4

Analysis of Components of Elections

In this chapter, the committee examines and provides recommendations regarding key components of U.S. elections. The topics discussed are voter registration and voter registration lists, absentee voting, pollbooks, ballot design, voting technology, and voting system certification. Weaknesses in any component can undermine the integrity of elections.

VOTER REGISTRATION AND VOTER REGISTRATION LISTS

Overview and Analysis

Federal and state laws and regulations govern voter eligibility. Federal law, for instance, stipulates that U.S. citizens of at least 18 years of age be entitled to vote in federal elections. State laws require that a voter be a resident (in some cases, resident for some minimum period of time, such as 30 days) of the state. Some states limit voter eligibility on the basis of criminal status or mental competency, although the specifics of such limitations vary. Some communities allow part-time residents who would otherwise be ineligible to vote to cast ballots in local election contests.

Constitutional provisions and federal statutes regulate how states administer voter registration. Since the 1960s, Congress has gradually expanded federal oversight of election administration and registration provisions. The Voting Rights Act (VRA) of 1965 prohibits discriminatory voting practices and prevents an individual from being denied the right to vote because of errors or omissions on registration materials that are not material to determining the voter’s qualification to vote. Subsequent legislation

aimed at facilitating voter registration includes the Voting Accessibility for the Elderly and Handicapped Act (VAEHA) of 1984 and the Uniformed and Overseas Citizen Absentee Voting Act (UOCAVA) of 1986. The National Voter Registration Act (NVRA) of 1993 requires that applications be made available at a variety of public locations and by mail and establishes broad guidelines concerning the maintenance of voter registration lists.1

The 2002 Help America Vote Act (HAVA) requires states to move from locally administered registration lists to state-level centralized, computerized voter registration lists. These state lists act as the official record of eligible voters for federal elections. HAVA requires regular maintenance of the lists for accuracy and completeness and stipulates that state or local officials should provide “adequate technological security measures to prevent the unauthorized access to the computerized” voter registration list.2 The Act requires that a unique identifier be assigned to each legally registered voter in the state’s voter registration list.3 It states that applications for voter registration may not be accepted or processed by states without either a driver’s license number, the last four digits of the applicant’s Social Security number, or state-issued identification4 and requires that those who register by mail present identifying information at the polls on Election Day the first time they vote (or with their mail-in ballots if voting by mail).5

An applicant’s original signature on a voter registration form constitutes certification that the information provided is true, may be used to authenticate the identity of a voter if there are changes in the registrant’s voting status, and often provides a means for authenticating the identity of the voter at a polling place or when processing absentee and/or mailed ballots.

If a voter registers to vote at a department of motor vehicles (DMV), relevant personal information may be provided at the DMV or extracted from the information in DMV files. This information is then transmitted electronically to the relevant election office with a copy of the signature

___________________

1 Voting Accessibility for Elderly and Handicapped Act, 52 U.S.C. §§ 20101 et seq.; Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act, 52 U.S.C. §§ 20301 et seq.; National Voter Registration Act, 52 U.S.C. §§ 20501 et seq.

2 HAVA, § 303.a.3, 52 U.S.C. § 21083. The Act does not specify what measures should be employed.

3 HAVA, § 303.a.1.A, 52 U.S.C. § 21083.

4 HAVA, § 303.a.5.A.i.I-II, 52 U.S.C. § 21083. “If an applicant for voter registration for an election for Federal office has not been issued a current and valid driver’s license or a Social Security number, the State shall assign the applicant a number which will serve to identify the applicant for voter registration purposes. To the extent that the State has a computerized list in effect under this subsection and the list assigns unique identifying numbers to registrants, the number assigned under this clause shall be the unique identifying number assigned under the list (see Section 303.a.5.A.ii).

5 HAVA, § 303.b.2.A.i.I-II, 52 U.S.C. § 21083.

on file with the DMV. When voters register entirely online, original signatures on file with DMVs or other agencies may be used for authentication purposes.

In those jurisdictions using the most common form of automatic voter registration, when an individual registers for a driver’s license, information is shared with the state elections agency, where eligibility is established and, if eligible, the individual is registered to vote.6 States have adopted various methods for individuals to opt out of registration, ranging from opting-out at the DMV to being notified of procedures to opt-out via a post card.7

Before adding individuals to a voter registration list, an attempt must be made to verify the information provided on a first-time voter registration application against the relevant state’s department of motor vehicles database of driver’s license numbers or the Social Security Administration’s (SSA’s) database of Social Security numbers. For a non-match, election administrators in most states will attempt to contact the applicant so that he or she can provide additional information. HAVA requires that an applicant who cannot be matched to a database be allowed to cast a provisional ballot on Election Day “upon the execution of a written affirmation by the individual . . . stating that the individual is . . . a registered voter in the jurisdiction in which the individual desires to vote; and” is “eligible to vote in that election.”8

Federal law also requires states to establish a program “that makes a reasonable effort to remove the names of ineligible voters” from official voter registration lists.9 States may use information supplied by the U.S. Postal Service (USPS) to identify registrants whose address may have changed.10 To identify voters who have moved, election administrators often send periodic mailings to all voters in the jurisdiction or consult third-party move data. The envelope indicates that the mailing should not be forwarded and should be returned to the sender. Notices that are returned to the election official are an indication that the voter may have moved.

The databases containing voter registration lists often are connected, directly or indirectly, to the Internet or state computer networks. This connectivity raises concerns about unauthorized access to or manipulation of the registrant list or disruption of the registration system. Incidents of external intrusions have been reported recently:

___________________

6 Some states have expanded the set of state agencies that can contribute new voters to the rolls, such as social service agencies and Alaska’s Permanent Fund Dividend agency. DMV databases are known to be unreliable.

7 See National Conference of State Legislatures, “Automatic Voter Registration,” available at: http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/automatic-voter-registration.aspx.

8 See HAVA § 302.a, 52 U.S.C. § 21083.

9 National Voter Registration Act of 1993 (NVRA) § 8.a.4, 52 U.S.C. §§ 20501–20511.

10 NVRA, § 8.c.A, 52 U.S.C. §§ 20501–20511.

- In Illinois, Russian actors targeted and breached an online voter database in 2016 by exploiting a coding error.11 For 3 weeks, they maintained undetected access to the system. Ultimately, personal information was obtained on more than 90,000 voters.12

- In California, hackers penetrated state registration databases and gained access to the personal information of a large number of voters.13

- In Georgia, more than 6.5 million voter records and other privileged information were exposed due to a server error. The security vulnerability had not been addressed 6 months after it was first reported to authorities, even though it could have been used to manipulate the state’s election system.14

Election administrators usually rely on county or state government information technology (IT) departments to secure voter registration databases. In many cases, voter registration offices and election offices are separate departments in county government. In some cases, such as was the case in the Georgia example above, election data may be housed and managed in non-election offices.

Voter registration lists are used for many purposes other than establishing the eligibility of an individual to vote in an election. Voter registration lists are used, for example, by candidates and political parties to identify and contact potential voters.15 At the local level, they are used to estimate how many people will vote, which helps guide election administrators as they prepare polling places for Election Day. These lists also are used in

___________________

11 See Edwards, Brad, “Russian Hack into Illinois Election Database Was Worse Than Thought,” CBS Chicago, June 13, 2017, available at: http://chicago.cbslocal.com/2017/06/13/russian-hack-into-illinois-election-database-worse-than-thought/; “Illinois Elections Board Offers More Information on Hacking Incident,” WSIU, May 4, 2017, available at: http://news.wsiu.org/post/illinois-elections-board-offers-more-information-hacking-incident#stream/0; and Uchill, Joe, “Illinois Voting Records Hack Didn’t Target Specific Records, Says IT Staff,” The Hill, May 4, 2017, available at: http://thehill.com/policy/cybersecurity/331981-ill-voting-records-hack-didnt-target-specific-records-says-state-it.

