions can be addressed through repeated practice and use of the tool by actual partnerships. Also, the levels of transparency and accountability may change over time as the partnership evolves. This reflects the need to monitor the implementation process and to assess gaps between expected performance in transparency and accountability and actual performance. Finally, the matrix may be applicable to other kinds of PPPs (those outside of global health) and to other organizations (beyond partnerships, such as public agencies, academic institutions, and private entities).

This approach to transparency and accountability can also be used for normative evaluation (that is, setting specific performance targets), but that raises process implications. What is the desirable level of transparency and accountability for a PPP, and for which audiences, within a particular country? Who should set those levels, and how? In short, who sets the normative rules for PPPs? We could, for example, consider a set of “minimal” standards of governance of PPPs, or even provide a scale of standards from bronze- to silver- to gold-level governance (as one reviewer suggested). This question returns us to broader normative issues about the governance of PPPs, to assure that these organizations are meeting the social goals and public interests that they are intended to pursue.

Four broad options emerge to address these normative questions: by nation, by industry, by international organization, or by nongovernmental organizations.

One possible approach is to assign this responsibility to each nation. National regulatory agencies and national law could address (as currently happens for charitable organizations, for example) the governance requirements of PPPs, specifying the levels and mechanisms of transparency and accountability required. These laws could include tax reporting requirements and activity reporting requirements, to assure that a partnership continues its status as a charitable organization. This approach, however, could introduce legalistic restrictions to partnerships, and thereby diminish their flexibility and innovative capacity to address problems not easily handled by governments (one of the proposed key advantages of PPPs).

A second approach would be for each industry to develop its own standards (through an approach of self-regulation) for transparency and accountability of PPPs. IFPMA, for example, has a website with a directory of more than 250 “health partnerships.”28 IFPMA could set industry metrics and expectations for these partnerships, and ask each organization to complete its own governance matrix. The metrics then might be different for different industries, for instance, for pharmaceutical companies, food companies, petroleum companies, and others. This approach raises problems of the limited effectiveness of self-regulation.

A third approach would be for an international or multilateral agency to propose good practice standards for governance of PPPs. This would cut across different types of PPPs and could be integrated into the Sustainable Development Goals. It could include the development of a symbol of “good partnership practices,” provided by an independent organization, such as the symbol for environmentally caught seafood29 or the Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval30 or an ISO 9000.31 These globally accepted standards of good partnership practice could then provide the basis for audits, which would assure that the mechanisms of transparency and accountability function as intended.

A fourth approach would be for PPPs to develop their own code of good partnership practices. This code could include specific metrics and processes for both transparency and accountability and could define specific audiences as important relationships for partnerships. An association of PPPs could then define membership based on compliance with the code and on audits to demonstrate acceptable performance by a specific organization.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, this proposal for a simplified model offers a number of suggestions about how to think about the governance of PPPs, with a focus on transparency and accountability. I present the proposal in the spirit of seeking to move the discussion forward, clarify some of the key concepts, and indicate ways to apply the ideas in practice. I hope that the proposal will help improve thinking and action about the governance of PPPs in global health.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This paper is based on the keynote address prepared for the Forum on Public–Private Partnerships for Global Health and Safety: Exploring Partnership Governance in Global Health—A Workshop, October 26, 2017, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Washington, DC.

The paper benefited from several discussions with Peter Rockers and Veronika Wirtz, and from comments on earlier drafts by Michael Goroff, Anya L. Guyer, Cate O’Kane, and Rachel Taylor, from participants at a seminar at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and from comments received from participants at the National Academies workshop.

NOTES

a. The “five characteristics of high-performing PPPs,” according to the report, are (1) adopt overall strategy and role, (2) leverage the power of the private sector, (3) nurture partnerships with government, (4) invest in knowledge, and (5) plan for sustainability. For further information on what these characteristics mean and how they were derived from the analysis of a single case study, see ref. 10.

b. This article on global health partnerships identifies seven “unhealthy habits,” although the authors do not explain the methods they used to reach these conclusions. They state: “We argue that GHPs [Global Health Partnerships] skew national priorities of recipient countries by imposing those of donor partners; deprive specific stakeholders a voice in decision-making; demonstrate inadequate use of critical governance procedures; fail to compare the costs and benefits of public versus private approaches; fail to be sufficiently resourced to implement activities and pay for alliance costs; waste resources through inadequate use of country systems and poor harmonisation; and do not adequately manage human resources for partnering approaches.” See ref. 11 for additional details.

