5

Achieving Sustainable and Health-Promoting Urban Built Environments

Session 2 of the workshop focused on effective interventions and policies aimed at achieving sustainable and health-promoting urban built environments. Prior to the session, Steve Lindsay, professor in biosciences at Durham University, England, outlined global efforts aimed at leveraging the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and promoting healthy lives in urban settings. The session was moderated by Jason Corburn, director of the Institute of Urban and Regional Development and professor of city and regional planning at the University of California, Berkeley. In his presentation, Siddharth Agarwal, director of the Urban Health Resource Centre in India, explored how to build an investment case for slum upgrading and health-promoting urban environments and outlined several methods for infectious disease mitigation that have been implemented in slum environments in India. Daniele Lantagne, associate professor of civil and environmental engineering at Tufts University, discussed examples of context-specific water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) interventions that have been implemented successfully. Eva Harris, professor of infectious diseases and director of the Center for Global Public Health at the University of California, Berkeley, described efforts to engage communities from surveillance to policy. Her presentation focused on the Camino Verde approach to community engagement for vector control, which was the subject of a large, cluster randomized controlled trial across Nicaragua and Mexico.

GLOBAL EFFORTS TO LEVERAGE THE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS TO PROMOTE HEALTH

Steve Lindsay, professor in biosciences at Durham University, England, explored global efforts to leverage the SDGs to improve health, with a focus on health in urban built environments. He opened by describing three major infectious disease threats to urban environments: respiratory viruses, such as pandemic influenza and severe acute respiratory syndrome; Aedes-borne diseases, such as dengue, Zika virus disease, chikungunya, and yellow fever; and locally important diseases, such as plague and malaria in India. According to Lindsay, infectious diseases are a serious and mounting threat to the health of people living in towns and cities around the world, and he suggested that this threat remains underappreciated on an international level. He said that the Aedes aegypti mosquito is an urban vector of chief concern. He noted that dengue fever, for example, is a predominantly urban disease that is increasing worldwide, with an estimated increase in age-standardized dengue cases of nearly 450 percent between 1990 and 2013 (Vos et al., 2015). Lindsay predicted that the number of dengue cases will continue to increase, given the predicted increase in the distribution of Aedes aegypti in large human populations around the world. He warned: “We are so ignorant about the true distribution of this mosquito, this fantastic vector of arboviruses.” Lindsay also expressed serious concern about the ability to control a disease such as yellow fever if it moves into one of the megacities in South America.

Global Initiatives to Mitigate the Risk of Infectious Diseases in Urban Environments

After outlining some of the major infectious disease threats to urban built environments, Lindsay turned to global initiatives aimed at mitigating the risk of such diseases. He said that the SDGs provide an opportunity for improving control of infectious diseases in urban settings because they provide a reason for action. He suggested that, because the SDGs govern and support international documents, they have the potential to contribute to more focused policy documents, to the reorienting of organization of policies going forward, and ultimately to a cultural shift toward multidisciplinary solutions to complex problems.

Lindsay focused on six of the SDGs that he considers potentially helpful in improving the control of infectious diseases:

- SDG 1: No poverty

- SDG 3: Good health and well-being

- SDG 6: Clean water and sanitation

- SDG 11: Sustainable cities and communities

- SDG 13: Climate action

- SDG 17: Partnerships for the goals

He said that the SDGs were influential in helping to develop the new global vector control response from the World Health Organization (WHO). He explained that WHO had a previous global strategy for dealing with vector-borne diseases—a multidisciplinary approach called the Global Strategic Framework for Integrated Vector Management (WHO, 2004)—but the global Zika pandemic, coupled with the SDGs, caused WHO to reexamine global vector control and to produce its Global Vector Control Response 2017–2030, which provides a new strategy to strengthen vector control worldwide through increased capacity, improved surveillance, better coordination, and integrated action across sectors and diseases (WHO, 2017a).

According to Lindsay, another illustration of how the SDGs have helped to develop global health policy is related to SDG 11 (sustainable cities and communities). He said that SDG 11 catalyzed the United Nations Human Settlements Programme’s (UN-Habitat’s) New Urban Agenda, which supports towns and cities in developing strategies to become more resilient to the threats of natural hazards (UN-Habitat, 2016b). Although the new agenda mentions health and vector-borne diseases, he said, much of the current thinking within this field is focused on hazard threats, such as rising sea levels and earthquakes, rather than the threat of infectious diseases. Lindsay highlighted the enormous potential for the health sector to link productively with the group of people who developed the New Urban Agenda. Lindsay also noted that other initiatives flow from the new agenda, including the Global Alliance for Urban Crises1 and The Rockefeller Foundation’s 100 Resilient Cities.2 He suggested that those initiatives could also provide opportunities for people working in health to link with people working on promoting resilience to physical, social, and economic challenges in specific cities. He suggested focusing on engaging the mayors of cities and towns, because they have power, access to financing, and the facilities to take action. He emphasized that infections such as Aedes-borne diseases are environmental illnesses and contended that health should be integrated with work that is already under way to develop these new ideas and initiatives, rather than being a separate strand.

___________________

1 The Global Alliance for Urban Crises is available at www.urbancrises.org (accessed February 10, 2018).

2 The Rockefeller Foundation’s 100 Resilient Cities is available at www.smartresilient.com/100-resilient-cities-rockefeller-foundation (accessed February 10, 2018).

Translating Global Initiatives into Local Action: A Focus on Vector Control

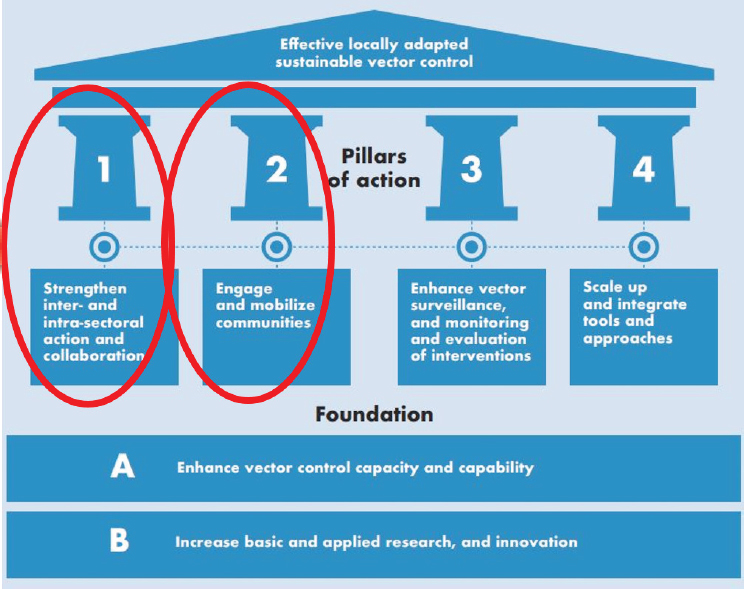

Lindsay discussed some ongoing efforts to translate global initiatives into local action. He explained that WHO’s Global Vector Control Response 2017–2030 can be envisioned as a temple requiring four key pillars to attain locally adapted and sustainable vector control (see Figure 5-1). Two of its four pillars are to strengthen intersectoral and intrasectoral action and collaboration and to engage and mobilize communities. He said that addressing those two pillars is a challenge because the function of intersectoral committees is contingent on commitment at the highest national or

