4

Trends in Workforce Development

Understanding important trends shaping the U.S. and global workforce can help the Intelligence Community (IC) prepare, adapt, and thrive as the landscape changes. Presenters in this session addressed the benefits of diversity on teams, trends in automation and artificial intelligence (AI) and automation and their impacts on the global workforce, and the role of AI as a partner with human analysts. Gerald (Jay) Goodwin, U.S. Army Research Institute for Behavioral and Social Sciences, moderated the presentations and discussions, and Noshir Contractor, Northwestern University, chair of the workshop steering committee, offered final remarks on the day.

THE BENEFITS OF DIVERSE TEAMS

“The IC’s success depends on its ability to predict, evaluate, solve, act, create, and verify,” stated Scott Page, University of Michigan. Diversity—especially in how people think—plays a role in each of these functions, he said, but the way in which it matters differs across these functions. He asserted that the cognitive diversity that comes from bringing people with different perspectives together leads to better analysis of problems.

Page drew some distinctions between this view of the benefits of diversity and common views on the subject. Traditionally, he observed, people have focused on “identity” diversity, with inclusiveness being valued only because it is the right thing, a societal good. Others, he explained, have mistakenly viewed team diversity as akin to diversifying an investment portfolio, where the benefit comes from spreading risk, with the outcome of achieving the average return between stocks that do well and those that

perform poorly over a period of time. Yet according to Page, research indicates that diversity is more than a societal good and that diverse teams outperform the average.

To illustrate this point, Page offered an example described in The Wisdom of Crowds.1 At the 1906 West of England Fat Stock and Poultry exhibition, 787 people provided their estimate of the weight of a steer. The average guess of this group was within 1 pound of the steer’s actual weight. This effect can be expressed in terms of the diversity prediction theorem, explained Page, saying, “We might think the crowd’s error is kind of the average error of the people in it. But if you actually do the algebra, it is not true. The crowd is always smarter than the average person in it, and the amount by which it is smarter depends on the diversity.” He explained that this is because the errors of different people tend to cancel each other out (i.e., one person’s prediction may be too high and another’s too low). As a result, he said, diversity provides groups with a bonus (better ability to make predictions) rather than providing an average, as would be suggested by the “spreading risk” analogy.

Page has examined a number of examples that illustrate how significant this diversity bonus can be if the group is knowledgeable. He noted that diversity of perspectives among crowds with little to no knowledge does not lead to better prediction. He cited research that examined the economic predictions of 28,000 professional economists over a 40-year period and found that the combined crowd prediction of these economists was 21 percent better than the prediction of the average economist.2 Moreover, he observed, improving prediction does not require such large “crowd” numbers, noting that the predictions of two average economists are 9 percent better than those of one economist, adding that even the best economist (10 percent better than the average economist) and the second-best economist result in just an 18 percent improvement in prediction over the average economist. “The reason this bonus is so big,” he said, “is because economists all disagree. . . . In a portfolio, you get average. A group of predictors, you get better than the average.”

Diversity also leads to improved problem solving, Page continued, with moderately large teams of randomly selected “smart” people outperforming teams comprising the “best” problem solvers, as demonstrated through repeated algorithmic simulations. He noted that other researchers have attempted to disprove this finding, creating teams of the best algorithms to compete against teams of diverse algorithms. However, he reported, multiple studies have confirmed that the team of diverse, less able algorithms

___________________

1 Surowiecki, J. (2005). The Wisdom of Crowds. New York: Anchor Books.

2 Mannes, A.E., Soll, J.B., and Larrick, R.P. (2014). The wisdom of select crowds. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 107(2), 276–299. doi: 10.1037/a0036677.

outperforms the team of variants of the best algorithm, and that for many problems, there is no test that can be applied to select the “best” team. As Page explained, “If you get two algorithms that are very different voting on the same move, it is really likely that it is a good move because the odds of making the same idiosyncratic mistake are really low.”