12 “Illinois Elections Board Offers More Information on Hacking Incident.”

13 See Reilly, Katie, “Russians Hacked Arizona Voter Registration Database—Official,” Time, August 30, 2016, available at: http://time.com/4472169/russian-hackers-arizona-voterregistration/ and Uchill, Joe, “Hackers Demand Ransom for California Voter Database,” The Hill, December 15, 2017, available at: http://thehill.com/policy/cybersecurity/365113-hackers-demand-ransom-for-california-voter-database.

14 See Bajak, Frank, “APNewsBreak: Georgia Election Server Wiped After Suit Filed,” Associated Press, October 27, 2017, available at: https://www.apnews.com/877ee1015f1c43f1965f63538b035d3f.

15 See Hersh, Eitan, Hacking the Electorate: How Campaigns Perceive Voters (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015).

some jurisdictions to establish signature and vote thresholds for petitions and referenda and to select jury pools.

Ideally, voter registration lists should include all eligible individuals who wish to be registered and no ineligible individuals. Voter registration lists should, therefore, be both accurate and complete. In this case, the term “accurate” can refer either to the factual correctness of the data that exist in the database or to the notion that the database contains none of the individuals not eligible to vote. The term “complete” refers to the presence in the database of all eligible individuals who wish to be registered.16

Maintenance of a voter registration list requires maintaining the currency of the registrant list and removing duplicate registrations and ineligible voters. This task requires comparing records within a voter registration list to other records to identify duplicate registrations (which are usually associated with changes of address or name) and comparing voter registration lists to other official lists that contain information about individuals who are ineligible to vote in a state, typically felons and individuals declared mentally incompetent.17 Voter lists, of course, must be regularly compared against death registries. Data matching can draw either on intrastate sources, such as social service, motor vehicle, and death records or on interstate sources, such as the cross-state record matching performed by organizations such as the Electronic Registration Information Center (ERIC) and the Interstate Voter Registration Crosscheck System.18,19,20 HAVA provides some criteria for developing and maintaining voter registration databases, and the U.S. Election Assistance Commission (EAC)

___________________

16 See National Research Council, Improving State Voter Registration Databases: Final Report, (Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2010), available at: https://doi.org/10.17226/12788, p. 2.

17 Ibid, p. 1.

18 Data matching systems are imperfect. They can—and do—generate false matches that could potentially lead to the disenfranchisement of legitimate voters.

19 ERIC “is a non-profit organization with the sole mission of assisting states to improve the accuracy of America’s voter rolls and increase access to voter registration for all eligible citizens” (see http://www.ericstates.org/). As of the writing of this report, 22 states and the District of Columbia are members of ERIC. The 22 states are Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Louisiana, Illinois, Maryland, Minnesota, Missouri, Nevada, New Mexico, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Utah, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, and Wisconsin. See http://www.ericstates.org/faq.

20 The Interstate Voter Registration Crosscheck System is operated by the office of the Secretary of State of the state of Kansas. The system compares voter rolls in participating states to identify potential duplicate voter registrations. It identifies voter registrations that have identical first names, last names, and dates of birth. According to the office of the Kansas Secretary of State, 28 states participated in Crosscheck in 2017. See http://www.wbur.org/radioboston/2017/11/03/massachusetts-crosscheck-system.

The system recently halted operations due to accuracy and security concerns raised by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

has issued guidance, but states maintain a degree of discretion in how to conform to these requirements.21

States have taken different approaches to building systems to meet the federal requirement for centralized voter registration lists. Under the so-called “top-down” approach followed by many states, state election administrators maintain a single, unified database and local election administrators provide the state with updates for the information needed in the database. Some states have instead opted for a bottom-up approach. In this scenario, local jurisdictions maintain their own registration lists but provide periodic updates to a separate statewide system. Other states use a hybrid approach that combines elements of both the top-down and bottom-up approaches.

The EAC’s “2016 Statutory Overview” found that 38 states have voter registration databases that use a top-down approach, 9 have a hybrid system where counties manage their voter registration databases either through direct use of the state’s database or independently using a third-party vendor (in the latter case, data is uploaded nightly to the state database), and 6 states employ a bottom-up approach.22

The USPS does not automatically notify election administrators of an individual’s change of address. Election administrators must initiate address checks with USPS on their own. States may also obtain information on changes of address from departments of motor vehicles or other state agencies.

Two recent court decisions have significant implications for voter registration. In Fish v. Kobach, voters sued Kansas Secretary of State Kris Kobach for enforcing a state law that required Kansans to provide proof-of-citizenship documents in order to register to vote.23 On June 18, 2018, the United States District Court for the District of Kansas found the law to be unconstitutional, because it created an unnecessary burden on voters. In Husted v. A. Philip Randolph Institute, the U.S. Supreme Court on June 11, 2018 upheld an Ohio law that allows the state to strike voters from the registration rolls if they fail to return a mailed address confirmation form and then do not vote for 4 years or two federal election cycles.24 Lower courts had ruled that the law violated the National Voter Registration Act, which states that individuals may not be purged from the voter rolls because of a

___________________

21 See HAVA, Section 303 and U.S. Election Assistance Commission, “Checklist for Securing Voter Registration Data,” October 23, 2017, available at: https://www.eac.gov/documents/2017/10/23/checklist-for-securing-voter-registration-data/.

22 See Green, Seth, “Statewide Voter Registration Systems,” August 31, 2017, available at: https://www.eac.gov/statewide-voter-registration-systems/. A table that shows the approach employed by each state is available at this site.

23Fish v. Kobach, 2:16-cv-02105-JAR (D. Kan. 2018).

24Husted v. A. Philip Randolph Institute, 584 U.S. ___ (2018).

failure to vote. The Supreme Court concluded that the Ohio law does not deregister voters solely because of a failure to vote, but does so in conjunction with a failure to return an address confirmation form.

States have adopted numerous methods to facilitate voter registration: in person; by mail or fax; Internet; automatic registration; same-day registration. Each have advantages and disadvantages. Automatic voter registration may improve voter participation, reduce costs, and increase the accuracy of voter rolls. It may, however, needlessly register individuals who do not care to be registered, and if the systems are not well designed, it may be possible for noncitizens to end up on the voter rolls.25 With regard to online registration, cost savings and voter convenience may be benefits. Security risks are, however, an inherent part of any online system.26 For same-day registration, additional costs may be associated with system implementation (e.g., necessity to purchase additional equipment like e-pollbooks or ballot-on demand printers; costs of network connectivity; costs of updating voter registration systems to accommodate same-day registration, etc.). Some have suggested that same-day registration may increase voter turnout.27

Voter rolls inherently contain inaccuracies. Database maintenance is critical, but cannot yield perfect accuracy or completeness. It can be difficult to maintain the accuracy of voter registration lists due to changes in address, name, or life status. Sophisticated tools used in other industries may provide better record matching.28 ERIC is one organization that attempts to make high-quality industry matching tools available to state election officials, but the existence of ERIC does not preclude states from exploring other record matching tools.

