3

Bridging the Education-to-Practice Gap

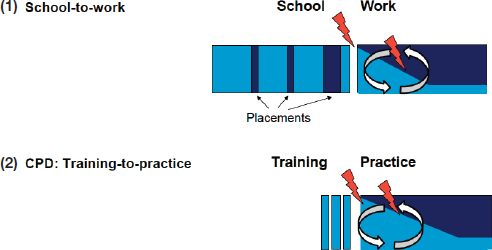

Leveraging existing technologies, as discussed in Chapter 2, is one element in the transformation of health professions systems. Specifically, the gap between education and practice can be addressed by means of digital media. Pimmer introduced the session by describing the education-to-practice gap and the variety of forms it takes. He said there are three main situations in which the gap is most evident: in placements during school, in the first job after graduation, and in the training-practice transfer of continued professional education and training. Students who are experiencing the workplace for the first time often learn that what they were taught in the classroom does not correlate well with the realities of the practice setting.

They may find their education has not prepared them appropriately for the work they are expected to do and may need extra support to stay engaged. The first 6 to 9 months are a particularly “critical phase” that affects the professional development, retention, and career success of young health professionals. In addition, the third gap exists where health professionals find that their continuing professional development training does not translate into day-to-day practice (see Figure 3-1).

This chapter covers three different uses of technology, used at three different stages of a health professional’s career. First, Paul Worley, National Rural Health Commissioner for Australia, talked about how Flinders University has used technology to support and train health professions students in remote and rural areas of Australia. By training students in these real-world environments, students become aware of the challenges, are better integrated into communities, and are better prepared to practice once they graduate. Second, Pimmer addressed the challenge that health care providers face when first entering practice in rural and underserved areas, and how social media can be used to support and empower such providers. Third, Cynthia Walker, vice president at Medtronic, discussed the use of two technologies—augmented reality and interactive video—to engage, immerse, and train practicing health care providers on new procedures.

NOTE: CPD = continuing professional development.

SOURCE: Presented by Pimmer, November 17, 2017.

BRIDGING THE GAP THROUGH EDUCATION IN RURAL COMMUNITIES

Paul Worley, former dean of medicine at Flinders University and now National Rural Health Commissioner for Australia, spoke to participants about his work in Australia on bridging the education-to-practice gap. Worley painted a picture of the challenges facing Flinders University medical school in 1997: the area it served was a landmass four times the size of Texas with only 2 million people, there were severe doctor shortages outside the capital city, and life expectancy was similar to sub-Saharan Africa in some areas. Worley said that improving this situation required engaging in teaching and research in the underresourced regions, recruiting students from these areas, sending students to work in regions with low human health resources, and establishing a flourishing academic culture in the health sector. However, the full academic infrastructure of the university could not be replicated in each small town, so a solution involving distance learning was needed, said Worley. The Flinders University department that focuses on distance learning existed long before smartphones, widespread Internet access, or video conferencing. Instead, at first they used low-tech approaches such as photocopies, faxes, and videotapes to reach students. The distance learning program began with students in a small geographic region, fairly close to the capital city of Adelaide, but it eventually spread over the entire 3,000 miles between Adelaide and Darwin.

Worley said that this distance learning program was enormously successful in a number of ways. They found that clinicians in the rural communities where students were learning were using the equipment and information for their own education and clinical purposes, thus multiplying the effect of the program. Students “had profound academic outcomes as a result of learning in context” of these rural communities. Students were enabled to live in rural communities while studying, and often chose to remain in these communities as primary care rural practitioners after graduation. While some students chose other specialties, the rural and remote learning students were 17 times more likely to choose rural practice compared to students who learned in cities. Using technology to connect these students to the resources of the university allowed students to stay in the communities long enough to understand the issues and believe they can make a difference. Finally, the students studying in these rural communities are valuable to patients as part of the health care team. Worley emphasized that this model is not “medical tourism” but is “actual, real work” that benefits the community and patients while also delivering education in rural and remote areas.