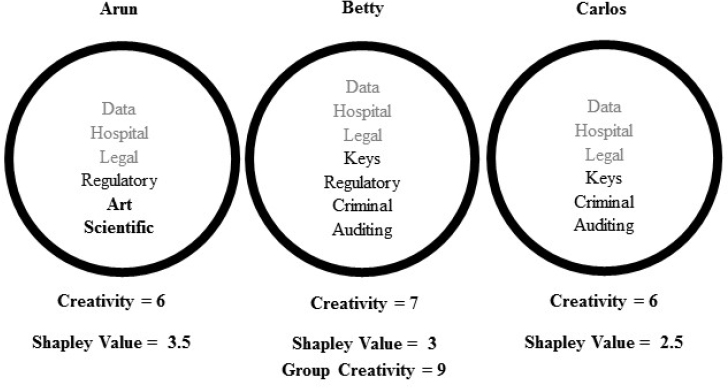

Page then presented Figure 4-1, which illustrates how diverse groups can be more creative than individuals. All three individuals in the group depicted in the figure provided their ideas for uses of blockchaining beyond cryptocurrency. Each was assigned a creativity score for the number of ideas generated and a Shapely value for each unique idea provided. The figure shows that even though Arun did not have the highest creativity score, he had the highest Shapely value because his ideas were different from those of the other members of the group. Page added that this approach can also become more sophisticated as ideas are weighted for their quality.

Page also explained that diversity related to identity (e.g., gender, ethnicity, age, sexual orientation) affects how people think, and this in turn leads to better outcomes. Each person, he said, is a “bundle” of different identities that interact in interdependent ways, and these elements cannot be disaggregated. In other words, the perspectives of an African American woman and a white man cannot yield the perspectives of an African American man.

SOURCE: Page, S.E. (in press). The Model Thinker. New York: Basic Books.

Page has begun to conceptualize diversity through collections of people’s different models. People can use models for many purposes, he explained, including to make logic visible, explain data, design, communicate, inform actions, predict, and explore concepts. He illustrated this point by describing technological and social influence effects within economic models that can explain aspects of income inequality. Assuming that inequality refers to upper and lower socioeconomic groups, he elaborated, sociological models point to poverty traps (e.g., groups of lower socioeconomic status live in neighborhoods with bad schools and few opportunities),3 assortive mating (marrying later in life allows insight into the educational background and potential income of one’s mate), and parental investment (in the form of tacit skills) as explanations for this gap. “If I want to talk about a policy intervention, if I want to act, if I want to design an institution,” he said, “all these models have to be in the room; otherwise, I am likely to make a mistake.” To avoid such mistakes, he stressed that it is necessary to avoid “the siren call of sameness.” This means, he said, that instead of choosing team members based on training similar to one’s own, one should select new team members based on the tools they add to the team. He noted that efforts to make these changes can also be reinforced through organizational structures and incentives.

TRENDS IN ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE AND AUTOMATION AND THEIR IMPACTS ON THE WORKFORCE

Andrew Ysursa, Salesforce, Inc., discussed trends in AI and automation and presented his views on their impacts on the workforce. He pointed to numerous headlines and warnings about the threats posed by AI and automation to jobs, adding that others speculate about the pace of the development of AI and when it might match or overtake human intelligence. He reported that results of a 2016 survey of 352 machine learning researchers predicted that AI had a 50 percent chance of outperforming humans on all tasks and for less cost in 45 years.4 In Ysursa’s view, with this lead time in mind, developers should focus on controlled, safe deployments emphasizing transparency, openness, and utility. He noted that several university centers

___________________

3 Bowles, S., Durlauf, S.N., and Hoff, K. (2006). Poverty Traps. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

4 Grace, K., Salvatier, J., Dafoe, A., Zhang, B., and Evans, O. (2017). When Will AI Exceed Human Performance? Evidence from AI Experts. Available: https://www.fhi.ox.ac.uk/will-ai-exceed-human-performance-evidence-ai-experts [March 2018].

and other consortia,5 comprising such companies as Salesforce, Google, and Facebook, as well as universities, have formed to provide a forum for discussing and addressing the ethical and societal challenges that AI may pose.

