2

Keynote Presentations

As a basis for the workshop’s discussions, two keynote speakers provided an overview of the history and current status of Black men in medicine and the consequences of this problem on the health care workforce and on health outcomes. Louis Sullivan, M.D., provided a historical perspective, reviewing key policies and practices that contributed to the present shortage of Black men in medicine, and described the adverse consequences on health outcomes and health disparities. Darrell G. Kirch, M.D., provided a broader health care context for the issue, describing what he identified as four serious challenges in health care that, to address, require inclusion and, moreover, solving the problem of the shortage of Black men in medicine. Following the presentations, George C. Hill, Ph.D.,1 moderated a brief discussion.

___________________

1 Sullivan is chairman and chief executive officer of The Sullivan Alliance to Transform the Health Professions and president emeritus of the Morehouse School of Medicine. Kirch is president and chief executive officer of the American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC). Hill is Levi Watkins Jr., M.D. professor emeritus in medical education, distinguished professor emeritus in the Department of Pathology, Microbiology, and Immunology, and past vice chancellor for equity, diversity and inclusion and chief diversity officer at Vanderbilt University.

OPENING KEYNOTE

Louis Sullivan, M.D. Chairman and Chief Executive Officer The Sullivan Alliance to Transform the Health Professions President Emeritus Morehouse School of Medicine

Sullivan began by describing how a history of slavery, segregation, discrimination, and bias (both conscious and unconscious) resulted in “less opportunity for Blacks and greater poverty in America’s Black population.” He then described the influence of Abraham Flexner’s 1910 report Medical Education in the United States and Canada,2 which recommended the closure of certain medical schools owing to the inadequate faculty, weak curriculum, and low standards. The report resulted in the closure of many medical schools by 1925, including five of the seven predominantly Black medical schools, leaving Howard University College of Medicine and Meharry Medical College as the only predominantly Black medical schools in the first half of the 20th century.

Sullivan continued by discussing the convergence of an expansion of medical education and the Civil Rights movement in the latter half of the 20th century, which resulted in increasing opportunity for Black men in medicine. Sullivan identified several key contributions to this convergence. First, the Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 resulted in the integration of medical schools. Second, two predominantly Black medical schools, the Morehouse School of Medicine and the Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science, were established. Third, in 1986, the AAMC launched study committees to increase racial and ethnic diversity in medical schools, which issued several recommendations, including broadening and strengthening the educational pipeline.

Next, Sullivan elaborated on the contraction of opportunity for Black men to enter health professions in the United States since the 1980s. He pointed out that a perceived surplus of doctors resulted in the end of the era of expansion for medical schools, and highlighted how decreased state and federal funding for medical education has led to significant increases in tuition for health professional schools, which in turn has contributed to the growing burden of educational debt. He noted that this potential burden may be a financial barrier for racial and ethnic minority students to enter medical school. He added that although the average debt at

___________________

2 For more information, see http://archive.carnegiefoundation.org/pdfs/elibrary/Carnegie_Flexner_Report.pdf (accessed February 20, 2018).

graduation has more than doubled in three decades, the proportion of medical students graduating without debt has increased from 16 percent to 27 percent.3 He commented that this suggests that the proportion of affluent medical students is increasing. Finally, Sullivan described the 2015 AAMC report Altering the Course: Black Males in Medicine,4 which highlighted the failure to increase the number of Black men applying to and entering medical school. Sullivan remarked that, although the number of Black medical students increased overall between 1978 and 2014, gains in representation among Black women were primarily responsible for this overall increase. During the same period, the number of Black male students entering medical schools decreased by 25 percent.

Having provided historical context for the absence of Black men in medicine, Sullivan proceeded to discuss why this absence is problematic—or, why it matters. First, he said, it reflects a lack of opportunity for racial and ethnic minorities to become health professionals, “depriving the nation of the contributions [these individuals] could make to improve their lives, their community, and their country.” Citing a New England Journal of Medicine study by Komaromy and colleagues, Sullivan added that a less diverse health care workforce contributes to the poorer access to health services that racial and ethnic minorities, individuals with low socioeconomic position, and those living in geographically remote areas experience.5 Furthermore, Sullivan noted that less diversity is also likely to result in a less culturally competent health care workforce. He continued to explain that decreased access to health care services and receipt of lower quality health care in turn contribute to the poorer health status of African Americans. Moreover, he argued that a non-diverse health workforce is a problem for the country as a whole. Sullivan quoted from a 2016 Health Affairs article he authored:

When minority students give up their dream of becoming a doctor or other health professional, they are depriving themselves; depriving future patients who would benefit from having a more ethnically and racially diverse health care workforce; and depriving the nation of the

___________________

3 See Grischkan, J., B. P. George, K. Chaiyachati, A. B. Friedman, E. R. Dorsey, and D. A. Asch. 2017. Distribution of medical education debt by specialty, 2010–2016. JAMA Internal Medicine 177(10):1532–1535. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/2652831 (accessed April 27, 2018).

