3

Voting in the United States

In the United States, federal elections occur every 2 years in even-numbered years.1 Federal regulation of elections is limited, most importantly governing voting rights and campaign finance and affecting when elections for Congress are held. The major aspects of election administration are determined by state and local laws, and elections are overseen by state and local administrators. Although local control over elections leads to variations in specific processes, elections follow the same general process throughout the country (see Figure 3-1).

During each federal election, all 435 members of the House of Representatives are elected for 2-year terms. Senators are elected for staggered 6-year terms. This means that roughly one-third of the Senate is elected every 2 years. Presidential elections are held concurrently with House and Senate elections every fourth year.

State and local contests, including ballot initiatives and referenda, often appear on the ballot alongside federal contests in even-numbered years. However, a few states hold state elections in odd-numbered years,2 and it is common for local governments to hold elections in the spring, rather than in the fall.

Elections for most offices have a preliminary race wherein the initial field of candidates is winnowed to a smaller number. Most commonly,

___________________

1 Special elections for members of Congress may be held to fill vacancies in both even and odd years.

2 Five states, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, New Jersey, and Virginia, hold major state elections in odd-numbered years.

SOURCE: Adapted from U.S. Election Assistance Commission, 2016 Election Administration and Voting Survey (EAVS), June 29, 2016, p. 4. The original image, which is available at: https://www.eac.gov/assets/1/6/2016_EAVS_Comprehensive_Report.pdf, is the work of the U.S. Election Assistance Commission, taken or made during the course of an employee’s official duties. As a work of the U.S. federal government, the image is in the public domain.

NOTE: This figure is provided as a general illustration of the election process. It does not include all components of the process, e.g., poll site selection.

political parties hold so-called primary elections. In primary election scenarios, candidates compete to stand as their party’s single nominee in the general election.3 In jurisdictions that hold non-partisan elections, a first round known as a preliminary election is held to reduce the number of candidates prior to the general election.

The large number of elections and the numerous contests on many ballots create an administrative challenge to election administrators. This challenge is a principal driver for automation in American election administration.

The details of election administration vary considerably across states and local governments. Variation exists with respect to levels of funding,4 human resources, how ballots are cast, and how votes are captured and tabulated. Furthermore, federal and state laws govern how military and overseas citizens may cast their votes in absentia.5 The result is a diverse and complex system of elections and wide variation in the training and capability of election administrators and staff who administer elections.

On Election Day, problems can arise when the lines to vote are too long, when voting rolls are inaccurate, when voting machines break down, when ballots are poorly designed, when physical accessibility is limited, when precincts run out of ballots, when poll workers are poorly trained, or when election systems are compromised.6 Equipment failure, inadequate training, or poor ballot design can lead to long wait times. Inadequate access for voters with limited English proficiency or for voters with disabilities may be the result of insufficient resources applied to the needs of those communities. Inaccurate voter registration lists may stem from the absence of comprehensive and current voter registration databases. Election systems may be vulnerable to intrusions that target voter rolls or voting systems.

To ensure that the results of an election are representative of the will of the people, every valid vote must be accurately counted. To achieve this, eligible citizens must be able to obtain their ballots, cast their votes for their candidates of choice, and have those votes recorded and tabulated accurately. At the same time, repeat voting and voting by ineligible individuals must be deterred and prevented.

___________________

3 In a few states, for some offices, political parties still hold conventions to nominate party representatives in the general election.

4 It is extremely challenging to calculate the cost of election administration in the United States (see Appendix D).

5 The primary federal laws affecting voting by military and overseas civilians are the Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act (UOCAVA), Pub.L. 99-410, and the Military and Overseas Voter Empowerment Act (MOVE), Pub.L. 111-84. Both of these laws are overseen by the Federal Voting Assistance Program (FVAP), which is a part of the U.S. Department of Defense. See https://www.fvap.gov.

6 In addition to reliability issues and issues relating to the management of the flow of voters, Election Day problems may include issues related to election integrity and voter privacy.

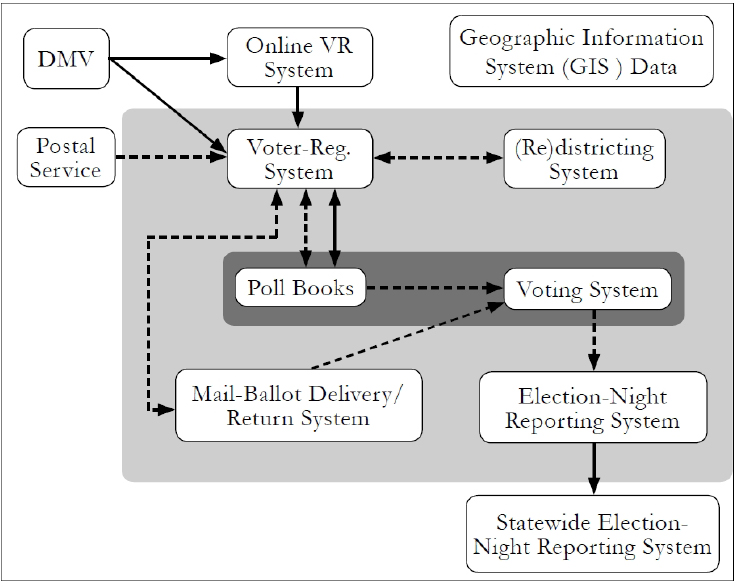

In modern elections, the voting process is largely dependent on technology-based systems known as election systems. These systems collect, process, and store data related to all aspects of election administration.7 Election systems include public election websites (e.g., state “my voter” pages),8 voter registration (VR) systems, voting systems (the means through which voters cast their ballots), vote tabulation systems, election night reporting systems, and auditing systems (see Figure 3-2).9