Ysursa acknowledged that other technological revolutions have occurred throughout history, but pointed out that in the past, technological change has shifted rather than diminished jobs. To illustrate this point, he noted that when the automated teller machine (ATM) emerged in the late 1960s and became popularized in the 1970s and 1980s, many thought bank tellers would lose their jobs; instead, however, the technology changed the nature of their jobs to focus on customer relationships. Ultimately, Ysursa observed, ATMs brought about more and smaller banks closer to where customers lived, requiring more rather than fewer tellers.

The U.S. economy has shifted in other ways, Ysursa continued. Since 1900, he elaborated, the economy has shifted from being primarily agricultural to industrial to service. But he argued that this “4th wave” of automation differs in important ways from these previous shifts as a result of the convergence of several forces accelerating the pace of change. Innovations and technological advances, such as the personal computer, the Internet, mobile technology, the cloud, the Internet of Things,6 big data, AI/machine learning, and automation, are transforming everyday lives, he said. He noted that the power of computing doubles every 18 to 24 months, and the resulting growth in the amount of data available provides the fuel for machine learning and AI. The more data available to provide training for algorithms, he added, the more insights can be gained.

Yusursa went on to assert that tasks rather than jobs will be replaced by automation, citing a recent study on the topic.7 He predicted that, as the data collection and analysis tasks performed by intelligence analysts become increasingly automated through improved machine learning, analysts will be focused on problem solving, intuition, creativity, and situational adaptability. He added that automation will be applied to frequent, high-volume, and routine activities, while humans will focus on abstract activities. “It is really about developing our uniquely human skills,” he said.

___________________

5 For Partnership on AI, see https://www.partnershiponai.org [April 2018]. For Center for Human-Compatible AI, see http://humancompatible.ai [April 2018]. For Future of Humanity Institute, see https://www.fhi.ox.ac.uk [April 2018]. For Center for Ethics and Computational Technologies, see https://www.cmu.edu/ethics-ai [April 2018].

6 The Internet of Things refers to computational technology, networks of sensors, and everyday objects that are connected to the Internet and can exchange data and be controlled remotely.

7 Chui, M., Manyika, J., and Miremadi, M. (2016). Where machines could replace humans—and where they can’t (yet). McKinsey Quarterly, July. Available: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/digital-mckinsey/our-insights/where-machines-could-replace-humans-andwhere-they-cant-yet [March 2018].

Ysursa continued by arguing that humans who know best how to work with computers, rather than the best humans or the best computers, will maximize the potential benefits of AI. He noted that computers are learning to play games, such as AlphaGo, by examining hundreds of thousands of human games, so that machines now exceed human players and identify moves never before identified by humans. He also mentioned that AlphaGo and other new versions of machine learning begin “from scratch” instead of learning from past human games, and reported that humans are improving by learning from the machine.

Ysursa prefers the term “augmented intelligence” to “AI” because it signifies how humans and machines will work together to produce abilities “greater than human or machine.” He pointed to examples of this augmented intelligence, such as use of computer vision in pathology to identify potentially abnormal cells for additional assessment by a human pathologist, noting that augmented intelligence would have the capability to compress the time required to obtain results from days or weeks to hours, potentially saving lives. As additional examples, he noted that augmented intelligence could also be applied to personalized learning or to the prevention of corruption and fraud in nonprofit businesses. However, he acknowledged that AI is unlikely to be applied to every setting or problem, that in some cases, such as sharing the news of a difficult diagnosis in a medical setting, interactions with a machine instead of a human would be unacceptable.