SOURCES: Lindsay presentation, December 13, 2017; adapted from WHO, 2017a. Reprinted from Global Vector Control Response 2017—2030, page ix, Copyright (2017).

local level. He maintained that this is the key for turning policy into action. He said that a national steering committee for improving control of vector-borne diseases, for example, must collaborate with agencies outside of the government ministries of agriculture, finance, environment, and others, as well as collaborate with the private sector, with community groups, and with nongovernmental organizations.

Lindsay said there is a set of tried and tested technologies for control of vector-borne diseases, including insecticide-treated bed nets, fogging, indoor residual spraying, and larval source management. He also noted other underexplored opportunities that are founded on better appreciating the importance of environmental management and city design. For example, he said, the immature stages of Aedes aegypti are carried in water storage containers, used tires, solid waste, and elsewhere. To eliminate aquatic habitats for the vector and reduce the number of adult mosquitos, he explained, strategies that may discourage people from storing water include removing tires, improving waste management, and providing reliable piped water. These types of strategies will not solve the problem, he conceded, but he suggested that they can contribute to the overall control of Aedes-borne diseases in the future, as well as improving people’s living conditions in the present.

Making intersectoral collaboration sustainable is one of the biggest challenges of the century, according to Lindsay, but he suggested that effectively controlling infectious disease in urban environments will need to include collaborating and gleaning lessons learned from organizations outside the health sector. He further suggested that turning policy into action will require “breaking the mold” within the health sector by engaging with communities and with nonhealth sectors. The ethos should be health in all policies, he said, not just the deployment of tools (WHO, 2013). Lindsay cautioned that establishing intersectoral collaboration may be challenging against the current background of weak health systems and the unknown effectiveness of existing interventions, particularly for interventions against Aedes-borne diseases. He also mentioned the lack of research and investment into methods for controlling, intervening, and monitoring and evaluation of these diseases. In cities in tropical and subtropical regions, he suggested that efforts should focus on controlling Aedes-borne diseases. Lindsay commended the Sudan National Intersectoral Committee for Vector Control as an instructive example of a successful and effective interdisciplinary approach to controlling malaria by removing aquatic breeding habitats in Khartoum, Sudan. He concluded by reiterating that there is a “golden” opportunity to collaborate outside the health sector by working with the people driving the New Urban Agenda, who are actively engaged in helping city planners design the cities for the future all over the world.

During the discussion that followed Lindsay’s presentation, Jonna

Mazet, executive director of the One Health Institute at the University of California, Davis, asked Lindsay to elaborate on the success in Sudan and how the different sectors were brought together. She noted that tangible success stories are relatively rare in the One Health space, which involves collaboration among human, animal, and environmental health sectors. Lindsay explained that the Sudan National Intersectoral Committee for Vector Control had full political support, some financing, and an effective and dynamic person in charge and running the committee. He explained that they searched for and eliminated the location of the aquatic habitats; for example, they replaced leaking pipes that were relics of poor and aged British engineering. When they found that builders were not destroying the water supplies used for making cement on construction sites after the work was complete, said Lindsay, they took advantage of a bylaw outlawing this practice and went around the city destroying the water supply habitat. Similarly, he said that they required agricultural fields around the city to be free of water for a certain number of days each week. He added that they originally started to fine farmers who did not comply, which outraged the farmers, but when they explained the rationale for this decision, the farmers agreed to cooperate. Lindsay also said that they had a “malaria day” for schools in Khartoum, and schoolchildren were asked to find and eliminate a small aquatic habitat of some kind. Regardless of the sustainability or effectiveness of that intervention, he said, it was a worthwhile way to engage and communicate with the community.

Lindsay noted that his vision may be broader than the One Health concept—at least as it is construed in the United Kingdom, where it generally refers to veterinary diseases or infections coming from domestic livestock to humans. He said that he is interested in further understanding the infectious disease dynamics in populations of wild animals—not only domesticated animals—to better understand spillover events into humans. Mazet added that the implementation of large-scale One Health projects is sometimes impeded by the practical human nature problems and balancing concerns among different ministries.

David Nabarro, advisor for health and sustainability at 4SD, remarked that the multisectoral, interdisciplinary approach espoused by Lindsay is the same approach envisaged when the SDG agenda was first produced: a universal approach that applies anywhere in the world, involves interconnected thinking and action, includes all sectors of society during implementation, and involves partnering as well as integrated action. He suggested conceptualizing how to advance this approach. For example, he suggested that the work on Aedes-borne arboviruses and other vector-borne diseases could be linked to other activities—such as child nutrition or access to water and sanitation—without necessarily losing or weakening the emphasis on those particular arboviral diseases. Nabarro predicted that this approach,

in line with the SDGs, will be available in many more urban settings. He cautioned that overemphasizing vector-borne disease projects may constrain thinking. Instead, he suggested encouraging interdisciplinary and multistakeholder movements for health and seeking ways to integrate work on specific problems, like the arboviruses, to initiatives that are perhaps larger or differently shaped. Lindsay replied that his concern is overloading the system by making it impossible for committees to function and creating an unwieldy system by trying to do everything. He clarified that he is not trying to oversell Aedes-borne diseases, but to encourage people to reflect about what can be done in urban centers to reduce that risk as well as addressing other locally determined priorities.

BUILDING AN INVESTMENT CASE FOR HEALTH-PROMOTING URBAN ENVIRONMENTS

To explore strategies for building an investment case for upgrading slums and promoting health in urban environments, Siddharth Agarwal drew upon his work as director of the Urban Health Resource Centre in India. He said there is a large, disadvantaged, and increasingly urban population in India that contributes inexpensive labor to the growing economy of India. This population includes women and children, he noted, with child-bearing migrant girls facing particular risks. Agarwal explained that this group faces a host of difficulties in accessing education, social opportunities, and other services in slum environments and, in many cases, they have little awareness of the opportunities and services that are available to them. These disadvantages are compounded by restrictions on their freedom of movement and weak social networks, he added.

