6

Recruitment, Retention, and Collection of Data

This chapter summarizes the fifth session of the workshop on recruitment, retention, and collection of data with a focus on small or hard-to-reach populations, moderated by steering committee member Jan Probst (University of South Carolina). Vetta Sanders Thompson (Washington University in St. Louis) described issues and challenges associated with recruitment and retention for health research. F. Douglas Scutchfield (University of Kentucky) described the coalition building that has been done in Kentucky to improve rural health. Kathi Mooney (University of Utah) discussed technology for recruitment, retention, data collection, and intervention delivery. The invited discussant was Tracy L. Onega (Dartmouth College).

ISSUES AND CHALLENGES ASSOCIATED WITH RECRUITMENT AND RETENTION FOR HEALTH RESEARCH

Vetta Sanders Thompson said most recruitment issues are variations on themes. Researchers are more attuned to themes for some groups than for others. Traditional challenges to recruitment and retention include community attitudes toward research and the type of research being done, the institutions, and the universities. Sanders Thompson noted she and her colleagues did formative research to understand how members of the target community felt about medical research and their level of trust or mistrust in order to identify attitudes and other information about how individuals relate to institutions, researchers, providers, and health care strategies. The researchers found that not all institutions are perceived the same. In some

studies, the participants said they prefer some sense of government support and funding. In other instances, they put their faith in universities. Other times, they preferred the endorsement of health care providers.

She observed the term “research” is frequently used without thought about the type of research and people’s understanding of it. Researchers put very little time and effort into explaining their research, but the more people understand why the research is important, the more willing they will be to risk talking to researchers. Outreach strategies and community engagement are critical.

Sanders Thompson said that the basic requirements for success do not vary much by population. Flexibility is needed to adjust study recruitment to account for differences in location, behavior, media, technology use, and other factors. To meet communities and participants with openness and acceptance, she said, it is important to have the right staff, material, and approach. The right staff is essential in recruitment and retention. At the beginning of a study, researchers rarely think about the diversity of their teams. Staff who are reflective of a community will understand the community. She noted that people are attuned to these details. She said that if the staff cannot figure out how to navigate a particular environment, it may mean the researcher does not have the right staff.

Long-lasting partnerships are helpful. The challenge is to develop and maintain trust over time. To the extent possible, partnerships should be built before research is launched. Sanders Thompson said a basic requirement is to make the ask. She has found that researchers are reluctant to ask people, assuming that they will say no. In her experience people are more inclined to say yes, unless there are issues in the interaction that make them uncomfortable.

She observed that researchers need to know their audience and monitor deviations from expectations. Researchers need to go where people are, and different people are in different places. In addition to ensuring staff are from a variety of backgrounds, they must have people skills. They have to be adaptable and to put people at ease. Her experience has been that as long as participants believe the researcher is working with everyone and respects everyone, they are likely to work with the team. Team members need to understand how to engage with people in respectful ways. People will participate in research if they perceive it to be helpful to them, their family, or their community.

Sanders Thompson said elements of strategies like case management are helpful for recruitment and retention because they speak to commitment to the community. On her projects, people who recruit receive a lot of training. They are provided with up-to-date social service resource information that they can provide to potential participants. They are able to work with potential participants, help them make calls, and pro-

vide warm handoffs. In some ways, recruiters become embedded in the community.

Sanders Thompson said her project teams acknowledge birthdays and holidays. They have Facebook and Twitter pages that are not just about the research, but may have recipes, cartoons, and other features to keep people engaged. The projects have sponsored community events with political leaders, health providers, and others. Participants are invited but warned not to tell anyone that they are participating in a study. They are invited to just come in, bring the kids, and have fun.

Involving providers, political leaders, and church leaders signals that these groups support the research and see it as worthwhile. Sanders Thompson noted health care provider connections can be especially important. Researchers also need to use the right media for the market. In her projects, they pay attention to the radio stations, television stations, and newspapers that different groups prefer, and marketing dollars are divided accordingly.