Ysursa also believes that AI will help free resources that can then be applied to greater innovation, and that the development of new products and services will generate demand for new jobs. In fact, he reported, according to the World Economic Forum, 65 percent of children entering first grade today are likely to work in jobs that do not yet exist.8 As an example of jobs that are just beginning to emerge, he cited consultants for the Internet of Things. Other jobs that exist today, he added, may exist in other forms tomorrow. As an example, he observed that truck driving is one of the most common jobs today in every state, but that as autonomous vehicles become more prevalent, truck drivers may not continue working behind the wheel, instead working remotely using virtual reality and operating more than one truck from a central location. Ysursa also expects work in retail settings to focus increasingly on customer experience as e-commerce continues to grow.

With these shifts in roles and jobs, Ysursa continued, some estimates indicate that up to one-third of the workforce will need to change occupa-

___________________

8 World Economic Forum. (2016). The Future of Jobs: Employment, Skills and the Workforce Strategy for the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Global Challenge Insight Report. Available: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Future_of_Jobs.pdf [March 2018].

tions by 2030 (between 16 and 54 million people in the United States). These shifts, he observed, will require training and the development of new skills. Quoting Alvin Toffler, he said, “The most important skill is how to learn and relearn. The illiterate of the 21st century will not be those who cannot read and write, but those who cannot learn, unlearn, and relearn.” He added that many new companies are forming to meet this demand for training, and the sector is growing rapidly. However, he stressed, governments and other stakeholders need to be investing in meeting these workforce needs, especially through public–private partnerships. Yet he noted that many nations that are part of the OECD have instead been decreasing their investments in training since 1993. He cited Singapore and Union-Learn in the United Kingdom as examples of forward-thinking policies and investment in training. In his view, stakeholders need to be engaged intellectually, politically, ethically, and socially to address how the workforce will be transformed over the coming decades.

ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE AND THE PROBLEM OF REPRODUCIBILITY IN SCIENCE

Brian Uzzi, Northwestern University, focused his remarks on how to improve the scientific enterprise. He explained that AI could potentially help solve the problem that many scientific studies produce results that cannot be replicated when the studies are repeated by others, and suggested that the application of AI to the reproducibility problem has broad and potentially useful implications for the analyst workforce. He added that AI has been able to outperform people in identifying which studies are going to be reproducible. Ultimately, he said, “it is really about the mind plus machine partnership because if you put the two together, they do better than either alone.”

Uzzi went on to observe that the problem of reproducibility in science may be significant. He cited one study of this topic indicating that 61 of 100 results from original scientific studies in psychology could not be reproduced.9 He referred to another study of reproducibility in economics making use of the fact that prediction markets not only predicted reproducibility outcomes well but also outperformed market participants’ individual forecasts. Using prediction markets, the researchers found that replication failed for 61 percent of 41 economics studies.10 According to Uzzi, beyond

___________________

9 Open Science Collaboration. (2015). Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science, 349(6251). doi: 10.1126/science.aac4716.

10 Dreber, A., Pfeiffer, T., Almenberg, J., Isaksson, S., Wilson, B., Chen, Y., Nosek, B.A., and Johannesson, M. (2015). Prediction markets in science. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(50), 15343–15347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1516179112.

raising concern that the interpretation of statistically significant findings for many studies may be flawed, this problem of the lack of reproducibility could undermine the validity of statistical hypothesis testing.

Addressing this problem has proven challenging, Uzzi stated. New statistical procedures have been developed in psychology to address it, he noted, but they are difficult to apply and generally counter to an experimental mindset, which emphasizes study design over statistical analysis. He added that others have applied the wisdom of crowds, but that this method also has its detractors. The method does not work well for some types of problems, he explained, is expensive, and is applied after a paper has already been published, which means that using the wisdom of crowds can cause damage before a problem is detected.

Uzzi and his colleagues trained a computerized neural network to recognize papers documenting replicable studies, using 96 studies known to be replicable as a training set. Through machine learning, this AI application could identify which studies were replicable and which were not by examining only the text of the papers. No numbers, statistics, references, graphs, or appendixes were analyzed. Next, the neural network was applied to an out-of-sample set of studies of known reproducibility to test the ability of the AI to identify reproducible studies correctly.