In the United States, votes are cast: (1) in person; (2) via mail;10 or (3) digitally from a remote location.11 Regardless of how a vote is cast, each voter is assigned to a voting district, typically called a precinct, which is a bounded geographic area wherein all individuals generally vote for the same set of candidates and issues. In all cases, an individual must meet eligibility requirements and, in most states, must be registered to vote before he or she may be able to cast a lawful ballot.12

VOTER REGISTRATION, VOTER REGISTRATION DATABASES, AND POLLBOOKS

Voter registration plays a central role in elections in 49 states and the District of Columbia,13 as in these locations, a voter must be registered for his or her vote to count.14 As a general rule, voters register to vote in a spe-

___________________

7 King, Merle, Kennesaw State University, PowerPoint presentation to the committee (Slide 5), June 12, 2017, New York, NY. The presentation is available at: http://sites.nationalacademies.org/cs/groups/pgasite/documents/webpage/pga_180929.pdf.

8 Georgia’s My Voter Page, for instance, provides information on the state administration of elections and elections results and allows individuals to check their voter registration status, mail-in application and ballot status, and provisional ballot status; to locate poll and early voting locations; and view information about elected officials and sample ballots for upcoming elections. See https://www.mvp.sos.ga.gov/MVP/mvp.do.

9 King, Slide 5.

10 Vote-by-mail ballots are often returned by voters at central drop-off points unconnected to the United States Postal Service. See discussion below addressing vote-by-mail directly.

11 Digital return of ballots for counting is rare, and is primarily done in the case of some overseas ballots in a limited number of jurisdictions.

12 North Dakota does not require voter registration. In some jurisdictions, registration may be automatic or available at the time of voting.

13 Throughout this report, reference is made to statistics that include American states and the District of Columbia but not U.S. territories or commonwealths. This is due to the fact that some of the most authoritative data sources pertaining to election administration are inconsistent in the inclusion of data from territories/commonwealths.

The U.S. Election Assistance Commission’s Election Administration and Voting Survey cited in this report, includes data provided by four territories—American Samoa, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands—but does not include data from the Northern Mariana Islands.

14 As mentioned in a previous footnote, North Dakota does not require voter registration. Rather, in North Dakota, voters need only provide photo identification and proof of age and residency at the time they vote.

SOURCE: Stewart, Charles III, “The 2016 U.S. Election: Fears and Facts About Electoral Integrity,” Journal of Democracy, April 2017, Vol. 28, No. 2, p. 56, Figure 2. © 2017 National Endowment for Democracy and Johns Hopkins University Press. Reprinted with permission of Johns Hopkins University Press.

NOTES: This schematic of voting information-system architecture is based on the work of Merle King. As a schematic, it does not include all conceivable election systems, e.g., systems used to pre-program ballot designs. For King’s original figure, see http://www.nist.gov/sites/default/files/documents/itl/vote/tgdc-feb-2016-day2-merle-king.pdf (p. 14).

Arrows depict the direction of information flow between component systems. Solid lines indicate flows that typically rely on the Internet or other networks that are connected to the Internet; dashed lines indicate information flows that typically are “air-gapped” from outside networks. The dark box indicates systems that are typically deployed in individual polling places; the light-gray box indicates systems that are typically centralized in a local jurisdiction’s election office.

cific geographic jurisdiction that is determined from the residential address that they provide for the purpose of voting. The voting address of record determines the voting district wherein a voter may cast a ballot. States set deadlines for when a voter must register to participate in an election.

Individuals may register to vote in many ways. They may register in person at election offices or at temporary sites set up in public places. They may register at departments of motor vehicles, departments of human services, and public assistance agencies.15 All states offer the option to register to vote by mail. In 37 states and the District of Columbia, individuals can register to vote via the Internet so long as the registrant’s information can be matched to information that was provided when a driver’s license or other state-issued identification was issued.16 Overseas voters and members of the U.S. armed forces and their dependents may obtain registration forms via electronic transmission.17 Fifteen states currently allow same-day voter registration, and another, Hawaii, has enacted same-day registration provisions that take effect in 2018.18 Nine states and the District of Columbia have introduced automatic voter registration (AVR).19

The 2002 Help America Vote Act (HAVA) established a requirement that all states implement a “single, uniform, official, centralized, interactive computerized statewide voter registration list.” The list is to be administered by the state and contain the “name and registration information of every legally registered voter in the state.”20 To function as intended, each state voter registration database (VRD) must (1) add new registrants to the VRD; and (2) update information about voters (e.g., name and address changes).21 These tasks require both good data and good matching procedures.