Electronic voter registration databases, like all electronic systems, are vulnerable to cyberattacks. If the contents of a voter registration database are altered or connectivity to a voter registration database is interrupted on Election Day either because of connectivity issues or because of efforts by external actors (e.g., by a denial-of-service attack), the consequences for voter convenience, voter confidence, and elections outcomes could be

___________________

25 See http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/automatic-voter-registration.aspx.

26 See http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/electronic-or-online-voter-registration.aspx.

27 See http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/same-day-registration.aspx.

28 For example: techniques for record linkage; the use of preprocessing to standardize data elements; accounting for the relative frequency of occurrence of values of strings such as first and last names; estimation of optimal matching parameters; and providing methods for estimating false match rates. See National Research Council, Improving State Voter Registration Databases: Final Report (Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2010), pp. 72-73, available at: https://doi.org/10.17226/12788.

very serious, especially if network-connected e-pollbooks are used and no backup of a voter registration list is available. Even if a voter registration database is not altered, the theft of the information contained in voter registration databases could cause serious problems. Driver’s license numbers and Social Security numbers, for example, could be used for identity theft or for the purpose of requesting absentee ballots.29 Attacks that alter voter registration data could be used to introduce fake or illegitimate voters, to remove valid voters from voter registration databases, or to force provisional voting on Election Day. The latter would likely be detected but could, nevertheless, cause long lines and other disruptions at polling sites. If an attacker targeted voters in jurisdictions that tend to favor one political party, such an attack could have a partisan effect on election results.

Even when a registration database is reasonably protected, online portals that allow voters to update their registration information can provide a point of entry for the alteration of data. Update requests often require weak authentication. In some states, the information required to change a registration is available from public records.

Findings

Simple voter registration methods encourage voter participation. Cumbersome voting registration systems may disenfranchise voters.

Voter registration databases face accuracy and completeness requirements that are in tension with one another. Measures to increase accuracy (e.g., purging suspect data) may reduce completeness. Measures to increase completeness (e.g., not purging suspect data) may reduce accuracy.

Electronic voter registration systems may make it easier to manage and maintain voter registration databases. The use of electronic information from other government sources may increase the accuracy and completeness of the databases.

Electronic voter databases are subject to cybersecurity vulnerabilities and attacks.

Election officials may not have the authority to request or insist on cybersecurity protections for voter registration databases or the resources to pay for appropriate cybersecurity measures.

Voter records contain personally identifiable information that, if compromised, could be used to the detriment of voters outside of the election context.

___________________

29 Only a small number of states are permitted to collect Social Security numbers for voter registration purposes, although all states can collect the last four digits of Social Security numbers.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- 4.1 Election administrators should routinely assess the integrity of voter registration databases and the integrity of voter registration databases connected to other applications. They should develop plans that detail security procedures for assessing voter registration database integrity and put in place systems that detect efforts to probe, tamper with, or interfere with voter registration systems. States should require election administrators to report any detected compromises or vulnerabilities in voter registration systems to the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, the U.S. Election Assistance Commission, and state officials.

- 4.2 Vendors should be required to report to their customers, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, the U.S. Election Assistance Commission, and state officials any detected efforts to probe, tamper with, or interfere with voter registration systems.

- 4.3 All states should participate in a system of cross-state matching of voter registrations, such as the Electronic Registration Information Center (ERIC). States must ensure that, in the utilization of cross-matching voter databases, eligible voters are not removed from voter rolls.

- 4.4 Organizations engaged in managing and cross-matching voter information should continue to improve security and privacy practices. These organizations should be subject to external audits to ensure compliance with best security practices.

VOTING BY MAIL, INCLUDING ABSENTEE VOTING

Overview and Analysis

Absentee voting (voting remotely) provides an opportunity to cast a vote by obtaining a ballot (usually a printed ballot obtained by mail) in advance of an election and returning the completed ballot to elections officials by mail30 or other means. If paper ballots are used, voters typically mark the received ballot and place it in a secrecy envelope or sleeve. The envelope/sleeve is then placed into a second mailing envelope. The voter seals the mailing envelope and signs an affidavit on the envelope’s exterior. The ballot is then mailed to the appropriate elections office or deposited at a designated dropoff location.31 To be counted, absentee ballots must be postmarked, deposited, or received by a deadline that is generally estab-

___________________

30 In at least 22 states, certain elections may be conducted entirely by mail. See http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/all-mail-elections.aspx.

31 See http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/all-mail-elections.aspx.

lished by state governments. In many jurisdictions, the identity of the voter is confirmed by matching the signature on the envelope against the signature in the voter registration database.32

As discussed in Chapter 3, three states, Washington, Oregon, and Colorado principally use the mails to distribute ballots to all registered voters, and two others, California and Utah, are moving toward this model.33 In these instances, ballots are mailed to all registered voters. Other “states permit all-mail elections in certain circumstances, such as special districts, municipal elections, when candidates are unopposed, or at the discretion of the county clerk.”34

In some jurisdictions, signature matching is completed automatically by a computer that compares the signature on a scanned paper ballot to signatures on file in a database. In other jurisdictions, a non-expert election administrator compares signatures. Both methods can result in mismatching. In addition, an individual’s signature may change over time. If a signature database is not updated regularly, mismatching may occur. Inaccurate matching may result in the rejection of valid ballots.

Ninety-nine percent of absentee ballots categorized as “returned and submitted for counting” were ultimately counted in the 2016 federal election.35 In 2016, the most common reasons that absentee ballots were rejected were that the signature on the ballot did not match the signature in a state’s records, that the required signature was missing, or that the ballot was received after deadline.36

UOCAVA allows “U.S. citizens who are active members of the Uniformed Services, the Merchant Marine, and the commissioned corps of the Public Health Service and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, their eligible family members and U.S. citizens residing outside

___________________

32 Some states accommodate remote accessible ballot marking. In such states, a voter retrieves and marks a ballot online, prints out the completed ballot, and mails the ballot to the appropriate elections office. See, e.g., https://nfb.org/ohio-requires-accessible-absentee-ballots-blind; https://www.sos.state.oh.us/globalassets/elections/directives/2018/dir2018-03.pdf; https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201520160AB2252; and http://sfgov.org/elections/remote-accessible-vote-mail-system.

33 Masterson, Matthew, U.S. Election Assistance Commission, presentation to the committee, April 5, 2017, Washington, DC. See also “2016 Election Administration and Voting Survey” (EAVS), p. 9.

In Washington, every county has at least one vote center for in-person voting (see https://www.sos.wa.gov/elections/faq_vote_by_mail.aspx). In Oregon, each county elections office provides privacy booths for voters who want to vote in person or voters who need assistance (see https://multco.us/file/31968/download). In Colorado, voters have the option to vote in person at a county Voter Service and Polling Center (VSPC) (see https://www.sos.state.co.us/pubs/elections/FAQs/ElectionDay.html).

34 See http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/all-mail-elections.aspx.

35 “2016 Election Administration and Voting Survey” (EAVS), p. 10.

36 Ibid.

the United States” to vote using absentee ballots.37 UOCAVA voters must have a legal voting residence in the jurisdiction where they want to vote.38 The USPS and the Military Postal Service Agency (MPSA) have special procedures for handling UOCAVA outgoing and incoming ballots.39

In 2009, Congress amended portions of UOCAVA with the Military and Oversees Voter Empowerment Act (MOVE). MOVE stipulates that ballots requested by UOCAVA voters must be transmitted 45 days before a federal election, that voters have the right to receive their ballots by at least one electronic method (email, online, or fax) or by mail, and that states must have a system in place to determine whether a ballot was received by the appropriate elections office.40

To be counted, UOCAVA ballots must be returned to the appropriate election office before a state-mandated deadline.41 In 2016, states reported transmitting 930,156 UOCAVA ballots. Of this number, 633,592 were returned.42 Approximately 110,000 more ballots were transmitted to overseas citizens than to uniformed services voters.43 Of the UOCAVA ballots returned by voters, 512,696 (80.9 percent) were counted.44

Absentee voting introduces benefits and risks that are different from the benefits and risks of in-person voting.45 By-mail voting increases convenience, especially for the disabled community, and may improve the amount of thought that goes into marking a ballot. A common justification for voting by mail is increasing the amount of deliberation voters give to their ballots. However, the evidence presented to support this claim tends to be anecdotal or based on appeals to logic. There appears to be no peer-reviewed empirical research to quantify the degree to which increased voter knowledge or deliberation is associated with expanding mail-ballot opportunities. There is evidence, though, that the convenience of by-mail voting

___________________

37 See https://www.fvap.gov/info/laws/uocava.

38 See U.S. Election Assistance Commission, “Tips for Helping UOCAVA Voters and their Families,” p. 3, available at: https://www.eac.gov/documents/2017/08/03/six-tips-for-helping-uocava-voters-and-their-families-from-eac-contingency-plan-election-administration-pre-election-security/.