The right incentives are important, and they may not be monetary. She said people like practical giveaways. For example, when her team was recruiting pregnant women, they handed out refillable cases of baby wipes. They use formative research to talk to people about incentives, show them the options, and solicit their opinions.

Education and research literacy are important, she said, and researchers need strategies to help people understand their work. The region of the country where the research will be conducted is important.

Immigration status matters as well, she said. On her projects, they work with people to make sure the resources for the community match the way the system responds to the community’s needs and its level of acculturation. They hire members from those communities for their staff. They do not rely on just having materials translated in advance. Gender, age, and generation are also important considerations. Older versus younger populations respond to different things and use technology differently.

She talked about the importance of detail and planning, down to the location of the office and ways to advertise the project. For one project in St. Louis, they chose office space next to the community college. It was neutral space where everyone felt comfortable. It was also beside a major highway, and they could make their logo and name large enough to have the equivalent of a billboard.

Project staff not only should mirror the community, but also receive extensive training. When working with pregnant women, for example, staff were trained on grief and support in case of a lost pregnancy, home visitation, and mental health support.

Sanders Thompson gave an example of a Neighborhood Voice Mobile Unit, a van customized for research. The van gave them some flexibility to

reach areas where interviewers might not want to go alone. Painted in bright colors with the study logo, the van held three interviewers who could interview participants in the van or in their homes. Some people did not want to allow researchers to come into their homes, while others felt more in control in their homes. Options are important. They chose zip codes with racial/ethnic, low-income residents and went to places where people congregate: health centers, laundromats, beauty salons, and barber shops. With a team of three in a van, it is possible to cover much more ground than if individuals are using systematic zip code–based recruitment. Another advantage was that people liked the van. It was easily visible. In areas where people felt unsafe, it was easy for the police who were watching for them to spot the van.

She noted that if a project requires call lists, researchers should make sure the list is effective. She has used call lists where the team exhausted the list and had to buy new ones. She has also used a list that was so effective they did not use a third of it. She suggested researchers interview the providers of call lists to understand their competence with diverse populations.

She related her experience in using the Internet. There are disparities in Internet use and limited literature on how best to address this divide. Formative research is important but needs to be evaluated. For example, during formative research in one study, African American men told researchers to contact them by text rather than email or telephone. Researchers tested this result, contacting them by all three methods. It was true that the men did not respond to calls, but they also did not respond to texts although they did respond to emails. She referred to earlier discussion (see Chapter 4) on the importance of piloting work and of evaluating what is learned.

She said one component of her experience has been as part of a partnership among Washington University in St. Louis researchers, community-based organizations, and community health workers serving the St. Louis Greater Metropolitan area. They have implemented a community-based participatory research training program for community members to promote the role of underserved populations in research, called the Community Research Fellows Training Program. The intention is to train community members to become good consumers of research, understand how to use research as a tool in improving health outcomes, and increase community members’ understanding of how to work with academic researchers. To date, 125 people have been trained in a 15-week program. They provide feedback to researchers in developing their programs, enhancing the likelihood the community will participate with their work.

IMPROVING HEALTH RESEARCH IN RURAL AREAS

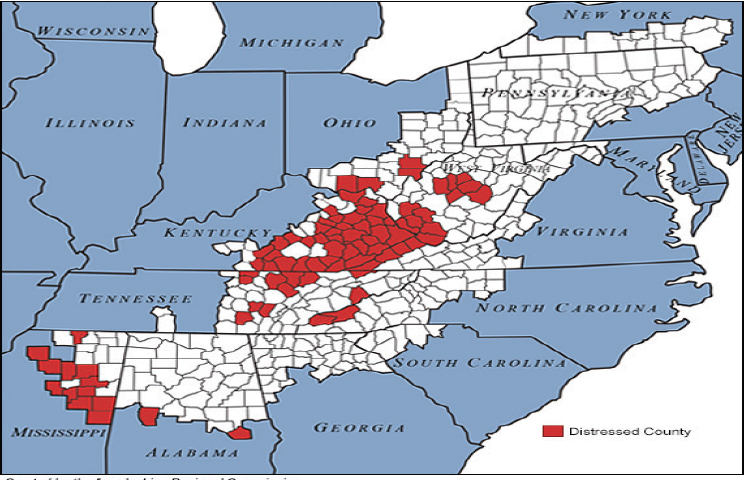

F. Douglas Scutchfield discussed health research in rural areas, focusing on the Appalachia area of Kentucky. Appalachia extends from New York