Agarwal maintained that it is critical to improve infection prevention in the slum environments where these types of disadvantaged populations reside and where pathogens thrive. He suggested that investing in the health and well-being of these slum populations benefits the urban area at large and contributes to national-level economic growth, because the urban component of the gross domestic product of many developing countries is growing faster than the rural component. By neglecting to address infectious disease transmission in slums, he noted that pathogens will continue to thrive, which will contribute to increased health care expenditures and a less productive workforce. Agarwal said that it can be difficult to finance investment in slums, either in the form of action research or time-bound funding, because there are so many unknowns and funders are often risk averse. However, he emphasized that these populations are living their lives at risk and argued that that they deserve a courageous approach to investment aimed at improving their lives.

Methods for Mitigating Infectious Diseases in Slums

Agarwal outlined a set of methods that have been implemented in India to mitigate infectious diseases in slum environments (see Box 5-1). He explained three methods to specifically help identify and assess slum conditions and inequities that would incite action. In the first method described by Agarwal, representatives from local women’s groups are engaged to assess living conditions across several slums using a qualitative adaptation of WHO’s Urban Health Equity Assessment and Response Tool (Urban HEART).3 With this tool, the women use color-coded dots to denote their assessment of each indicator. He said that this method drives action in slums, for example, by encouraging households to build low-cost latrines or encouraging hand washing with soap and water. Agarwal further described the method of spatial mapping of all of the listed and unlisted slums in a city. He highlighted the significance of identifying and mapping unlisted slums because, according to government estimates, around 50 percent of slums in India are unlisted (NSSO, 2010). He added that mapping of at-risk populations, including seasonal and recent migrant clusters, is an integral strategy of India’s National Urban Health Mission. Another method discussed by Agarwal is disaggregating data at the national and state levels to provide more insight into existing inequities and disparities in indicators,

___________________

3 WHO’s Urban HEART is available at www.who.int/kobe_centre/measuring/urbanheart/en (accessed February 10, 2018).

such as under-5-years-of-age mortality and living space density (which contributes to the transmission of infectious disease).

Agarwal also explained methods for communities to be active and take ownership in this issue. He described that gentle negotiation through community requests helps community groups to petition their local authorities and municipal corporations to improve the environmental conditions in slums by building water supply or sewage systems, for example. The groups are encouraged to maintain a paper trail and persevere with tact in their negotiations to receive the government resources for their communities, he said. Another method, said Agarwal, is to establish revolving community funds for health exigencies. Community groups manage their own revolving funds, he said, and they are trained to maintain records of loans provided for needs such as education, toilet construction, or starting a small business. He also added that the method to increase access to voter identification and proof of address for disadvantaged populations imbues people with greater power to express themselves to political leaders.

The final set of methods focuses on empowerment of vulnerable populations in India. Agarwal highlighted the approach of empowering women and girls in a largely male-dominated society. He suggested that empowering women by providing them with social support enhances their ability to care for themselves and their families, which in turn contributes to infection prevention in their homes and communities. Agarwal explained another method of encouraging women’s livelihoods, which focuses on providing women with vocational training, such as tailoring and stitching, selling vegetables in markets, or establishing slum convenience stores. This strategy provides women with additional resources to help care for the health and well-being of themselves and their families, he said. Finally, Agarwal highlighted the importance of empowering young people to enhance their self-esteem, improve their lives, and contribute actively to their communities. He suggested that investing in the next generation is especially relevant in countries like India, where the population of young people is enormous.

Agarwal reported that India now has an urban health policy in place, but its ongoing implementation has been slow. He noted that the policy encourages intersectoral coordination at both the municipal and community levels to promote overall well-being and health and to reduce the risk of infectious disease. He said that in some slums and informal settlements there have already been glimpses of improvement in access to services such as toilets, sewage lines, electricity supplies, water supplies, garbage removal, and paved streets. He described the specific example of a successful 5-year campaign by community women’s groups and youth groups that convinced civic authorities to build a permanent bridge over a large drain at the entrance to a slum, which directly improved the lives of 120,000 residents. Agarwal urged the group to take action toward infectious disease

prevention by focusing on building the capabilities and self-reliance of slum residents and providing them with a voice to change their circumstances.

FIT-FOR-CONTEXT WATER, SANITATION, AND HYGIENE INTERVENTIONS

In her presentation on fit-for-context WASH interventions, Daniele Lantagne, associate professor of civil and environmental engineering at Tufts University, opened by suggesting that the narrative around WASH needs to be changed. She explained that there tend to be two primary WASH narratives. The first is an urban high-income water narrative, she said, where there is piped, treated infrastructure that delivers water directly to people’s taps 24 hours per day, 7 days per week, and in which children are healthy and happy. The second is a primarily rural, low-income water narrative, she continued, in which people collect water from an unimproved open source and store it in a questionable storage container in the home. Within this second narrative, she said, there is a tendency to assume that providing WASH infrastructure is not yet feasible. This narrative focuses on strategies such as providing improved water sources, working with people to treat their water at the household level with chlorine or filters, providing a latrine to separate waste from the environment, and promoting hand washing. Lantagne suggested that slums do not fit neatly into either of those two narratives; she called for moving beyond those narratives to nuance and specificity for context.

Lantagne provided some historical context for WASH interventions. She explained that three types of organisms cause diarrhea at a general level: bacteria, such as those that cause cholera and typhoid; protozoa, such as Cryptosporidium and Giardia lamblia; and viruses, such as rotavirus and norovirus. She said that bacteria can be inactivated by chlorine and other disinfectants and that chlorine and other disinfectants can remove the bacteria and most viruses from water, but protozoan oocysts are chlorine resistant. She added that filtration can remove bacteria and larger protozoa from water, but filtration cannot remove viruses because they are too small. Treating water to remove all three of these organism types generally involves combined treatment of filtration plus chlorination, Lantagne said. She explained that combined treatment was the strategy used to successfully reduce infectious disease transmission across the United States and Europe during the “sanitation revolution” (approximately between 1890 and 1930). In Philadelphia, for example, she said that the number of typhoid cases peaked at around 10,000 in 1906, at which point drinking

water filtration began and drove a log reduction4 in the number of cases to around 1,000 within about 5 years. When chlorination of drinking water was introduced in the city in 1913, she added, it drove a further reduction in cases to just over 100 by 1930 (Matossian, 1997).