___________________

15 The “Election Administration and Voting Survey: 2016 Comprehensive Report” (EAVS) states that, while state motor vehicle offices are the most common place where individual register to vote with 32.7 percent of all registrations, online registration has increased dramatically over the past 4 years (see p. i).

16 See http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/electronic-or-online-voterregistration.aspx. Oklahoma has passed legislation to create online voter registration, but has yet to implement online voter registration.

17 A subtitle of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2010 (Pub.L. 111-84), the Military and Overseas Voter Empowerment Act (“MOVE” Act), required each state to designate not less than 1 means of electronic communication…for use by absent uniformed services voters and overseas voters who wish to register to vote or vote in any jurisdiction in the State to request voter registration applications.” See Sec. 577.

18 See http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/same-day-registration.aspx.

19 “Automatic voter registration is an ‘opt out’ policy by which an eligible voter is placed on the voter rolls at the time they interact with a motor vehicle agency (or, in a few states, with other government agencies) unless they actively decline to be registered.” See http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/automatic-voter-registration.aspx.

20 HAVA § 303, 52 U.S.C. § 21083.

21 Because voter registration lists are maintained by individual states, when a voter moves from one state to another, registration information does not follow the voter. As a consequence, the voter must register in his or her new state. Although voter registration forms ask new registrants whether they are registered in another state, the law does not require a voter to answer this question. As a result, it is common for individuals to appear on registration rolls in more than one state, even though they are only eligible to vote in one.

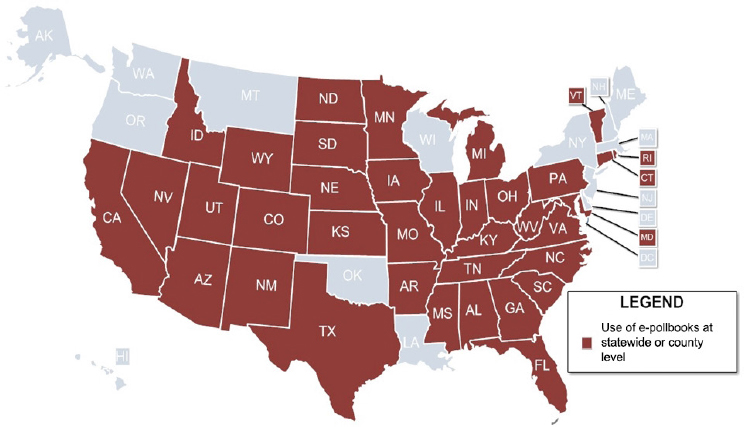

SOURCE: Adapted from Matthew Masterson, U.S. Election Assistance Commission, presentation to the committee, April 5, 2017, Washington, DC. The original image, which is available at: http://sites.nationalacademies.org/cs/groups/pgasite/documents/webpage/pga_178367.pdf, is the work of the U.S. Election Assistance Commission, taken or made during the course of an employee’s official duties. As a work of the U.S. federal government, the image is in the public domain.

The VRD is used to prepare pollbooks. Pollbooks are used at polling places to verify an individual’s eligibility to vote at the location where they have appeared. Traditionally, pollbooks were lists of registered voters that were printed and distributed to polling places in advance of an election, but increasingly, jurisdictions are using electronic pollbooks (EPBs or e-pollbooks). E-pollbooks are typically housed on laptops or tablets. Some contain local, static lists in electronic form, while others allow access to information in voter registration databases via a real-time Internet connection. According to the U.S. Election Assistance Commission, 36 states now use e-pollbooks (see Figure 3-3) in at least some of their jurisdictions.

BALLOTS

Across the country, jurisdictions use a variety of ballots (paper, card, or electronic) to present candidates and issues to voters. Ballots are often designed under multiple “constraints, including state laws on structure and ballot access rules, minority language requirements for jurisdictions covered by the VRA, the type of voting equipment used, and the various

combinations of offices and issues for which people are eligible to vote.”22 Such constraints complicate the ballot design process.

A provisional ballot may be used to record the individual’s vote if a voter’s eligibility to vote cannot be established or if an election official asserts that the individual is not eligible to vote. Provisional ballots are required under HAVA, but states establish the criteria under which an individual may obtain a provisional ballot (see Appendix E).23 Votes cast with provisional ballots are counted only after a voter’s eligibility to vote has been established.

POLL WORKERS

On Election Day, paid temporary workers assist in polling place operations. These poll workers may verify the identity of a voter; assist voters in signing the register, affidavits, or other documents required to cast a ballot; provide a ballot to a voter; set up a voting machine; or carry-out other functions as dictated by state law.24

Many jurisdictions have difficulty recruiting and training poll workers because this “seasonal” work involves “long hours, low pay, workday conflicts that limit the recruiting pool, and increasing technological demands for special skills.”25 In 2016, “46.9 percent of responding jurisdictions reported having a somewhat difficult or very difficult time recruiting poll workers, compared with 22.7 percent that reported having a somewhat easy or very easy time. States and territories reported deploying an aver-

___________________

22 Montjoy, Robert S., “The Public Administration of Elections,” Public Administration Review, September-October 2008, pp. 792-793.