In order to do this, the neural network must first turn the text into vectors, which are co-occurrences of words, Uzzi continued. He explained that the neural network it examines the frequency of co-occurrence of every word, and to make sense of these vectors, identifies patterns, looking at all of the pairings of words. He characterized this process as a “black box,” but ultimately, he noted, the neural network can pare tens of thousands of relationships down to just a few hundred parameters to provide an underlying map of relationships.

Uzzi then described the third step in the process—machine learning. He and his team feed the neural network “map” into different machines, each with different algorithms. Each examines the data and “votes” on whether a paper resembles a replicable or a nonreplicable study. This process is repeated with additional machines, Uzzi explained, resulting in a weighted prediction of whether the paper looks replicable based on its comparison with the training set. The researchers then are able to help train the computers, providing feedback on the accuracy of their predictions to help the AI calibrate and improve its predictive capability over time.

Uzzi presented results comparing humans, AI, and AI and humans working together on their ability to predict the replicability of 100 studies with a known “ground truth.” “The first thing you are going to see here that I found truly amazing,” he said, “is that just by looking at the text, the machine is able to look at evidence that human beings do not.” He noted that human beings use p values and sample sizes, and the results of this re-

search show that AI does not simply duplicate human capabilities; it detects features that humans cannot. In addition, he reported, the results show that humans and AI working together exceed the capability to predict of either working alone by as much as 10 percent. He also showed data demonstrating that AI provides an even greater boost to human capability when the prediction of replicability is more difficult, adding that the importance of that extra capability increases the more papers are analyzed. He noted that AI can also help reduce the time peer reviewing can take, as well as improve its accuracy. He suggested further that researchers could apply AI to help analyze their work before it is submitted for review.

Uzzi and colleagues also conducted research to test the utility of the human–AI partnership with papers not included in the training sample. These included 33 studies replicated by academics (high quality) and 75 replicated by undergraduate students (unpublished). The human–AI partnership made correct predictions for 78 percent of the high-quality replications and 63 percent of the unpublished replications.

In Uzzi’s view, human–AI partnerships can expand capabilities beyond those of humans alone, “expanding human consciousness.” He also believes the techniques applied in his research could be extended to identifying retractions in science, “fake news,” people who are using aliases on the Internet, and propaganda, all difficult problems that often elude human detection.

DISCUSSION

Following the presentations, workshop participants continued to discuss the implications, uses, and potential drawbacks of AI and their intersection with the information presented on diverse teams. One participant posed the question of whether research on the diversity of teams would suggest that one team of 12 tasked with reaching consensus would be better served by being broken up into four teams of 3 that each would generate separate conclusions to be adjudicated. Page responded that this question could apply to either people, artificial neural networks, or a combination of the two. He noted that diversity is less important for solving simple problems with few dimensions than for solving more complex problems. A bigger challenge, he argued, is that people’s predictions or choices are not truly independent from or uncorrelated with one another. Rather, he explained, people overlap in their understanding of and ways of thinking about problems, and “what you really want is people looking at different dimensions and using different models.” He added that his work with diverse teams accords with the findings on AI presented by Uzzi because AI and humans use very different approaches to predicting replicability. “If one person is 10 percent better [at making predictions] and another person

is 8 percent better,” he said, “if those people are pretty different, the two together are probably going to be about 15 percent better. You do not want them converging on the same model.”

Nancy Cooke, Arizona State University, suggested that the diversity and independence necessary for improving prediction could be challenging given the emphasis placed on collaboration to solve problems. She added that people have a tendency to share information they have in common with group members rather than information that is unique to them, and that this “information pooling bias” can affect the final conclusions that people reach. Page observed that consensus discussions often revolve around problems that comprise subproblems, and that when each subproblem is not evaluated independently, an individual may hold a singular view of the problem. This view, he noted, may be misleading as the views of each individual in a group may differ for each subproblem; when these views are averaged, however, it may appear that the group has reached consensus on the problem, yet this is only because the power of diversity has been eliminated. He then suggested that models for decision making in medical settings could illustrate how to address this challenge. Often when a patient presents in an emergency setting with a complex problem, he elaborated, a group of doctors will see the patient sequentially rather than in a group, and will then meet to present and discuss their findings and conclusions to determine the strongest argument.