Urbanization, Slums, and WASH Infrastructure

Lantagne explained that the prevailing narrative was to replicate the type of combined WASH strategy used in Philadelphia by building infrastructure within developing, low-income countries. She said that infrastructure does create huge advantages, such as the widespread provision of reliable quality water, which leads to disease reduction and improved hygiene. However, she maintained that infrastructure is not appropriate for all contexts, because it requires political stability and large amounts of public funding. To illustrate, she said that the Deer Island wastewater treatment plant in Boston, Massachusetts, cost $4 billion to build and has operating costs of $300 million per year—the cost of sewage treatment in Boston is double the cost of its water, she added. She explained that infrastructure also needs land tenure that is located in conducive terrain, as well as population density and stability of population numbers—populations cannot be increasing or decreasing too quickly, she said.

Many slums cannot meet the prerequisite conditions for WASH infrastructure, Lantagne said. She explained that urbanization is driving increases in populations that are happening so quickly that it is difficult to install hard infrastructure to accommodate the rate of growth. For example, London urbanized from 1 million people to 6 to 7 million (roughly where it remains today) over a period of around 50 years between 1830 and 1890, which allowed time for infrastructure to catch up to the growth (Bairoch and Goertz, 1986). In contrast, Asia and Africa are rapidly urbanizing in the space of 20 years, with cities like Shanghai growing by at least 10 million people (UN DESA, 2015).

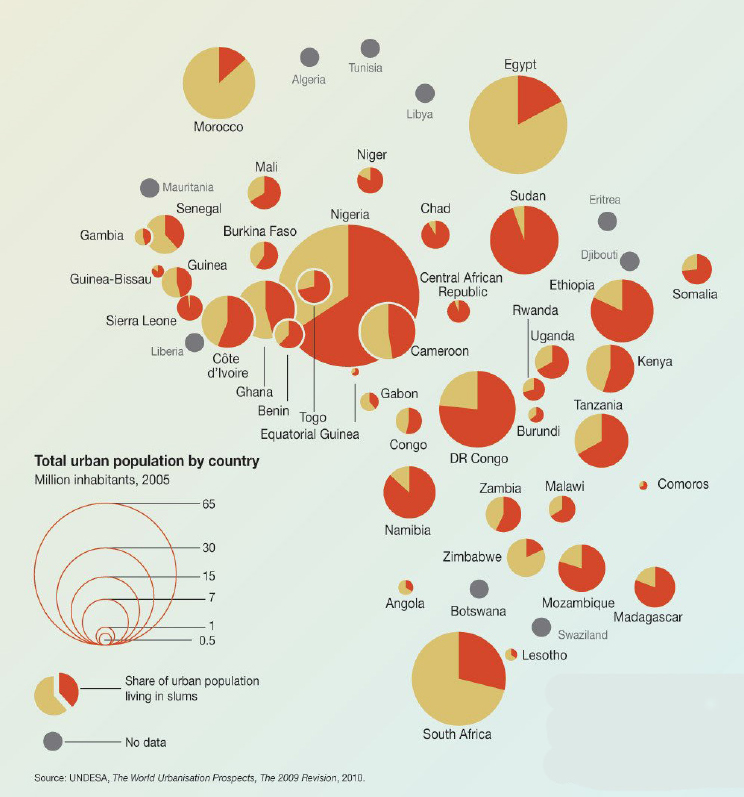

Lantagne noted that China is managing its urban growth through a top-down centralized scientific approach that includes rolling out identical water and wastewater treatment plants on a daily basis. However, in areas such as sub-Saharan Africa, some countries were unable to meet the Millennium Development Goal target of reducing by half the number of people without access to safe water and sanitation. In many of those countries, she said, three-quarters or more of their urban populations are living in slums with unknown land tenure (see Figure 5-2). She noted that the type of strategy used in China to roll out water and wastewater treatment

___________________

4 Each log reduction indicates a 10-fold reduction in colony-forming units of microbes; a 2-log reduction would further reduce colony-forming units by 100, and so forth.

NOTE: UN-HABITAT defines a slum household as a group of individuals living under the same roof in an urban area who lack one or more of the following: 1. Durable housing of a permanent nature that protects against extreme climate conditions. 2. Sufficient living spaces, which means not more than three people sharing the same room. 3. Easy access to safe water in sufficient amounts at an affordable price. 4 Access to adequate sanitation in the form of a private or public toilet shared by a reasonable number of people. 5. Security of tenure that prevents forced evictions.

SOURCES: Lantagne presentation, December 13, 2017; Pravettoni, UNEP/GRID-Arendal, 2011.

for rapidly growing populations is not yet feasible in many such places. She underscored the need to find ways to address slum populations in the interim until it is possible to build in reliable infrastructure.

Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene Interventions in Slums

Lantagne provided some specific examples of WASH programming and interventions in slums that have been successful in addressing water supply, water treatment, and the sanitation chain. She also described an example of a WASH intervention carried out in an emergency response context.

Water Supply Interventions

Lantagne said that water kiosks have been a success in improving water supply. She explained that the kiosk operators, who are typically in the commercial sector and not externally funded, usually obtain centrally treated water that is trucked in and stored in large containers. Water is typically sold to customers in 3-gallon containers, she said, and reported that these types of kiosks are now opening up in Haiti, Indonesia, and across Africa. She described a study in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, which found 1,300 kiosks in the city, over half of which had opened in the previous year, and most of which were obtaining water to sell from a franchise of four large providers (Patrick et al., 2017). She reported that 91 percent of the kiosks were selling water that met WHO standards for Escherichia coli. However, she noted that the expansion of kiosks gives rise to questions about the role of recontamination of water in households, about preserving water safety throughout the storage chain, and about the role of external funding. For example, she said, there are questions about how external funding should be used to leverage increases in water safety and whether increases in government regulations should be put in place to ensure safety throughout the water chain.

Water Treatment Interventions

Lantagne also described several successful water treatment interventions. In an ideal situation, she said, water is treated centrally, and the population receives water that can be used without further treatment. But when this is not possible, she added, water can be treated at the point of collection or at the point of use. She explained that as treatment becomes more centralized—that is, as it moves from point-of-use to point-of-collection to centralized water treatment—the amount of behavior change asked of the population decreases. More behavior change is asked of people who must

treat their own water at the household (point-of-use) or community (point-of-collection) level, she added.

According to Lantagne, the distribution of locally branded safe storage containers is an example of point-of-use water treatment that has been successful in urban and rural areas of Haiti that were affected by the earthquake and cholera. Each container has a tap and a liquid chlorine solution, she said, and they are distributed by community health workers. At the height of the cholera epidemic in 2010, around three-quarters of households (15,000 households) were reached with this program, but by 2014, the number of households reached had decreased to around one half (Wilner et al., 2017). Although this decline indicates a decrease in sustainability, she said, the program’s overall reach demonstrates that success is possible through community outreach and the use of appropriate products. However, she noted that it can be difficult to scale up such a program without large numbers of trained community health workers.