23 See http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/provisional-ballots.aspx. Idaho, Minnesota, New Hampshire, North Dakota, Wisconsin, and Wyoming were exempt from the HAVA provisional ballot requirement as these are states that offered same day registration in 2002, the year HAVA was enacted. Nonetheless, some states that are not required to use provisional ballots have provisions for their use, and several states used provisional ballots before HAVA was enacted.

States where all ballots are returned by mail provide for the casting of provisional ballots. In Oregon, if a voter has a question about his or her eligibility to vote, he or she may request a provisional ballot from any Oregon County Elections Office (see http://sos.oregon.gov/elections/Documents/SEL113.pdf). In Washington, provisional ballots may be cast at any voter service center (see https://wei.sos.wa.gov/county/spokane/en/pages/FrequentlyAskedQuestions.aspx). Likewise, in Colorado, provisional ballots may be cast at voter service and polling centers (see https://www.sos.state.co.us/pubs/elections/FAQs/ElectionDay.html).

24 “2016 Election Administration and Voting Survey” (EAVS), p. 13.

25 U.S. Government Accountability Office, “Elections: Perspectives on Activities and Challenges Across the Nation” (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 2001), available at: https://www.gao.gov/new.items/d023.pdf.

In addition, poll workers must ensure compliance with numerous polling place mandates.

age of 7.8 poll workers per polling place for Election Day 2016.”26 Data provided on approximately 53 percent of poll workers who served in the 2016 federal election indicates that the poll worker population is skewed toward older individuals. Most poll workers are over age 40, 32 percent were between the ages of 61 and 70, and 24 percent were 71 years of age or older.27

While the qualifications required of poll workers vary by state, poll workers must often be registered to vote in the precinct or county in which they will serve. They must often also meet specific bilingual language requirements.

CASTING A VOTE

Voting Systems and the Voting Technology Marketplace

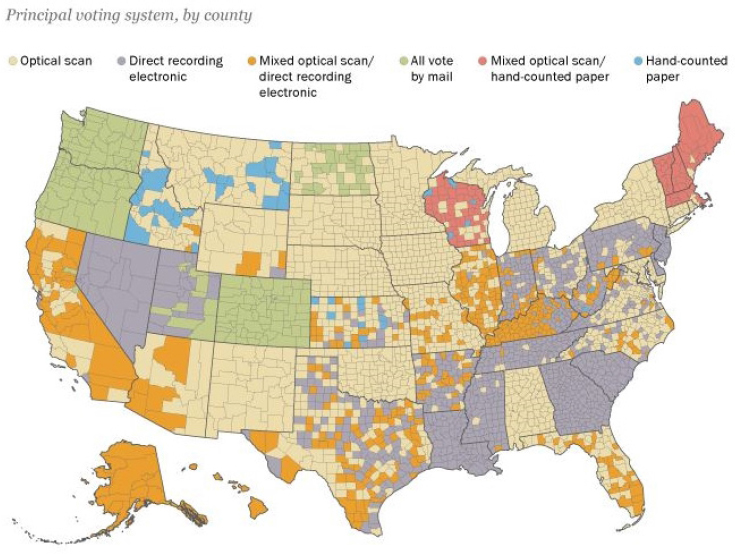

In the United States, voters cast votes using a variety of voting systems (see Figure 3-4). As discussed in Box 3-1, voting systems can be distinguished by the means of casting and tabulating votes. Voters have long cast their votes on paper (see Box 3-2), and paper remains the most commonly used medium in vote casting. The great majority of paper ballots are marked by the voter, and voter responses are tabulated using computerized optical scanners in a manner that is similar to systems used to record answers to standardized tests.28 Alternatively, ballot-marking devices (BMDs) may be used in conjunction with optical scanners. In this scenario, a voter uses a touchscreen or keypad to select his or her choices on a digital display. When the voter has completed the selection process, a paper copy of the completed ballot is printed. This ballot can be scanned optically or digitally, but can also be read by humans. BMDs do not tabulate votes or record them in a computer’s memory. Instead, the paper ballots are scanned and tabulated using a separate device.

Optical scan systems were the most commonly used voting system in U.S. counties in the 2016 election (see Table 3-1). In about one-third of U.S. counties, voters cast their ballots using BMDs or Direct Recording Electronic (DRE) systems where the voter casts his or her ballot using an electronic system (often similar to an ATM) (see Table 3-1). With DREs, ballots are then counted internally by the system’s computer. In a small percentage of counties, voters either cast paper ballots that were manu-

___________________

26 “2016 Election Administration and Voting Survey” (EAVS), p. 13.

27 Ibid, p. 14.

28 There are important differences. With standardized tests, for example, there are examination booklets with questions and separate sheets where students mark their selected answer by filling in ovals that correspond with their intended answer. With ballots, responses are marked by filling in ovals adjacent to the names of candidates or other choices.

SOURCE: Desilver, Drew, “On Election Day, Most Voters Use Electronic or Optical-Scan Ballots,” Pew Research Center, November 8, 2016. Pew Research Center created the figure using data from the Verified Voting Foundation.