39 Ibid, p. 6.

40 Ibid, p. 2.

41 Ibid, p. 12.

42 Ibid.

43 Ibid, p. 11.

44 Ibid, p. 12.

45 Stewart, Charles III, “Losing Votes by Mail,” New York University Journal of Legislation and Public Policy 13, 2010, No. 3, pp. 573-601. Dr. Stewart is a member of the committee that authored the current report.

may stimulate increased voter turnout in certain situations.46 There are other indications, however, that by-mail voting may initially increase voter turnout rates but that rates then revert to previous turnout patterns and that by-mail voting can depress turnout in presidential and gubernatorial general elections.47 Further, all-mail voting may produce a cost savings.48 For instance, in a study of Colorado’s 2013 mandate that mail ballots be sent to all registered voters, the Pew Charitable Trusts estimated that this reform decreased costs by an average of 40 percent, in addition to reducing the use of provisional ballots by 98 percent.49

Remote voting creates new opportunities for coercion and for loss of privacy that in-person voting attempts to overcome.50 Outside of the privacy of a voting booth, other individuals may buy or sell votes or overtly pressure a voter to make particular ballot selections. Ballots may be stolen or intercepted by third parties who mark and cast them. It may also be easier for an election administrator to examine a ballot before it is separated from its identifying outer envelope or email header. In the case of all-mail voting, the dependence on written instructions rather than poll-worker assistance may disadvantage some voters and increase the residual vote rate.51

The paths that mail ballots travel introduce other risks that are typically avoided with in-person voting. Most absentee and mail balloting relies on the U.S. postal system to (1) deliver the request for an absentee ballot from the voter to the local jurisdiction; (2) deliver the unmarked ballot from

___________________

46 See Gerber, Alan S., Gregory A. Huber, and Seth J. Hill, “Identifying the Effect of All-mail Elections on Turnout: Staggered Reform in the Evergreen State,” Political Science Research and Methods, 2013, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 91-116; Miller, Peter and Sierra Powell, “Overcoming Voting Obstacles: The Use of Convenience Voting by Voters with Disabilities,” American Politics Research, 2016, Vol 44, No. 1, pp. 28-55; and Flaxman, Seth, Marie-Fatima Hyacinthe, Parker Lawson, and Kathryn Peters,” Voting by Mail: Increasing the Use and Reliability of Mail-Based Voting Options,” available at: http://web.mit.edu/supportthevoter/www/files/2013/11/Vote-by-Mail-Reform-Memo.pdf.

47 See, e.g., https://www.eac.gov/documents/2017/02/23/will-vote-by-mail-elections-increase-turnout/.

48 See “Voting by Mail: Increasing the Use and Reliability of Mail-Based Voting Options.”

49 Pew Charitable Trusts, “Colorado Voting Reforms: Early Results,” available at: http://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2016/03/coloradovotingreformsearlyresults.pdf.

50 See http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/all-mail-elections.aspx.

51 Alvarez, R. Michael, Dustin Beckett, and Charles Stewart III, “Voting Technology, Vote-by-Mail, and Residual Votes in California, 1990–2010,” Political Research Quarterly, 2013, Vol. 66, No. 3, pp. 658-670.

“Residual votes” are the sum of over- and under-votes on a ballot, typically measured at the top of the ticket. See Stewart, Charles III, “Voting Technologies,” Annual Review of Political Science, 2011, Vol. 14, pp. 353-378. Dr. Stewart is a member of the committee that authored the current report.

the jurisdiction back to the voter; and (3) deliver the marked ballot back to the election jurisdiction for counting.

The marked ballot is a more valuable target than a request for a mail ballot or even the unmarked ballot. The secrecy associated with marked ballots makes it more difficult for a voter to detect whether a marked ballot has been tampered with or intercepted.

The heavy reliance on the U.S. postal system for mail ballots introduces potential problems related to inconsistencies in service. “Mail delivery is not uniform across the nation. Native Americans on reservations may in particular have difficulty. Many do not have street addresses, and their P.O. boxes may be shared.”52 The mail return of marked ballots may be delayed past the deadline. Since, currently, there are no agreed upon chain-of-custody procedures for mailed ballots, mail-in voting presents more chances for votes to be lost than is the case with in-person voting. Collection points for mail-in ballots reduce dependence on the postal system and provide voters with greater assurance that their ballots will be received.53

Because of concerns about the chain-of-custody of mail ballots, local election officials—often in direct cooperation with the USPS—have adopted practices to allow officials and voters to track the location of mail ballots through the mail stream.54 These systems allow postal mail to be tracked via the USPS’s Intelligent Mail Barcode. There are services available to election officials to facilitate the use of this data, including products like Ballot Scout, Ballot Tracks, and Ballot Trace.55

Concerns over the speed and reliability of the USPS have led to the replacement of the mails with electronic means, particularly the Internet, in the administration of voting by mail in many jurisdictions. While there are administrative gains to be had by moving to the electronic transmission of absentee ballot requests, and the transmission of unmarked ballots to voters, this practice comes with many of the cybersecurity vulnerabilities discussed in Chapter 5 of this report. However, because there are also vulnerabilities with using the mails to request absentee ballots and transmit unmarked ballots to voters, it may be that relying on the Internet for these portions of the vote-by-mail system could lead to a net improvement

___________________

52 See http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/all-mail-elections.aspx.

53 Stewart, Charles III, “Losing Votes by Mail,” Journal of Legislation and Public Policy, Vol. 13, No. 3, pp. 573-601. Dr. Stewart is a member of the committee that authored the current report.

54 Bipartisan Policy Center, “The New Realities of Voting by Mail in 2016,” June 2016, available at: https://bipartisanpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/BPC-Voting-By-Mail.pdf.

55 In the 2014 federal election, 35 states had tools on their state election websites that allowed voters to track their absentee ballots. See Pew Charitable Trusts, “Elections Performance Index,” available at: http://www.pewtrusts.org/en/multimedia/data-visualizations/2014/elections-performance-index#indicatorProfile-OLT.

in the administration of mail-balloting. However, it appears that no peer-reviewed research has comprehensively assessed the relative risk-reward tradeoffs involved in using the mails to transmit absentee ballot requests and unmarked ballots.

Few marked ballots are currently transmitted electronically. The electronic transmission of absentee ballots—via fax, email, or web portal—is most often reserved for voters who fall under UOCAVA “as these voters often face unique challenges in obtaining and returning absentee ballots within state deadlines.”56 Three states, Arizona, Missouri, and North Dakota, allow some voters to return marked ballots using a web-based portal, but Missouri only offers electronic ballot return for military voters serving in a “hostile zone.”57 In North Dakota and Arizona, any UOCAVA voter may use the web option.58 The singular importance of the marked ballot may help explain why few marked ballots are currently transmitted electronically.

Findings

Vote-by-mail may increase convenience and satisfaction, as voters may complete ballots from the comfort of their home and devote as much time as they wish to assess candidates and issues.

Vote-by-mail can make voting more accessible for individuals with disabilities.