Lantagne described a program called Dispensers as an example of a point-of-collection intervention, as well as an illustration of how the same intervention can have different results depending on implementation quality in different settings. She explained that the program aims to reduce the need for behavior change by providing a tank of chlorine next to a community source of water, so that people can treat their water when they collect it. She reported that the program was evaluated in different emergency contexts in Haiti, Senegal, and Sierra Leone, with results highlighting the importance of context and implementation. Two countries (Sierra Leone and Haiti) had almost no use of the program, while Senegal had almost 100 percent use (Yates et al., 2015). She suggested that this disparity was caused by a set of implementation factors, such as having experienced staff, having appropriate training, having materials in the right language, and ensuring that the dispenser’s engineering was functional. She cautioned that there are no silver-bullet interventions in WASH, only interventions that are appropriate for a specific context and that must be implemented well to be successful.

Sanitation Chain Interventions

To discuss successful sanitation chain interventions, Lantagne explained that people with access to modern sewage systems have the benefit of not having to deal with their own waste—it is flushed down a toilet and passes through a treatment plant and is shipped away. Within such a system, she said, large amounts of wasted clean water and large amounts of nutrients from urine and feces are not repurposed for agricultural use. In places without a modern sewage system, she explained, people rely on a sanitation chain of collection, treatment, and reuse.

Lantagne described the Fresh Life program in Kibera of Nairobi, Kenya,

which provides central facilities for people to defecate.5 The waste is collected in buckets and trucked to a waste facility treatment plant, she said, where recovered nutrients from the waste are eventually used in agriculture and, to a lesser extent, the waste is used to generate electricity. She added that Sanivation, another program in Kenya, uses a model of customer-oriented waste collection. People who join the program receive a type of home toilet and have their waste collected from the home regularly, she said, and the waste is treated using ultraviolet light and heat to transform it into briquettes sold as affordable fuel for cooking.

Emergency Response Interventions

Lantagne described emergency response work carried out with a WASH cluster in Syria, where more than 95 percent of the population had access to pipe-treated safe drinking water and sanitation in 2009. The conflict caused a rapid decline in access to the network water source, she reported, from 22 percent in 2016 to 15 percent in 2017 (Sikder et al., 2018). She noted that access varies by subdistrict, and in some areas the infrastructure is being deliberately targeted for destruction. She explained that Syria also has a private trucked water network that sells water. The majority of the population is now dependent on trucked water, she said, and the proportion of the population dependent on trucked water has increased from 77 percent of the population in 2016 to 83 percent of the population in 2017 (Sikder et al., 2018). In an effort to improve the safety of trucked water, she said, a United Nations Children’s Fund intervention is providing chlorine to treat the water that is being delivered. According to Lantagne, a barrier the intervention has faced is getting the chlorine across the border into the country.

Suggested Ways Forward

Lantagne closed by recapitulating her call for a paradigm shift in the WASH narrative. She suggested moving beyond the existing WASH narratives to reach people in slums and focusing on the provision of decentralized WASH services in areas without hard infrastructure. These efforts could be strengthened, she said, by providing the necessary training and education to the people implementing the programs, as well as to the program recipients. She also suggested supporting private-sector initiatives—particularly within water interventions—to be able to achieve sufficient scale. Moving forward, there are short-term questions about decision making for interventions, she said, and longer-term questions about how to ensure programs’

___________________

5 Sanergy manages Fresh Life programs in several informal settlements in Nairobi, Kenya.

sustainability over time and how to establish hard infrastructure where it is lacking. She suggested a dual focus on both the short- and long-term issues.

ENGAGING COMMUNITIES: FROM SURVEILLANCE TO POLICY

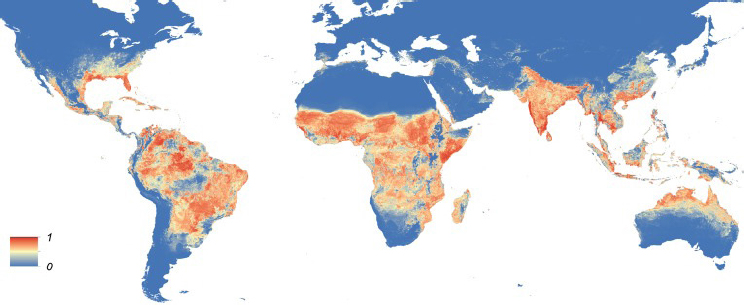

Eva Harris, professor of infectious diseases and director of the Center for Global Public Health at the University of California, Berkeley, offered her vision of the concept of engaging communities in addressing Aedes-borne arboviral diseases, such as dengue and Zika. Her presentation focused on an experience with community engagement in a pilot program that led to a large-scale trial, but she began by discussing the particular threat posed by Aedes-borne diseases. She reported that mosquitos kill an estimated 725,000 people each year worldwide, killing more people than other humans (475,000), snakes (50,000), and rabid dogs (25,000) (Gates, 2014). The Aedes aegypti mosquito is distributed widely across the globe, she noted (Kraemer et al., 2015) (see Figure 5-3). The Aedes mosquito population grows and their larvae develop in clean water around people’s homes, she explained, and its proliferation is compounded by the behavioral ecology of 21st-century urbanization in tropical cities, especially issues of water and garbage management. Although there are a few notable examples of successful vector control to prevent Aedes-transmitted diseases, they have been difficult to sustain (Achee et al., 2015; Morrison et al., 2008; Wilder-Smith et al., 2017), and many programs have focused primarily on chemical control, which to Harris, have been problematic because of possible unintended health effects. As efforts in vector control have been insufficient, dengue, Zika, and chikungunya viruses continue to spread worldwide.

Changing Attitudes Toward Community Involvement in Interventions

To strengthen vector control efforts, Harris has been exploring ways to include communities in controlling the Aedes vector. Harris said that there has historically been somewhat of a bias against community involvement interventions; she suggested that this may be from a lack of data about their effectiveness, as it can be difficult to measure and quantify the effect of such programs. For example, she reported that a 2007 review found only weak evidence that community-based dengue control programs alone and in combination with other control activities can enhance the effectiveness of dengue control programs (Heintze et al., 2007). However, she noted a shift toward recognizing that communities can be involved in a productive way. She cited a meta-review which concluded that the best practice when designing interventions is to use a community-based integrated approach

NOTE: The map depicts the probability of occurrence (from 0 blue to 1 red) at a spatial resolution of 5 km × 5 km.

SOURCES: Harris presentation, December 13, 2017; Kraemer et al., 2015.

tailored to local epidemiology and sociocultural settings and combined with educational programs (Erlanger et al., 2008).