NOTE: Red areas are those in economic distress, as designated by the Appalachian Regional Commission.

SOURCE: Appalachian Regional Commission, https://www.arc.gov/program_areas/mapofarcdesignateddistressedcountiesfiscalyear2018.asp [June 2018].

to northern Alabama and Mississippi (see Figure 6-1). There are many distressed counties in Central Highlands Appalachia, which includes West Virginia, eastern Kentucky, and part of eastern Tennessee. The distressed counties are some of the poorest in the United States and have some of the worst health rankings. A substantial portion of illness in Kentucky is in the distressed counties.

Scutchfield then talked about the community-engaged research effort that has been underway in Kentucky for some time. It is a collaborative process between the research community, primarily the University of Kentucky, and community partners designed to benefit the community and advance knowledge. It identifies the assets in and concerns of communities and incorporates them in the design and conduct of the research. Formative research at the beginning helps to identify community assets in local institutions and resources, community associations, and individual people, especially local leaders.

He noted that community-engaged research moves along a spectrum with increasing involvement, from outreach, to consult, to involve, to col-

laborate, and, finally, to shared leadership. (See also Korngiebel’s description of community-based participatory research in Chapter 5.) He noted that the further along the spectrum a collaboration falls, the more likely it is to succeed.

At the University of Kentucky (UK), he has tried to identify within the College of Public Health all research projects in PubMed that have to do with Appalachia Kentucky, making summaries available to people who could use them. Dissemination of research findings and implementation are important parts of giving feedback to a participating community. It is important to inform the community about the results of the research and its potential applications.

Scutchfield described some of UK’s outreach activities, focusing on several communities and the partnerships created. Many activities initiated by UK rely on outreach and relationships with patients and populations in terms of research, service, and education. He noted the Centers for Excellence in Rural Health in Hazard, funded by the Commonwealth of Kentucky through UK to educate and work in the communities of Appalachia, and the Appalachian Translational Research Network, an extensive liaison of universities and academic medical centers in Appalachia that is funded by NIH Clinical and Translational Science Awards to work collaboratively on research translation. Study coordinators in Hazard and Morehead are from the community and help with recruitment and retention for UK research programs. The Markey Cancer Center, another example of UK outreach, is a success story in the state. Another partnership, called the Health Education through Extension Leadership program, exists among the UK College of Agriculture Cooperative Extension Service, UK College of Medicine, and UK College of Public Health. The extension agents are trusted members of communities, who also serve as ambassadors to UK, disseminating information and working on projects within the community. He described community-based research networks in public health, dentistry, and rehabilitation.

His first suggestion about how to be strategic in approaching communities for research opportunities was to encourage the accreditation of local health departments through the Public Health Accreditation Board, a nonprofit, nongovernmental organization. To become accredited, local health departments must participate in or lead a community health assessment program (CHA) and submit a community health improvement plan (CHIP). Another recent change is a result of the Affordable Care Act. It requires every not-for-profit hospital to conduct a CHA and address how the hospital plans to provide community benefits to address the identified needs. In many cases the hospital(s) collaborates with the health department in doing a CHA/CHIP. The assessments are a tremendous opportunity for researchers to collaborate with health departments, hospitals, or consortia.

For example, the opioid problems in Appalachia almost always make the priority list of departments or hospitals that have done a CHA and CHIP, so they are looking for collaboration and expertise. UK has taken advantage of these opportunities for collaboration. Scutchfield said that Kentucky has embraced the notion of public health accreditation and now has a substantial portion of the state covered by accredited health departments. He observed, however, that the areas with the worst health status are least likely to pursue accreditation.