TABLE 3-1 Types of Voting Systems Used in the United States in 2016

| Voting System | Percent of U.S. Counties Using System |

|---|---|

| Hand Counted Paper Ballot | 1.54% |

| Optical Scan | 62.78% |

| Electronic (DRE or BMD) | 32.85% |

| Mixed | 2.69% |

SOURCE: Brace, Kimball, President, Election Data Services, Inc., “The Election Process from a Data Perspective,” presentation to the Presidential Advisory Commission on Election Integrity, September 12, 2017, Manchester, NH, available at: https://www.electiondataservices.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/BracePresentation2PenseCommAmended.pdf.

ally counted or voted with a mixture of systems (see Table 3-1). In many instances, marked ballots are submitted by mail and tabulated at a central location.

HAVA requires that each polling place used in a federal election

be accessible for individuals with disabilities, including nonvisual accessibility for the blind and visually impaired, in a manner that provides the same opportunity for access and participation (including privacy and independence)29 as for other voters . . . through the use of at least one

___________________

29 Participation also includes the ability to cause one’s own ballot selections to be recorded, verifying that one’s ballot selections are correctly recorded, and the casting of one’s self-verified ballot.

direct recording electronic voting system or other voting system equipped for individuals with disabilities at each polling place.30

Practically speaking, this means that even in local jurisdictions where ballots are typically cast by paper, DREs or other accessible voting systems are available in all polling places to comply with HAVA’s accessibility requirements.

Further, HAVA requires that voting systems provide alternative language accessibility.31 HAVA does not, however, provide a private right of action for voters with disabilities to pursue enforcement of either the disability or alternative language access provisions.32 The 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) may, however, provide a private right of action.33

Currently, there are only a few manufacturers of election systems. In the United States, three firms comprise 92 percent of the voting system market by voter reach.34 The largest firm has about 460 employees.35 This concentration represents a potential security risk, as a successful malicious infiltration of a single company could affect the operations of a significant portion of the election systems in use.

Certification of voting systems is an authority that rests with the states, although an important role in certification is played by the U.S. Election Assistance Commission (EAC) and the National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST). Working collaboratively, the EAC and NIST maintain the Voluntary Voting System Guidelines (VVSG), which are a set of specifications against which voting systems are tested and which states may voluntarily adopt, in part or as a whole.36 Several states require either testing to meet federal standards or testing by a federally accredited laboratory, and many states require full federal certification. In addition, many states have certification standards that meet or exceed federal standards (see Table 3-2).

___________________

30 HAVA § 301(a)(3), 52 U.S.C. § 21081(a)(3).

31 See HAVA § 301(a)(4), 52 U.S.C. § 21081(a)(4).

32 See Golden, Diane Cordry, Association of Assistive Technology Act Programs, PowerPoint presentation to the committee (Slide 3), June 13, 2017, New York, NY. The presentation is available at: http://sites.nationalacademies.org/cs/groups/pgasite/documents/webpage/pga_180932.pdf.

A private right of action is the right to bring a lawsuit.

33 42 U.S.C. §§ 12101 et seq.

34 See University of Pennsylvania Wharton School, “The Business of Voting: Market Structure and Innovation in the Election Technology Industry,” 2016, available at: https://publicpolicy.wharton.upenn.edu/live/files/270-the-business-of-voting.

The three firms are Elections Systems & Software, Dominion Voting Systems, and Hart InterCivic.

35 Ibid. That firm is Elections Systems and Software.

36 The current version of the Voluntary Voting System Guidelines, VVSG1.1, was adopted by U.S. Election Assistance Commission commissioners on March 31, 2015. It is anticipated that the next iteration of the guidelines, VVSG 2.0, will be adopted in 2018. See https://www.eac.gov/voting-equipment/voluntary-voting-system-guidelines/.

TABLE 3-2 Voting Systems Certification Standards by State

| States Requiring Testing to Federal Standards | States Requiring Testing by a Federally Accredited Laboratory | States Requiring Full Federal Certification (in Statute or Rule) |

|---|---|---|

| Connecticut, DC, Hawaii, Indiana, Kentucky, Nevada, New York, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia | Alabama, Arkansas, Arizona, Colorado, Illinois, Iowa, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, New Mexico, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Utah, and Wisconsin | Delaware, Georgia, Idaho, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, South Carolina, South Dakota, Washington, West Virginia, and Wyoming |

The following four states refer to federal agencies or standards, but do not fall into the categories above: Alaska,a California,b Kansas, and Mississippi. c, d

The following eight states have no federal testing or certification requirements. Statutes and/or regulations make no mention of any federal agency, certification program, laboratory, or standard; instead these states have state-specific processes to test and approve voting systems: Florida, Maine, Montana, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Oklahoma, and Vermont.

a In Alaska, the state elections director may consider whether the Federal Election Commission (FEC) has certified a voting machine when considering whether the system shall be approved for use in the state (though FEC certification is not a requirement).

b In California, the Secretary of State adopts testing standards that meet or exceed the federal voluntary standards set by the U.S. Election Assistance Commission.

c Mississippi requires that Direct Recording Electronic (DRE) systems shall comply with the error rate standards established by the FEC (though other standards are not mentioned).

d Even states that do not require federal certification typically still rely on the federal program to some extent and use voting systems created by vendors that have been federally certified.