One of the benefits of distance learning, said Worley, is the ability to scale up clinical education by enabling clinical venues to become educational venues. It has also opened up a career pathway for rural clinicians by allowing

them to be part of the academic team. For example, the director of their medical program works 3,000 kilometers from the main campus. The program is somewhat of a reinvention of an apprenticeship program, said Worley, allowing rural practitioners to become teachers, and allowing students to learn in the context of day-to-day practice. Using technology as an adjunct to the apprenticeship model, said Worley, ensures that students are able to access accurate information and can be evaluated on their knowledge and skills.

This distance learning approach will become increasingly necessary as the global requirement for health workers increases, said Worley. Some estimate that the world will need 18 million more health workers by 2030 (BMJ, 2016). “We can’t train all of those people in the large quaternary hospitals in our major cities,” he said. Students will have to be trained in rural and underserved areas because those are the areas that lack health professionals, and we need technology-enabled education in order to link these students to resources and information. Worley told participants about a book called Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships: Principles, Outcomes, Practical Tools, and Future Directions (Poncelet and Hirsh, 2016). The final chapter envisions a future system in which communities and health services are the drivers behind health professions education. Universities are seen as a partner and an adjunct, but they are partnered with local health organizations to build a grassroots, community-based approach to education.

DISCUSSION

Cox asked Worley for his perspective on how to spread this type of educational model throughout an entire country, noting the establishment of several similar regional programs in the United States. Worley responded that in his view, this model has to be driven by communities. He said that in 1997, he was a rural doctor living in a rural community and saw the need for a new model of medical education. He worked within his community to lobby for the money and resources to start the program, and it has now expanded across Australia. Twenty-five percent of medical students in Australia now undertake at least 1 year in a rural, regional, or remote community using technology to facilitate this experience, said Worley.

Julianne Sebastian asked Worley to comment on the state of today’s technology, and whether it is adequate to meet the needs of these types of programs. “I don’t believe that technology is limiting us right now,” said Worley. “I think we have the technology. We don’t have the will.” Worley explained that there are structural forces and institutional inertia that are maintaining the status quo in education and health service delivery. There are, of course, issues with bandwidth or access to technology; people in rural areas may not have the bandwidth to support high data synchronous communication. However, Worley said, these issues do not necessarily

present a barrier. The Flinders distance learning program began with low-tech asynchronous communication, he said, and texting—a low-bandwidth asynchronous form of communication—is far more popular than FaceTime. Worley noted that while students in rural areas with low bandwidth may not be able to interact in real time with experts at the university, they have found that there is a great deal of expertise outside the university that students can take advantage of.

Laura Magaña Valladares, a forum member from the Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health, asked if this model could be expanded to include other health professions and to educate people as part of an interprofessional team. Worley said that a major barrier to this is that most health professions students have to be supervised by a member of the same profession (e.g., a speech therapy student has to be supervised by a speech therapist). In most of these rural areas, there are few if any specialists to serve as supervisors. This is an example of the institutional inertia that has to be overcome in order to expand this model further, said Worley. Worley did note that despite these barriers, students studying in rural areas are finding ways to get together with students of other disciplines and to solve problems together. “Rural and remote practice is a team sport,” said Worley, and students are empowered to make these connections and build the interprofessional education they need.

Following up on this discussion about a lack of specialists in rural areas, Thibault asked Worley how the medical college works to produce and support medical specialists to serve in rural areas. Worley said that while 60 to 70 percent of medical students in the program go into primary care, the remaining 30 percent go into specialties such as surgery, obstetrics, and psychiatry. Working through the colleges and their accreditation systems, these students are encouraged to be “generalists” within specialties, said Worley, meaning that while they specialize in one area, they have broad knowledge about a range of issues within their specialty and can meet the needs of many different types of patients. For example, a surgeon working in a rural area will not specialize in one type of surgery, but will be a general surgeon able to perform many types of surgery. These specialists will spend some of their time training in the large urban hospitals, but like their primary care colleagues, will spend the majority of their time training in the rural and remote areas, enabled by technology.