c. While I did not conduct a systematic analysis of the titles retrieved, the literature scan was very helpful in identifying some key publications related to PPP governance, and I have used them in writing this paper and included them as references.

d. I decided not to include “participation” as a separate dimension of PPP governance because it seemed to me to be a key component of both transparency and accountability (through the relational nature of both concepts), because it seemed to be a mechanism to achieve transparency and accountability more than a separate dimen-

sion of governance, and because a three-dimensional matrix is too hard to visualize, keep in mind, and use in practice.

e. Private health care organizations (such as hospitals) that engage in mergers and acquisitions, on the other hand, can be required by state law in the United States to submit detailed financial reports to state agencies (for example, on price and quality) in order to evaluate likely impacts on consumers. They can also be required to provide annual financial statements (on revenues, profit/losses, and debt) on a regular basis. In some cases, however, private hospital chains have refused to provide these detailed reports and as a result have been subjected to fines for noncompliance and threats of noncertification. See: Priyanka Dayal McCluskey, “Steward Health Care Fails to Submit Financial Data as it Expands,” Boston Globe, 2 September 2017, p. 8.

f. The decision of whether to register a partnership as an independent entity (or locate within an existing entity) has important implications for both governance and operations. For example, if a PPP seeks to receive tax-deductible donations in kind or in cash in the United States, it frequently registers as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that is exempt from federal taxes under the U.S. tax code (one of 29 types of tax exempt organizations under 501(c)). This 501(c)(3) status as a private charity or public foundation also results in certain reporting requirements and limitations on political activities, with fines for noncompliance, and thereby shapes both transparency and accountability.

g. It is worth noting that some PPPs (for instance, for service delivery within national health systems) have been criticized for conflicts of interest and not serving public health goals or public welfare. See: Sujatha Rao, “A Strange Hybrid,” The Indian Express, 11 August 2017, http://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/niti-aayog-a-strange-hybrid-public-hospitals-government-4791233.

REFERENCES

1. Taylor, Rachel. “Invitation to Speak at National Academies Workshop on Global Health PPP Governance,” Email to author, 12 July 2017.

2. Reich, Michael R., ed., Assessment of TDR’s Contributions to Product Development for Tropical Diseases: Three Cases. Geneva: UNDP/World Bank/WHO Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases, 1997.

3. Reich, Michael R., ed., An Assessment of U.S. Pharmaceutical Donations: Players, Processes, and Products. Boston: Harvard School of Public Health, 1999.

4. Frost, Laura, Michael R. Reich, and Tomoko Fujisaki. “A Partnership for Ivermectin: Social Worlds and Boundary Objects,” in Michael R. Reich, ed., Public-Private Partnerships for Public Health. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002, pp. 87-113.

5. Ramiah, Ilavenil, and Michael R. Reich. “Public-Private Partnerships and Antiretroviral Drugs for HIV/AIDS: Lessons from Botswana.” Health Affairs 24(2): 545-551, 2005.

6. Reich, Michael R., ed., Public-Private Partnerships for Public Health. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002.

7. Institute on Governance. “Defining Governance.” http://iog.ca/defining-governance (accessed June 4, 2018).

8. Reich, Michael R. “Public-Private Partnerships for Public Health,” in: Michael R. Reich, ed., Public-Private Partnerships for Public Health, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002, pp. 1-18.

9. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. “Partnership Governance in Global Health, Annotated Bibliography of Selected Resources.” Prepared as an initial reference document for the Workshop on Exploring Partnership Governance in Global Health Planning Committee. Washington, DC: NASEM, 2017.

10. FSG. Adapting Through Crisis: Lessons from ACHAP’s Contributions to the Fight Against HIV/AIDS in Botswana. Boston, MA: FSG, 2014.

11. Buse, Ken, and Andrew M. Harmer. “Seven Habits of Highly Effective Global Public-Private Health Partnerships: Practice and Potential.” Social Science & Medicine 64: 259-271, 2007.