SOURCE: Adapted from National Conference of State Legislatures, “Voting System Standards, Testing and Certification,” available at: http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/voting-system-standards-testing-and-certification.aspx.

The software used to operate voting systems is generally proprietary; its purchase is bundled with the purchase of hardware and maintenance services.37 The software installed on commercial election systems typically runs on a commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) operating system that is usually proprietary. There is a movement by some election administrators to

___________________

37 Proprietary software is owned by a company or individual. The owner(s) of proprietary software typically place restrictions on how the software may be used. Users of proprietary software and other individuals outside of the company generally do not have access to the software’s source code. As a result, they cannot modify the source code or view it to identify flaws or vulnerabilities.

Some states require the code to be escrowed and accessible for inspection in specified circumstances.

develop or adopt open-source or publicly owned software that is available in source code form with a license, allowing the source code to be studied, modified, and distributed without limitation.38 Open-source software is typically installed on commercial off-the-shelf equipment.

Election administrators take many factors into account when purchasing voting systems (see Box 3-3). Jurisdictions typically enter into software licensing and maintenance agreements with the vendors of commercial equipment. In exchange, the vendor maintains and provides hardware support for the election system and provides support for and upgrades to its proprietary software. In many jurisdictions, commercial vendors also provide the digital ballot definitions that enable their equipment to present, print, scan, and tabulate the jurisdiction’s election-specific ballots for those casting votes.

Absentee Voting and Voting by Mail

Historically, voters were required to cast their ballots in person at their assigned polling places on Election Day. Absentee voting was originally developed to allow soldiers deployed away from home to vote. Eventually, the use of absentee ballots was extended to civilian voters, utilizing the mails to transmit and return ballots.39

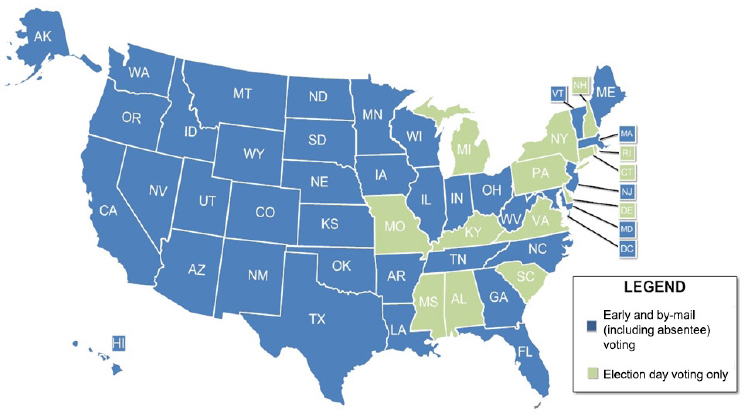

Originally, voters had to provide an acceptable excuse to cast an absentee ballot, e.g., illness or travel. Today, however, most states have broadened voting mechanisms for the convenience of voters. Most states allow early in-person voting or voting by mail without requiring an excuse (see Figure 3-5).40

Three states, Washington, Oregon, and Colorado, have adopted mail-only voting. In these states, ballots are mailed to all registered voters. Voters may return completed ballots either by mail or in person. In 2016, most voters in these three states returned their ballots in person, rather than via

___________________

38 Travis County in Texas, San Francisco, and Los Angeles County in California are three jurisdictions that are exploring the use of open-source operating systems. The state of New Hampshire recently adopted an open-source system called One4All based upon open-source software called Prime III developed at the University of Florida. Dr. Juan E. Gilbert, who serves as a member of the committee that authored the current report, was a developer of Prime III.

Software developers may also opt to make underlying source code available for others to review but not to modify without explicit permission. This scenario is sometimes referred to as disclosed source.

39 Inbody, Donald S., The Soldier Vote: War, Politics, and the Ballot in America (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016).

40 Some states call all voting by mail early voting, whereas others refer to in-person early voting as a form of absentee voting. The use of different terms for what are essentially the same processes lends confusion to discussions of absentee or early voting.

SOURCE: Adapted from Masterson, Matthew, U.S. Election Assistance Commission, presentation to the committee, April 5, 2017, Washington, DC. The original image, which is available at: http://sites.nationalacademies.org/cs/groups/pgasite/documents/webpage/pga_178367.pdf, is the work of the U.S. Election Assistance Commission, taken or made during the course of an employee’s official duties. As a work of the U.S. federal government, the image is in the public domain.

NOTE: For states designated as allowing “Election Day voting only,” ballots received early may be cast if specific criteria are met.

the mail.41 Thus, it is actually a misnomer to refer to these as “vote-by-mail” states. It is more accurate to refer to them as “ballot-delivery-by-mail” states.

Two other states, California and Utah, are moving toward mail-only elections. Currently, most voting in these states is conducted by mail.42 In

___________________

41 Stewart, Charles III, “2016 Survey of the Performance of American Elections: Final Report,” 2017, p. 26. Dr. Stewart is a member of the committee that authored the current report.