Eric Eisenberg, University of South Florida, observed that the processes of moving toward consensus and preserving diversity of thought for sensemaking are in tension, especially when it is necessary to avoid acting prematurely or waiting too long to act. Uzzi supported this observation, noting that the emphasis placed on consensus is at odds with the research showing the benefits of diversity of thought. Convincing organizations to recognize the benefits of diversity for decision making may be a lengthy process, he added. Page stressed that diversity in approach, techniques, and causal models is important for problem solving as well as prediction.

Next, the group discussed the jobs people will be holding in the future. Page noted that he and others are in jobs that did not exist when they were undergraduates. Ysursa emphasized that the intelligence analysts of the future will need the ability to learn. Some of this learning can be on the job, he suggested, but the ability to acquire new skills will be necessary to adapt. He added that many of these skills come from the humanities, which, he asserted, are important in addition to coursework in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics.

Contractor asked the group to consider the potential downsides of AI, as well as the challenges it poses to providing explanations for the results it yields. Both Page and Uzzi expressed the view that AI could potentially harm social relationships because it could perform many of the functions

now performed by people, and also serve as a force drawing people apart. “My concern is more about the social fabric of the world being torn apart than about our work lives,” Uzzi said. This is a challenge that should be addressed as AI progresses, he argued.

Ysursa suggested that a challenge for the future would be getting the private sector, the public sector at all levels, and the education system to work together to address a shifting workforce and help ensure that people have the right skills and the right jobs. Given that about two-thirds of American jobs require a high school diploma or less, he added, it will be important to consider how to ensure that people in these jobs are not left behind as the result of increased automation.

Addressing the question of explanation, Uzzi and Page noted that many humans have difficulty explaining how they know something or how they solved a problem. Uzzi believes explanations will be derived as humans learn to work with AI and understand the tacit knowledge it possesses. However, Page believes that ultimately, algorithms will be developed to examine neural networks and provide explanations. Goodwin noted that the ability to provide a compelling explanation for a conclusion is a vital component of an analyst’s job. Uzzi explained that AI can serve in a personal consulting role. It can check a person’s predictions against AI predictions, he observed, allowing the human user to work with the AI in an iterative process to improve decision making. He added that it may even be used to generate text for reports automatically.

Hall agreed that human–machine interactions, rather than AI alone, appear to be most promising. She noted that experiments attempt to isolate the effects of particular variables, but results from such isolation, in a reductionist sense, can differ from real-world complexity in important ways. She believes AI can help researchers make sense of the ways in which many variables predict different outcomes, but cautioned that current algorithmic strategies may be limited by the sets of data on which they were used to train the IA system. Therefore, ongoing training of the systems will likely require extensive human involvement, updating them with new information to optimize associated algorithms, particularly as the complexity of the problem increases.

Page observed that AI can yield sets of predictions that may be accurate but fail to provide a coherent narrative. Uzzi explained that although any one AI application can yield very accurate predictions, consistency and confidence in their collective predictions increase with the diversity of the algorithms working on a problem.

FINAL REMARKS

Contractor closed the workshop by providing his views on how the day’s discussions related to the job of the intelligence analyst. The lessons learned throughout the day, he said, suggest both short-term and long-term goals over the next decade. He suggested that advancing the process of selection, recruiting, and training may be attainable in the short term, while understanding teams and technology’s role in teams is another important next step. He identified understanding augmented intelligence (humans plus AI) as an important emphasis of the presenters. Therefore, he said, those considering how to train the workforce of the future should consider how those workers will interface with intelligent technology that augments their own cognition.

Contractor cited as another key point the need for additional work to better understand how to make predictions and how to represent them as a distribution of possible outcomes with different probabilities of occurring. Finally, he stressed that the ability to communicate well both face-to-face and through writing will continue to be important.