___________________

56 See http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/Internet-voting.aspx.

57 “Alabama conducted a pilot project in 2016 to permit UOCAVA voters located outside of U.S. territorial limits to submit voted ballots via a web portal, but the state has not made this program permanent. Alaska previously made a web portal available to any absentee voter to return a voted ballot, but discontinued this option in 2018.” See http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/Internet-voting.aspx.

The state of Washington allows all voters to return ballots as email attachments—although non-UOCAVA voters must follow up with a physical ballot to have their electronic ballots counted.

The West Virginia Secretary of State has recently announced a pilot to offer voting via mobile devices to military voters. See https://sos.wv.gov/News-Center/Pages/Military-Mobile-Voting-Pilot-Project.aspx.

58 See http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/Internet-voting.aspx.

Twenty-one states (Colorado, Delaware, Hawaii, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Maine, Massachusetts, Mississippi, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, North Carolina, Oregon, South Carolina, Utah, Washington, and West Virginia) and the District of Columbia allow some voters to return ballots via email or fax.

Seven states (Alaska, California, Florida, Louisiana, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, and Texas) allow some voters to return ballots via fax.

Nineteen states (Alabama, Arkansas, Connecticut, Georgia, Illinois, Kentucky, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, Tennessee, Vermont, Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming) do not allow electronic return of ballots. Voters must return voted ballots via postal mail. See http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/Internet-voting.aspx.

Vote-by-mail may produce cost savings.

Vote-by mail requires careful design of ballot transmittal envelopes and tabulation procedures.

With vote-by-mail, it is not possible to guarantee that a voter has cast his or her ballot privately. A voter might be coerced into making particular selections.

Currently, there are no agreed upon chain-of-custody procedures for mailed ballots. Vote-by-mail presents more chances for votes to be lost than is the case with in-person voting.

Drop boxes for mail-in ballots outside of elections offices reduce dependence on the postal system.

Collection points for mail-in ballots introduce additional points of failure and security concerns.

Election jurisdictions are increasingly adopting programs that allow officials and voters to track the location of mail ballots.

All-mail elections may slow down the vote counting process, especially if ballots are accepted according to postmark date (and thus may be received and counted days or weeks after the election).

UOCAVA voting presents unique challenges for election administration with regard to the transmission of ballots to and from remote locations.

RECOMMENDATION

- 4.5 All voting jurisdictions should provide means for a voter to easily check whether a ballot sent by mail has been dispatched to him or her and, subsequently, whether his or her marked ballot has been received and accepted by the appropriate elections officials.

POLLBOOKS

Overview and Analysis

When a voter arrives at a polling place, the voter typically “checks in” to vote by providing a name and/or some form of identification to a poll worker, who matches the given name to information in a pollbook.59 In some states, voters may be required to fulfill a non-documentary identification requirement. In lieu of presenting a document that establishes their identity, they might, for instance, be required to sign an affidavit asserting eligibility to vote, provide a signature, or provide personal information either orally or in writing. Once an individual’s eligibility to vote has been

___________________

59 Thirty-four states have laws requesting or requiring voters to show some sort of identification at the polls. See http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/voter-id.aspx.

determined, an eligible voter may proceed to cast a vote. If an individual’s eligibility cannot be confirmed, that individual must be offered the opportunity to cast a provisional ballot. The procedures for when to issue and count provisional ballots are established by individual states.60

While most jurisdictions (81.8 percent) still use preprinted paper registration lists to check in voters, between the 2012 to 2016 federal elections, there was a 75 percent increase in the use of electronic pollbooks (e-pollbooks) where paper is replaced by computers either containing locally stored lists of registered voters or connected to digital voter registration databases via the Internet. In the 2016 election, at least 1,146 jurisdictions (17.7 percent of all jurisdictions) used e-pollbooks.61 Because larger jurisdictions tend to use e-pollbooks, the fraction of voters checked-in using e-pollbooks is close to 50 percent.62

E-pollbooks provide more data to poll workers than traditional paper pollbooks. E-pollbooks may be networked and receive immediate updates on who has voted in other voting locations. They may allow poll workers to look up voters from an entire county or state or notify a poll worker that a voter has already voted.63 A poll worker may use an e-pollbook to direct a voter to the correct polling location. E-pollbooks may also host on-demand training tips and procedural guides for poll workers. “Some e-pollbooks can scan driver’s licenses, speeding up the voter check-in process. Other e-pollbooks use an electronic signature pad that immediately captures the voter’s signature.”64 E-pollbooks may also produce turnout numbers and lists of those who voted.65

The requirements for the certification of e-pollbooks vary considerably among the states and jurisdictions that permit their use.66 As of March 2017, only eight states certify e-pollbooks. Eleven states have statutes

___________________

60 See Appendix E.

61 “2016 Election Administration and Voting Survey” (EAVS), p. 8.

62 This figure was calculated directly from the Election Administration and Voting Survey dataset available on the website of the U.S. Election Assistance Commission at https://www.eac.gov/research-and-data/election-administration-voting-survey/.

63 With regard to absentee ballots, standard practice is to check voter registration systems to see whether the voter is recorded as having already voted. If an individual has returned an absentee ballot prior to Election Day, this information should be reflected in the poll book (whether it is electronic or not). If the absentee ballot arrives after Election Day and the voter cast a ballot on Election Day, the absentee ballot should be reflected in the voter registration system. The issue of multiple voting is most critical in jurisdictions with multiple vote centers. In this instance, it is important that e-pollbooks be updated in real time.

64 See Hubler, Katie Owens, “All About E-Poll Books,” NCSL’s The Canvass, Issue 46, February 2014, available at: http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/the-canvass-february-2014.aspx#Poll%20Books.

65 Ibid.

66 In general, to achieve certification, a system must undergo independent testing to verify that it meets specified requirements for design and performance.

explicitly authorizing the use of e-pollbooks, three states have statutes referring to e-pollbooks without explicitly authorizing their use, five states have established procedures or certification requirements dictated by the state but not by statute, and three states have jurisdictions that used e-pollbooks absent mention in statute or rule.67

While attacks on e-pollbooks could be used to change voter data, prevent access to voter registration data, fool the devices’ check-in logic to allow multiple voting by individuals, or access back-end systems, there are no national security standards for e-pollbooks.68 As a result, security practices vary across states. Some states conduct testing before each election, some make backup e-pollbooks available on Election Day, and some make backup paper rolls available on Election Day. Others leave testing or audits up to individual counties or provide no backup system.69

The static nature of printed pollbooks presents several problems, because voter registration recruitment continues until the registration deadline.70 Voter registration offices may not be able to finish entering registrant data into voter registration databases before pollbooks must be printed for distribution to polling places. In light of this, some voter registration offices create supplemental lists for distribution to election judges immediately prior to an election. The success of this approach depends on numerous logistical factors (e.g., timely delivery).

Paper pollbooks may present a risk in the context of convenience programs like vote centers and early voting, as the use of paper pollbooks would not prevent a voter from casting a ballot in more than one location. In such scenarios, multiple voting may only become apparent after the fact, and documentation may not be enough for successful prosecution. While voter registration offices may be contacted to qualify each voter, voter registration call centers have limited capacity, and cell phone service at polling places may not be reliable.

Provided that they are properly counted, the use of provisional ballots offers a potential solution to a compromised e-pollbook system. However, if an e-pollbook system were compromised to the point that a jurisdiction had to rely solely on provisional ballots, it is likely that the delays produced by the provisional ballot procedure, and the attending chaos at

___________________

67 See http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/electronic-pollbooks.aspx.

68 See Norden, Lawrence and Ian Vandewalker, Brennan Center for Justice, “Securing Elections from Foreign Interference,” 2017, available at: https://www.brennancenter.org/sites/default/files/publications/Securing_Elections_From_Foreign_Interference_1.pdf.