One of the studies he has worked on with collaborators from UK was entitled Models of Collaboration Involving Hospitals, Public Health Departments, and Others: Improving Community Health through Successful Partnerships.1 The purpose was to identify models of collaboration in improving community health that are operational and successful. As an example of collaboration in cancer control and treatment, he cited the Markey Cancer Center. The Kentucky Cancer Consortium, created by Markey and funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, focuses on multiregional and state-level efforts in cancer control. The Kentucky Cancer Program (KCP) is a state-funded, university-affiliated and community-based regional cancer control program, working at the regional and local levels. KCP works through a network of 13 regional offices staffed by cancer control specialists who lead in cancer prevention and activities for all 120 counties. KCP works closely with 15 District Cancer Councils to analyze local cancer data, identify and prioritize the community’s cancer needs, and develop interventions/solutions. KCP is jointly administered by the UK Lucile Parker Markey Cancer Center and the University of Louisville James Graham Brown Cancer Center. This network of district and community centers provides a valuable potential partnership for researchers interested in cancer prevention and community-engaged research.

As a result of these collaborations, from 1999 through 2014, the screening rate for colorectal cancer increased from almost 35 percent to almost 70 percent, and there was an age-adjusted decrease in the incidence rate of colorectal cancer from almost 69 percent to almost 53 percent.

Scutchfield identified several keys to success. At the top was a focus on dissemination and implementation science (see Chapter 5)—with extensive formative research, training, resources, funding, and technical assistance. He said sustainability and coordination of activities and players are critical. In Kentucky, researchers can capitalize on community-clinic partnerships that are already in place in parts of Appalachia Kentucky.

___________________

1 See http://www.uky.edu/publichealth/studyOverview.php [March 2018].

USING TECHNOLOGY FOR RECRUITMENT, RETENTION, DATA COLLECTION, AND INTERVENTION DELIVERY

Kathi Mooney described the use of technology in the areas of recruitment, retention, data collection, and intervention delivery. She suggested using technology if it contributes to the purpose of the study or the methods being used. Some exciting developments in technology have the potential to overcome some research challenges.

Mooney said Utah has health issues related to its geographic space and low-density population. Everything outside the Salt Lake City Metropolitan Area is vast mountain and desert, with 96 percent of Utah’s land mass classified as rural areas (fewer than 100 people per square mile) and 70 percent as frontier (fewer than 7 people per square mile). In addition, the Huntsman Cancer Center addresses the needs of people in five surrounding states. This catchment area makes up about 17 percent of the land mass of the United States. To conduct research on the population of the catchment area, researchers have to figure out how to extend interventions outside the walls of the cancer center.

Recruitment

Mooney referred to Sanders Thompson’s framing of recruitment and the importance of trust, marketing, and engaging the population. These issues are also relevant in choosing to use technology or to use a combination of methods. For example, there are several ways to use social media, many illustrated by Sanders Thompson, such as a media site, Facebook advertising, or a Twitter account. From the respondent-driven sampling point of view, she said, once seeds have been recruited, they may recruit others by tweeting or putting something on their Facebook pages. Researchers should think about how social media might help.

She described the Apple-Stanford Heart Study that started in December 2017 with a lot of social media attention. It is a partnership between Apple and Stanford University to test the Apple Watch to see whether it can detect heart irregularities, particularly atrial fibrillation. One of the points of this example, she said, is that Apple, Amazon, and others are looking at health technology and health products. The research community needs to be moving forward in use of technology too, because if not, it will be left behind in developing and using health technology.

