2

Perspectives on the Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases in an Urban and Interconnected World

During the opening session, two speakers set the stage by exploring current challenges and opportunities for the prevention and control of infectious diseases in an increasingly urban and interconnected world. Christopher Dye, director of strategy, policy, and information at the Office of the Director-General of the World Health Organization (WHO), provided a global perspective on those challenges and opportunities, focusing on how global initiatives like Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development,1 commonly known as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), can contribute to countering microbial threats in the urban environment. A local perspective that highlighted the role of slums in global disease transmission was offered by Alex Ezeh, former executive director of the African Population and Health Research Center in Kenya.

POTENTIAL CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES AT THE GLOBAL LEVEL

The SDGs came into force as a nonbinding international agreement in 2016, consisting of 17 global goals that span 169 specific targets to be

___________________

1 The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development is available at www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/development-agenda (accessed January 11, 2018).

achieved by 2030,2 with the overarching aim of promoting sustainable development by harmonizing the interconnected elements of economic growth, social inclusion, and environmental protection. Christopher Dye, director of strategy, policy, and information at the Office of the Director-General of WHO, explored how the SDGs could contribute to mitigating microbial threats in urban environments, noting the diversity of opinions about the potential impact of the agenda. He suggested that the agenda could indeed serve as a “guiding light” for development, with the proviso that it be treated as an agenda for research—that is, a set of testable ideas—and not as a blueprint for development.

Dye maintained that the SDGs reflect a shift in thinking about health in the context of development. He explained that the antecedent to the SDGs, the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs),3 were focused on time-limited, vertical programs targeting principal causes of illness and death in low-income countries, with particular focus on communicable diseases and on the major causes of death among women and children. The proposition for development underpinning the SDGs is different, according to Dye, because its focus is on building horizontal, sustainable, and effective health systems to accelerate health gains through treatment and prevention. This includes health systems concerned with public health and the traditional provision of medical and clinical services, he continued, as well as systems that bring health together with agriculture, education, transportation, energy, industry, and other sectors. Dye commended this broader systemic view, but he cautioned that it will require a host of new ideas to succeed in advancing health.

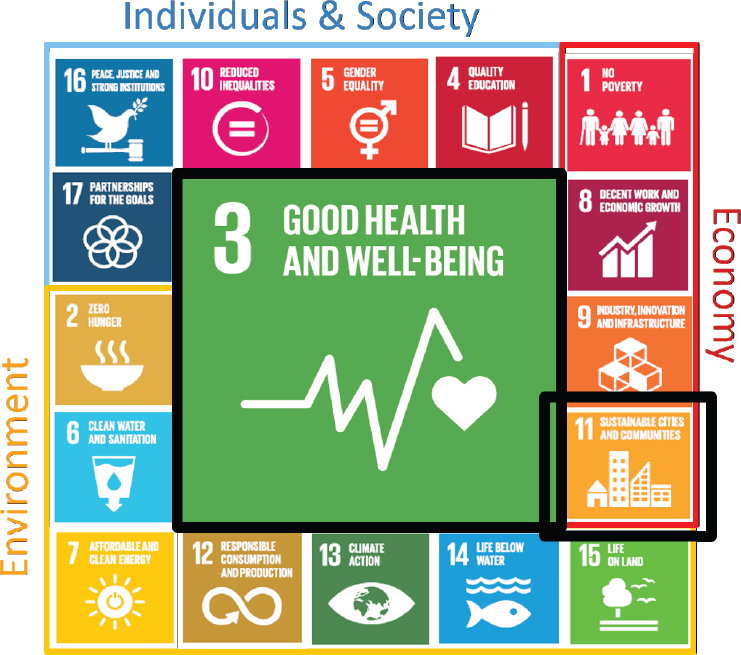

SDG 3 (“good health and well-being”) both depends on and contributes to many of the other SDGs, explained Dye. He described how the relationship between health and the urban environment surpasses the binary relationship between SDG 3 and SDG 11 (“sustainable cities and communities”), because the landscape of urban health is also contingent upon goals related to poverty, education, equity, food, energy, industry, and other sectors (see Figure 2-1). This is reflected in another shift in perspective, he said, from a focus on activities organized around the burden of disease and major causes of death worldwide to activities focused on health, but not organized around specific infectious diseases. For example, new activities aimed at setting priorities for improving the urban environment are orga-

___________________

2 The 17 SDGs include no poverty; zero hunger; good health and well-being; quality education; gender equality; clean water and sanitation; affordable and clean energy; decent work and economic growth; industry, innovation, and infrastructure; reduced inequalities; sustainable cities and communities; responsible consumption and production; climate action; life below water; life on land; peace, justice, and strong institutions; and partnerships for the goals.