12. Buckup, Sebastian. “Global Public-Private Partnerships Against Neglected Diseases: Building Governance Structures for Effective Outcomes.” Health Economics, Policy and Law 3(Pt 1): 31-50, 2008.

13. Bezanson, Keith A., and Paul Isenman. Governance of New Global Partnerships: Challenges, Weaknesses, Lessons. CGD Policy Paper 014. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development, 2012.

14. Bears, Daniel. Literature Scan—Commissioned Paper for Exploring Partnership Governance in Global Health. Washington, DC: NAS Research Center, 11 August 2017.

15. Pyone, Thidar, Helen Smith, and Nynke van den Broek. “Frameworks to Assess Health Systems Governance: A Systematic Review.” Health Policy and Planning 32: 710-722, 2017.

16. Fox, Jonathan. “The Uncertain Relationship Between Transparency and Accountability.” Development in Practice 17(4-5): 663-671, 2007.

17. Scott, C. Figuring Out Accountability: Selected Uses of Official Statistics by Civil Society to Improve Public Sector Performance. Q Squared Working Paper No. 37. Toronto: Centre for International Studies of the University of Toronto; 2007. Accessed 19 August 2017 at: https://www.trentu.ca/ids/sites/trentu.ca.ids/files/documents/Q2_WP37_Scott.pdf.

18. Vian, Taryn, Jillian C. Kohler, Gilles Forte, and Deidre Dimancesco. “Promoting Transparency, Accountability, and Access Through a Multi-Stakeholder Initiative: Lessons from the Medicines Transparency Alliance.” Journal of Pharmaceutical Policy and Practice 10(18): 1-11, 2017.

19. CHESTRAD International. Institutionalize, Resource and Measure: Meaningful Civil Society Engagement in Global and National Health Policy, Financing, Measurement and Accountability. United Kingdom: CHESTRAD International, June 2015.

20. Reynaers, Anne-Marie, and Stephan Grimmelikhuijsen. “Transparency in Public-Private Partnerships: Not So Bad After All?” Public Administration 93(3): 609-626, 2015.

21. Roberts, Marc J., William C. Hsiao, Peter Berman, and Michael R. Reich. Getting Health Reform Right: A Guide to Improve Performance and Equity. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

22. Sands, Valerie. “The Right to Know and Obligation to Provide: Public Private Partnerships, Public Knowledge, Public Accountability, Public Disenfranchisement and Prison Cases.” UNSW Law Journal 29(3): 334-341, 2006.

23. Rubin, Edward. “The Myth of Accountability and the Anti-Administrative Impulse.” Michigan Law Review 103: 2073, 2005.

24. Kamya, Carol, Jessica Shearer, Gilbert Asiimwe, Emily Carnahan, Nicole Salisbury, Peter Waiswa, Jennifer Brinkerhoff, and Dai Hozumi. “Evaluating Global Health Partnerships: A Case Study of a Gavi HPV Vaccine Application Process in Uganda.” International Journal of Health Policy and Management 6(6): 327-338, 2017.

25. McLaughlin, John A., and Gretchen B. Jordan. “Logic Models: A Tool for Telling Your Program’s Performance Story.” Evaluation and Program Planning 22: 65-72, 1999.

26. Rockers, Peter C., Veronika J. Wirtz, Chukwuemeka A. Umeh, Preethi M. Swamy, and Richard O. Laing. “Industry-Led Access-to-Medicines Initiatives in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Strategies and Evidence.” Health Affairs 36(4): 706-713, 2017.

27. Gaventa, John, and Rosemary McGee. “The Impact of Transparency and Accountability Initiatives. Synthesis Report.” Development Policy Review 31(S1): S3-S28, 2013.

28. IFPMA. “Health Partnership Directory.” Web page. http://partnerships.ifpma.org/partnerships/by-letter/all (accessed April 16, 2018).

29. Marine Stewardship Council. “The Blue MSC Label: Sustainable, Traceable, Wild Seafood.” https://www.msc.org/about-us/blue-msc-ecolabel-traceable-sustainable-seafood.

30. Good Housekeeping. “About the Good Housekeeping Seal.” http://www.goodhousekeeping.com/product-reviews/seal (accessed April 16, 2018).

31. International Organization for Standardization. “ISO 9000 – Quality Management.” https://www.iso.org/iso-9001-quality-management.html (acceseed April 16, 2018).