Her second example was using the Army of Women Susan Love Foundation for recruitment. Her organization had developed a small app to help women prepare for clinic visits and prioritize topics for discussion with their provider, particularly concerning symptoms. It wanted a quick pilot test and used the Army of Women, women who are willing to be

recruited to studies. The Army of Women sends invitations to their members in email blasts until the desired number of people have volunteered. Her study was interested in 100 women for the pilot, but received 1,000 responses in the first 4 hours. She noted several challenges with this type of approach. First, in her case they had not given out distinct numbers, and some individuals participated multiple times to increase the incentives they received. Second, researchers should consider whether participants can accurately provide the information needed. Third, can researchers count on a representative group if they are going only to women who have volunteered to participate in breast cancer research on a social media site? Researchers will know whether the app works with this group, but will results be generalizable.

Mooney referred to the discussion on electronic health records (EHRs; see Chapter 3), some of which have patient-facing portals. She noted that there may be institutional review board issues associated with using EHRs to generate potential participants to a study. She suggested some thought to further EHR development by allowing people to give prior consent to being contacted for participation in studies for which they might be eligible.

Video advertisements or opportunities inviting people to participate in a study may also be a worthwhile way to supplement recruitment efforts. Videos can be posted on websites or sent to other people. Videos may also be a way to address literacy issues.

Mooney said the University of Utah Huntsman Cancer Institute participates in ORIEN, a research collaboration among a number of cancer centers in a program called Total Cancer Care. She said that there needs to be a human touch to the recruitment, but a video can explain the details of what the consent involves. She said that they will be moving to a video-based consent process. This combination of approaches makes the process very efficient.

Retention

Technology can also help with retention in an efficient way, such as through automated reminders, encouragement from influential stakeholders, or websites. Mooney provided an example from her studies. They have recorded multiple audio “thank-you” type messages from participating physicians and nurses. At the end of every telephone interaction with a patient providing automated data, they played one of these recordings. Patients heard the voices of their providers linking it back to their care and also reinforcing the study.

One of the issues with updates, boosters, and newsletters is to know how much is enough and how much is too much for a given community. She recounted that in one study, if a participant had not called in at the

designated time, the system called them. Some participants objected to the reminders. It is important to have flexibility with automatic reminders.

Mooney noted that research management platforms can help track participant accrual and retention. She uses REDCap, a research platform developed at Vanderbilt University. Besides data capture entry with HIPAA-compliant standards, they have programmed the platform to provide weekly reports about how many people were approached, how many people were accrued, and whether there were dropouts and the reasons. Information is organized by accrual site as well as by race and ethnicity so they can track progress and easily spot issues that need addressing. This information is invaluable for monitoring whether segments of the population are missing and whether corrections to the process are needed. This use of technology helps to monitor the progress of the study, allowing for timely correction.

Data Collection

Mooney stated that data collection or electronic capture of patient-reported data can make research more dynamic, and this is particularly important for examining behavior changes. Instead of collecting information at regular intervals, a continuous flow of information is received. This results in many data points per person, and may mean that a small sample is acceptable. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) and electronic-activated recorders sample in real time when people are doing real-world activities. These approaches result in a lot of rich data. In addition, electronic collection of patient-reported questionnaires, particularly with questionnaires that permit computer adaptive testing, decreases respondent burden and errors of data entry.

Mooney talked about the burgeoning area of wearables, home sensors, community sensor data, and GPS data. This new area is advancing what can be done in collecting data and in machine learning to understand it. Telecommunication is another way of interacting with people remotely through telehealth and Skype. For example, she said, one of her colleagues did a study on heart rate variability with lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender couples who did not want to come to the university to participate in interviews. Researchers sent them equipment with instructions on how to wear it. Interviews were conducted via Skype at the participants’ convenience. With this approach, they had a robust response from the community because they adapted the intervention and data collection to fit the community.

Intervention Delivery

Multiple platforms can be used for intervention delivery. Using automated systems has one huge advantage because it guarantees fidelity in how the intervention is delivered. This also simplifies replication in other places.