3 Established in 2000, the MDGs were a set of eight international development goals with targets to be achieved by 2015.

SOURCES: Dye presentation, December 12, 2017; adapted from WHO, 2017b. Reprinted from Health in the SDG era, Copyright (2017).

nized around the processes that underlie developing urban systems, he said, rather than focusing only on specific diseases as causes of illness and death.

Specifically, Dye reported that the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) reviewed 5,000 initiatives from 140 countries to identify best practices for developing the urban environment, and set forth priorities, including slum upgrading; water, sanitation, and hygiene services; housing; urban governance; urban planning; and urban economy.

Dye characterized the persistent decline in mortality among children under 5 years of age as a spectacular success of the previous half century. He explained that, although rates declined across high-, middle-, and low-income countries throughout this period, there was an accelerated decline in low-income countries, where the mortality rate began to converge with rates for middle- and high-income countries between 1990 and 2015. Dye

noted that this period of convergence was largely coincident with the MDG era, but suggested that much of the success achieved during that era was driven by factors that were not explicitly taken into account at the time. He cited an analysis that found that only around half of the overall reduction in child mortality was attributable to health services and direct medical interventions, such as vaccines, oral rehydration, or antibiotic treatment (Kuruvilla et al., 2014). The remaining proportion was attributed to efforts addressing deeper causes and risks, including reducing population fertility; increasing female political and socioeconomic participation and primary education; improving environmental factors; economic development; and decreasing income equality. According to Dye, the reduction in child mortality is inexplicable without these primary prevention factors, which can be roughly aligned with various SDGs. Dye maintained that forging links between health and the other SDGs would promote the development of health systems that are oriented not only toward treatment but also toward cost-effective prevention.

Bolstering Systems That Promote Health

Dye explored some of the characteristics of systems that serve to promote health and well-being, which he discussed in two categories. With regard to the first category, he explained that sustainable systems for health require active work on health across all sectors of government, and such systems should provide universal health coverage to the population. With respect to the second category, he outlined five properties of effective systems fostered by the SDGs: affordable, equitable, measurable, testable, and sustainable. Dye framed his discussion of bolstering systems to promote health using these two categories.

Sustainable Systems for Health

Dye reported that the profile of health in the development sphere is on the rise, which is a legacy of the MDG era being propelled in the SDG era. Discussions taking place at the highest levels of international organizations are being mirrored at the level of many national governments, he said, and health matters are increasingly considered matters for the whole of government and not just the ministry of health. Developments in intersectoral work on health are also under way, said Dye. He reflected that 30 years ago he had to stop his work on the biology of leishmaniasis transmission in the Amazon,4 because lack of interest in the disease frustrated his efforts to

___________________

4 Leishmaniasis is a parasitic disease transmitted by bites of phlebotomine sand flies that can cause sores on the skin or affect internal organs.

translate his biology research findings into real public health actions. However, he said, this changed substantially when leishmaniasis was classified as a neglected tropical disease, raising its profile and driving the development of new control strategies, such as canine vaccines to prevent transmission of visceral leishmaniasis to humans.

Years ago, he remarked, urbanization was not even considered a factor, despite observations that there was no leishmaniasis in settlements on the edge of towns, where people lived in different types of housing than areas affected by the disease. Today, it is well established that good housing engenders multiple health benefits and is part of the solution for leishmaniasis and other issues, said Dye, because poor-quality housing and neglected peridomestic environments are risks for vector-borne and other illnesses. He attributed this development in part to the broadening of perspective the SDGs are bringing to the fore, which is driving innovation in housing design to strengthen vector control. However, he warned that, despite the well-known broader and sustainable benefits of quality housing for a population, efforts to improve housing are often neglected in favor of other interventions. According to Dye, this is because poor housing is generally seen as a relatively weak risk factor for vector-borne and other illnesses, so it is often sidelined for efforts focusing exclusively on disease-specific interventions (for example, bed nets for malaria control).

Dye suggested channeling research and funding toward better quantitative systems analyses of the interactions among different SDGs and of different potential interventions. He cited a study that analyzed the relationship between SDG 3 and SDG 11, which found a key interaction between housing and respiratory disease (Griggs et al., 2017). This type of work may serve as a starting point for addressing diseases in the urban environment, he noted, but advised that deeper, more detailed work will be needed to identify connections that can be leveraged to devise better disease control programs.