4 For more information, see https://members.aamc.org/eweb/upload/Altering%20the%20Course%20-%20Black%20Males%20in%20Medicine%20AAMC.pdf (accessed February 20, 2018).

5 For more information, see Komaromy, M., K. Grumbach, M. Drake, K. Vranizan, N. Lurie, D. Keane, and A. B. Bindman. 1996. The role of Black and Hispanic physicians in providing health care for underserved populations. New England Journal of Medicine 334:1305–1310. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJM199605163342006 (accessed May 3, 2018).

contributions they could make to improving their lives, their community, and the country. (p. 1534)6

Sullivan closed his talk by challenging his audience:

All of us are challenged to find better answers, better approaches to these challenges, and to find more effective solutions to increase diversity in the health professions. . . . It is up to you, and to me, to provide encouragement and leadership and have others join us in this effort. That is a challenge. We must plan, we must educate and engage our colleagues, then forge ahead. The health of our increasingly diverse nation depends upon it. Our commitment of our society to fairness and equal opportunity demands it. It is up to you and me to see that that happens.

THE PERSPECTIVE FROM ACADEMIC MEDICINE

Darrell G. Kirch, M.D. President and Chief Executive Officer Association of American Medical Colleges

Kirch began by reviewing the AAMC’s role in promoting a diverse medical workforce. He recalled the history of the AAMC and its evolution in supporting diversity and inclusion in medicine. Like much of the nation, the AAMC’s past on the issue demonstrates significant change toward progress. For example, in 1950, W. Montague Cobb asked the association’s leadership to make a statement against discrimination and segregation in medical schools. The AAMC Executive Council noted that while it gave sympathetic consideration to the question presented by Dr. Cobb, the AAMC reaffirmed its traditional position that it is not within the scope of this association to take action on matters that are within the jurisdiction of the individual medical school and a matter of internal administration within that school. Kirch went on to describe the evolution of the AAMC since that time to promote diversity and inclusion, which includes establishing an Office of Minority Affairs and, in 1991, launching the 3000 by 2000 project, a national campaign that aimed to enroll 3,000 underrepresented racial and ethnic minority students in medical school by the year 2000.7 Finally, he presented selected statistics about Black men in medicine, updated from the 2015 AAMC report Altering the Course:

___________________

6 To read the Health Affairs article, see https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/abs/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0382 (accessed February 27, 2018).

7 For more information, see http://www.jdentaled.org/content/67/9/1048.long (accessed February 27, 2018).

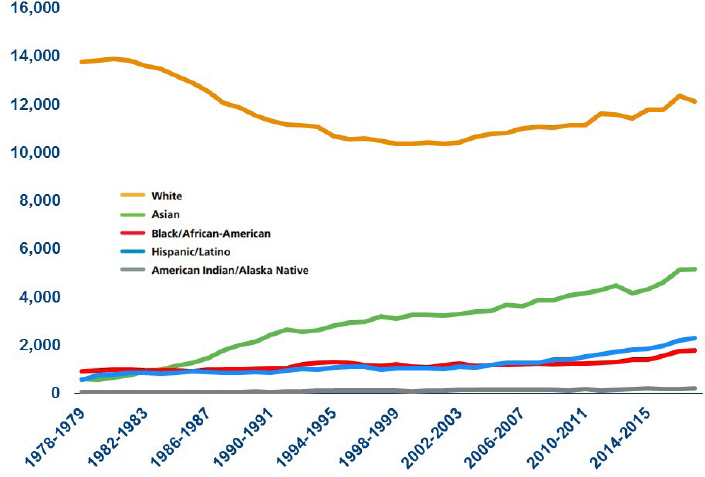

SOURCES: Kirch presentation, November 20, 2017. Data from AAMC, 2017.

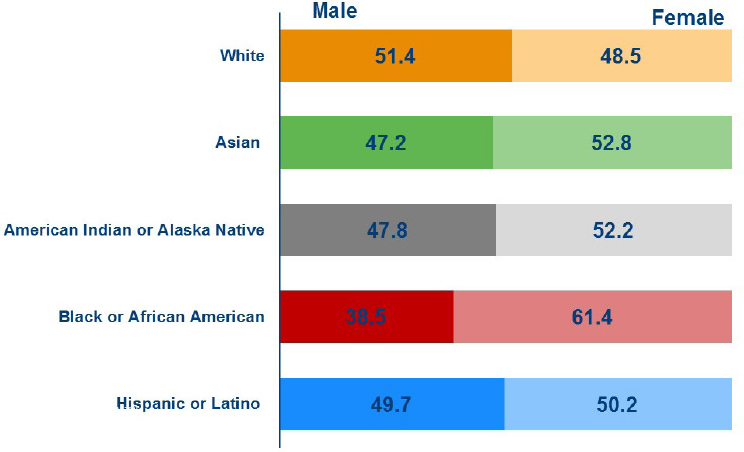

Black Males in Medicine, which Sullivan also cited.8 Adding to Sullivan’s comments on the report in his keynote address, Kirch noted that there has been only a modest increase in the number of Black or African American matriculants to U.S. medical schools since 1978 (see Figure 2-1). With respect to Black men in particular, in 2017, less than 40 percent of those applicants matriculated to medical school. Additionally, although there is near parity of men and women for many racial and ethnic groups, Black or African American matriculants are 61 percent women compared with just 39 percent men (see Figure 2-2).