Mooney said that she is involved in multisite studies and now has one at Grady Hospital in Atlanta and at Huntsman Cancer Institute in Salt Lake City. She knows the intervention delivery is identical, because the automated woman talks the same way every time in the same voice and for the same length of time. This also simplifies training the people involved in face-to-face contact. In addition, it is easily adapted to different languages or dialects. The technology makes things scalable. She observed implementation science is key, because usually the challenge is in getting providers to adopt interventions that work.

Mooney talked about the value of adaptive intervention designs, reminding the audience of sequential multiple assignment trial designs (see Chapter 5). She described an alternative, the Just-in-Time Adaptive Intervention, that allows researchers to use technology to provide appropriate interventions at the time the individual needs it as the situation for the person changes. This allows for personalized precision care. These might be delivered by EMA or other approaches. She provided an example from her research in coaching family caregivers, who may deal with changing stress levels throughout the day in response to their family member’s illness. This approach allows researchers to be dynamic in their interventions. For example, if the person has a wearable device, the researcher can sense heart rate variability and use that information to decide when an intervention might decrease the person’s stress and vulnerability versus when a positive intervention might be well received.

Concluding Example

Mooney described Symptom Care at Home, a remote symptom monitoring and automated self-management coaching platform with an alert component that alerts providers of patients’ symptoms that are poorly controlled. It was developed to help people in their homes after they had come to Huntsman Cancer Institute, had chemotherapy, went home, and over the next 3 weeks felt poorly. Researchers wanted to make sure that when the patients’ symptoms were out of control, there was an efficient way to improve outcomes to avoid suffering and emergency room visits.

They make use of a telephone-based, automated voice response system (IVR). The basic platform has served them for 15 years. They are now adding both web and app features but will keep the IVR. The challenge

will come, she said, in testing to make sure they can use all of the features and have people use the one they prefer at the time they need the system.

The system has three components: daily monitoring of symptoms, immediate automated coaching on the phone about the person’s reported symptoms and their severity, and alerting providers. An evaluation of system use in two settings, chemotherapy and end of life, showed significant benefit for patients in both situations. For chemotherapy researchers found that patients had significantly less symptom severity than with usual care, and the benefit extended across geography and race. In the hospice study, patients had significantly less symptom severity than with usual care, and there was a more rapid onset of patient benefit. They also found a reduction in the amount of daily moderate to severe distress for family caregivers, including levels of fatigue, poor sleep, and anxiety, suggesting that the system helped to maintain caregiver vitality.

Mooney observed that one of the most striking findings was the system’s benefit for men. She noted that for some people anonymity in reporting symptoms is very important for success. She suggested that men’s mental health is aided by their ability to anonymously report anxiety and depression and receive automated coaching and intervention as needed.

Mooney concluded that in her experience, technology has been successfully used across the research phases. Health technology is a growth industry, and health researchers should look for equivalent advances in use of technology in health research. She noted that researchers should always engage participants in learning how to improve the use of technology. Mooney stressed technology is the vehicle, but the content still needs to be of high quality. If technology did not work in a study, it may have been that the content was not good: the retention messages, the recruitment messages, or the intervention content. It is the combination of the content and the vehicle that is important. She closed by suggesting further research is needed concerning best practice in the use of technology in research methods.

INVITED DISCUSSANT

Tracy Onega noted small populations, hard-to-reach populations, and populations that are both small and hard to reach are highly diverse and may be quite distinct. Each will require time and effort to identify the appropriate approaches to recruitment, retention, and data collection. Improving health research for these groups involves two tasks: (1) to identify commonalities that can help move research forward with common approaches and (2) to find the distinctions that need to be recognized so that populations can be approached in unique ways.

In terms of commonalities, she said both personal-touch and remote-reach approaches are important, and the appropriate mixture seems to

vary incredibly across populations, research goals, geography, and other factors. The commonality is that a mixture is needed; the distinction is in the relative proportion of the two. Other commonalities include an increasing reliance on technology, as Sanders Thompson and Mooney described, and the need to know and understand the target population. For all of the research on recruitment and retention in small and hard-to-reach populations, success is predicated on knowledge of the population. Another commonality is that data collection and measurement objectives are inherent as part of research. A final commonality is that all research proceeds across phases: identifying what the population needs, identifying the target population based on an identified need, and determining what recruitment strategies are appropriate, as well as retention strategies, implementation, and sustainability.