Dye described a study he co-authored on tuberculosis (TB) to illustrate the complexities at play in this type of analysis (Dye et al., 2011). The study began with the observation that undernutrition is a risk factor for TB, yet overnutrition can also be a risk factor for TB via the onset of diabetes mellitus—Dye termed this a “vicious triangle.” Both undernutrition and overnutrition are affected by aging, urbanization, and other potential cofactors, he said, so he and his colleagues analyzed the interacting factors to identify the most important drivers of TB in populations in India and Korea. They concluded that demographic factors were the strongest drivers, rather than diabetes or nutrition per se.

Properties of Effective Systems Fostered by the SDGs

Dye explained that universal health coverage is a component of sustainable systems for health as well as a contributor to the properties of effective systems fostered by the SDGs, including affordability and equity. Universal health coverage is a matter of economics as well as equity, he maintained. He reported that as of December 2017, around 12 percent of the population spend more than 10 percent of their household budget on health services, which risks pushing them into poverty (WHO and World Bank, 2017). Although universal health coverage has been called an “affordable dream” by economist Amartya Sen, Dye warned that affording it will be difficult under a number of circumstances. He explained that, per WHO statistics, public expenditure on health as a fraction of gross domestic product has been rising worldwide as well as in low-income countries, albeit slowly. He added that rates of out-of-pocket expenditure as a percentage of health expenditure—which drives people into poverty—have been falling, but also slowly. The question at hand, said Dye, is whether these slow trends will continue or if mechanisms could be implemented to bend these curves upwards or downwards.

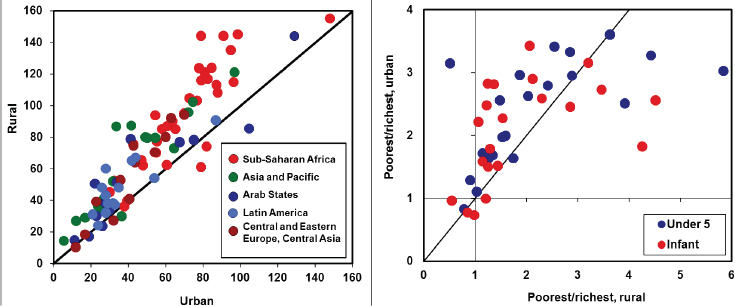

Urbanization is the catalyst for various dilemmas of inequity, said Dye. Many of the poorest people migrate to slums because the circumstances there are often better for them than in rural areas, he explained. For example, he reported that, in many countries, rates of infant mortality are higher in rural environments than in urban environments (see Figure 2-2). He noted that, although rates of child mortality tend to be better for poorer people in urban versus rural areas, the inequalities between the poorest and richest people are even greater in urban areas. “Health is better, but inequality is greater too: that is an urban dilemma we need to resolve,” said Dye.

Despite media attention to mounting income inequality worldwide, he remarked, WHO statistics suggest that health equality is steadily improving and that the health gap is slowly narrowing between poor and rich people in low- and middle-income countries. He described a WHO analysis on the composite coverage index for a set of health services that used Demographic and Health Survey data from 42 low- and middle-income countries over roughly 10 years (Dye, 2008).5 It revealed greater relative improvements in the composite coverage index for the poorest quintile versus the richest quintile. He indicated that while inequity in health seems to be declining based on this analysis and others, the real problem is that it is declining too slowly.

___________________

5 The health services include family planning; antenatal care; skilled birth attendance; diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus (three doses) immunization; and care seeking for children with pneumonia.

Left: Infant mortality under 1 year of age per 1,000 live births tends to be higher in rural than in urban areas.

Right: The ratio of child mortalities (infant and under 5 years of age) in the poorest 20 percent of families to the richest 20 percent tends to be higher in urban than in rural areas.

SOURCES: Dye presentation, December 12, 2017; Dye, 2008. Modified from Dye, C. 2008. Health and urban living. Science 319(5864):766-769 with permission.

Although it can be useful to summarize national averages on statistics, said Dye, it is also important to analyze the data in a more detailed, disaggregated way to understand more about who is being left behind—that is, the poorest people in the lowest quintile. Achieving universal health coverage will require more sophisticated measurements and analyses of statistics to understand where the disadvantages lie, he said, and to understand the determinants of socioeconomic circumstances.