BRIDGING THE GAP THROUGH SOCIAL MEDIA

Pimmer told workshop participants about efforts to use mobile social media to support new health care workers in parts of the world that are underserved by traditional professional networks. Pimmer said that two of the educational key challenges in these regions are that health care work-

ers have little access to up-to-date information, and they often work in professional isolation. For example, community health workers frequently work alone in their communities and have limited connections with other health workers or their supervisors, even in the first few months after training, which are a “particularly critical phase” (see Figure 3-2). This situation restricts the workers’ opportunities for professional development and professional satisfaction, and it can result in attrition if workers are not supported. Because social media is already in the hands of many of these workers, it can be used for educating, training, connecting, managing, and supervising health workers and professionals, Pimmer said.

The research that Pimmer described analyzed the use of WhatsApp (a popular messaging app) to improve knowledge and skills and professional connectedness of nurses in rural communities in Nigeria, South Africa, and Zambia. The findings suggest that the informal use of this instant messaging platform alone was associated with higher levels of professional social capital, the development of a professional identity, and with reduced feelings of isolation from professional communities (Pimmer et al., 2018).

Specifically, the intervention sought to give nurses access to knowledge resources and to create and strengthen professional networks. To do so, WhatsApp groups were created with newly trained nurses; the group held moderated peer-to-peer discussions, including the circulation and discussion

SOURCE: Presented by Pimmer, November 16, 2017.

of relevant clinical knowledge. In addition, the intervention sought to spark discussions and reflections among the nurses about their professional journeys, including successful moments as well as hardships. The interventions were maintained for 6 months. Pimmer said that preliminary findings show use of the WhatsApp interventions resulted in higher levels of knowledge and fewer feelings of professional isolation compared with the control group. One interesting finding, said Pimmer, was that participants who were active contributors to the group (versus passive “readers”) were more strongly and positively affected by the intervention. This has significant implications regarding the moderation of the group, which needs to be activating and make participants share their own experience. Pimmer noted the major advantage to this type of intervention is most health care workers, particularly nurses, already have smartphones or advanced phone features and are comfortable with these types of apps. While social media apps may not be the gold standard for education, the fact that many health workers already have access makes the intervention scalable and sustainable.

In addition to small and bounded groups, Pimmer also gave an example of the use of a massive social media environment, which served as a rich reservoir for learning and professional development: a Facebook site for medical students and professionals that has more than 90,000 followers from across different Asian countries including India and Nepal (Medical Profession, 2018). The members of this Facebook group share learning resources and information, such as quiz questions and minicases, and hold discussions about professional roles, norms, and values. Interestingly the group is not tied to any institution, but is a bottom-up effort that is maintained by a local doctor (Pimmer et al., 2012).

One downside to social media, said Pimmer, is that it can be a vehicle for spreading disinformation and rumors. Pimmer said that fostering a sense of “digital professionalism” among health professionals would help mitigate this problem (Pimmer and Tulenko, 2016). He noted that his organization is working on developing resources for digital professionalism, but he is not aware of any existing framework in the domain of health professional education for this purpose. Based on his experience and research, Pimmer concluded social media interventions for health care professionals should use peer moderators who are close to the participants; should encourage active participation through games, contests, or quizzes; and should personalize the intervention by facilitating personal reflection and learning.

BRIDGING THE GAP THROUGH PROVIDER TRAINING

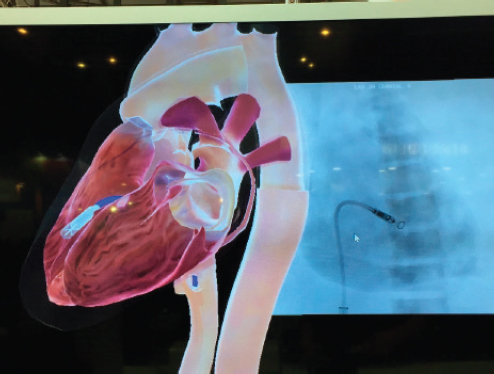

Walker presented to workshop participants about using technology to teach health professionals how to implant and program devices that Medtronic manufactures, such as implantable pacemakers. This type of

training is an adjunct to the training that providers receive in education and their fellowships. As the devices evolve over time, the providers have the opportunity to receive further training.