Onega described distinctions that may require unique approaches. They include settings—rural versus urban, specific versus distributed venues, perhaps virtual or Internet based without a distinct location or locale. There are distinctions in sampling frames, whether of individuals, providers, or communities, or even whether a sampling frame exists at all. Sampling strategies and sampling units are distinct for different populations. The mixture of technology and the human component depends on characteristics of the target population, the geography, and the purpose of the research. Barriers may include linguistic, cultural, technological, geographic, and other challenges. Heterogeneous criteria are relevant for small or hard-to-reach populations. How are these populations defined, and how does that affect research activities?

Onega observed that the research process is typically thought of as occurring in a linear fashion, which she finds overly simplistic, as illustrated by Sanders Thompson and Mooney. Instead, data collection is infused across the spectrum of activities. Upstream, in the identification and recruitment phase, data collection helps inform and improve methods. In unique communities and small populations, some data collection is “implementation data” for the research process itself. Downstream data collection is vital to inform the outcomes and understand effectiveness for health and health outcomes across these populations. The infusion of data collection throughout the research supports adaptation and evaluation that are critical to success in working with small and hard-to-reach populations.

Onega highlighted innovative strategies from the three presenters. She pointed to Sanders Thompson’s description of the Community Research Fellows Training Program and her advice that having research teams “mirror the community” is critical to success. She lauded Scutchfield’s example of coalition building in Kentucky. She also observed that Mooney’s work and research demonstrated the innovative strategies that are coming about with technology-based approaches, social media, EHRs, integration of the

data and symptomology, wearable devices, remote sensors, video, and telecommunications. In some cases these technologies created new opportunities for the research, and in others they were additive to ongoing research.

Themes

One theme Onega gleaned from the presentations was the balance of technology and touch. She thinks this issue deserves thought as well as empirical and qualitative evidence. Data collection provides an empirical basis for what works, as Mooney’s presentation illustrated.

A second theme, she observed, is incorporating data collection across research phases. She said this seems like a critical element for understanding research in small populations, but it is not necessarily easy. There is burden on the population, the participants, and the researchers, in addition to extra cost.

Onega suggested that another theme is having models of research that work across scales. She said that Scutchfield’s examples illustrated a hub- and-spoke model that provides a very broad base with a network that can provide a foundation and framework to encourage and support community building, education, assessment, and research.

A theme she drew from Sanders Thompson’s presentation was the importance of knowing, understanding, and communicating with the target population. She also noted that though she agrees that “going where they are” and “mirroring the audience” are critical, these things may not always be possible. The more a researcher knows, the more he or she can target and appropriately tailor research objectives to the population. At the same time, data may identify a need for a population for which the researcher does not have in-depth knowledge. This suggests, she said, an iterative and probably cyclical but sequential process of identifying a need, knowing the target population, and being able to use that knowledge to adapt the research approach to be most effective and appropriate.

OPEN DISCUSSION

Ellen Cromley asked Mooney about challenges related to the adequacy of Internet technology, as well as protecting privacy and confidentiality in the digital environment. Mooney said that her team has not had difficulty because their current telephone platform allows for any type of phone. Internet service is not required for them to capture data. The system has alerts to the providers if there are poorly controlled symptoms, as well as built-in redundancies.

Scutchfield told a related story regarding the problem with broadband communication and Appalachia. He said that a Toyota plant had located

in Georgetown, Kentucky, a tremendous economic asset to the Commonwealth of Kentucky. A busload of Japanese CEOs of supply chain organizations that were feeding the Toyota plant was taken to eastern Kentucky, hoping the CEOs might have interest in setting up a plant there. As they entered the foothills of Appalachia, the CEOs lost their cell phone service. There was a mutiny, and the bus was told to turn around. The CEOs did not want to start a business in a place without cell coverage. Scutchfield said that last year the commonwealth decided to install broadband in Appalachia Kentucky. He and his research colleagues hope to take advantage of this.