69 See Pew Charitable Trust, “A Look at How—and How Many—States Adopt Electronic Poll Books,” available at: http://www.pewtrusts.org/en/multimedia/data-visualizations/2017/a-look-at-how-and-how-many-states-adopt-electronic-poll-books.

70 The move in many jurisdictions to same-day registration means that the contents of pollbooks may be in flux even on Election Day.

the polls, would produce significant problems with voter confidence—and perhaps disenfranchise voters. Nonetheless, if paper poll books are used in emergencies, it will be possible to determine the number of illegal multiple votes after the election ends. This acts not only as a deterrent to unlawful voting but as a mechanism for determining whether illegal votes may have changed the outcome of an election.

The move in many jurisdictions to same-day registration and early voting makes it necessary to provide distributed access to pollbooks and real-time information on those who are registered to vote or who have voted. This reliance on connectivity presents cybersecurity risks.

E-pollbooks help to ensure that an individual casts only a single ballot as they are able to offer, through online connectivity, access to the most current version of the voter registration database. Voter registration offices can focus on data entry through the early voting period—and even up to Election Day—since data entry need not be completed to meet the cut-off time for the printing and delivery of paper pollbooks.

Findings

Eligible voters may be denied the opportunity to vote a regular ballot if pollbooks are inaccurate.

Internet access to e-pollbooks increases the risks associated with the use of e-pollbooks to manage elections. Cyberattacks can alter the voter registration databases used to generate and update pollbooks. If pollbooks are altered by external actors, eligible citizens might, on election days, be denied the right to vote or ineligible individuals might be permitted to vote. Cyberattacks could also compromise the record of who actually voted on Election Day—or disrupt an election in numerous other ways.

If an e-pollbook is connected to a remote voter registration database and there is no offline backup, a denial-of-service cyberattack could force voting to be halted.

Cybersecurity risks are a factor for consideration when making the decision to use Internet-connected e-pollbooks.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- 4.6 Jurisdictions that use electronic pollbooks should have backup plans in place to provide access to current voter registration lists in the event of any disruption.

- 4.7 Congress should authorize and fund the National Institute of Standards and Technology, in consultation with the U.S. Election Assistance Commission, to develop security standards and verification and validation protocols for electronic pollbooks in

-

addition to the standards and verification and validation protocols they have developed for voting systems.

- 4.8 Election administrators should routinely assess the security of electronic pollbooks against a range of threats such as threats to the integrity, confidentiality, or availability of pollbooks. They should develop plans that detail security procedures for assessing electronic pollbook integrity.

BALLOT DESIGN

Overview and Analysis

The visual presentation of information on ballots has long been a topic of study. With regard to the presentation of information to voters, confidence in the outcome of elections is enhanced when ballots present information clearly and allow voters to make their selections in an intuitive way. Poor ballot design causes confusion and increases the possibility of a cast vote not reflecting the intention of the voter. Poor design may therefore threaten the accuracy of election results, since it may result in votes not cast as intended.

Ballot design requirements are often dictated by state law. Some states legislate the precise language that must be used on a ballot, and sometimes the exact design as well (e.g., layout or font size), making it difficult to update language or improve the functionality of the ballot over time. While there are some benefits to this prescriptive approach, it can hamper the implementation of new technology and introduce confusion for voters.

Ballot designs vary widely and depend on the voting machine or technology in use. Ballots can look different on different machines. Some ballots, like California’s, are typically very long because they may include many statewide offices and initiatives. Initiatives are accompanied by short explanatory text which further extends the length of the ballot.

Poor ballot design can occur when election administrators fail to incorporate proven design principles or are constrained from doing so by voting technology features or local laws and regulations. Problems arise when a typeface is too small, the layout of the ballot is confusing, or the proper place or method to mark the voter’s choice is difficult to discern. Poor ballot design has led to overvoting (inadvertently voting for more than one candidate for the same office), undervoting (failing to vote for any candidate in a contest), and mistaken selections. If, in the latter case, a voter attempts to strike out the erroneous vote and indicate an alternate choice, the ballot may be spoiled.

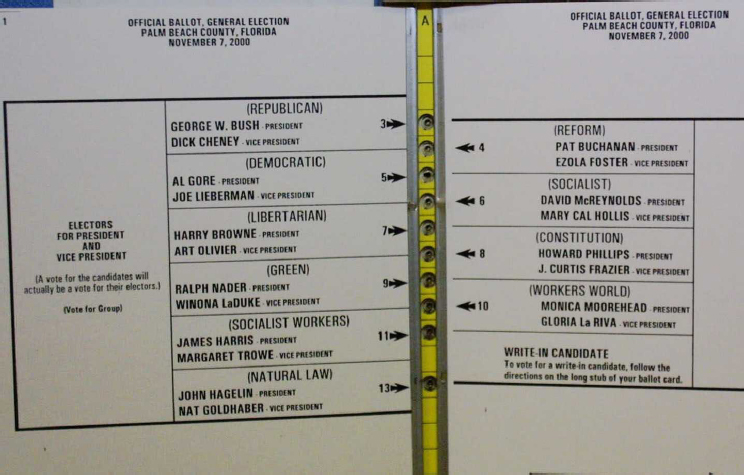

Two well-known examples of poor ballot design originated in Florida. The Palm Beach County “butterfly ballot” (see Figure 4-1) from the 2000

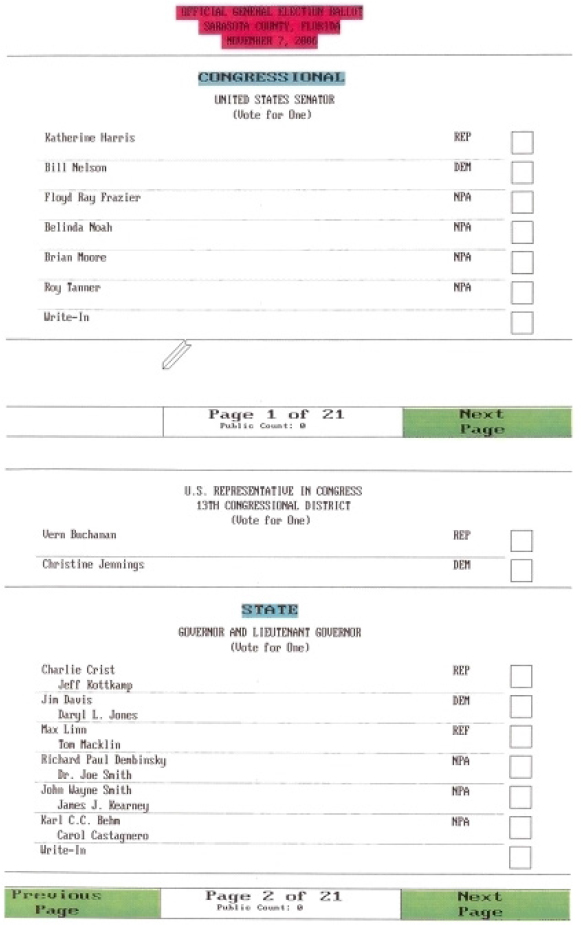

presidential election provides an example of how confusing ballot design can lead to miscast votes. The two-page ballot presented candidate names staggered on alternate sides of a central punch button column. The design directly contributed to an increased number of miscast votes in the election.71 The 2006 general election ballot from Sarasota County illustrates how poor electronic ballot design (see Figure 4-2) may have caused many voters to overlook a congressional race.

SOURCE: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Butterfly_Ballot,_Florida_2000_(large).jpg. Image is ineligible for copyright and therefore in the public domain because it consists entirely of information that is common property and contains no original authorship.