42 Masterson, Matthew, U.S. Election Assistance Commission, presentation to the committee, April 5, 2017, Washington, DC. See also “2016 Election Administration and Voting Survey” (EAVS), p. 9.

There are accommodations for in-person voting in the three states that conduct their elections by mail. In Washington, every county has a vote center for in-person voting (see https://www.sos.wa.gov/elections/faq_vote_by_mail.aspx). In Oregon, each County Elections Office provides privacy booths for voters who want to vote in person or voters who need assistance (see https://multco.us/file/31968/download). In Colorado, voters have the option to vote in person at a county Voter Service and Polling Center (VSPC) (see https://www.sos.state.co.us/pubs/elections/FAQs/ElectionDay.html).

2016, 52 percent of California’s ballots and 68 percent of Utah’s ballots were cast by mail.43

In addition, the Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act (UOCAVA) allows “U.S. citizens who are active members of the Uniformed Services, the Merchant Marine, and the commissioned corps of the Public Health Service and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, their eligible family members and U.S. citizens residing outside the United States” to vote using absentee ballots.44

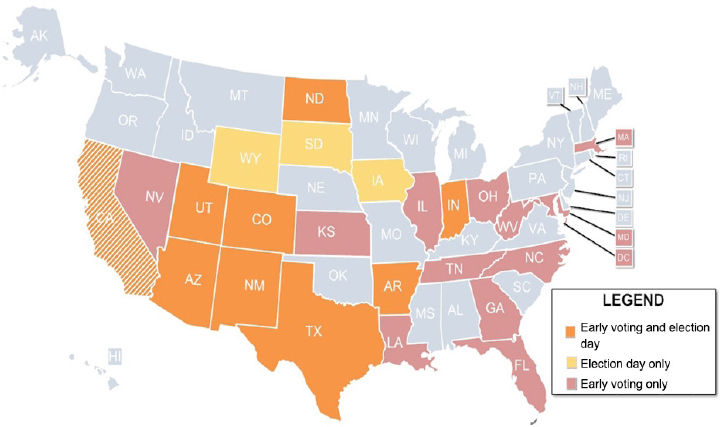

Vote Centers

Traditionally, voters cast votes at assigned polling places within their specific precinct. Recently, in order to facilitate more efficient voting, numerous states have moved to consolidate voting in vote centers (see Figure 3-6). A vote center serves as a jurisdictional hub where any voter registered in that jurisdiction may vote, regardless of the precinct in which the voter resides.45 Three states, Wyoming, South Dakota, and Iowa, allow jurisdictions to use vote centers only on Election Day. Twelve states and the District of Columbia allow jurisdictions to use vote centers during early voting only,46 and eight states allow the use of vote centers during early voting and on Election Day.47 California has authorized the use of vote centers starting in 2018.48

Collection Points for Ballots Received Early

Some jurisdictions provide secure facilities where voters may deposit ballots received early either before or on Election Day.

COUNTING VOTES

Votes are counted in three principal ways: (1) votes cast on paper ballots may be counted manually; (2) paper ballots may be scanned and the votes counted digitally; and (3) votes cast using electronic systems may be

___________________

43 These percentages were calculated using the U.S. Census Bureau’s, “Current Population Survey Voting and Registration Supplement,” 2016. Utah did not report in the “2016 Election Administration and Voting Survey” (EAVS) the number of ballots cast by mail, which necessitated the use of a survey-based method to estimate vote-by-mail usage.

44 52 U.S.C. §§ 20301 et seq.

45 See, for example, Colorado Revised Statutes 1-4-104 (49.8).Georgia, I

46 The states are Florida, Georgia, llinois, Kansas, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Nevada, North Carolina, Ohio, Tennessee, and West Virginia.

47 The states are Arizona, Arkansas, Colorado, Indiana, New Mexico, North Dakota, Texas, and Utah.

48 See http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/vote-centers.aspx.

The California Voter’s Choice Act allows voters to cast ballots at vote centers in a limited number of counties beginning in 2018. See http://www.sos.ca.gov/elections/voters-choice-act/.

SOURCE: Masterson, Matthew, U.S. Election Assistance Commission, presentation to the committee, April 5, 2017, Washington, DC. The original image, which is available at: http://sites.nationalacademies.org/cs/groups/pgasite/documents/webpage/pga_178367.pdf, is the work of the U.S. Election Assistance Commission, taken or made during the course of an employee’s official duties. As a work of the U.S. federal government, the image is in the public domain.

counted digitally. In the latter case, a paper ballot is not employed. When paper ballots are scanned, the results are tabulated, and printed, after the close of polls. The scanning may occur in one of two places—in the precinct where the ballots were cast, or in a central counting facility.

At the end of Election Day, if ballots were counted in the precinct, unofficial vote totals are communicated to a central election office through one of several means. These include paper printouts, hand-written paper forms, telephone, modem, and computer memory cards. Either on Election Day or soon thereafter, official returns are most likely to be communicated to the central office by traditional means, e.g., in paper form through the mails or via couriers.