The paucity of research on this topic gives rise to questions about how to engage and motivate communities effectively, said Harris. To explore this, she described a couple of initiatives that have been implemented over the past decade that are variations on the theme of community-based participatory research. She explained that the Special Program for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases carried out an eco-bio-social initiative between 2006 and 2011 to support work on the control of vector-borne dengue in Asia and Chagas disease in Latin America (Gürtler and Yadon, 2015; Sommerfeld and Kroeger, 2012). She reported that the initiative led to new country-specified approaches and research outputs. The Pan American Health Organization’s EGI-Dengue concept6 promotes an integrated approach that includes a social communication component, she added. In Cuba, she reported that researchers used a structured format to investigate a more vertical approach to community involvement in dengue vector control using randomized controlled trials, which they found effective in embedding community empowerment strategies into routine vector control programs (Castro et al., 2012; Vanlerberghe et al., 2009).

___________________

6 Commonly referred to by its Spanish acronym EGI-Dengue (Estrategia de gestión integrada) but is also known as the Integrated Management Strategy for Prevention and Control of Dengue. It is available at iris.paho.org/xmlui/handle/123456789/34860 (accessed March 8, 2018).

Applying the Camino Verde Approach for Sustainable Control of the Aedes Vector

Harris said that efforts are now oriented toward taking community engagement concepts that have been defined over the past 10 to 15 years and combining them with technology tools to allow real-time data to be captured. This allows for communities to autonomously measure and be motivated by their own progress, she said, as well as making the information collected available for reports and for country-level analysis. To illustrate such an approach, she described the Camino Verde (“Green Path”) initiative, which was designed to prevent dengue and to examine community mobilization for sustainable control of the Aedes vector.

Camino Verde uses an epidemiological framework and methodology that had been applied in 50 different countries over 30 years to measure and to bring community data into policy, explained Harris.7 It also incorporates the care group model approach, she said, in which facilitators work with community volunteers, who in turn work directly with individual households and residents (Perry et al., 2015). In Camino Verde, she said, the care group model was adapted into a strategy called socializing evidence for participatory action (SEPA), which was then applied to the dengue problem in Nicaragua.

Socializing Evidence for Participatory Action

Harris explained that in Camino Verde’s SEPA strategy, small community teams formed groups called health brigades (Brigadas SEPA) and received training in pesticide-free vector control. Community leaders (brigadistas) then visit households to educate people about the threat of dengue and the life cycle of the Aedes mosquito, she said. Harris argued that the best way to engage and motivate communities is with their own data and evidence. She said that, rather than giving instructions, it is better to help communities identify their own evidence for a problem—for example, larva in water near the home—and figure out how to solve it. She maintained that this is more effective because community members are more engaged with the knowledge and with their own solutions to their own problems.

Harris explained that the SEPA strategy has three levels of intervention to help engage and motivate communities: house interventions, within-neighborhood (barrio) interventions, and interbarrio interventions. She noted that public health interventions often instruct people to get rid of mosquitos in and around their homes by eliminating standing water, clean-

___________________

7 Details about Camino Verde are available at caminoverde.ciet.org/en/sepa (accessed February 10, 2018).

ing storage barrels, and applying other methods, but she suggested that this does not provide people with real motivation to carry out those onerous tasks. As part of Camino Verde, reported Harris, they held discussions with community members who told them that they wanted the underlying knowledge to understand why those kinds of actions are needed. To address this request, said Harris, the program began a campaign to educate people about the mosquito life cycle (from eggs to larvae to pupae to mosquito in about 8 to 10 days). She said they explained to the community that taking action to eliminate breeding sites just once every 8 days can cut the mosquito life cycle without using pesticides or chemicals. This type of explanation made sense to people, said Harris. Because they understood the rationale, she added, they were no longer offended that they were being asked to get rid of the old tires they owned. This in turn generated community-led solutions, she noted, such as filling these old tires with dirt to create stairways, bridges, or planters. Harris also described some of the program’s barrio-level interventions, such as reducing key breeding sites in public areas, hosting barrio fairs and cleanup campaigns, and engaging schoolchildren in educational activities and games.

Camino Verde Pilot Phase

Harris reported that during Camino Verde’s pilot phase they carried out an observational study in Nicaragua through a tripartite cycle of evidence gathering, analysis/planning, and intervention that was repeated and refined over 4 years (2004 to 2008). She said that evidence was obtained through entomology to gather knowledge of mosquito breeding receptacles, through surveys of knowledge and behavior, and through serology to measure antidengue antibodies in children’s saliva. She explained that the latter is a noninvasive epidemiological approach to quantify infection rates; measuring infection is useful, she said, because people with asymptomatic infection are at higher risk of developing more severe disease when infected for a second time.8 During the analysis and planning component, she said the data were analyzed and the evidence was relayed back to the community during discussions. Communities were heavily involved in the intervention component, she added, by using the evidence they were provided to create their own mosquito control strategies, communication strategies, and neighborhood brigade activities.

Harris reported that the lessons learned from the pilot phase formed the basis of a large cluster randomized controlled trial in two countries that quantified the effectiveness of community mobilization for dengue

___________________

8 Paired samples gathered before and after the epidemic were used to examine the increase in antibody titers.

prevention as part of its methodology (Andersson et al., 2015). According to Harris, the following key lessons were identified:

- Evidence is critical for dialogue and reflection with residents that risk exists in their own homes, that they can control the vector in their own environment, and that integrated neighborhood action is needed.

- Socialization and dialogue about the evidence at the household and neighborhood levels can generate interventions from a cost–benefit perspective.

- Beyond motivation, the SEPA process aims for households and communities to responsibly assume control of their own health—prevention is an empowering approach.

- External actions are generated from the knowledge and experience of the communities themselves; there are no fixed, one-size-fits-all solutions; the practice is specific to each neighborhood.

- Every community is a vast microcosm, but there are certain common principles. Rather than issue instructions, provide communities with evidence and concepts they can translate into action in a way that makes sense for their own community.

- Community responsibility materializes organically; effectiveness and sustainability depend on local management and autonomy of SEPA brigades.