___________________

71 See Wand, Jonathan N., et al., “The Butterfly Did It: The Aberrant Vote for Buchanan in Palm Beach County, Florida,” The American Political Science Review, December 2001, Vol. 95, No. 4, pp. 793-810.

SOURCE: Jefferson, David, “What Happened in Sarasota County?,” The Bridge, 2007, Vol. 37, No. 2, pp. 21-22. Reprinted with permission from Jefferson (2007).

On Election Day, it can be difficult to train voters to cast a vote if procedures are not readily apparent. Votes are cast on machines that may be accessed only briefly every year or two and voters have only minutes to read and mark their ballots. Good ballot design principles are essential when electronic displays are used to present ballots on voting equipment and ballot-marking devices. Studies show that 43 percent of otherwise literate Americans (93 million people) encounter difficulty reading ballot instructions.72 Greater than 60 percent of Americans older than age 65 have physical disabilities that make reading or hearing instructions difficult.73

The use of ballot-marking devices (BMDs) is increasing, as paper ballots present special challenges for disabled voters (see Box 4-1).

Findings

Poor ballot design can significantly affect the ability of voters to understand the choices presented as well as voters’ ability to make selections that reflect their intent.

Poorly designed ballots continue to be used in elections. The embedding of specific ballot design criteria into statutes and regulations makes it difficult to counteract poor design principles.

Ballot design can help voters be successful if it follows proven com-

___________________

72 Quesenbery, Whitney, Center for Civic Design, presentation to the committee, June 13, 2017, New York, NY, citing U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics, National Assessment of Adult Literacy, 2003.

73 Golden, Diane Cordry, Association of Assistive Technology Act Programs, presentation to the committee, June 13, 2017, New York, NY.

munication and display design principles to meet voters’ needs for easy interaction, plain language, consistency, and comprehension.

Good designs for electronically displayed ballots (e.g., designs that foster interaction, facilitate navigation, and incorporate plain language) are positive contributors to the voting experience.

RECOMMENDATION

- 4.9 State requirements for ballot design (inclusive of print, screen, audio, etc.) and testing should use best practices developed by the U.S. Election Assistance Commission and other organizations with expertise in voter usability design (such as the Center for Civic Design).

VOTING TECHNOLOGY

Meeting requirements for cost-effective and accessible voting requires attention to a variety of factors including: (1) accuracy and security; (2) the structure of the election technology market; (3) technology innovation; (4) certification and standards; and (5) the capacity and capability of election administrators to oversee technology acquisition and maintenance.

Many elections today are dependent on electronic voting and vote tabulation systems that collect, store, and process votes. Most voting systems make use of computers and computer networks, but current cybersecurity and auditing requirements have placed increased value on paper even in the context of computerized systems.

As discussed previously, following the 2000 election, through HAVA, Congress provided funding for states to improve election systems. HAVA gave particular attention to statewide voter registration systems and to the procurement of voting systems that would eliminate the problems associated with mechanical lever machines and punch cards in the 2000 presidential election.

Requirements for today’s voting systems include: (1) support for contemporary voting modes and innovative processes such as early voting and vote by mail; (2) usability; (3) accessibility for disabled voters; (4) enhanced cybersecurity; and (5) auditability.

The post-2000 modernization of voting technologies sought to redress deficiencies associated with ballot designs, eliminate punch card systems in which recounts had been plagued by hanging chad, and complete the phase-out of long-obsolete mechanical voting machines.

Jurisdictions that replaced punch card or lever machines generally adopted either optical-scan or Direct Recording Electronic (DRE) voting machines.

DREs generally take the form of a custom computer with a screen to display the ballot. Voters indicate their selections using a touchscreen or a physical keypad. DREs typically employ specialized software running on top of commodity operating systems like Windows or Linux and a mix of standard and custom hardware. In most systems, tabulated votes are recorded in a removable memory module. Some DREs can transmit ballots or vote totals to a central location for the reporting of unofficial results. DREs may be used in precincts on Election Day or in vote centers or during early voting.

Early in their existence, DREs were attractive to some election administrators because they provided a modern, reliable upgrade from mechanical lever machines. DREs seemed convenient to use, because they provided instant tabulation at the close of the polls, and because they eliminated the need to preprint the correct number of paper ballots for all the voters in each precinct.

HAVA directed jurisdictions responsible for federal elections to provide at least one accessible voting system at each polling place. DREs were widely embraced as a solution to the challenge of making voting accessible to the disabled, even in many jurisdictions that adopted optical scan balloting for nondisabled voters.

Although DREs successfully addressed several concerns, they also introduced new challenges. Critics pointed out cybersecurity risks inherent in relying entirely on computers—thereby eliminating a voter-inspected paper artifact that could be manually counted.74 DREs also introduced new usability problems associated with how ballots are displayed on a screen, how users navigate within and across screens, and how voter selections are made. They also introduced new technical challenges; touchscreen miscalibration, for example, can cause a voter’s intended vote for one candidate to be misinterpreted as a vote for another candidate.

The purchase of DREs may require a high initial investment. DREs require software updates and the ongoing payments for technical support costs. Furthermore, DREs introduced new complexities to the vote casting process and are subject to technological obsolescence.

Voting machines that create voter-verifiable paper audit trails (VVPATs) have been introduced to address some of these concerns. A VVPAT is a printout that provides a physical record of a voter’s selections. VVPATs are preserved as a physical record of a cast ballot. While VVPATs provide a physical record of a cast ballot, it is possible that the information stored in a computer’s memory does not reflect what is printed on the VVPAT.

___________________

74 See, e.g., Jones, Douglas W. and Barbara Simons, Broken Ballots: Will Your Votes Count? (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012) and Verified Voting Foundation, “The Resolution on Electronic Voting,” available at: https://www.verifiedvotingfoundation.org/projects/electronic-voting-resolution/.

Voters may inspect a VVPAT to see whether it reflects their intended selections before their votes are recorded in computer memory. If voters do not verify that the information on their VVPAT is accurate, inaccuracies may be recorded. Those with vision or other impairments or limitations may not, however, be able to perform this inspection. Furthermore, it may be difficult to track patterns of VVPAT errors that would indicate fraud. Finally, a combined approach that uses DREs and printers introduces complexity and adds new points of potential failure at the polling place.

Jurisdictions typically transmit ballots to those wishing to cast ballots via mail. Ballots may sometimes be retrieved from an elections website for printing and completion by remote voters. Some jurisdictions may also provide remote voters with software to prepare their ballots. While this software avoids problems associated with manual use of paper ballots such as undervotes and overvotes and spoiled ballots (as voters get immediate feedback before completing their ballots), it introduces additional security risks. Completed ballots are returned via mail, at designated collection points, or, in certain instances, by fax or via the Internet.

Well designed, voter-marked paper ballots are the standard for usability for voters without disabilities. Research on VVPATs has shown that they are not usable/reliable for verifying that the ballot of record accurately reflects the voter’s intent, but there is limited research on the usability of BMDs for this purpose. BMDs moreover, may produce either a full ballot, a summary ballot, or a “selections-only” ballot. Unless a voter takes notes while voting, BMDs that print only selections with abbreviated names/descriptions of the contests are virtually unusable for verifying voter intent.75

Human beings must, however, interact not only with ballots, but also with all components of election systems. A usability failure of any particular component of an election system can be as detrimental as a failure of usability in the ballot. A voting system must be usable in a way that allows a voter to verify that the ballot of record correctly reflects his or her intent. Vote tabulation systems must be usable in a way that facilitates the correct tallying and tabulation of votes. Auditing technology must be useable in a way that enables efficient recounting.