Multiple safeguards are put in place to protect against tampering with vote counts.49 These safeguards start at the point where the votes are

___________________

49 In many states, safeguards were written into legislation prior to computerization and may not, therefore, offer the protections that they once did.

counted. States generally allow votes to be counted in the presence of the public, although these same laws may give precedence to some parts of the public (such as representatives of political parties) or require that the public be physically distanced from the vote counters. States commonly require that precinct vote returns be posted at the precinct once the counting is finished. This allows the public, candidates, and political parties an opportunity to record a precinct’s vote count and subsequently compare it to totals published later.

States have laws that mandate the protection of ballots and other equipment used in elections, in the event a recount is necessary or if a count were to otherwise be called into question.

Ballots received by mail are typically sent directly to the central elections department. Mail-in ballots generally have two envelopes: an inner, plain envelope for the ballot; and an outer envelope with a signature line. The completed ballot is placed in the inner envelope, and the envelope is sealed. This envelope is then placed in the outer envelope, the outer envelope is sealed, and the voter signs on the signature line. When the ballot is received by the elections department, officials ensure that the signature on the outer envelope matches a signature on file with the department. If the signature matches, the inner envelope is removed and placed apart from the outer envelope. The inner envelopes are then opened and counted by an optical-scan reader or other mechanism.

CERTIFYING RESULTS

The tallies reported on election night are not the final results of the election. Instead, the official results of an election are not determined until the election returns have been validated through a process known as canvassing.50 This validation involves not only rechecking the results reported on election night, but also adjudicating the status of provisional ballots and including ballots that may have arrived by mail after Election Day. Deadlines for the receipt of mail ballots vary by states, with many allowing mail ballots to be counted if they are postmarked before Election Day and arrive within a specified time after Election Day.51 Once all vote numbers have been reconciled, the local election authority certifies the election for the jurisdiction and generates a report with the official vote count.52 Results of statewide contests are further certified by state authorities, such as a state

___________________

50 U.S. Election Assistance Commission, “Quickstart Management Guide: Canvassing and Certifying an Election,” October 2008, p. 3, available at: https://www.eac.gov/assets/1/6/Quick%20Start-Canvassing%20and%20Certifying%20an%20Election.pdf.

51 For a list of state deadlines from the 2016 election, see https://web.archive.org/web/20161108023142/https://www.vote.org/absentee-ballot-deadlines/.

52 Ibid.

elections board. All states have laws that provide mechanisms to contest election results and to recount votes when election results are close.

ELECTION AUDITING

Most local jurisdictions conduct audits after an election, either because auditing is mandated by law or because local officials have independently adopted an audit requirement.53,54 Some audits scrutinize the processes followed by election officials to ensure that proper procedures were followed. Such audits are referred to as performance audits.

Elections audits also may be conducted to reconcile the record of the number of voters who signed precinct pollbooks with the total number of ballots cast in the precinct and to check that the results of an election are consistent with the physical or electronic record that is produced by voters.

One recently developed class of post-election audits is risk-limiting audits.55 Risk-limiting audits provide statistical assurance that a reported outcome is the same as the result that would be obtained if all ballots were examined by hand by ensuring that a different reported outcome has a high probability of being detected and corrected. Risk-limiting audits are typically performed by examining a random sample of the cast paper ballots and comparing their contents to expected results. Increasingly, election administrators are looking to risk-limiting audits to help ensure the accuracy and security of the vote and increase confidence in the outcome of elections. In 2018, Colorado will become the first state to conduct risk-limiting audits for a statewide election.56

___________________

53 For a discussion of current state post-election audit practices, see, for example, National Conference of State Legislatures, “Post-Election Audits,” available at: http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/post-election-audits635926066.aspx.

54 Equipment used in elections may also undergo various forms of testing to attempt to improve integrity and security of election systems. These may include both pre-election and post-election testing of the hardware and software components of election systems. Pre-election testing of voting equipment is referred to as “logic and accuracy testing.” Such pre-election testing is conducted primarily as an assurance against non-adversarial errors and breakdowns impacting accuracy.

55 Philip B. Stark, Associate Dean, Division of Mathematical and Physical Sciences and Professor of Statistics, University of California, Berkeley, invented risk-limiting audits. Jennie Bretschneider, Office of the California Secretary of State; Sean Flaherty, Iowans for Voting Integrity; Susannah Goodman, Common Cause; Mark Halvorson, Citizens for Election Integrity Minnesota; Roger Johnston, Argonne National Laboratory; Mark Lindeman, Columbia University; Ronald L. Rivest, a member of the committee that authored the current report; and Pam Smith, Verified Voting, contributed to the development of Stark’s work.

56 Morrell, Jennifer, Arapahoe County (CO) Elections Director; Hilary Hall, Boulder County (CO) Clerk and Recorder; and Amber McReynolds, Denver (CO) County Elections Director, presentation to committee, December 7, 2017, Denver, CO.

CONCLUSION

For processes from voter registration to the casting and tabulation of votes, election administrators are responsible for the acquisition, maintenance, and oversight of numerous systems that often interact in complex ways. Each system plays an integral part in ensuring that the results of an election are consistent with the will of the voter. In Chapters 4, 5, 6, and 7, the committee provides its analyses of the challenges faced by the nation in achieving accurate elections and offers its recommendations to address these challenges.