CHAPTER 4

Barriers to Effective Communication Between Scientists and Stakeholders

There is a recognized gap between scientists and stakeholders in terms of the use of scientific information to influence decision making and to collaborate on the development of usable knowledge and understanding (Bartunek et al., 2001; Bartunek and Rynes, 2014). Here, “stakeholder” is broadly defined as any person or entity with an interest or stake in the issue at hand (EPA, 2017). Stakeholders can be members of the general public, a community, a company or industry, an organization, a government agency, or a practitioner such as a city planner or emergency manager. In the Gulf Coast, stakeholders live in the region and maintain and contribute to the state of the coast, making decisions on a range of issues from coastal restoration to adaptation planning. Moreover, they are likely to be influenced by adaptation planning and management decisions (Alexander, 2013). While this chapter touches on the perspectives of stakeholders in general (especially in the sections Scientist Perspective and Media and Communication), there is particular focus paid to “practitioner” stakeholders working on coastal issues related to resiliency and planning.

Clear and consistent communication between scientists and stakeholders (particularly at the federal, state, and local levels) is of paramount importance to project success (Byrnes and Berlinghoff, 2012). Despite the recognition that evidence-based decision making improves outcomes (Small and Xian, 2018) and that collaboration and coproduction of scientific information is beneficial to the process (Prokopy et al., 2017), effective communication1 often remains elusive. Task 3 of the committee’s Statement of Task (SOT) (see Box 1.1) was to “identify barriers to, and opportunities for, more effective communication among scientists and coastal stakeholders about improved monitoring, forecasting, mapping, and other data collection and research regarding long-term changes in U.S. coastlines.” The committee determined that this report would have greater value if it not only focused on

___________________

1 There are numerous models of efficient or effective communication. This chapter focuses on effective communication when information is conveyed with a shared meaning or a common language to achieve a goal (Grice, 1975; Granek et al., 2010; NASEM, 2017a).

the Gulf Coast, but also broadly addressed effective communication between scientists and stakeholders with regard to scientific knowledge and understanding, which encompasses the specific information mentioned in the SOT. This chapter identifies the barriers, while opportunities are addressed in Chapter 5. The following sections describe one proven model for effective communication (i.e., boundary organizations) and some barriers from the perspective of stakeholders and scientists.

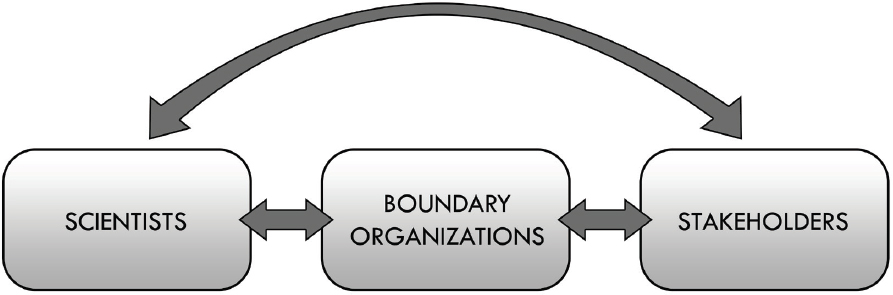

Over the past few decades a model for more effective communication has emerged, one that involves two-way flows of information among all those involved (Newstrom and Davis, 1986) and is sometimes mediated by a third party such as a boundary organization.2 In this chapter, boundary organizations are conceptualized broadly as playing an intermediary role between different disciplines and expertise, by facilitating relationships between information producers and users, and integrating user needs with the activities of information producers (Feldman and Ingram, 2009). Boundary organizations create and sustain meaningful links between knowledge producers and users, and are accountable to both. These organizations generally focus on user-driven science, seek to provide a neutral ground for discussion, and help deliver the resulting science to audiences who can use it. Some of the institutions that play the role of a boundary organization in the Gulf Coast include the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Sea Grant network (Sea Grant, 2018), nongovernmental organizations such as The Nature Conservancy (2018), and research institutions and consortia such as The Water Institute of the Gulf (2018) and the Consortium for Resilient Gulf Communities (2018).