Gordon Willis said he agreed with Sanders Thompson about having a diverse research team, but noted especially in the very early phases of research, it may not be feasible. He asked how to proceed, drawing from his experience in a study at a Baltimore health clinic. He suggested that frequently the problem researchers have in interacting with diverse populations is that their approaches demonstrate arrogance.

Sanders Thompson observed many researchers do not pick up on the cue that they need to be more humble and open to hearing that they need some help. She also noted that when people say “we can’t put together a diverse team,” they may be overlooking the diversity around them. She said people are looking for a signal of potential openness and a researcher’s willingness to share what he or she knows, just as they are sharing what they know. She said that she wants teams to be diverse to strengthen the pipeline. Hiring people from the community makes the community better off. She believes that researchers using their dollars effectively is one way to help make this happen.

Eugene Lengerich (Pennsylvania State University) observed that nationally, 80 percent of studies never reach their recruitment goal within the time frame or budget proposed. He observed that this is not just a small population problem, but applies to all studies. He asked how institutions can help to relieve this. Scutchfield said it has to do with the nature of the institution and its leadership. He said that the president of UK describes the institution as the University for Kentucky, with a mission to help people with their problems. He noted that if research efforts do not have that kind of leadership, it is more difficult to engage the community. Sanders Thompson said the Community Research Fellows Training Program could not have succeeded without leadership support. The leadership of the Siteman Cancer Center has made a commitment to be out in the community. She said the underlying theme is that leadership has to be supportive of community approaches and understand their value.

Mandi Pratt-Chapman (George Washington University) asked Sanders Thompson about resourcing the fellows program and the Patient Research Advisory Board. Sanders Thompson replied they are institutionally sup-

ported and have small amounts of foundation support. The faculty who do the training volunteer their time. Most work with other organizations and are committed to improving health outcomes in communities. The institution provides all the materials for the participants. Training is usually done in the evening. The institution provides food and transportation costs. Some trainees come back to assist with the next cohort. They are eager, she said, and her team cannot come up with enough opportunities for them. She said that sometimes if they are working with other groups and agencies, there are small amounts of compensation.

Jessica Xavier (Ryan White HIV/AIDS program, Health Resources and Services Administration) shared her experience as a transgender health care research worker working in mostly minority populations in and outside of the HIV epidemic. First, she said, the perfect cannot be the enemy of the pretty good. Data collection methodologies and systems evolve over time. They are dynamic, not static, and researchers should be open to new ideas, especially when working in programs that might be resistant to incorporating new cutting-edge technologies. Second, disaggregation reveals many health care disparities. It is important to disaggregate among the L, G, B, and T populations, all of whom experience different health disparities at different degrees due to stigma and other psychosocial reasons. Third, in her view, the failure to identify and respond to health disparities among small populations perpetuates health disparities. Fourth, researchers should always be mindful of Paul Brodeur’s very poignant saying, “The statistics are human beings with the tears wiped away.”

Diane Korngiebel appreciated the use of commercially produced health technology interventions, but raised ethical challenges. For example, she said, wearable technology has an end user license agreement with a “we are not responsible” or “you must agree to arbitration” clause. She observed this is very different from a research context where human subjects have protections that they do not give up. Second, the Apple Watch and Fitbit collect a lot more data than just one element. In industry, the privacy and data standards are different than in research. Researchers should be mindful of these things moving forward.

Mooney replied that these are excellent points about what is disclosed and what participants agree to. Disclosure and consent are important and could affect recruitment. Graham Colditz pointed to the new NIH guidelines for NCI-designated cancer centers that direct researchers to be doing research responsive to their catchments. He questioned how to balance a small population focus against the peer review and cancer centers’ acknowledgment that research must be responsive to a cancer center catchment population.