To describe the challenge of improving equity, Dye used the case of the 2017 Grenfell Tower fire disaster in central London, England, in which 80 people were killed in a residential tower fire. The tower is in a borough of London where some of the poorest and richest people in the country live alongside each other, he said, and the issue of equity has been the crux of debate and backlash surrounding the circumstances that led to the disaster. Dye explained that this London borough has had essentially the same patterns of rich and poor areas since 1900, highlighting the difficulty in making headway against deeply entrenched social inequities.

Dye concluded by commenting briefly on sustainability and financing of the 2030 agenda. National health accounts are used as the principal measure of how much is spent on health, he noted, but spending is only counted if health is its primary purpose. He cautioned that this is at odds with the SDG agenda’s central ethos of integrating various sectors that have atten-

dant health benefits—such as agriculture, education, and transportation—because spending in those sectors is not counted in financing statistics. Dye used funding statistics from the Ebola virus disease (EVD) epidemic of 2014 to discuss sustainability in the context of how funds are invested. Around $9 billion was pledged and $6 billion disbursed overall, he reported, with more than $4.5 billion of those disbursed funds spent on the rapid response to contain the immediate threat. However, he noted that the amount of disbursed funds spent on response dwarfs the amount invested in improving sustainability through recovery efforts (around $1 billion) and through research and development (around $200 million). Dye emphasized that greater investment in sustainability through systems strengthening, research, and development will be critical for preventing and mitigating the threat of future epidemics and pandemics. He said that, in his experience, the value of investing in research is often questioned by those outside the research community; he urged the research community to continue to impress the value of ongoing and increased investment in research on other sectors. Dye reiterated that the SDGs could serve as a transformative guiding light for development work geared toward sustainability, but only if the goals are treated as testable hypotheses and supported by a closely linked research agenda that can measure the benefits of the SDG approach.

POTENTIAL CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES AT THE LOCAL LEVEL

Alex Ezeh, former executive director of the African Population and Health Research Center in Kenya, opened by remarking that the dynamics of slums are markedly different from those of urban processes as a whole. The growing recognition that slums have unique characteristics that need to be better understood, he continued, is also garnering attention to the role of slums in pathogen transmission and epidemics worldwide. He predicted that as the world becomes increasingly urbanized, effective control of infectious diseases on the global front will hinge upon a better understanding of disease dynamics in urban settings. By 2050, he added, the global population is projected to increase by 2.2 billion people, most of whom will be living in urban areas in low- and middle-income countries.

The challenges faced by people living in slums are tantamount to the challenges of the shared physical and social environments in which they live, remarked Ezeh. The importance of space to people living in slums was underscored by a recent series in The Lancet on slum health (Ezeh et al., 2017; Lilford et al., 2017). For people living in slums, he explained, it is not just an individual’s household poverty status that matters but also the

context within which the individual is living—the neighborhood effects. He added that poverty in and of itself is not a good measure of health in urban areas; given the complex dynamics of urban environments, the drivers of health for people living in slums have less to do with individual wealth compared to the environment in which they live.

Measuring Slums: Statistics Versus Geography

Ezeh pointed out an inconsistency between how slums are measured statistically and what slums actually are. When people think of slums, he said, they typically picture a specific space or geographic location. However, he noted that current estimates and statistics about slums in low- and middle-income countries are derived from UN-Habitat data, which do not characterize slums as specific places. He explained that the following criteria are used to identify people living in slums instead: groups of people or households that lack access to safe water, sanitation, and other infrastructure; people who have insecure tenure within the urban space; and people living in high-density settings (defined as three or more people in the same sleeping room) (UN-Habitat, 2006). Ezeh observed that because estimates based on these data do not refer to the specific geographic locations commonly considered to be slums in low- and middle-income countries, the practical value of these estimates is not entirely clear.

Rising slum populations driven by urbanization in low- and middle-income countries are a major challenge for development going forward, according to Ezeh. Although there has been a significant drop in the proportion of people who live in slums globally since 1990, he said, the absolute number has grown by about 200 million people to roughly 1 billion living in slums today (UN-Habitat, 2016a). In sub-Saharan Africa, the proportion has declined from 70 percent to 56 percent, he added, but the number of people living in slums has more than doubled from about 93 million to about 200 million (UN-Habitat, 2016a). Progress is being made toward helping countries develop better practices for identifying people who live in slums and begin creating strategies for how to help address the specific issues and challenges faced by those populations, said Ezeh. For example, a 2017 meeting in Bellagio, Italy, on slum identification convened representatives from international agencies and the national governments of low- and middle-income countries to strategize about how to deal with slums as a specific development challenge (UN-Habitat, 2017). One objective of the meeting, he noted, was to work toward recognizing slums as geographic entities—with people living in them—in order to capture more accurate information in national data systems and global report estimates.