Scientists and stakeholders sometimes play a more direct, engaged role in communication, whether they communicate among themselves or with the assistance of a boundary organization (Feldman and Ingram, 2009). Typically, a scientist or a stakeholder who is involved in the practice of communication plays the role of a “boundary spanner” (also called an “intermediary”)—an individual working at the edge of different groups who serves to connect those groups with each other. Boundary spanners engage in communication and outreach, whether professionally or more informally, that often serves to process information and represent the voice of outside stakeholders. Boundary spanners also work to engage stakeholders, negotiate relationships, and build connections among the different individuals or groups (e.g., scientists, stakeholders, boundary organizations) (Sandmann et al., 2014). For example, in the Gulf Coast, individuals in organizations such as the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and initiatives such as the Louisiana Coastal Master Plan have played the role of boundary spanner for a number of years.

___________________

2 The Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs (Guston et al., 2000) offers a well-recognized definition of boundary organizations: “Boundary organizations are institutions that straddle the shifting divide between politics and science. They draw their incentives from and produce outputs for principals in both domains, and they internalize the provision and ambiguous character of the distinctions between these domains. It is hypothesized that the presence of boundary organizations facilitates the transfer of usable knowledge between science and policy.”

Figure 4.1 shows an idealized representation of effective communication flow among scientists (those who generate data and improve system understanding, whether from the government, academia, or the private sector), boundary organizations (facilitators who serve as brokers, negotiators, and translators between scientists and practitioner stakeholders or the public), and practitioner stakeholders (e.g., city planners, emergency managers, coastal planners). It is important to note that scientists can also be stakeholders and that there may be some overlap among the three groups. Communication may occur across and among all three of these groups (and this is often most ideal), or the pathways may be two-way. For example, when communication occurs directly between scientists and stakeholders, scientists will tend to communicate the latest results that are usable and actionable by stakeholders, while stakeholders communicate their knowledge and understanding, which in turn informs and grounds scientific research.

STAKEHOLDER PERSPECTIVE

As has been mentioned in previous sections, the Gulf Coast is heavily influenced by the energy industry. As such, much of the population along the northern and central Gulf Coast is integrally linked with the energy industry’s successes and challenges (see Figure 4.2). This is especially relevant in the face of projected changes to the natural coastal system and underlying feedbacks with the industry infrastructure and operational activities. There is an awareness among the populace that the energy industry needs a highly skilled workforce (Theriot, 2014; Hochschild, 2016), and that the energy workforce is an integral part of a coupled natural-human system. Furthermore, there is an understanding that long-term

physical changes to the Gulf Coast influence both the local population and the energy industry, and that an increase in flood risks affects energy infrastructure, the people who work with that infrastructure, other people in the region, and the infrastructure that they use (LACPRA, 2017). This is a potential opportunity for effective communication.

However, the deep historical linkages and dependencies between the energy industry and surrounding communities can create challenges for effective communication, especially regarding research needed to understand long-term physical changes along the Gulf Coast. For example, several authors have noted that people in Louisiana are simultaneously grateful to the energy industry for providing well-paying jobs in a region that has not always had a strong economy, while also being critical of the energy industry’s role in wetland loss and environmental contamination (Theriot, 2014; Hochschild, 2016). Hochschild (2016) describes how these complex employment and social ties impact the flow of information among citizens, stakeholders, and decision makers at public forums in southern Louisiana.

It is within this sometimes contradictory backdrop that the committee discusses more effective communication between scientists and stakeholders. Insights reported here come primarily from in-person discussions at a committee workshop held in September 2017 and from information-gathering sessions during other committee meetings (see Chapter 1 and Appendix B for additional information). Insights presented here are drawn from those discussions and subsequent deliberation within the committee, supplemented by relevant scientific literature. The stakeholders who participated in the workshop and in meetings represent practitioners working on the frontlines of issues related to coastal resiliency and planning at the local and the regional level, including state and local agencies, the energy industry, organizations working with the public, and boundary organizations. These practitioner stakeholders are both producers and consumers of scientific information, as well as translators of that information to other stakeholders, including members of the general public. Stakeholders not present at the workshop but who may have a focused interest in coastal systems include those who fish for a living or for recreation, those who depend on or engage in tourism, and business owners in flood-prone areas, among others. These individuals are likely to be served by practitioner stakeholders and boundary organizations and may engage with scientific information through media. The majority of insights from the literature come from the Gulf Coast Climate Needs Assessment (Needham and Carter, 2012), conducted in 2012 by the Southern Climate Impacts Planning Program.