The motivation for developing this training, said Walker, came from several challenges that were identified. First, said Walker, moving into emerging global markets requires a different training model than what is used in the United States. Walker said that in the United States, there are around 1,600 technically trained Medtronic employees to support and educate providers. In countries like China and India, they have only a handful of people to support a large number of providers. Technology is the “only answer” to providing globally consistent quality training and support in these countries, she said. Another challenge, said Walker, is that professional education is largely voluntary, and professionals are incredibly busy. Finally, modern learners are visual, impatient, and social, said Walker. They want training opportunities that are fun, fast, and that can be accessed anytime and anywhere. With these challenges in mind, Medtronic sought to create training programs that were so engaging and fun that the program would grow by word of mouth.

Walker discussed two types of technology that Medtronic employs: augmented reality and interactive video. Virtual reality, said Walker, is an entirely digital representation of an object, the environment, or the world. Augmented reality, in comparison, adds a digital layer to the existing, real world. Medtronic worked with CAE Healthcare to come up with a training solution to offer simultaneous training to numerous learners using their Microsoft Hololens platform (CAE Healthcare, 2018). This augmented reality headset program offers a 3-D image so learners can see how and where to implant a small leadless pacemaker device through the groin. Surgical implanters in training use online modules to learn about the procedure, then can use the augmented reality simulator to “practice” implanting the pacemaker (see Figure 3-3). The simulator allows the provider to actually feel the heartbeat and feel the “tug” of the implanted device, said Walker. Cox asked Walker to explain how Medtronic assesses the competency of the providers that have been trained. Walker responded that Medtronic requires providers to have certain basic skills before being trained. She noted that because the industry is not responsible for credentialing, it is “up to the hospitals” to decide how and whether to allow the provider to perform the procedure. In response to a question from the audience, Walker noted that many procedures require a team approach, and that Medtronic seeks to train the entire team together.

The other technology that Medtronic uses, said Walker, is interactive video. She noted that people watch a lot of video—more than 1 billion users watch 1 billion hours of YouTube videos every day (YouTube, 2018).

SOURCE: Presented by Walker, November 16, 2017. With permission from Jay Reid.

However, video is usually a passive experience and not an ideal way to engage and teach learners. Interactive video engages viewers in the content by allowing them to choose the topics, drive the storyline, and decide how they want to learn. Walker pointed out that many Medtronic videos are interactive and require the viewer to be involved by making decisions, taking quizzes, and providing feedback. This type of active learning engages the learner in the educational process and improves retention.

Walker acknowledged that integrating high-tech tools into training is expensive; however, for Medtronic, it would be cost prohibitive to not use technology when doing trainings in both developed and emerging markets. Not only does the use of technology in training allow Medtronic to reach more people, but standardizing the curriculum on a global scale reduces inefficiencies and saves money in the long term, said Walker.

REFERENCES

BMJ. 2016. World will lack 18 million health workers by 2030 without adequate investment, warns UN. BMJ 354.

CAE (Canadian Aviation Electronics Ltd.) Healthcare. 2018. Limitless learning. https://caehealthcare.com/hololens (accessed March 7, 2018).

Medical Profession. 2018. Medical profession, wow I love it. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/Medicalprofession (accessed April 12, 2018).

Pimmer, C., and K. Tulenko. 2016. The convergence of mobile and social media: Affordances and constraints of mobile networked communication for health workers in low- and middle-income countries. Mobile Media & Communication 4(2):252–269.

Pimmer, C., S. Linxen, and U. Gröhbiel. 2012. Facebook as a learning tool? A case study on the appropriation of social network sites from mobile phones in developing countries. British Journal of Educational Technology 43(5):726–738.

Pimmer, C., F. Bruhlmann, T. D. Odetola, O. Dipeolu, U. Gröhbiel, and A. J. Ajuwon. 2018. Instant messaging and nursing students’ clinical learning experience. Nurse Education Today 64:119–124.

Poncelet, A., and D. Hirsh, eds. 2016. Longitudinal integrated clerkships: Principles, outcomes, practical tools, and future directions. North Syracuse, NY: Gegensatz Press.

YouTube. 2018. YouTube by the numbers. https://www.youtube.com/yt/about/press (accessed April 10, 2018).