Kirch then focused his presentation on what he described as four serious challenges for health care. He noted that inclusion is key among the solutions to these challenges, including solving the problem of low participation of Black men in medicine. First, he said, health care reimbursement and delivery are changing rapidly, which requires care models that employ clinician teams. He added that diversity and inclusion

___________________

8 For more information, see https://members.aamc.org/eweb/upload/Altering%20the%20Course%20-%20Black%20Males%20in%20Medicine%20AAMC.pdf (accessed February 20, 2018).

SOURCES: Kirch presentation, November 20, 2017. Data from AAMC, 2017.

are critical to effective teamwork, because, “A team will always solve a problem much better than an individual, and a diverse team will solve a problem much better, much faster than a homogeneous team.” Kirch identified clinician burnout and resilience as the second major challenge, and remarked, “Inclusive work environments . . . help foster resilience and well-being and combat burnout.”

He then described the phenomenon of the “minority tax.” As described in a 2017 article by Kali D. Cyrus in the Journal of the American Medical Association, the minority tax is “the additional responsibilities placed on minority faculty to achieve diversity” or “the expectation [that minority faculty] represent [their] otherness across the institution for the good of the community, often at the expense of the individual.”9 Kirch suggested that the minority tax, in addition to all other causal factors, may contribute to burnout among racial and ethnic minority learners, faculty, and staff. The third challenge Kirch identified was leadership—in particular, the need for a more diverse pool of leaders and for a different

___________________

9 For more information on the minority tax, see https://bmcmededuc.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12909-015-0290-9 (accessed February 21, 2018) and https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2625322 (accessed February 21, 2018).

kind of leader. He described a shift from an outdated model of leaders as “Moses,” in which the leader is a “genius coming down from the mountaintop,” to a leader as a “multiplier . . . who can most effectively activate the genius of all those around him or her.”10 He elaborated that the new leadership model requires the ability to change culture.

The final challenge Kirch identified was the need to achieve a truly holistic selection process for admission into medical school. This requires a shift from traditional criteria such as test scores and grades to different competencies, including academic readiness (i.e., traditional competences in scientific knowledge and quantitative reasoning), diversity, and “preprofessional readiness.” The latter encompasses skills and attributes the AAMC collectively refers to as “15 Core Competencies for Entering Medical Students,” including cultural competence, critical thinking, resilience and adaptability, social skills, teamwork and communications skills, ethical responsibility, and a capacity for improvement.

Kirch closed his presentation with a reminder that the goal of promoting a diverse health care workforce is to improve health equity. Furthermore, he asserted that beyond health, “We need to counter the deep and in some ways growing divisions and injustices that exist in our country and our health system.” He elaborated that academic health centers can serve as a place to bring communities together and “accomplish social repair.”

DISCUSSION

Cedric M. Bright, M.D., FACP,11 asked about the role of scholarship in financing medical education, especially in light of the fact that, as Sullivan mentioned, affluent students comprise an increasingly greater share of medical students. Sullivan remarked that the idea that medical students will become high-earning physicians who can quickly repay their loans with future earnings no longer holds true for many students, and declared the need to counter this assumption. In so doing, he suggested a reframing of the issue of medical education financing as a social problem rather than an individual problem. He said, “We as a society need physicians and other health professionals in the same way we need engineers and lawyers. I see this as an investment in our society.” Kirch suggested a need to reframe how schools think about scholarship, citing “Is There Merit

___________________

10 For more information on multipliers, see Wiseman, L. 2010. Multipliers: How the best leaders make everyone smarter. New York: HarperCollins.

11 Bright is associate dean for inclusive excellence, director of the Office of Special Programs, and associate professor of medicine at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine.

in Merit Aid?” a New England Journal of Medicine article.12 In summarizing the author’s points, he commented, “Schools pursuing scholarships oriented towards academic merit often favor the fairly affluent, which may be subverting our desire to bring in a broader socioeconomic and diverse class.” In closing, Sullivan put forward the need to increase public awareness, advocate for policy issues beyond health and medicine, restore trust in civic institutions, cultivate leadership that collaborates and works together, and rally public support around medical education financing. He said,

What we need to do is develop a community of leaders, both in the public sector and the private sector, to educate the public about this. What we need is public support. . . . It’s not something that an individual can do. We need to have teams of people doing it, but if we are the core, if that is to happen, we’re the ones that have to make it happen.

___________________

12 See http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp1713146 (accessed February 27, 2018).