Five main barriers emerged from discussions with stakeholders in the region: resource constraints, limitations on the usefulness of scientific products to support decision making, factors contributing to communication success and failure, difficulties with communication among stakeholders, and challenges for boundary spanners and organizations. Each of these is discussed in further detail in the following section.

Resource Constraints

Four resource constraints—money, time, availability, and expertise—reportedly make the use of scientific information difficult in stakeholder decision making. Lack of financial resources or budgetary constraints can hinder access to information, especially when there is a fee associated with information access (Needham and Carter, 2012). Limited time is another constraint. Given the broad range of activities that practitioners engage in during their work day, it can be difficult to block out the time necessary to sort through available scientific research and interpret data for informed decision making. Even if time were not a constraint, it is difficult for stakeholders to know about all possible types and sources of available information that may be of use to them. In addition, the proprietary nature of some scientific information collected by the private sector (e.g., some data collected by the energy industry or others in the private sector) may prevent access. Lack of expertise may also hamper stakeholder ability to use scientific information to make informed decisions even if they have access. Some stakeholders may not be able to easily discern trustworthy or credible sources, and thus may be ill-equipped to judge the quality of scientific research.

Limitations on the Usefulness of Scientific Products to Support Decision Making

Relevance, timeliness, and usability of information are all central to the extent to which it can be used effectively for decision making. Stakeholders get their scientific information from a variety of federal, state, and local sources. In addition to these sources, stakeholders also draw from local knowledge and citizen science to inform their decisions with respect to resiliency and planning. Stakeholders felt that decision making in the Gulf Coast could be improved if stakeholders had more rigorous, comprehensive information that better characterizes and integrates the ecological, physical, and human components of the coupled natural-human system.

Practitioner stakeholders use scientific products (e.g., decision-support tools, simulations, datasets) to inform their decision making. Products tailored to specific user needs tend to be the most useful, applicable to, and used in stakeholder decision making (NRC, 2009; Dietz, 2013). These could be developed in conjunction with stakeholders or with stakeholder needs in mind from the beginning. Many products, however, are neither directly relevant to stakeholder needs nor vetted for quality and applicability. Many scientific products and tools are not accompanied by sufficient instructions or training on how to apply the provided information to the decision-making process, which means potentially useful information could go unused or be misused. Many stakeholders acknowledge they end up relying on products that are intuitive and easy to use, rather than potentially more sophisticated but complicated tools.

Practitioners also have to be careful that scientific information is not seen as serving the interests of one group over another, which could affect the extent to which stakeholders are willing to engage or use certain data. This was a particular point of focus for Louisiana when developing its Coastal Master Plan (LACPRA, 2017). To build trust in the plan’s results, the state appointed a number of scientific advisory panels to oversee and review scientific research during plan development, conducted regular public and stakeholder outreach to explain the science behind the plan, made resulting datasets available for public use, and ensured all relevant policy analyses, metadata, and quality control were well documented.

Factors Contributing to Communication Success and Failure

There are many modes of communication among scientists, practitioners, and the general public, ranging from preparing and sharing technical documents and convening outreach meetings to posting on social media and presenting educational displays in public spaces.

Workshop participants expressed the view that communication success can be measured in a number of ways, including whether projects are supported by the larger constituency, even though some conflicts among the parties may exist; whether there is consensus among diverse groups (or at least mutual understanding of others’ perspectives); whether conflict is reduced; and whether the public is able to discern among facts, assumptions, and values when making decisions. Some case studies related to communication success with Gulf Coast stakeholders are found in Box 4.1.

A lack of financial resources, the logistical complexity of communication between scientists and stakeholders, difficulty in identifying other relevant stakeholders, and lack of human resources contribute to communication failure. Stakeholders at the Houston committee workshop also reported, specifically, that some members of the public in the Gulf of Mexico do not understand or accept scientific consensus about climate change, which makes it difficult to talk about issues such as sea level rise (as also noted by Needham and Carter, 2012). There is a growing body of literature suggesting the extent to which science, especially politically polarizing topics such as climate change, provides barriers to effective communication. More research is needed to understand how to enhance evidence-based decision making (see, e.g., NASEM, 2017a). Moreover, regional differences between stakeholders and the general public can make it difficult to know how to best translate information for delivery to different groups.