Camino Verde Cluster Randomized Controlled Trials

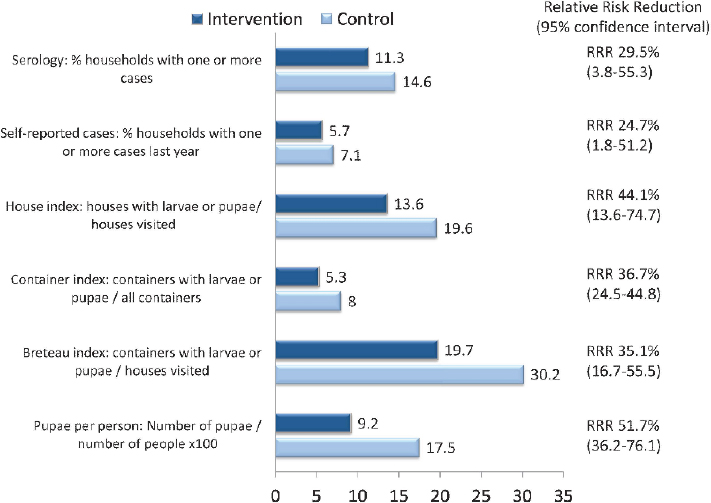

Harris explained that the parallel cluster randomized controlled trials were carried out among 85,000 total residents from two sites in Nicaragua and Mexico,9 and the study included double randomization, interventions, and impact measurements. She said that the primary outcomes were incidence (antidengue antibodies in saliva) in children 3 to 9 years of age, entomological indices, and self-reported recent dengue cases. She reported that, for the primary outcomes across both countries, they found a 29.5 percent decrease in the serological indicators, a 24.7 percent decrease in self-reported cases, and decreases between 35.1 percent and 51.7 percent for entomological indices (see Figure 5-4). She reported that secondary analyses found a 25 percent protective factor from the intervention. It also found that use of the larvicide temephos in water storage containers actually increased the risk of dengue. They surmised that the ministry of health may

___________________

9 The two sites were the urban city of Managua, Nicaragua, which has a tradition of community organization, and three coastal regions of Guerrero, Mexico, which includes the Acapulco urban area and the rural areas of Costa Grande and Costa Chica.

NOTE: RRR = relative risk reduction.

SOURCES: Harris presentation, December 13, 2017; data from Andersson et al., 2015.

use temephos in households with notified dengue cases, she added, but the same increase in risk was found in households that had no reported dengue cases. She reported that the same results—decrease in risk with intervention and increase in risk with use of temephos—were obtained over 7 years of the observational pilot study. Social mobilization has been an added value of the intervention, according to Harris. She said that communities have mobilized to have sewer lines placed, for example, by counting the number of barrels and presenting that to the mayor’s office. This in turn provides a platform to mobilize on other issues such as domestic and sexual violence, she added. Dengue is the banner, Harris said, but the ability to mobilize on other issues is actually more important to the communities.

DengueChat for Real-Time Capture and Use of Data

Harris reported that they have taken the concepts learned from the Camino Verde and added a technological tool that captures real-time data:

The DengueChat Web– and cell phone–based platform. She explained that the cell phone–based system enables community participation as well as data generation by facilitating the reporting and eliminating of mosquito breeding sites, and community mapping. It also facilitates data capturing through household surveys, socioeconomic status data, and real-time, crowd-sourced community entomology, she said. The accompanying Web-based system allows for communication and dialogue as well as providing specific information for households to use, she added.

A DengueChat user finds a breeding site, takes photographs to document it, then receives points for eliminating it, Harris explained, with the advantage that the information is mapped and the breeding site is destroyed at the same time. This has given rise to “dengue warriors” who compete against each other both individually and as communities, she said. A DengueChat pilot study was carried out in late 2014 and early 2015, she said (Coloma et al., 2016). She reported that pre- and postintervention larva measurements indicate that the brigades kept the work going after the intervention ended in barrios that received the intervention, and those barrios had much lower larva levels than the reference communities almost 2 years later. DengueChat pilots and programs are ongoing in Brazil, Mexico, Nicaragua, and Paraguay, she said.

Harris highlighted the role of community action and community participation in research and data generation in moving toward sustainable models of community engagement. She said there is tension between vertical and horizontal programs, noting that programs have to be housed somewhere, but they also have to be horizontal to work well. She also suggested that a challenge moving forward will be to find ways for ministries of health and community organizations to work together with health, municipal services, and community organizations operating within a complex, integrated, and intersectoral model. She concluded by maintaining that evidence-based actions and policies are critical to first making programs successful and then being able to bring them to scale.

DISCUSSION

David Relman, professor of medicine at Stanford University, asked Harris about what local community members understood to be the measurable goal that was relevant to their daily lives from her studies. Harris responded that they communicated to community members that dengue was a problem that could be addressed by cutting the life cycle of mosquitos to prevent the virus from being transmitted. She said they explained that a person can be infected with dengue but not be sick and that when there is another infection it can be worse. Harris said that showing people that their own children had dengue infection was power-

ful and catalyzed community engagement in understanding the mosquito life cycle and why breeding sites need to be eliminated—many community members became citizen scientists through this process, she said. They also solicited testimonials, she added, such as, “My son had dengue hemorrhagic fever and it was very frightening,” or “My brother died of it.” Harris emphasized that the communities were engaged because the community collected evidence including larvae and pupae in their own homes, as well as test results indicating whether their children had the infection, even if the children were not sick.

Relman followed up by asking if there were general features of those measurable goals that made them particularly compelling for the local populations. Harris replied that since the large-scale trial has finished, the focus has shifted to entomological evidence that does not require serological analysis in a laboratory. More broadly, she said, the focus should be on tangible evidence that people can measure and use to track progress, but this will vary according to what the intervention is targeting. In that context, Lantagne noted that WASH does not have a similarly tangible goal as the elimination of mosquito breeding sites. She said that treating water reduces the number of diarrhea cases in children under 5 years of age by half, but fewer diarrhea cases is not as strong of a driver in WASH as the fear of cholera. Much of the desired behavior change has been seen around cholera outbreaks and epidemics.

Lantagne also mentioned that when behavior research was conducted, common responses to the reason for behavior change included statements that denote aspirational thinking, such as, “I have a good family, I am going to take care of my children, and I want to provide my guests something nice.” She also provided an example from Haiti where people like the tap on the safe water storage container because it makes them look as if they have flowing water in the household. However, she noted that the triggers for aspiration-motivated behavior change will vary for different cultures and interventions. On the other hand, she remarked that there is ethical debate in sanitation over using the disgust reaction as motivation.

Agarwal described his efforts to work with a population of about 300,000 people spread across 54 slums, collecting qualitative community-level outcome indicators that can be measured over time to demonstrate progress. For example, he said a community would be assigned a color-coded dot (green, yellow, or red) that indicates the proportion of households that have toilets in a community or the proportion of households that have an adequate water supply for general use. Agarwal said they use similar outcome indicators to measure the work of community groups as well as for governance purposes (for example, to indicate whether the community was exercising its power and entitlements to demand assistance

from the government). These are important measurements that can propel immediate action.