Findings

Not all voting systems have the capacity for the independent auditing of the results of vote casting. Electronic voting systems that do not produce

___________________

75 By hand marking a paper ballot, a voter is, in essence, attending to the marks made on his or her ballot. A BMD-produced ballot need not be reviewed at all by the voter. Furthermore, it may be difficult to review a long or complex BMD-produced ballot. This has prompted calls for hand-marked (as opposed to BMD-produced) paper ballots whenever possible.

a human-readable paper ballot of record raise security and verifiability concerns.

The software for casting and tabulating votes is not uniformly independent in voting systems.

Voting technology raises a particular set of issues for the disabled community.

Additional research on ballots produced by BMDs will be necessary to understand the effectiveness of such ballots.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- 4.10 States and local jurisdictions should have policies in place for routine replacement of election systems.

- 4.11 Elections should be conducted with human-readable paper ballots. These may be marked by hand or by machine (using a ballot-marking device); they may be counted by hand or by machine (using an optical scanner).76 Recounts and audits should be conducted by human inspection of the human-readable portion of the paper ballots. Voting machines that do not provide the capacity for independent auditing (e.g., machines that do not produce a voter-verifiable paper audit trail) should be removed from service as soon as possible.

- 4.12 Every effort should be made to use human-readable paper ballots in the 2018 federal election. All local, state, and federal elections should be conducted using human-readable paper ballots by the 2020 presidential election.

- 4.13 Computers and software used to prepare ballots (i.e., ballot-marking devices) should be separate from computers and software used to count and tabulate ballots (scanners). Voters should have an opportunity to review and confirm their selections before depositing the ballot for tabulation.

VOTING SYSTEM CERTIFICATION

Overview and Analysis

Under HAVA, the EAC became responsible for developing and administering a voluntary system for federal certification of voting systems.77 These

___________________

76 A modern form of optical scanner, a digital scanner, captures, interprets, and stores a high-resolution image of the voter’s ballot at a resolution of 300 dots per inch (DPI) or higher.

77 U.S. Election Assistance Commission, “Testing & Certification Program Manual, Version 2.0,” available at: https://www.eac.gov/assets/1/6/Cert_Manual_7_8_15_FINAL.pdf.

guidelines, known as the Voluntary Voting System Guidelines (VVSG), specify certain functional, accessibility, and security requirements for voting systems.

The EAC has two responsibilities pertinent to certification. First, with the technical assistance of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), the EAC oversees the development of the VVSG, which establishes the standards against which new voting systems are tested. Second, the EAC certifies independent voting system testing laboratories (VSTLs), which conduct the testing of new voting systems developed by commercial vendors.

States are ultimately responsible for determining the process by which voting systems will be certified in their states. Thirty-eight states and the District of Columbia rely on the federal testing and certification program, at least to some extent.78 This can range from requiring that systems be tested to federal standards to requiring that systems be tested in federally approved laboratories. The remaining states do not require federal testing or certification per se, but in most cases rely on the federal certification program to guide their own state certification regimes. HAVA envisioned that the states might also perform testing of the accuracy, usability, and durability of the systems that they proposed to put into service.

The federal certification process begins only once a manufacturer has registered with the EAC Voting System Testing and Certification Program and has submitted a system for certification.79 The process of certification can take up to 2 years.80 Even then, a state certification process frequently follows after federal certification has been received. Following certification, other procedures, such as acceptance testing, logic and accuracy testing, and special purpose tests may follow. All told, the period between the develop-

___________________

78 See National Conference of State Legislatures, “Voting System Standards, Testing, and Certification,” available at: http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/votingsystem-standards-testing-and-certification.aspx.

79 See “Testing & Certification Program Manual, Version 2.0.” Systems are usually “submitted when (1) they are new to the marketplace, (2) they have never before received an EAC certification, (3) they are modified, or (4) the Manufacturer wishes to test a previously certified system to a different (newer) standard.” See p. 19.

80 Perez, Eddie, Hart InterCivic and Coutts, McDermot, Unisys Voting Solutions, presentations to the committee, December 8, 2017, Denver, CO. See also University of Pennsylvania, Wharton Public Policy Initiative, “The Business of Voting: Market Structure and Innovation in the Election Technology Industry,” 2016, p. 38, available at: https://publicpolicy.wharton.upenn.edu/live/files/270-the-business-of-voting.

ment of a new voting systems and its actual use in an election can last years and cost vendors millions of dollars.81

Current security standards certify equipment but not associated procedures and procedural requirements (e.g., auditing). This fact contributes to deficiencies in current standards.

Newly revised voluntary voting system guidelines, called VVSG 2.0, await final approval from the EAC. The new guidelines provide a more modular set of specifications and requirements against which voting systems can be tested to determine whether the systems provide basic functional, accessibility, and security capabilities required of these systems. This change is intended to foster the deployment of accurate and secure voting systems while also enabling system innovation that would allow the deployment of system upgrades in a timely fashion, facilitate interoperability of election systems, permit the transparent assessment of the performance of election systems, and provide a set of testable requirements that are easy to use and understand.82 The approach of VVSG 2.0 focuses more on functional requirements than on the prescriptive specifics of the past. The draft guidelines require software independence for all voting systems in order to allow the correct outcome of an election to be determined even if the software does not perform as intended.83,84

Findings

Vendors and election administrators have expressed frustration with the certification process as presently implemented.

Costs and delays in the certification process may limit vendor innovation and increase system costs.

The requirements of the certification system can create barriers to

___________________

81 The software used in voting systems is also subject to certification. This has important implications for system security. If the most recent version of particular software has not been certified, states may be forced to use an earlier software version with documented vulnerabilities.

82 U.S. Election Assistance Commission, “VVSG Version 2.0: Scope and Structure,” available at: https://www.eac.gov/assets/1/6/VVSGv_2_0_Scope-Structure(DRAFTv_8).pdf.

83 “A voting system is software independent if an (undetected) change or error in its software cannot cause an undetectable change or error in an election outcome.” See Rivest, Ronald L., “On the Notion of ‘Software Independence’ in Voting Systems,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A, October 28, 2008, DOI: 10.1098/rsta.2008.0149. Dr. Rivest is a member of the committee that authored the current report.

An auditable voting system is software independent.

84 The auditing of election results can reduce the need for certification and simultaneously provide better evidence that outcomes are correct. See, e.g., Stark, Philip B. and David A. Wagner, “Evidence-Based Elections,” IEEE Security and Privacy, 2012, Vol. 10, DOI 10.1109/MSP.2012.62.

incremental improvements to systems that reflect improved manufacturing processes or software upgrades. This contributes to the process that has created a population of voting systems that have become obsolete (and therefore harder to secure) when compared even to the technology one encounters in today’s typical office environment.

New approaches to the standards-setting and certification process (i.e., VVSG 2.0) have the potential to mitigate deficiencies in the current system.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- 4.14 If the principles and guidelines of the final Voluntary Voting System Guidelines are consistent with those proposed in September 2017, they should be adopted by the U.S. Election Assistance Commission.

-

4.15 Congress should:

- authorize and fund the U.S. Election Assistance Commission to develop voluntary certification standards for voter registration databases, electronic pollbooks, chain-of-custody procedures, and auditing; and

- provide the funding necessary to sustain the U.S. Election Assistance Commission’s Voluntary Voting System Guidelines standard-setting process and certification program.

- 4.16 The U.S. Election Assistance Commission and the National Institute of Standards and Technology should continue the process of refining and improving the Voluntary Voting System Guidelines to reflect changes in how elections are administered, to respond to new challenges to election systems (e.g., cyberattacks), and to take advantage of opportunities as new technologies become available.

- 4.17 Strong cybersecurity standards should be incorporated into the standards-setting and certification processes at the federal and state levels.