Difficulties with Communication Among Stakeholders

Stakeholders engage regularly and well with local, state, and federal agencies; elected officials; nongovernmental organizations; the private sector (e.g., engineering firms, con-

sultants); and the public. Generally, interactions with academics (both within the Gulf Coast region and beyond it) were considered to be better when there was a two-way flow of information between scientists and stakeholders rather than a one-way flow from scientist to stakeholder or vice versa (e.g., Beierle, 2002; Kirchhoff et al., 2013). However, there is a need for greater interaction with industry and with vulnerable populations.

Based on workshop and information-gathering meeting discussions, there appears to be limited information sharing between stakeholders and some parts of the private sector (most notably, the energy industry, although other sectors mentioned included the insurance and reinsurance industries, finance sector, and the military) on topics such as industry assets, risk mitigation and communication, and emergency planning. Communication among stakeholders and industry is complicated for several reasons. First, the energy industry is not homogenous and represents many large, complex organizations, so it is not always clear to whom stakeholders should be directing their inquiries or how to develop a strategy for communication. Second, industry representatives may have reasons for not sharing data, including the desire to prevent their competitors from gaining an economic advantage,

financial disclosure laws or regulations, impacts of disclosures on financial markets, and the possibility of litigation.

Stakeholders often have difficulty reaching out to vulnerable populations, such as rural and indigenous communities, low-income communities, people who speak different languages, communities with low literacy levels, and disabled or elderly people. Box 4.2 discusses an approach taken by the State of Louisiana to address this issue.

Challenges for Boundary Spanners and Organizations

Boundary spanners and boundary organizations face three main challenges. The first challenge is obtaining approval or acceptance from local- or state-level officials and community members to participate in community engagement, which, if achieved, can help community leaders see the value of engaging with boundary spanners or boundary organizations. The second challenge is establishing true two-way flows of information between scientists and stakeholders, especially if participants on either side hold more parochial perspectives about their roles and the provision of scientific information. The last challenge

is that the process of communication necessitates the involvement and coordination of multiple entities and individuals, which can make progress slow or difficult.

SCIENTIST PERSPECTIVE

Despite growing recognition over the past few decades of a need for improved communication between scientists and stakeholders, such communication often remains limited to scientists (whether in academia, industry, or as a practitioner) who are either inclined to do so, have some level of job security (e.g., tenured faculty), or both (Jacobson et al., 2004). Four main barriers are discussed in the following section: institutional and interpersonal barriers, trust, “outsider” status, and underuse of science communication tools.

Institutional and Interpersonal Barriers

Weerts and Sandmann (2008) discuss factors that are barriers or facilitators to effective communication at institutions such as research universities. Institutional barriers arise for a variety of reasons, including leadership (e.g., chairs, deans, provosts, supervisors, senior colleagues) who may discourage a perspective that views community members as stakeholders or learning partners, and thus oppose community engagement. A personal barrier exists if a scientist does not see value in communication and mutual learning with stakeholders

Some scientists hold the view that stakeholders, especially members of the general public, do not act rationally (Ariely, 2009). Therefore, engaging with stakeholders is pointless because the presentation of scientific facts will be met with fear, dismissiveness, misunderstanding, or worse. Other research suggests that people do not in fact act irrationally (Fischhoff, 2013; Fischhoff and Scheufele, 2013); rather, they react to information in view of their unique circumstances, understandings, ideologies, and so on. Other scientists view communication activities, such as engaging with stakeholders, as a form of advocacy, which they do not see as their role in society (Lackey, 2007). Engaging the community may force scientists to either take a position that undermines their credibility and legitimacy or influences their ability to be objective, which could compromise their research.

Trust

Trust and confidence may also limit effective communication between scientists and stakeholders. Research in risk communication suggests that trust (comprising perceived competence, objectivity, fairness, consistency, and faith) and confidence (an enduring experience of trustworthiness over time) are necessary for effective communication (Renn and Levine, 1991). Both trust and confidence are necessary components when assigning

credibility to a source of information or an organization. Trust in media, industry, experts, government, and nongovernmental organizations is on the decline (Harrington, 2017). This lack of trust and confidence can make it very difficult for communication among scientists, boundary organizations, and stakeholders to be effective.