Understanding the Importance of Slum Health

Ezeh emphasized that better understanding slum health is important, because rural areas and urban areas have fundamentally different health risks, solutions, and opportunities to intervene within their respective settings. He added that there are also distinct dynamics at play in slums versus nonslum areas within urban settings. To highlight the relevance of slum health in global disease transmission and in understanding global health in the 21st century, he outlined five issues:

- Health risks,

- Health determinants,

- Health outcomes,

- Global interconnectedness, and

- Urban inequities.

Ezeh explained that many of the health risks faced by slum residents are driven by their environments, such as overcrowding, poor garbage disposal, poor toilet facilities, lack of affordable clean water, and poor drainage. These are constant features within slums in many low- and middle-income countries, he noted. Furthermore, slum residents are inequitably and systematically excluded from health amenities and services in urban areas that are readily available to nonslum residents, he explained. This is not usually the case in rural areas, he said, where most people have access to the same basic health services regardless of their wealth status.

Slum residents and the urban poor face health risks that are driven by environmental determinants, Ezeh maintained, and these determinants of health may be very different from those in other settings. To illustrate how the challenges and constraints of life in slums can be obfuscated by statistical averages for entire urban areas, he presented data from a longitudinal health and demographic surveillance system carried out in the slums of Nairobi from 2003 to 2016 (Beguy et al., 2015). The leading cause of death in adults 15 years of age and older was TB for both men and women, he reported, but injuries were the second most common cause of death for men (31 percent), which he attributed to the slum setting. For children under 5 years of age, the leading cause of death was acute respiratory infection (38.6 percent of males and 32.5 percent of females), he reported. Ezeh also attributed this to the environment, noting that children under 5 years of age spend much of their time inside homes where indoor air pollution is rampant.

Ezeh explained that not only can health risks and determinants of health differ depending on rural, urban, and slum settings, but health out-

comes can also differ considerably depending on the environmental context. These differences need to be analyzed more precisely in order to intervene effectively, he argued, citing data comparing mortality rates for infants and children under 5 years of age in different settings in Kenya (APHRC, 2002; Government of Kenya, 2004). Children under 5 years of age in slum households have a 30 percent higher mortality rate than children in rural areas, according to a representative survey of slum households in Nairobi. He added that the difference in mortality rates in slums versus nonslum urban areas is much larger than the difference in the mortality rates between urban and rural areas. However, he cautioned that these estimates and indicators of health outcomes in urban areas may be based on data that do not accurately capture slum communities or represent how their health outcomes are distinct from the broader urban setting. He explained that in the city of Nairobi, for example, an estimated 55 percent of the population actually lives in slums, but national survey data indicate that only 20 percent of the people live in slums.

The urbanization of infectious disease epidemics underscores the role of global interconnectedness as a driver of health worldwide, said Ezeh. Similarly, he noted that outbreaks of EVD were confined to small, remote areas in different African countries prior to the 2014 epidemic, but the epidemic precipitated when it reached three capital cities in West Africa. Interconnectedness exacerbates disease transmission risks outside of households, Ezeh said. He reported that contact-tracing data from the 2009 H1N1 influenza epidemic in China revealed that 44 percent of traced close contacts of index cases were passengers on the same flight, 23 percent were at school or work, and 6 percent were service people in public places (Pang et al., 2011).

Low- and middle-income countries have massive urban inequities that also play a role in driving the transmission of infectious disease, said Ezeh. He explained that disease transmission can be accelerated by the lack of physical and social distance between socioeconomic groups in low- and middle-income countries, where there tend to be huge numbers of people who span diverse socioeconomic milieus every day in their work and homes (for example, domestic staff, hospitality workers, gardeners, cleaners, security staff). He described how the 2017 cholera outbreak in Nairobi became an emergency when it stretched beyond the slums and into the five-star hotels and restaurants, transmitted by workers who became infected in the slums where they live. Ezeh contrasted this proximity between socioeconomic groups with a situation in high-income countries, where welfare systems in place may create physical and social distance between socioeconomic groups because the poorest people may be systematically excluded from the workplace.

Ezeh predicted that slums will emerge as the major nexus between the urban and rural, between the formal and informal, and between the local and global. Given that the slums of low- and middle-income countries are the birthplace of many global epidemics, he maintained, slum health cannot continue to be ignored if efforts to control disease and infection on the global front are to succeed.