Peter Daszak, president of EcoHealth Alliance, wondered how the presenters have dealt with governments that oppose or disenfranchise some populations that are purposefully pushed to live in slums or low-income settings due to ethnicity, political ideology, class, or immigration status. Agarwal responded that his program initially faced opposition from the government for using the phrase “illegal slum” instead of “listed slum,” for example. He said that after extensive meetings over time, they were able to help shift some of the thinking at the government level, which has now become part of the National Urban Health Mission. Lantagne remarked that, in her experience, governments are resistant to reporting to WHO diseases such as cholera, regardless of the population affected. Such tensions move back and forth, she noted, and suggested that efforts need to align within that to understand where the balance is. She continued that this type of imbalance is evident in some refugee camps in places like Kenya, where the governments provide refugees with the minimum amount of water for human survival and the refugees provide the government with host-country status and the consequent funding and political will.

Nabarro asked why the types of approaches described by the presenters are not happening everywhere. He hypothesized that one issue is the need to change the narrative and suggested that it should be a collective responsibility in this work to help build a methodology that centrally includes shifting the narrative, which applies to health and beyond. For example, he suggested shifting the language from the concept of telling people top-down about how to change behaviors to the concept of helping to enable and empower people. He posited that this amounts to a move from instructing to engaging, from engaging to encouraging participation, and from encouraging participation to stimulating ownership and local management. He suggested that programs might explicitly include a focus on trust building with local authorities as well as conveying that a given program is not a tool for local authorities to manipulate. Nabarro also suggested that, for an approach to be widely adopted, it is important to have a clear methodology that can be taught and learned. Lantagne added that this type of shift is reflected in the language that is becoming more widespread in emergency response now: rather than the cost-prohibitive mass provision of water filters, for example, the approach to an emergency has shifted to finding an inflection point or nudge, such as how to get chlorine into the country to treat the water trucks. She noted that the term compliance implies that “those poor people didn’t comply with me and treat their water,” and said that it is essential to move toward understanding the community and its potential nudges. Harris said that in both Mexico and Nicaragua they carefully mapped out the so-called SEPA strategy, which identifies and illustrates

how to approach the critical pieces in each country. In terms of changing the narrative, she said that in vector control there is an openness to new strategies to supplant those that are not working, as well as an openness to having the community be part of the story. She noted that governments tend to be vested in standard approaches because, even if they are not effective, they demonstrate that something is being done to deal with an epidemic. Another problem, according to Harris, is the heavy financial investment of industry in those standard approaches, which she said gives rise to larger meta-political and economic issues. Lindsay suggested that these interventions can also be seen as development, which contributes to improved health. Agarwal added that, in his experience, it is important to work collaboratively with communities and local authorities; to use the appropriate polite, nonconfrontational language; and to make materials and meetings specific and focused.

Edward You, supervisory special agent in the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Weapons of Mass Destruction Directorate, asked Harris if they measured potential financial or other impacts from decrease in disease. Harris said that some of the data captured include how many days someone was out because of their sick child or themselves. She added that the motivation behind new barrios taking part in the large trial came from a cost study and focus groups that showed the amount of money spent on mosquito control, which triggered looking for effective alternatives.

Umair Shah, executive director of the National Association of County & City Health Officials, asked about engaging the marginalized to imbue resilience and positivity in a bidirectional way toward a common understanding of health. He also asked about how to translate some of the work from global settings to domestic settings in the United States. Harris replied that they have created a platform similar to DengueChat, called ZikaChat, which includes a mosquito control component as well as tools and information about how to deal with Zika and pregnancy. In the San Francisco Bay Area, she said, there are efforts to engage communities in mosquito abatement, and she reported that there has been receptivity on the local domestic side for incorporating some elements from global health that make sense in this domestic environment. Lantagne said that work done in decentralized WASH in emergencies in developing countries has been brought back to the United States when there is an emergency, such as the necessary use of household water filters in Flint, Michigan, caused by infrastructure problems. She noted that some types of interventions not previously distributed in the United States are now being used for short-term interventions after hurricanes, for example.

In the larger sense, Lantagne remarked, people are beginning to question how long the U.S. water and sewer infrastructure can be maintained in order to meet the regulations for new chemicals each year while continu-

ing to provide 150 gallons per person per day of quality drinking water to every individual in the United States. She suggested that if practices such as watering lawns with drinking-quality water are not changed, then there may be a secondary sanitary revolution to contend with, especially with the advent of more emergencies related to climate change and infrastructure.

Albert Ko, professor and chair of the Department of Epidemiology of Microbial Diseases at the Yale School of Public Health, asked whether latrines are a viable long-term solution for urban slum populations, especially in megacities. Lantagne replied that latrines do not make sense in urban slums because of the issue of space for sludge disposal. There are also concerns about their viability in rural areas, partially because children tend to be afraid of latrines, and their feces end up on the ground. Furthermore, she noted that, even though latrines isolate waste from the environment, the people handling the waste have increased risk of disease and transmission. She suggested that the narrative should be changed away from latrines in general and toward other options, such as providing people toilets and collection or providing centralized places to defecate.

Ko remarked that in situations of poverty or when high negative health externalities are present, it is difficult to think of approaches that do not include subsidies or conditional cash transfers in the implementation pathway of trying to increase coverage. Lantagne replied that emergency response and development are both moving in the direction of conditional or unconditional cash transfers, because giving cash is efficient and it stimulates the local economy.

Emily Gurley, associate scientist in the Department of Epidemiology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, asked whether technology could help facilitate communities in collecting their own data and in monitoring their own exposure and health status, noting that some communities are already monitoring their own air pollution. Lantagne said that there is a significant move toward funding new technologies for rapid water testing, because the current limitation is that most of the ways to test this require either a culture or polymerase chain reaction, which both take time.

As moderator of the session, Corburn synthesized some of the concepts he gleaned from the presentations. Questions to address moving forward, he said, include how to move from research into action, policy, and intervention as well as what to do, for whom, how to do it, and how to assess what is working. He noted that the presentations emphasized the role of community members as experts, not just in consultation for research but as active contributors to identifying problems, collecting and analyzing data, moving toward solutions, and evaluating progress. Communities and cities are complex systems rather than monocultures, he reflected, and suggested that integrating local expertise and knowledge could help to better under-

stand risks and effective interventions. Corburn said that slums should not be approached in the context of only one exposure, behavior, or risk at a time; he suggested making the eco-bio-social-cultural interaction explicit in this work and considering how people and places co-constitute risk exposure. He remarked that the problems at hand are too complex and challenging to be addressed by a priori models and solutions; he added that community engagement can be integrated with building robust monitoring, tracking, and data feedback systems to allow for continuous adjustment. Finally, Corburn suggested that linkages between policy and local, urban, and community-scale projects appear to be a critical piece in moving to health equity.

This page intentionally left blank.