“Outsider” Status

Another factor that limits communication is that scientists from outside the Gulf Coast may be considered as “outsiders” by “insider” stakeholders. Research in social psychology and sociology suggests that relationships between ingroup and outgroup members tend to be marked by discrimination, whether that be favoritism toward insiders and an absence of favoritism toward outsiders or being dismissive of outsiders if they are seen as a threat or hindrance (Turner et al., 1987). This dynamic can make it very difficult, if not impossible, to engender trust among groups, let alone build effective communication. Indeed, this has been observed across a wide range of domains involving communication among stakeholders from management of natural resources (De Nooy, 2013) to decision making about energy development (Wong-Parodi et al., 2011).

Underuse of Science Communication Tools

The emerging field of science communication provides a broad set of tools for more effective communication between scientists and stakeholders (e.g., NASEM, 2017a), and more established fields of participatory action research, citizen science, and coproduction offer suggestions for how to establish better communication among interested groups (e.g., Whyte, 1991; Hassol, 2008; Bonney et al., 2009; Silvertown, 2009; Dilling and Lemos, 2011; Somerville and Hassol, 2011). The purpose of these tools is to facilitate lines of communication through which scientists can learn from stakeholders and stakeholders can learn from scientists. For example, participatory research was recently used to study the condition of infrastructure in Houston (Hendricks et al., 2018). Despite this richness, many scientists may not have the resources, tools, expertise, incentives to use, or awareness of the tools available to enhance effective communication, nor those frameworks for effectively developing those relationships that foster communication.

There is often an information gap between scientists and stakeholders, when each may hold expertise in their own domain areas and there is a need to share information. Some scientists believe that one way to bridge this information gap is through the provision of more information (Ben-Haim, 2001). Research suggests, however, that more information is not necessarily helpful; rather, providing the information that people need at the appropriate level is more effective (Bruine de Bruin and Bostrom, 2013; Fischhoff and Scheufeleb, 2013; Wong-Parodi et al., 2013).

Decision making under deep uncertainty (DMDU) methods are often used to support a participatory “deliberation with analysis” approach (NRC, 2009). This approach to decision analysis uses scenario analysis and interactive visualizations to facilitate conversations among decision makers, stakeholders, and residents. Critically, different viewpoints (e.g., assumptions about future conditions, preferences across different goals) can all be captured in the same analysis, allowing for an inclusive framework that seeks to highlight key tradeoffs, policy-relevant scenarios, and tipping points for deliberation rather than mask them through probabilistic assumptions or “black box” modeling choices.

MEDIA AND COMMUNICATION

Media formats play an important role in communicating issues regarding long-term coastal change to the public, decision makers, and stakeholders across the Gulf Coast. Some traditional news outlets (e.g., television, radio, print, and their online components) have dedicated coastal reporters, and as such, coastal issues are often in the news. There have been long format pieces (e.g., documentaries) about the region and the interactions between the landscape and the energy industry. The widespread presence of online weather and hydrographic data and models are readily being used by people to evaluate their own flood risks, as well as to enhance fishing trips and to ensure safety during recreational boating activities.

Both traditional and emerging formats can present barriers to communication. For example, some journalists may have a hard time evaluating key background information—which can be particularly problematic in the Gulf Coast given that some regions are educationally underserved. Additionally, the complexity of relationships (ecological, physical, and social) that exist across regions between the landscape and coastal development are often hard to summarize in many media formats that often require relatively short pieces. While digital and social media is becoming more common across the region, high poverty in some places can limit access to digital tools. For example, in 2015, 74 percent of U.S. households with an annual income less than $30,000 reported having access to the Internet, as opposed to 97 percent of households with an annual income greater than $75,000 (Perrin and Duggan, 2015).

Both traditional and emerging digital media formats present opportunities to communicate with the public, stakeholders, and decision makers. For traditional media, the presence of dedicated coastal reporters offers prospects for more communication. The cultural economy that exists across the Gulf Coast also offers opportunities to enhance communication concerning people and the landscape. Furthermore, social and other emerging digital media platforms offer chances for better communication and have proven useful particularly during environmental events and disasters.